Review Article - (2023) Volume 10, Issue 4

Assessment of the Legal Framework and Participant Perceptions on Organ Donation in Tshwane, South Africa

Bongani Ndhlovu*

Department of Immunology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

*Correspondence:

Bongani Ndhlovu, Department of Immunology, University of Pretoria,

Pretoria,

South Africa,

Tel: 0848874133,

Email:

Received: 23-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. IPHSPR-23-13513;

Editor assigned: 27-Feb-2023, Pre QC No. IPHSPR-23-13513 (PQ);

Reviewed: 14-Mar-2023, QC No. IPHSPR-23-13513;

Revised: 05-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. IPHSPR-23-13513 (R);

Published:

12-Apr-2023

Abstract

Background: To review the legal framework governing organ donation and to get insight into the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of participants on organ donation at Eersterust Community Health Centre (ECHC).

Methods: A desktop literature review with the aid of a legal expert and a cross sectional, descriptive study was conducted. The study population comprised of adult patients who consulted at ECHC. Data collected using a validated structured interview schedule. Socio-demographic factors associated with a positive or negative attitude towards organ donation were evaluated. Data were analysed by means of logistic regression in stata version 14.

Results: A total of 123 people were interviewed. A large proportion (50/123–40.7%) had never heard of organ donation. Of 73 (59.3%) participants were aware of organ donation, 70 (95.89%) said organ donation should be encouraged, 39 (53.42%) said an ‘opt-out’ (presumed consent) law would encourage people to donate organs, and 46 (63.02%) had a positive attitude towards the introduction of an ‘opt-out’ law. There was a significant association between both the level of education and occupation, and having a positive attitude towards the introduction of an ‘opt-out’ law. The South African (SA) health system currently follows the ‘opt-in’ organ procurement method, which differs from countries with higher organ donation rates.

Conclusion: The opt-in organ procurement system in SA sets the donation status as ‘refusal to donate’. Participants demonstrated a positive attitude towards organ donation and the introduction of an ‘opt-out’ law on organ donation.

Recommendations: There is a need for increasing awareness about organ donation. A larger study should be conducted to get a more holistic perspective on a larger range of participants.

Keywords

Organ donation; Opt-out law; South Africa;

Eersterust Community Health Centre (ECHC); Organ donor

foundation

Abbrevations

ECHC: Eersterust Community Health Centre;

IQR: Interquartile Range; SA: South Africa; SAMJ: South

African Medical Journal; SADoH: South African Department

of Health; SANDPP: South African National Director of Public

Prosecution; UNOS: United Network for Organ Sharing; UK:

United Kingdom; WHO: World Health Organization

Abbrevations

ECHC: Eersterust Community Health Centre;

IQR: Interquartile Range; SA: South Africa; SAMJ: South

African Medical Journal; SADoH: South African Department

of Health; SANDPP: South African National Director of Public

Prosecution; UNOS: United Network for Organ Sharing; UK:

United Kingdom; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

Background

The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996

(Constitution) guarantees the right to access healthcare for all,

but a considerable number of patients, especially in rural areas

of SA are not able to access dialysis or other specialized medical

care [1]. SA is faced with an increasing shortage of organs and

tissues available for transplantation and there are in excess of

4500 patients currently awaiting organ and tissue transplants,

and over 2000 estimated patients waiting for life saving organ

transplants at any given time in SA. The number of transplants

performed in SA, however, has not amounted to 400 in the past

seven years (2004-2011). There is no national waiting list for

patients in need of transplantation in SA.

Organ donation is recognized globally as the most cost

effective therapeutic measure for patients with end stage organ

failure. Even though anti-rejection therapy is still considerably

expensive, it remains less costly than treatment associated with

serious injuries, cancer and myocardial infarction, which are also

prevalent in SA.

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) is an American

organization which has been coordinating the procurement and

transplantation of organs in the United States since 1986. UNOS

maintains a computerised system which monitors the status of

thousands of potential recipients, which allows for minute by

minute changes in the status of the patient. The Organ Donor

Foundation (ODF) is a non-profit organization in SA tasked with

public education and awareness on organ donations. The ODF is

however not involved in the procurement of organs and

transplantations.

In instances where the donor is deceased, the donor must

first be declared brain dead prior to being eligible to donate an

organ. The national health act defines death as brain death.

Brain death can be due to head trauma, cerebral haemorrhage

due to a stroke or aneurysm, brain tumour and anoxic injuries.

All these physiological events can cause swelling and ultimately

cut off all blood flowing to the brain, leading to an infarct.

Cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes mellitus (diabetes),

cancer and chronic lung disease are at epidemic proportions in

the developing world and SA is experiencing a similar trend in

the prevalence of these chronic conditions. The World Health

Organization (WHO) estimates that non-communicable diseases

have a two to three fold higher impact on SA, compared to

developed countries. The need for kidney transplants is the

greatest and chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension

and HIV/AIDS continue to add to the increasing numbers of

patients with renal failure. It can thus be projected that the need

for renal transplantations will also continue to increase [2].

There has, however, been a substantial decline in the number of

organ transplants performed annually in SA and it is worth

noting is that there has been a decline in the rate of consent for

organ donation among families of brain dead potential donors

(55% in 1991, 50% in 2001 and 32% in 2011).

The primary reason behind the critically low organ transplant

rates in SA is the low numbers of available organs. So, while the

demand for organs remains high and continues to grow, the

supply has been stagnant and is most likely declining.

Interestingly however, a February 2014 paper in the South

African Medical Journal (SAMJ) confirmed data from an earlier

study (1987-1990) which revealed that attitudes of the SA urban

black and white population were positive towards the donation

of organs.

There is, however, limited information or no information at all

concerning the attitudes of people in SA, concerning organ

donations.

The first aim of this study was to investigate the legislative

framework governing organ donation in SA. The second aim of

the study was to get insight into the knowledge, attitudes and

perceptions of participants in Tshwane district regarding organ

donation, as well as to determine whether they would be ready

to embrace an ‘opt-out’ policy on organ donation.

Literature Review

A review of the South African legal framework governing organ donation

Introduction: Organ transplantation is a well-recognized life saving intervention for life threatening conditions involving end stage organ failure. Organ transplantation is globally accepted as an essential specialist medical service.

For organ transplantation to be a success, there are different components of the healthcare system that need to be in place, and be effectively and efficiently functional. These include sufficiently trained health workers, specialist high care facilities, sufficient medication, laboratory and other diagnostic facilities, referral systems, appropriate governance, as well as (most importantly) members of the public who are sufficiently educated on organ donation and are willing to become donors.

Section 27 in chapter 2 of the constitution of the republic of SA, 1996, guarantees the right to have access to healthcare services for all. Regrettably, despite this guarantee, a significant number of patients in SA, particularly in rural settings, are unable to access dialysis or other specialized healthcare services. Such specialized medical care is necessary to sustain life until an appropriate transplantation organ can be sourced. As a consequence, patients suffering from end stage organ failure die prior to being listed on the organ transplant waiting list [3]. What is more concerning is that even when on the waiting list, very few patients are successfully matched to a donated organ.

Little is known in the medical field about how the SA legislative system aids or deters organ donation. In order to address this gap, a desktop review was conducted on this topic.

Methods: A desktop literature review was conducted with the guidance of a legal expert. The legislation, common law and case law were examined, and contrasted with examples from other countries.

Results: Organ donation rests on the ethical and legal principle of respect for individual autonomy through obtaining voluntary consent. There are two main ways in which it can be determined that voluntary consent had been obtained:

• The “opt-in” approach which assumes that only those persons who have given explicit consent are organ donors; and

• The “opt-out” approach that states that anyone who has not refused consent to donate is a donor.

Little is known in the medical field about the way in which the SA legal system aids or deters organ donation. Improved understanding is imperative if healthcare workers are to develop a better understanding of the legal framework within which organ donation can be encouraged.

The SA health care system follows an opt-in procurement method. Unfortunately, currently not enough organs are procured in this manner to sufficiently meet the demand for organs. The shortage of organs is a global phenomenon and, thus, no procurement system currently in place anywhere has able to meet the demand for organs.

In the opt-in system used in SA, a potential donor indicates a willingness to donate an organ voluntarily by registering with the ODF, and they also need to inform their next-of-kin of their wish to donate an organ. In SA, the consent of the donor’s next of kin is requested, out of courtesy, prior to the harvesting of organs, even in cases where the donor has already opted-in. As a consequence, it is said that the “most significant aspect of this method of procuring transplant organs is its clear failure to secure anywhere near the number of organs that are required”. Registration with the ODF is essentially only for statistical purposes as the register is not checked prior to organ donation.

According to the ODF, 342 solid organ transplants were performed in SA in 2010 and of these, 63% were performed in private hospitals, on privately funded patients. Figures from the ODF for 2015 indicate that there were about 4300 South Africans awaiting life saving organ transplants. This number is on the rise, while the number of available donor organs remained unchanged. Whenever the demand for a particular resource is greater than the supply, a risk arises of the emergence of a black market to compensate for the deficit. The facts that gave rise to the case of Sv Netcare Kwa-Zulu (Pty) Ltd 41/1804/2010* underscore the nature and extent of the organ donation black market in SA and globally.

The national health act, 61 of 2003 came into effect on 2 May 2005. The act stipulates in section 62 that anyone competent to make a will may donate an organ by signing a document or by indicating a wish to donate through a clause in a will. This is done while the donor is still alive and of sound mind, in other words, while they are compos mentis.

Netcare Kwa-Zulu (Pty) Ltd entered into an agreement in November 2010, under the authority of the South African National Director of Public Prosecution (SANDPP), by pleading guilty to 102 counts related to charges arising from having allowed its employees and facilities to be used to conduct illegal kidney transplant operations which took place between June 2001 and November 2003. Israeli citizens who were in need of kidney transplants were brought to SA for transplants performed at Netcare St Augustine’s hospital, Berea and Durban. Kidneys supplied were initially sourced from Israeli citizens but later Brazilian and Romanian citizens were recruited as their kidneys were much cheaper.

Section 65 of the act allows the donor to revoke his or her decision to donate an organ prior to the transplantation of the relevant organ into the recipient. In the absence of a will made by the deceased before death, section 62 (2) of the national health act stipulates that the deceased’s spouse, major child, parent, guardian or major sibling may grant permission for the donation of usable organs after death. In practice, a family member is consulted for consent in almost every case, regardless of whether or not the deceased had indicated his or/her wish to become an organ donor. This is a global practice and there seems to be no legal basis for it.

It is most probably done out of courtesy and respect for the deceased’s family. This allows the next of kin’s input into the donation process to be considered, especially in instances where donation could potentially cause undue suffering to the deceased’s relatives. This ‘soft’ application of the opt-in law (in contrast to the ‘hard’ alternative where relatives would not be consulted prior to harvesting of organs) has been shown to work well in European countries. Section 62 (3) (a) of the national health act allows the director general of the SA.

Department of health (SADoH) to approve the donation of the deceased’s organs after all reasonable steps and attempts have been exhausted to locate the relevant family members.

The national health act further defines death as “brain death”. Section 60 (4) (a) of the Act makes it an offence for a person who donated an organ or tissue to receive any form of financial or other reward for such a donation.

Section 8 of the SA constitution, 1996, states that the rights in the bill of rights are applicable to all law, and are binding on the legislature, the executive, the judiciary and all organs of state in all spheres of government. All these entities and persons, therefore, have to comply with the bill of rights. Also, according to section 172 (1) of the constitution, any legislation that does not comply with the Bill of Rights is invalid to the extent of its conflict with the bill of rights.

When considering the current opt-in method on organ procurement in SA, the rights of individuals in terms of the bill of rights to have access to health care services and therefore to an adequate supply of organs, has to be enforceable against the state who has to progressively realize the right to access health care services or, in this situation, a sufficient and suitable supply of organs. In other words, it has to be determined whether the state has complied with its responsibilities and duties in terms of section 27, where it is given the duty to ensure access to health care services for all.

It must, however, be remembered that the rights in the constitution are not absolute and that they may be limited (in terms of section 36 of the constitution). Such a limitation of rights may be done only if it is reasonable and justifiable in an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom (in terms of section 36 (1) of the constitution, 1996).

SA is a multi-cultural country with people from various beliefs, backgrounds, cultures and religions. Legislation regulating methods of organ procurement (such as chapter 8 of the national health act 61 of 2003) has to accommodate the various religions and cultures without unreasonably limiting the rights of others or placing a burden on them.

The current legislation in SA sets the default position as ‘refusal to donate’ or non-donation. In contrast to this opt-in approach, an opt-out (presumed consent) system allows people to state and register their unwillingness to donate their organs after death. In cases where there is no recorded opt-out, the default (presumed) position would be that they wish to donate their organs.

Legislation on its own should not be regarded as a remedy for the shortage of available transplant organs. Nevertheless, a legislative environment that promotes donation plays an important role in facilitating the number of organs available for donation. Spain, for example, has the highest donation rate in the world with 34 donors per million of the population and in that country the legislative framework creates an opt-out system of donation.

The United Kingdom (UK), by contrast, currently uses an opt-in law (but Wales uses the opt- out system) and has a low donation rate (14 donors per million of the population) compared to 23 in France, 27 in Belgium 9 and 34 in Spain. The most significant factors responsible for low organ donation in the UK include the shortage of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds, a failure to identify potential donors in ICU, a failure to perform brain stem death tests, and a refusal by relatives to allow organ donation to be carried out. These factors, including a lack of knowledge and widely held false beliefs regarding organ donation, are also likely to be contributing to SA’s low donation rates.

The opt-out system in Spain is only part of the reason for the country’s success. Other factors include the expansion of organ transplant coordinator teams, a routine referral system, better availability of ICU beds and a high rate of motor vehicle accidents, the latter of which is probably even higher in SA.

In the opt-out system, the presumption of consent does not imply that the potential donor has in fact consented to donate organs and, thus, the role of the donor’s family remains crucial. Opt-out legislation can be effective only if there is a sympathetic and trusting relationship between the family and the transplant coordination team.

A breakdown of this relationship could lead to negative publicity and an increase in people opting out of organ donation.

Public awareness regarding the benefits of the proposed opt-out legal system is essential. There is strong evidence suggesting that a good educational framework, over time, would reduce opting-out and family refusal, resulting in organ donation becoming a normative preference [4]. This is evidenced by the fact that the majority of UK citizens (64%), despite a low donation rate, are in favour of the opt-out system being introduced in the UK. The UK’s Prime Minister announced on the 4th October 2017 that the UK will adopt the opt-out system following a two year campaign run by the Daily Mirror newspaper, which has been hailed by health campaigners, medics, members of parliament and patients.

Conclusion: The state is mandated by the constitution to create policies which promote health for all by allowing citizens and non-citizens to access health services. The current opt-in legislative system on organ donation used in SA does not encourage organ donation. In people who have explicitly opted-in, their autonomy with regard to the disposition of their organs needs to be protected by a legislative framework which will do away with the practice of seeking additional consent from family members prior to harvesting of organs. Instead, recommend that the deceased’s next of kin should rather be politely informed of the deceased’s wishes and the legal mandate bestowed upon the state to dispose of their organs.

Methodology

Donation of organs is a globally recognised life saving

intervention which can potentially save up to eight lives. In SA

however, only 0.3% of the population is registered as donors

with the ODF. The ODF is a non-profit organisation established

29 years ago to address the severe shortage of organ donors in

SA. The ODF in 2014 had 120 000 registered organ donors on its

database, 66% of whom were females with KwaZulu-Natal accounting for only 10% compared to Gauteng’s 45%. This

study seeks to assess participant’s perceptions on organ

donation.

Methods

Study design and area: This was a cross-sectional, descriptive

study conducted at ECHC in Tshwane, SA. This clinic is located in

a residential area is in the east of Pretoria, in the Tshwane local

municipality in Gauteng province. This study was conducted at

the ECHC oral health clinic which renders basic oral health

services to over 400 patients monthly and around 35 patients

per day.

Study population and sampling: The study population

comprised of patients consulting at the oral health department

at ECHC between October 2016 and March 2017. Patients above

the age of 18 years were randomly selected to participate in the

study through a process of systematic sampling, i.e. every third

patient. A total of 123 interviews were conducted. The sample

size was determined using the norm of 15 participants per

variable. Seven variables of interest were explored. I estimated

that approximately 18% of participants would not have heard

about organ donation and therefore elected to interview a

minimum of 120 participants.

Data collection tool: An existing, validated structured

interview schedule (Appendix) from a 2009 Pakistani study on

organ donation using the Knowledge, Attitude and Practices

(KAP) approach by Saleem Taimur, et al., was adapted to have

local significance (the wording on question 14, 15, 27 and 32

was amended). The questionnaire was pilot tested in 5

participants to assess whether questions were understood with

ease and yielded expected responses. These 5 pilot

questionnaires were not included in the data analysis. No

further changes were made to the questionnaire after the pilot

phase.

The study is quantitative. Age, gender, religious affiliation,

level of education/literacy, level of knowledge on organ

donation were evaluated.

An in-depth interview was employed to collect data. This form

of interview was a discussion between the interviewer and

interviewee on organ donation. The interview was directed

using the questionnaire so as to collect the required data, but

respondents were allowed to talk and cover the topic from their

own perspective.

Since no participants had heard about the opt-out law on

organ donation before, they were told about what the law

entails.

The study was primarily quantitative. Information about

socio-demographic variables, such as age, gender, religious

affiliation and level of education/literacy, were collected, and

participants’ level of knowledge about organ donation, as well

as their attitudes and support for an opt-out practice, were

evaluated.

Statistical analysis: Data collected using the questionnaires

were analyzed using Stata. Basic descriptive analysis was done

by means of t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square testing of categorical variables. If data were not normally

distributed, non-parametric equivalents were used, i.e. Kruskal-Wallis and Fisher exact tests. Logistic regression was used to

assess associations between variables and participants

knowledge and attitudes about organ donation.

Some variables, such as religion, age and occupation, were

divided into categories, according to the literature or the

distribution of the data. The vast majority of participants were

Christian and there were only a few participants who were

either Muslim or did not belong to a religion or were atheist.

Religion was thus classi ied into two main categories for the

purpose of statistical analysis, i.e. Christianity and other.

Age was categorized into three groups, in accordance with a

similar previous study. There were eight occupation categories

(Table 1). For the purpose of statistical analysis, occupation was

categorized into three groups, i.e. government employees, non-governmental

employees and unemployed people. Education

consisted of ive levels and was divided into a binary category:

No versus any university quali ication.

Composite variables were created for knowledge, attitude,

support for an opt-out practice, and an overall category by

combining the following questions in the questionnaire.

*Knowledge (about organ donation): Questions 7, 8, 10, 11

and 12. The maximum possible score was 5 and participants

were seen to have good knowledge if they scored equal to or

above 2 out of 5 and were deemed to have poor knowledge if

they scored below 2.

Individual questions were scored as follows:

Question 7: 1=1 2=0 3=0

Question 8: 3=1 1=0.5 2=0.5 4=0 5=0

Question 10: 1=1 2=0.5

Question 11: q11=1 if q11g==1, q11=0 if q11hi==1

Question 12: 1=1 2=0 3=0

Attitude (towards organ donation): Questions 16,17,19 and

25 were used to generate composite score for attitude. The

maximum possible score was 4 and participants were seen to

have a positive attitude if they scored equal to or above 2 out of

5 and were deemed to have poor knowledge if they scored

below 2. Individual questions were scored as follows:

Question 16: 4=1 2=0.5 3=0.5 1=0

Question 17: 1=1 2=0 3=0

Question 19: 1=1 2=0 3=0 4=0 5=0

Question 25: 1=1 2=0 3=0

Support (for opt-out testing): Questions 30, 31 and 32 were

used to create opt-out composite variable. The maximum

possible score was 3 and participants were seen to be in support

of opt-out testing if they scored equal to or above 0.5 out of 3,

and were deemed to have poor knowledge if they scored below

0.5. Individual questions were scored as follows:

Question 30: 1=1 2=0 3=0

Question 31: 1=1 2=0 3=0

Question 32: 1=1 3=0.5 2=0 4=0

*An overall score was determined by combining the above

three composite variables, i.e. overcomp=kcomp+acomp+oocomp. The maximum score was 10 and participants were

given a positive overall score at values equal to or above the

median (6.5).

Results

Socio-demographic variables are shown in Table 1. There was

a total of 123 respondents (no person refused to be interviewed)

with a median age of 40 years and an Interquartile Range (IQR)

of 30-56. Females constituted the majority of study

participants–78 (63.4%) while there were only 45 males (36.6%)

(Table 1). Sixty respondents were coloured, 44 black, 14 white

and 5 were of Indian descent. The vast majority of study

participants were Christians (85.4%), followed by Islam (4.9%),

atheism (3.4%), Hinduism (1.6%) and other (5.7%). The majority

(48%) of study participants had completed secondary school

education, 8.9% completed only primary school, 37.5% had an

undergraduate qualification, 4.1% a post-graduate qualification

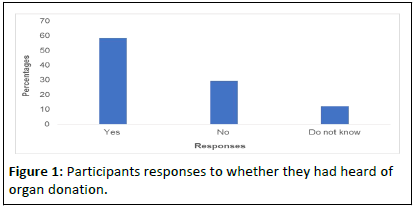

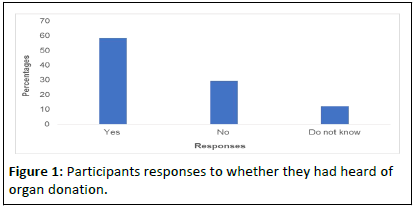

and only 1.6% were illiterate of the total of 123 respondents, 73

(59.3%) had heard about organ donation, while 35 (28.5%) had

not and 15 (12.2%) did not know whether or not they had heard

about it.

The group who had never heard of organ donation had the

following characteristics that are also depicted in Table 1. There

was a total of 50 (out of 123) respondents. Females constituted

64% of the group. The racial composition of this group was: 42%

blacks, 6% whites, 50% coloured and 2% of Indian descent. The

18–34, 35–54 and 55+ years old age group made up 38%, 34 and

28% of the group respectively.

A large proportion (32%) of participants in this group was not

employed and the highest education level achieved by most

(68%) was high school.

A large proportion of participants (40%) were married and

92% of participants identified themselves as Christians.

Participants who had never heard about organ donation

differed significantly from those who had prior knowledge in

terms of level of education and occupation. Participants who

had never heard of organ donation were more likely to be black

(race), older (55+ years old), not employed, have secondary

school education as highest qualification and be Christian

(especially since Christianity was the dominant religion in this

cohort).

Interviews were only continued in the 73 (59%) respondents

who had heard about organ donation (Figure 1). Among the 73

who had heard about organ donation, 46 (63.1%) were females,

35 (47.9%) were coloured, 28 (38.4%) were in the 18-34 years

old age group, 38 (52.1%) had an undergraduate education

qualification, and 58 (79.5%) were Christians (Table 1).

Figure 1: Participants responses to whether they had heard of organ donation.

| Characteristics |

N (%) (Total=123) |

Participants who had never heard of organ donation n (%) (Total=50) |

Participants who had heard of organ donation n (%) (Total=73) |

p-values* |

| Race |

0.2 |

| Black |

44 (35.8) |

21 (42) |

23 (31.5) |

|

| White |

14 (11.4) |

3 (6) |

11 (15.1) |

|

| Coloured |

60 (48.7) |

25 (50) |

35 (47.9) |

|

| Indians |

5 (4.1) |

1 (2) |

4 (5.5) |

|

| Sex |

0.9 |

| Male |

45 (36.6) |

18 (36) |

27 (36.9) |

|

| Female |

78 (63.4) |

32 (64) |

46 (63.1) |

|

| Age in years |

0.9 |

| 18-34 |

46 (37.4) |

19 (38) |

28 (38.4) |

|

| 35-54 |

46 (37.4) |

17 (34) |

28 (38.4) |

|

| ≥ 55 |

31 (25.2) |

14 (28) |

17 (23.3) |

|

| Occupation |

<0.001 |

| Student |

5 (4.1) |

4 (8) |

1 (1.37) |

|

| Government employee |

25 (20.3) |

7 (14) |

21 (28.8) |

|

| Non-government employee |

35 (28.4) |

8 (16) |

24 (32.9) |

|

| Housewife |

5 (4.1) |

1 (2) |

4 (5.4) |

|

| Self employed |

9 (7.3) |

1 (2) |

8 (10.9) |

|

| Volunteer |

3 (2.4) |

1 (2) |

2 (2.7) |

|

| Retired |

21 (17.1) |

12 (24) |

9 (12.3) |

|

| Not employed |

20 (16.3) |

16 (32) |

4 (5.4) |

|

| Education level |

<0.001 |

| Primary school completed |

11 (8.9) |

9 (18) |

4 (5.5) |

|

| Secondary school completed |

59 (47.9) |

34 (68) |

26 (35.6) |

|

| Undergraduate qualification |

46 (37.5) |

5 (10) |

38 (52.1) |

|

| Post-graduate qualification |

5 (4.1) |

1 (2) |

4 (5.5) |

|

| Illiterate |

2 (1.6) |

1 (2) |

1 (1.4) |

|

| Marital status |

0.9 |

| Never married |

41 (33.3) |

18 (36) |

23 (31.5) |

|

| Married |

57 (46.3) |

20 (40) |

36 (49.3) |

|

| Engaged to be married |

13 (10.7) |

3 (6) |

0 (0) |

|

| Divorced |

12 (9.7) |

9 (18) |

14 (19.1) |

|

| Religion |

0.1 |

| Islam |

6 (4.9) |

0 (0) |

9 (12.3) |

|

| Christianity |

105 (85.4) |

46 (92) |

58 (79.5) |

|

| Hinduism |

2 (1.6) |

1 (2) |

0 (0.0) |

|

| Atheist |

3 (2.4) |

1 (2) |

6 (8.2) |

|

| Other |

7 (5.7) |

2 (4) |

0 (0.0) |

|

| *Comparison between participants who had heard and those who had not heard about organ donation before |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of study participants.

Participants’ knowledge and attitudes related to organ

donation are shown in Table 2. To assess participant’s

knowledge about what ‘organ donation’ means, five different

responses were available for participants to choose from. Two

participants defined organ donation as ‘tissue removal from a

deceased human body’. Three participants defined the term as

‘tissue removal from a living human body’, 27 participants

regarded the term as removing human tissues for

transplantation to another person.

Forty participants defined organ donation as a combination of

all the above- mentioned options, while only one defined it as

‘other’.

To assess participants views on the purpose of organ

donation, 97.3% of respondents regarded organ donation as an

act of saving a life, while the remainder offered different

reasons [5]. One respondent’s reason for considering donating

his organs a ter death was that he would somehow continue to

live through another person and it would make him content that

his organ would not go to waste.

| Response |

n (%) |

| Have you ever heard of organ donation? |

| Yes |

73 (59.3) |

| No |

35 (28.5) |

| Do not know |

15 (12.2) |

| What is organ donation? |

| Tissue removal from dead human body |

2 (2.7) |

| Tissue removal from living human body |

3 (4.1) |

| Tissue removal to be transplanted to another person |

27 (37) |

| All of the above |

40 (54.8) |

| Other response |

1 (1.4) |

| Why is organ donation done? |

| To save a life |

71 (97.3) |

| Other reasons |

2 (2.7) |

| Are you aware of the ODF in SA? |

| Yes |

27 (37) |

| No |

46 (63) |

| Would you consider donating an organ? |

| Never |

6 (8.2) |

| Yes |

44 (60.3) |

| Only under special circumstances |

20 (27.4) |

| I would regardless of circumstances |

3 (4.1) |

| Does your religion allow organ donation? |

| Yes |

15 (20.6) |

| No |

3 (4.1) |

| I don’t know |

55 (75.3) |

| Is there a danger that donated organs could be misused? |

| Never |

13 (17.8) |

| Sometimes |

58 (79.5) |

| Often |

2 (2.7) |

| Should organ donation be encouraged? |

| Yes |

70 (95.9) |

| No |

1 (1.4) |

| I don’t know |

2 (2.7) |

Table 2: Knowledge of the study participants pertaining to organ donation (N=73).

An encouraging proportion of study participants (60.3%)

would consider donating an organ, while 8.2% said they would

never consider donating an organ. A significant number (27.4%)

were willing to only donate under ‘special circumstances’, the

most common being donating to a blood relative such as a

sibling, parent or child. Some respondents (4.1%) were willing to

donate organs regardless of the circumstances.

A very low number of participants (37%) knew about the ODF

in SA. While the majority (91.9%) of participants in this study

belonged to a religion, 55 (75.3%) did not know whether their

religion allows them to become organ donors. Participants who

responded that their religion allows/encourages organ donation

(20.6%), validated their response with the statement that “the

Bible encourages them to do good unto others”.

A large number of respondents (80.6%) believed that donated

organs could be misused. A concern which stood out was that

the misuse could actually constitute the sale of organs on the

black market, where those with financial wherewithal would be

at an advantage to receive organs (through purchasing) compared to the poor, especially considering the highly unequal

income distribution in SA.

However, another positive outcome from this study was that

almost all participants (95.9%) thought that organ donation

should be encouraged in SA, with most participants stating that

it is a public good deed.

Participant’s attitudes towards an opt-out law were also

assessed and the results are presented in Table 3. When asked

whether an opt-out law on organ donation would encourage

organ donation in SA, 53.4% of participants thought an opt-out

law would make a significant contribution towards growing the

number of organ donors.

Only 8.2% of participants did not think that the law would

encourage organ donation, while the remainder did not have an

opinion. It should be noted that that none of the participants

had prior knowledge about an opt-out law on organ donation.

| Characteristics |

n (%) |

| Would opt-out law encourage organ donation? |

| Yes |

39 (53.4) |

| No |

6 (8.2) |

| I don’t know |

28 (38.4) |

| Would it be just to disqualify those who opt-out from receiving organs? |

| Yes |

17 (23.3) |

| No |

14 (19.2) |

| I don’t know |

42 (57.5) |

| Should the opt-out law be introduced in SA? |

| Yes |

28 (38.3) |

| No |

5 (6.9) |

| Maybe |

18 (24.7) |

| I don’t know |

22 (30.1) |

Table 3: Participants attitudes towards opt-out law (n=73).

Seventeen participants shared the sentiment that it would be

fair to disqualify people who choose not to donate their organs

from receiving organs should they require organ transplantation

in the future. Most of these participants felt that it is not fair to

receive organs while not willing to donate.

However, 14 participants felt it would not be fair to disqualify

those who opt not to donate. One respondent mentioned that

disqualifying people would not be in harmony with the

sentiments of the constitution of the republic of SA, which

espouses freedom of choice without discrimination and hindrance of autonomy. The remainder of participants did not

know whether it would be fair or not.

The majority of respondents (38.3%) said that the opt-out law

should be introduced in SA, while only 6.9% disagreed, and

24.7% were undecided, but leaning towards the introduction of

the law.

Further analysis was conducted to assess the association

between socio-economic variables and participant’s knowledge,

attitude and support of an opt-out policy (Table 4). No

associations were found between age, religion, race or marital race or marital status and participants knowledge, attitude and

support for an opt-out system, as well as a combined category, surrounding organ donation.

| Variable |

Knowledge |

Attitude |

Opt-out |

Overallǂ |

| Age |

0.692 |

0.135 |

0.179 |

0.552 |

| Religion |

0.864 |

0.203 |

0.933 |

0.397 |

| Education level |

0.345 |

0.704 |

0.001 |

0.024 |

| Occupation |

0.255 |

0.768 |

0.044 |

0.63 |

| Race |

0.888 |

0.158 |

0.413 |

0.709 |

| Marriage |

0.556 |

0.25 |

0.496 |

0.668 |

| Statistically significant, ǂcomposite outcome variable |

Table 4: Associations between predictor variables and knowledge, attitude, support of opt-out policy and a composite outcome variable.

There was a statistical significant association between the

level of education and having a positive attitude towards the

opt-out policy on organ donation. Participants with higher

levels of education (i.e. completed secondary education and

beyond) were more likely to be in support of an opt-out policy.

There was also a statistical significant association between

occupation and having a positive attitude towards the

introduction of an opt-out policy. Participants who were

employed were more likely to have a positive attitude. The level

of education was also significantly associated with an overall

positive score regarding organ donation, with better

educated participants most likely to display an overall

positive attitude.

Since the level of education was such an important predictor,

it was also assessed to determine whether any significant

associations with other variables existed. Table 5 shows a

significant relationship between the level of education and

occupation (p<0.001, i.e. being occupied is associated with a

higher level of education), race (p=0.017) and religion (p=0.019).

The level of education is associated with both belonging to a

religion (both Christianity and other) and all race categories

(1,2,3 and 4). The relationship between education and these

variables is not due to random chance, i.e. there was a

reliable association between education and races, occupations

and religion. However, there was no significant association

between the level of education and marital status.

| Variable |

Education level |

| Race |

0.017 |

| Religion |

0.019 |

| Marital status |

0.784 |

| Occupation |

0 |

| Statistically significant |

Table 5: Association between demographic variables and the level of education.

Discussion

In this study of the knowledge, attitudes and practices of

patients seen at an oral health clinic at ECHC, it was concerning

that 41% of the study population had not previously heard

about organ donation. This is especially worrisome since

participants were sourced from an urban setting, where

education levels are higher and access to information is better

than in rural settings. This presents an opportunity to

stakeholders to have public awareness an information

dissemination campaigns. The majority (54%) of those who had previously heard about organ donation had the most accurate

idea of what organ donation was.

Almost all respondents (97%) who had prior knowledge about

organ donation, regarded it as a life saving act, even though only

21% of participants thought their religion allows them to donate

organs. Perhaps religious organisations should be involved in the

clarification of the their standpoint on this issue, especially

considering that South Africans are largely religious and a

significant number of people are probably guided by religion

when making decisions concerning death and the ‘after life’.

The high number (97.3%) of participants who regarded organ

donation as a life saving act was in agreement with the high

number (96%) of respondents stating that organ donation

should be encouraged in SA [6]. It is therefore not surprising that

63% of participants had a positive attitude towards the

introduction of tan opt-out law on organ donation.

One factor that is likely to be discouraging the public from

opting in is the commonly held view that human body parts are

used as muti or sold on the black market for organ transplants

[7]. This was confirmed by the high number (81%) of

participants who believed that donated organs could be

misused.

The level of education of study participants was examined as

it has been showed in previous studies to have an influence on

the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards organ

donation. As expected, the level of education also had a

significant association with occupation, i.e. the majority of

occupied people had a higher level of education [8].

Results from this study are in agreement with the literature in

that it found both the participants level of education and

occupation to have a statistically significant association with

their attitude towards the introduction of the opt-out law.

A low number of participants (8.2%) did not think that the

opt-out law would encourage organ donation [9]. This suggests

that more efforts should be put into public education about

organ donation awareness and the proposed opt-out law.

Being married is a demographic factor that has been

associated with an increased likelihood to donate organs. There

was no significant association in this study between marriage

and having a positive attitude towards organ donation [10].

There was also no significant between age and having a positive

attitude towards the opt-out law.

The health care system in SA currently follows the opt-in

organ procurement method. The current legislation places no

urgency on both public members and the state to seek

information about organ donation, and the state to educate the

public on issues pertaining to organ donation so to encourage

informed decision making [11]. The legislation thus sets the

default position on organ as a ‘refusal to donate’ organs. It is for

these very reasons that the UK will be changing to the opt-out

system. It is similarly recommended that SA considers this

approach.

Conclusion

The majority of study participants who had heard about organ

donation before had good basic knowledge on organ donation

and had a positive attitude towards the donation of organs and

the introduction of an opt-out law. The significant association

between the level of education and the positive attitude

towards the introduction of an opt-out law is encouraging.

Better public education through mainstream school curricula,

traditional (TV drama series, radio, print) and social media

awareness campaigns can be used to disseminate information.

The SADoH already promotes the national organ donor

awareness month through its internet-based platforms,

however, public awareness is still lacking. It is therefore

necessary that the SADoH should be tasked with driving the

dissemination of information on the organ shortage crisis in SA

and the demystification of some commonly held false views,

especially because it has direct contact with communities

through its facilities, i.e. community health centers and

hospitals.

Celebrities have an influential role in SA and they usually

influence public opinion. They can be used to relate personal

stories to encourage the public to consider becoming donors.

Religious organisations should also become stakeholders

through being participants in this public awareness campaign.

When people are sufficiently educated, they become

empowered to make informed decisions and become less

susceptible to exploitation.

The ODF is not sufficiently visible in the public eye and a

public awareness drive should be undertaken. A larger study

with more participants in different areas should be conducted to

get a more accurate, holistic outlook.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

A much larger proportion (40.7%) of participants than

expected (i.e. 18%) had never heard about organ donation and a

limited number of respondents could therefore respond to the

main questionnaire. The study also had a small study sample

size (123 participants) and the generalizability of the results is

therefore questionable.

The assessment of participants Knowledge, Perceptions and

Attitudes (KPA) towards organ donation at this particular facility

which has a mix of different race groups, can however be used

to give insight into understanding of the rest of Gauteng

province’s urban resident’s KPA towards organ donation. The

study participants were only sourced from patients attending

ECHC oral health clinic who are in fairly good health, minimising

bias from participants. This precludes the extrapolation of

results to patients with serious health issues who may have very

different attitudes towards organ donation.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the research ethics

committee of the faculty of health sciences of the university of

Pretoria, as well as the Tshwane research committee affiliated to

the Gauteng department of health. All participants gave written

informed consent for the interviews. No personal information,

such as name and identity number, was collected and all

participants were assured of the anonymity of their data.

References

- Slabbert M, Mnyongani FD, Goolam N (2011) Law, religion and organ transplants. Koers 76:261-282

[Google Scholar]

- Cohen C (1992) The case for presumed consent. Transplant Proc 24: 2168-2172

- Rithalia A, McDaid C, Suekarran S, Norman G, Myers L, et al. (2009) Impact of presumed consent for organ donation on donation rates: A systematic review. BMJ 338: 3162

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda B, Vilardell J, Grinyo J (2003) Optimizing cadaveric organ procurement: The Catalan and Spanish experience. Am J Transplant 3:189-196

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Conco W (1972) The African bantu traditional practice of medicine: Some preliminary observations. Soc Sci Med 6:283-322

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McGlade D, Pierscionek B (2013) Can education alter attitudes, behavior and knowledge about organ donation? A pretest-post-test study. BMJ Open 3:003961

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Regalia K, Zheng P, Sillau S, Aggarwal A, Bellevue O, et al. (2014) Demographic factors affect willingness to register as an organ donor more than a personal relationship with a transplant candidate. Dig Dis Sci 59:1386-1391

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goodwin M. Black markets: The supply and demand of body parts. Cambridge University Press, New York. 2006

[Google Scholar]

- Cheadle MH, Davis DM, Haysom NR. South African constitutional law: The bill of rights. 2nd edition. LexisNexis Butterworths, Durban. 2005.

- Koffman G, Singh A, Bramhall S (2011) Presumed consent: The way forward for organ donation in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 93:268-272

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie IK. The pocket guide to critical appraisal. 2nd edition. John Wiley and Sons, UK. 2022.

Citation: Ndhlovu B ( 2023) Assessment of the Legal Framework and Participant Perceptions on Organ Donation in Tshwane, South Africa. Health Sys Policy Res Vol:10 No:4.