Keywords

Advanced maternal age pregnancy; Adverse maternal outcomes; Ethiopia

Introduction

Pregnancy in Advanced Maternal Age (AMA) is a pregnant women who has an estimated delivery date established for a time when a mother is ≥ 35 years [1,2]. In low and middle income countries and South Africa, 12.3% and 17.5% of pregnancies occurred at AMA level [3,4]. Increased AMA population, postponing marriage until later, the availability of better contraceptive options, social and cultural shifts and career advancement have impacted AMA prevalence [5,6]. Fertility is reduced as women age, with a significant reduction in ovarian oocyte reserves after the age of 35 years [5,7]. Globally, adverse pregnancy outcomes are the major causes of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and represent a gap in the ability to reach sustainable developmental goals targets [8,9].

Evidences showed that AMA pregnancy was associated with increased risk of pregnancy induced hypertension (gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and eclampsia), antepartum hemorrhage (APH), gestational diabetis mellitus (GDM) and premature rapture of membrane (PROM). Alongside with this, it is also significantly associated with malpresentation, post-partum hemorrhage (PPH), cesarean delivery, maternal near-miss and metarnal death [10,11]. Most of these outcomes are related to the aging process alone, even though coexisting factors are common [12]. Even though AMA pregnancy associated with these adverse maternal outcomes, some literatures have reported inconsistent results and failed to support.

Despite these adverse maternal outcomes of AMA pregnancy, the research focus given to maternal outcomes of these populationsspecifically in Ethiopia is limited [13] and unable to control confounding variables. Therefore, this study is the first study done which was aimed to compare adverse maternal outcomes among women with adult and AMA pregnancy. In a country like Ethiopia where striving to reduce maternal mortality in 2030, investigating such under studied topic will have paramount input for future maternal health improvement especially in the study area where such research not done. Any gaps in maternal morbidity and mortality may inform policy makers and program implementers, to pass evidence based informed decisions and target maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Methods

Study design, area and period

Institutional based comparative cross sectional study was conducted at Awi zone public hospitals, Northwest, Ethiopia. There are five public hospitals and 47 health centers that serve for a total population of 1,077,144 [14]. This study was conducted from February 25/2020 to April 25/2020.

Study population and eligibility criteria

All women with the age of ≥ 20 years old who gave birth at 28 weeks of gestation or greater in Awi zone public hospitals were included in this study. Those women with age range of 20-34 years old (inclusive) were grouped as adult aged women while 35 years old and above were classified as advanced aged women.

Sample size and sampling procedure

Sample size was calculated using double population formula using Epi-info version 7. Using cesarean section among adult (19.4%) and AMA (32.7%) [13], and assumptions (95% two sided level of confidence, a power of 80%, 2 to 1 ratio of adult and AMA and 10% non-response rate), 447 mothers (149 advanced age and 298 adult mothers) were considered. All five public hospitals found in Awi zone were included in this study. The previous year two months average delivery report of each hospitals with similar season was used to proportionally allocate the sample size. Systematic random sampling technique was employed.

Definition of outcomes

Advanced maternal age: is considered when maternal age is greater or equal to 35 years old [15,16] Adult maternal age: is considered when maternal age is 20-34 years -inclusive [17,18].

Data collection tool and procedure

Data collection tool was adapted after reviewing different related articles and documents [17,19-23]. The questionnaire was translated in to local language (Agew). The tool was pretested and reviewed with senior researchers to check reliability and validity. Structured questionnaire was used to collect the data. Mother’s sociodemographic data, obstetric related data, life style and chronic medical disease related data were included in the tool.

Data quality assurance, processing and analysis

Training was given for data collectors and supervisors. Data collectors were supervised throughout the course of data collection period. The collected data were entered using Epi data version 3.1 computer program and exported to IBM statistical package of social sciences version 25 for analysis. Chi square and independent t-test were computed. Logistic regression analysis were conducted to assess association between adverse obstetric outcomes and maternal age. Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with their corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) was used to declare the presence of association while p-value <0.05 was used to declare statistical significance.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of Medicine and Health Science, Bahir Dar University. Responsible officials and managers at Zone, District and Hospitals were communicated. The collected data were kept in the form of file in secured place and used only for study purpose.

Results

Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics

In this study, a total of 447 participants were included giving a response rate of 100%. The mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of adult and advanced aged mothers was 25.8 (± 3.02) and 37.6 (± 2.9) years respectively. More than half 94 (63%) of AMA women had no education compared to 53 (17.8%) adult aged women. Nearly 38% (56) of advanced aged women had previous bad obstetrical history, compared with 14 (10%) adult aged women. Only 52 (35.9%) advanced aged women were initiate ANC at 12 weeks or before compared to 169 (55.7%) adult aged women. Similarly, significant percentage of advanced aged women 21.5% (32) had chronic medical illness compared to 7.7% (23) of adult aged women. In contrast, there was no significant differences between advanced aged and adult women regarding tetanus toxoid vaccination and iron folate supplementation (Table 1).

| Variables |

Advanced age (149) |

Adult age (n=298) |

Total (n=447) |

| Frequency (%) |

Frequency (%) |

Frequency (%) |

p-value |

| Residence |

Urban |

50 (33.6%) |

208 (69.8%) |

258 (57.7%) |

<0.001 |

| Rural |

99 (66.4%) |

90 (30.2%) |

189 (42.3%) |

| Marital status |

Single |

2 (1.3%) |

8 (2.7%) |

10 (2.2%) |

0.634 |

| Married /union |

146 (98%) |

288 (96.6%) |

434 (97.1%) |

| Others* |

1 (0.7%) |

2 (0.7%) |

3 (0.7%) |

| Maternal education |

Illiterate |

94 (63.1%) |

53 (17.8%) |

147 (32.9%) |

<0.001 |

| Primary |

28 (19.6%) |

115 (38.6%) |

143 (32%) |

| Secondary and above |

27 (18.1%) |

130 (43.6%) |

157 (35.1%) |

| Ethnicity |

Amhara |

149 (100%) |

296 (99.3%) |

445 (99.6%) |

0.316 |

| Others** |

0 |

2 (0.7%) |

2 (0.4%) |

| Religion |

Orthodox |

148 (99.3%) |

291 (98.2%) |

439 (98.2%) |

0.162 |

| Others*** |

1 (0.7%) |

7 (2.3%) |

8 (1.8%) |

| Maternal occupation |

House wife |

48 (32.2%) |

135 (45.3%) |

183 (40.9%) |

<0.001 |

| Farmer |

81 (54.4%) |

62 (20.8%) |

143 (32%) |

| Government employ |

13 (8.7%) |

56 (18.8%) |

69 (15.4%) |

| Othersa |

7 (4.7%) |

45 (15.1%) |

52 (11.6%) |

| Husband occupation |

Farmer |

99 (66.4%) |

79 (26.5%) |

178 (39.8%) |

<0.001 |

| Government employ |

28 (18.8%) |

79 (26.5%) |

107 (23.9%) |

| Merchant |

12 (8.1%) |

89 (29.9%) |

101 (22.6%) |

| Othersb |

10 (6.7) |

51 (17.1%) |

61 (13.6%) |

| Family monthly income (ETB) |

Mean ± SD |

2664 ± 306 |

4758 ± 910 |

4060 ± 769 |

<0.001 |

| Birth interval |

<24 months |

18 (12.2%) |

24 (17.3%) |

42 (14.6%) |

0.221 |

| ≥24 months |

130 (87.8%) |

115 (82.7%) |

245 (85.4%) |

| Previous bad obstetrical history |

Yes |

56 (37.8%) |

14 (10%) |

70 (24.3%) |

<0.001 |

| No |

92 (62.2%) |

126 (90%) |

218 (75.7%) |

| No of pregnancy |

Singleton |

142 (95.3%) |

293 (98.3%) |

435 (97.3%) |

0.063 |

| Twin |

7 (4.7%) |

5 (1.7%) |

12 (2.7%) |

| Status of pregnancy |

Planned |

90 (60.4%) |

271 (90.9%) |

361 (80.8%) |

<0.001 |

| Unplanned |

59 (39.6%) |

27 (31.4%) |

86 (19.2%) |

| ANC follow up |

Yes |

145 (97.3%) |

294 (98.2%) |

439 (98.2%) |

0.313 |

| No |

4 (2.7%) |

4 (1.3%) |

8 (1.8%) |

| GA when start ANC |

≤ 12 weeks |

52 (35.9%) |

169 (57.5%) |

221 (40.3%) |

<0.001 |

| >12 weeks |

93 (64.1) |

125 (42.5%) |

218 (49.7) |

| Tetanus toxoid vaccine |

Yes |

139 (93.3%) |

285 (95.6%) |

424 (94.9%) |

0.289 |

| No |

10 (6.7%) |

13 (4.4%) |

23 (5.1%) |

| Iron folate supplementation |

Yes |

142 (95.3%) |

282 (94.6%) |

424 (94.9%) |

0.762 |

| No |

7 (4.7%) |

16 (5.4%) |

23 (5.1%) |

| Male partner involvement |

Yes |

89(59.7%) |

176 (59.1%) |

265 (59.3%) |

0.896 |

| No |

60 (40.3%) |

122 (40.9%) |

182 (40.7%) |

| Gravidity |

Mean ± SD |

5.37 ± 1.87 |

1.72 ± 0.96 |

2.94 ± 2.18 |

<0.001 |

| Parity |

Mean ± SD |

4.9 ± 1.72 |

1.79 ± 1.86 |

2.84 ± 2.33 |

<0.001 |

| GA at delivery |

Mean ± SD |

38.73 ± 2.06 |

39.05 ± 1.45 |

38.94 ± 1.69 |

0.036 |

| Onset of labor |

Spontaneous |

112 (75.7%) |

252 (84.8%) |

364 (81.8%) |

0.009 |

| Induced |

36 (24.3%) |

45 (15.2%) |

81 (18.2%) |

| Fetal presentation |

Vertex |

144 (96.6%) |

285 (95.6%) |

429 (96%) |

0.610 |

| Othersc |

5 (3.4%) |

13 (4.4%) |

18 (4%) |

| Chronic medical illness |

Yes |

32 (21.5%) |

23 (7.7%) |

55 (12.3%) |

<0.001 |

| No |

117 (78.5%) |

275 (92.3) |

392 (87.7%) |

|

*Divorced and widowed, **Oromo and Benishangul Gumz,***Muslim and protestant, aStudent, merchant and private employ, b Private employ and driver cBreech, shoulder and face

Table 1 Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics of mothers who gave birth in Awi Zone Public Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: 2020.

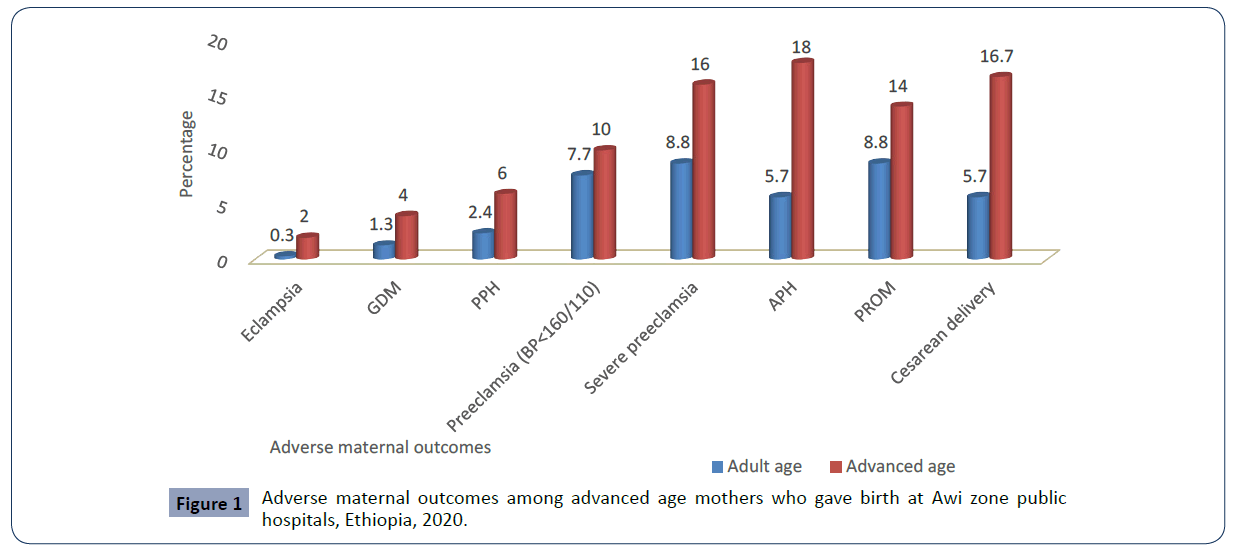

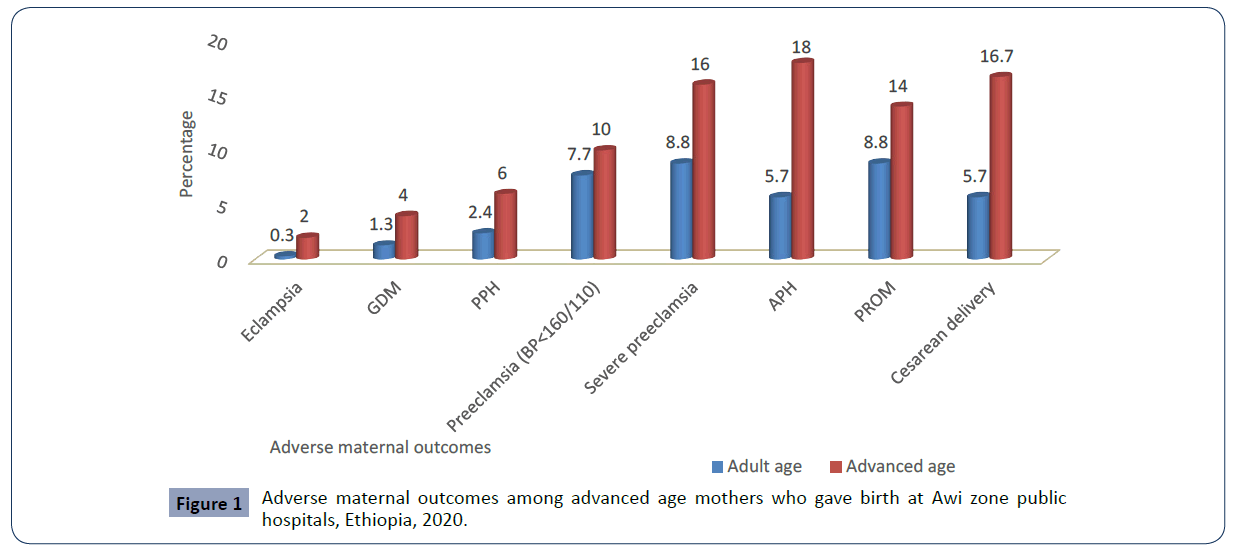

Magnitude of adverse maternal outcomes

Twenty four (16%) advanced aged women had severe preeclampsia, compared to 26 (8.8%) of adult aged women. Similarly, antepartum hemorrhage was significantly more common among advanced aged women 18% (27) compared to adult aged women 5.7% (17). In addition, significant percentage of advanced aged women (16.7%) gave birth through cesarean section compared to adult women (5.7%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Adverse maternal outcomes among advanced age mothers who gave birth at Awi zone public hospitals, Ethiopia, 2020.

Association of advanced age and adverse maternal outcomes

Model fitness was tested with Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test and fit with P=0.932.

The odds of GDM among advanced aged women was 4.36 times higher when compared with adult aged women (AOR=4.36, 95% CI: 1.18, 6.14 with p-value=0.027). Consistently, the likelihood of severe preeclampsia among advanced aged women was 2.42 times higher when compared with adult aged women (AOR=2.42, 95% CI: 1.30, 4.50 with p-value=0.005). In addition, women with advanced aged were 3.10 times more likely to have antepartum hemorrhage when compared with the reference group (20-34) (AOR=3.10, 95% CI: 1.47, 6.54 with p-value=0.003). Moreover, the odds of cesarean delivery among advanced aged women was 3.07 times higher when compared with advanced aged women (AOR=3.07, 95% CI: 1.52, 6.19 with p-value=0.002) (Table 2).

| Variables |

Maternal age |

| Frequency (%) |

COR (95% CI) |

AOR (95% CI) |

p-value |

| 20-34 |

35+ |

| GDM |

4 (1.3%) |

6 (4%) |

3.08 (0.85, 11.1) |

4.36 (1.18, 6.14) |

0.027* |

| Preeclampsia (BP<160/90) |

23 (7.7%) |

15 (10%) |

1.33 (0.67, 2.64) |

1.38 (0.67, 2.84) |

0.37 |

| Severe preeclampsia |

26 (8.8%) |

24 (16%) |

2.00 (1.10, 3.63) |

2.42 (1.30, 4.50) |

0.005** |

| Eclampsia |

1 (0.3%) |

3 (2%) |

6.10 (0.62, 42.1) |

4.60 (0.42, 50.0) |

0.20 |

| Antepartum hemorrhage |

17 (5.7%) |

27 (18%) |

3.65 (1.92, 6.95) |

3.10 (1.47, 6.54) |

0.003** |

| PROM |

26 (8.8%) |

21 (14%) |

1.55 (0.84, 2.87) |

1.20 (0.57, 2.51) |

0.61 |

| Cesarean delivery |

17 (5.7%) |

25 (16.7%) |

3.33 (1.73, 6.39) |

3.07 (1.52, 6.19 |

0.002** |

| Postpartum hemorrhage |

7 (2.4%) |

9 (6%) |

2.62 (0.97, 7.32) |

2.35 (0.79, 7.00) |

0.12 |

* Significant at P<0.05, ** Significant at P<0.01

Table 2 Logistic regression of the association between advanced maternal age and adverse maternal outcomes in Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

Discussion

The present study revealed that advanced maternal age was significantly responsible for deiffrent adverse maternal outcomes. Accordingly, the odds of GDM among advanced aged women was significantly higher when compared to adult aged women. This result is in line with studies conducted in Barcelona [24], China [25], United Kingdom [26] and Turkey [21]. The possible explanation could be the fact that advanced age is associated with endothelial damage and well known cardiovascular risk factor that produces structural and functional changes in the vasculature in turn increases the risk of developing insulin resistance [11,27].

In addition, the likelihood severe preeclampsia was significantly higher among advanced aged women when compared with adult aged women. This result is in line with findings of studies held in Sweden [12], Japan [22], Malaysia [16] and Tigray [13]. This is could be due to AMA is associated with decrease of endothelial response to vasodilators [10,28].

According to the present study, advanced aged women were at higher risk for antepartum hemorrhage. The odds of antepartum hemorrhage was significantly higher among advanced aged women when compared to the reference group (20-34). This finding is consistent with studies done in Canada [23], Japan [22], South Korea [29] and Tigray [13]. This could be due to AMAis associated with increased gravidity, parity and cesarean scar which in turn make them at greater risk of having placental abruption and placenta previa [30].

Moreover, advanced maternal age was significantly associated with cesarean delivery. The odds of cesarean delivery was significantly higher among advanced aged women when compared to adult aged women. This is supported with findings of studies done in China [25], United Kingdom [20], Calfornia [31] and South Africa [3].This could be due to inefficiency of the aging myometrium, decreased number of oxytocin receptors, increased rates of chronic medical diseases and maternal complications such as preeclampsia and GDM [32,33].

Conclusion

Generally, odds of adverse maternal outcomes among advanced aged women were higher when compared to adult aged women. Thus, the odds of GDM, severe preeclampsia, APH and cesarean delivery were significantly higher among advanced aged women compared to adult aged women. In adding this, substantial proportion of preeclampsia (BP<160/110 mmhg), eclampsia, PROM and PPH were seen among advanced aged women when compared to adult women.

Therefore, Ethiopian Ministry of Health should adress provision of quality family planning and perinatal care for all reproductive age women. Finally, longitudinal study evaluating adverse maternal outcomes after 24hr of delivery regardless of delivery setting and gestational age is recommended.

Limitation

Finally, this study shares the limitation of cross sectional study that may not indicate causal relationship. In addition, as the study was done in hospital setting, maternal outcome of women who gave birth at home was not assessed. Finally, our study misses adverse outcomes after 24hr of birth.

Declaration

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Institutional Review Board of Bahir Dar University’s College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Then, officials at different levels in the hospitals were communicated through letters from College of Medicine and Health Science. Confidentiality of the information was secured throughout the study process.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding

There were no external organizations that funded this research.

Authors’ contribution

TG developed the project. TG, AN, GD, MD and MA participated in the methodology, data analysis and developing the initial drafts of the manuscript and revising subsequent drafts. TG and AA prepared the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Science to have Ethical clearance. The authors would aslo like to extend their gratitude to Awi Zone public hospitals for their valuable contribution.

35554

References

- Larisa C, Amita K, Mahantesh K (2010) Biopanic, advanced maternal age and fertility outcomes. Preconceptional Medicine.

- Rebecca D (2018) Evidence on Advanced Maternal Age. Evidence Based Birth.

- Hoque ME (2012) Advanced maternal age and outcomes of pregnancy: A retrospective study from South Africa. Biomedical Research 23.

- Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, Intarut N, Mori R, Ganchimeg T, et al. (2014) Advanced maternal age and pregnancy outcomes: a multicountry assessment. BJOG 121:49-56.

- Rajput N, Paldiya D, Verma YS (2018) Effects of advanced maternal age on pregnancy outcome. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 7:3941-3945.

- Walker KF, Thornton JG (2016) Advanced maternal age. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 26:354-357.

- Ambrogio PL, Emma R, Carla P, Cagnacci A, DriulL (2019) Maternal age and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 19:261.

- Adane AA, Ayele TA, Ararsa LG, Bitew BD, Zeleke BM (2014) Adverse birth outcomes among deliveries at Gondar University hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14:90.

- Tyas BD, Lestari P, Akbar MIA (2019) Maternal Perinatal Outcomes Related to Advanced Maternal Age in Preeclampsia Pregnant Women. J Family Reprod Health13:191.

- Li Y, Ren X, He L, Li J, Zhang S, et al. (2020) Maternal age and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 120 million participants. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 162:108044.

- Blomberg M, Tyrberg RB, Kjølhede P (2014) Impact of maternal age on obstetric and neonatal outcome with emphasis on primiparous adolescents and older women: a Swedish Medical Birth Register Study. BMJ Open 4:e005840.

- Mehari MA, Maeruf H, Robles CC, Woldemariam S, Adhena T, et al. (2020) Advanced maternal age pregnancy and its adverse obstetrical and perinatal outcomes in Ayder comprehensive specialized hospital, Northern Ethiopia, 2017: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20:60.

- Awi zone health office (2019) Annual activity report of the year 2018/19. Awi zone, Ethiopia Unpublished report 2019.

- Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, Heazell AEP (2017) Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 12:e0186287.

- Rashed HEM, Awaluddin SM, Ahmad N, Supar NHM, Lani ZM, et al. (2016) Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes in Muar, Johor, Malaysia. Sains Malaysiana 45:1537-1542.

- Mekiya E, Tefera B, Fekadu Y, Getu K (2018) Disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes between advanced maternal age and younger age in Ethiopia: institution based comparative cross-sectional study. Int J Nursing and Midwifery 10:54-61.

- Frederiksen LE, Ernst A, Brix N, Lauridsen LLB, Roos L, et al. (2018) Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes at advanced maternal age. Obstet Gynecol 131:457-463.

- Sydsjö G, Pettersson ML, Bladh M, Svanberg SA, Lampic C, et al. (2019) Evaluation of risk factors’ importance on adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in women aged 40 years or older. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19:92.

- Louise K, Lavender T, McNamee R, O'Neill SM, Mills T, et al. (2013) Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: evidence from a large contemporary cohort. PloS one 8:e56583.

- Bekir K, Rauf M, Evruke IC, Cetin C (2018)The effect of advanced maternal age on perinatal outcomes in nulliparous singleton pregnancies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18:343.

- Ogawa K, Urayama KY, Tanigaki S, Sago H, Sato S, et al. (2017) Association between very advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a cross sectional Japanese study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17:349.

- Wu Y, Chen Y, Shen M, Guo Y, Wen SW, et al. (2019)Adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes among singleton pregnancies in women of very advanced maternal age: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19:3.

- Nieto MC, Barrabes EM, Martínez SG, Prat MG, Zantop BS (2019) Impact of aging on obstetric outcomes: defining advanced maternal age in Barcelona. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19:342.

- Shan D, Qiu PY, Wu YX, Chen Q, Li AL, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women of advanced maternal age: A retrospective cohort study from China. Scientific Reports 8:12239.

- Khalil A, Syngelaki A, Maiz N, Zinevich Y, Nicolaides KH (2013) Maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 42:634-643.

- Lao TT, HoLF, Chan BC, Leung WC (2006) Maternal age and prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 29:948-949.

- Lamminpää R, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Gissler M, Heinonen S (2012) Preeclampsia complicated by advanced maternal age: a registry-based study on primiparous women in Finland 1997–2008. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12:47.

- Koo YJ, Ryu HM, Yang JH, Lim JH, Lee JE,et al. (2012) Pregnancy outcomes according to increasing maternal age. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 51:60-65.

- Roustaei Z (2017) Advanced maternal age and placenta previa for women giving birth in finland; a register-based cohort study. Master Thesis, University of Eastern Finland.

- Osmundson SS, Gould JB, Butwick AJ, Yeaton-Massey A, El-Sayed YY (2016) Labor outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology214: e361-362.

- Bayrampour H, Heaman M (2010) Advanced maternal age and the risk of cesarean birth: a systematic review. Birth 37:219-226.

- Rydahl E, Declercq E, Juhl M, Maimburg RD (2019) Cesarean section on a rise—Does advanced maternal age explain the increase? A population register-based study. PloS one 14:e0210655.