Introduction

While Japan, parts of Europe and many low- and middleincome countries face concerns about physician shortages, [1-3] the physician workforce has been stable or increasing in other regions such as North America and the United Kingdom [4-7]. Among regions of growth and stability, the momentum of increasing physician supply has largely been driven by the sizable and growing number of physicians who have remained in or re-entered active practice beyond the traditional timing and retirement age of 65 [8,9]. Across OECD countries, nearly onethird of all practicing doctors were on average over 55 years of age (OECD, 2015). In Japan, the percentage of physicians 60 years and older are expected to increase from 20% in 2010 to 36% in 2035, suggesting that if remained unchanged current strategies may insufficiently address future demand for healthcare [10,11].

Along with these demographic shifts are rising concerns that an older physician workforce will be faced with increasing cognitive impairment and associated dementia, as well as, physician burnout and deterioration of physical health potentially producing increased medical errors which put patients and quality of care at risk [12]. Physician retirement can also have a potentially negative impact on patient care as discontinuities in patient care can have implications for patient safety [13] and be particularly difficult for older patients who may be experiencing multiple losses [14].

The abolition of mandatory retirement in the US has encouraged many physicians to extend their medical careers, while in Japan legislative exemptions to the physician profession have supported physicians in accumulating many decades of experience over the course of their working lives generating greater unpredictability of later career transitions [15,16]. Physician retirement planning can create challenges when retirement or death inevitably occurs, because hospitals and medical institutions often find it difficult to replace experienced, older physicians and to facilitate knowledge transfer [17]. The career progression of a growing pool of younger physicians waiting in the wings for professional opportunities can also be impeded without individual physician and institutional hospital succession plans in place [18,19].

Prior research suggests that retirement can be a difficult transition particularly when individuals are unprepared or have a strong sense of wanting to delay their exit because of the value attached to their work [20]. On the other hand, early retirement may be forestalled and retirement transitions better planned in cases where hospital enterprises have developed continuing skills and faculty development programs for staff. Knowledge of when a physician plans to retire and how they can transition out of practice can aid successful succession planning and knowledge transfer. There is a general lack of consensus about the traditional at age of retirement for physicians and indications that there is a variation by region, specialization and institution [21]. Research highlights a need to develop recommendations aimed specifically at how physicians can transition out of their practice and into retirement [22-27].

To our knowledge, no previous studies inform strategies for physician succession planning with a focus on the differences in early, on time and delayed retirement timing. This systematic review explored four key questions: 1) When do physicians retire? 2) Why do some physicians retire early? 3) Why do some physicians delay their retirement? 4) What are some strategies that facilitate physician retention and/or retirement planning?

Methods

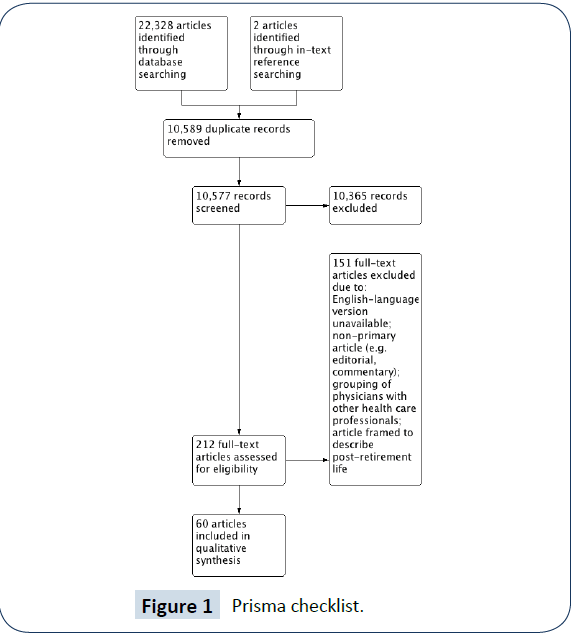

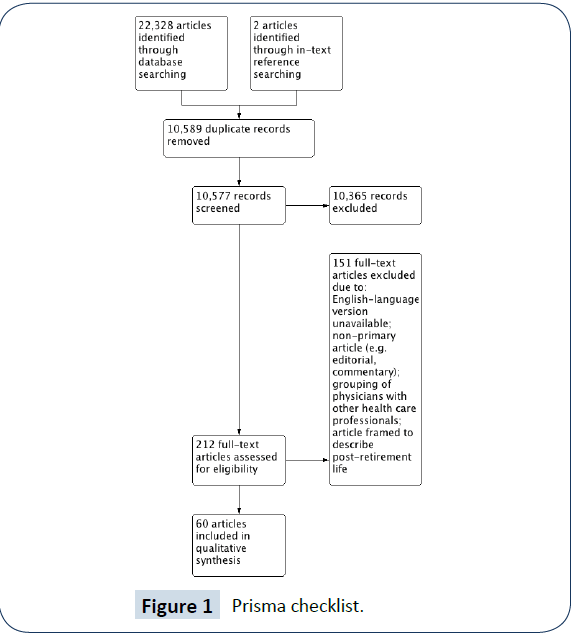

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in the production and reporting of this systematic review [28]. Please see Figure 1 for the PRISMA checklist. Published articles were comprehensively searched using Medline, Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, Ageline, Embase, Health ASSA, and Psychinfo databases up to and including June 2015. Each author participated in the identification and final selection of studies. Thematic analysis was used to identify and stratify concepts related to physician retirement into themes and subthemes [29]. Thematic analysis is an inductive qualitative data analysis process in which data are prepared, then organized using open coding to create categories and themes to build a conceptual understanding of a particular phenomenon and analyze the meaning of data within their particular context [30]. To enhance rigour and replicability of our protocols, we included an audit trail to record completed tasks and track key decisions made with regard to the selection of articles.

Inclusion Criteria

Our inclusion criteria included published primary peer-reviewed journal articles with quantitative and/or qualitative analyses of physicians’ plans for, and opinions about retirement. Nonprimary research studies (editorials and commentaries) and articles grouping physicians with other healthcare professionals were excluded (Figure 1). After discussion, the authors chose to constrain the search strategy to English-language articles, with no limitations on publication date up to June 2015. Our search strategy included the keywords ‘physician’ and ‘retire’ with all appropriate synonyms. We supplemented our search by manually reviewing the reference lists of eligible studies and relevant review articles.

Figure 1: Prisma checklist.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The following information was extracted from qualifying studies: (i) geographic information, study design, data collection methodology, response rate, physician specialty; (ii) expected and actual retirement age; (iii) descriptive statistics related to demographic characteristics of the sample; and (iv) findings related to reasons for retiring, reasons for delaying retirement and obstacles to continued practice. Three reviewers (ADH, AB, and NW) worked in pairwise rotation to independently review the articles for methodological quality. The corresponding author (MPS) resolved any disagreements that could not be settled by consensus. We used the seven-item, Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale to assess the risk of bias for 51 studies using quantitative survey methods according to three domains: sample selection, comparability and ascertainment of outcome [31]. The adapted Critical Appraisal of a Qualitative Study Tool from the Center for Evidence-Based Management was used to assess 9 studies that used qualitative methods [32]. Both tools have previously demonstrated reliability and validity when examining the views of healthcare professionals [33-35].

Results

Study Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 60 studies included in the review. Publication dates ranged from 1978 to 2015 [31]. Studies were based in the United States, with others from Australia, Canada, Finland, Israel, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and one with an international perspective across 20 countries of high, medium and low-income economies. A variety of practicing and retired physicians were sampled with specializations ranging from general and multidisciplinary physicians to anesthesiologists, dentists, general and specialist surgeons, obstetrician-gynecologists, otolaryngologists, ophthalmologists, pediatricians, psychologists, radiologists, and urologists.

| Study |

Location |

Study Method (Source, if not self-administered) |

Sample size (Response rate) |

Participants (Average Age and/or Age Range) |

| Anderson [45] |

United States |

Survey (administered by the American Medical Colleges and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) |

< Age 50, 2000 (40.3%) > Age 50, 2100 (57.3%) |

Obstetrician-Gynaecologists (average age <50 was 44 years, average age >50 was 65 years) |

| Austrom[23] |

United States |

Survey (modified version of American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons survey) |

1834 (43%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians and spouses (average age 75 years) |

| Baker [46] |

United States |

Survey |

500 (46%) |

Psychiatric physicians (age 50 to 69 years) |

| Baker [65] |

United States |

Survey |

125 (53%) |

Black Psychiatrists (age 31 to 74 years) |

| Baker, Hishinuma[23] |

United States |

Survey |

AMA: 187 (58%); NMA: 85 (65%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians. AMA members (age 50 years or older), NMA members (age 30 years or older) |

| Batchelor[47] |

United States |

Survey/Interviews |

20 (80%) |

Senior women physicians (age 59 to 95 years) |

| Bieliauskas[48] |

United States |

Computerized cognitive test/Survey |

359 (82%) |

Surgeons (age 45 or older, average age 61.4 years) |

| Brett [38] |

Australia |

Survey |

281 (59%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 45 to 65, average age 52.4 years) |

| Burke [52] |

United Kingdom |

Administrative data, Department of Health and Insurance industry (The Dentists' Provident Society) |

393(N/A) |

Retired Dentists (N/A) |

| Chambers [73] |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

348 (72%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age 55 years) |

| Davidson (45) |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

2398 (78%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age mid-40s) |

| Davidson (76) |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

1460 (85%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age 48 years) |

| Deitch[56] |

United States |

Survey (ACR Committee on Manpower) |

2804 (69%) |

Radiologists, Radio oncologists, and Nuclear Medicine Specialists (average age in years <35 (11%), 35 and 44 (37%), 45 and 54 (32%) and 55 or older (20%). |

| De Santo |

Algeria, Australia, Brazil, Egypt,

France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Malta, Libya,

Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia,

Switzerland, The Netherlands, Tunisia, Turkey, UK and USA |

Survey |

113 (89.1%) |

Active professors and emeritus/retired professors from 99 departments of medicine/universities worldwide (NA) |

| Dodds[50] |

United States |

Survey |

96/116 (82%) |

Academic Chairs of Ophthalmology departments (age range <50 to > 70, average age 58 years) |

| Donner |

United States |

Review of data based on Survey (ACR Commission on Human Resources, 2012 and 2013) |

N/A |

Radiologists |

| Draper [24] |

Australia and New Zealand |

Survey |

281 (60%) |

Psychiatrists (age 55-87 and average age 65.5 years) |

| Draper [24] |

Australia, New Zealand |

Survey (Respondents were Fellows of the Royal

Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists resident in Australia or New Zealand) |

57.90% |

Psychiatrists (age 40 years and older) |

| Eagles [74] |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

180(50%) |

Consultant Psychologists (N/A) |

| Farley [43] |

United States |

Survey (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in cooperation with the Association of American Medical Colleges Center for Workforce Studies) |

3001 (33.5%) |

Orthopaedic Surgeons (age 50 years and older) |

| Fletcher, Schofield[59] |

Australia |

Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Medical Labour Force

Survey from 1995 to 2003 |

N/A |

Psychiatrists (age 50 years and over) |

| Florence |

United States |

Survey |

785(22%) |

Transplant Surgeons (average age 48.7 years) |

| French [62] |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

2923(61%) |

Consultants and specialists (average age 47 years) |

| French [62] |

United Kingdom |

Survey/interviews/focus groups |

924 (50%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age 43 years) |

| Gee |

United States |

Telephone interview (Gallup Poll) |

451 (89%) |

Urologists (age in years <36 (9%), 37 to 45 (29%), 46 to 54 (30%), 55 to 64 (25%), <65 (7%). |

| Goldberg [51] |

United States |

Survey of American College of Emergency Physicians members (two separate mailings in

the fall of 2006 and winter of 2007) |

1000 (80%) |

American College of Emergency Physicians members over the

age of 55 years (average age 57 years) |

| Grauer, Campbell [63] |

Canada |

Survey |

58 (53.7%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age 71.2 years) |

| Greenfield, Proctor |

United States |

Survey |

659 (75%) |

Surgeons (age in years <50 (7%), 50-60 (29%), 60-70 (35%), >70 (28%) |

| Gregory, Menser |

United States |

Longitudinal (three wave) online survey |

97, 91, 56 (65.5%, 54.9%, 58.4%) |

Primary/Ambulatory care physicians (N/A) |

| Grondin |

Canada |

Survey |

97 (71%) |

Thoracic Surgeons (average age 47.7 years) |

| Hall[15] |

United States and Canada |

Survey |

1444 APS members (35%); 148 Pediatric Department Chairs (40%) |

Senior Pediatricians and Pediatric department Chairs (age 39 to 94, average age 65 years) |

| Heponiemi[36] |

Finland |

Survey (Finnish Health Care Professional Study) |

1393 (27.9%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 45 to 65 years) |

| Hill [52] |

United Kingdom |

Semi-structured interviews/Survey |

23 (N/A) |

Dentists (NA) |

| Jacobson, Eran[39] |

Israel |

Interview |

317 (89.5%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 50 years or older) |

| Jonasson, Kwakwa[44] |

United States |

Survey |

373 (84%) |

General Surgeons (NA) |

| Kendell, Pearce |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

173(82%) |

Consultant psychiatrists (NA) |

| Landon [57] |

United States |

Data for this study are from the first 2 rounds of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Physician Survey |

39185(63%) |

Primary care and specialist physicians initially spending at least 20 hours per week in direct patient care activities were studied (average age 47.5 years for practicing and 63.0 years for retired physicians) |

| Lee |

United States |

Telephone Interview/Survey |

33 (75%) |

Multidisciplinary rural physicians (age 60 years or older) |

| Lee |

United States |

Survey |

995 (N/A) |

Surgeons (age in years <35 (13.37%), 35–44 (12.96%), 45–54 (18.69%), 55–65 (31.06%), >65 (23.92%)) |

| Luce |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

518 (72.5%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 45 years or older) |

| Moriarty |

United States |

Survey sent to all members of the American College of Radiology (ACR), the Association of University Radiologists

(AUR), and the Society of Chairs of Academic Radiology Departments

(SCARD) |

~37900 (11%) |

Practicing radiologists (NA) |

| McGuirt, McGuirt (2002) |

United States |

Survey |

438 (31.5%) |

Otolaryngologists (age 40 to 80, average age 63.2 years) |

| Mears [40] |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

835 (59%) |

Consultant psychologists (age 50 years or older) |

| Meghea, Sunshine [64] |

United States |

Survey (American College of Radiology's 2003 Survey of Radiologists |

1676 (63%) |

Radiologists (age 35 to 75 years) |

| Newton [37] |

United Kingdom |

Semi-structured interviews |

21 (N/A) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 44 years or older) |

| Onyura[60] |

Canada |

Secondary analysis of data from a larger study on

issues of late-career planning among

academic physicians and semi-structured interviews |

21 |

Academic physicians

at a Canadian medical school (n=21, average age= 63 years, age range: 46-72 years) |

| Orkin[58] |

United States |

Survey |

8670 (37.2%) |

Anaesthesiologists (age 50-79 years, average age 60.1 years) |

| Peisah[25] |

Australia, Canada, United States |

Semi-structured interviews |

25 (N/A) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (aged 60 or older, average age 67.5 years, age range: 60-88 years) |

| Pit, Hansen [41] |

Australia |

Survey |

92(56%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age 51 years) |

| Quandango[26] |

United States |

Semi-structured interviews |

40 (N/A) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 55 to 72) |

| Rayburn [16] |

United States |

Data is from the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Master file |

N/A |

Obstetrician-gynaecologists |

| Reuben, Silliman[53] |

United States |

Survey |

282 (70%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 65 or older, average age 71 years) |

| Rittenhouse |

United States |

Survey |

967 (N/A) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (< 55 years, 62.8 %, 55–64 years, 27.3%, >65 years, 9.9%) |

| Rowe [66] |

United States |

Survey |

169 (84%) |

Physicians (52-96 years) |

| Shanafelt[55] |

United States |

Survey conducted by The American Society of Clinical Oncology |

2998 (49.7%) |

US oncologists |

| Sibbald |

United Kingdom |

Survey |

1949 (N/A) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age 55 years) |

| Silver [19] |

Canada |

Focus Groups |

16 |

Academic physicians over 50 years

old within the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto |

| Smith |

Canada |

National survey was administered to all Canadian otolaryngologists |

65 (65%) |

Otolaryngologists who were identified to have a clinical practice composed of >50% rhinology (average age: 46 years) |

| Sutinen[27] |

Finland |

Survey |

819 (55%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (age 26 to 63 years) |

| Wakeford[61] |

United Kingdom |

Interview |

250 (79%) |

Multidisciplinary physicians (average age: 61.4 years) |

Table 1: Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 summarizes the quality assessment of the reviewed studies. There were considerable variations in the methodological quality of the 51 studies using a quantitative methodology. The majority of studies scored highly on sample representativeness (75% of studies), justified and satisfactory sample size (90% of studies), appropriate statistical tests (59% of studies), while they primarily collected data by self-reported survey methods (90 % of studies). The majority of studies rated poorly on the ascertainment of exposure as they used non-validated measurement tools (55% of studies), and on comparability, as they did not control for any potential confounders (49% of studies). The majority of qualitative studies reviewed were found to be methodological strong, with credible results that were adjudged to be relevant to practice.

| Studies with Quantitative Methodology |

| |

Selection |

Comparability |

Outcome |

Quality

score |

| |

R Representativeness

of sample |

Sample size |

Non-respondents |

Ascertainment of exposure |

Assessment of outcome |

Statistical test |

|

| Anderson [45] |

A |

A |

B |

C |

A |

C |

A |

6 |

| Austrom[22] |

B |

A |

A |

B |

- |

C |

A |

6 |

| Baker [46] |

A |

A |

A |

C |

- |

C |

B |

4 |

| Baker [65] |

A |

A |

A |

B |

- |

C |

B |

5 |

| Baker, Hishinuma[23] |

B |

A |

B |

B |

A/B |

C |

A |

7 |

| Biellauskas |

B |

B |

C |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

6 |

| Brett [38] |

B |

B |

B |

B |

- |

A |

A |

5 |

| Burke [49] |

C |

A |

C |

B |

- |

C |

B |

3 |

| Chambers [73] |

A |

A |

A |

A |

- |

C |

B |

6 |

| Davidson [76] |

A |

A |

A |

C |

- |

C |

A |

5 |

| Davidson [42] |

A |

A |

C |

B |

A |

C |

A |

6 |

| Deitch[56] |

A |

A |

A |

B |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| De Santo |

A |

A |

B |

B |

- |

C |

B |

4 |

| Dodds[50] |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

9 |

| Donner |

D |

C |

C |

C |

- |

D |

B |

0 |

| Draper [24] |

A |

A |

A |

B |

A |

C |

A |

7 |

| Draper [24] |

A |

A |

B |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Eagles [74] |

A |

A |

B |

B |

A |

C |

B |

5 |

| Farley [43] |

A |

A |

B |

A |

- |

C |

B |

4 |

| Fletcher, Schofield [59] |

A |

A |

C |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Florence |

A |

A |

B |

B |

- |

C |

B |

4 |

| French |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A |

C |

A |

8 |

| Gee |

A |

A |

B |

B |

- |

C |

A |

5 |

| Goldberg [51] |

A |

A |

B |

A |

- |

C |

A |

6 |

| Grauer, Campbell [63] |

D |

B |

C |

B |

- |

C |

B |

2 |

| Greenfield,Proctor |

A |

A |

B |

B |

A |

C |

B |

5 |

| Gregory, Menser |

B |

A |

B |

A |

A |

C |

A |

7 |

| Grondin |

A |

A |

B |

A |

- |

C |

A |

6 |

| Hall [15] |

A |

A |

B |

B |

- |

C |

B |

4 |

| Heponiemi [36] |

A |

A |

B |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Jonasson, Kwakwa [44] |

A |

A |

B |

B |

A |

C |

B |

5 |

| Kendell, Pearce |

A |

A |

B |

C |

- |

C |

B |

3 |

| Landon [57] |

B |

A |

A |

B |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Lee |

A |

A |

A |

B |

- |

C |

B |

5 |

| Lee |

B |

A |

B |

B |

- |

C |

A |

5 |

| Luce [54] |

A |

A |

B |

A |

- |

C |

A |

6 |

| Moriarty |

A |

B |

B |

B |

A/B |

C |

B |

5 |

| McGuirt |

B |

A |

B |

B |

- |

C |

B |

4 |

| Mears [40] |

A |

A |

B |

B |

A |

C |

A |

6 |

| Meghea, Sunshine [64] |

A |

A |

A |

B |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Onyura [60] |

B |

A |

C |

B |

- |

C |

B |

4 |

| Orkin[58] |

A |

A |

B |

B |

A/B |

C |

A |

7 |

| Pit, Hansen [41] |

B |

A |

B |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Rayburn [16] |

A |

A |

B |

B |

- |

B |

B |

5 |

| Reuben, Silliman [53] |

A |

A |

A |

B |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Ritternhouse |

A |

A |

A |

B |

A/B |

B |

A |

9 |

| Rowe [66] |

A |

A |

B |

C |

- |

C |

B |

3 |

| Shanafelt |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

9 |

| Sibbald |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A/B |

A |

A |

9 |

| Smith |

A |

A |

C |

A |

- |

C |

B |

5 |

| Sutinen[27] |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A/B |

C |

A |

8 |

| Studies with qualitative methodology |

|

| |

Batchelor [47] |

French |

Hill [15] |

Jacobson,Eran[39] |

Newton |

Peisah, Gautam, Goldstein [25] |

Quandango |

Silver, Pang, Williams [19] |

Wakeford, Roden, Rothman [61] |

| 1. Does the study address a clearly focused question/issue? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 2. Is the research method (study design) appropriate for answering the research question? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 3. Was the context clearly described? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 4. How was the fieldwork undertaken? Was it described in detail? Are the methods for collecting data clearly described? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

| 5. Could the evidence (fieldwork notes, interview transcripts, recordings, documentary analysis, etc.) be inspected independently by others? |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

| 6. Are the procedures for data analysis reliable and theoretically justified? Are quality control measures used? |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

| 7. Was the analysis repeated by more than one researcher to ensure reliability? |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

| 8. Are the results credible, and if so, are they relevant for practice? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 9. Are the conclusions drawn justified by the results? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

| 10. Are the findings of the study transferable to other settings? |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Table 2: Studies withquantitative and qualitative assessment

Physician Retirement Age

Several studies examined the age that physicians expected to retire, and/or the age they actually retired (Table 3). The most commonly reported average age for actual and expected retirement was between 60 and 69 years, respectively. The majority of physicians’ reported actual retirement age was found to be consistent with their expected retirement in all studies where the actual and expected retirement ages were jointly reported.

| |

50-59 years |

60-69 years |

>70 years |

“Never” |

| Expected Retirement Age |

Burke [49]

Eagles [74]

Luce [54]

Fletcher [59]

Mears [40]

Goldberg [51] |

Anderson [45]

Dietch

Dodds [50]

Farley [43]

Florence

Grondin

Mears [40]

French

French

Gee

Pit [41]

Rayburn [16]

Shanafelt

Smith

Wakeford [61] |

Batchelor [47] |

Draper [24] |

| Actual Retirement Age |

Baker [65]

Eagles [74] |

Anderson [45]

Austrom [22]

Batchelor [47]

Farley [43]

Fletcher [59]

French

Jonasson [44]

Meghea [64]

Luce [52]

Orkin [58]

Rayburn [16]

Rowe [66]

Wakeford [61] |

Rayburn [16] |

- |

*Note: Average or highest reported ages retirement ages are reported. Studies where the majority of physicians met retirement age expectations are underlined

Table 3: Expected and actual physician retirement age*

Reasons for Retiring Early

Commonly cited reasons for physicians retiring early included low job satisfaction, medicolegal issues, health concerns, and financial troubles. Low job satisfaction involved perceptions of low job control and dissatisfaction with the internal justice system of medicine as a self-regulated profession [27,36,37]. This disillusionment was expressed by a sense of frustration with colleagues [38,39] feeling undervalued, lacking prestige [40,41] and a loss of interest in their work [42,44]. Medicolegal issues often arose from a lack of satisfaction with the regulation of medicine for reasons of unwelcome change, bureaucracy, oppressive management [40,42,43] and issues with physician partners [25,37]. Experiencing poor health, cognitive decline, difficulty sleeping and psychological distress were also factors leading to a physician’s retirement [22,38,41,45-52]. The decision to retire early was also linked to preserving one’s health so they may lead a healthy retirement [38,42]. Financial issues contributing to a physician’s early retirement included: increasing costs of retaining a practice, malpractice costs and other economic pressures, [15,39,43,45,53] insufficient financial remuneration and, pension security [42,50,54,55]. Several studies noted that physicians working in institutions or in countries where the policy landscape changed considerably were more inclined to retire because of perceptions around doctoring regulations and poor work satisfaction as a result of circumstances arising from the delivery of care [19].

Reasons for Delaying Retirement

Reasons that physicians gave for delaying retirement included satisfaction with their career [41,43,45,53,56-58], institutional flexibility, [38] a feeling of responsibility for their patients, [38,45,53,59-61] health and a desire to keep active, [36,50,58,61] financial reasons, [43,50,53,54,55,58,62-64] and a lack of interests outside of medicine.61 Institutional flexibility was a positive driver of a physician’s work satisfaction and their desire to remain in practice as they were provided reasonable access to sabbaticals, flexible working hours and control over their job and career development [38,43,54,76]. Continuing to practice medicine is deeply rooted in a desire to keep active and focus on the social and intellectual elements of continuing to practice [46,50,53]. Several studies also pointed to a link between physicians’ restrictive availability of free time and development of external hobbies, or interests. Still, other studies suggested that continuing in medicine was a better alternative to life in retirement [46,65,42].

Strategies to Facilitate Physician Retention and Retirement Planning

Physicians expressed concerns over their decision to retire due to fears that they may lose their role, identity or purpose, [22,51,60,63] or were uncomfortable with the methods used to enforce their retirement [22]. Retirement concerns also stemmed from personal issues such as a fear of potential changes in the relationship with their spouse following retirement [22], a fear of excessive leisure time and lack of hobbies [63] and inadequate financial preparation for retired life [51,58]. Obstacles to ongoing practice contributed to reasons why participants disliked working, and when they felt strongly enough, these reasons were sufficient to warrant retirement (Table 4). Table 5 summarizes schemes described by studies to enhance physician retention and entice continued practice.

| Subtheme |

Study |

| Workplace frustration: bureaucracy, accreditation, health care reform, alienation by changes to working life, low job control, low organizational justice, poor teamwork and workforce shortages |

Brett [38]; Heponiemi[36]; Hill [52]; Kendell& Pearce; Lee; McGuirt; Mears [40]; Newton [37]; Sutinen[27]; Fletcher, Schofield [59] |

| Workload pressures: patient demands, long hours, demanding on call schedules and sacrifice of family/free time, work-life balance |

Brett [38]; Chambers [73]; French; Mears [40]; Meghea, Sunshine [64]; Newton [37]; Goldberg [51], Sibbald; Draper [24]; Onyura[60];Shanafelt |

| Career dissatisfaction: lost interest in work |

Brett [38]; Chambers [73]; Hill [52]; Luce [54]; Orkin[58]; Ritternhouse; Sibbald; Landon [57] |

| Health: Excessive stress, health and mental health concerns (thoughts of suicide, emotional exhaustion), and spousal health |

Dodds[50]; Hall [15] ; Hill [52]; Luce [54]; Newton [37]; Pit, Hansen [41]; Goldberg [51]; Draper [24] |

| Finances: Pension, economic concerns, costs of continuing to practice, retirement not being written into partner agreements, general guidance |

French; Grondin; Hall [15]; Lee; Orkin[58]; Wakeford[61] |

| Skills and competencies: Worry over competencies amidst technological advancements and new modalities of diagnosis or treatment |

Grauer,Campbell [63]; Hall [15]; Goldberg [51]; Draper [24] |

| Not addressed |

Not applicable in 22 studies |

Table 4: Obstacles to Practice

| Subtheme |

Study |

| Flexible work hours: part-time employment options, gradual reduction, flexible hours or sabbatical, decreased on-call, relief of workload pressure |

Anderson [45]; Brett [38]; Davidson [42]; Eagles [74]; French; French; Hall [15]; Jacobsen, Eran; Newton [37]; Goldberg [51] |

| Minimal work barriers: less bureaucracy, increased staff, improved working conditions, support to maintain/update competencies, more time with patients |

Brett [38]; Davidson [42]; Eagles [74]; Kendell, Pearce |

Work satisfaction: professional/clinical freedom, attend conferences and rounds,

office space, chances to develop or change content of their work (i.e. teaching opportunities) |

Brett [38]; Chambers [73]; Eagles [74]; Farley [43]; Hall [15]; Landon [57] |

| Health: Continuing good or better than expected health at expected retirement age, strategies to reduce work-related stress |

Brett [38]; Davidson [42]; Draper [24]; Luce [54]; Pit & Hansen [41] |

| Finances: Protected pensions, being highly paid, financial necessity |

Brett [38]; Davidson [42]; Eagles [74]; French; Hall [15]; |

| Not addressed |

Not applicable in 41 studies |

Table 5: Retention Schemes

Discussion

The timing of physician retirement is particularly salient for patient care continuity and transitions of care in hospital enterprises where mentors of the younger hospitalist workforce may be scarce [17]. As for the age at which most physicians retired, we found that the majority retired later than the traditional retirement age of [65]. The graceful and timely exit of the well-established physician can be facilitated by health care organizations. Physician perceptions of ageism and being “pushed out” [37] by other partners are unlikely to promote successful retirement transitions and may have undesirable consequences such as litigation. On the opposite end of the spectrum, resisting the incorporation of retirement schedules and procedures into practice plans has also posed a barrier to retirement and succession planning [61]. Given that an important component of successful retirement planning concerns the creation of meaningful activity after retirement, [16] health care organizations should consider developing retirement resource toolkits, education sessions, and guidance around financial planning for physicians throughout their careers and creating post-retirement opportunities.

A principle question of this research aimed to characterize the literature examining factors underlying physicians early retirement. For instance, while early retirement among some physicians’ has been prompted by concerns over competency amid technological advancement [44,66]and the introduction of electronic medical records [55], these are one type of work barrier that can be addressed by organizations through the provision of enhanced training. This study found that a physician’s decision to retire early is often strongly influenced by negative dimensions of work satisfaction. Furthermore, most of the studies suggested that a supportive and highly satisfying work environment facilitated physician retention. To explain these responses, work satisfaction theory proposes an association between work satisfaction and career opportunities, resource adequacy, intrinsic (value or reward), convenience, financial incentives, and relations with co-workers as reasons why work-related frustrations can lead to early retirement [67].

While much of the prior research has focused on addressing the potential impact of early retirement on workforce planning, a subset was concerned with the problems that can arise when physicians remain in practice longer than is safe or reasonable for the proper functioning of the medical organization. The aspects of Work Satisfaction Theory most pertinent to delayed retirement of physicians are the intrinsic characteristics associated with the work itself, the convenience, referring to manageable levels of work demands, and a separate dimension—resource adequacy, which evaluates whether resources are available for physicians to do their job. Through this body of literature we identified factors associated with physicians who delayed timing of their retirement. For instance, health organizations that offered flexibility and a gradual reduction in work hours for supported physicians approaching retirement to remain in practice. Longer employment and more flexible options for retirement are two approaches currently used in Japan to address labour shortages [68].

Another aim of this research was to identify and synthesize the literature on strategies used by health care organizations interested in facilitating physician retention and successful retirement planning. Findings from this study point to a number of factors that support physician retention such as the incorporation of flexible work hours, improving work satisfaction and reducing work barriers. Successful retirement planning was found to be related to being prepared for the financial demands, physical changes, and psychosocial dynamics associated with aging and leaving the workforce [69-71]. This can result in the dual effect of better staff retention and improved work satisfaction.45 Likewise, a reduction of hours and a shift toward preferred duties such as teaching and mentorship may help to facilitate knowledge transfer to younger professionals. Health organizations may be able address work barriers through modifying workflow by adding more staff, and offering training or support.

The theory of purposeful work behaviour [72] posits that when job characteristics act in concert with an individual’s motivational striving, that psychological meaningfulness may be gleaned from their work. Thus, if physicians are given opportunities to pursue preferred work tasks such as teaching over clinical rounds [73,74] then their experiences of greater meaningfulness in their work will trigger task-specific motivation [72]. This can result in a willingness to continue working in hospital settings while also benefiting the enterprise as a whole.

Health was also shown to be an important factor determining whether physicians chose to remain in the workforce. As such, health care organizations may consider strategies that improve physician health by addressing the personal physical fitness and risk-related habits of physicians. Some potential interventions might include encouraging a culture of taking sick days [75] along with proper mechanisms that allow physicians not to overburden one another when taking sick days. Developing interventions to reduce physician and staff stress would also help enhance physician well-being [41,54].

Preparation for retirement that is tailored to specific life and career stages can make these transitions normative and avoid the complications that arise when physicians stay in their role beyond what is safe from a patient perspective or beyond what is in the best interests of the medical practice plan. Health care organizations can also support successful transitions to retirement [58] through the creation of volunteer roles66 and new connections to the institution or organization such as teaching, mentoring, or peer support [73].

Research on the factors that influence physician retirement timing and planning for retirement is still in its early stages and future exploration is needed to further delineate our preliminary findings. To simplify our analyses, we focused on English-language studies, which may create publication bias by inadvertently excluding the perspectives of physicians from non-English speaking regions while disproportionately weighing studies from North America and the United Kingdom. Furthermore, our analysis is based on a heterogeneous sample of physicians spanning across diverse specializations, with jurisdictional differences in regulations, mandatory retirement legislation, pension systems, and differences in remuneration across health care systems. To improve the generalizability of future studies, future studies should inspect physician perspectives based on specialization, include more information about the health care context in which the physicians practice, and consider following physicians over time to better understand factors that facilitate planning for a transition from practice.

Excessive workload, poor health, low job satisfaction and disillusionment were found to be major reasons a physician may choose to retire. Hospitals and health care organizations ought to consider the impact of a physician’s flexible work hours, gradual reduction in responsibilities, and resources for financial planning when developing strategies that facilitate physician retirement planning. Such strategies should be designed in a way that is both effective and respectful to individuals at later stages in their careers.

Conclusion

By the above study we conclude the systematic review Systematic Review of Physician Retirement Planning through different characteristics like physician retention and retirement planning, physical retirement age, workload, job satisfaction and quality assessment of the reviewed studies. This study says that a physician’s decision for early retirement due to different causes like work force and tension and mental stage of the mind based on the work. To keep health in a state of good condition is by keeping the workload in control and the management of time to overcome the pressure.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the University of Toronto Department of Medicine and from the Mitacs-Accelerate Program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

18820

References

- Deo M (2013) Doctor population ratio for India - the reality. Indian J Med Res137:632-635.

- Hoyler M (2014) Shortage of doctors, shortage of data: a review of the global surgery, obstetrics, and anesthesia workforce literature. World J Surg 38:269-280.

- Yuji K, Imoto S, Yamaguchi R, Matsumura T, Murashige N, et al. (2012) Forecasting Japan's physician shortage in 2035 as the first full-fledged aged society. PloS One 7: e50410.

- Evans RG, McGrail KM (2008)Richard III, Barer–Stoddart and the daughter of time.Healthc Policyn3:18-28.

- Kaitelidou D, Mladovsky P, Leone T, Kouli E, Siskou O, et al. (2012) Understanding the oversupply of physicians in Greece: the role of human resources planning, financing policy, and physician power.nInt J Health Serv 42:719-38.

- Pond B, McPake B (2006) The health migration crisis: the role of four organisations for economic cooperation and development countries. The Lancet 367:1448-1455.

- World Bank Group (2016) World Health Organization's Global Health Workforce Statistics, OECD, supplemented by country data.

- Chan BT (2002) From perceived surplus to perceived shortage: what happened to Canada's physician workforce in the 1990s? Canadian Institute for Health Information Ontario, Ottawa.

- Rice B (2003) Retire early? These docs did--and came back.Med Econ 80:43-46.

- Yuji K, Imoto S, Yamaguchi R, Matsumura T, Murashige N, et al. (2012) Forecasting Japan's physician shortage in 2035 as the first full-fledged aged society. PloS one7:e50410.

- Hazzard WR (2004) Capturing the power of academic medicine to enhance health and health care of the elderly in the USA. Geriatrics & Gerontology International4:5-14.

- LoboPrabhu SM, Molinari VA, Hamilton JD, Lomax JW (2009) The aging physician with cognitive impairment: approaches to oversight, prevention, and remediation. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry17:445-454.

- Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T (2003) Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 18:646-651.

- Hamdy RC (2015) Do we need more geriatricians or better trained primary care physicians? Gerontol Geriatr Med pp.1-2.

- Hall JG (2005) The challenge of developing career pathways for senior academic pediatricians. Pediatric Research 57:914-919.

- Rayburn WF, Strunk AL, Petterson SM (2015) Considerations about retirement from clinical practice by obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213:e1-4.

- Kneeland PP, Kneeland C, Wachter RM (2010) Bleeding talent: a lesson from industry on embracing physician workforce challenges. J Hosp Med5:306-310.

- Racine M (2012) Should older family physicians retire? Yes.Can Fam Physician 58:22-24.

- Silver MP, Pang NC, Williams SA (2015) "Why give up something that works so well?": Retirement expectations among academic physicians. Educational Gerontology 41:333-347.

- Roberts LR, Schuh H, Sherzai D, Belliard JC, Montgomery SB, et al. (2015) Exploring experiences and perceptions of aging and cognitive decline across diverse racial and ethnic groups. Gerontol Geriatr Medn1: 1-10.

- Saure PU, Zoabi H (2013)Retirement age across countries: The role of occupations. Tel Aviv: The Pinhas Sapir Centre for Development Tel Aviv University pp54.

- Austrom MG, Perkins AJ, Damush TM, Hendrie HC (2003) Predictors of life satisfaction in retired physicians and spouses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:134-41.

- Baker FM, Hishinuma ES (2002) AMA and NMA members: Retirement planning and definition of a good quality of life. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 35:169-192.

- Draper B, Winfield S, Luscombe G (1997) The older psychiatrist and retirement.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 12:233-239.

- Peisah C, Gautam M, Goldstein MZ (2009) Medical masters: a pilot study of adaptive ageing in physicians.Australas J Ageing 28:134-138.

- Quadagno JS (1978) Career continuity and retirement plans of men and women physicians: the meaning of disorderly careers. Work and Occupations5:55-74.

- Sutinen R, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Forma P (2005) Associations between stress at work and attitudes towards retirement in hospital physicians. Work & Stress 19:177-185.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151:264-269.

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T (2013) Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences 15:398-405.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 62:107-115.

- Wells GA, Shea B, connell OD, Peterson JE, Welch V, et al. (2014) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. The Ottawa Hospital, Research Institute.

- Crombie IK (1996) The pocket guide to critical appraisal: A handbook for health care professionals.nBMJ pp. 63.

- Bunn F, Goodman C, Pinkney E, Drennan VM (2015) Specialist nursing and community support for the carers of people with dementia living at home: an evidence synthesis. Health Soc Care Communityn24: 48-67.

- Reed MC, Wood V, Harrington R, Paterson J (2012) Developing stroke rehabilitation and community services: a meta-synthesis of qualitative literature.Disabil Rehabil 34:553-563.

- Schadewaldt V, McInnes E, Hiller JE, Gardner A (2013) Views and experiences of nurse practitioners and medical practitioners with collaborative practice in primary health care - an integrative review. BMC Family Practice 14:132.

- Heponiemi T, Kouvonen A, Vänskä J, Halila H, Sinervo T, et al. (2008) Health, psychosocial factors and retirement intentions amongFinnish physicians.Occup Med (Lond) 58:406-12.

- Newton J, Luce A, van Zwanenberg T, Firth-Cozens J (2004) Job dissatisfaction and early retirement: a qualitative study of general practitioners in the Northern Deanery. Primary Health Care Research and Development 5:68-76.

- Brett TD, Arnold-Reed DE, Hince DA, Wood IK, Moorhead RG, et al. (2009) Retirement intentions of general practitioners aged 45–65 years. Med J Aust 191:75-77.

- Jacobson D, Eran M (1980) Expectancy theory components and nonâ€ÂÂÂÃÂexpectancy moderators as predictors of physicians' preference for retirement. Journal of Occupational Psychology 53:11-26.

- Mears A, Kendall T, Katona C, Pashley C, Pajak S, et al. (2004) Retirement intentions of older consultant psychiatrists. BJ Psych Bulletin 28:130-132.

- Pit SW, Hansen V (2014) Factors influencing early retirement intentions in Australian rural general practitioners.Occup Med (Lond) 64:297-304.

- Davidson JM, Lambert TW, Parkhouse J, Evans J, Goldacre MJ, et al. (2001) Retirement intentions of doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1974: postal questionnaire survey. J Public Health Medn23:323-328.

- Farley FA, Kramer J, Watkins-Castillo S (2008) Work satisfaction and retirement plans of orthopaedic surgeons 50 years of age and older. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466:231-238.

- Jonasson O, Kwakwa F (1996) Retirement age and the work force in general surgery.Ann Surg 224:574-582.

- Anderson BL, Hale RW, Salsberg E, Schulkin J (2008) Outlook for the future of the obstetrician-gynecologist workforce. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199:88e1-8.

- Baker FM (1993) A survey of retirement planning by Texas psychiatrists.J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol6:14-19.

- Batchelor AJ (1990) Senior women physicians: the question of retirement.N Y State J Med 90:292-294.

- Bieliauskas LA (2008) Cognitive changes and retirement among senior surgeons (CCRASS): results from the CCRASS study.J Am Coll Surg 207:69-69.

- Burke FJ, Main JR, Freeman R (1997) The practice of dentistry: an assessment of reasons for premature retirement. Br Dent J 182:250-254.

- Dodds DW, Cruz OA, Israel H (2013) Attitudes toward retirement of ophthalmology department chairs. Ophthalmology 120:1502-1505.

- Goldberg R, Thomas H, Penner L (2011) Issues of concern to emergency physicians in pre-retirement years: a survey. J Emerg Med 40:706-713.

- Hill KB, Burke FJ, Brown J, Macdonald EB, Morris AJ, et al. (2010) Dental practitioners and ill health retirement: a qualitative investigation into the causes and effects. Br Dent J 209:E8.

- Reuben DB, Silliman RA (1988) Lessons from elderly physicians: reflections on practice, changes in medicine, and retirement. Journal of Applied Gerontology 7:49-59.

- Luce A, Zwanenberg VT, Firth-Cozens J, Tinwell C (2002) What might encourage later retirement among general practitioners?. J Manag Med16:303-310.

- TD, Raymond M, Kosty M, Satele D, Horn L (2014) Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J Clin Oncol 32:1127-1135.

- Deitch CH, Sunshine JH, Chan WC, Owen JB, Shaffer KA, et al. (1995) How US radiologists use their professional time: factors that affect work activity and retirement plans. Radiology 194:33-40.

- Landon BE, Reschovsky JD, Pham HH, Blumenthal D (2006) Leaving medicine: the consequences of physician dissatisfaction. Med Care 44:234-242.

- Orkin FK, Mcginnis SL, Forte GJ, Peterson MD, Schubert A, et al. (2012) United States anesthesiologists over 50: retirement decision making and workforce implications. Survey of Anesthesiology117: 953-963.

- Fletcher SL, Schofield DJ (2007) The impact of generational change and retirement on psychiatry to 2025.nBMC Health Services Research7: 141.

- Onyura B, Bohnen J, Wasylenki D, Jarvis A, Giblon B, et al. (2015) Reimagining the self at late-career transitions: how identity threat influences academic physicians’ retirement considerations. Acad Medn90:794-801.

- Wakeford R, Roden M, Rothman A (1986) General practitioners' retirement plans and what influences them. BMJ 292:1307-1309.

- FH, Andrew JE, Awramenko M, Coutts H, Leighton-Beck L, et al. (2004) Consultants in NHS Scotland: a survey of work commitments, remuneration, job satisfaction and retirement plans. Scott Med J 49:47-52.

- Grauer H, Campbell N (1983) The aging physician and retirement.Can J Psychiatry28:552-554.

- Meghea C, Sunshine JH (2006) Retirement patterns and plans of radiologists. AJR 187:1405-1411.

- Baker FM (1994) Retirement planning by black psychiatrists.J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 7:184-188.

- Rowe ML (1989) Health, income, and activities of retired physicians.N Y State J Med 89:450-453.

- Kalleberg AL (1977) Work values and job rewards: a theory of job satisfaction. American Sociological Review42:124-143.

- Taylor P, Oka M, Rolland L (2004) Work and retirement in the Asia–Oceania region: Perspectives on longer employment and flexible retirement. Geriatrics & Gerontology International4: S190-S193.

- Kim JE, Moen P (2002) Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: a life-course, ecological model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci57:P212-22.

- Noone JH, Stephens C, Alpass FM (2009) Preretirement planning and well-being in later life a prospective study. Research on Aging 31:295-317.

- Wong JY, Earl JK (2009) Towards an integrated model of individual, psychosocial, and organizational predictors of retirement adjustment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 75: 1-3.

- Barrick MR, Mount MK, Li N (2013) The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics. Academy of Management Review 38:132-53.

- Chambers M, Colthart I, McKinstry B (2004) Scottish general practitioners' willingness to take part in a post-retirement retention scheme: questionnaire survey. BMJ 328:329.

- Eagles JM, Addie K, Brown T (2005) Retirement intentions of consultant psychiatrists. BJ Psych Bulletinn29:374-376.

- Rosvold E, Bjertness E (2001) Physicians who do not take sick leave: hazardous heroes?Scand J Public Health29:71-75.

- Davidson JM, MacDonald R, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Parkhouse J (2002) senior doctors' career destinations, job satisfaction, and future intentions: questionnaire survey commentary: are contented doctors good doctors?. BMJ325: 685-686.