Mohamed Ali Gliti1,3*, Najoua Belhaj2,3, Sophia Nitassi2,3, Bencheikh Razika2,3, Mohamed Anas

Benbouzid2,3, Abdelilah Oujilal2,3 and Leila Essakalli Houssyni2,3

1 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Ibn Sina University Hospital, Rabat, Morocco.

2 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Ibn Sina University Hospital, Rabat, Morocco.

3 Mohammed V University, Rabat,

Morocco.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mohamed Ali Gliti

Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat, Mohammed V University, Rabat, Morocco

E-mail: mohamed.ali.gliti@gmail.com

Received Date: March 10, 2021; Accepted Date: March24, 2021; Published Date: March 31, 2021

Citation: Ali Gliti Md, Belhaj N, Nitassi S, Razika B, Benbouzid MA, et al. (2021) Anterior Rhinorrhea Revealing Meningocele: A Case Report. Transl

Biomed Vol.12 No.3:163

Keywords

Rhinoliquorrhea; Osteo-meningeal breccia; Meningocele; Fat graft; Endoscopic surgery

Introduction

The osteomeningeal breaches of the anterior level of the base of the skull involve the different walls separating the subarachnoid spaces from the nasal cavity, and can be responsible for cerebrospinal rhinorrhea in this air cavity. They are evoked by the presence of a "rock water" flow localized to the nasal cavities.

They are most often secondary to trauma to the base of the skull. Their severity is linked to the risk of meningitis (10%-25% of cases), brain abscesses, and pneumocephalus. Their diagnosis is clinical, biological, and radiological.

Currently, cerebral Computed Tomography (CT) and brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are the techniques best suited to these requirements. They also allow a preoperative assessment to be made in which all the anatomical variants will be mentioned.

The repair of the breach by endoscopic endonasal route has increasingly taken the place of external routes, in particular neurosurgical routes, obtaining success rates of 85% to 90% in almost all the series published since 1990 mainly by otorhinolaryngologists (ENT). Regardless of the repair technique used endoscopically, the success rate is approximately 90%. This technique preserves olfactory function, limits morbidity, and operative mortality.

Case Report

This is a 37-year-old patient, followed for poorly controlled asthma, treated with inhaled and oral corticosteroid therapy, the patient reported on questioning three antecedents of head trauma with three different points of impact: occipital, frontal, and temporal.

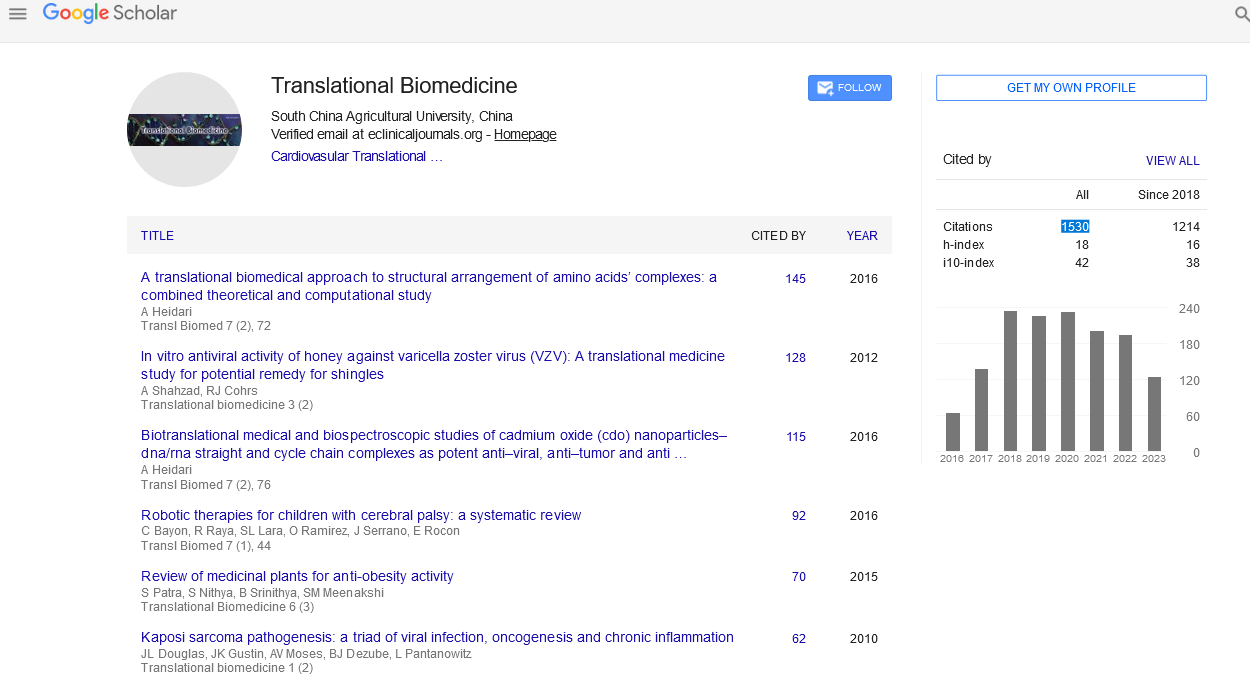

Symptoms started 2 years ago with the onset of pneumococcal meningitis, after which the patient was hospitalized in the neurology department. A year later, the patient had a second episode of meningitis, or a brain MRI was requested showing an osteomeningeal breach (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The patient was started on Acetazolamide (Diamox 250 mg), postural measures, and anti-meningococcal vaccines.

Figure 1: Images of the nasal sinus high-resolution CT scan in coronal section showing the osteomeningeal breach at the anterior level of the base of the skull (arrow).

Figure 2: Nasosinus MRI images in the T2 sequence confirming the anterior location of the breach on the left side (arrow).

A depletive lumbar puncture was subsequently performed and referred to the ENT department for surgery.

Clinical examination found intermittent, rock-water clear rhinorrhea in the left nasal cavity, exacerbated by closed glottis efforts (defecation, cough, sneezing, etc.) without other associated rhinological signs. The initial nasal endoscopic examination was unremarkable.

The patient underwent exploratory endoscopic surgery where a meningocele was individualized at the level of the anterior part of the base of the skull on the left (Figure 3), then the breach was sealed with organic glue and abdominal fat and organic glue. The immediate postoperative period is marked by the disappearance of the rhinorrhea as well as four months of follow-up after the operation.

Figure 3: Intraoperative endoscopic image showing the outcome of the meningocele through the osteomeningeal breach (arrow).

Discussion

The osteo-meningeal breach is a fairly common disease of multiple etiology. Its incidence varies between 4.6 and 7.6 cases per year in the United States in 2004 and 9 cases per year in Belgium in 2008 [1-3]. In the study by Bell et al [1,2] the mean age ranged from 28 to 49 years with a predominance of men.

Rhinoliquorrhea can be primary or secondary, in Schlosser's series, secondary rhinoliquorrhea represented 96% of cases [4]. Craniofacial trauma is the main etiology, and 10% of cases are from iatrogenic causes [4-6]. In the study by Eljamel et al., 63% of rhino-liquorrhea were of traumatic origin [6]. Traumatic causes may be related to skull base surgery at a rate varying between 42% and 66.66% [2-7].

Rhinoliquorrhea can also occur amid tumors of the nasal cavity [8]. Primary rhinorrhea may be linked to a deformity of the anterior and middle level of the base of the skull, also linked to inflammatory causes, or erosive breaches linked to an arachnoid cyst [9]. Otoliquorrhea is less frequent but often traumatic [8]. They represented 8 out of 23 cases and were mainly the result of a traffic accident in our study.

High-resolution CT scan and MRI are of great benefit in locating and evaluating lesions, aiding in surgical guidance when necessary to avoid invalid explorations. Isotope cisternography during flow is more invasive and is performed after the intranasal injection of fluorescein [9-11]. These explorations were carried out and made it possible to locate breccias of the ethmoid and/or sphenoid [2, 12-14].

Biochemical analysis of cerebrospinal fluid is essential in cases of mild or intermittent discharge and when high-resolution CT is not helpful [15-18]. Conventional biochemical analyzes of protein or glucose in the discharge may indicate the presence of cerebrospinal fluid. But they require a large sample and have the drawback of being deactivated in the event of blood contamination. Likewise, the determination of bedside secretion glucose test strips has low sensitivity and specificity but can be useful in an emergency when framed by the trace of transferrin ß2 and β-protein [16]. None of these biological tests could be performed in our context.

The therapeutic management of osteo-meningeal involvement must take into account the cause, the anatomical site, the size of the defect, the age of the patient, and the underlying intracranial pressure. This management combines the rest of the patient and antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce the risk of developing meningitis [11-13].

Surgery is the second part of the treatment. It consists of lumbar punctures and drainage that promote spontaneous healing. But in the event of the persistence of the flow or multiple post-traumatic breaches, plugging of the site is carried out with a bone graft, a temporal fascia, or abdominal fat. The endoscopic route is currently the most practiced because of the aesthetic benefit and the conclusive results in the management of the osteomeningeal breach of the anterior part of the cranial base, as several authors testify [3,17,18]. The external neurosurgical approach is more rarely indicated in cases of severe anomaly [2].

Conclusion

The causes of osteo-meningeal breaches are dominated by trauma to the base of the skull, more rarely caused by inflammatory or tumor phenomena of the nasal cavities. They are manifested by rhinoliquorrhea or otoliquorrhea. Their management is symptomatic medical treatment associated with surgery, most often by the endoscopic route.

36439

References

- Bell RB, Dierks EJ, Homer L, Potter BE (2004) Management of cerebrospinal fluid leak associated with craniomaxillofacial trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62: 676-684.

- McMains KC, Gross CW, Kountakis SE (2004) Endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Laryngoscope 114: 1833-1837.

- Scholsem M, Scholtes F, Collignon F, Robe P, Dubuisson A, et al. (2008) Surgical management of anterior cranial base fractures with cerebrospinal fluid fistulae: a single-institution experience. Neurosurgery 62: 463-469

- Schlosser RJ, Bolger WE (2004) Nasal cerebrospinal fluid leaks: critical review and surgical considerations. Laryngoscope 114: 255-265

- Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM (2000) Persistent posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Neurosurg Focus 9: e1

- Eljamel MS (1994) Fractures of the middle third of the face and cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Br J Neurosurg 8: 289-293

- Gendeh BS, Mazita A, Selladurai BM, Jegan T, Jeevanan J, et al. (2005) Endonasal endoscopic repair of anterior skull-base fistulas: the Kuala Lumpur experience. J Laryngol Otol 119: 866-874

- Raine C (2005) Diagnosis and management of otologic cerebrospinal fluid leak. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 38: 583-595, vii

- Tosun F, Gonul E, Yetiser S, Gerek M (2005) Analysis of different surgical approaches for the treatment of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 48: 355-360.

- Righini C, Reyt E, Lavieille JP, Passagia JG, Charachon R (1996) Surgical treatment under endoscopic control of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea of sphenoid origin. A propos of 5 cases. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 113: 188-195.

- Schuknecht B, Simmen D, Briner HR, Holzmann D (2008) Nontraumatic skull base defects with spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea and arachnoid herniation: imaging findings and correlation with endoscopic sinus surgery in 27 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29: 542-549.

- Domengie F, Cottier JP, Lescanne E, Aesch B, Vinikoff-Sonier C, et al. (2004) Management of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae: physiopathology, imaging and treatment. J Neuroradiol 31: 47-59

- Schmerber S, Boubagra K, Cuisnier O, Righini C, Reyt E (2001) Methods of identification and localization of ethmoid and sphenoid osteomeningeal breaches. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 122: 13-19

- Bachmann G, Elverland HH, Sørheim SI, Borota L (2003) Diagnosis and surgical treatment of liquorrhea. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 123: 3190-3192

- Eljamel MS, Foy PM (1990) Acute traumatic CSF fistulae: the risk of intracranial infection. Br J Neurosurg 4: 381-385

- Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Kassam AB (2005) The management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks in patients at risk for high-pressure hydrocephalus. Laryngoscope 115: 205-212

- Daele JJ, Goffart Y, Machiels S (2011) Traumatic, iatrogenic, and spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak: endoscopic repair. B-ENT 7 Suppl 17: 47-60.

- Tabaouti K, Kraoul L, Alyousef L, Lahoud GA, Rousset SB, et al. (2009) The role of biology in the diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 67: 141-151.