Mesude Kisli* and Ahmet Yard?m

Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Numune Hospital, Sivas, Turkey

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Mesude Kisli

Department of Neurology, Numune Hospital, Sivas, Turkey

Tel: +905055722806

E-mail: mesudekisli@yahoo.com

Rec Date: September 28, 2018; Acc Date: November 13, 2018, 2018; Pub Date: November 19, 2018

Citation: Kisli M, Yard?m A (2018) An Interesting Eating Epilepsy Case Induced by Bread Eating. J Neurol Neurosci Vol.9 No.6:276.. doi:10.21767/2171-6625.1000276.

Keywords

Bread; EEG; Eating epilepsy; MRI; Reflex epilepsy

Introduction

Eating epilepsy is a rare type of reflex epilepsy. The reflex epilepsies include those epileptic syndromes consisting of seizures that are triggered by specific stimuli usually a clearly recognized somato-sensitive or sensory one. Eating epilepsy is an uncommon form of these. Several physio-pathological mechanisms involved in the genesis of these seizures have already been discussed. Eating epilepsies represent a heterogeneous group with variable clinic and EEG findings. This case presented here was an eating epilepsy case triggered by bread eating and implicated, based on EEG and MRI.

Case Report

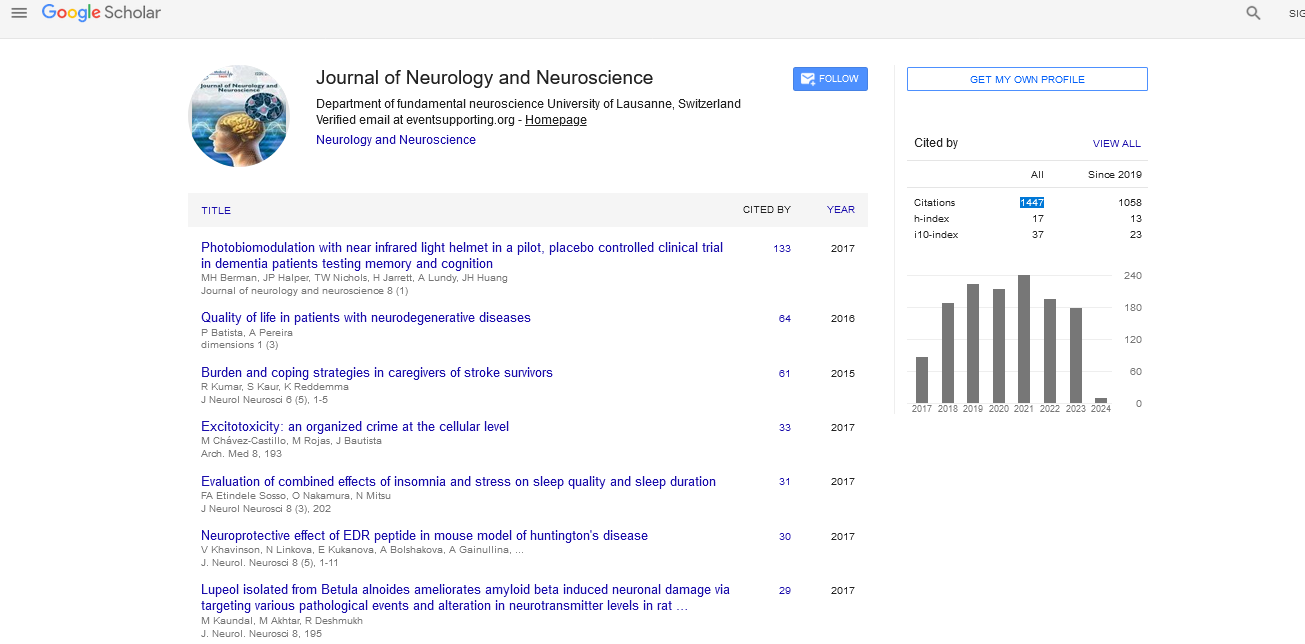

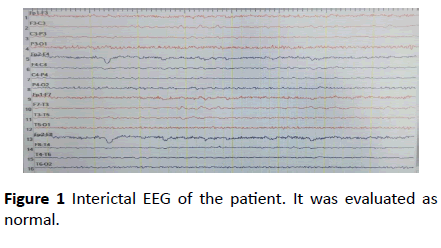

At twenty-eight years woman applied to our hospital second time with the reason for the strange movements that took place in her body. In her anamnesis, she has described focal aware seizures in the form of curling and turning in her hands and slight right turn her head during bread eating for the last 9 years. She said that her seizures occured 30-40 sec just after she started to eat bread (almost during every bread eating) and lasted 40 sec-50 sec. There was no loss of consciousness during seizures. She had focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure and loss of consciousness following her left-hand trembling 2 times in the last 2 months during sleeping at night. With these complaints, the patient had applied to different centers before. The EEGs in those centers are evaluated as normal. The anti-epileptic drug had not been started because it may be psychogenic. This patient’s seizures also had not been observed before as there was no bread-eating activity did not take place during the examination. We did not detect any obvious abnormality in the physical and neurological examination of the patient except mild mental retardation. There was no abnormality except low vitamine D (9 ng/ml) in routine blood biochemistry. The performed EEG in our hospital did not show epileptic focus (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Interictal EEG of the patient. It was evaluated as normal.

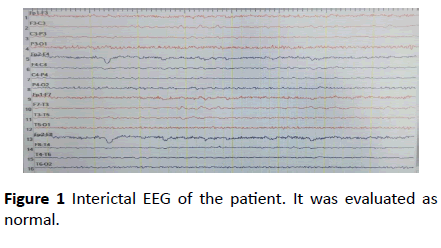

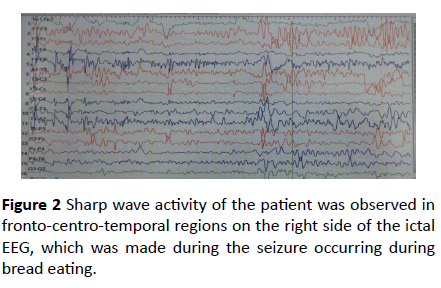

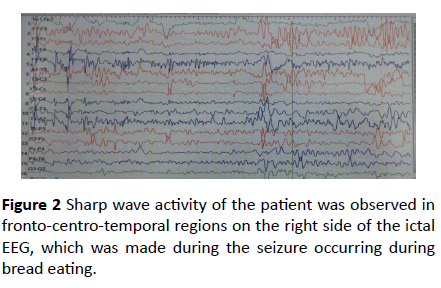

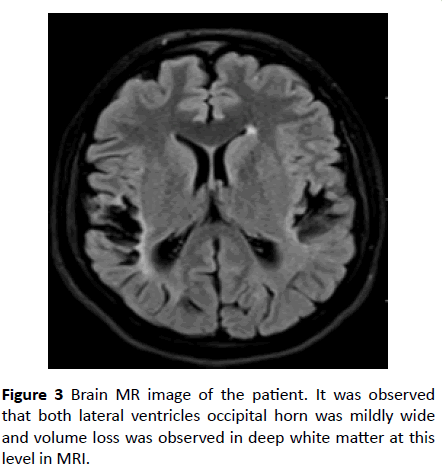

Because the previous routine EEG recordings were normal, it was decided that EEG recording was obtained by feeding bread to the patient. Written consent of the patient and her relatives has been obtained. Only a piece of bread was eaten. In the second bite, a focal aware seizure, which started as a twist in her hands and turned her head slightly to the right, was observed and EEG was performed (Figure 2). A focal aware seizure was also seen during the ictal EEG. In the meantime, she responded short answers to the questions. No loss of consciousness. Her swallow paused. This seizure lasted about 30 seconds. Sharp wave activity was observed in the more pronounced fronto-centro-temporal regions on the right side of the ictal EEG. An encephalomalacic area in the bilateral parietal cortical region was observed in MR (1,5 Tesla) images (Figure 3). With these findings, the patient was diagnosed with reflex epilepsy [1,2].

Figure 2 Sharp wave activity of the patient was observed in fronto-centro-temporal regions on the right side of the ictal EEG, which was made during the seizure occurring during bread eating.

Figure 3 Brain MR image of the patient. It was observed that both lateral ventricles occipital horn was mildly wide and volume loss was observed in deep white matter at this level in MRI.

The patient was informed about seizure triggering foods. Levetiracetam 1000 mg/day (in two equal doses) was started to the patient. And then she was followed. After 2 months, she had partial control of her seizures. The drug is increased the desire to 2000 mg/day (in two equal doses).

Discussion

RE are clinically very similar to unprovoked seizures, except for the presence of specific stimuli. The prevalence of RE ranges from 4% to 7% for all epilepsy patients and up to 21% in idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Seizures triggered by eating are very rare, and their estimated prevalence is nearly 1/1,000-2,000 among all patients with epilepsy. Physiopathological mechanisms are complex. Seizures are closely related to stereotyped eating behavior, which may differ from a patient to another. Seizure triggers include reading, writing, other language functions, startle, somatosensory stimulation, proprioception, auditory stimuli, immersion in hot water, eating, and rotatory stimulation. A number of sensory stimuli are recognized as causes of reflex epilepsy, including eating [3]. Eating is a complex phenomenon involving psychological, sensory, proprioceptive, and enteroceptive stimuli [4]. Eating epilepsy (EE) is a unique yet debilitating reflex epilepsy with discrete electroclinical signs and mechanisms [3]. Bulky meals rich in carbohydrates have been postulated as possible triggering factors. Eating may also trigger periodic spasms in some disorders such as infantile epileptic encephalopathy, focal symptomatic epilepsy, or MECP2 duplication syndrome, possibly by activating the frontalopercular region that evokes the activity of the brainstem or the regions responsible for seizure initiation. Rarely, the smell of food, eating too much or heavy meals, and gastric distension can cause a seizure. Seizures are focal, start short after beginning to eat, and do not repeat during the same meal. In reflex epilepsies usually, there is a trigger event in patients’ history [5]. Our patient also had a history of feverish disease at 3 years of age. Three types of reflex epilepsy are described; those induced by simple stimuli, complex stimuli, or higher cerebral functions [2]. EE is described in association with congenital malformations, vascular abnormalities, post-infective lesions, and neoplasms such as astrocytoma and glioblastoma [4]. Functional imaging techniques such as PET, SPECT, and EEG-fMRI provide the potential to image epileptic activity [2]. Abnormal EEG observed in patients with epilepsy is reflected by interictal epileptiform discharge, commonly called the "epileptic spike" [2]. EEG has focal epileptiform abnormalities, which may be secondarily generalized and originate from temporolimbic or suprasylvian structures. Seizures localized to suprasylvian area can also occur with proprioceptive and somatosensory stimuli as well as with other oral activities [1]. MR and EEG findings of our patient were correlated and support these observations mentioned above.

It has been emphasized in most of the patients who describe eating epilepsy that the seizures were observed during the function of eating (75%), after eating (10.7%) or after eating and afterwards (14.3%). Reflex seizures can be either generalized or focal, with or without impairment of awareness. Our patient seizures provoked by only bread eating. The seizures started after 30-40 second following bread eat. This form of epilepsy depending on bread eating should consider as depend on carbohydrates. The patient developed gustative, chewing and salivation stimulations with bread and this was occurred during the recording in the EEG. In our patient, if the bread is mixed with other foods, seizures do not occur. This condition is considered to be an extremely rare condition. Spontaneous seizures may also be seen in patients with eating epilepsy [5]. Our patient had two times focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures while sleeping except her eating in my elaborate anamnesis.

It has been reported that seizures are controlled by monotherapy in 50-70% of patients [5]. LEV 500 mg 2 × 1 was given after our diagnosis and partial control of seizures was achieved. After 1 month the dose was increased to 2 × 1000 mg, follow-up and treatment are continuing.

Conclusion

To our knowledge our case is unique in that firstly, it is a case of eating epilepsy which starts with bread eating and develops against other food after a long time. This case tells us that this type of reflex epilepsy shows can start only against some sort of carbohydrate and then increase against other food.

Conflict of Interest

Author Mesude Kisli declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author Ahmet Yard?m declares that he has no conflict of interest. The authors whose names are listed immediately above certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. All procedures performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

23736

References

- Okudan ZV, Özkara Ç (2018) Reflex epilepsy: Triggers and management strategies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 14: 327-337.

- Sandhya M, Bharath RD, Panda R, Chandra SR, Kumar N, et al. (2014) Understanding the pathophysiology of reflex epilepsy using simultaneous EEG-fMRI. Epileptic Disord 16: 19-29.

- Jagtap S, Menon R, Cherian A, Baheti N, Ashalatha R, et al. (2016) Eating epilepsy revisited-An electro-clinico-radiological study. J Clin Neurosci 30: 44-48.

- Remillard GM, Zifkin BG, Andermann F (1998) Seizures induced by eating. Reflex epilepsies and reflex seizures: Advances in neurology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, USA.

- Ayas ZO, Boluk A (2017) A rare epilepsy type: Eating epilepsy. Epilepsy 23: 81-83.