Keywords

Familial, estradiol, prolactin, estrogen receptor.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer death worldwide. Despite the numerous uncertainties surrounding the etiology of breast cancer, intensive genetic, epidemiological and clinical studies identified many risk factors associated with breast cancer [1]. Breast cancer risk factors include age, family history of breast cancer (5-10% of breast cancers are associated with defined gene mutation like BRCA mutations), early menarche and late parity and high circulating levels of steroid hormones [2-4]. Recently, chemo preventive trials showed that women who use anti-estrogen agents in the breast have reduced risk for breast cancer compared with those who do not use the drug [5]. Determining the association between circulating hormones and breast cancer risk may provide an insight into the etiology of this disease and may help identify women who are at high risk. This study aimed to determine circulating plasma hormones, estrogen and progesterone receptor status and correlate them with breast cancer risk among familial and non-familial females.

Estrogens are synthesized from androgens in premenopausal ovary and in extra ovarian tissue including fat, muscle, liver and the breast by the conversion of cholesterol which is made by the adrenal gland in post menopausal females. Estrogen contribute to tumor by promoting the proliferation of cells with existing mutation or perhaps by increasing the opportunity for mutations that regulate the growth and differentiation of mammary cells which may play an important role in the development of breast cancer [4-6]. Few studies demonstrate the association between breast cancer and circulating levels of estrogen has now been well confirmed among postmenopausal women [7-8]. In contrast a relatively few studies on circulating hormone levels and breast cancer have been conducted in premenopausal women. This is largely due to variation in sex steroid hormone levels, particularly estrogen over the menstrual cycle. Thus further assessments are needed to evaluate the association between estrogen level and breast cancer risk among females.

Prolactin is a paradoxical hormone known as the pituitary hormone of lactation, which has more than 300 actions correlated to quasi-ubiquitous distribution of its receptors, lactation and reproduction [9]. It may increase breast cancer proliferation and inhibit apoptosis [10]. Prolactin levels and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women has been studied, and a significant positive association has been observed among both pre and postmenopausal breast cancer females [11-12].

Progesterone has been hypothesized to both decrease and increase breast cancer risk [13-14]. Progesterone levels appear to be a modest risk factor for both pre and postmenopausal breast cancer with significant inverse association among progesterone levels and breast tumors risk [15-16].

Women with family history of breast cancer are at increased risk of this disease, but no study shows the relation between plasma hormones levels and familial breast cancer. Multiple lines of evidence support the role of hormones in the etiology of breast cancer [4]. The aim of this study is to determine the level and evaluate the role of estradiol, progesterone and prolactin as risk factors among familial and non familial breast cancer. At the same time, correlate these levels with estrogen and progesterone receptor status.

Material and Method

140 benign and malignant breast cancer females attending King Hussein Medical Center and Al-Basheer hospital(Amman, Jordan) during the period between June 2007 and May 2011 were enrolled in this study. Participants had signed a consent form and were interviewed to complete a questionnaire form including information about age, family history of breast cancer and therapy and medication. Malignant breast cancer and benign patients were categorized into familial breast cancer according to breast cancer history (family have at least one first degree or second-degree relatives diagnosed with breast cancer).Venous blood specimens were collected in EDTA tubes, centrifuged immediately for plasma separation then kept frozen at -20?C until analysis. Plasma estradiol, progesterone, and prolactin levels were assayed [17-19] by enzyme immunoassay test (ELISA, BioCheck, Inc, USA) using universal micro plate reader (ELx800, USA). Progesterone and Estrogen receptors were assayed by DakoCytomation CA (USA).

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the statistical package for the social science SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc Chicago, IL) statistical program. Results were expressed as mean ? ES, t-test was used to compare the significance of the mean differences between two groups. The differences were considered significant if the obtained P value was less than or equal to (0.05).

Results

One hundred and forty cancerous and benign females were in this study. Eighty three females were breast cancer and fifty seven were benign patients.

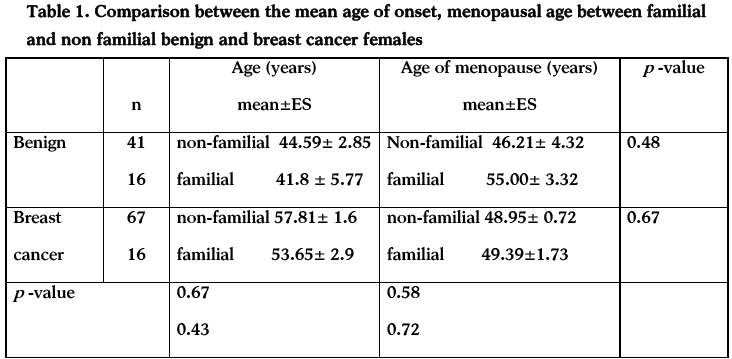

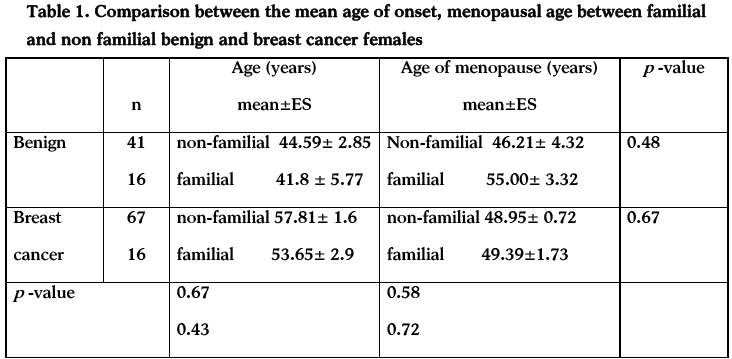

No statistical differences were found between the mean age of onset of familial benign (41.8 ± 5.77) compared to familial breast cancer (53.65± 2.9) (table 1). Also no statistical differences were found between the mean menopause age of familial benign females (55.00± 3.32) compared to the familial breast cancer (49.39±1.73).

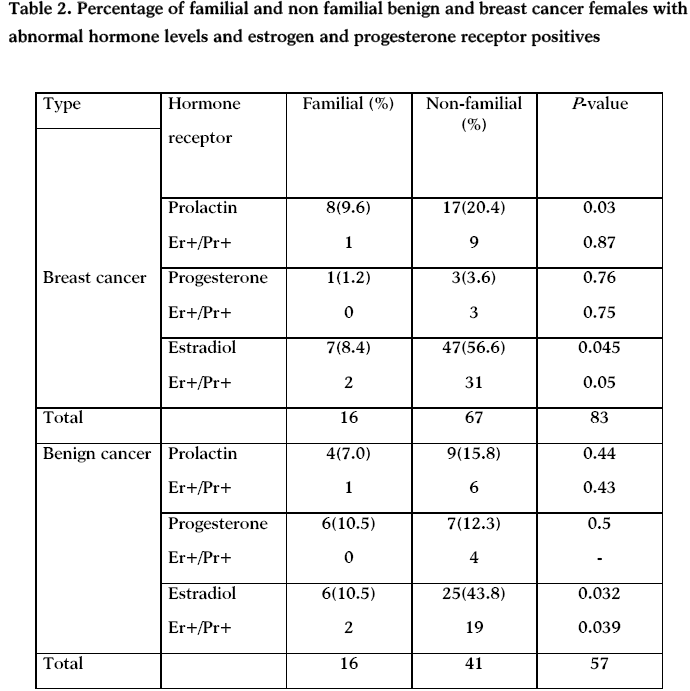

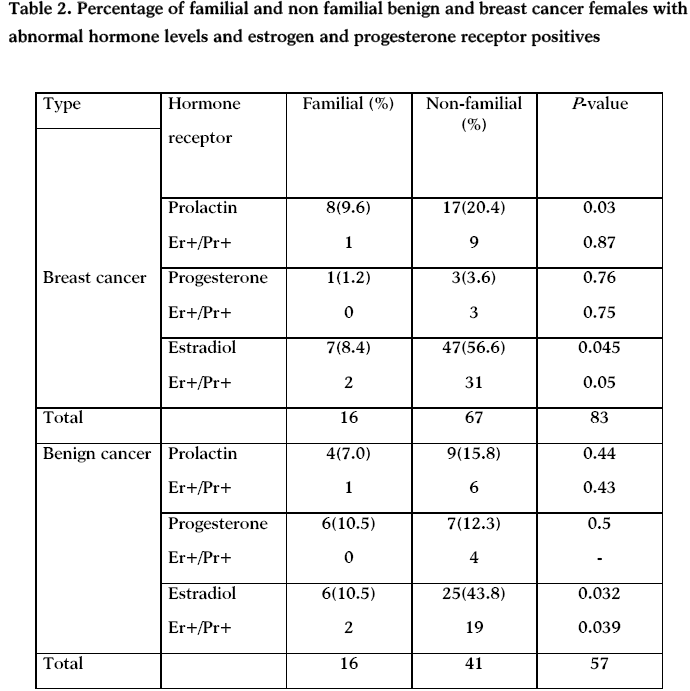

About fifty seven percent of non-familial breast cancer females have abnormal estradiol and about twenty percent have abnormal prolactin. On the hand, about eight and ten percent of familial breast cancer have abnormal estradiol and prolactin. The same trend appears on benign in cancer; plasma levels of estradiol, progesterone among non-familial females were forty four percent and twelve percent, respectively. On the other hand about sixteen percent of benign cancers have abnormal prolactin (table 2).

Estrogen and progesterone positive receptors were statistically significant among benign, breast familial and non-familial cancers with high estradiol (p=.039).

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer overall as well as the most common malignancy afflicting women in Jordan. According to the latest statistics from the Jordan National Cancer Registry, breast cancer ranked first among cancer in females, accounting for 36.7% of all female cancers, and is the leading cause of cancer deaths among Jordanian women [20].

Our study showed that familial breast cancer occurs at earlier age compared to non-familial (table 2), but, there is no statistical differences between mean ages of cancer onset among postmenopausal familial and non-familial breast cancer and benign females. Typically, young women present with more benign pathologies, especially in those harboring familial predisposition for breast cancer and this risk declined among older females [21].

There is marked and consistent association between late age of menopause and breast cancer risk [22]. For women with menopause below 40 years, the risk of developing breast cancer was about 50% that of women with menopause over age 50 [23]. In Jordan, Jordanian women are afflicted with breast cancer (median age is 51) at a much younger age than women in Western countries (median age is 65), when they are still raising children [20]. Jordanian breast cancer median age is close to menopausal age which is ranging between 46.21± 4.32 non-familial and 55.00± 3.32 familial benign and 48.95± 0.72 non-familial and 49.39±1.73 familial breast cancer (table 1). Although early onset breast cancer represents inherited effects on immature mammary epithelium, while late-onset breast cancer likely follow extended exposures to promoting stimuli like plasma hormones of susceptible epithelium that has failed to age normally [24]. Our data showed no statistical difference between menopausal age among familial and non-familial benign females.

The key finding of the present study is that non-familial benign and breast cancer seems to be a hormonal dependent, females with abnormal hormones are (41/57=71.9%) (67/83= 88.7%) for benign and breast cancer, respectively as shown in table (2). Most non-familial breast cancer patients had either high plasma levels of estradiol, or prolactin, while benign breast cancers had increased plasma levels of estradiol, progesterone or prolactin indicating that these hormones may be implicated in a number of ways in breast cancer development. These results support the lines of evidence which suggests the role of these hormones in breast cancer [25-29]. Estrogen and progesterone may be mediated through steroid hormone receptor expression, or through cell cycle proteins: p21,p27 and cyclin D1. However, prolactin may be mediated through modulation of membrane receptors [30].

Cancer that is hormone-sensitive is slightly slower growing and has a better chance of responding to hormone-suppression treatment, than cancer that is hormone receptor negative. Gene expression profiling studies have shown that estrogen receptor positive and estrogen negative breast cancers are distinct diseases at the transcriptomic level, that additional molecular subtypes might exist within these groups, and that the prognosis of patients with estrogen positive disease is largely determined by the expression of proliferation-related genes. Our data shows that most non familial benign and breast cancers have abnormal estradiol, prolactin and are estrogen and progesterone receptor positive.

Our data shows that hormonal factors have low roles in the development that familial breast cancer. This may be due to the fact that about fifty percent of familial breast cancer caused by either highly penetrant genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2 , or by low penetrant genes like PALB2, BRIP1, ATM, NBS1, RAD50, CHEK2, P53 and PTEN2. The other 50% may be caused by unidentified genes.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks for King Hussein Medical Center (Amman-Jordan) where part of this work has been carried out, and special thanks for all participating females who enrolled in this study, and to Dr. foad Zoughool for his technical assistances in plasma hormone analysis. This work was financially supported from Hashemite University (grant number 55/2005), Jordan.

3128

References

- Katapodi MC, Aouizerat BE. Do women in the community recognize hereditary and sporadic breast cancer risk factors. Oncology Nursing Forum 2005; 32, (3): 617-623.

- Slijepcevic P. Familial breast cancer: recent advances, ActaMedicaAcademica 2009; 36:38-43.

- Steiner E, Klubert D, Knuston D. Assessing breast cancer risk inwomen, Am Fam Physician 2008; 78(12):1361-6.

- Yu H, Shu XO, Shi R, Dai Q, Jin F, Gao YT, Li BD, Zheng W. Plasma sex steroid hormones and breast cancer risk in Chinese women, Int J Cancer 2003; 105(1): 92-97.

- Nelson LR, Bulun SE. Estrogen production and action. J Am AcadDermatol 2001; 45:116- 24.

- Henderson BE, Feigelson HS. Hormonal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2000; 21: 427-433.

- Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormones and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Breast Dis 2005; 24:3-15.

- Hankinson SE, Eliassen AH. Endogenous estrogen, testosterone and progesterone levels in relation to breast cancer risk. J Steroid BiochemmolBiol 2007; 106: 1-5.

- Goffin V, Binart N, touraine P, Kelly PA. Prolactin: the new biology of an old hormone. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002; 64: 47-67.

- Clevenger CV, Furth PA, Hankinson Schuler LA. The role of prolactin in mammary carcinoma. Endcr Rev. 2003; 24: 1-27.

- Manjer J, Johansson R, Berglund G,Janzon L, Kaaks R, Agren A, Lenner P. Postmenopausal breast cancer risk in relation to sex steroid hormones, prolactin and SHBG. Cancer Cause Control 2003; 14: 599-607.

- Tworoger SS, Sluss P, Hankinson SE. Association between plasma prolactin concentration and risk of breast cancer among predominantly premenopausal women. Cancer Res. 2006; 66: 2476-2482.

- Lanari C, Molinolo AA. Progesterone receptors-animal models and cell signaling in breast cancer. Diverse activating pathways for the progesterone receptor; possible implications for breast biology and cancer. Breast cancer Res 2002; 4: 240-243.

- Campagnoli C, Clavelchapelon F, Kaaks R, Peris C, Berrino F Progestins and progesterone in hormone replacement therapy and the risk of breast cancer. J steroid BiochemMolbiol 2005; 96,: 95-108.

- Wysowski DK, Comstock GW, Helsing KJ et al. Sex hormone levels in serum in relation to the development of breast cancer Am J Epidemiol 1987; 125: 791-799.

- Helzlsouer KJ, AlbergAj, Bush TL, Longcope C, Gordon GB,Comstock GW. A prospective study of endogenous hormones and breast cancer. Cancer detectPrev 1994; 18: 79-85.

- Sitruk-Ware R. Progestogen in hormonal replacement therapy new molecules, risks and benefits. Menopause: J North Am Menopause Soc 2002; 9: 6-15.

- Joshi UM, Shah HP, Sudhama SP. A sensitive and specific enzyme immunoassay for serum testosterone Steroids 1979; 34:35.

- Tietz, NW. Clinical Guide to Laboratory Tests, 3rd edition, W.B. Sannders, Co. Philadelphia 1995; 509-512.

- Meisner AL, Fekrazad MH, Royce ME. Breast disease benign and malignant 2008; 92 (5):1115-1141.

- Collaborative group on hormonal factors in breast cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy. Collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Lancet 1997; 350: 1047-1059.

- Chang Claude J, Andrieu N, Matti R, Richard B, Antonis CA, Susan P, et al. Age at menarche and menopause and breast cancer risk in the international BRCA1/2 carrier cohort study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 2007;16: 740-756.

- Benz CC. Impact of aging on the biology of breast cancer, Crit Rev OncolHematol 2008; 66(1): 65-74.

- Fourkala EO, Zaikin A, Burnell M, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ford J, Gunu R, et al. Association of serum sex steroid receptor bioactivity and sex steroid hormones with breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. EndocrRelat Cancer. 2011; Dec 23. [Epub ahead of print]

- Clevenger CV, Chang WP, Ngo W, Pasha TL, Montone KT, Tomaszewski JE. Expression of prolactin receptor in human breast carcinoma. Evidence for an autocrine / paracrine loop. Am J Pathol 1995;146 (3): 695-705.

- Ginsburg E and VonderHaar BK. Prolactin synthesis and secretion by human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 1995; 55(12): 2591-5.

- Abdelmagid SA, Too CK. Prolactin and estrogen up-regulate carboxypeptidase-d to promote nitric oxide production and survival of mcf-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 2008; 149(10): 4821-4828.

- Hielala M, Olsson H, Jernstrom H. Prolactin levels, breast feeding and milk production in a cohort of young healthy women from high risk breast cancer families: implications for breast cancer risk. Fam Cancer 2008; 7(3): 221-228.

- Fosti A, Jin Q, Grzybowska E, Soderberg M, Zientek H, Sieminska M, et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin polymorphism in familial and sporadic breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 2002; 23(8): 1315-1320.