Keywords

Women friendly care; Accessibility; Affordability; Culturally acceptable; Client satisfaction

Lists of Abbreviations

C/S: Cesarean Section; EDHS: Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey; EOC: Emergency Obstetric Care; IEC: Information, Education and Communication; MDG: Millennium Development Goal; PPS: Probability Proportionate to Sample Size; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SRH: Sexual and Reproductive Health; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

Women friendly care is an approach to care giving with the goal of creating an enabling environment at all level to improve women’s access to safe motherhood and reproductive health services. It is paramount to improving service utilization especially in settings where utilization is low [1]. This approach focuses on the rights of women to have access and get quality care which has in turn has a health benefit for their infants. Therefore, it is considered as part of a broader strategy in reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and requires strong partnerships between governments, health systems and communities [2].

According to a report on women-friendly health services experiences in maternal care, health care service to be defined as women friendly care it must located closely to where women easily access it, cost low, promote providers and offer chances for clients informed decision making concerning the care they received [1].

The lack of ‘women friendliness’ often has greater impact on the health of poorer women who are at greater risk of maternal mortality and morbidity. Poor/illiterate women have less of a voice and may be more vulnerable to neglect, abuse or poor communication, especially when staff are stressed, overworked and under pressure. Women who are disempowered cannot request quality health care nor demand accountability when the services provided are questionable [3].

A woman’s relationship with healthcare providers and the maternity care system during pregnancy and childbirth is vitally important. Not only are these encounters the vehicle for essential and potentially lifesaving health services, women’s experiences with caregivers at this time has the impact to empower and comfort or to inflict lasting damage and emotional trauma, adding to or detracting from women’s confidence and self-esteem. A woman’s memories of their childbearing experiences will stay with them for a lifetime and are often shared with other women, contributing to a climate of confidence or doubt around childbearing [4].

Health care providers need to be able to understand women’s needs and recognize the uniqueness of the birthing experience to each woman and her family including providing care that is culturally sensitive and women friendly [5]. Many studies also show that the presence of women friendly care in a facility can determine labor outcomes for the mother as well as the baby.

The existence of a clinically and administratively sound healthcare provision system does not necessarily ensure the utilization of healthcare services if the mother is dissatisfied with the way care is provided [1].

In Germany, patients reported lack of involvement in the planning of health care process and that they felt they were not being taken seriously. Patients also felt that their diagnoses had not been disclosed empathetically and that they were insufficiently informed about their disease [6].

A study on Zambian women’s experiences of urban maternity care indicated that despite the women reporting 89% good care, 21% reported remembering someone who had treated them badly by shouting or scolding them during labor and one fifth reported having been left alone in the labor room [7].

In a study done at a health centre in Malawi looking at quality of care and its effects on utilization of maternity services at a primary level, a high degree of satisfaction was noted among patients with providers’ attitude (97%), technical competence (86%), and working hours (91%). However, they expressed dissatisfaction with lack of privacy [8].

Recent evidence from the Cochrane systematic reviews however has shown that women friendly care which involves shared control of consultations, decision about interventions or management of the problems with the patient will improve patients’ satisfaction [9].

For most Ethiopian women being pregnant is not just a matter of having a baby, it is a matter of life and death, for her and her baby. Because of this most laboring women prefer to be in an environment where they feel secure, respected and can receive the emotional and physical support from their families and care providers [4].

There are a few previous studies conducted in our country concerning women friendly care and factors associated to it in public health centres. So that, the purpose of this study as advocating for women friendly services is to assess factors associated to women friendly care in patients perspective to improve the quality of health care and the responsiveness of health providers to meet the needs of women.

Materials and Methods

Facility based cross sectional study was conducted on postnatal mothers in three public hospitals of Jimma zone from April-May 2016. Single population proportion formula was used to calculate a sample size, by using 50% of the proportion of expected provision of women friendly care. Systematic random sampling technique was used for selecting study respondents. The total quota of postnatal mothers from each public hospital added up and then proportional allocation to sample size was used based on the calculated sample size for distributing it for each hospital. Finally, based on the total numbers of postnatal mothers of each three public hospitals and calculated sample size, K-value was calculated in which each mothers were selected and interviewed.

Data was collected using structured interviewer administered questionnaires. The instrument comprises in part 1: Basic demographic education and socio-economic with 7 items, pregnancy with 3 items, labor and delivery with 5, postnatal with 3 and overall prenatal care with 17 items.

The collected data was edited, coded, categorized, verified as well as entered into a computer and analysed using SPSS window version 21. The statistical analysis was conducted in two steps namely: Simple (binary) and multivariable logistic regression analysis. Frequency distributions, percentages, cross tabulations between the dependent and independent variables were done. Simple logistic regression analysis was done for all independent and dependent variables one by one using binary logistic regression to see their association. The variables which show significant association on simple analysis with p-value of <0.25 were eligible for multivariable logistic regression. Strength of the relationships (adjusted odds ratio) between specific independent variables and dependent variable were determined by multivariable logistic regression analysis (to control any confounders) with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was declared at P<0.05.Finally, the results were presented in texts, tables and figures.

Ethical clearance was obtained from Ethio-Canada MNCH project, ethical review committee. Prior to data collection for written permission, an official letters were written to each public hospital administrators and communication was made by principal investigator with each public hospitals ward directors.

All study participants were given information on the study in order to obtain their verbal consent before administering questionnaires and assured that all data is confidential and is only analyzed as aggregates. They also informed that they have full right to discontinue or refuse to participate in the study. Answers to any questions of respondents were made completely confidential.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of study subjects

A total of 264 Jimma University specialized, Shenen Gibe and Limmu Genet Hospital respondents participated in the study with the response rate of 99.24%, but 2 (0.76%) of the responses were excluded from the analysis because of their incompleteness.

From the total of 262 respondents, 95 (36.3%) were in the age ranges from 20-24 and most of them, 204 (77.9%) live in home with their husbands/partner while 98 (37.4%) and 91 (34.7%) of respondents and their husbands attended primary school respectively.

The majority of respondents’, 147 (56.1%) main means of transport to health facility was walk/on foot, and 128 (48.9%) of them needed 30 minutes to reach there. 147 (56.1%) of respondents rated their household economic status as moderately poor (Table 1).

| Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Age |

|

|

| 15-19 |

29 |

11.1 |

| 20-24 |

95 |

36.3 |

| 25-29 |

81 |

30.9 |

| 30-34 |

47 |

17.9 |

| >=35 |

10 |

3.8 |

| Who lives within house |

|

|

| Lives alone |

8 |

3.1 |

| Husband/partner |

204 |

77.9 |

| Children |

11 |

4.2 |

| One/more parent |

16 |

6.1 |

| Husband and children |

23 |

8.8 |

| Highest level of school attended by respondent |

|

|

| None |

88 |

33.6 |

| Primary |

98 |

37.4 |

| Secondary |

50 |

19.1 |

| Higher/university |

26 |

9.9 |

| Highest level of school attended by her husband |

|

|

| None |

69 |

26.3 |

| Primary |

91 |

34.7 |

| Secondary |

60 |

22.9 |

| Higher/university |

42 |

16 |

| Main means of transport |

|

|

| Walk/on foot |

147 |

56.1 |

| Public transport |

112 |

42.7 |

| Private vehicle |

3 |

1.1 |

| Length of time needed to reach health facility |

|

|

| 1 -10 minute |

17 |

6.5 |

| 30 minute |

128 |

48.9 |

| 1 hour |

50 |

19.1 |

| >1 hour |

67 |

25.6 |

| Economic status of respondents in their points of view |

|

|

| Very poor |

29 |

11.1 |

| Moderately poor |

147 |

56.1 |

| Rich |

86 |

32.8 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population, Jimma University specialized, Shenen Gibe and Limmu Hospital, Jimma zone, April, 2016, n=262.

Provision of women friendly care

From the total respondents, 186 (71%) of them reported that the care they received during ANC, delivery and Postnatal were based on their needs (provision of women friendly care) while the remaining respondents reported as the care they had been receiving was not women friendly, and the care to be women friendly, 13 (5%) and 12 (4.6%) of them recommended that care providers should be kind, not shout, with good attitude, care with no payment & care providers should be kind, not shout, with good attitude, stay near, care with no payment and clean toilets and bathrooms respectively (Table 2).

| Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Was all maternity services women friendly? |

|

|

| Yes |

186 |

71 |

| No |

76 |

29 |

| If no, what you’d like to see changed? |

|

|

| Care providers should be kind |

2 |

0.8 |

| Care providers should not shout/scold |

5 |

1.9 |

| Care providers should have good attitude |

2 |

0.8 |

| Care should have clean toilets and bathrooms |

3 |

1.1 |

| Care providers should be kind, not shout/scold, have good attitude and no payment |

2 |

0.8 |

| Care providers shouldn't shout, have good attitude and clean toilets and bathrooms |

7 |

2.7 |

| Care providers should be kind, not shout, good attitude, no payment, stay near and Clean toilets and bathrooms |

12 |

4.6 |

| Care providers should be kind, not shout, good attitude, no payment and stay near |

6 |

2.3 |

| Care providers should be kind, not shout, good attitude and no payment |

13 |

5 |

| Care providers should be kind, not shout, no payment and stay near |

5 |

1.9 |

| Care providers should be kind, not shout and no payment |

3 |

1.1 |

| Care providers should have good attitude and no payment |

1 |

0.4 |

| Care providers should be kind and no payment |

1 |

0.4 |

| Care providers should be kind, good attitude and no payment |

3 |

1.1 |

| Care providers should be kind, not shout,have good attitude and stay near |

2 |

0.8 |

| Care providers should be kind,have good attitude, no payment and stay near |

2 |

0.8 |

| Care providers should be kind and shouldn't shout/scold |

1 |

0.4 |

| Care providers should be kind, shouldn't shout,have good attitude and care with Clean toilets and bathrooms |

3 |

1.1 |

| Care providers shouldn't scold and stay near |

3 |

1.1 |

| Was there any one who treated you badly? |

53 |

20.2 |

| Yes |

209 |

79.8 |

| No |

|

|

| What did they do? |

14 |

5.3 |

| Shouted/scolded |

1 |

0.4 |

| Didn't taught well |

6 |

2.3 |

| Examined roughly |

6 |

2.3 |

| Didn't come when called |

8 |

3.1 |

| Shouted/scolded and examined roughly |

2 |

0.8 |

| Shouted/scolded and didn't taught well |

3 |

1.1 |

| Shouted, didn't taught well and came when called |

4 |

1.5 |

| Didn't taught, examined roughly and didn't came when called |

4 |

1.5 |

| Scolded, examined roughly and didn't come when called |

2 |

0.8 |

| Scolded and didn't come when called |

3 |

1.1 |

| Shouted, examined roughly and rushed us |

|

|

| Did you have to pay for anything? |

|

|

| Yes |

99 |

37.8 |

| No |

163 |

62.2 |

| Amount of payment for care received |

|

|

| 50-100 |

53 |

20.2 |

| >200 |

46 |

17.6 |

| Condition of payment |

|

|

| Difficult to find money |

25 |

9.5 |

| Quite difficult to find money |

47 |

17.9 |

| Not difficult to find money |

27 |

10.3 |

Table 2: Provision of women friendly care among study population, Jimma University specialized, Shenen Gibe and Limmu Hospital, Jimma zone, April, 2016.

Antenatal care follow up

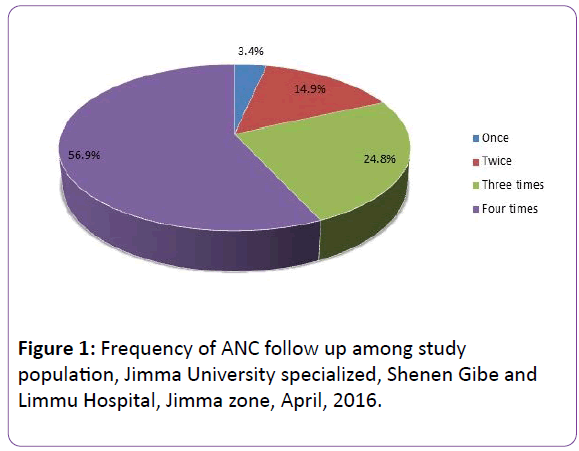

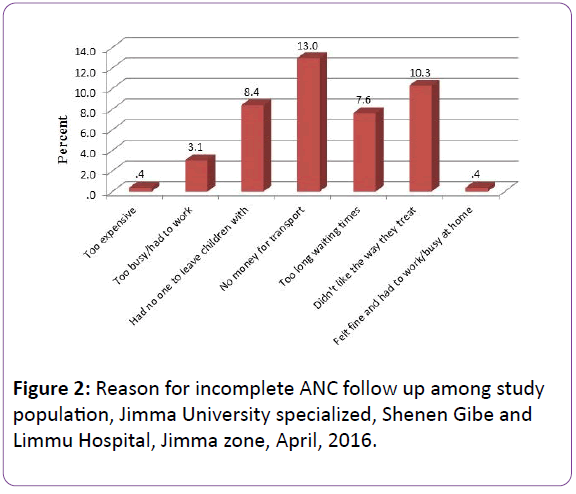

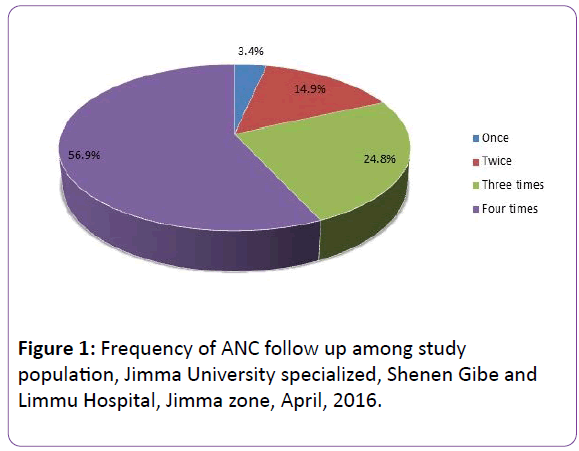

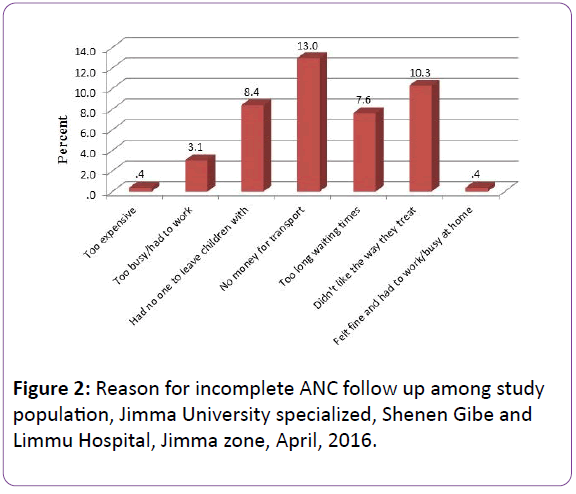

149 (56.9%) of all respondents had a complete ANC follow up. From 113 (43.1%) of respondents with incomplete ANC follow up, 34 (13%) and 27 (10.3%) of them were due to lack of money for transport and dislike the way they treated by health professions (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Frequency of ANC follow up among study population, Jimma University specialized, Shenen Gibe and Limmu Hospital, Jimma zone, April, 2016.

Figure 2: Reason for incomplete ANC follow up among study population, Jimma University specialized, Shenen Gibe and Limmu Hospital, Jimma zone, April, 2016.

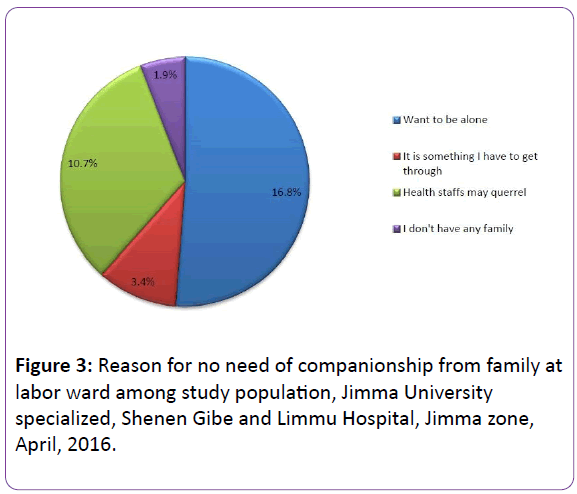

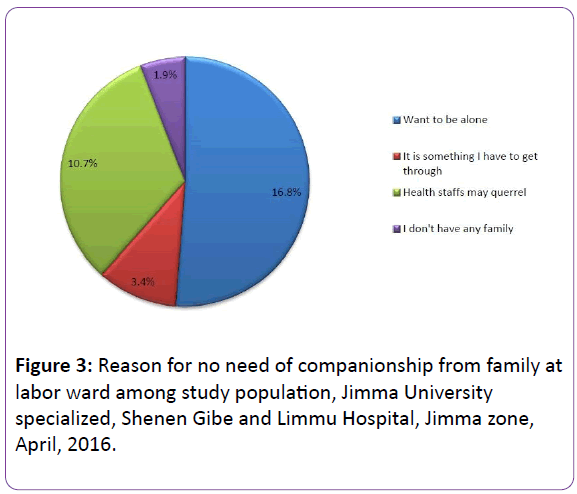

Need of companionship at labor ward

86 (32.6%) of respondents had no need of companionship from family at labor ward due to many reasons (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Reason for no need of companionship from family at labor ward among study population, Jimma University specialized, Shenen Gibe and Limmu Hospital, Jimma zone, April, 2016.

Postnatal check-up just after birth

235 (89.7%) of respondents had reported that they had postnatal check-up just after birth, and 29 (11.1%) of them had it as they was ill, and from those who hadn’t postnatal check-up just after birth, 14 (5.3%) of them were mentioned that because they were felt well/fine (Table 3).

| Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Postnatal check-up just after birth |

|

|

| Yes |

235 |

89.7 |

| No |

27 |

10.3 |

| Reason for postnatal check up |

|

|

| I was ill |

29 |

11.1 |

| Baby needed immunization/ill |

10 |

3.8 |

| Had told by midwife to do so |

18 |

6.9 |

| Wanted to know about family planning |

3 |

1.1 |

| Wanted to make sure as was back to normal |

16 |

6.1 |

| Don't remember |

6 |

2.3 |

| Baby needs immunization, I had told by midwife to do and I wanted to know about family planning |

19 |

7.3 |

| Baby needs immunization and told by midwife |

13 |

5 |

| Baby needs immunization and wanted to know about family planning |

19 |

7.3 |

| Baby needs immunization, told by midwife, want to know about family planning and to sure back to normal |

17 |

6.5 |

| Ill, told by midwife and make sure back to normal |

10 |

3.8 |

| Baby need immunization, told by midwife and make sure back to normal |

9 |

3.4 |

| Ill, baby needs immunization, told by midwife and wanted to know about family planning |

7 |

2.7 |

| Told by midwife and wanted to know about family planning |

8 |

3.1 |

| Baby needs immunization and wanted to sure as was back to normal |

5 |

1.9 |

| Was ill, baby needs immunization and to make sure back to normal |

2 |

0.8 |

| Told by midwife and wanted to sure back to normal |

30 |

11.5 |

| Was ill and wanted to sure back to normal |

14 |

5.3 |

| |

|

|

| Reason for no postnatal check up |

|

|

| Felt well/fine |

14 |

5.3 |

| No money for the service |

2 |

0.8 |

| Don't like the way health professions treat me there |

5 |

1.9 |

| No one to help and told to do so |

6 |

2.3 |

Table 3: Access to postnatal check-up just after birth of baby among study population, Jimma University specialized, Shenen Gibe and Limmu Hospital, Jimma zone, April, 2016. n=262.

Factors associated with provision of women friendly care

Bivariate and Multivariable logistic regression were used to identify the associated factors for provision of women friendly care. Coefficients were expressed as crude and adjusted odd ratios relative to the referent category and a number of factors were emerged to be significant for provision of women friendly care.

Discussion

Women friendly care is an approach to care giving with the goal of creating an enabling environment at all level to improve women’s access and utilization of safe motherhood and reproductive health services especially in settings where utilization is low [1].

This study was done on a randomly selected Jimma University specialized Hospital, Shenen Gibe Hospital and Limmu Hospital postnatal mothers with the history of ANC follow up and assessed the provision of women friendly care and associated factors to it. From the total respondents, 186 (71%) had provision of women friendly care at ANC, Delivery and Postnatal wards. This was less than the study conducted on Zambian women’s experiences of urban maternity care with the report of 89% of care as good care or women friendly care. The discrepancy might be due to the difference in study area, sample size and time of study [7].

The remaining 76 (29%) respondents reported as the care they had been receiving was not women friendly, and the care to be women friendly,13 (5%) of them recommended that care providers should be kind, not shout, with good attitude and care with no payment. This was supported with the study conducted in Malawi which stated that health workers’ attitudes are a great challenge in the provision of health care particularly during labor and delivery as deterred pregnant and laboring women from utilizing health services [10].

From all respondents, 53 (20.2%) of them were reported as they were treated badly, and from these 14 (5.3%) of them stated that they were shouted /scolded while receiving care. This was in line with the study conducted on Zambian women’s experience of urban maternity care in which 21% reported remembering someone who had treated them badly by shouting or scolding them during labor [7].

86 (32.6%) of respondents had no need of companionship from family at labor ward in which 10.7% of them were due to the fact that they worried of health staffs may quarrel on them and their companionship. This was supported by Cochrane database of systematic reviews on interventions for providers to promote a patient centered approach in clinical consultations, which declared that every woman must have the right to choose a companion to accompany her during labor and delivery [9].

Main means of transport showed statistically significant association with the respondents’ provision of women friendly care, that is those respondents who used public transport to reach health facility were four times more likely to get provision of women friendly care than those who used walk/on foot as the main means of transport to health facility (AOR=3.99, 95% CI [1.98, 8.05]). This was supported with the study report of Lari on health and quality of life outcomes, as the geographical accessibility of the health facility and the availability and efficiency of transportation affect women’s ability to access to health services and particularly speedy and easy access to health services is critical when it comes to the treatment of life threatening complications [11].

The other variable found to have a statistically significant association to provision of women friendly care was, being left alone in labor; that is respondents who left alone in labor were 59% less likely to get provision of women friendly care (AOR=0.41, 95% CI [0.19, 0.87]). This was consolidated by the study done by Kleeberg on patient satisfaction and quality of life, stating that, it is important to provide access to good quality care by trained and motivated personnel and not to leave them un attended to empower women to demand the services they need and tend to use the health services that satisfy their needs [6].

Women who treated badly were 94.6% less likely to demand for the provision of women friendly care (AOR=0.054, 95% CI [0.023, 0.13]). This was similar with USAID-report of exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility based child birth, which stated that, a woman’s relationship with health care providers and maternity care system during pregnancy and child birth is vitally important as women’s experiences with care givers at this time has the impact to inflict lasting damage and emotional trauma and stay with them for a life time and often shared with other women and detracting them from seeking maternity care [4].

A report of WHO/ UNICEF/UNFPA Workshop, on women friendly health service experiences in maternal care also supported this issue by stating that “women may refuse to seek care from a provider who “abuses” them or doesn’t treat them well, even if the provider is skilled in preventing and managing complications and the existence of clinically and administratively sound health care provision system doesn’t necessarily ensure the utilization of health care services if the mother is dissatisfied with the way care is provided [1].

Conclusion

Understanding of the provision of women friendly care and associated factors is paramount important for improving service utilization especially in settings where utilization is low and is part of a broader strategy to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and requires strong partnerships between governments, health systems and communities. This study has revealed that a substantial proportion of the mothers 186 (71%) were got a provision of women friendly care at ANC, Delivery and Postnatal. The care to be women friendly, 13 (5%) and 12 (4.6%) of them recommended that care providers should be kind, not shout, with good attitude, care with no payment & care providers should be kind, not shout, with good attitude, stay near, care with no payment and clean toilets and bathrooms respectively[12-14].

149 (56.9%) of all respondents had a complete ANC follow up. From all respondents, 67 (25.6%) and 56 (21.4%) were assisted with the delivery of baby by Doctor and Doctor, nurse and midwifery students and midwife and nurses respectively. 235 (89.7%) of respondents had reported that they had postnatal check-up just after birth. Variables like Main means of transport, being left alone in labor, and being treated badly were all significantly associated with provision of women friendly care at both crude and adjusted odd ratios at p<0.05.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

Both authors participated in the design and analysis of the study. BF searched the databases, and wrote the first and second draft of the article. TG reviewed proposal development activities and each drafts of the result article. Both authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

First and for most we would like to thank the almighty God for initiating us for doing this research thesis on such a burning issue of women friendly care .

Then we extend our thanks for Ethio-Canada MNCH project and Micro-Research initiatives for supporting us to conduct this research thesis.

Lastly, but not least our heartfelt thanks goes for all who helped us throughout this thesis work including Ethio-Canada MNCH project staffs, health care managers, service providers of study areas and respondents.

20185

References

- Women friendly Health services Experiences in maternal care: report of a WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA workshop (2008) Mexico City.

- Maggie Kempon (2009) Defining and implementing mother friendly Health Services .A low cost initiative to address Maternal mortality in Papua New Guniea.

- How to make maternal health services more women friendly, a practical guide, Lusaka Women-friendly Services Project, 2009.

- Bowser D, Hill K (2010) Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in facility based child birth: Report of Landscape Analysis. Bethesda, MD: USAID-TRAction Project, University Research Corporation, LLC, and Harvard School of Public Health.

- Hospital EC, Changole J, Bandawe C, Taulo F (2010) Patient’s satisfaction with reproductive health services at Gogo Chatinkha Maternity Unit. Queen 22: 5-9.

- Kleeberg UR, Tews JT, Ruprecht T, Hoing M, Kuhlmann A, et al. (2005) Patient satisfaction and quality of life in cancer out patients:resultsof the PASQOC* study. Support Care Cancer 13: 303-310.

- MacKeith N, Chinganya OJ, Ahmed Y, Murray SF (2008) Zambian Women’s experiences of urban maternity care: results from a community survey in Lusaka. African Journal of Reproductive Health 7: 92-102.

- Lule GS, Tugumisirize J, Ndekha M (2006) Quality of care and its effects on utilization of maternity services at health centre level. East African Medical Journal 77: 250-255

- Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J (2005) Interventions for providers to promote a patient centred approach in clinical consultations. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

- Kumbani LC, Chirwa E, Malata A, Odland JO, Bjune G (2012) Do Malawian women critically assess the quality of care ? A qualitative study on women’ s perceptions of perinatal care at a district hospital in Malawi 2: 1-14.

- Lari A, Tambulin M, Gray D (2004) Patients’ needs, satisfaction,and health related quality of life: Towards a comprehensive model. Health and Quality of Life outcomes 2: 32.

- Respect full Maternity care: The universal rights of Childbearing Women (2007) white Ribbon Alliance, One Thomas circle, NW, Suite200, Washington DC.

- Improving maternity services utilization in Ethiopia by providing culturally sensitive and women friendly care (2011).

- Lochoro P (2007) Measuring patient satisfaction in UCMB health institutions. Health Policy and Development 2: 243-246.