Keywords

Canned fish, Chemical composition, Trace metals, Free amino acids, Cholesterol, Taurine

Introduction

In a recent paper (Aydin 2011) about fish and fishery products consumption in Turkey it was demonstrated that 32% of Turkish households consumed such products when taking the average of the last 12 years while the remaining 68% did not consume fish at all.

Another study (Erdogan et al. 2011) demon-strated that canned seafood was most preferred (37.6%) followed by frozen seafood products (26.8%).

This underlines the importance to have a good and comprehensive knowledge about the nutri-tional properties and present risks in canned products processed in Turkey from Turkish raw materials. In canned products a number of nutri-tionally important components as amino acids, taurine, selenium, and lipids are present but also the occurrence of heavy metals as cadmium and lead are reported. The concentrations of all toxic elements and essential elements in selected prod-ucts like canned anchovy or tuna fillets were found to be high and often exceeded legal limits set by health authorities (Celik et al. 2007). Therefore the authors concluded that these prod-ucts must be monitored more often. Data about other components such as cholesterol content, phosphorous, alkali elements and heavy metals as zinc and copper are almost lacking.

Also in the raw fish material from Turkish waters which can be used for canning elevated concentrations of heavy metals have been report-ed (Celik et al. 2004; Dalman et al. 2006; Ersoy et al. 2010; Mendil et al. 2010; Mol et al. 2012; Tuzen 2009; Uluozlu et al. 2007; Yildirim et al. 2009; Yilmaz et al. 2010).

In the case of canned fish production a storage process (chilling or freezing) is needed for stor-ing the raw material prior to canning. A heating step (cooking, smoking, and frying) is normally applied for reducing water content and inactivat-ing endogenous enzyme activity. A rigorous thermal treatment (sterilization) is undertaken to inactivate micro-organisms and to guarantee a prolonged shelf life. Labile and essential nutri-ents (proteins, vitamins, lipids, minerals) present in the raw fish are exposed to different pro-cessing conditions that can reduce the nutritional and sensory values of the final product (Aubourg 2001).

Amino acids are not only components of all peptides and proteins but also precursor com-pounds relevant to food flavour, taste and colour-ing (Belitz et al. 2009). The content of free amino acids in food and their losses due to industrial processing are also interesting because of nutri-tional aspects. Very remarkable is the content of taurine in fish. Taurine is a conditional essential free amino acid with several health-beneficial ef-fects (Undeland 2009).

In this investigation both, nutritional positive components as well as potentially harmful ele-ments as heavy metals have been analysed to give a good overview about the nutritional value of the canned fish products from Turkey.

Materials and Methods

Samples and Sample Preparation

Commercial brands of canned fish products were purchased in retail stores in Izmir, Turkey. Products chosen are typically consumed in Tur-key. The samples analysed consisted of whole anchovy in oil (Dardanel Hamsi sosyete), headed sardine in oil (Dardanel sardalya), mackerel fillet in own juice (Migros Uskumru), bonito fillet in own juice (Migros Palamut), and trout fillet in tomato sauce (Migros Alabalik), 5 cans each.

The chemical analyses were performed in Hamburg, Germany. Convenient aliquots or pooled samples (depending on the amount of ma-terial) of the dripped fish part were homogenized in a knife mill and taken for analyses.

Proximate Analyses

Moisture was determined gravimetrically in an aliquot of the homogenate after drying for 12h in an oven at 105 °C until weight was constant. Percent raw protein was calculated by multiply-ing nitrogen (%) by 6.25 (nitrogen was measured by Dumas using a LECO TruSpecN (LECO in-struments GmbH, Mönchengladbach, Germany)) (AOAC 2005). The lipid content was analyzed by a modified method of Smedes (1999) (Karl et al. 2012).

Ash content was determined according to An-tonacopoulus (1973). The amount of salt was obtained by titration with 0.1 N AgNO3 so-lution after protein precipitation with Carrez I and Carrez II (Karl et al. 2002).

Cholesterol Content

Cholesterol was analyzed according to the method and quantification based on the experi-mental procedure of Naemmi et al (1995) as modified by Oehlenschläger (2006).

Total Phosphorus Content

The total phosphorus content was determined photometrically in the nitric acid extract of the ash according to a modified official German method of the foodstuffs and animal feed code to measure phosphorus in meat (§ 64 LFGB 2008).

Free Amino Acid Composition

For sample deproteinization 10 g fish sample were homogenized with 90 mL 6 % perchloric acid (w/w) and subsequently filtrated. HPLC de-termination of the free amino acids (17, including taurine) was performed in the diluted extracts (1:10 up to 1:200). After precolumn derivatiza-tion with o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) according to a modified method of Antoine and co-workers (1999), the amino acids were separated on a re-versed-phase column by a gradient and then quantified by fluorescence detection using the in-ternal standard method with 2-aminobutyric acid.

Mineral Element Analysis

The homogenised fish samples (1.6 – 2.0 mg wet weight) were digested in a mixture of 4 mL 65% nitric acid suprapur and 1 mL 30% hydro-gen peroxide in closed tetrafluormethaxil quarz vessels of a temperature-time programmed Mile-stone ultraCLAVE III (Milestone SRL, Sorisole, Italy) digestion system.

Na, K, Ca and Mg were measured by flame AAS (contrAA® 700 high-resolution continuum source atomic absorption spectrometer with air-acetylene flame equipped with an autosampler, Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany).

Selenium Measurements

The samples were prepared as described above. Selenium was analyzed by the continuous flow hydride system of the contrAA® 700. For the reduction of Se (VI) to Se (IV) prior to the hydride generation 6 M HCl was added to an ali-quot of the sample solution (1:1 v/v) and heated in a water bath for 30 min at 90 °C.

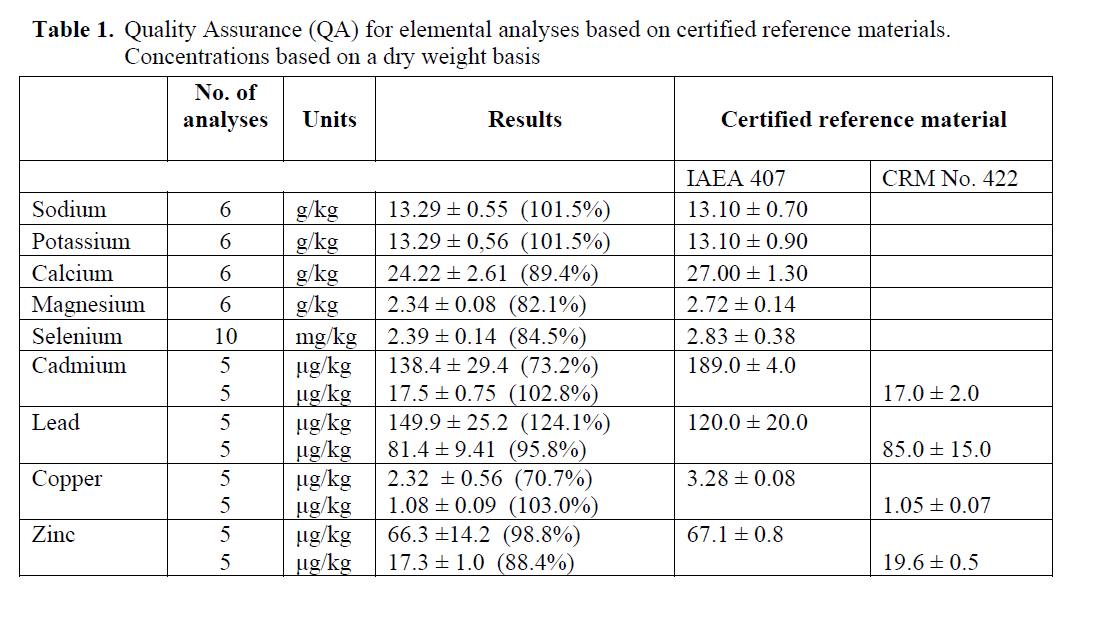

Quality Assurance of AAS Determination

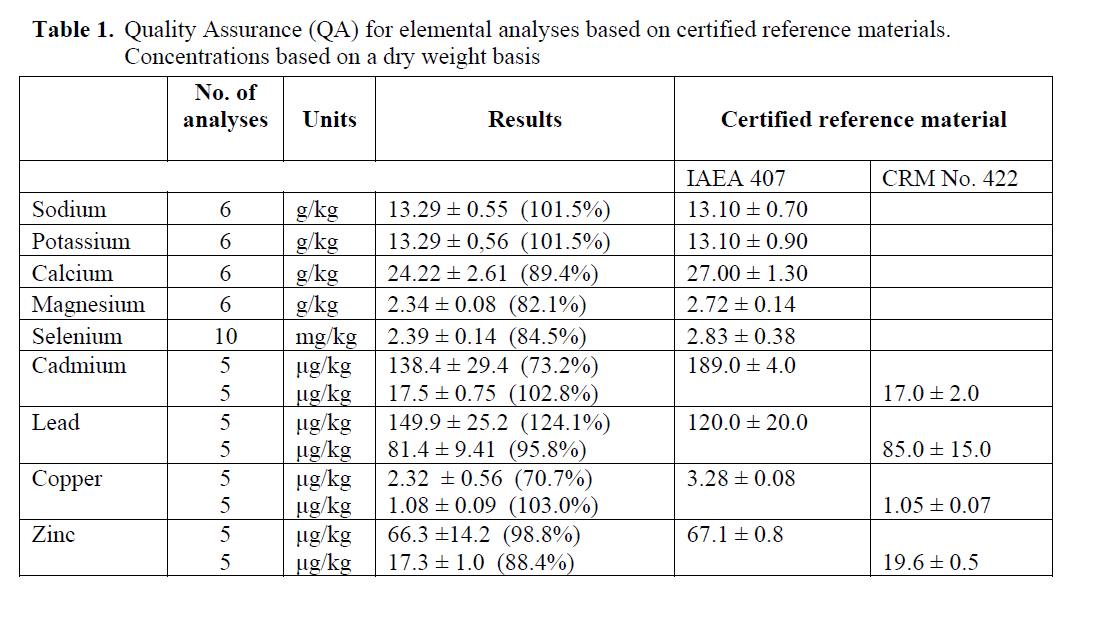

The commercial reference material IAEA-407 of the International Atomic Energy Agency was used to validate the analytical methods and as quality control. The mean values obtained for an-alytical recovery were 101% (Na), 100% (K), 89% (Ca), 82% (Mg) and 83% (Se) (Table 1).

Table 1: Quality Assurance (QA) for elemental analyses based on certified reference materials. Concentrations based on a dry weight basis.

Heavy Metals

All samples were lyophilised in a Finn-Aqua Lyovac GT 2 freeze dryer (GEA Process Engi-neering Inc., Columbia, U.S.), milled in a ball mill made from agate and finally decomposed in an oxygen plasma ashing chamber. Differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry (746 VA Trace Analyser, Metrohm, Switzerland) was used for the determination under the same experi-mental conditions, as described elsewhere in de-tail (Celik et al 2007). For analytical quality con-trol the recommendations given in the guidelines of NMKL (2011) are followed whenever possi-ble. The accuracy of the concentrations determined in this study was verified by measure-ments of certified reference materials. Results given in Table 1 show that all elements were de-termined with good accuracy.

Statistical Evaluation

One-way ANOVA (Tukey-Test) was applied for statistical analysis (SigmaStat version 3.5, Systat software Inc., San Jose, U.S.).

Results and Discussion

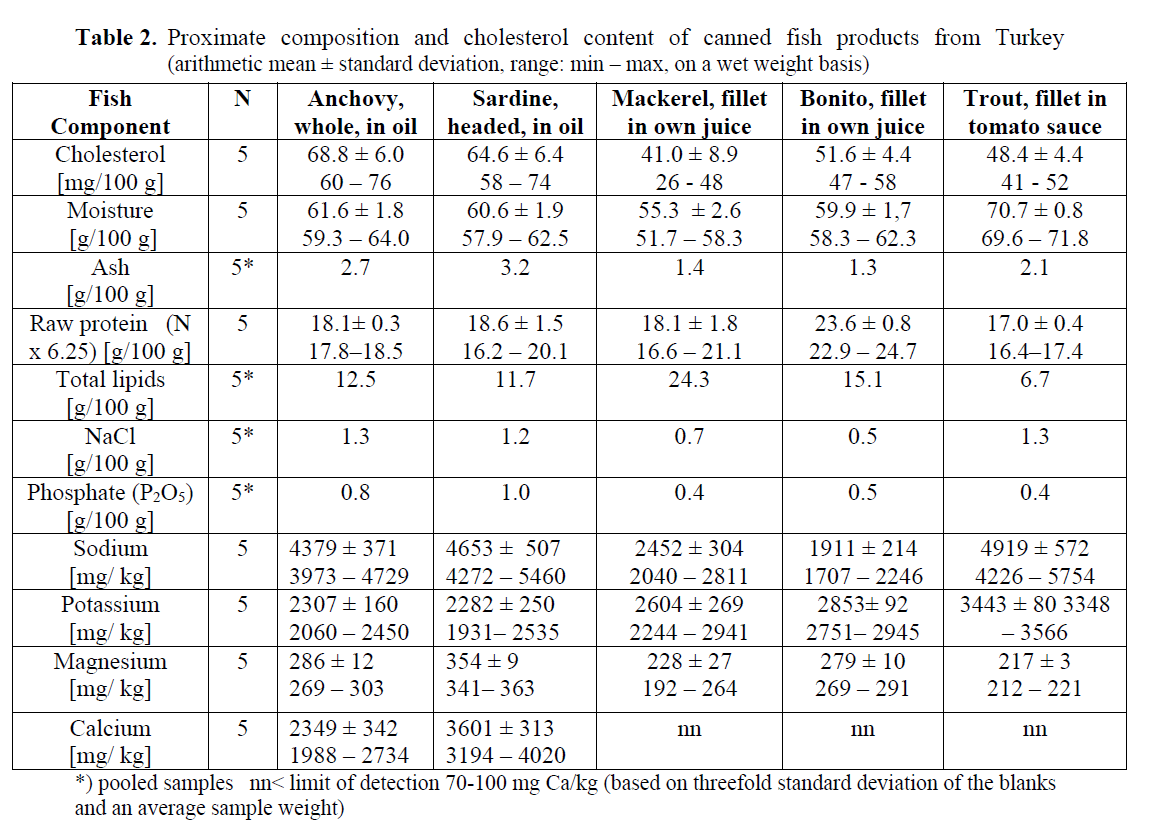

Proximate Composition and Cholesterol Content

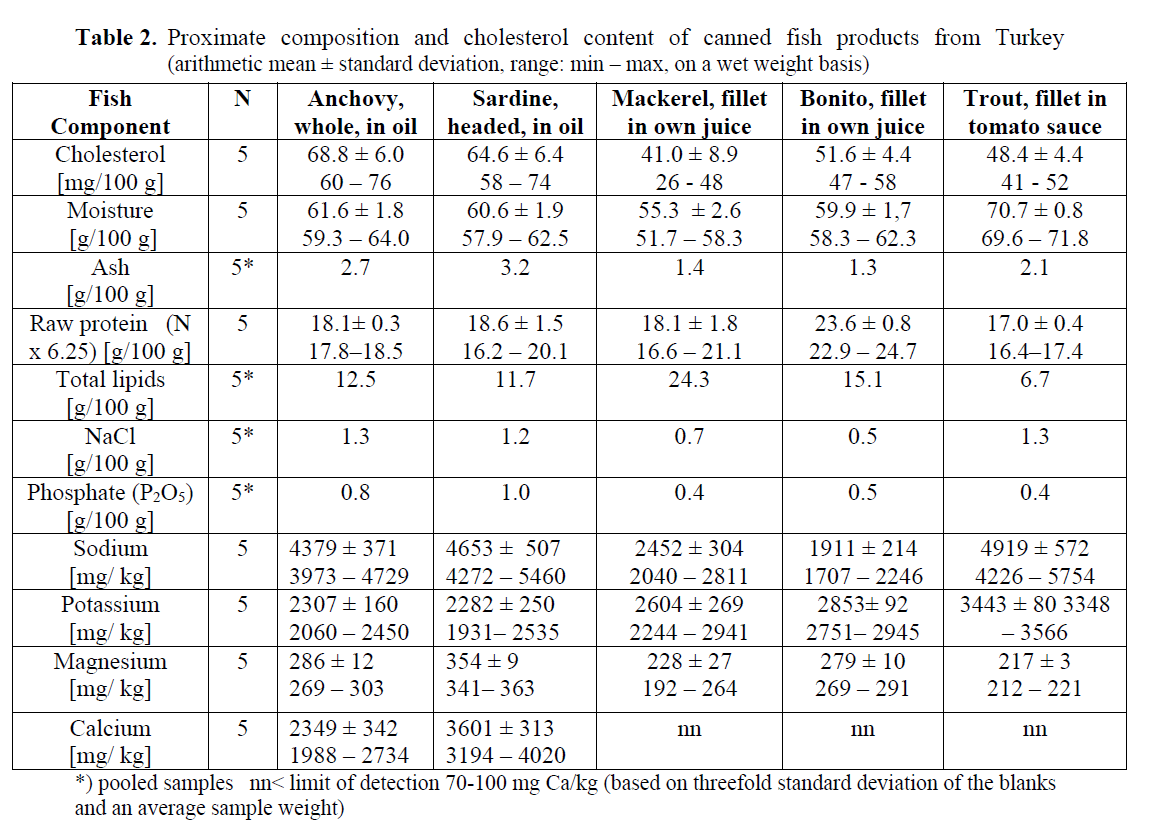

The basic nutritional ingredients show that the canned fish products contained considerable amounts of raw protein. The highest average raw protein content was measured in bonito (23.6%) and the lowest in trout fillets (17.0%) (Table 2). The average fat content ranged between 6.7% (trout) and 24.3% (mackerel). Fish lipids are a very good source of essential unsaturated fatty acids. The consumption of such products can help to cover the daily amounts of valuable long chain unsaturated omega-3 fatty acids recom-mended for the prevention of heart diseases.

Table 2: Proximate composition and cholesterol content of canned fish products from Turkey (arithmetic mean ± standard deviation, range: min – max, on a wet weight basis)

Fish products are usually not a considerable source for cholesterol via food intake. In raw fish from the Northeast Atlantic an average of approx. 40 mg/100 g was determined. Fish species from temperate areas can have slightly higher values (Oehlenschläger 2006). Levels between 41 and 69 mg cholesterol/100 g in the canned fish spe-cies were in the low range and confirm that the cholesterol content does not correlate with the respective lipid values. It could also be confirmed that there is no increase of cholesterol in the fish caused by other ingredients.

Mineral Element Analysis

Marine food serves as a moderate to good source of minerals. Fish flesh generally contains high amounts of potassium (around 0.35 g/100g and low amounts of sodium (around 0.04 g/100g) (Holland et al 1993; Oehlenschläger 1997; Oeh-lenschläger et al 2009). In the samples investigat-ed the natural amounts of sodium have been in-creased by the addition of salt to contents be-tween 0.5 and 1.3 gNaCl/100g while potassium remained at its natural content (0.228 -0.344 g/100g, Table 2).

The level of magnesium in the raw and bone-less muscle is higher (average 0.025 g/100g) than the calcium content which is confirmed by the results of the canned fillets in Table 2. Only fish eaten with bones like anchovy and sardines is an excellent source for calcium (Holland et al. 1993), in boneless canned fish the calcium con-tent was below the limit of detection.

The phosphorous content is somewhat higher in canned fish, where the bones are in and lower in boneless fillets. From the data in Table 2 it is evident that all phosphorous present is natural (0.4–1.0 g P2O5/100g) and no phosphate based additives have been added during production.

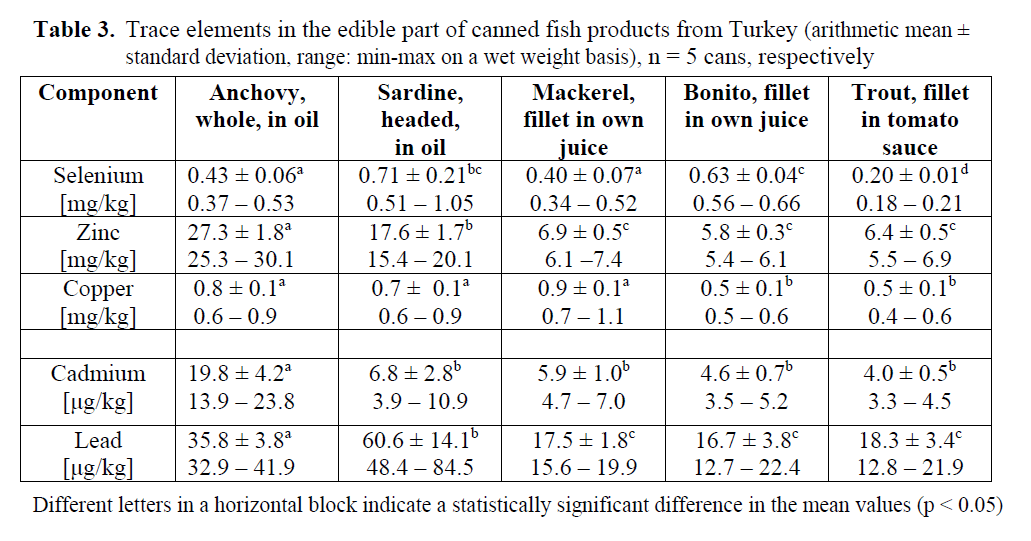

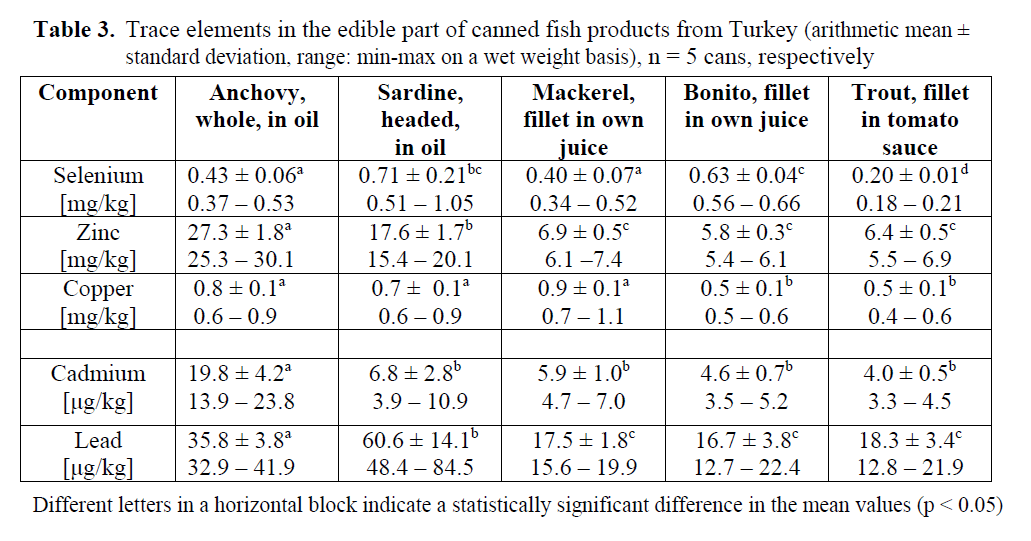

Particularly worth mentioning is selenium as an essential micronutrient which plays a vital role in human health. Fish is an important and highly bio-available source of dietary selenium. The content of this element can vary considerably be-tween specimens, but is on average quite constant between species. Marine fish from the Northeast Atlantic waters contains between 0.3 and 0.6 mg selenium/kg, values for freshwater fish can be somewhat lower (Oehlenschläger 2006). The results of this study (Table 3) confirm these find-ings. The recommended daily allowances of sele-nium of 0.03-0.07 mg of the German Nutrition Society (2008) are already covered by the con-sumption of about 100 g of the analysed fish spe-cies.

Table 3: Trace elements in the edible part of canned fish products from Turkey (arithmetic mean ± standard deviation, range: min-max on a wet weight basis), n = 5 cans, respectively

The results for the element traces are present-ed in Table 3. All cadmium concentrations found were well below the legal Turkish Food Codex and the strictest EU limits (100 μg/kg (Anony-mous 2008) and 50 μg/kg wet weight, respective-ly). The highest amount 20 μg/kg was present in anchovy; the other 4 samples contained only 4-7 μg/kg. The values for anchovy were low com-pared with literature data that reported for fresh anchovy 650 μg/kg (Uluozlu et al. 2007) and 270 μg/kg (Tuzen 2009). For canned anchovy Tuzen and Soylak (2007) and Celik et al. (2007) pub-lished 120 μg/kg and 92 μg/kg, respectively. In contrast, Mol (2011a) found lower cadmium con-tents in canned anchovy ranging between 1 and 19 μg/kg which are in good agreement with the figures reported in this paper. For canned sardine and tuna 190 μg/kg and 80 μg/kg, respectively, were analyzed (Tuzen et al. 2007). Similar and comparable low cadmium concentrations of 10-20 μg/kg in canned tuna were published in 2011 by Mol (2011b). However, in a recent study about trace elements in vacuum packed smoked Turkish rainbow trout, a cadmium content of 10 μg/kg was found (Sireli et al. 2006). Galitsopou-lou (2012) explained a certain increase in cadmi-um content of anchovies and sardines after can-ning compared to the raw material used by the water reduction process prior to canning.

The Turkish Food Codex permits 300 μg/kg as maximum lead level in fish (Anonymous 2002). The lead contents were also all below this limit, ranging from 17 μg/kg in bonito fillet to 61 μg/kg in sardine. 90 μg Pb/kg have been re-ported by Tuzen (2009) in canned sardine which is close to the amount found in this investigation, but the author found a much higher lead content in canned anchovy (400 μg/kg). Mol (2011a) re-ported in canned anchovies a lead concentration of 188 μg/kg which exceeds the results of this in-vestigation by a factor of 5. In canned tuna a lead content ranging between 90 and 450 μg/kg was reported by Mol (2011b). The significantly high-er lead concentration in canned products contain-ing bones can be explained by the fact that lead can be accumulated in bone tissue (Oehlenschlä-ger 2002).

All samples contained zinc ranging from a low content in mackerel (6.9 mg/kg), bonito (5.8 mg/kg) and trout (6.4 mg/kg) to a higher content in anchovy and sardine (27.3 mg/kg and 17.6 mg/kg). This is in good agreement with oth-er findings where 34.0 mg/kg have been found in canned anchovy and 7.5 mg/kg in canned sardine (Tuzen 2009). In canned tuna a zinc concentra-tion between 8.2 and 12.4 mg/kg was given by Mol (2011b).

Copper concentrations were found to be low around 0.5 mg/kg. These values were lower than those reported by Tuzen (2009) (1.8 mg/kg for anchovy and 2 mg/kg for sardine), but in good agreement with the copper content reported for canned tuna (0.45-0.58 mg/kg) by Mol (2011b).

Free Amino Acids

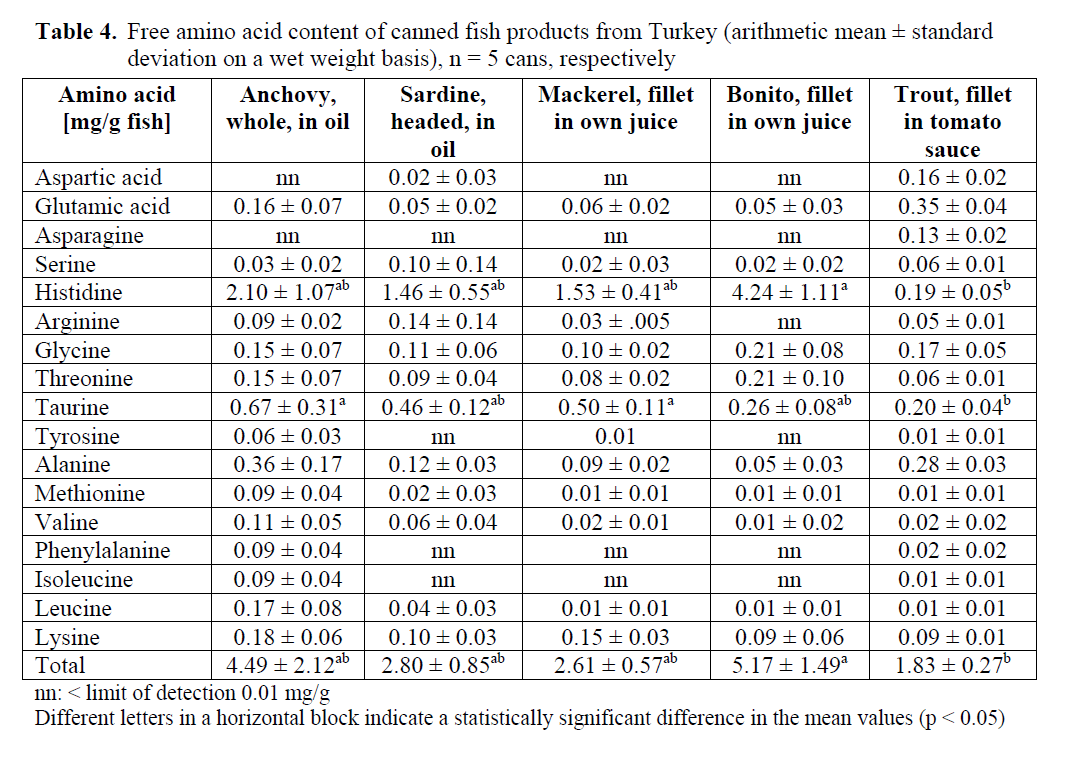

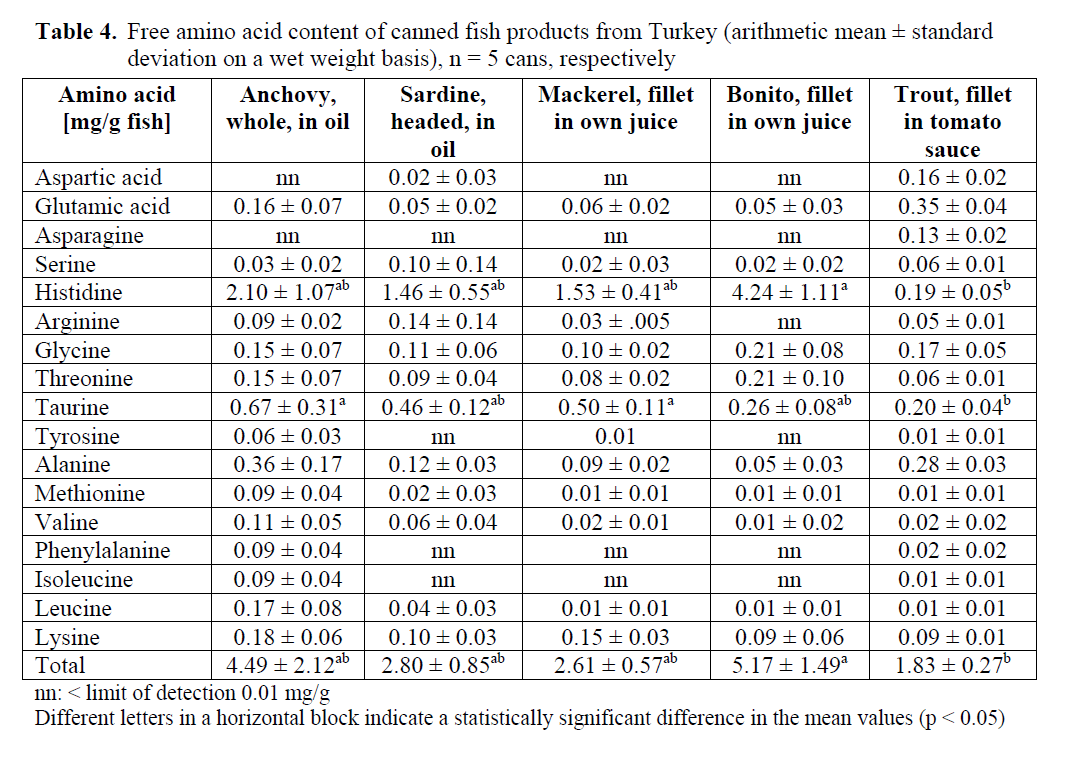

The total content of free amino acids varied clearly among species and between single cans of the same product (Table 4). In cans containing marine fish species individual amino acids such as asparagine, aspartic acid, phenylalanine and isoleucine were found only in minimal quantities. In trout products the levels of asparagine, aspartic acid and particularly glutamic acid were much higher.

Table 4: Free amino acid content of canned fish products from Turkey (arithmetic mean ± standard deviation on a wet weight basis), n = 5 cans, respectively

In all tested fish cans the high levels of taurine became obvious. Taurine is an amino sulfonic ac-id that is never incorporated into proteins, but is present in free form only in animal tissues. Hu-mans are limited capable of biosynthesising tau-rine, but it is of importance for many physiologi-cal processes. For example taurine is beneficial for cardiovascular health, reduces blood choles-terol values, and has antioxidant properties (Un-deland 2009). Taurine is a heat stable, water sol-uble compound of low molecular weight. It is a known fact that during processing of fish the concentration of taurine decreased mainly as a result of leaching (Dragnes et al. 2009; Larsen et al. 2010). Because the raw fish was not analysed, a calculation of the loss of taurine and other free amino acids during processing was not possible.

The taurine content in the fish products (ex-cept for trout) was only exceeded by the histidine content. Especially marine fish contained high amounts exceeding the limit of the analytical de-termination procedure. The actual levels are therefore higher. Some free amino acids like his-tidine or lysine can result in the rapid formation of biogenic amines during microbial spoilage of fish.

Conclusions

The canned fish products investigated can be described as products rich in protein and fat with low cholesterol content. They are a good source of magnesium, zinc and selenium and those con-taining bones also of phosphorous. No phos-phates were added as additives. The samples con-tained high amounts of taurine and histidine. The contents of the heavy metals lead and cadmium were below legal Turkish limits. These canned products produced and marketed in Turkey are from a nutritional point of view recommended to be consumed.

Acknowledgement

The skilful technical assistance of S. Blechner (elements), I. Delgado and H.-J. Knaack (proxi-mate composition), T. Schmidt (amino acids), and I. Wilhelms (cholesterol) is gratefully acknowledged.

393

References

- Anonymous, (2002). Regulation of setting maxi-mum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Official Gazette, Issn: 24908

- nAnonymous, (2008). Regulation of setting maxi-mum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Official Gazette, Issn: 26879

- nAntoine, F.R., Wei, C.I., Littell, R.C., Marshall, M.R., (1999). HPLC method for analysis of free amino acids in fish using o-phthaldialdehyde precolumn derivatization, Journal of Agricultural and Food Che-mistry, 47: 5100-5107. doi: 10.1021/jf990032+

- nAntonacopoulos, N., (1973). Lebensmittelche-misch-rechtliche Untersuchung und Beurtei-lung von Fischen und Fischerzeugnissen. In: W. Ludorff & V. Meyer (Eds.): Fische und Fischerzeugnisse (p. 219). Berlin/ Hamburg, Germany: Paul Parey Verlag

- nAOAC, (2005). Method #968.06. Official meth-ods of analysis of AOAC International, 18th Edition. AOAC International, Gaithersburg, U.S

- nAubourg, S.P., (2001). Review: Loss of quality during the manufacture of canned fish prod-ucts, Food Science and Technology Interna-tional, 7: 199-215. doi: 10.1106/4H8U-9GAD-VMG0-3GLR

- nAydin, H., Dilek, M.K., Aydin, K. (2011). Trends in fish and fishery products consumption in Turkey, Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 11: 499-506. doi: 10.4194/trjfas.2011.0318

- nBelitz, H.D., Grosch W., Schieberle P., (2009). Amino acids, peptides, proteins. In: Food Chemistry (4th revised and extended Edi-tion) (pp. 8-89). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germa-ny: Springer Verlag

- nCelik, U., Oehlenschläger, J., (2007). High con-tents of cadmium, lead, zinc and copper in popular fishery products sold in Turkish su-permarkets, Food Control, 18: 258-261. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2005.10.004

- nCelik, U., Cakli, S., Oehlenschläger, J., (2004). Determination of the lead and cadmium bur-den in some north eastern Atlantic and Med-iterranean fish species by DPSAV, Euro-pean Food Research and Technology, 218: 298–305. doi: 10.1007/s00217-003-0840-y

- nDalman Ö., Demirak A., Balci A., (2006). De-termination of heavy metals (Cd, Pb) and trace elements (Cu, Zn) in sediments and fish of the Southeastern Aegean Sea (Tur-key) by atomic absorption spectrometry, Food Chemistry, 95: 157-162. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.009

- nDragnes, B.T., Larsen, R., Ernstsen, M.H., Mæh-re, H., Elvevoll, E.O., (2009). Impact of processing on the taurine content in pro-cessed seafood and their corresponding un-processed raw materials, International Jour-nal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 60: 143-152. doi: 10.1080/09637480701621654

- nErdogan, B.E., Mol, S., Cosansu, S., (2011). Fac-tors influencing the consumption of seafood in Istanbul, Turkey, Turkish Journal of Fis-heries and Aquatic Sciences, 11: 631-639. doi: 10.4194/1303-2712-v11_4_18

- nErsoy B., Celik U., (2010). The essential and tox-ic elements in tissues of six commercial de-mersal fish from Eastern Mediterranean Sea, Food and Chemical Toxicology, 48: 1377-1383

- ndoi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.03.004Anonymous, (2002). Regulation of setting maxi-mum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Official Gazette, Issn: 24908

- nAnonymous, (2008). Regulation of setting maxi-mum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Official Gazette, Issn: 26879

- nAntoine, F.R., Wei, C.I., Littell, R.C., Marshall, M.R., (1999). HPLC method for analysis of free amino acids in fish using o-phthaldialdehyde precolumn derivatization, Journal of Agricultural and Food Che-mistry, 47: 5100-5107. doi: 10.1021/jf990032+

- nAntonacopoulos, N., (1973). Lebensmittelche-misch-rechtliche Untersuchung und Beurtei-lung von Fischen und Fischerzeugnissen. In: W. Ludorff & V. Meyer (Eds.): Fische und Fischerzeugnisse (p. 219). Berlin/ Hamburg, Germany: Paul Parey Verlag

- nAOAC, (2005). Method #968.06. Official meth-ods of analysis of AOAC International, 18th Edition. AOAC International, Gaithersburg, U.S

- nAubourg, S.P., (2001). Review: Loss of quality during the manufacture of canned fish prod-ucts, Food Science and Technology Interna-tional, 7: 199-215. doi: 10.1106/4H8U-9GAD-VMG0-3GLR

- nAydin, H., Dilek, M.K., Aydin, K. (2011). Trends in fish and fishery products consumption in Turkey, Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 11: 499-506. doi: 10.4194/trjfas.2011.0318

- nBelitz, H.D., Grosch W., Schieberle P., (2009). Amino acids, peptides, proteins. In: Food Chemistry (4th revised and extended Edi-tion) (pp. 8-89). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germa-ny: Springer Verlag

- nCelik, U., Oehlenschläger, J., (2007). High con-tents of cadmium, lead, zinc and copper in popular fishery products sold in Turkish su-permarkets, Food Control, 18: 258-261

- nCelik, U., Cakli, S., Oehlenschläger, J., (2004). Determination of the lead and cadmium bur-den in some north eastern Atlantic and Med-iterranean fish species by DPSAV, Euro-pean Food Research and Technology, 218: 298–305. doi: 10.1007/s00217-003-0840-y

- nDalman Ö., Demirak A., Balci A., (2006). De-termination of heavy metals (Cd, Pb) and trace elements (Cu, Zn) in sediments and fish of the Southeastern Aegean Sea (Tur-key) by atomic absorption spectrometry, Food Chemistry, 95: 157-162. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.009

- nDragnes, B.T., Larsen, R., Ernstsen, M.H., Mæh-re, H., Elvevoll, E.O., (2009). Impact of processing on the taurine content in pro-cessed seafood and their corresponding un-processed raw materials, International Jour-nal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 60: 143-152. doi: 10.1080/09637480701621654

- nErdogan, B.E., Mol, S., Cosansu, S., (2011). Fac-tors influencing the consumption of seafood in Istanbul, Turkey, Turkish Journal of Fis-heries and Aquatic Sciences, 11: 631-639. doi: 10.4194/1303-2712-v11_4_18

- nErsoy B., Celik U., (2010). The essential and tox-ic elements in tissues of six commercial de-mersal fish from Eastern Mediterranean Sea, Food and Chemical Toxicology, 48: 1377-1383. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.03.004

- nGalitsopoulou, A., Georgantelis D., Kontominas M., (2012). The influence of industrial-scale canning on cadmium and lead levels in sar-dines and anchovies from commercial fish-ing centres of the Mediterranean Sea, Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, 5: 75-81. doi: 10.1080/19393210.2012.658582

- nGerman Nutrition Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung) (2008). The reference values for nutrient intake (in German). Retrieved March 15, 2013 from: https://www.dge.de

- nHolland, B., Brown, J., Buss, D.H., (1993). In: Fish and Fish Products. 3. Supplement to the 5th Edition of McCance and Widdowson´s “The Composition of Foods”. The Royal Society of Chemistry. London, UK.: Clays LTD

- nKarl, H., Äkesson, G., Etienne, M., Huidobro A., Luten, J., Mendes, R., Tejada, M., Oeh-lenschläger, J., (2002). WEFTA interlabora-tory comparison on salt determination in fishery products, Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology, 11: 215-228. doi: 10.1300/J030v11n03_17

- nKarl, H., Bekaert, K., Berge, J-P., Cadun, A., Duflos, G., Oehlenschläger, J., Poli, B., Tejada, M., Testi, S., Timm-Heinrich, M., (2012). WEFTA interlaboratory comparison on total lipid determination in fishery prod-ucts using the Smedes method, Journal of AOAC International, 95: 1-5. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.11-041

- nLarsen, R., Mierke-Klemeyer, S., Mæhre, H., Elvevoll, E.O., Bandarra, N.M., Cordeiro, A.R., Nunes, M.L., Schram, E., Luten, J., Oehlenschläger, J., (2010). Retention of health beneficial components during hot- and cold-smoking of African catfish (Clari-as gariepinus) fillets, Archiv Lebensmittelh-ygiene, 61: 31-35

- nLFGB (2008) Amtliche Sammlung von Unter-suchungsverfahren nach §64 LFGB. Bes-timmung des Gesamtphosphorgehaltes in Fleisch und Fleischerzeugnissen, Photomet-risches Verfahren. 06.00/9. Retrieved March 15, 2013 from: https://www.methodensammlung-bvl.de

- nMendil, D., Demirci, Z., Tuzen, M., Soylak, M., (2010). Seasonal investigation of trace ele-ment contents in commercially valuable fish species from the Black sea, Turkey, Food and Chemical Toxicology, 48: 865-870. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.023

- nMol, S., (2011a). Determination of trace metals in canned anchovies and canned rainbow trouts, Food and Chemical Toxicology, 49: 348-351. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.11.005

- nMol, S., (2011b). Levels of selected trace metals in canned tuna fish produced in Turkey, Jo-urnal of Food Composition and Analysis, 24: 66-69. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2010.04.009

- nMol, S., Ozden, O., Saadet, K., (2012). Levels of selected metals in albacore (Thunnus ala-lunga, Bonnaterre, 1778) from Eastern Med-iterranean, Journal of Aquatic Food Product Technology, 21: 111-117. doi: 10.1080/10498850.2011.586489

- nNaemmi, E.D., Ahmad, N., Al-sharrah T.K., Behbahani M., (1995). Rapid and simple method for determination of cholesterol in processed food, Journal of AOAC Internati-onal, 78: 1522–1525

- nNMKL (Nordic Committee on Food Analysis), (2011). NMKL Protocol No. 5, Analytical Quality Control – Guidelines for the publi-cation of analytical results of chemical anal-yses in foodstuffs, 23p. + 1 Annex. Retrie-ved March 15, 2013 from: https://www.nmkl.org

- nOehlenschläger, J., (1995). Selengehalte im See-fischmuskel. In: Ernährungsphysiologische Eigenschaften von Lebensmitteln. Schrif-tenreihe des Bundesministeriums für Ernäh-rung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten. An-gewandte Wissenschaft, Heft 445 (pp.86-91). Münster, Germany: Landwirtschaftsver-lag

- nOehlenschläger, J., (1997). Marine fish - a source for essential elements? In: J.B. Luten et al. (Eds.), Development in food science 38. Sea-food from producer to consumer, integrated approach to quality (pp. 641-651). Amster-dam, The Netherlands: Elsevier

- nOehlenschläger, J., (1999). Gaschromatograp-hische Bestimmung des Gesamtcholesterolgehaltes im verzehrbaren Anteil (Filet) von Meeresfischen und Garnelen, Lebensmittel-chemie, 53: 86

- nOehlenschläger, J., (2002). Identifying heavy me-tals in fish. In: H.A. Bremner (Ed.), Safety and quality issues in fish processing (pp. 95-113). Cambridge, UK.: Woodhead. doi: 10.1533/9781855736788.1.95

- nOehlenschläger, J., (2006). Cholesterol content in seafood, data from the last decade: a review. In: J.B. Luten et al. (Eds.), Seafood research from fish to dish: quality, safety and pro-cessing of wild and farmed fish (pp. 41-58). Wageningen, The Netherlands. Academic Publishers

- nOehlenschläger, J., Rehbein, H., (2009). Basic facts and figures. In: H. Rehbein & J. Oeh-lenschläger (Eds.), Fishery Products – Qual-ity, safety and authenticity (pp. 1-18). Ox-ford, UK: Wiley- Blackwell

- nÖzogul, Y., Özogul, F., Alagoz, S., (2007). Fatty acid profiles and fat contents of commercial-ly important seawater and freshwater fish species of Turkey: A comparative study, Food Chemistry, 103: 217-223. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.009

- nSireli, U.T., Göncüoglu, M., Yildirim, Y., Gücü-koglu, A., Çakmak, Ö., (2006). Assessment of heavy metals (cadmium and lead) in vac-uum packaged smoked fish species (macke-rel, Salmo salar and Oncorhynhus mykiss) marketed in Ankara (Turkey), Ege Universi-ty Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences, 23: 353–356

- nSmedes, F., (1999). Determination of total lipid using non-chlorinated solvents, Analyst, 124: 1711-1718. doi: 10.1039/A905904K

- nTuzen, M., (2009). Toxic and essential trace ele-mental contents in fish species from the Black Sea, Turkey, Food and Chemical Toxicology, 47: 1785-1790. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.04.029

- nTuzen, M., Soylak, M., (2007). Determination of trace metals in canned fish marketed in Tur-key, Food Chemistry, 101: 1378-1382. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.03.044

- nUluozlu, O.D., Tuzen, M., Mendil, D., Soylak, M., (2007). Trace metal content in nine spe-cies of fish from Black and Aegean Seas, Turkey, Food Chemistry, 104: 835-840. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.003

- nUndeland, I., (2009). Selected amino acids in fish. In; Luten, J.B. (Ed.), Marine functional food (pp. 43-47). Wageningen, The Nether-lands: Academic Publishers

- nYildirim, Y., Gonulalan, Z., Narin, I., Soylak, M., (2009). Evaluation of trace heavy metal lev-els of some fish species sold at retail in Kay-seri, Turkey, Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 149: 223-228. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0196-7

- nYilmaz, A.B., Sangün, M.K., Yaglioglu, D., Tu-ran, C., (2010). Metals (major, essential to non-essential) composition of the different tissues of three demersal fish species from Iskenderun Bay, Turkey, Food Chemistry, 123: 410-415. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.04.057