Keywords

Empathy, nursing students, compassion, nurses, Jefferson Scale of empathy.

Introduction

Over the last three decades, there has been growing interest of exploring the concept of empathy in relation to patient care. Empathy is complex, multi-dimensional phenomenon [1,2]. It has been conceptualized in a variety of ways, including as a natural and intrinsic trait and as a learned phenomenon [2]. Empathy is the capacity to participate vicariously and understand the experience and emotions of others [3,4]. Clarifying the concept of empathy through the literature identified five conceptualizations of empathy as: a human trait, a professional state, a communication process, caring and a special relationship. Yu & Kirk [5] state that these conceptualizations reflect both the intrinsic and acquired aspects of empathy, as described by Alligood [6] and Spiro [7], and the key elements of empathy (moral, emotive, cognitive and behavioral components) summarized by Morse et al [8]. The cognitive element shows the ability to identify and understand others’ perspectives and depict their thoughts, the emotive element reflects the ability to experience and share in others’ psychological states or intrinsic feelings, the moral aspect relates to an internal altruistic drive that motivates the practice of empathy, and the behavioral element shows the ability to communicate empathetic understanding and concerns [9]. Moreover, empathy is defined as awareness and insight into the feelings, emotions, and behavior of another person and their meaning and significance [2].

Some people by nature are more empathic than others and therefore the ability to empathize varies from one individual to another [5]. However, acquired empathy can be taught as a skill and developed with practice and experience [6,7]. It has been also stressed that empathy is an essential component of a caring relationship and especially critical to the provision of quality nursing care [10]. Researchers agree on the positive role empathy plays in interpersonal relationships when providing health care. Its values in a therapeutic relationship have been emphasized, relationships in which healthcare professionals understand the feelings of patients as if they themselves were the patients [1,11]. However, studies have shown that healthcare professionals often ignore patients’ direct and indirect emotional expressions and miss opportunities to express empathy [12,13].

There is clearly debate in the literature about what may contribute to empathy and how it can be assessed, improved and sustained [5]. LaRocco [2] states that in an increasingly technological health care setting, empathetic actions on the part of the healthcare provider will make the difference between a cold, sterile experience and a humanistic interaction. LaMonica et al., [14] found less anxiety, depression and hostility in cancer patients being cared for by nurses who show high levels of empathy. In addition, it has been reported that the quality of client’s disclosure was found to be associated with the level of empathy used by nurses [15]. Moreover, Reynolds and Scott [15] state that empathy is crucial to the fundamental aim and achievement of nursing goals.

The majority of the studies carried out previously have focused on: empathy levels of nurses, variations in empathy between health professionals as well as the relationship between empathy and a variety of variables of participants [5]. However, there few studies exploring the concept of empathy in nursing students. The results of existing studies exploring nurses’ empathy show inconsistent results, with some researchers reporting low levels of empathy [16,17] and moderately well-developed empathy being noted in others [18,19]. Other studies reported a relatively high level of self-reported nurses’ empathy [18-24].

Astrom et al., [20] examined the relationship between burnout, empathy and attitudes towards patients with dementia in a sample of 358 (N=358) registered nurses, licensed practical nurses and nurse aids working in community settings, psychogeriatric clinic and somatic long term care in Sweden. Empathy was associated with burnout (r= -0.19) and nurses’ attitudes (r= -0.29). Overall nurses showed moderate level of empathy. Registered nurses had significantly higher scores than nurses’ aides (P=0.005).

Warner [22] assessed the relationship between nurses’ (N=20) self-reported empathy levels and patients’ (N=28) satisfaction with nursing care in medical and surgical units in a hospital situated in the United States. The results showed that nurses’ had moderate levels of empathy which were not related to patients’ satisfaction with nursing care. A study conducted in Australia examined the relationship between critical care nurses’ (N=183) empathy and variables as such gender, years of practice in critical care, level of education and occupational position. The results showed moderately well-developed empathy among critical care nurses. Female had slightly higher scores than males. There were no significant differences in empathy with respect to years of practice, educational levels, and current position [18].

Gunther et al., [25] explored the relationships between leadership styles and empathy (cognitive and affective levels) in 178 nursing students (N=178). The mean empathy scores appeared to be similar between junior and senior students. Becker and Sands [26] in a descriptive study carried out in United States found that male nursing students reported lower level of empathy.

The relationship between students’ empathy levels and their attitudes towards minority ethnic patients was explored in a descriptive study conducted in a university in the United States [27]. 122 nursing students (N=122) participated and no relationship between empathy and attitudes towards patients from ethnic minority groups was found.

Watt-Watson et al., [19] carried out a study in a cardiovascular unit in a hospital in Canada in order to examine the relationship between nurses’ empathy levels and patients’ pain intensity and analgesic administration after surgery. Eighty (n=80) patients and (n=80) nurses participated. It was found that nurses had moderate empathy levels, which did not significantly affect the pain intensity of their patients or analgesia administered. It also found that empathy was related to nurses’ knowledge and beliefs about pain management (r=0.37, p<0.001).

Hodges Selwyn [28] carried out an experiment for the development of empathy in student nurses with the expectations that following an empathetic training the rated performance of the nursing students would increase. Surprisingly, the findings of the study showed that empathy was not increased or decreased. However, the authors acknowledged a number of limitations of the methods used which justified the results of the study. In contrast, several studies have found that experiential training during nursing students’ studies significantly increased empathy between second and fourth year students [29]. Similarly, a quasi-experimental research study on undergraduate students receiving a 12 day short skills-based counseling experiential training found statistically significant improvement in empathy scores after the training [30].

Lauder et al., [31] in a comparative study of three cohorts of 185 (N=185) students on mental health, adult and learning disability branches found that there were no statistically significant differences in perceptions of empathy among three cohorts of students. The highest levels of self-reported empathy were found in the third year student cohort, whereas lower levels of empathy were found in the second year students. However, these differences were not statistically significant.

Kliszer et al., [32] utilised Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) students’ version to assess Polish physicians, nursing students, medical students, midwives students and nurses. Physicians and nursing students displayed the highest empathy levels whereas nurses displayed the lowest. There was no difference in gender in terms of empathy level between participants.

Yu and Kirk [9] referring to other researchers’ work stated that higher empathy levels of nurses or nursing students have often been associated with positive patient outcomes, such as reduced distress and anxiety levels and increased likelihood of identifying the perceived needs of patients and carers [17,33,34,35].

Though the concept of empathy has been explored in health care professionals including nurses in different countries, there are no known studies investigating it in Greece. Given that nurses first come into contact with the concept of empathy during their undergraduate studies it is essential to investigate Greek nursing students’ levels of empathy. The findings around nursing students’ levels of empathy could provide vital information for restructuring the nursing curricula so as to ensure the cultivation of empathic skills of nursing students.

The study

The main aim of the present study was to identify nursing students’ level of empathy at one Greek nursing school.

Objective

To explore variables influencing nursing students’ empathy ability.

Methods

Study design

This study utilized a descriptive cross-sectional survey design to collect data from Greek nursing students, using a self-administered questionnaire. The data were collected in January 2009. Study participation was anonymous and voluntary.

Sample and research site

The study population consisted of a convenience sample. A total of 279 Greek student nurses (N=279) of first (1st), third (3rd), fourth (4th) and sixth (6th) semester studies participated in the study with 77.5% response rate. Participants were studying general nursing in a nursing school of a Technical Educational Institute which belongs to the higher education system in Greece. The duration of nursing studies was 8 semesters. The researchers approached students in their classrooms and invited them to participate in the study. After explaining the purpose of the study the researchers distributed a self-administered anonymous questionnaire to students who were willing to participate. In addition, the students were reassured that their responses would be confidential and their participation was voluntary. Moreover, the nursing students were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. The completed questionnaires were placed in sealed envelopes, deposited in a box and collected by researchers over a period of 3 weeks.

Instrument

The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section comprised the Jefferson scale of empathy for nursing students which measures the level of nursing students’ empathy. The second section contained a set of demographic valuables as well as questions related to nursing students’ empathy abilities. In addition, participants asked to rate themselves according to their empathetic ability from not at all empathetic (1) to very empathetic (7).

The Jefferson Scale of Empathy for Nursing Students

This scale was adopted from the Jefferson Scale of Physicians Empathy (JSPE) which developed and slightly modified to measure empathy among medical students and physicians [36,37]. The scale is a self-administered 20-item psychometrically validated scale designed to measure empathy of nursing students. Respondents rate their level of agreement with each statement on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1=Strongly Disagree to 7= Strongly Agree). The scale can be completed in 5-10 minutes. Ten items of the scale are positively worded and therefore scored in accordance to the likert weight (from 1=Strongly Disagree to 7= Strongly Agree) and the rest 10 items were negatively worded thus, reversed scored (Strongly Agree =1 to Strongly Disagree =7) [38]. Negatively worded items are usually used in psychological tests in order to decrease the confounding effect of the acquiescence response style, a tendency to constant endorse “agree” (or “disagree”) responses to the items [39]. The scales’ possible score can range from a minimum of 20 to a maximum of 140.

The higher the score the higher the participants’ levels of empathy.

The scale has been used in medical students [36,37,40] and reported construct and criterion related validity. The coefficient alpha reliability for the JSPE ranged from .80 to .89 for samples of medical students [36,40]. Convergent validity of the scale was confirmed by higher correlations between empathy scores and conceptually relevant measures such as compassion (r=.48) for medical students [36].

In order to use the Jefferson Scale of Nursing students Empathy (JSNSE) permission was requested by Center for Research in Medical Education and Health Care in Philadelphia. For the purpose of the present research some modifications were made to adapt the scale to assess empathy of Greek nursing students. Adaptations were made in wording to make the text consistent with the Greek culture, without losing intended key concepts. The JSNSE was first modified by the authors so the wording of the items applied directly to nursing students. In all items of the scale the word “Nurses’ was replaced by rewording the item from impersonal to the first person structure. The change of impersonal to the first person structure aimed to stimulate respondents’ responsibilization and their response to capture their empathetic ability. For instance the 1st item of the scale “Nurses’ understanding of their patients’ feelings and the feelings of their patients’ families does not influence medical or surgical treatment” was recorded as follows “my understanding as a nursing student of how patients and their families feel does not affect my provision of nursing care”. The scale was first translated from English to Greek by the authors and two independent bilingual researchers who have not seen the original version. In addition, the back translation procedure was performed by three bilingual nurse researchers. The authors and the three other nurse researchers compared the original English version with the back translated Greek version to detect inconsistencies. The authors and bilingual researchers resolved any inconsistency so as the scale was consistent with the Greek culture and language without losing intended key concepts. A panel of three experts evaluated the validity of the scale and reported that it appear to have face and content validity.

Reliability estimation of the Jefferson Scale of Physicians Empathy (for Nursing Students) had been shown that the scale had good internal consistency (a=0.78).

The second section of the questionnaire comprised demographic questions with respect to sex, age, semester of studying, nationality, religion, and religiosity. In addition, respondents were asked some other personal questions such as their willing to work as nurses after their graduation, and if it was their preference to studying nursing. Respondents were also asked if they had the ability to sense others’ perspective, if they had taken emotional care of their nuclear family, if they had received during their studies training in understanding patients’ perspectives. Moreover, they were asked if their clinical instructors approached patients with emotional understanding skills. Furthermore, a seven point scale was developed in which respondents asked to self-assessing their ability to understand emotionally their patient.

Pilot study orientation

The feasibility and acceptability of the questionnaire were tested in a pilot study of 20 student nurses from semesters which were not involved in the main study. Overall the pilot study showed that no major changes in structure or content of the questionnaire were needed.

Ethical issues

Students were informed about the purpose and the benefits of carrying out the study and advised that participation was voluntarily, and the questionnaire was anonymous. Students were advised that they could decline to participate or could withdraw at any time without detriment to their studies and were informed that the completion of the questionnaire implied consent to participate in the study.

Data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were undertaken in analysing the data. Chi-square test was utilised to determine the relationship between gender and nursing students’ level of empathy. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to analyse differences between, year of respondents study, nationality, religiosity and other personal as well as empathic variables. Tests were considered statistically significant at the level of 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for windows version 17.

Results

Sample

A total of 279 nursing students in their 1st, 3rd, 4th and 6th semesters participated in the present study. Of the respondents 14.2% (n=40) were male and 85.8% (n=239) were female. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 37 years with a mean age of 20.92 years (SD=2.78). The majority of nursing students were in either 6th (n=94/33.6%) or 1st (n=81/29%) semesters, whilst less students were in their 3rd (n=57/20.4%) or 4th (n=47/17%) semesters. With respect to respondents’ nationality the majority were Greek (n=262/94%), 2.5% (n=7) were Albanian, 1.1% (n=3) were Cypriots and 2.2% (n=7) not stated. The majority of the respondents 50.2% (n=140) rated themselves as religious, 31.7% (n=89) as fairly religious, 11,2% (n=31) as very religious, with a proportion of 6.9% (n=19) as not at all religious. In regard to religious preference the majority of nursing students (n=262/94.1%) were Christian, 1.9% (n=5) were Muslim and 4% (n=12) not stated. Of the respondents 86.5% (n=241) reported that they will work as nurses after their graduation. 74.9% (n=208) stated that studying nursing was their preference and they were not forced by anyone. Respondents were also asked if they had the ability to understand others’ perspectives. Of the participants 51,4% (n=81), reported that some time they have the ability to empathize others, 29.2% (=81) reported that definitely respondents had the ability, a lower proportion that they don’t have it at all and 13.9% (n=40) reported that their empathetic ability depends on their emotional state. 52.4% of the participants stated that they had taken emotional care of their nuclear family where as 41.9% reported that they had taken enough. When respondents were asked if they thought that their instructors approached patients’ empathically, 54.9% reported that their instructors displayed empathic skills occasionally. 33.3% reported that their instructors don’t display empathic skills and only 11.8% stated that they found empathic skills in their instructors.

Nursing students’ empathy level

The total mean score of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy for Nursing Students was 88.63 (SD=8.93). Participants overall reported a moderate degree of empathy.

In addition, the mean score of the 7 point scale of respondents self-assessment level of emotional understanding of patients was 5.06 (SD=1.04). The mean score of the single item scale indicates that nursing students self-assessed their emotional understanding higher than the overall mean score of their empathy level.

Empathy level and gender

A Chi-square test showed that female respondents displayed more empathetic ability in relation to the men, in a statistically significant level (68.1% vs 67.7%; x2 =283.203, df=4, P=0.001).

Variables related to nursing students’ empathy

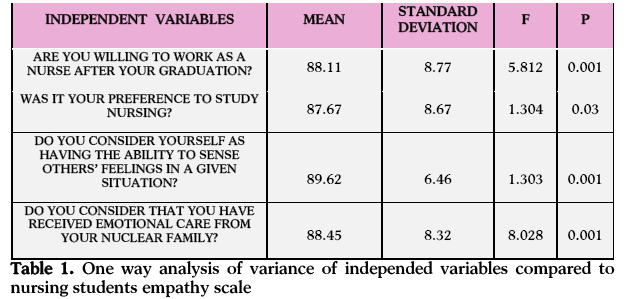

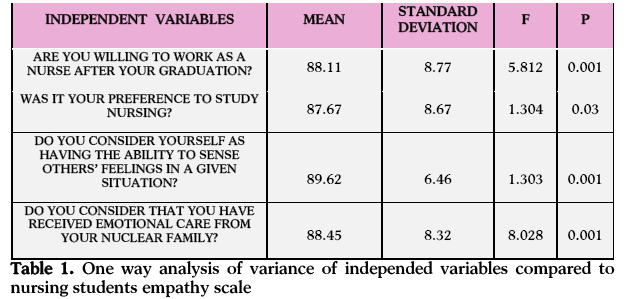

One way analysis of variance showed nursing students who willing to work as nurses after their graduation displayed more empathy at a statistical significant level (P<0.001) compared to nursing students who reported that they were not willing to work as nurses. Nursing students who reported that it was their preference to study nursing, displayed statistically significant (P<0.03) higher levels of empathy.

The respondents who reported that they had the ability to sense others’ feelings in a given situation displayed statistically significant higher empathy levels (P<0.001). In addition, respondents who reported they had received emotional care from their family showed statistically significantly higher empathy levels (P<0.001) (Table 1).

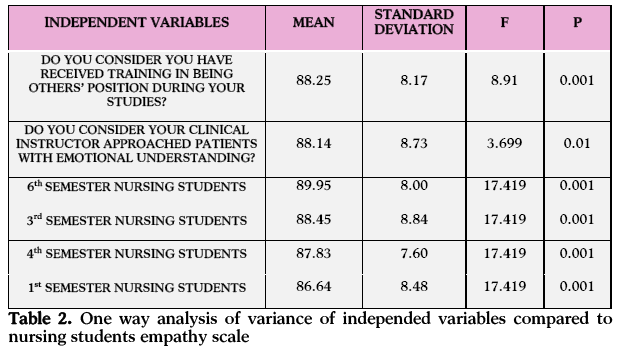

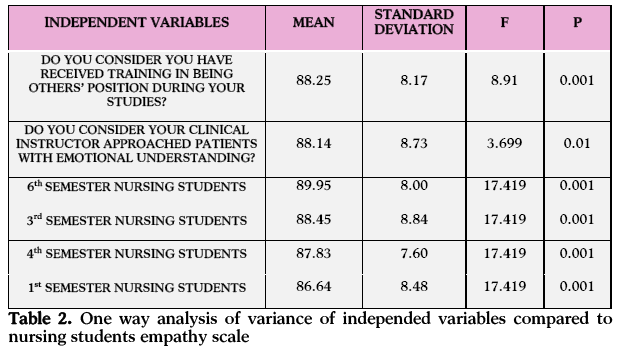

Nursing students who reported that they had received training during their studies about being in others’ position displayed statistically significant more empathy (P<0.001). Respondents answering that their clinical instructors approached patients with emotional understanding displayed statistically significant higher empathy levels (P<0.01). In addition, older nursing students showed statistically significant higher levels of empathy compared to younger ones (P<0.001). Especially, nursing students studying in the 6th semester (third year) displayed higher empathy levels than those in the 3rd semester and the 4th. The least empathy level displayed in nursing students of the 1st semester of their studies (Table 2).

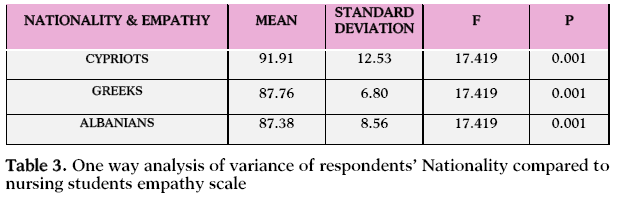

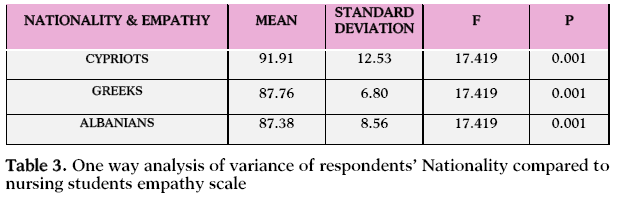

With respect to nursing students’ nationality the results showed that nursing students from Cyprus displayed statistically significant higher empathy levels than the Greek students, with the least empathy demonstrated by Albanian students (P<0.001) (Table 3).

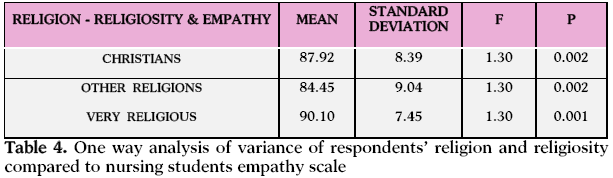

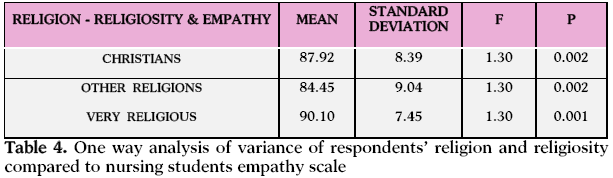

The results showed that the variable religion and the level of religiosity had an impact on nursing students’ levels of empathy. In particular, Christian nursing students demonstrated statistically significant higher empathy levels than other believers (P<0.002). Moreover, respondents who stated that they were very religious displayed statistically significant higher empathy levels (P<0.001) (Table 4).

Discussion

Nursing students appear to have moderate levels of empathy which is commonly reported by other studies [26,31,32]. Given that Greek nursing students in the present study had not received additional training to enhance their empathetic skills the results showed the students were familiar with the concept of empathy. In fact, according to the nursing curriculum they had been taught about the concept in health psychology in their first semester looking at the meaning as well as the importance of empathy in the nursing profession and practice. In addition, some of the students had attended an optional module on “nursing counseling” in which the concept of empathy had been explained and taught extensively. Furthermore, the majority of the respondents’ were from the 6th semester which included the module of “mental health nursing” in which students are trained theoretically and practically in a clinical placement to approach patients with medical, psychological or psychiatric difficulties.

The value of training in empathy is obvious in the results of the present study. Although some believe that empathy is an innate charisma, many studies indicate that it can be increased through appropriate experiential education [29,30,41]. In addition, studies conducted with both students of nursing and qualified nurses show that empathy is a skill that can be learned through education [28,42,43].

It also has to be stressed that a vast majority of the respondents (86.5%) reported that they were willing to work as nurses and a similar proportion stated that it was their preference to studying nursing. Thus, nursing students had already formed a caring personality which is compatible with the elements contributing to empathetic ability. Especially, when respondents were asked if they had received emotional care from their families the majority responded positively. Therefore, students’ families “worked” as a “model” of empathetic human beings which would help them to further enhance that ability. Similarly, respondents who reported that their clinical instructors approached patients with emotional understanding displayed more empathetic ability. This confirms the value of the role model of a skilled clinical instructor who could guide nursing students and train them in empathetic approach by example.

Nursing students self-reported higher for their ability to understand emotionally the patients. The result could be justified by the fact that respondents easier respond to a single item as it should be and therefore not really spontaneously.

With respect to gender female nursing students displayed more empathetic ability compared to their male counterparts. This result is in keeping with other studies found that females have significantly higher empathy scores compared to males [26,44,45,46]. In contrast, Kliszer et al., [47] found that in terms of gender there was no difference in nursing students’ level of empathy. However, the theory on women’s sensitivity to others emotional states and accepting attitudes has been confirmed in the literature [47].

Concerning respondents’ level of semester and empathy level found that the higher the semester the more empathy nursing students self-reported. Similarly, Lauder et al., [31] found that the third year of cohort students self-reported higher level of empathy. The level of semester was found to influence nursing students’ empathy positively. In fact more mature students in the third year of their studies had more opportunities to be trained and enhancing empathetic skills compared to junior nursing students.

An interesting finding was that the effect of ethnicity on empathic ability. Students from Cyprus showed more empathy level compared to Greeks and Albanian, which can be explained by the fact that as a nation Cyprus has faced a tragedy which might influence them to develop more empathetic ability.

In addition, the present study found that Christians nursing students self-reported high level of empathy. Moreover, nursing students with strong religious beliefs displayed higher empathy levels. This finding is partially supported in the literature, with some studies demonstrating a relationship between religiosity and empathy [48] and other study showing no relationship between the variables [49].

The results of the present study confirm that the concept of empathy is multidimensional and there are many factors affecting it. Therefore, nursing students in their undergraduate studies can start fostering empathy by being encouraged to become aware of others’ feelings and to see situations from alternative points of view. In order for nursing students to develop empathy it is necessary to utilize reflection during their training in order to be aware of the way they understand patients’ views or current situation. Moreover, while empathy is considered an important attribute of nurses it has to be taught in a way that it is evaluated and therefore incorporated into clinical teaching on the nursing students’ clinical training.

Limitations of the study

The study utilized a cross-sectional self-assessment scale which only measures empathy intent and not actual empathetic behavior [50]. However, it has to be acknowledged that the present study was exploratory in nature attempting to gather preliminary information on nursing students’ empathy level as well as potential influential factors.

In a future research study the sample would be expanded to include more nursing schools gathering more information on the empathy level of Greek nursing students. A longitudinal study design from 1st semester of nursing students, following them into their final year of study, would provide invaluable information about curricula content which could be revised whenever considered necessary.

Conclusions

Empathy as a concept is complex, multi-dimensional and there are different variables that influence nursing students’ attitudes and behaviour displaying empathic skills. Furthermore, empathy is a skill that can be cultivated by nursing studies and it is a necessary part of nursing students’ theoretical and clinical training. Given that nursing students are the future change agent and reformers of the health care system, it is vital to explore the factors related to or influencing the concept of empathy further to develop nursing curricula, integrating specific training in order to enhance nursing students’ actual empathic skills.

3189

References

- Alligood MR. Rethinking empathy in nursing education: shifting to a developmental view. Annual Review of Nursing Education 2005; 3:299-309.

- LaRocco SA. Assisting nursing students to develop empathy using a writing assignment. Nurse Educator 2010; 35(1):10-11.

- Carper BA. Fundamental patterns of knowing in Nursing. Advances in Nursing Science 1978; 1 (1):13-23.

- Kunyk D, Olson JK. Clarification of conceptualizations of empathy. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2001; 35(3):317-325.

- Yu J, Kirk M. Measuring of empathy in nursing research: a systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2008; 64(5):440-454.

- Alligood MR. Empathy: the importance of recognizing two types. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 1992; 30(3):14-17.

- Spiro H. What is empathy and can it be taught? Academia and Clinic 1992; 116(10):843-846.

- Morse JM, Anderson G, Bottorff JI. Exploring empathy: a conceptual fir for nursing practice? Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship 1992; 24(4):273-280.

- Yu J, Kirk M. Evaluation of empathy measurement tools in nursing: systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2009; 65(9):1790-1806.

- Reynolds WJ, Scott B, Jessiman WC. Empathy has not been measured in clients’ terms or effectively taught: a review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1999; 30 (5): 1177-1185.

- Hojat M, Gonnella J, Nasca T, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: Definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. American Journal of Psychiatry 2002; 159(9): 1563-9.

- Suchman A, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA 1997; 277(8):678-846.

- Levinson W, Corawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA 2000; 284(8):1021-1027.

- LaMonica E, Wolf R, Madea A, Oberst M. Empathy and nursing care outcomes. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice 1987; 1(3):197-213.

- Reynolds WJ, Scott B. “Do nurses and other professional helpers display much empathy? Journal of Advanced Nursing 2000; 31(1):226-234.

- Daniels TG, Denny A, Andrews D. Using microcounceling to teach RN nursing students skills of therapeutic communication. Journal of Nursing Education 1988; 27(6):246-252.

- Reid-Ponte P. Distress in cancer patients and primary nurses’ empathy skills. Cancer Nursing 1992; 15 (4):283-292.

- Bailey S. Levels of empathy of critical care nurses. Australian Critical Care 1996; 9(4):121-122, 124-127.

- Watt-Watson J, Garfinkel P, Gallop R, Stevens B, Streiner D. The impact of nurses’ empathic responses on patients’ pain management in acute care. Nursing Research 2000; 49(4):191-200.

- Astrom S, Nilsson M, Norberg A, Winblad B. Empathy, experience of burnout and attitudes towards demented patients among nursing staff in geriatric care. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1990; 15:1236-1244.

- Astrom S, Nilsson M, Norberg A, Sandman P, Winblad B. Staff burnout in dementia care relations to empathy and attitudes. International Journal of Nursing Studies 1991; 28(1):65-75.

- Warner RR. Nurses’ empathy and patients’ satisfaction with nursing care. Journal of New York Nurses Association 1992; 23(4):8-11.

- Kyremyr D, Kihlgrein M, Norberg A, Astrom S, Karlsson J. Emotional experiences, empathy and burn out among staff caring for demented patients at a collective living unit and a nursing home. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1994; 19(4):670-679.

- Palsson MB, Hallberg IR, Norberg A, Bjorvell H. Burnout, empathy and sense of coherence among Swedish district nurses before and after systematic clinical supervision. Scandinavian Journal of caring Science 1996; 10(1):19-26.

- Gunther M, Evans G, Mefford I, Coe TR. The relationship between leadership styles and empathy among student nurses. Nursing Outlook 2007; 55(4):196-201.

- Becker H, Sands D. The relationship of empathy to clinical experience among male and female nursing students.

- Louie K. Empathy, anxiety and transcultural nursing. Nursing Standard 1990; 24(5):36-40.

- Hodges SA. An experiment in the development of empathy in student nurses. Journal of advanced Nursing 1991; 16(11):1296-1300.

- Çınar N, Gevahir R, Şahin S, Sözeri C, Kuğuoğlu S. Evaluation of the empathic skills of nursing students with respect to the classes they are attending. Revista Electronica de Enfermagem 2007; 9(3):588-595.

- Cutcliffe J, Cassedy P. The development of empathy in students on a short, skills based counseling course: A pilot study. Nurse Education Today 1999; 19(3):250-257.

- Lauder W, Reynolds W, Smith A, Sharkey S. A comparison of therapeutic commitment, role support, role competency and empathy in three cohorts of nursing students. Journal of Psychiatric Mental health Nursing 2002; 9(4):483-491.

- Kliszer J, Nowicka-Sauer K, Trzeciak B, Nowak I, Sadowska A. Empathy in health care providers-validation study of the Polish version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. Advances in Medical Sciences 2006; 51:219-225.

- Murphy PA, Forrester DA, Price DM, Monagham JF. Empathy of intensive care nurses and critical care family needs assessment. Heart and Lung 1992; 21(1):25-30.

- Olson JK. Relationships between nurses-expressed, empathy patient perceived empathy and patient distress. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 1995; 27(4):317-322.

- Olson J, Hanchett E. Nurse-expressed empathy, patient outcomes, and development of a middle-range theory. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 1997; 29(1):71-76.

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Rattner S, Erdmann JB, Gonnella JS et al. An empirical study of decline of empathy in medical school. Medical Education 2004, 38 (9):934-941.

- Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Veloski JJ, Erdmann JB et al. Empathy in medical students as related to academic performance, clinical competence, and gender. Medical Education 2002; 36(6):522-527.

- Ward J, Schaal M, Sullivan J, Bowen ME, Erdmann JB, Hojat M. Reliability and Validity of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy in Undergraduate Nursing Students. Journal of Nursing Measurement 2009; 17(1):73-88.

- Hojat M. Empathy in patient care: Antecedents, development, measurement, and outcomes. New York: Springer, 2007.

- Kataoka H, Koide N, Ochi K, Hojat M, Gonnella J. Measurement of empathy among Japanese medical students: psychometrics and score differences by gender and level of medical education. Academic Medicine 2009; 84(9): 1192-1197.

- Wikstrom BM. Work of art dialogues: An educational technique by which students discover personal knowledge of empathy. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2001; 7(1):24-29.

- Mete S. The empathetic tendencies and skills of nursing students. Social Behavior and Personality 2007; 35(9):1181-1188.

- Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Academic Medicine 2009; 84(9):1182-1191.

- Shapiro J, Morrison E, Boker J. Teaching empathy to first year medical students: evaluation of an elective literature and medicine course. Education for Health 2004; 17(1):73-84.

- Williams A. Empathy and burnout in male and female helping professionals. Research in Nursing & Health 1989; 12(3):169-178.

- Kliszer J, Hebanowski M, Rembowski J. Emotional and cognitive empathy in medical schools. Acad. Med. 1998; 73(5):541.

- Duriez B. Are religious people nicer people? Taking a closer look at the religion empathy relationship. Mental health Religion & Culture 2004; 7(3):249-254.

- Watson PJ, Hood RW, Morris RJ, Hall JR. Empathy, religious orientation and social desirability. Journal of Psychology 1984; 117:211-216.

- Spencer J. Decline in empathy in medical education: how can we stop the rot? Med Educ, 2004; 38(9): 916-918.