Abstract

Dependence on out-of-pocket payment (OPP) for healthcare may lead poor households to undertake catastrophic health expenditure; millions of people suffer and die because they do not have the money to pay for healthcare. Worldwide about 44 million households face financial problems due to healthcare expenditure; more than 40% of African nations’ health expenditure comes from out-of-pocket payments making a scarcity of funds for health, and lowincome groups make health payments by borrowing or selling property. Therefore, an agenda for developing a system of healthcare financing is common for all nations toward universal health coverage (UHC), using the emerging concept of community-based health insurance (CBHI) as a potential strategy to achieve universal health coverage in developing countries by discussing the problem of healthcare financing in low-income countries (LIC), helping to raise revenue, and narrowing the financial gaps of health sectors providing universal health coverage. Despite great efforts to improve accessibility to modern healthcare services in the past two decades, utilization of healthcare services in Ethiopia has remained very low. However, the functions of pooling funds and organizing them are critical for countries’ progress toward UHC.

Objective: This study aimed to assess willingness to pay, explore the mechanism of financial pooling for community-based health insurance, and identify factors associated with households in the Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia, in 2020.

Method: A community-based, quantitative and qualitative cross-sectional study was conducted from September to October 2020 in Tigray, Ethiopia. The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula. Multi-stage cluster sampling was used to select 845study participants and 10 KII and 4FGDs were selected using a purposive sampling technique. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire that was managed and analyzed using Epi-data Version 3.5.1 and SPSS Version 21.Theinterview guide used Atlas-ti software for qualitative data.

Results: Based on 845 households surveyed, more than half of respondents, 483 (57.2%), were female. The majority of the respondents, 743(87.9%), knew the current premium and registration fee of community-based health insurance (CBHI), with more than 90 percent, 790(93.5%), planning to renew/enroll their membership in CBHI, with the mean premium per household head they were willing to pay being 396 ETB (SD=±216) and 310 ETB (SD=±115) per household annually for urban and rural, respectively. In addition, six out of ten (62%) urban dwellers and five out of ten (52%) rural dwellers wanted to pay an additional amount of money to the current governmental premium threshold (which is 240 ETB for rural and 350 ETB for urban).

Conclusion: Community-based health insurance is an effective means of increasing the utilization of healthcare services and providing a scheme for member households with a pool mechanism situated at the district level, enabling districts to own the scheme, a decentralized health system, and decentralized decisions, ensuring equity. To alleviate deficits and make CBHI increases in the annual premium and enrollment of the community to CBHI sustainable, budget subsidization by the government to reverse the ruin, increased community awareness, and continuing the current pooling mechanism at the district level, but establishing or revising a department at the health office that controls the process of CBHI, are recommended.

Keywords

Community-based health insurance; Healthcare utilization; Healthcare financing

universal health coverage; Financial pooling

Abbreviations

ANC: Ante-Natal Care; CBHI: Community-Based Health Insurance;

ETB: Ethiopian Birr; EPSA: Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Supply

Agency; FGD: Focus Group Discussion; HEP: Health Extension

Programme; HEW: Health Extension Workers; KII: Key Informant

Interview; LIC: Low Income Country; MOU: Memorandum of

Understanding ; OOP: Out of Pocket; OPP: Out of Pocket Payment;

SD: Standard Deviation; UHC: Universal Health Coverage; USD:United States Dollar; WIP: Willingness to Pay

Background

Globally, approximately 44 million households (more than

150 million people) face financial problems due to healthcare

expenditure [1]. In the majority of African countries, more than

40% of the total health expenditure is by out-of-pocket payment

(OPP), which results in a scarcity of funds for health [2]. More

than 90% of healthcare financing problems have been reported

in sub-Saharan African countries, where resources are limited

[3,4].The economic burden of direct payments worsens among

people in lower income groups because healthcare demands outof-

pocket payments by borrowing or selling property [5,6]. As

a result, developing healthcare financing systems is a common

agenda and key area for health system actions toward universal

health coverage (UHC) [3] for all countries [3,4-7]. Community-

Based Health Insurance (CBHI) is an emerging concept for

providing financial protection to healthcare financing problems

in low-income countries that involves the mobilization of

resources for the health sector (revenue raising),accumulation

and management of prepaid financial resources(pooling), and

allocation of pooled funds (purchasing) [3,8]. Among others,

South Korea, Ghana, and Rwanda are the best examples of lessons

learned from developing countries, while South Korea is often

cited as a success story for its rapid achievement of universal

health coverage through community-based health insurance

[1,3]. However, in most African countries, healthcare financing

covers almost exclusively the formal sector and achieves no more

than 10 percent of population coverage [3,9].

Pooling arrangements and their potential to contribute to

progress toward UHC have received much less attention.

However, the function of pooling and the different ways in which

countries organize this is critical for their progress toward UHC

[10,11]. According to evidence from [13], fragmentation in pooling

is a particular challenge for UHC objectives. Pools are fragmented

when barriers exist in the redistribution of prepaid funds. This results

inefficiency in the healthcare system, as it typically implies duplication

(or multiplication) in the number of agencies required to manage

pools (and, usually, purchasing as well) [11,12]. Low adhesion rates,

limited resource mobilization, and poor sustainability have been the

challenges to in effective implementation of the CBHI scheme in

some sub-Saharan African countries [9].

The government of Ethiopia has introduced community-based

health insurance (CBHI) as a strategy for reducing catastrophic

financial shocks in our country, and it has been piloted in 13 selected

districts in Amhara, Oromia, Southern Nations, Nationalities,

and Peoples (SNNP), and Tigray [11,12]. Community-based

health insurance benefit packages are available for all services in

health centers and hospitals, excluding tooth implantation and

eyeglasses, with a provider payment mechanism making an effort

to remove financial risk through the expansion of CBHI [14-16].

According to the Health Sector Financing Reform (HSFR) project

report, the overall enrollment was 48% [12]. However, evidence

has shown that utilization of the scheme was affected by different

socio demographic, economic, and health-related factors,

including the study region in Tigray, northern Ethiopia [12,13].

Understanding the CBHI pooling setup and the community’s

willingness to pay (WTP), determining the amount of money, and

exploring facilitators and barriers while implementing the scheme

are necessary for policy makers to redesign and reform options,

and to expand the program regionally. Therefore, the objective

of this study was to assess the CBHI pooling setup, WTP for CBHI,

and associated factors among rural and urban households in the

Tigray region of Northern Ethiopia.

Methods

A community-based, quantitative and qualitative cross-sectional

study design was employed from September 1 to October 20,

2020 in an urban-rural community of selected districts in Tigray

Region, which is located in northern Ethiopia, hosting seven zones

(one special zone), 93 districts (71 rural and 22 urban) with 814

kebeles (the smallest administrative unit) and a total projected

population of 6,960,000 (CSA 2007 census projected for 2015),

with 90% overall health service coverage of the region [15,16].

All urban-rural households in the districts that had (not yet)

established the CBHI scheme were the source population,

whereas the study population comprised sampled households in

the selected districts. Household heads that had lived for more

than six months in the kebele and who were ≥18 years of age

were included in the study. Respondents who were working in

the formal sector or unable to participate in the interview due

to health conditions were excluded from the study. Respondents

working as focal persons of CBHI in regional health bureaus,

district health offices, and health insurance agencies, zonal

coordinators, district and kebele administrators, representatives

of the kebele’s cabinet, and health extension workers were

eligible for the qualitative study.

The sample size was calculated using a single-population

proportion formula with the assumption of proportion of

willingness to pay (WTP) for CBHI (p=80%) in Fogera District,

Ethiopia [17] using the95% confidence interval (Z=1.96) and a 4%

margin of error. After considering a design effect of 2 and adding 10% for a potential non-response rate, the final sample size was

845 households. For the qualitative part, 10 KI and 4 FGD were

interviewed with key actors of health insurance representatives

at each selected district and kebele.

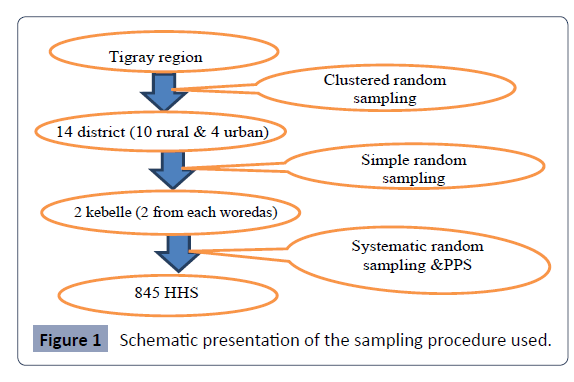

A multistage sampling technique was used to select the study

participants. To reach the final sample size, the first 14 districts

out of the seven zones were selected using cluster sampling and

then 2 kebeles from each district using simple random sampling,

and finally the households’ proportion to size was sampled using

systematic random sampling from each kebele. In the first stage

of sampling, 28 kebeles from 14 districts were randomly selected

from the region. In the second stage, households were selected

from these by systematic random sampling and probability

proportionate to size (PPS), for which a purposive sampling

technique was used.

The dependent variables are willingness to pay and the financial

pooling mechanism for CBHI. Willingness to pay means the

maximum (non-zero) amount that households are willing to

pay for the insurance scheme, elicited through a double-bound

contingent valuation method specifically by applying a bidding

game. Independent variables, such as socio demographic

characteristics (age, sex, marital status, educational status, family

size, religion, and ethnicity), economic factors (wealth index

and occupation), environmental factors (distance from health

institution in walking time), health and health-related factors

(health condition of illness, chronic illness and disability, medical

treatment for the recent episode, healthcare cost of the recent

treatment, perceived quality of the healthcare service in the

area), and knowledge-related factors(awareness of CBHI and

social trust) were independent variables in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure used.

The wealth index questionnaire was adapted from the Ethiopian

Health Insurance Agency for the number and types of consumer

goods owned, housing characteristics, and availability of basic

amenities for residents. From these, scores were derived using

principal component analysis and classified into five quintiles.

Quantitative data were collected from selected CBHI members

and non-member households using pre-tested intervieweradministered

structured questionnaires adopted from other

studies conducted in similar areas. The survey questionnaires were

developed to elucidate information on the basic demographic

and socioeconomic characteristics of the households, incidence of illness, and subsequent choice of health providers, and the

amounts and sources of money used to finance healthcare

services for illness for themselves and family members. The survey

questionnaire was administered in Tigrgna, the working language

of the state which most study area residents adequately listened

to and spoke. Fifteen trained data collection teams were used for

data collection, and each team comprised three data collectors

and one field supervisor. Supervisors spot-checked the quality of

data collection and ensured the questionnaires were completed

daily. The qualitative study respondents purposively selected

included board members and general congress, the Agency of

CBHI, the Zonal Administration, the Woreda Health Office, the

Woreda Administration, and the Regional Health Bureau. Ten key

informant interviews were conducted in each woreda with four

focus group discussions, one in each of the selected woredas,

with eight participants in each group.

An effort was made to include participants with a range of

characteristics in order to obtain a broad representation of

CBHI management and budget administration. Data were

gathered using a prepared FGD guide that was introduced to

the participants, describing the objective of the study, and was

followed by open questions cantering on the CBHI and the sum

of money made available for the purpose of the scheme. Trained

moderators facilitated all FGDs, with discussion notes taken and

audio recordings made.

Contingent valuation was used to elicit WTP for oneself, for other

members of the household, and also for altruism (for poor and

impoverished people in the community) using only the bidding

game technique (Dong et al. 2005). Three iterations were used

in the bidding game depending on the answer to the starting

bid. The final response was a continuous quantitative amount

that indicated respondents’ maximum WTP. A brief introductory

explanation and scenario regarding health insurance was provided

to the respondents before determining their WTP for the scheme.

The concept of CBHI and its attributes were explained before

starting the bidding game.

Quantitative data were analyzed using Epi-data Version 3.5.1,

and SPSS Version 21. Frequencies and proportions were used

to describe categorical variables using cross-tabulation. Factors

associated with the outcome variable with P<0.20 in the bivariate

analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression,

data from focus group discussions and KII were transcribed, and

responses were classified into general categories identified in the

discussion and interview guide using Atlas-ti software. A common

theme was identified, inferences were made from each theme,

and conclusions were drawn.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the IRB of the Tigray Health

Research Institute. Support letters were obtained from the

Tigray Regional Health Bureau, and Health Office permission was

obtained from the kebeles’ administration prior to conducting the

study. Written consent was obtained from the respondents prior

to the interview by explaining the purpose of the study as the IRB of

the THRI had already accepted and approved it. The confidentiality

of their information was assured using a coding system and by

removing any personal identifiers. Respondents’ right to refuse to

answer several or all of the questions was respected.

Results

Description of study participants

Of 845 sampled respondents, more than half, 483 (57.2%), were

female. A total of 810(95.9%) were Christian Orthodox, followed

by 35(4.1%) Muslim/Catholic; 840 (99.4%) were Tigrayan, the

majority of them, 607(72%), rural dwellers; and 267(31.6%) were

between the ages of 29 and 39 years. Among them, 581 (68.8%)

were married, followed by 116(13.7%) divorced/separated,

75(8.9%) single and 73(8.6%) widowed, respectively. More than

half of the respondents, 500(59.2%), had family size less than or

equal to five, whereas 345(40.8%) had family size greater than

five.

In total, 554 (65.6%) had two or more, 169 (20%) exactly one,

and 112 (14.4%) no family members of age 18 years or older

currently living with them. The majority of the respondents,

385 (45.6%), have no family members younger than 5 years

old, whereas 110 (13%) and 350 (41.4%) had two or more and

exactly one, respectively. Similarly, of the total respondents only

89 (10.5%) had one or more family member age 65 years and

older. Of the respondents, 440(52.1%) and 141(16.7%) were

farmers and daily laborers, respectively followed by merchants,

93 (11%), housewives, 89 (10.5%), and others, 82 (9.7%). Looking

at the educational background of respondents, 309 (36.6%), 135

(16%), 252 (29.8%), 139 (16.4%), and 10 (1.2%) were unable to

read and write, could read and write, had primary school, had

secondary school, and had college or above. In total, 329 (38.9%)

of the respondents’ wealth indices were below the median level

and are poor and poorest, whereas 342 (40.5%) were above the

median level and are rich and richest (Table 1).

| Characteristics |

Number |

Percentage |

| Sex of respondent |

|

|

| Male |

363 |

42.7 |

| Female |

482 |

57.3 |

| Age of respondents |

|

|

| <=29 years |

172 |

20.3 |

| 30-39 years |

267 |

31.6 |

| 40-49 years |

171 |

20.2 |

| 50-59 years |

112 |

13.3 |

| >=60 years |

123 |

14.6 |

| Religion |

|

|

| Orthodox |

810 |

95.9 |

| Muslim/Catholic |

35 |

4.1 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

| Tigrain |

840 |

99.4 |

| Amhara |

5 |

0.6 |

| Marital status of respondents |

|

|

| Single |

75 |

8.9 |

| Married |

581 |

68.8 |

| Widowed |

73 |

8.6 |

| Divorced/Separated |

116 |

13.7 |

| Residence of the respondent |

|

|

| Rural |

607 |

71.8 |

| Urban |

238 |

28.2 |

| Household/family size |

|

|

| Greater than 5 |

345 |

40.8 |

| Less than or equal to 5 |

500 |

59.2 |

| Household having member ≥18 years old |

|

|

| No having ≥18 years old |

122 |

14.4 |

| Having one |

169 |

20 |

| Having two or above |

554 |

65.6 |

| Household members younger than 5 years old |

|

|

| No child |

385 |

45.6 |

| Having one child |

350 |

41.4 |

| Two or above |

110 |

13 |

| Household members older than age 65 years |

|

|

| No older age |

756 |

89.5 |

| One or above |

89 |

10.5 |

| Occupation of the respondent |

|

|

| Farmer |

440 |

52.1 |

| Housewife |

89 |

10.5 |

| Merchant |

93 |

11 |

| Daily laborer |

141 |

16.7 |

| Others |

82 |

9.7 |

| Educational status of the respondent |

|

|

| Unable to read and write |

309 |

36.6 |

| Read and write |

135 |

16 |

| Primary school |

252 |

29.8 |

| Secondary school |

139 |

16.4 |

| College or above |

10 |

1.2 |

| Wealth Index |

|

|

| Poorest (1st quintile) |

164 |

19.4 |

| Poor (2nd quintile) |

165 |

19.5 |

| Medium (3rd quintile) |

174 |

20.6 |

| Rich (4th quintile) |

180 |

21.3 |

| Richest (5th quintile) |

162 |

19.2 |

Table 1. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the study participants in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia, 2020 (N = 845).

Health and health-related characteristics

Out of the total sample size, 84 (9.9%) respondents had a history

of chronic illness, and of the total respondents 250(29.5%) had at

least one episode of acute illness in the last six months and almost

all (92%) of them sought treatment for their recent episodes,

with 136(59.4%), 70(30.6%), and 23(10%) in public health

centers, hospitals, and private health facilities, respectively. Of

the total participants, 611(72.3%) lived close to health centers

and 234(27.7%) to hospitals (Table 2).

Characteristics |

Number |

Percentage |

| Have history of chronic illness |

|

|

| Yes |

84 |

9.9 |

| No |

761 |

90.1 |

| Encountered any illness during the last 6 months in the family |

|

|

| Yes |

250 |

29.6 |

| No |

595 |

70.4 |

| Have sought and received medical care (n=250) |

|

|

| Yes |

229 |

27.1 |

| No |

21 |

2.5 |

| Place where you receive treatment (n=250) |

|

|

| Public health center |

136 |

59.4 |

| Private health facility |

23 |

10 |

| Public hospital |

70 |

30.6 |

| Nearest health facility to your home |

|

|

| Hospital |

234 |

27.7 |

| Health center |

611 |

72.3 |

Table 2. Health and health-related situations of participants in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=845).

Awareness of head of household

The results revealed that the majority of respondents, 796

(94.2%), had heard about community-based health insurance

(CBHI). Nearly two-thirds of the respondents received CBHI

information from health extension workers and were aware

that CBHI is not like a saving scheme; that is, they will not earn

interest in their premium payment, nor will the premium be

returned even if they do not use health services, but rather that

the premium is a payment to finance future health costs. Besides,

more than 70% of the households had information that not only

the poor are members of the CBHI.

Practice of household heads toward CBHI

Of the total 845 household members covered in this survey,

433 (51.2%) were insured with the scheme through their own

contributions. More than half of the surveyed households had less than or equal to two years of enrolment. More than two-thirds of

the members paid a premium at the Kebele administration office.

Members were asked why they joined the CBHI scheme; around

one-quarter clarified that they did not know enough about the

CBHI scheme (Table 3).

Characteristics |

Number |

Percentage |

| Insurance status |

|

|

| Insured |

433 |

51.2 |

| Not insured |

399 |

47.2 |

| Insured but not renewed |

13 |

1.5 |

| Length of enrollment |

|

|

| Less than/equal to 2 years |

241 |

54 |

| Greater than 2 years |

205 |

46 |

| Time taken, after payment of registration fee and premium, to start utilizing health services(n=446) |

|

|

| Greater than 30 days |

286 |

64.1 |

| Less than 30 days |

160 |

35.9 |

| Where do you pay the premium |

|

|

| At the CBHI office |

76 |

17 |

| At kebele administration office |

309 |

69.3 |

| Official comes and collects |

61 |

13.7 |

| Why did you decide to enrolling CBHI (n=699) |

|

|

| Illness and/or injury occurs frequently in our household |

163 |

23.3 |

| To finance healthcare expenditure |

271 |

38.8 |

| Premium is low compared to the user fee price to obtain medical treatment |

224 |

32.04 |

| Pressure from other family members/community |

10 |

1.43 |

| Pressure from the CBHI office |

31 |

4.43 |

| Why did you decide not to enroll in CBHI (n=404) Number percentage |

|

|

| Illness and injury does not occur frequently in our household |

48 |

11.88 |

| The registration fee and premiums are not affordable |

77 |

19.06 |

| Want to wait in order to confirm the benefits of the scheme from others |

57 |

14.11 |

| We do not know enough about the CBHI scheme |

93 |

23.02 |

| There is limited availability of health services |

36 |

8.91 |

| The quality of healthcare services is low |

36 |

8.91 |

| The benefit package does not meet our needs |

31 |

7.67 |

| CBHI management staff are not trustworthy |

13 |

3.22 |

| Waiting time to access services is longer for CBHI members |

13 |

3.22 |

Table 3. Practice of household head toward CBHI in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=845).

Household head’s knowledge of CBHI benefit packages: The

majority of the households, 805(95.3%), thought regarding health

and health-related expenditure that CBHI is good way of helping

clients with health expenditures. In addition, approximately 80

percent, 672(79.5%), of household heads knew that CBHI covers

only care within the country. Similarly, 91.8% of respondents

knew that CBHI covers for both outpatient and inpatient

health expenditure. On the other hand, about 324(38.3%) and

235(27.8%) of household heads did not know that CBHI does not

cover medical care for cosmetic values and transportation fees,

respectively. Generally, in this study, the overall knowledge status

of respondents regarding what CBHI is, how it works, and its

concepts and purpose was 521(61.7%) respondents.

Willingness to pay: In this study, the majority of the respondents,

743(87.9%) know the current premium and registration fee

of community-based health insurance (CBHI) and 790(93.5%)

plan to renew/enrolled their membership of CBHI. However,

267(36.7%) respondents felt that the premium for CBHI per

household is inadequate. Hence, greater than 60%, 121(62.7%)

respondents were urban communities and about 279 (52%) from

rural communities suggested to increase the current premium

for CBHI. The mean annual amount of money (premium) per

household head they were willing to pay was 396 ETB (SD=±216)

for urban and310 ETB (SD=±115) for rural areas per household

annually. Similarly, the average amount of money they were

willing to pay for registration fees for CBHI was 18.9 (SD=±12.5)

(in Birr).

Benefit of CBHI among households: Of the total CBHI members,384(86.1%) respondents were assured that they benefitted

from the CBHI. Reduced costs of healthcare for 237(61.7%)

respondents were among the dominant benefits they received.

Of the respondents, 62(13.9%) believed that they did not benefit

from CBHI, and none of their HH members visited HFs for 41

(66.1%) respondents, paying additional costs for treatment for

17(27.4%) respondents, poor quality service for CBHI members

for 14(22.6%) respondents, and delay in issuing and distribution

of CBHI ID cards for 13(21%) respondents were some drawbacks

of CBHI.

Level of satisfaction of respondents toward the

quality of health services

Household satisfaction with the CBHI scheme was rated using

17 items, each having a 5-point scale from strongly disagree

to strongly agree. During the last six months, the number of

household heads visiting a health facility was 250(29.6%), of which

140(16.6%) visited health centers, 49(5.8%) both a hospital and

health center, and 61(7.2%) a hospital only, respectively. Those

who visited HFs more than once was 140 (56%) respondents,

while only once was 110 (44%) respondents.

Household heads dissatisfied with the quality of health services

showed an average 1.6 decrease compared to household heads

who were satisfied, which was 58.6;24(9.6%) household heads

responded they were strongly satisfied with cleanliness of

the health facility while25/111(22.5%)household heads were

dissatisfied with attentiveness and adequate follow up by nursing

staff. Household heads who was satisfied with quality of health

services was 58.6% greater as compared to household heads

who were dissatisfied. Household heads who were satisfied with

availability of drugs/medical supplies (56.8%) and diagnostic

facilities (60.4%) increased as compared dissatisfied household

heads. Household head satisfaction with confidentiality and

service provider attitudes toward explaining health problems was

68.8% and 64%, respectively. Household heads who were neutral

for satisfaction with waiting time and waiting time between

services had a 19.8% increase as compared to household heads

who were satisfied.

Household heads who were strongly dissatisfied with service

provider friendliness were 11.2%, while those strongly satisfied

with respect to the service provider were 8%. Similarly, 8.3%

of household heads were satisfied with the members’ card

collection process. The overall score for household satisfaction

with the CBHI scheme was 75.6 (Table 4).

| Characteristics |

Number |

Percentage |

| Have you visited a health facility during the last 6 months |

|

|

| Yes |

250 |

29.6 |

| No |

595 |

70.4 |

| Frequency of health facility visiting |

|

|

| Once |

110 |

44 |

| Greater than once |

140 |

56 |

| Health institution/facility visited |

|

|

| Only hospital |

61 |

7.2 |

| Both hospital and health center |

49 |

5.8 |

| Only health center |

140 |

16.6 |

| Satisfied with the service you received during your visit/stay |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

13 |

5.2 |

| Dissatisfied |

44 |

17.6 |

| Neutral |

31 |

12.4 |

| Satisfied |

147 |

58.9 |

| Very satisfied |

15 |

6 |

| Satisfied with overall quality of service |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

4 |

1.6 |

| Dissatisfied |

39 |

15.6 |

| Neutral |

58 |

23.2 |

| Satisfied |

142 |

56.8 |

| Very satisfied |

7 |

2.8 |

| Availability of drugs/medical supplies |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

9 |

3.6 |

| Dissatisfied |

57 |

22.8 |

| Neutral |

42 |

16.8 |

| Satisfied |

126 |

50.4 |

| Very satisfied |

16 |

6.4 |

| Availability of diagnostic facilities |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

6 |

2.4 |

| Dissatisfied |

35 |

14 |

| Neutral |

58 |

23.2 |

| Satisfied |

129 |

51.6 |

| Very satisfied |

22 |

8.8 |

| Cleanliness of the facility |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

5 |

2 |

| Dissatisfied |

26 |

10.4 |

| Neutral |

43 |

17.2 |

| Satisfied |

152 |

60.8 |

| Very satisfied |

24 |

9.6 |

| Waiting time (from time of arrival in the health facility to seeing a health professional) |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

6 |

2.4 |

| Dissatisfied |

48 |

19.2 |

| Neutral |

42 |

16.8 |

| Satisfied |

145 |

58 |

| Very satisfied |

9 |

3.6 |

| Waiting time between services (e.g. between consultation and diagnosis) |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

5 |

2 |

| Dissatisfied |

42 |

16.8 |

| Neutral |

57 |

22.8 |

| Satisfied |

120 |

48 |

| Very satisfied |

26 |

10.4 |

| Friendliness of staff |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

8 |

3.2 |

| Dissatisfied |

38 |

15.2 |

| Neutral |

48 |

19.2 |

| Satisfied |

128 |

51.2 |

| Very satisfied |

28 |

11.2 |

| Respect from healthcare providers |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

6 |

2.4 |

| Dissatisfied |

35 |

14 |

| Neutral |

51 |

20.4 |

| Satisfied |

138 |

55.2 |

| Very satisfied |

20 |

8 |

| Attentiveness and adequate follow up by the nursing staff (inpatient only in hospitals) |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

8 |

7.2 |

| Dissatisfied |

17 |

15.3 |

| Neutral |

19 |

17.1 |

| Satisfied |

60 |

54.1 |

| Very satisfied |

7 |

6.3 |

| Quality of food and other inpatient amenities (inpatient only in hospitals) |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

3 |

2.7 |

| Dissatisfied |

22 |

19.8 |

| Neutral |

25 |

22.5 |

| Satisfied |

59 |

53.2 |

| Very satisfied |

2 |

1.8 |

| Satisfied with confidentiality |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

9 |

3.6 |

| Dissatisfied |

30 |

12 |

| Neutral |

39 |

15.6 |

| Satisfied |

142 |

56.8 |

| Very satisfied |

30 |

12 |

| Satisfied with service providers’ attitude toward explaining health problems |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

14 |

5.6 |

| Dissatisfied |

34 |

13.6 |

| Neutral |

42 |

16.8 |

| Satisfied |

137 |

54.8 |

| Very satisfied |

23 |

9.2 |

| Satisfaction with members card collection on process (only CBHI members) |

|

|

| Very dissatisfied |

35 |

7.8 |

| Dissatisfied |

71 |

15.9 |

| Neutral |

58 |

13 |

| Satisfied |

245 |

54.9 |

| Very satisfied |

37 |

8.3 |

| Overall satisfaction |

|

|

| Satisfied |

189 |

75.6 |

| Neutral |

52 |

20.8 |

| Not satisfied |

9 |

3.6 |

Table 4. Level of satisfaction of household heads toward quality of health service in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=845).

Factors associated with willingness to pay

To identify the factors associated with willingness to pay, bivariate

linear regression was used with the following independent

variables: sex, age of household head, marital status, residence,

household family size, occupation of respondent, educational

status of respondent, wealth index, illness in the last six months,

place receiving treatment, nearest health facility, place where

you hear about CBHI, level of awareness, length of enrolment,

knowledge status, overall satisfaction of health services, and

cumulative perceived perception of CBHI. Variables that were

associated with WTP in the bi-variable analysis (at P-value < 0.25)

were included in the multivariable linear regression model. After

adjusting for all other variables, 11 variables (age of household

head, residence, family size, occupation of respondent,

educational status of respondent, wealth index, nearest health

facility, place where you hear about CBHI, level of awareness,

knowledge status, and overall satisfaction with health services)

were identified as factors associated with willingness to pay the

CBHI schemes.

For a one-unit increase in age, i.e., when age increased,

willingness to pay increased by 0.86 (95% CI: 0.13, 1.70, P=0.009).

Changing from urban to rural regions resulted in decreased

willingness to pay by 79.6% (95% CI: -118.26,-40.85, p=0.001). A one-unit increase in family size resulted in a 5.26 point increase in

willingness to pay (95% CI: 0.16, 14.71; p=0.03), merchants were

83.4 times more willing to pay than farmers (95% CI: 8.66, 175.5;

p=0.05) whereas daily laborers decreased willingness to pay

by 68% compared to farmers (95% CI: -119.74, 16.54; p=0.01),

and changing from secondary school and above education to

unable to read and write decreased by 66% the willingness to

pay (95% CI: -71.06, 2.81;p= 0.007). When the wealth index

increased, willingness to pay increased 2.6 times (95% CI: 0.13,

14.35; p=0.009) and 12 times (95% CI: 1.21, 20.11; p=0.001)

among the rich and richest, respectively. When hospitals were

the nearest health facility, willingness to pay increased 57 times

(95% CI: 20.82, 94.43; p=0.01). The source of information on CBHI

being through neighbours, mass media, and health professionals

decreased willingness to pay by 74%, 72%, and 71%, respectively,

when compared with health extension workers. Having awareness

of CBHI was 49.18 times more willing to pay when compared with

those not aware. Those who were knowledgeable were 2.5 times

willing to pay compared with those not knowledgeable (95% CI:

0.05,10.05; p=0.03),and when compared with those not satisfied

with the service given, those who were satisfied were 27 times

willing to pay (95% CI: 3.36, 59.45; p=0.04) (Table 5).

| Characteristics |

Bivariate Analysis |

|

|

|

|

Multivariate Analysis |

|

|

|

| |

B |

95%CI |

|

P-Value |

|

B adjusted |

95%CI |

|

P-Value |

| Sex of household head |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

17.01 |

(-4.84, 38.87) |

|

0.13 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Female |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age of household head |

0.64 |

(-0.12,1.40) |

|

0.09 |

|

0.86 |

(0.13,1.70) |

|

0.009 |

| Religion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Orthodox |

-28.13 |

(-88.32,26.85) |

|

0.32 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Muslim/Catholic |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Marital status of household head |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Married |

1.56 |

(-22.17,25.29) |

|

0.13 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Widowed |

2.64 |

(-37.99,43.28) |

|

0.89 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Divorced/separated |

-28.49 |

(-60.51,3.53) |

|

0.08 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Residence of household head |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rural |

-86.29 |

(-109.7,-62.85) |

|

0 |

|

-79.57 |

(-118.26,-40.85) |

|

0.001 |

| Urban |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Household/family size |

6.75 |

(0.68,12.81) |

|

0.03 |

|

5.26 |

(0.16,14.71) |

|

0.02 |

| Household members ≥18 years old |

-2.55 |

(-11.19,6.09) |

|

0.56 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Household members youngerthan 5 years old |

-7.54 |

(-22.66,7.57) |

|

0.33 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Household members older than age 65 years |

-1.48 |

(-28.32,25.35) |

|

0.91 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Occupation of respondents |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Farmer |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Housewife |

14.19 |

(-20.62,49.01) |

|

0.42 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Merchant |

50.29 |

(15.29,85.31) |

|

0.01 |

|

83.44 |

(8.66,175.52) |

|

0.05 |

| Daily laborer |

-37.5 |

(-66.64,-8.36) |

|

0.01 |

|

-68.14 |

(-119.74,16.54) |

|

0.01 |

| Others*(petty traders, unemployed students) |

35.66 |

(-1.48,72.81) |

|

0.6 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Educational status of respondent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Unable to read and write |

-15.51 |

(-38.07,7.04) |

|

0.18 |

|

-34.13 |

(-71.06,2.81) |

|

0.007 |

| Read and write |

10.39 |

(-18.95,39.73) |

|

0.49 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Primary school |

7.71 |

(-15.94,31.35) |

|

0.52 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Secondary school |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wealth Index |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Poorest (1st quintile) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Poor (2nd quintile) |

0.81 |

(-26.57,28.19) |

|

0.95 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Medium (3rd quintile) |

3.28 |

(-23.65,30.21) |

|

0.81 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| Rich (4th quintile) |

-38.51 |

(-64.50,-12.53) |

|

0 |

|

2.6 |

(0.13,14.35) |

|

0.009 |

| Richest (5th quintile) |

37.28 |

(9.81,64.74) |

|

0.01 |

|

12.01 |

(1.21,20.11) |

|

0.001 |

| Have history of chronic illness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

-17.35 |

(-54.56,19.85) |

|

0.36 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

| No |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Encountered any illness during the last 6 months in the family |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

14.43 |

(-9.38,38.23) |

0.23 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| No |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Have sought and received medical care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

-3.65 |

(-79.39,72.09) |

0.92 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| No |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Place where you receive treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Public health center |

-16.98 |

(-46.58,12.62) |

0.26 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| Private health facility |

123.44 |

(59.51,187.38) |

0.001 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| Public hospital |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nearest health facility to your home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hospital |

72.82 |

(49.09,96.55) |

0.001 |

|

|

57.62 |

(20.82,94.43) |

0.01 |

|

| Health center |

1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

| Place where you obtain information/hear about CBHI (N=796) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Neighbors/friends |

-42.22 |

(-75.00,-9.45) |

|

|

0.01 |

-74.84 |

(-129.15,-20.52) |

|

0.007 |

| CBHI officials in public meeting |

-10.86 |

(-32.92,-11.19) |

|

|

0.33 |

|

|

|

NS |

| House to house awareness creation campaign |

-27.21 |

(-6.72,-61.13) |

|

|

0.12 |

|

|

|

NS |

| Mass media: TV, radio |

-88.75 |

(-125.45,-52.04) |

|

|

0.001 |

-72.96 |

(-128.67,-17.24) |

|

0.01 |

| Professionals in health facilities |

-28.53 |

(-53.69,-3.36) |

|

|

0.03 |

-71.37 |

(-107.91,-34.83) |

|

0.001 |

| Health extension workers |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Level of awareness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aware |

38.15 |

(14.65, 61.65) |

|

|

0.001 |

49.18 |

(12.59,85.77) |

|

0.009 |

| Not aware |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Length of enrollment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Less than/equal to 2 years |

-23.51 |

(-56.83,9.81) |

0.17 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| Greater than 2 years |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Time taken, after payment of registration fee and premium, to start utilizing health services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Greater than 30 days |

0.72 |

(-34.03,35.47) |

0.98 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| Less than 30 days |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Knowledge status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Knowledgeable |

1.8 |

(0.24,20.64) |

0.06 |

|

|

2.5 |

(0.05,10.05) |

0.03 |

|

| Not knowledgeable |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Benefited from the CBHIscheme |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

-25.09 |

(-74.62,24.42) |

0.32 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| No |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Overall satisfaction of health service |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Satisfied |

24.64 |

(10.14,73.45) |

0.23 |

|

|

27.32 |

(3.36,59.45) |

0.04 |

|

| Not satisfied |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cumulative perceived perception of CBHI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| High |

-19.72 |

(-41.65,2.21) |

0.09 |

|

|

|

|

NS |

|

| Low |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5. Factors associated with willingness to pay of household heads toward CBHI in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=845)

Community awareness and perception

According to most key informants, community awareness and

perception of CBHI have increased over time, and enrollment in

the scheme has also increased. However, as the premium for the

scheme is small, this affects the perception of some community’s

on being a member as they consider that they could not receive

quality services by paying such premiums. An expert curative and

rehabilitative case-team coordinator said:

“As observations, there are wrong perceptions from some

members of the community who said that through this low

premium, CBHI could not be as much more benefited.”

Furthermore, poor interest in enrolling when they feel healthy

and want to be a member when they are sick indicates poor

awareness of the system; in line with this, if members of the

scheme were not sick in the fiscal year, they felt compunctions

for the premium they paid.

CBHI coverage and sustainability: All key informants agreed that

CBHI coverage in their respective districts increased from year

to year, ranging from 52% during Ramma to 92% during Mokoni.

In 2012, E.C. shows huge inter-district coverage differences

of CBHI and sustainability problems due to gaps in community

mobilization for enrollment. Campaign mobilization focuses on

coverage rather than convincing the community of the aim of the

scheme. In a pilot district, CBHI coverage was increased, providing

aid such as wheat for enrolment, which affected community

sustainability in the scheme of some key informants:

Due to that wrong way, some community members considered

enrolment to CBHI as a benefit of to the government not as a

benefit of themselves” (District CBHI coordinator).

Most key informants of the districts confirmed that they faced

budget discrepancies/deficits due to incomparable premium

payment amounts, and low coverage of the CBHI enrolment and continuous market inflation are among other reasons. In addition,

one participant explained that most members of the scheme

were households who repeatedly got sick, and those who had no

history of illness were not members: .

“Most member of CBHI scheme is those who usually get sick and

those who did not usually get sick are not” (district curative and

rehabilitative case team coordinator).

On the other hand, increased healthcare demand, even for

health check-ups, from the community increases the budget

deficit for CBHI. Poor preparedness of health facilities was also

mentioned as a reason for problems with CBHI. Furthermore,

most participants confirmed that less focus from different levels

of leaders affected the sustainability of the scheme:

“Even as a region, when should work more to make it more

sustainable, we are always good in starting programmers but we

are poor to make programme become sustainable”(cluster CBHI

head).

Health facilities’ preparedness and service quality: Most participants declared that health facilities tried their best to

avail drugs and supplies adequately to satisfy the community.

However, because of the absence of drugs and supplies in the

market and the Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Supply Agency (EPSA),

clients are referred to private health facilities and this creates

dissatisfaction, even if they withdraw from the scheme. On the

other hand, some clients want to be referred to private health

facilities as they thought better treatments can be find there,

which is costly ruin of CBHI is highly increased up to 100,000

birr for the reimbursement of individuals. Furthermore, due to

a lack of preparedness, CBHI is becoming a source for the lack of

good governance in some health facilities, increasing community

dissatisfaction:

“If we failed prepare the community will engulf us for our failure"

(district CBHI coordinator).

According to reflections from some participants, increasing health

service utilization following CBHI implementation is negatively

affected by the rude character of health service providers:

“When clients repeatedly visit health facilities, some health

professionals are not happy by the workload due to CBHI and

even showed a rude character for clients for their repeated visit”

(district curative and rehabilitative case team coordinator).

Some participants explained the contribution of CBHI to improving

service quality through proper referral linkage because due to

CBHI the health facilities utilize the health tier system properly.

Thus, self-referral to higher levels of health facilities decreased

as clients did not want to cover half the payment for the service

they obtained, preventing unnecessary workload in higher health

facilities and underutilizing lower-level health facilities.

Some participants mentioned a public-private partnership

as a mechanism to prevent ruins in the CBHI. Furthermore,

informants noted that regulation of exaggerated drug and supply

costs in private health facilities should be practiced, and that such

measures are the responsibility of the functional state:

“We are regulating private health facilities for their quality

service provision, having expired drugs, and practicing other

unpermitted procedures, why do not we regulate them on the

cost of the services they asked? Nothing! We can regulate them”

(cluster CBHI coordinator).

Challenges: Participants indicated resource-related challenges

in the implementation of CBHI. Most participants underlined

the structural challenges of CBHI. Even if the implementation

among districts is not standardized, some districts have a CBHI

coordinator, while others do not, and responsibility is given to

curative and rehabilitative case team coordinators.

Most informants explained that the scheme had adequate

human power and budget limitations. Furthermore, negligence

in allocating an administrative budget to the scheme was

mentioned. Some participants reflected their grievances about

the poor ownership of CBHI by different bodies at each level of

management. Thus, for most informants, especially those directly

involved in the scheme, these challenges were described as the

cause of their dissatisfaction with the scheme:

“Though CBHI is a basic scheme to help the community, giving a

due focus as of its importance has remained low” (Cluster CBHI

coordinator).

“The focus given for CBHI by mangers in each level is not

satisfactory, and I feel sorry and even I think I will leave my job

if I get another better opportunity” (district CBHI coordinator).

Due to inadequate human power, premium collection and

utilization are negatively affected. Furthermore, this also affects

health extension workers performing other routine activities

because of their engagement in collecting revenues. Additionally,

according to the informants, revenue extravagancy is also in place

because of the absence of responsible bodies in each kebele:

Theoretically, in kebele during the collection of revenue, above

2000 birr should not be wait in the hands of the collectors; it

should be deposited to the nearby bank account, but in practice,

it is common to get, up to 80,000 birr in the hands of the revenue

collectors. Therefore, our revenue collection is not immune

from extravagancy, (district curative and rehabilitative case team

coordinator).

Another challenge faced by the informants was the restructuring

of districts. As districts are separated into different administrative

units, this delays the start of the scheme among newly emerging

districts and is challenging for the continuity of the scheme.

Recommendations/the way forward

For better CBHI implementation, a robust and effective pooling

system is critically important. One of the specific objectives of

this study was to identify where the pooling system for CBHI

should be situated, as a number of newly emerged districts have

been created for administrative purposes in the current Tigray. As

a result, 86% (n=24) of the key informants recommended that the

pool for CBHI should be situated at the district level. Participants

described their arguments regarding this issue: situating the

pool at the district level enables districts to own the scheme,

decentralizes the health system and decisions, and ensures

equity.

However, among the participants, three preferred the pool to

be situated at a regional level. Their argument was based on

the importance of focusing on the scheme at the regional level

and sharing responsibilities. Additionally, they also need to lead

the program through experience sharing to achieve a balanced

performance among districts, which they considered would

be better if handled by the region. However, one participant

preferred it to be situated in both districts and regions. His

argument was that this would solve the problems of delay during

signing the MOU among district health offices and hospitals.

Accordingly, he noted that districts should make agreements

with health centers and hospitals within the region. Thus, partial

pooling in both districts and regions is an option.

Furthermore, almost all participants recommended revising the

structure of CBHI and that adequate human power should be

employed. Adequate budget allocation for the scheme was also

recommended by most informants. In line with this, more than 80%

(n=23) of the participants recommended raising premiums due to

the existence of market inflation in the cost of drugs and supplies.

On the other hand, three participants agreed on increasing the

premium but they had concern with the community’s ability

to pay, even though they reflected that members of the CBHI

scheme could fail to renew their membership. Furthermore, one

participant indicated his preference for the total involvement of

the community, even with the current premium, before rushing

to increase it. However, media coverage was also recommended

to improve community awareness. The participants also

recommended budget subsidization from the government to

reverse the ruins. However, from the reflection of the participants,

other methods of resource mobilization are poor on the ground.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess WTP for CBHI, pooling mechanisms,

and associated factors among households in Tigray Region,

Northeast Ethiopia. This study revealed that six out of ten (62%)

urban dwellers and five out of ten (52%) rural dwellers wanted to

pay an additional amount to the current governmental premium

threshold (which is 240 ETB for rural and 350 ETB for urban). As

an average amount of premiums, households were willing to pay

per annum per household 396 ETB (10.7 USD) and 310 ETB (8.4

USD) (October 2020 exchange rate) for urban and rural dwellers,

respectively. This current finding is higher than the study findings

in Fogera district (187.4 ETB) [18] and Adama district (211 ETB)

[19], but lower than the studies in Ecuador[20] and other parts

of Ethiopia [21,22] which showed WTP an average of US$30,

US$16, and US$11.12 per year, respectively. This could be due

to differences in the elicitation methods of the initial bids and

changes in the value of money over time, area, design, and

participants. Nevertheless, it is far from the 34 USD (30 USD-

40 USD) recommended by the WHO in 2001 to deliver essential

healthcare in low-income countries like Ethiopia. Based on the

2014 report, the mean medical expenditure was 28.65 USD per

capita in Ethiopia. A study conducted in Gondar indicated that

the median total cost incurred by patients was more than 22.25

USD per visit.

The results of this study revealed that age of the household head

is significantly associated with willingness to pay for CBHI, and

a similar finding in Namibia and Tanzania showed that the age

of respondents affects their interest in and WTP for the scheme.

This might be because as the age of individuals increases their

income status also increases, or because as the age of individuals

increases their health status will be decreased. This result is

consistent with a study conducted in Nigeria which indicated

that rural residents were less likely to have WTP. This implies that

raising awareness is needed, especially in rural areas, and care

must be taken to fix the premium paid by different population

groups, which suggests that premiums should be adjusted for

income and that there should be exemptions and subsidies for

the poor to increase their willingness. Study participants who had

few family members were less likely to pay for the scheme than

their counterparts. This result is supported by studies conducted

in other parts of Ethiopia Nigeria, China and India which might

be because households with lower family sizes may consider

covering the cost of medical care for their families by OOP. Again,

this study’s results show that merchants were more likely to

be willing to pay than farmers, which is consistent with studies

conducted in other parts of Ethiopia. This might be a result of

their level of earnings and ability to afford high medical expenses,

given that families who are farmers (who are most often exposed

to poverty) are less willing to pay than merchants in the private

sector; policymakers must be aware that the poorest can be

excluded from such a scheme and either subsidize or lower

their premiums. The educational level of the respondents was

found to be another factor that increased the premium they

were willing to pay for the CBHI scheme, which is consistent

with studies conducted in Nigeria, Cameron and Burkina Faso

Educated household heads have better knowledge about the

advantage of making regular insurance payments to avoid the

risk of catastrophic medical expenditures at the time of illness,

and might also have better income, access to media, and easily

understand the benefits of participating in the health insurance

scheme.

The wealth status of families was positively and significantly

associated with WTP, which is similar to other studies conducted

in other parts of Ethiopia Fogera district Nigeria China and India

A possible explanation might be that wealthier people have

more WTP than the poor, which might be due to fear of high

asset losses if unexpected events could occur, implying that the

government should implement a co-payment system to enable

poor households to meet their requirements. Households that

are closer to hospitals are more willing to pay than those near

health centers; this is an issue of quality health services, so the

government should work more to equip health centers with

medical equipment and drugs. A study conducted in Conakry and

Guinea showed that poor quality of care in healthcare services is

one of the main causes of low and even declining enrolment in

CBHI.

HEW are more successful in disseminating information to

the community regarding CBHI than other methods such as

mass media and friends, which may be because a number

of identified successes were achieved by the HEP (family

planning, immunization, ANC, malaria, TB, HIV, and community

satisfaction) in the first five years of implementation. Service

utilization, improved knowledge and care seeking, increased

latrine construction and utilization, enhanced reporting of

disease outbreaks, a high level of community satisfaction and

HEWs as the primary source of information have increased

Respondents’ awareness of the CBHI scheme has a positive and

significant association with their WTP for CBHI. This finding is

consistent with those of studies conducted in Nigeria Cameron

and Myanmar This may be due to the catastrophic effects of

health problems and the benefits of joining insurance schemes

earlier. This implies that intensive awareness creation and trustbuilding

programs are required in the community, particularly for

those who do not have formal education and those who have not

been insured before. One qualitative participant indicated that:

“The community awareness and perception on CBHI has been

increased from time to time. Thus, the interest of enrolling to the

scheme is increased. However, there are some perceptions which

hinder the enrollment of the community like they considered the

scheme as the issue of the poor and they don’t consider getting

quality service through the seated premium [21,22].

The study indicates that the knowledge of respondents regarding

CBHI is significantly associated with willingness to pay, which

shows that each level of government sectors, in collaboration with

CBHI programmers, is more aware of the community about CBHI

benefit packages and their premiums. The level of satisfaction

with health service delivery affects willingness to pay for CBHI. In

2005, the World Health Assembly called on all countries to move

toward universal health coverage, especially developing countries

with huge inequalities in health service delivery Therefore, CBHI

enhances universal health coverage (UHC) if client satisfaction is

met.

Limitations

Some district CBHI focal persons were not available during

the data collection period, and data were collected from their

representatives, which may have its own drawbacks for decisions

which could, in turn, affect the pooling mechanism of CBHI.

Conclusion

The average amount of money households were willing to pay

per annum per household for CBHI of urban dwellers was 396

ETB (10.7 USD at October 2020 exchange rate) and of rural

dwellers was 310 ETB (8.4 USD at October 2020 exchange rate.

Age of the household head, residence, family size, occupation of

the respondent, educational status, wealth index, nearest health

facility, place where they obtained information about CBHI, level

of awareness, knowledge status, and overall satisfaction with

health services were identified as independent factors associated

with willingness to pay for the CBHI schemes. Regarding the

pooling mechanism, this should be located at district level.

Participants described their arguments regarding this issue:

situating the pool at the district level enables districts to own the

scheme, decentralizes the health system, makes decentralizes

decisions, and ensures equity. To alleviate deficits or to make

CBHI sustainable, factors include increasing the annual premium

and enrollment of the community to CBHI, budget subsidization

from the government to reverse the ruin, increase communitybased

awareness creation activities, and continue with the

current pooling mechanism at the district level, but establish or

revise a department at the health office that controls the process

of CBHI. Newly emerged districts should create their own pool in

their respective district.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no any conflicts of interest.

Authors Contributions

All authors conceived the study, performed the analysis,

and participated in designing the data collection tools, data

management, and writing of the manuscript. The authors agree to

be accountable for all aspects of the work related to its integrity.

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Tigray Health Research Institute,

Tigray Regional Health Bureau, health facilities, and study

participants for their cooperation during the study.