Research Article - (2022) Volume 16, Issue 5

Chronotype Depression And Physical Activity: A Relationship To Be Studied?

Lais Tonello,

Lais Tonello and

Michael Jackson Oliveira De Andrade

Postgraduate Program on Physical Education, Catholic University of Brasilia, Brazil

Departament of Physical Education, Gurupi University UnirG, Tocantins, Brazil

Departament of Psychology Laboratory of Neuroscience, Chronobiology and Sleep Psychology State University of Minas Gerais, Unidad Divinopolis, Brazil

*Correspondence:

Elaine Vieira, Postgraduate Program on Physical Education, Catholic University of Brasilia,

Brazil,

Tel: 77403-090,

Email:

Received: 17-May-2022, Manuscript No. Iphsj-22-12785;

Editor assigned: 19-May-2022, Pre QC No. PreQC No. Iphsj-22-12785;

Reviewed: 03-Jun-2022, QC No. QC No. Iphsj-22-12785;

Revised: 08-May-2022, Manuscript No. Iphsj-22-12785(R);

Published:

16-Jun-2022, DOI: 10.36648/1791-809X.16.5.944

Abstract

Introductionː Preferences for certain times of day to perform daily activities have been

the focus of several investigations. Individuals with evening preference exhibit higher

scores for depressive symptoms and less involvement in physical activities compared

to morning and intermediate chrono types. On the other hand, physical activity is an

intervention that has shown great promise in alleviating symptoms of Major depressive

disorder.

Evidence Acquisitionː This study aimed to perform a narrative review of the available

evidence of possible relationships between chrono type, depression and physical

activities. The Electronic searches of the published literature were performed in the

databases National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health, in 2019, for the

last five years in the adult population. The results were grouped into three categories,

chrono type and depression in adults; depression and exercise/physical activity in

adults; chrono type and exercise/physical activity/sport in adults.

Evidence Synthesisː the importance of physical activities in combating depression is

quite evident in the literature, showing an inverse relationship between the level of

physical activity and depressive symptoms.

Conclusionsː However, many studies on depressive individuals do not identify the

chrono type as an important tool to integrate chronobiological aspects of human

behavior in the treatment of this disease. This review provides evidence for the scarcity

of studies on the relationship between chrono type, depression and physical activity.

Keywords

Sepression; Chronotypes; Physical activity; Exercise; Adults; Sport

Introduction

Circadian rhythmicity is present in a range of biological and

behavioral functions in all species and every cell; there is an

endogenous temporal mechanism capable of preparing the

organism in advance for external oscillations such as in the

light-dark cycle [1,2]. These endogenous diurnal variations

are determined by our internal circadian clocks and external

environmental cues called "zeitgebers". As examples of external

environmental cues are the light/dark cycle and social interactions

among others [3, 4].

The circadian timing system comprises the central clock in the

suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) located in the hypothalamus

and peripheral clocks in the body's peripheral tissues that are

controlled by the so-called clock genes [5, 4, 6]. These circadian

clocks are fixed, but undergo external stimulus adjustments

including sunlight, food, stress, exercise and temperature [7].

Circadian rhythms vary among people and are mainly influenced

by age, sex, hereditary and environmental influences [8, 3]. The variation of circadian rhythms among people may be classified

with the concept of circadian typology called chronotype

comprising three circadian types: the morning, the intermediate

and the evening type [9, 3].

The term chronotype was initially used by Horne and Östberg to

identify subjects with morning and evening preferences through

the questionnaire called HO Morning / Evening, which has 19

questions with scores ranging from 16 to 86 points, the lowest

scores are referring to people with afternoon characteristics and

the highest scores refer to people with morning characteristics,

where the afternoon will have a preference for the activities at

late hours and the morning with a preference for the activities at

early hours in the morning [10].

The importance for the investigation of chronotypes has grown

quickly and it is now accepted that circadian preference is

associated with physical and mental health, in terms of wellbeing,

but also some diseases [11, 12, and 1]. Some studies

have shown a relationship between evening chronotype and depressive symptoms [13, 14, 15, and 12].

A major depressive disorder is a mental illness responsible for

years of disability also is reflected as a list of risk factors with

mortality and morbidity worldwide [16]. The official diagnosis of

depression is subjective and rests on the documentation of a certain

number of symptoms that significantly impair functioning for certain

duration [17]. People with depression suffer from changes in body

composition [18], sleep [19-21], cortisol levels [22, 23], and body

temperature [24, 25]. It is important to explain the complex array

of symptoms related to the circadian activity. Recent studies

combining behavioral, molecular and electrophysiological

techniques reveal those certain aspects of depression result from

maladaptive stress in specific neural circuits.

Multiple research reports suggest that abnormalities in

circadian rhythms are involved in the etiopathogenesis of

mood disorders [26]. Due to the increasing number of cases of

people with depression, several studies seek alternatives for the

prevention and treatment of depression. For reference [26] the

pharmacological, psychological, and light treatments of mood

disorders have multiple effects on circadian function. Effects

of antidepressant drugs on the free-running circadian period

indicate that these medications affect the circadian pacemaker.

Antidepressants are considered the first line of treatment;

however, the response rate is considered low. Circadian rhythm

and altered physical activity have long been recognized as core

features of Major depression. Thus, physical activity has been

suggested as non-pharmacological treatments that should

complement traditional methods [27-31].

In this sense, it is important to expand a discussion on the

relationship between chronotype, depression, and physical

activity. Understanding whether there is a relationship between

the type of chronotype and depression, as well as whether physical

activity can minimize these effects, is extremely important for

the general health of the population suffering from depressive

symptoms. Therefore, this study aimed to review the available

evidence of possible relationships between chronotype, depression

and physical activity. The evening types show more depressive

symptoms than the morning ones. Thus, this study hypothesizes

that physical activity can positively modulate responses of

symptoms of depression in morning and afternoon patients.

Materials and Methods

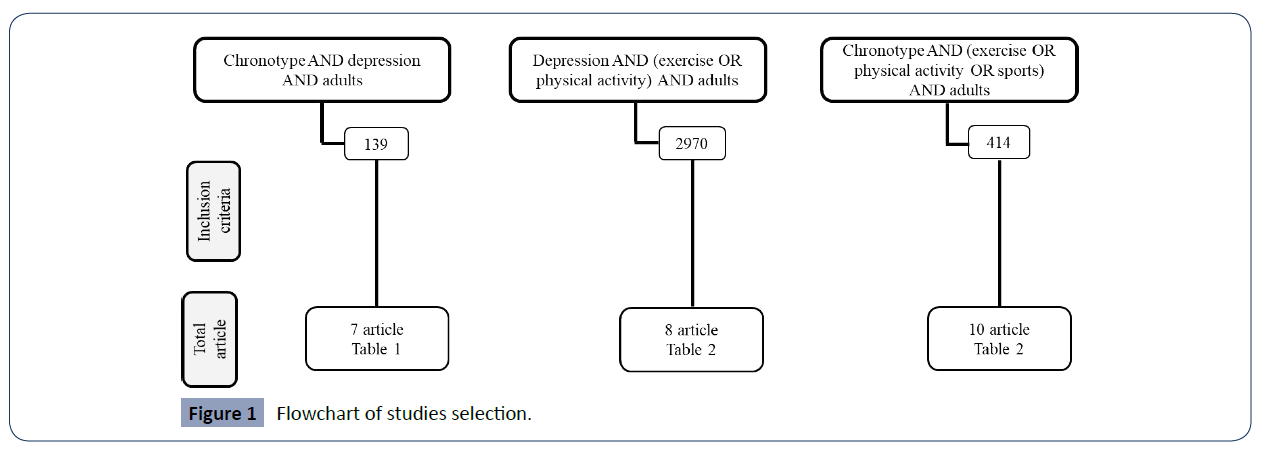

Four comprehensive surveys were performed at the National Library of Medicine (Pubmed) in 2019, with the first combination using the terms: "Depression AND Chronotype AND (exercise OR physical activity) AND adults". However, only 7 results were found and did not present the relationship between the three variables [Physical Activity, chronotype and depression]. In this sense, the searches were separated (Figure 1), initially with the following terms "Chronotype AND depression AND adults", being 139 articles identified. Inclusion criteria were: original articles; written in English; last 5 years; the relationship between depression and chronotype. Later the terms were used: "Depression AND (exercise OR physical activity) AND adults". In all, 2790 articles were found. Selection criteria were: written in English, original study; last 5 years; the relationship between exercise and physical activity with depression in adults. The last search used the following keywords: Chronotype AND (exercise OR physical activity OR sports) AND adults. In all 58 articles were found, the following criteria were applied: original article; written in English; present the relationship between chronotype and physical activity.

Analysis procedures

During the first screening, two reviewers (MJ or LT) evaluated the titles and abstracts of each citation and excluded irrelevant studies. For each potential study, two reviewers (FL or EL) examined the full article and assessed whether the studies fit within the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, a third evaluator would be contacted (NL).

Quality Assessment

The articles were evaluated based on internal validity (selection bias, performance bias, friction measurement bias and reports) and the validity construct (adequacy of the operational criteria used). In general, the quality of the evidence from the studies was assessed using three main measures: 1 limitation (poorly designed design, for example); 2- consistency of results; and 3- accuracy (ability to generalize findings and provide sufficient data). Studies that failed at these points were not added or selected (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Flowchart of studies selection.

Results

As a result of the first search, which identifies the relationship

between chronotype and depression in adults, 7 studies were

selected (Table I). The second search made it possible to

identify the relationship between exercise / physical activity and

depression in adults. At the end of the analyzes, 8 articles were

selected (Table II). In the third search, we found 10 studies that

evaluate the relationship of chronotype with exercise / physical

activity in adults (Table III). Since the instruments developed to

estimate chronotype are not equal the specific instrument used

has been indicated in the tables (Tables 1-3).

| Authors |

Objective |

Sample |

Depression Assessment |

Chronotype Assessment |

Relevant Results |

| (Reference 48) |

To report suicidality according to chronotype and seasonal pattern in patients with MDD. |

120 subjects (18 to 74years old). |

HAMD |

MEQ |

There was no significant difference in depression scores between morning and evening patients. However, patients with evening preference have a higher suicidal risk when compared to morning patients. |

| (Reference 47) |

To understand the associations between different dimensions of chronotype, depressive symptoms, and emotional eating. |

10000 subjects (25-74 years old). |

CES-D |

Original MEQ |

Preferences for morning hours were associated with lower scores of depressive symptoms. |

| (Reference 36) |

To study the relationship between chronotype and depression in a more representative sample size of the Finnish adult population. |

10503 subjects |

Self-report questionnaires, with four questions. |

MEQ |

The evening show more depressive symptoms than the morning ones, even after controlling for possible confounding factors (sex, age, education, living conditions, alcohol consumption, smoking and sleep). |

| (Reference 33) |

To examine the association between chronotypes and the presence of depressive and anxiety disorders in a large cohort, while taking into account relevant Sociodemographic, somatic health, and sleep factors. |

2596 participated in the second year. |

MDD and IDS |

MCTQ |

Individuals with evening chronotype are more likely to have depressive disorder, even when adjusted for health factors, Sociodemographic data, and sleep-related factors. |

| (Reference 32) |

To explore the role of cognitive reactivity and pathological worry in the association between eveningness and depression. |

1654 subjects, being 1227 depressions and 427 healthy controls. |

LEIDS-R |

MCTQ |

Results show that evening type scored higher on a specific psychological factor of vulnerability to depression. |

| (Reference 49) |

To examined whether differential relation of depression and seasonality to the morning and evening components of morningness-eveningness might be confirmed in analyses of a big dataset. |

2398 subjects |

CES-D |

A short (40-item) version SWPAQ |

Depression was found to be significantly linked to earliness-lateness, but only morning component of earliness-lateness demonstrates such a link. |

| |

|

Siberia. |

|

|

|

| (Reference 38) |

The purpose of this study was to investigate and analyze the role of depression in its effects on chronotype and sociality. |

2772 men |

PHQ-9 |

CSM |

Depressive symptoms and suicidal tendencies are significantly related to individuals with evening chronotype when compared to morning. |

| |

|

2860 women |

|

|

|

Table I. Summary of studies involving Chronotype and depression in adults

| Authors |

Objective |

Sample |

Depression Assessment |

Exercise Or |

Relevant Results |

| |

|

|

|

Physical Activity |

|

| (Reference 59) |

To Evaluate The Efficacy Of Four Months Of Aerobic Exercise Intervention In A Group Of Women Referred By Psychiatrists. |

26 Women Diagnosed With Clinical Depression. |

Bdi-Ii |

Intervention 8-Week, 3 Times-Weekly, One Hour Each Session. |

The Exercise Group When Compared To The Control Group Showed Improvement In Relation To Depression Parameters, And Higher Physical Fitness. |

| (Reference 60) |

To Examine The Efficacy Of A Self-Selected Intensity Aerobic Exercise Intervention In Outpatients With Depression, Assessing Depressive Symptoms As Well As Physical Fitness. |

46 Outpatients Diagnosed With |

Hrsd-17 |

Ukk2-Km Walk Test To Estimate Physical Fitness. Intervention 8-Week, 3 Times-Weekly, One-Hour Long Group Interventions On Monday, Wednesday And Friday Evenings. |

There Were Major Changes In The Depression Scores Assessed By The Hamilton Scale And Moderate Changes In The Bdi-Ii Assessment. |

| |

|

Mild To Severe Depression. |

And Bdi-Ii. |

|

|

| (Reference 58) |

Clarify Whether Depressive Symptoms Moderate The Relations Between Exercise And Same-Day Self-Efficacy, And Between Self-Efficacy And Next-Day Exercise. |

116 Subjects Physically Inactive, Being 75,9% Women. |

Ces-D |

Were Collected Every Day: (Today Did You Walk For At Least 10 Minutes At A Time At Your Normal Walking Pace, While At Work, For Recreation, To Get To And From Places, Or For Any Other Reason?) |

The Study Found That Self-Efficacy Was Higher On Days Exercise Occurred Compared With Days On Which It Did Not Occur. Second, We Found That Self-Efficacy On Day X Predicted Greater Odds Of Exercise On Day X+1. Thus, These Findings Self-Efficacy On One Day Predicts The Likelihood Of Exercising The Next Day, Regardless Of Depressive Symptoms. |

| (Reference 63) |

To Examine Independent And Combined Associations Of Pa And Sb With Depressive Symptoms Among Japanese Adults |

2914 Subjects. |

Using The Japanese Version Of Ces-D. |

Ipaq-Sv |

Physical Activity Is Related To Lower Risk Of Depressive Symptoms Independently. In Addition, Active People Have Fewer Depressive Symptoms Compared To High Sedentary Behavior. |

| (Reference 61) |

Prospectively Assess The Association Between Self-Reported Habitual Physical Activity Levels And Depression Severity Following A 12-Week Intervention |

629 Subjects, Being 75% Women. |

Phq-9 |

Adopted A Questionnaire And Score Conversion Method To Assess Habitual Physical Activity. The Questionnaire Was Developed By The Swedish School Of Sport And Health Science. |

Subjects With Higher Levels Of Physical Activity Responded Favorably To Treating Depression When Compared To Those Who Are Less Active. |

Table II. Summary of studies involving Exercise/Physical Activity and depression in adults

| Authors |

Objective |

Sample |

Chronotype Assessment |

Exercise Or |

Relevants Results |

| |

|

|

|

Physical Activity |

|

| (Reference 85) |

The Aim Of This Study Was To Measure The Response Of Morning Cyclists To A Standardized Bout Of Exercise Performed At Different Times Of The Day. |

20 Cyclists Who Were Categorized As Morning. |

Mepq |

All The Cyclists Had Participated In Recreational Cycle Races For The Past 2 Years And Trained At Least Twice Per Week. In Addition, These Cyclists Had Completed A Local, Annual 109 Km Cycle Race, Or A Similar Event, In Less Than 4 H Within The Past 2 Years |

Cyclists Classified As Morning, Submitted To The Same Physical Effort (Load And Intensity), At Different Times Of The Day, Demonstrate Higher Perception Of Effort, In Other Words, It’s More Difficult To Perform The Task At Night When Compared To The Execution In The Morning Period. |

| (Reference 86) |

The First Aim Was To Assess The Effect Of Marathon Start Time On Chronotype In Marathon Runners. The Second Aim Was To Determine The Extent To Which Either A High Level Of Physical Activity Or Climate Explains The Bias Towards Morningness Observed In South African Athletes And Controls. The Third Aim Was To Determine Whether Any Relationship Exists Between Chronotype, Per3vntr Polymorphism Genotype, Training Habits And Marathon Performance. |

381 Caucasian Male Marathon Runners (South African-Dutch) |

Meq |

Training History Data Included Actual And Preferred Training Time-Of-Day Information On Weeks Days And Weekends, As Well As Training Duration, Intensity And Distance (Run Groups); While Race History Data Included Personal Best Marathon And Half-Marathon Times. |

There Was Predominance In The Morning In Two Situations. When Comparing A Group Of South African Runners With Dutch Runners; Also When Comparing The Group Of Runners (South Africans And Dutch) With Their Respective Control Groups. |

| (Reference 88) |

To Extend The Current Evidence Base By Exploring How Sport Participation And Ptlid Relate To Chronotype Amplitude; To Explore How Chronotype Relates To Various Characteristics Of Sport Training And Competition; To Explore The Independent And Interrelated Contribution Of Sport Participation And Chronotype To Ptlid. |

Sample Included 976 Non-Athletes (493 Women And 483 Men) And 974 Athletes (478 Women And 496 Men). |

Caen Chronotype |

Participants Completed A Battery Of Questionnaires Targeting Sport Participation Characteristics, Six Positive Ptlid. |

Sport Participation Characteristics (Time Of Competition And Duration Of Training Sessions) Were Related To Chronotype Amplitude And Morningness–Eveningness. But Most Notable Was That Sport Participation Was Related To Amplitude But Not To Morningness-Eveningness. |

| |

|

|

Questionnaire |

|

|

| (Reference 87) |

To Compare 200 M Swimming Time-Trial (Tt) Performance, Rate Of Perceived Exertion And Mood State At 06h30 And 18h30 In Trained Swimmers |

26 (18 Men And 8 Women) Trained Caucasian Swimmers (25-50 Years Old) |

Meq |

The Swimmers Performed A 200 M Freestyle Tt At Either 06:30 A.M And 6:30 P.M. Each Session Was Separated By A Minimum Of 3 Days To Allow For Recovery. |

The Results Show That Swimmers Who Trained In The Morning Were Faster In The Time Trial In The Morning, While Those Who Trained At Night Were Faster In The Test At Night. However, There Was No Difference Between Morning And Evening Performance When The Swimmers Were Considered As A Single Group. |

Table III. Summary of studies involving Chronotype and Exercise/Physical Activity in adults

The relationship between depression and

Chronotype in adults

The evening is among people that exhibited more symptoms of depression than the morning and intermediate types [15, 32- 40], but the underlying mechanism is still unclear. A possible

reason could be the transformation of our modern society into

a technological society that does not take into account the

importance of chronotype on human health. Nowadays, many

people spend an increasing amount of time in front of computer

screens mainly during night time and these habit changes can

force people to become more evening. Exposure to blue light

from computer and cell phone screens can lead to disturbances

in melatonin secretion and alterations in circadian physiology,

alertness, and cognitive performance levels.

Among patients undergoing cognitive-behavioral therapy [41]

those characterized as evening types have significantly more

depressive symptoms, insomnia and irregular sleep-in relation

to the intermediate and morning patients. A meta-analysis [42] identified that both short and long sleep duration is related to

the increase in depressive symptoms in people characterized

as evening types [42]. Short duration, mainly due to increased

daytime tiredness [43], while, and long sleep duration due to

decreased physical activity [44].

Regarding well-being satisfaction, evening types have less

satisfaction with life and are subject to developing psychiatric

problems [45]. Dissatisfaction occurs mainly because evening

people need to adapt to morning routines which causes an

imbalance between personal and external rhythms. The time of taking antidepressants can also clarify this relationship since

medications taken at night can cause an excitatory effect and

delaying sleep onset. As a consequence, people wake up earlier

than they would like favoring changes to the internal clock46.

Besides [33] investigated those subjects characterized as evening

tend to report variation in daytime mood, with the morning time

being the period of greatest instability, these changes leave the

subjects exposed to negative feelings that favor depression.

Our search demonstrates a lack of consensus in the literature

on the type of chronotype and the increase in symptoms of depression. Some studies found an association between higher

depression scores to the evening chronotype. A large cohort study

using the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire found an association

of depressive and/or anxiety disorders with late chronotype

after adjusting for Sociodemographic, somatic health, and sleeprelated

factors [33]. Also, the same research group demonstrated

that depress genic cognitions are more prevalent in the evening

suggesting a possible link between chronotype and depression

[32]. Another research carried out in Finland, showed that the

night chronotype is related to depression, in a sample with an

age range of [25-74] years old, and the association remains after

controlling for sex, age, education, living conditions, consuming

alcohol, smoking and sleep36. A Finnish population-based

study showed that morning preference and high alertness in

the morning were associated with lower scores of depressive

symptoms and emotional eating47. The first two studies used the

Munich Chronotype Questionnaire that measures the phase of

sleep positions for both free and working days whereas the later

used Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire that evaluates

the phase preferences of individual behavior over a 24h day.

Reference48 also studied patients diagnosed with major

depressive disorder. There was a relationship between suicide

risk in the evening chronotype and hypomanic personality traits.

The risk of suicide was also observed in university students with

symptoms of depression at night. Suicide risk was also observed

in university students with symptoms of depression and evening

chronotype [38]. Depression was also found to be significantly

associated with earliness-lateness, but only the morning

component of earliness-lateness demonstrates such association

[49].

Physical activity and depression in adults

The benefits of physical exercise / physical activity programs

are pointed out as important tools in the treatment of

depression. Although the mechanisms are still quite confusing,

some hypotheses move towards the anti-inflammatory effect

that physical exercise promotes [50], such as lower levels of

interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein [51].

Others point to the fact that depressed individuals have a

decrease in hippocampus neurogenesis, in this sense [52], points

out the antidepressant effect of exercise on the capacity that it

has to increase the hippocampus neurogenesis, which occurs

due to a possible increase in endorphins –b [53] also, by the

increase in the brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF), which

are responsible for neural development and survival [54].

There are also physiological mechanisms that justify the

relationship between physical activity and changes in the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) in depressed

individuals [55], in hormonal changes in serotonin [56] and

noradrenaline levels [57]. However, physical exercise is capable of

promoting changes in the function of HPA55, capable of causing

changes in the levels of serotonin [56], and noradrenaline [57].

The literature points out those depressive individuals tend not to

be involved in physical activity programs; therefore, psychological

factors influence the responses of the activity/exercise effect

on the treatment of depression. Reference [58] observed that

self-efficacy, that is, the individual's ability to perform a certain

behavior, is related to the start of a physical exercise program

by people with high symptoms of depression self-efficacy during

interventions in people with depression.

There is confusion between the role of habitual physical activity

and physical exercise as a dose-response for the treatment of

depression. Reference [59] demonstrated that 16 weeks of

aerobic exercise of light to moderate intensity is sufficient to

decrease the symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress, and

positive changes in the physical fitness of depressed patients

compared to the control group. Also, aerobic physical exercise

causes an antidepressant effect regardless of intensity, a fact

observed by reference [60] in which the subject chose the

intensity of the exercise session and at the end of 8 weeks

there was a significant improvement in symptoms. In this sense,

coaches must know the importance of performing the exercise

in psychological aspects and not worry only about physiological

changes.

Despite the studies that seek to explain the relationship between

the level of physical activity and depressive symptoms present a

significant number of subjects; a major limitation of these studies

is that they assess physical activity through questionnaires [61- 65]. The results demonstrate a reduction in depressive symptoms

with increased levels of physical activity.

Other studies have already investigated the relationship between

physical activity and depression using different measurement

variables. Physical activity was included in the routine of patient

visits for 14 weeks and an increase in the number of steps/day

monitored by a pedometer was observed, the study suggests

that physical activity be included in the treatment of depression

[27].

Reference [66] compared three forms of treatment for

depression [antidepressant/exercise / behavioral therapy after

12 weeks, all of which had significant improvement in symptoms.

Also, in the elderly, it was identified that antidepressant

medication is effective for a response fast, but after 16 weeks of

aerobic exercise [70-85% HR reserve], per- forming three weekly

sessions, the effects on depression levels are comparable to the

use of medication and the use of medication plus exercise [67].

Physical activity was also associated with improvements in

depression scores in a study that monitored women for 32

years (1974-2005). Depression scores and physical activity were

measured in the years 1974, 1992, 2000 and 2005. The authors

conclude that the higher the depression scores the lower the level

of physical activity and over the years the decrease in physical

activity also pointed to an increase in depression scores [68].

In addition to regular physical activity, sedentary behavior, that

is, the daily time spent performing sedentary activities is also

related to depression. Reference [69] compared the average time

that men and women with an average age of 64 years, spend

watching TV, and noticed that people who spend six or more

hours a day watching TV have higher depression scores when

compared to people who stay less than 2 hours a day. In children

and adolescents, the longer the screen time, that is, sedentary

behavior, the greater the risk of developing depression, with the lowest risk being observed in less than one hour/day and the

risks are significantly increased above two hours/day [70].

Evaluated in adults the time spent in physical activities and the

time in sedentary activities, using an accelerometer, the study

concluded that the increase in depressive symptoms is related to

the decrease in light physical activity and increase in sedentary

behavior [71].

There is also evidence that the total weekly energy expenditure

(EE) is related to depression scores. Men and women were divided

into a group with a GE of 7kcal / kg/week and an EE group of

17.5kcal / kg/week (public health dose), both groups subdivided

into 3 and 5 times a week of aerobic exercise on a bicycle in

the laboratory, beyond the control group (flexibility exercises

3 times a week). Groups with EE within the recommended for

health, after 12 weeks of training, showed a significant reduction

in depression scores, while the other two groups showed values

similar to the control group [72].

Another study with 9580 men was evaluated for depressive

scores and level of physical activity, with the following groups:

inactive (0 MET • min • week−1), low (1-499 MET • min • week−1),

medium (500-999 MET • min • week−1) and high (≥1000 MET

• min • week−1). When comparing the inactive group with the

low, medium and high groups, the probability of developing

depression is 24%, 51% and 51%, respectively [73].

Several review articles and Meta analyzes were also published

to clarify the relationship between physical exercise and physical

activity with depression [61,74-77]. However, it is not still

unclear, the ideal dose of physical activity / physical exercise

that should be "ad- ministered" daily or at intervals of days for

the treatment of depression, nor if the reduction of the time

allocated to sedentary activities would be enough to prevent or

treat depression.

Physical activity and Chronotype in adults

The estimates that 1 in 4 adults don’t meet the global needs for

physical activity. That is, even with all the global campaigns and

recommendations for regular physical activity, as a strategy for

the prevention and treatment of diseases as people who don't

perform or are necessary. Besides, as changes in countries'

economic patterns, the sedentary lifestyle, (greater access to

transport, technology and urbanization) [78].

Strategies must be implemented to break the barriers (lack of

motivation, time, energy and adequate equipment) that prevent

people from starting and staying in physical activity programs

[79]. In this sense, identifying the chronotype profile of sedentary

individuals can contribute to these individuals starting an exercise

program. That is, the time to perform physical activity should

be linked to that individual's preference period, increasing the

probability of activities happening [80].

Our findings show that the studies that evaluated the relationship

between chronotype and physical activity are mostly transversal,

and present many methodological differences, such as the profile

of the subjects, exercise models, instruments to characterize

chronotype and physical activity, factors that make it difficult to

compare studies.

Subjects characterized as morning people have an independent

relationship with the frequency of self-reported exercise [80].

Morning people also show less perceived effort during a walking

activity performed in the morning when compared to nighttime

exercise in the morning [81]. Furthermore, morning people

have significantly more physical activity than evening and

intermediate [82]. Also, the evening profile shows a reduced

amount of physical activity and greater involvement in sedentary

activities, monitored by accelerometer [83]. These findings were

also observed84, in which the evening showed a lower amount of

physical activity and more time sitting in minutes/day, assessed

by questionnaire when compared to the morning ones.

Reference [84], also observed that when separating the

investigated sample and evaluating only the working subjects, all

chronotypes show less physical activity when compared to the

morning. The authors point out those evening subjects difficult

to do physical activities in the morning or afternoon periods. And

the evening periods they are usually in work activities or studies,

while in the morning people find it easier to do activities, so they

tend to be more active.

In groups of athletes such as cyclists with a morning chronotype,

they had a greater perception of effort in performing activities

in the afternoon/night when compared to exercises in the

same load and intensity performed in the morning85. Already,

when comparing the type of chronotype, of a group of South

African runners and with Dutch runners, there was morning

predominance in South Africans, also the greater number of

morning runners when comparing runners (South Africans

and Dutch) with sedentary control groups (South African and

Dutch). In addition, the best personal brands in half marathons

and marathons for South African runners were achievements

in morning tests86. Usually, runners wake up early to train and

this is associated with preferences for realizing activities. In

swimmers, the morning chronotype was associated with lower

fatigue scores, better time against the clock, and lower perceived

effort scores [87].

Another relevant point is the results found in88, in which, in

addition to determining the type of chrono- type of the evaluated

subjects, they characterize the amplitude of each individual's

chronotype. Amplitude is characterized as a component

of circadian rhythm and is related to the ability to tolerate

an unpleasant situation [8]. In the study by reference [88],

Involvement in sports activities was related to the chronotype

amplitude, but not to the type.

A specific group of people (Live in the Arctic Circle) [89] observed

that after a physical exercise program, VO2max had a smaller

increase in morning subjects when compared to the evening.

However, the larger increase in their strength indexes is better

in the type morning when compared to the type evening. It is

important to highlight that few studies address this theme and

the influence of the environment with little external light and the

behavior of each chronotype.

Physical activity, Chronotype and depression in

adults

The relationship between physical activity, chronotype and depression has not been extensively studied in the adult

population. In this review, we identified that most studies that

relate to two of the three variables studied are cross-sectional;

the assessment of physical activity is done in a subjective way, as

well as depression, which is based on the use of a questionnaire

and not a clinically diagnosed sample. However, some studies

that did not present the keywords used in our research seek to

clarify some possible explanations for this relationship.

A randomized control trial study with evening types used practical

interventions including light exposure, fixed meal times, caffeine

intake, and exercise to shift the late timing of evening types to an

earlier time. The phase advance of 2 h in evening types improved

self-reported depression and stress, isometric grip strength

performance, and reaction time suggesting a simple strategy to

improve mental wellbeing and performance [90]. As recently

observed by [91], autography data showed reduced physical

activity levels and daily rhythm disturbances among people with

depressive and anxiety disorders. Using a less frequent measure

of chronotype, the sleep midpoint on free days, the authors did

show an association between evening chronotype with physical

activity and depression. The strength of this work was the

assessment of sleep and physical activity by actigraphy [91].

In a study of preclinical medical students, evening chronotype

was associated with less happiness in comparison to the morningtype

and intermediate-type individuals. Also, depression and

physical activity were among the factors that predict happiness

among Turkish preclinical medical students [92]. Another survey,

also with medical students from China, found that nocturnal

types perform little physical activity, a lot of sedentary behavior

and make a greater intake of drinks with caffeine [93].

Recently [94], investigated the social jetlag of workers and

related it to different variables [physical activity, depression,

lifestyle, work routine]. It was observed that the largest social

jetlag was related to people with a type evening chronotype,

with the highest scores of depression scores, and poor sleep

quality characteristics observed in women, young people, blue

collar workers and those who use smoking, but they were also

physically active both at work and at leisure.

Precise mechanisms linking chronotype, depression and physical

activity are unclear. The relationship between depression and

chronotype can be explained by the relationship between the

sleep-wake circadian cycle and the secretion of neurotransmitters,

such as serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine [95]. We know

that in the modern lifestyle, this relationship is influenced by the

pace of life of people, high level of physical and psychological

stress, due to extensive work hours and sleep deprivation. As

well as the relationship between physical activity and depression,

as physical activity increases the levels of serotonin, dopamine

and norepinephrine in the hippocampus region, which increases

the feeling of well-being However, in relation to chronotype and physical activity, it seems that the main characteristics are in the

fact that morning type individuals tend to be more active, the

relationship can be clarified by the fact that these subjects do not

have problems waking up early, and that is why they are able to

better adapt the routine, work/study with time for exercise. The

types evening is unable to wake up early and generally the night

have no time available because they are involved in work and/

or study.

However, with the increase in the number of people diagnosed

with depression, with the current situation experienced in the

world, longitudinal investigations are urgently needed to monitor

people clinically diagnosed with depression, submitted to

physical exercise programs, appropriate to preference schedules,

to clarify the relationship between these variables, as well as to

better prescribe physical exercise to prevent and minimize the

effects caused by depression.

Conclusion

The influence of chronotype on performance and on the general

health of individuals and on the relationship with metabolic

diseases has been investigated. However, further studies

are needed to establish the specific relationship between

chronotype, physical activity and depression. In our review, we

found that many studies indicate that higher depression scores

and lower levels of physical activity are found mainly in evening or

intermediate types. What makes it difficult to compare is the fact

that researches do not distinguish whether this relationship can

be influenced by the depression classification of the investigated

subjects, or by the characteristics of the physical exercise

[intensity, volume and physical exercise] performed. Other

factors that were not considered in the studies are sleeping,

eating, working and the time of physical activity.

Understand the pattern of preferences [morning or evening]

of the subjects and the current routine of life [hours at work

/ study] can be important mechanisms to start a physical

activity program, promoting improvement in general health.

Furthermore, the importance of physical activity in combating

depression is quite evident and suggested by the literature.

However, the explanations of the possible physiological and

psychological mechanisms that influence this relationship are

still under investigation.

Simple strategies to improve mental wellbeing by targeting

circadian disruption without the need for pharmacological

agents can be used in the treatment of depression. Identifying

the chronotype in individuals with depression can be the first

step to start a chronobiological intervention including the time of

physical activity, meal time, sleep/awake cycles that will improve

mental wellbeing. Despite the need for further research, this

remains an exciting prospect for a large number of people that

suffer from reduced mental well-being.

REFERENCES

- Mukherji A, Bailey SM, Staels B, Baumert TF (2019) The circadian clock and liver function in health and disease. J Hepatol 71:200-211.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Roenneberg T, Merrow M (2016) The circadian clock and human health. Curr Biol 26:R432-R443.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Roenneberg T Daan S, Merrow M (2003) The art of entrainment. J Biol Rhythms 18:183-194.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Vieira E, Burris TP, Quesada I (2014) Clock genes, pancreatic function, and diabetes. Trends Mol. Med 20:685-693.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS (2012) Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci 35:445-462.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Vieira E, Ruano EG, Figueroa ALC, Aranda G, Momblan D et al. (2014) Altered clock gene expression in obese visceral adipose tissue is associated with metabolic syndrome. PloS one 9:e111678.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Tahara Y, Aoyama S, Shibata S (2017) The mammalian circadian clock and its entrainment by stress and exercise. J Physiol Sci 67:1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Adan A, Archer SN, Hidalgo MP, Di Milia L, Natale V et al. (2012) Circadian typology: a comprehensive review. Chronobiology international. 29:1153-1175.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Granada AE, Bordyugov G, Kramer A, Herzel H (2013) Human chronotypes from a theoretical perspective. PLoS One 8:e59464.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Horne JA, Östberg O (1976) A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Chronobiol Int

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Basnet S, Merikanto I, Lahti T, Männistö S, Laatikainen T (2017) Associations of common noncommunicable medical conditions and chronic diseases with chronotype in a population-based health examination study. Chronobiology International. 34:462-470.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Kivelä L, Papadopoulos MR, Antypa N (2018) Chronotype and psychiatric disorders. Curr Sleep Med Rep 4:94-103.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Au J, Reece J (2017) The relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 218:93-104.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Fares S, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, White D, Hickie IB et al. (2015) Clinical correlates of chronotypes in young persons with mental disorders. Chronobiology international 32:1183-1191.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Hidalgo MP, Caumo W, Posser M, Coccaro SB, Camozzato AL, Chaves MLF (2009) Relationship between depressive mood and chronotype in healthy subjects. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 63:283-290.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Hallgren M, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Lundin A, Jaakallio P et al. (2017) Treatment guidelines for depression: greater emphasis on physical activity is needed. Eur Psychiatry 40:1-3.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Krishnan V, Nestler E (2008) The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 455: 894–902.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Becofsky KM, Sui X, Lee D-c, Wilcox S, Zhang J et al. (2015) A prospective study of fitness, fatness, and depressive symptoms. Am J Epidemiol 181:311-320.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Franzen PL, Buysse DJ (2008) Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 10:473.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Murphy MJ, Peterson MJ (2015) Sleep disturbances in depression. Sleep Med Clin 10:17

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Nutt D, Wilson S, Paterson L (2008) Sleep disorders as core symptoms of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 10:329.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Dedovic K, Ngiam J (2015)The cortisol awakening response and major depression: examining the evidence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11:1181–1189.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Qin D-d, Rizak J, Feng X-l, Yang S-c, Lü L-b, et al. (2016) Prolonged secretion of cortisol as a possible mechanism underlying stress and depressive behaviour. Sci Rep 6:30187.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Hanusch K-U, Janssen CH, Billheimer D, Jenkins I, Spurgeon E, et al. (2013) Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depression: associations with thermoregulatory cooling. Am J Psychiatry 170:802-804.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Janssen CW, Lowry CA, Mehl MR, Allen JJ, Kelly KL, et al. (2016) Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 73:789-795.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Sher L (2003) Etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of seasonal and non-seasonal mood disorders: possible role of circadian rhythm abnormalities related to developmental alcohol exposure. Med Hypotheses 62:797–801.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Adams DJ, Remick RA, Davis JC, Vazirian S, Khan KM (2015) Exercise as medicine—the use of group medical visits to promote physical activity and treat chronic moderate depression: a preliminary 14-week pre–post study. BMJ Open SEM 1:e000036.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Choi KW, Zheutlin AB, Karlson RA, Wang MJ, Dunn EC, et al. (2020)Physical activity offsets genetic risk for incident depression assessed a electronic health records in a biobank cohort study. Depress Anxiety 37:106-114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Park JE, Lee JY, Kim BS, Kim KW, Chae SH, et al. (2015) Above‐moderate physical activity reduces both incident and persistent late‐life depression in rural Koreans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 30:766-775.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, et al. (2018)Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry 175:631-648.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Sui X, Rosenbaum S, Firth J, et al. (2016) Are lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness associated with incident depression? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Prev Med 93:159-165.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Antypa N, Verkuil B, Molendijk M, Schoevers R, Penninx BW, et al. (2017) Associations between chronotypes and psychological vulnerability factors of depression. Chronobiol Int 34:1125-1135.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Antypa N, Vogelzangs N, Meesters Y, Schoevers R, Penninx BW (2016) Chronotype associations with depression and anxiety disorders in a large cohort study. Depress Anxiety 33:75-83.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Kitamura S, Hida A, Watanabe M, Enomoto M, Aritake-Okada S, et al. (2010)Evening preference is related to the incidence of depressive states independent of sleep-wake conditions. Chronobiol Int 27:1797-1812.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Levandovski R, Dantas G, Fernandes LC, Caumo W, Torres I, et al. (2011) Depression scores associate with chronotype and social jetlag in a rural population. Chronobiol Int 28:771-778.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Merikanto I, Kronholm E, Peltonen M, Laatikainen T, Vartiainen E, et al (2015) Circadian preference links to depression in general adult population. J Affect Disord 188:143-148.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Merikanto I, Lahti T, Kronholm E, Peltonen M, Laatikainen T, et al. (2013) Evening types are prone to depression. Chronobiol Int 30:719-725.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Park H, Lee H-K, Lee K (2018) Chronotype and suicide: the mediating effect of depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Res 269:316-320.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Prat G, Adan A (2013) Relationships among circadian typology, psychological symptoms, and sensation seeking. Chronobiol Int 30:942-949.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Roaldset JO, Linaker OM, Bjorkly S (2012) Predictive validity of the MINI suicidal scale for self-harm in acute psychiatry: a prospective study of the first year after discharge. Arch Suicide Res 16:287-302.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Ong JC, Huang JS, Kuo TF, Manber R (2007) Characteristics of insomniacs with self-reported morning and evening chronotypes. J Clin Sleep Med 3:289-294.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Zhai L, Zhang Y, Zhang D (2015) Sedentary behaviour and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 49:705-709.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Shen J, Barbera J, Shapiro CM (2006) Distinguishing sleepiness and fatigue: focus on definition and measurement. Sleep Med Rev 10:63-76.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Stranges S, Dorn JM, Shipley MJ, Kandala N-B, Trevisan M et al. (2008) Correlates of short and long sleep duration: a cross-cultural comparison between the United Kingdom and the United States: the Whitehall II Study and the Western New York Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 168:1353-1364.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Diaz-Morales JF, Jankowski KS, Vollmer C, Randler C (2013) Morningness and life satisfaction: further evidence from Spain. Inter Chronobiol 30:1283-1285.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Knapen SE, Riemersma-Van der Lek RF, Antypa N, Meesters Y, Penninx BW et al. (2018) Social jetlag and depression status: results obtained from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety. Inter Chronobiol 35:1-7.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Konttinen H, Kronholm E, Partonen T, Kanerva N, Mannisto S et al. (2014) Morningness-eveningness, depressive symptoms, and emotional eating: a population-based study. Inter Chronobiol. 31:554-563.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Bahk Y-C, Han E, Lee S-H (2014) Biological rhythm differences and suicidal ideation in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 168:294-297.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Putilov AA (2018) Associations of depression and seasonality with morning-evening preference: comparison of contributions of its morning and evening components. Psychi res 262:609-617.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS et al. (2011) The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11:607-615.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Kohut M, McCann D, Russell D, Konopka D, Cunnick J (2006) Aerobic exercise, but not flexibility/resistance exercise, reduces serum IL-18, CRP, and IL-6 independent of β-blockers, BMI, and psychosocial factors in older adults. Brain, behavior, and immunity 20:201-209.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Ernst C, Olson AK, Pinel JP, Lam RW, Christie BR (2006) Antidepressant effects of exercise: evidence for an adult-neurogenesis hypothesis? J Psychiatry Neurosci.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Persson AI, Thorlin T, Bull C, Zarnegar P, Ekman R (2003) Mu‐and delta‐opioid receptor antagonists decrease proliferation and increase neurogenesis in cultures of rat adult hippocampal progenitors. Eur J Neurosci 17:1159-1172.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Cotman CW, Berchtold NC (2002) Exercise a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends neurosci 25:295-301.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Wittert G, Livesey J, Espiner E, Donald R (1996) Adaptation of the hypothalamopituitary adrenal axis to chronic exercise stress in humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28:1015-1019.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Jacobs BL (1994) Serotonin motor activity and depression-related disorders. Am Scient 82:456-463.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Dishman RK (1997) Brain monoamines, exercise, and behavioral stress: animal models. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Kangas JL, Baldwin AS, Rosenfield D, Smits JA, Rethorst CD (2015) Examining the moderating effect of depressive symptoms on the relation between exercise and self-efficacy during the initiation of regular exercise. Health Psych 34:556.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Carneiro LS, Fonseca AM, Vieira-Coelho MA, Mota MP, Vasconcelos-Raposo J (2015) Effects of structured exercise and pharmacotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy for adults with depressive symptoms.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Doose M, Ziegenbein M, Hoos O, Reim D, Stengert W et al. (2015) Self-selected intensity exercise in the treatment of major depression: a pragmatic RCT. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 19:266-275.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Hallgren M, Herring MP, Owen N, Dunstan D, Ekblom O et al. (2016) Exercise, physical activity, and sedentary behavior in the treatment of depression: broadening the scientific perspectives and clinical opportunities. Frontie psychia 7:36.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Kim S-Y, Jeon S-W, Shin D-W, Oh K-S, Shin Y-C (2018) Association between physical activity and depressive symptoms in general adult populations: an analysis of the dose-response relationship. Psychiatry Res 269:258-263.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Liao Y, Shibata A, Ishii K, Oka K (2016) Independent and combined associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with depressive symptoms among Japanese adults. IJBM 23:402-409.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Porras-Segovia A, Rivera M, Molina E, Lopez-Chaves D, Gutiérrez B et al. (2019) Physical exercise and body mass index as correlates of major depressive disorder in community-dwelling adults: Results from the PISMA-ep study. J Affect Disord 251:263-269.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Wassink-Vossen S, Collard R, Hiles S, Voshaar RO, Naarding P (2018) The reciprocal relationship between physical activity and depression: Does age matter? European Psychiatry 51:9-15.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Hallgren M, Kraepelien M, Lindefors N, Zeebari Z, Kaldo V et al. (2015) Physical exercise and internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy in the treatment of depression: randomised controlled trial. B J Psych 207:227-234.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, Craighead WE, Herman S et al. (1999) Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med 159:2349-2356.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Gudmundsson P, Lindwall M, Gustafson DR, Ostling S, Hällström T (2015) Longitudinal associations between physical activity and depression scores in Swedish women followed 32 years. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 132:451-458.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Hamer M, Stamatakis E (2014) Prospective study of sedentary behavior, risk of depression, and cognitive impairment. Med Sci Sports Exerc 46:718.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Liu M, Wu L, Yao S (2016) Dose response association of screen time-based sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents and depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Sports Med 50:1252-1258.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Helgadottir B, Forsell Y, Ekblom O (2015) Physical activity patterns of people affected by depressive and anxiety disorders as measured by accelerometers: a cross-sectional study. PloS one. 10:e0115894.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, Clark CG, Chambliss HO (2005) Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med 28:1-8.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Sieverdes JC, Ray BM, Sui X, Lee D-C, Hand GA, Baruth M, Blair SN (2012) Association between leisure time physical activity and depressive symptoms in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44:260-265.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Blake H (2012) Physical activity and exercise in the treatment of depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 3:106.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Deslandes A, Moraes H, Ferreira C, Veiga H, Silveira H et al. (2009) Exercise and mental health: many reasons to move. Neuropsycho 59:191-198.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Mathersul DC, Rosenbaum S (2016) The roles of exercise and yoga in ameliorating depression as a risk factor for cognitive decline. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Schuch FB, Morres ID, Ekkekakis P, Rosenbaum S, Stubbs B (2017) A critical review of exercise as a treatment for clinically depressed adults: time to get pragmatic. Acta neuropsychiatrica 29:65-71.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Organization WH (2018) Global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030: more active people for a healthier world: at-a-glance World Health Organization.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W (2002) Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:1996-2001.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Hisler GC, Phillips AL, Krizan Z (2017) Individual differences in diurnal preference and time-of-exercise interact to predict exercise frequency. Ann Behav Med 51:391-401.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Rossi A, Formenti D, Vitale JA, Calogiuri G, Weydahl A (2015) The effect of chronotype on psychophysiological responses during aerobic self-paced exercises. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 121:840-855.

Google Scholar

- Suh S, Yang H-C, Kim N, Yu JH, Choi S (2017) Chronotype differences in health behaviors and health-related quality of life: a population-based study among aged and older adults. Behav Sleep Med 15:361-376.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Gubelmann C, Heinzer R, Haba-Rubio J, Vollenweider P, Marques-Vidal P (2018) Physical activity is associated with higher sleep efficiency in the general population. the CoLaus study Sleep 41:zsy070.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Wennman H, Kronholm E, Partonen T, Peltonen M, Vasankari T, Borodulin K (2015) Evening typology and morning tiredness associates with low leisure time physical activity and high sitting. Chronobi inter 32:1090-1100.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Kunorozva L, Roden LC, Rae DE (2014) Perception of effort in morning-type cyclists is lower when exercising in the morning. J Sports Sci 32:917-925.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Henst RH, Jaspers RT, Roden LC, Rae DE (2015) A chronotype comparison of South African and Dutch marathon runners: The role of scheduled race start times and effects on performance. Chronob intern 32:858-868.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Rae DE, Stephenson KJ, Roden LC (2015) Factors to consider when assessing diurnal variation in sports performance: the influence of chronotype and habitual training time-of-day. Eur J Appl Physiol 115:1339-1349.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Laborde S, Guillen F, Dosseville F, Allen MS (2015) Chronotype, sport participation, and positive personality-trait-like individual differences. Chronobiol inter 32:942-951.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Vitale JA, Weydahl A (2017) Chronotype, physical activity, and sport performance: a systematic review. Sports Medicine 47:1859-1868.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Facer-Childs ER, Middleton B, Skene DJ, Bagshaw AP (2019) Resetting the late timing of ‘night owls’ has a positive impact on mental health and performance. Sleep medicine 60:236-247.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Difrancesco S, Lamers F, Riese H, Merikangas KR, Beekman AT et al. (2019) Sleep circadian rhythm, and physical activity patterns in depressive and anxiety disorders: A 2‐week ambulatory assessment study. Depre anxi 36:975-986.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Tan MN, Mevsim V, Pozlu Cifci M, Sayan H, Ercan AE (2020) Who is happier among preclinical medical students: the impact of chronotype preference. Chronobiol Intern 1-10.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Dong J, Guo T, Tang X et al. (2018) Caffeinated drinks intake, late chronotype, and increased body mass index among medical students in Chongqing, China: a multiple mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:1721.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Islam Z, Hu H, Akter S, Kuwahara K, Kochi T et al. (2020) Social jetlag is associated with an increased likelihood of having depressive symptoms among the Japanese working population: the Furukawa Nutrition and Health Study. Sleep 43:zsz204.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Salgado-Delgado R, Tapia Osorio A, Saderi N, Escobar C (2011) Disruption of circadian rhythms: a crucial factor in the etiology of depression. Depres res treat.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- He S-B, Tang W-G, Tang W-J, Kao X-L, Zhang C-G et al. (2012) Exercise intervention may prevent depression. Int J Sports Med 33:525-530.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Tonello L, De Andrade MJO,

Vieira E (2022) Chronotype Depression

And Physical Activity: A Relationship To Be

Studied? Health Sci J. Vol. 16 No. 5: 944.