Key words

Craniotomy, awake, local anaesthesia.

Introduction

Awake craniotomy was first introduced in the 19th century for the removal of epileptic foci under local anaesthesia [1]. In the following years, the indications for awake craniotomy have extended to involve resection of brain tumours involving eloquent areas and finally, in more recent years, for removal of supratentorial tumours, regardless of the area involved of the cortex [2]. Due to financial constrains, the electro-cortical mapping tools used to permit for the detection and sparing of eloquent brain regions are not feasible to all centres, especially those in the developing countries. In this situation, the benefit of aggressive resection of space occupying lesion, which is made possible by allowing the patient to remain awake during the procedure, should outweigh the anticipated postoperative neurologic dysfunction.

To provide maximum resection with minimal postoperative neurological deficit, an adequate sedation and analgesia are mandatory to have an awake, cooperative patient for neurological assessment yet maintaining a patent airway, adequate respiratory function and haemodynamic stability. Airway control during sedation for awake craniotomy is a crucial part of the anaesthetic technique, but it remains the subject of debate. Different techniques have been tried for awake craniotomy, but no one has proved to be superior [2,3,4,5,6,7].

All indications for awake craniotomy, as we can see, have only focused on the tumour location without considering the degree of systemic impairment which, for most patients included in this study, represents a potential risk to life if tumour resection is performed under general anaesthesia.

In this study, we present twenty patients in whom craniotomy for brain tumour resection was performed while patients were awake. Craniotomy in our study was facilitated using scalp block and sedation with unsupported airway.

The main indication for the awake craniotomy was the patient’s clinical condition which is considered as an unusual indication. In our view, tumour resection under awake craniotomy for such indication will enables patients previously deemed inoperable to benefit from surgery.

Methods

In this prospective descriptive study, 20 consecutive patients in whom awake craniotomy was indicated, as a result of the patients’ clinical conditions being unfavorable for craniotomy to be done under general anaesthesia, were reviewed for safety and effectiveness of craniotomy under local anaesthesia and monitored conscious sedation.

All patients were operated awake for such specific unusual indication at the national center of neurological science at Shaab teaching hospital (Khartoum-Sudan) in the period from 2008 to 2012. An approval was granted from the ethical committee and an informed consent was obtained from the patients or their relatives.

A decision was made by both the anaesthetist and surgeon, to carry out surgery while the patient is awake following a thorough pre-operative clinical assessment and risk evaluation of surgical intervention under general anaesthesia. The details of the surgery and theatre environment (e.g. instruments and staff sounds) were explained to the patients.

On arrival to the operating theatre two wide pore intravenous canulae were inserted for fluid and medications and standard monitoring was applied.

Sedation was started upon skin incision and bone flap cutting, using 100-200μg of fentany with 20 to 50 mg propofol as an IV bolus followed by propofol infusion at a rate of 1.5 to 3 mg/kg/hour, targeting a Ramasy sedation score of 2 to 3, respiratory rate >8/min and haemoglobin saturation ≥95%. Oxygen was supplemented through a nasal cannula and a urinary catheter was inserted.

Patients were then placed supine with the head on a ‘head ring’ in neutral position or turned to one side with sand bag under the shoulder. The patient was supported with soft pillows to provide maximal intra-operative comfort. Draping was done in such a way that eye contact could be maintained with the patient for assessment and for the airway if emergency airway management was needed. A set of laryngeal mask airway was prepared to be used if airway obstruction develops intra-operatively.

Skin and bone flap were made following scalp block (Nerves targeted were supraorbital, supratrochlear, auriculotemporal, zygomaticotemporal, posterior auricular branches of greater auricular nerve, greater, lesser and third occipital nerves).

Bupivacaine without adrenaline was selected as most of the selected candidates were elderly and with cardiovascular diseases.

Following elevation of bone flap, the dura was installed with 5ml of 2% Lignocaine before incision and the intravenous sedation was then tailored down to facilitate functional assessment. Sedation was restarted upon closure of dura and was terminated at the end of skin closure.

Verbal communication was continuously maintained with the patient to assess the speech while hand and foot movements were also monitored.

During the procedure the following measurements were taken: sedation score (Ramasy scale, 1 to 6), pain score (0 no pain, 10worst imaginable pain), mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation and respiratory rate. These were documented at arrival to the operating room, at skin incision, every 30 min during tumor resection, at closure of the skin and in ICU for 30 minutes (every 5 minutes).

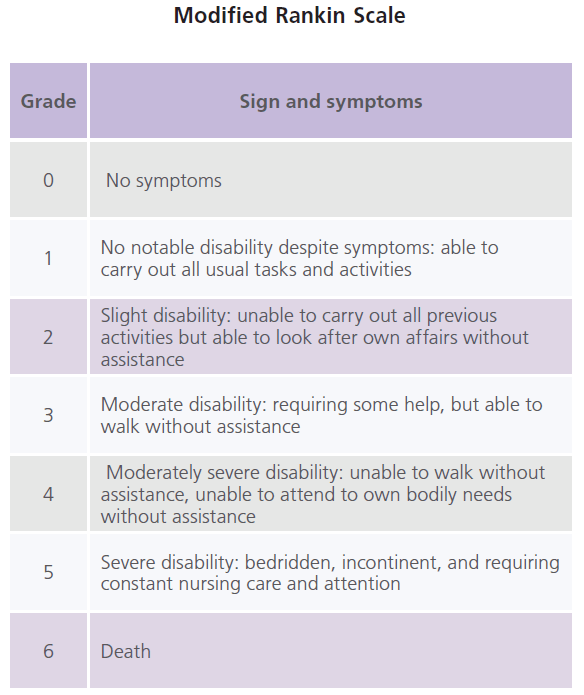

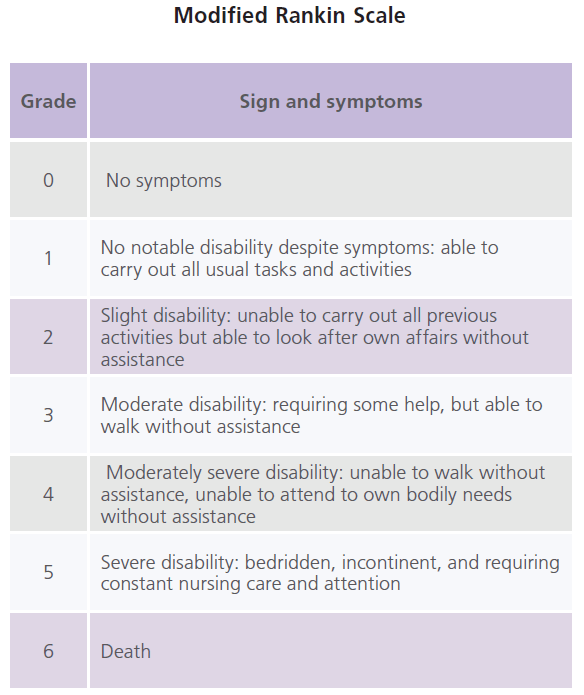

The incidence of anaesthetic (inadequate or excessive sedation, pain, nausea or vomiting), respiratory (oxygen saturation <90%, airway obstruction, or hypoventilation defined as<8 breath per minute) and haemodynamic (mean arterial blood pressure <50 or >150 mmHg and heart rate <50 or >100 beats per minutes) complications were assessed. The post-operative neurological status, using Modified Rankin Scale, was also assessed on discharge from hospital.

Obtained data were analyzed using SPSS and were presented in tables and figures. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were done for categorical variables and hypothesis was tested using chi-square for general trends, with reference p-value of 0.05 as the level of significance.

Table: Modified Rankin Scale

Results

In this study, twenty consecutive patients with space occupying lesions who were operated awake, in the period from 2008 to 2012, were studied.

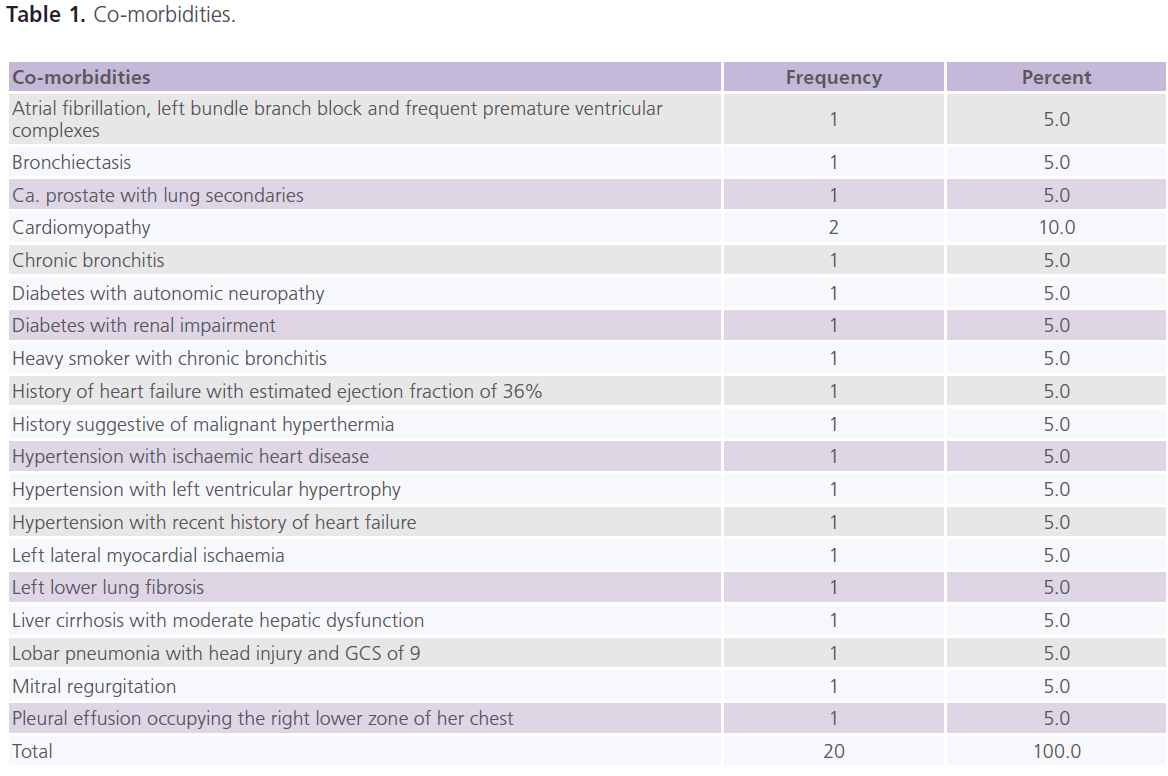

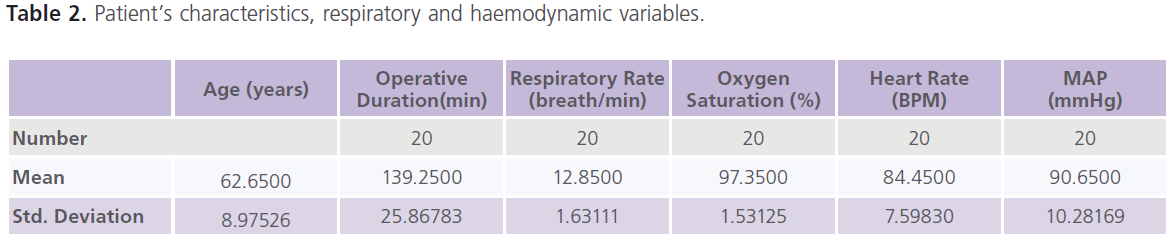

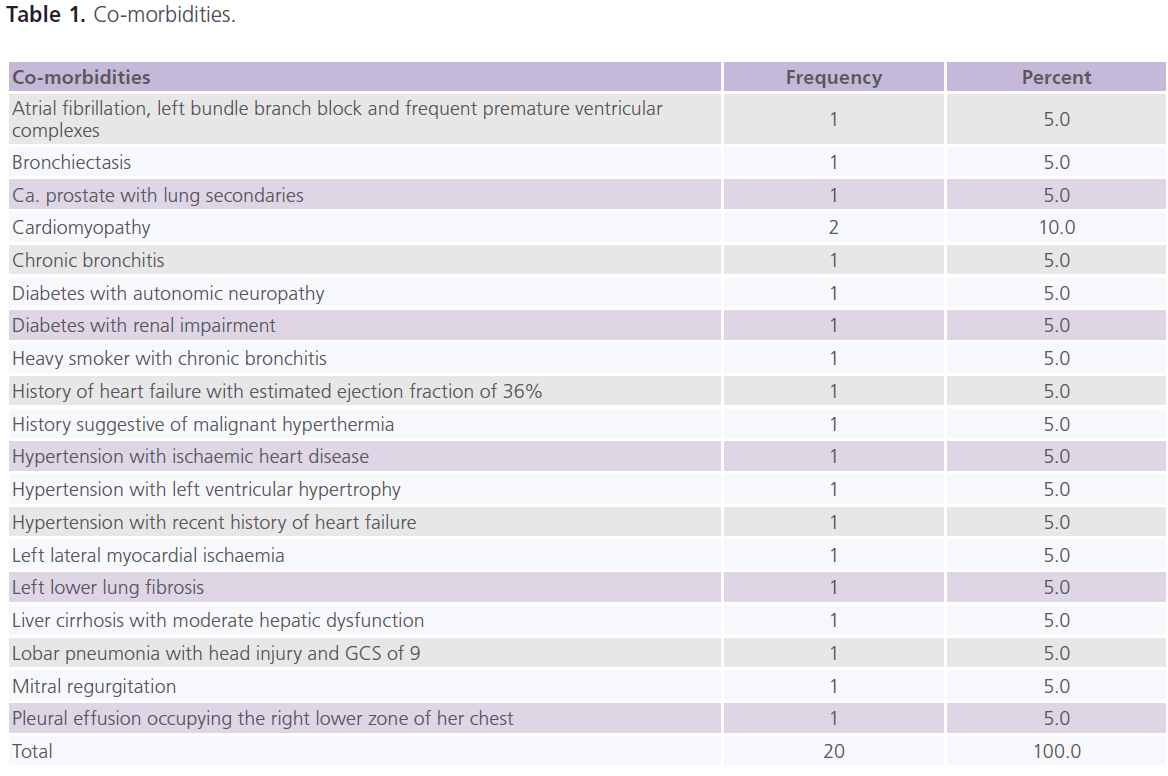

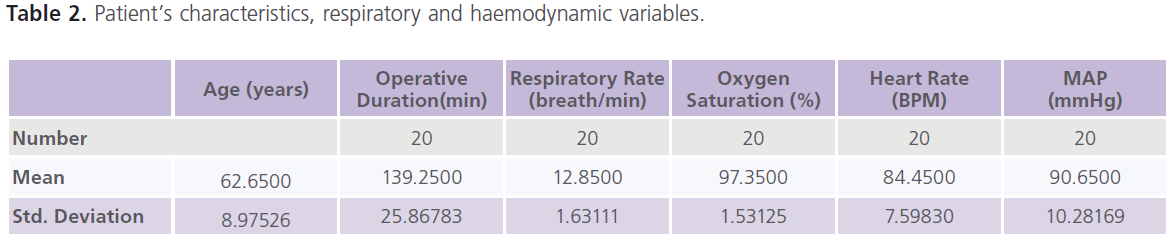

Most of the selected patients were elderly, with a mean age of 62.65 (STD±8.97) years (Table 2); and all of them were suffering from significant life threatening (mainly cardio-respiratory) co-morbid conditions (Table 1).

Table 1: Co-morbidities.

Table 2: Patient’s characteristics, respiratory and haemodynamic variables.

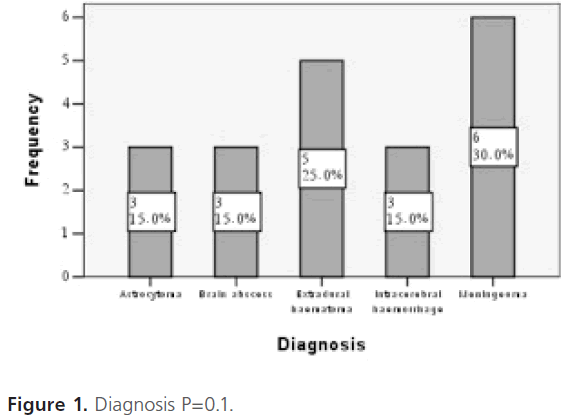

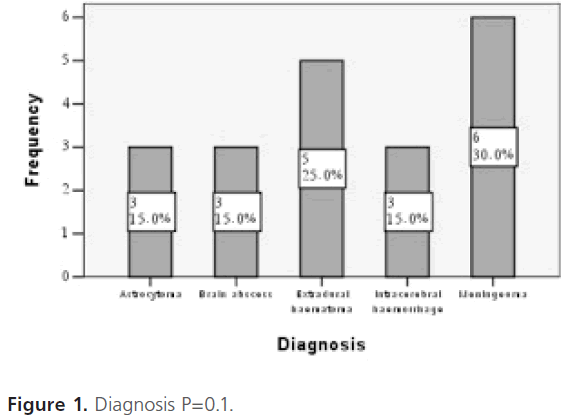

The MRI diagnoses of the space occupying lesions were as follows: 3 astrocytomas, 3 brain abscesses, 5 extradural haematomas, 3 intracerebral haematomas and 6 meningiomas (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Diagnosis P=0.1.

The mean operating time was 139.25 (STD±25.86) minutes. The intra-operative and early, the first 30 minutes, postoperative periods were characterized by stable respiratory functions (mean respiratory rate was 12.8 ± 1.63 breaths per minute and mean oxygen saturation was 97.35 ± 1.5%), haemodynamic stability (mean heart rate was 84.45 ± 7.5 beats per minutes and the mean of mean arterial pressure was 90.6 ± 10.2 mmHg) with no evidence of airway obstruction (Table 2).

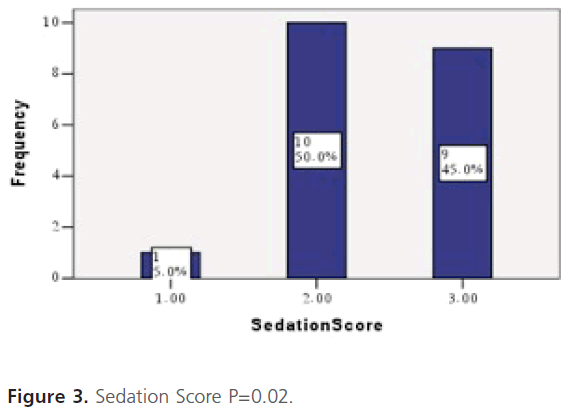

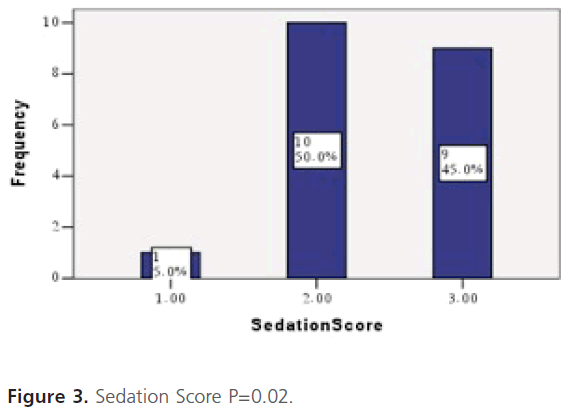

Intra-operatively, half of the patients had a sedation score of 2,9 patients (45%) had a score of 3 and only one patient (5%) had a score of 1. Sedation was increased to its maximum range for those patients whose score was 3 (Figure 3).The range of sedative dose used, significantly achieved the desired sedation score (p=0.02)

Figure 3: Sedation Score P=0.02.

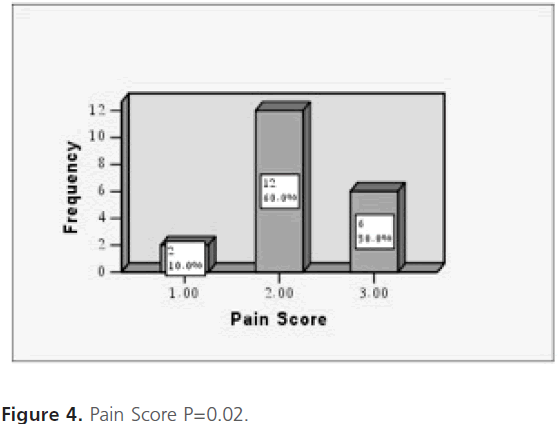

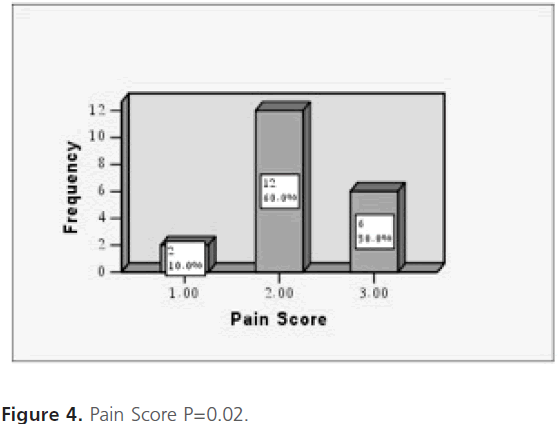

On assessing tolerance to craniotomy under local anaesthesia, most of the candidates well tolerated the procedure and the VAS ranged between 1 and 3 (2 patients (10%) had VAS of 1, 12 patients (60%) had a VAS of 2 and the remaining 6 patients (30%) had aVAS of 3) as shown in figure 4. The analgesic technique used significantly achieved the desired VAS for the procedure (p=0.02). No nausea and vomiting were reported.

Figure 4: Pain Score P=0.02.

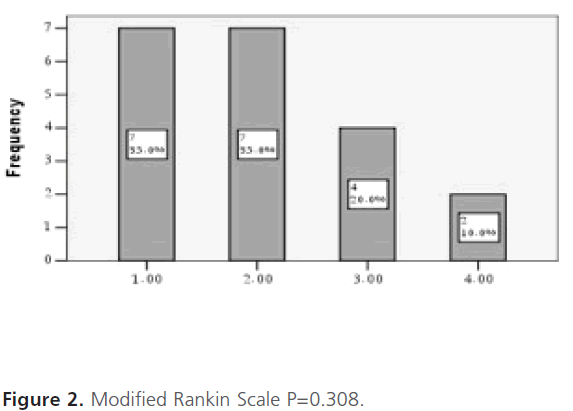

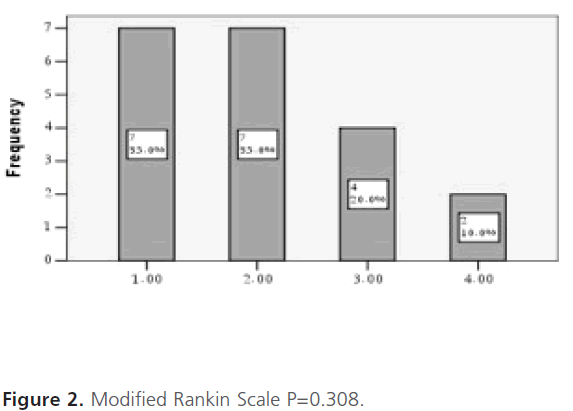

Postoperative neurological deficits were seen in two patients (Modified Rankin Scale of 4) who developed transient hemiparesis, and who were unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance (Figure 2). This was an insignificant incidence (p=0.308).

Figure 2: Modified Rankin Scale P=0.308.

Discussion

Awake craniotomy requires an adequate level of sedation during the opening and closure of bone flap without producing respiratory depression, full consciousness during brain stimulation and maximum comfort of patient throughout the procedure.

There is no consensus regarding the ideal anaesthetic techniques for awake craniotomy, but the common target for all techniques is to facilitate maximum possible tumour resection while sparing normal brain functions. Specific data analysis of patients with lesions in eloquent areas revealed a significantly better neurological outcome and quality of resection in the awake craniotomy group than the group of general anaesthesia patients with lesions in eloquent areas. Surgery was uneventful in awake craniotomy patients and they were discharged home sooner [8].

In this study, the mean duration of surgery was 139.25 (STD±25.86) minutes.

Craniotomy and resection of space occupying lesion usually takes more than 2 hours. Such lengthy operation time mandates a degree of sedation that should be titrated in such a way that the patient remains comfortable, motionless, conscious, alert and cooperative during resection of space occupying lesion and neurological assessment.

Patients may refuse to cooperate for different reasons including bad pre-operative preparation, under or over sedation, poor intra-operative analgesia, uncomfortable position and prolonged duration of surgery. Such events should be prevented rather than treated. Although the operation time in this study was not in favor of an awake patient to stay motionless and comfortable throughout the procedure, adherence to details of the ideal awake craniotomy technique helped to prevent these events.

Skin incision and craniotomy are the most painful phases of this operation. A rapid control and modulation of sedation and analgesia is absolutely mandatory to manage painful surgical stimuli.

The success of surgery greatly depends on adequate scalp block; otherwise patients may become restless and uncooperative, requiring higher doses of analgesics or sedatives which can interfere with functional assessment and airway patency. Bupivacaine 0.5% combined with adrenaline 1:200,000 may be used to carry out the block.

In this study analgesia was based on intravenous fentanyl and bupivacaine 5% without adrenaline for scalp block. Bupivacaine 5% without adrenaline was used in this study as most of our patients were elderly and most of them had some element of reduced cardiac reserve. The pain score ranged from 1 to 3 for all patients enrolled in the study, which is considered as acceptable, putting in mind inter individual variations in perception and interpretation of pain.

In the USA, the majority of these procedures are performed under local anaesthesia with sedation, and it has been suggested that this should be a standard approach to certain supratentorial tumours [9]. A shorter hospital stay and shorter use of high dependency facilities result in considerable cost reductions and some centres are even advocating day-case procedures [10].

Underestimating the benefits of tumour resection in an awake patient had led to reluctance of some surgeons, in our centre, to perform craniotomies under local anaesthesia as a routine technique, guided by the false impression that the depth of sedation required may be associated with an increased incidence of complications. This may be true if the sedation level is not controlled or vigilantly assessed. Oversedation results not only in an uncooperative patient, but may also lead to respiratory depression.

An adequate level of sedation was achieved in this study by using a target infusion of propofol. The advantages of using propofol for sedation include short duration of action, amnesia, antiemetic action, reduced incidence of seizures and minimal effects on ventilation in low doses.

Airway obstruction should not be allowed, as it can lead to hypoxia, hypercapnia and increased brain tension. All airway management techniques used for awake craniotomy has their advantages and disadvantages and no technique has proved to be ideal. The most appropriate techniques should be chosen according to each patient’s requirements and the available facilities.

Huncke and colleagues [4] kept the trachea intubated during opening and closure of the skull and extubated during cortical mapping. They reportedly managed tracheal intubation, extubation, and reintubation with the patient’s head firmly positioned in a three-pin headholder. Lignocaine was continuously delivered to the upper airway via a catheter with multiple holes spiraled around the tracheal tube to avoid coughing and gagging at extubation and re-intubation. Although this will provide adequate ventilation, the process of extubation at light planes of sedation is still stimulating and re-intubation is difficult with fixed head position. Continuous topical anaesthesia to the upper airway might result in loss of airway reflexes, leading to aspiration postoperatively. Tongier and colleagues [5] used a laryngeal mask airway, which is easier to insert and less stressful to patients than tracheal intubation. However, the technique has got similar disadvantages compared to endotracheal intubation. Alternatively awake craniotomy has been conducted without airway support and with oxygen supplementation through a nasal cannula [2,3,6,7-11]. This technique, although comfortable, carries the risk of depression of ventilatory drive [2,3,6,7-9], transient desaturation and hypercapnia [6,7-9].

Weiss [12] placed a nasopharyngeal airway, which was then connected to a breathing circuit via a tracheal tube connector, thus enabling patent airway and assisted ventilation.

In this study, the main indication for awake craniotomy was influenced by the patient’s critical condition, which seems to be an unusual indication. However, the technique used adequately met the requirement for a craniotomy to be done in an awake patient, with no incidence of intra or postoperative complications. The procedures were done in well sedated patients, but still arousable with good tolerance and with satisfactory surgical conditions. Among all the candidates of the study, no patient was converted to general anaesthesia.

Having a patent airway is a crucial part of the surgical procedure. In all patients, we conducted the awake craniotomy without airway support, while being prepared for airway obstruction with a set of laryngeal mask airway.

We believe that the process of extubation and re-intubation during surgery, with the patient’s head in a fixed position and with limited area for movement of the anaesthetic staff, seems to be difficult and equally stimulating to the patient and inconvenient to the surgeon.

Although an unsupported airway technique was used, with nasal oxygen supplementation, saturation (97.3500% ±1.53125)and airway patency were well maintained, and the patient remained haemodynamically stable (heart rate 84.4500±7.59830and MAP90.6500 ±10.28169) throughout the procedure. Minor degrees of airway obstruction were encountered in two patients on deepening sedation; this had responded to a brief period of jaw thrust and sedation adjustment.

Post operative neurological impairment was observed in two patients who developed transient hemiparesis. One of these patients had a pre-existing weakness before surgery and developed further weakness postoperatively; the weakness returned to the preoperative level two days following surgery. Hemiparesis resolved in all patients within 3 weeks.

Conclusions and recommendations

We feel that we have achieved a method of providing safe and effective operative conditions for such group of patients with compromised health, while allowing for maximal tumor resection with minimal impairment of neurological functions.

In our experience, the advantages of avoiding the risk of general anaesthesia while having the chance of safe and maximum tumour resection in this selected group of patients make it sound to say that most medical conditions can be considered as indication for awake craniotomy. Still, the balance between the benefits and possible risks should be considered in each case.

A controlled randomised group of patients undergoing craniotomy under general anaesthesia would strengthen the findings derived from this study. Large scale studies are recommended to prove that most medical conditions can be considered only a relative contraindication for awake craniotomy.

1986

References

- Sahjpaul, RL. Awakecraniotomy: controversies, indications and techniques in the surgical treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000; 27l suppl. 1): S55-63.

- Blanshard, HJ., Chung, F., Manninen, PH., Taylor, MD., Bernstein, M. Awake craniotomy for removal of intracranial tumor: considerations for early discharge. Anesth Analg. 2001; 92: 89-94

- Taylor, MD., Bernstein, M. Awake craniotomy with brain mapping as the routine surgical approach to treating patients with supratentorialintraaxial tumors a prospective trial of 200 cases. J Neurosurg. 1999; 90: 35-41

- Huncke, K., Van de Wiele, B., Fried, I., Rubinstein, EH. The aslee– awake–asleep anesthetic technique for intraoperative language mapping. Neurosurgery 1998; 42: 1312-6.

- Tongier, WK., Joshi, GP., Landers, DF., Mickey, B Use of the laryngeal mask airway during awake craniotomy for tumor resection. J Clin Anesth. 2000; 12: 592-4.

- Gignac, E., Manninen, PH., Gelb, AW. Comparison of fentanyl, sufentanil and alfentanil during awake craniotomy for epilepsy. Can J Anaesth. 1993; 40: 421-4.

- Hans, P., Bonhomme, V., Born, Maertens de Noordhoudt, A., Brichant, JF., Dewandre, PY. Target-controlled infusion of propofol and remifentanil combined with bispectral index monitoring for awake craniotomy Anaesthesia 2000; 55: 255-9.

- Sacko, O., Lauwers-Cances, V., Brauge, D., Sesay, M., Brenner, A., Roux, F., Awake craniotomy vs surgery under general anesthesia for resection of supratentorial lesions. Neurosurgey. 2011; 68 (5): 1192-8.

- Taylor, MD., Bernstein, M. Awake craniotomy with brain mapping as the routine surgical approach to treating patients with supratentorial intra-axial tumors: a prospective trial of 200 cases. J Neurosurg 1999; 90: 35-41.

- A. Sarang, J. Dinsmore, Anaesthesia for awake craniotomy—evolution of a technique that facilitates awake neurological testing, Br. J. Anaesth. (2003) 90 (2): 161-165.

- Herrick, IA., Craen, RA., Gelb,W, . et al. Propofol sedation during awake craniotomy for seizures: patient-controlled administration versus neurolept analgesi. Anesth Analg. 1997; 84: 185–-91.2. - Weiss, FR., Schwartz, R. Anaesthesia for awake craniotomy. Can J Anaesth. 1993; 40: 103.