Santoshkumar Abujam1*, Ram Kumar1, Achom Darshan2, Budhin Gogoi1 and Debangshu Narayan Das1

1Fishery and Aquatic Biology Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills, Doimukh, India

2Centre with Potential for Excellence in Biodiversity, Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hills, Doimukh, India

Corresponding Author:

Santoshkumar Abujam

Fishery and Aquatic Biology Laboratory

Department of Zoology, Rajiv Gandhi University

Rono Hills, Doimukh, India

Tel: 09401479699

E-mail: santosh.abujam@gmail.com

Received Date: 31.07.2017; Accepted Date: 22.08.2017; Published Date: 24.08.2017

Citation: Mbamalu ON, Antunes E, Silosini N, Samsodien H, Syce J (2016) HPLC Determination of Selected Flavonoid Glycosides and their Corresponding Aglycones in Sutherlandia frutescens Materials. Med Aromat Plants 5:246. doi:10.4172/2167-0412.1000246

Copyright: © 2016 Mbamalu ON, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Keywords

Fish diversity; Livelihood; Tezu river; Arunachal Pradesh, India

Introduction

The state of Arunachal Pradesh is the biggest among the northeastern states of India in terms of physical area as well as in river basins and refuge of varied fish species. The Indian north-eastern regions are the hot spots of biodiversity in the world (Kottelat and Whitten, 1996). Still, many of them are un-described and numbers of species are under the different category of IUCN red list. Moreover, there are many water bodies which are still unexplored due to dense forests, steep terrains and poor communication. Hence, the discovery of the fish species from these water bodies has not been fully explored till now which might be new to the science. However, the various notable workers partially studied the fish diversity of Arunachal Pradesh, namely Sen (1999) reported 52 fish species from Siang and Subansiri districts; Nath and Dey (2000) listed 131 species; Sen (2006) scanned 143 species; Tamang et al. (2007) listed 47 species; Bagra et al. (2009) recorded 213 fish species from 35 rivers; Bagra and Das (2010) enumerated 44 fish species. Recently, Kumar et al. (2016) cataloged 42 fish species from the sinkin river in Lower Dibang valley of Arunachal Pradesh.

As far as the socio-economic status of fishermen in Arunachal Pradesh is concerned, it was very limited. As per literature, researchers and notable workers have not properly studied or investigated on the livelihood of the fishermen in the state till now. However, more recently Kumar et al. (2016) quested the socioeconomic dependence of the local tribal and fishermen residing in and around of Sinkin River in Lower Dibang Valley district of the state. Therefore, from the above drawbacks, an attempt has been made to explore/investigate on the fish diversity and livelihood of fishermen at the Tezu river in Lohit district, Arunachal Pradesh, India.

Materials and Methods

Study area, period and methodology

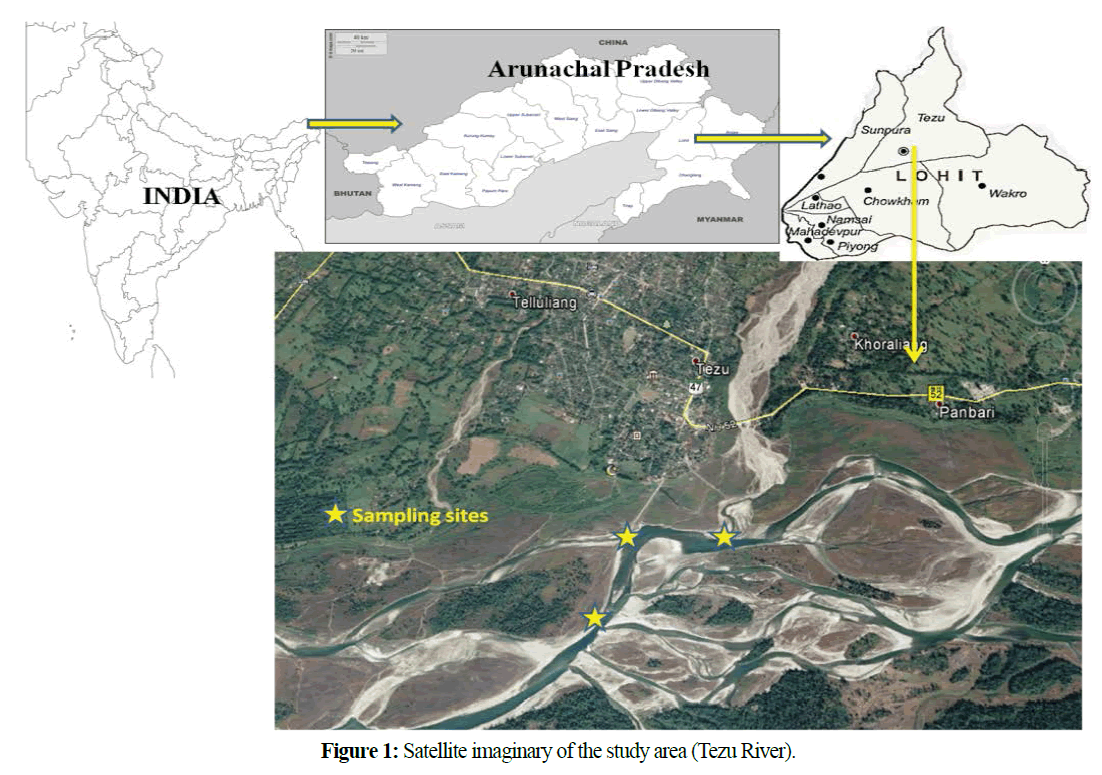

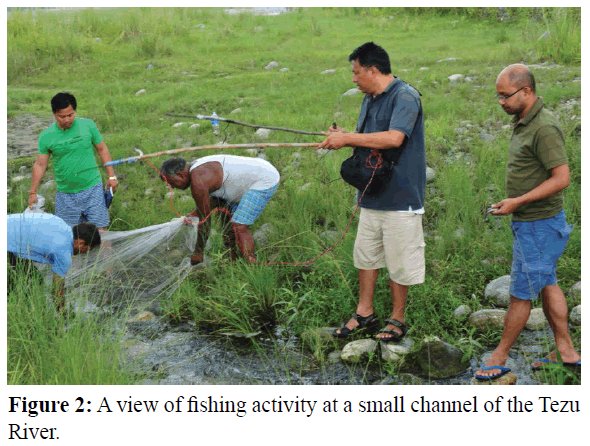

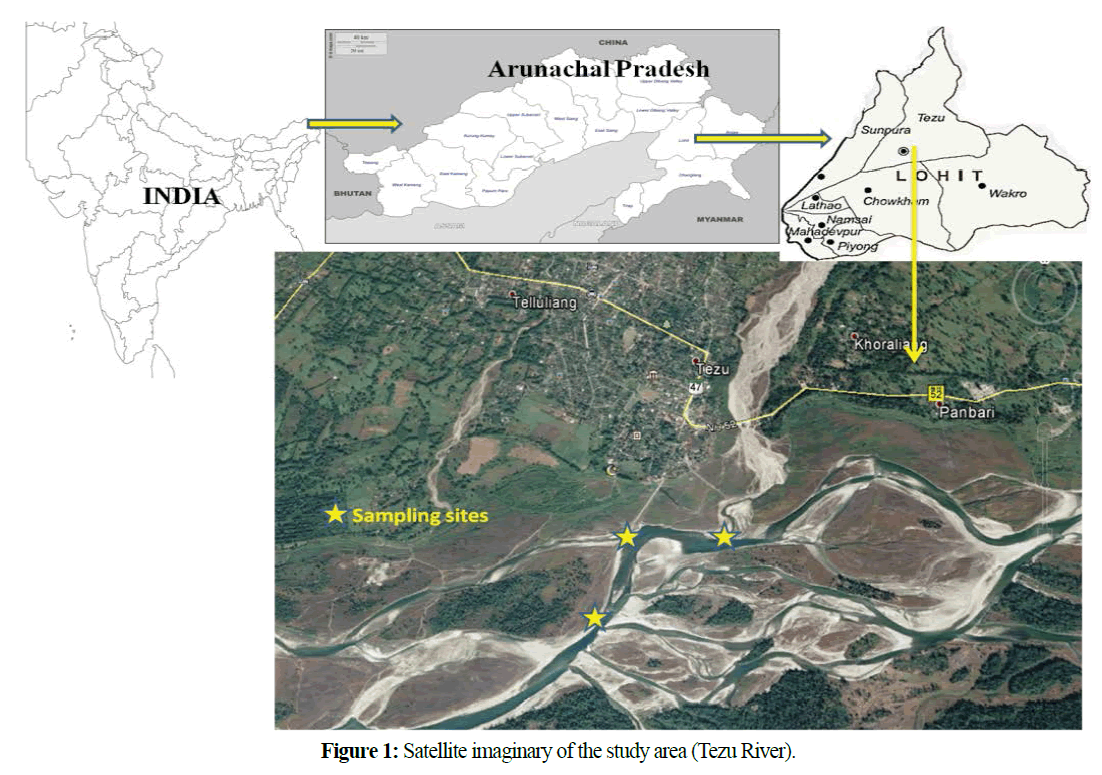

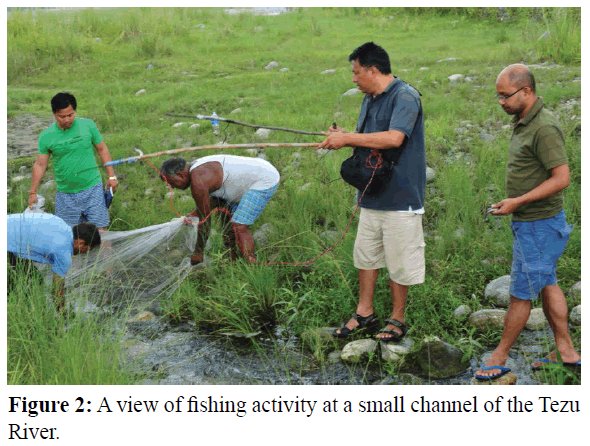

A contemporary study was executed from the Tezu river (nallah) at Tezu in Lohit district of Arunachal Pradesh, India from August, 2016 to March, 2017 (Figure 1). The three sampling site were selected for this task and marked as site I (27°54’ 30.34” N and 96°10’16.71” E), II (27°54’31.01”N and 96°09’54.65”E) and III (27°54’12.83”N and 96°09’47.52”E). Seasonal data collection and sampling was done from Tezu river (nallah) and its tributary namely Dus nallah. The river is joined by several small channels after flowing downstream about 10 km and it again joins with the Lohit river, finally drained into the Brahmaputra River. The fish species were fixed using cast net and electro-fishing from the respective sampling sites (Figure 2) and further, the specimens were preserved in 5% formalin for identification. The specimens were identified by following the standard keys of Talwar and Jhingran (1991) and Vishwanath et al. (2007). The conservation status of the listed fish species were also assessed through IUCN, 2017-1.

Figure 1: Satellite imaginary of the study area (Tezu River).

Figure 2: A view of fishing activity at a small channel of the Tezu River.

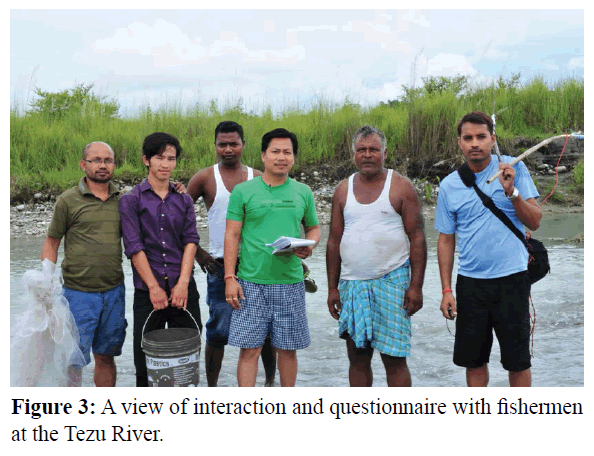

Livelihoods of the fishermen were investigated based on the written specific questions and through individual (fishermen) interview (Figure 3). The information provided by the fishermen were analysed and gathered the availabilities of fish in the river and small streams. The household characteristics such as type of family, size of family, educational status, land use pattern, occupation, annual income, status of fisheries etc., were included in the written questionnaire. Moreover, the propaganda on traditional fisheries management (Fisheries Regulations Act, village regulation, penalty imposed etc.), fishing tools and techniques were also compiled through instant interaction with the village chief and aged person. The respondents were thoroughly assured with the information obtained would not prejudice them in any case.

Figure 3: A view of interaction and questionnaire with fishermen at the Tezu River.

Physical characterization of Tezu nallah (River)

The Tezu River is waggling shaped with some pools at an extent. Naturally, the bottom of the river is filled with silt, sand, boulders etc. and the small channels filled with gravel and cobbles. The logs and large woody debris in the river were occasionally found and the organic materials (leaves and twigs) were infrequently occurred in the streams. The approximate depth of the river was 2-3 ft and 5-6 ft at pool areas whereas, the estimated width of the river was 600-650 ft. Stream velocity of the sampling sites was recorded as 1.1-1.2 m/s. The shape of the river was expanded and deep-seated at some extent. The riverine zone (water’s edge and stream bank) of the river was covered by boulder, gravel, bushes, shrubs, tall grasses etc. on both sides. It was noticed that the bank of the upstream was collapsed or eroded on both sides in every rainy season. There is a small barren island in the middle of the river where the sampling was done and the water heads bifurcates at large extent covering the island and again joined together.

Results and Discussion

Fish diversity of Tezu River and its drainages

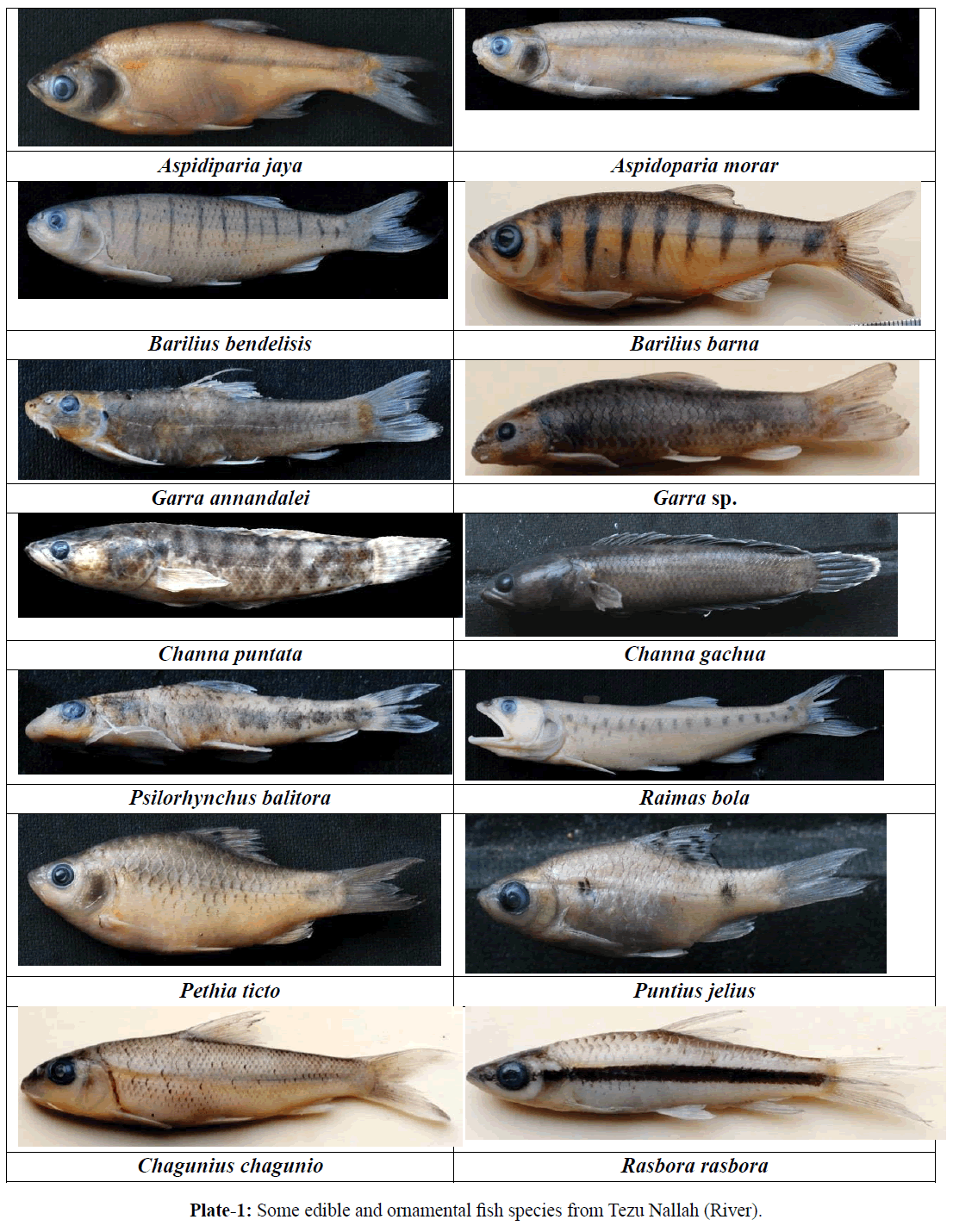

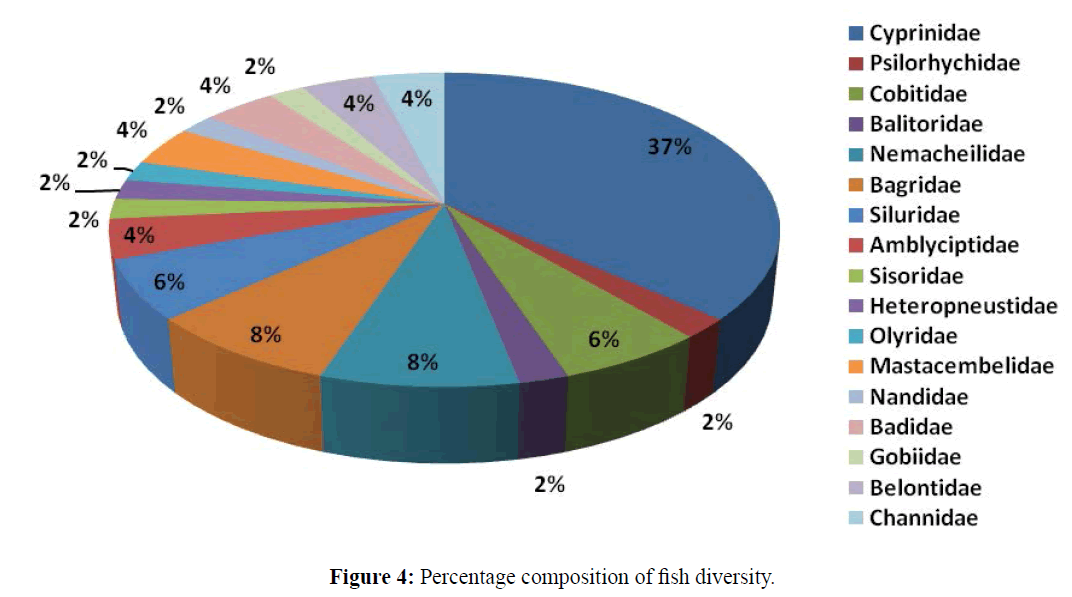

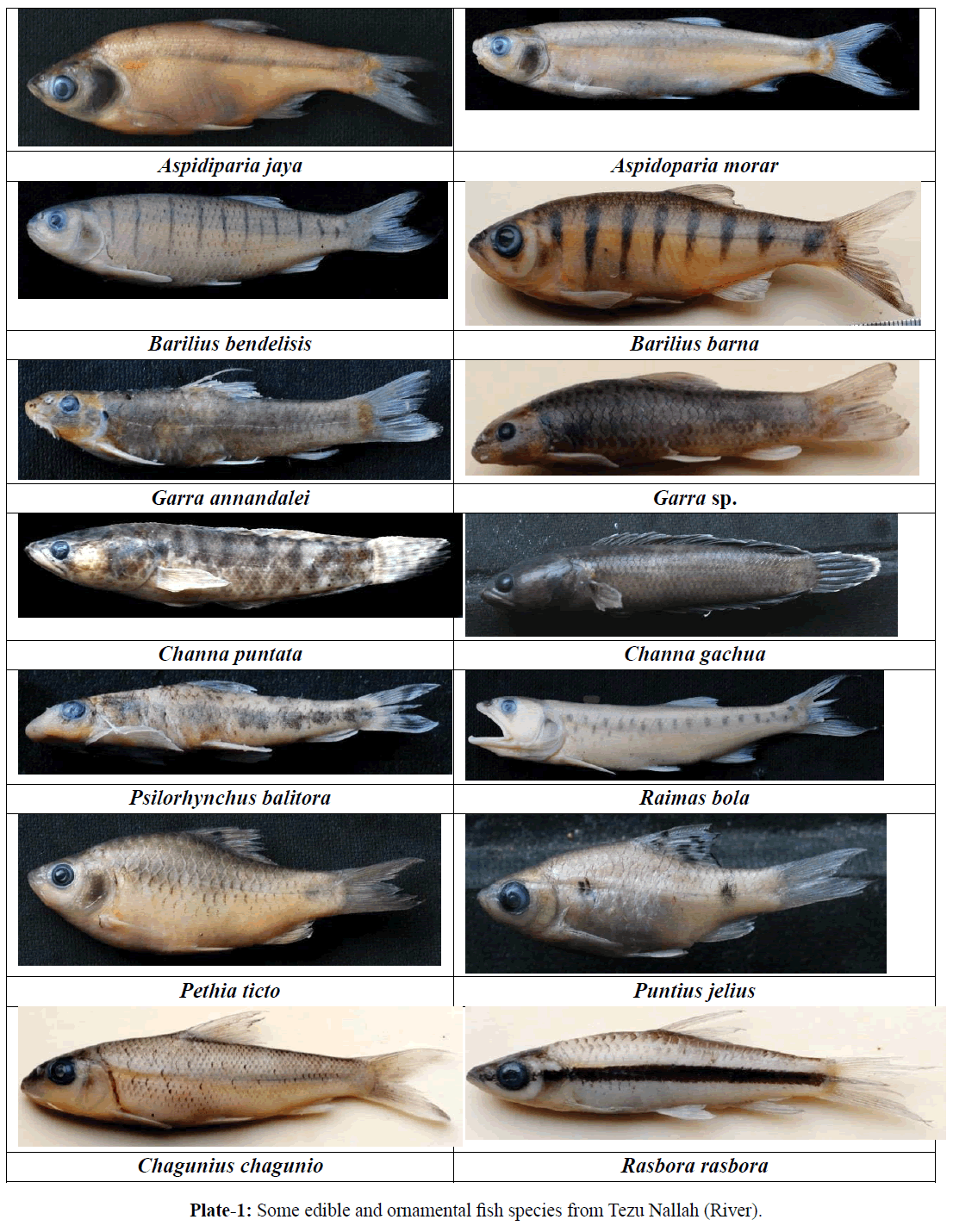

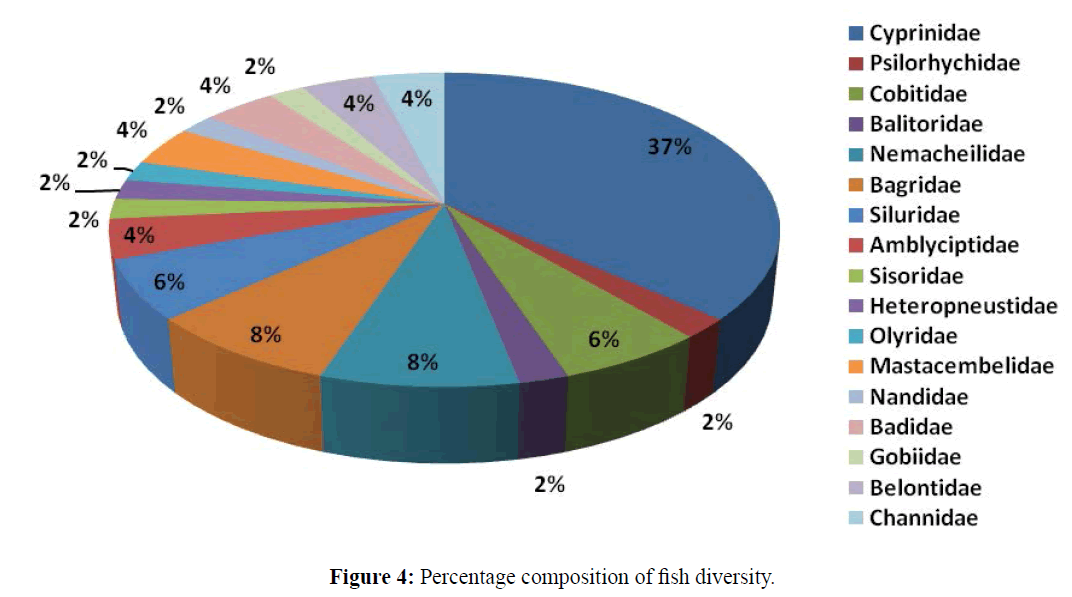

Totally 49 fish species has been listed under 33 genera and 17 families (Table 1 and Plates 1-3). It was contemplated among the families, Cyprinidae was the foremost which accommodated 18 species accounting 36.73% (Figure 4). Next followed by Nemacheilidae and Bagridae with 4 species each and holding 16.33%; Cobitidae and Siluridae with 3 species each and accounting 12.25%. These are further followed by Amblyciptidae, Mastacembelidae, Badidae, Belontidae and Chandidae comprising 2 species each accounting 20.4%. Other families like Psilorhychidae, Balitoridae, Sisoridae, Heteropneustidae, Olyridae, Nandidae and Gobiidae with 1 species each and accounting 14.29%. The present observation was similar with the findings of Bagra et al. (2009); Bagra and Das (2010); Das et al. (2015), Kumar et al. (2016) where the Cyprinidae family was dominated in the different rivers of the state. In fact, the diversity of fish might vary from drainage to drainage due to its topographical variations.

| Family |

Sl.No. |

Scientific name |

IUCN Status |

| Cyprinidae |

1 |

Aspidopariajaya |

NE |

| |

2 |

Aspidopariamorar |

LC |

| 3 |

Bariliusbendelisis |

LC |

| 4 |

Bariliusbarna |

LC |

| 5 |

Labeogonius |

LC |

| 6 |

Raimas bola |

LC |

| 7 |

Banganadero |

LC |

| 8 |

Chaguniuschagunio |

LC |

| 9 |

Crossocheiluslatius |

LC |

| 10 |

Garraannandalei |

LC |

| 11 |

Garra sp. |

NE |

| 12 |

Devarioaequipinatus |

LC |

| 13 |

Devario sp. |

NE |

| 14 |

Rasborarasbora |

LC |

| 15 |

Puntiussarana |

LC |

| 16 |

Puntiussophore |

LC |

| 17 |

Pethiaticto |

LC |

| 18 |

Pethiajelius |

LC |

| Psilorhychidae |

19 |

Psilorhynchusbalitora |

LC |

| Cobitidae |

20 |

Botiarostrata |

VU |

| 21 |

Lepidocephalichthysguntea |

LC |

| 22 |

Lepidocephalichthysarunachlaensis |

EN |

| Balitoridae |

23 |

Balitorabrucei |

NT |

| Nemacheilidae |

24 |

Schisturasp.1 |

NE |

| 25 |

Schisturasp.2 |

NE |

| 26 |

Aborichthys sp. |

NE |

| 27 |

Acanthocobitisbotia |

LC |

| Bagridae |

28 |

Mystusdibrugarensis |

LC |

| 29 |

Mystustengra |

LC |

| 30 |

Mystusbleekeri |

LC |

| 31 |

Batasiobatasio |

LC |

| Siluridae |

32 |

Ompokpabo |

NT |

| 33 |

Ompokpabda |

NT |

| 34 |

Kryptopterusindicus |

DD |

| Amblyciptidae |

35 |

Amblycepsapangi |

LC |

| 36 |

Amblycepsarunachalensis |

NE |

| Sisoridae |

37 |

Gagatacenia |

LC |

| Heteropneustidae |

38 |

Heteropneustesfossilis |

LC |

| Olyridae |

39 |

Olyralongicaudata |

LC |

| Mastacembelidae |

40 |

Macrognathuspancalus |

LC |

| 41 |

Macrognathusaral |

LC |

| Nandidae |

42 |

Nandusnandus |

LC |

| Badidae |

43 |

Badisassamensis |

DD |

| 44 |

Badisbadis |

LC |

| Gobiidae |

45 |

Glossogobiusguiris |

LC |

| Belontidae |

46 |

Trichogasterchuna |

LC |

| 47 |

Trichogasterfasciata |

LC |

| Channidae |

48 |

Channapunctata |

LC |

| 49 |

Channagachua |

LC |

Legend: LC=Least Concerned; V=Vulnerable; NT=Near threatened; DD=Data Deficient; NE=Not evaluated

Table 1: List of fish species and their IUCN status.

Plate 1: Some edible and ornamental fish species from Tezu Nallah (River).

Plate 2: Some edible and ornamental fish species from Tezu Nallah (River).

Plate 3: Some edible and ornamental fish species from Tezu Nallah (River).

Figure 4: Percentage composition of fish diversity.

According to IUCN (2017-1), out of the 49 fish species 35 species fall in Least Concerned (LC) category with 71.4%; 7 species in Not Evaluated (NE) with 14.28%; 3 species in Near Threatened (NT) with 6.12%; 2 species in Data Deficient (DD) with 4.08%; 1 species in Vulnerable (VU) with 2.04% and 1 species in endangered (EN) with 2.04%.

Livelihood (Socio-economic status)

The socio-economic status of fishermen of Tezu nallah (river) at Tezu was investigated and the details given in Table 2. For which, a total of 35 households of fishermen were selected and randomly interviewed. The 35 household profiles represent 190 population consisting 93 females and 97 males. The joint families (100%) were in bulk comprising more than 5 members and none of the families were nuclear. Such average joint families needed more or less higher income for their alimentation. Out of the 35 households, only 25 fishermen have been engaged actively in fishing activity. The age of the fishermen was found 28% for up to 25 years; 60% for up to 60 years and 12% for up to 60 years. The literacy rate was noted as 21.05% (as illiterate); 42.10% (as primary level); 21.05% (as high school level); 15.80% (as higher secondary) and there was no record of graduation level. Fishing activity was the main source of income for 71.42% families and daily wages work as 28.58% families. They have no land for agriculture as they have been residing in rented house. The alternative uses of the water bodies was bathing/washing (100%) and for drinking to an extent. The average monthly income was recorded as Rs. 6,000/- with 14.29%; Rs. 10,000/- with 34.29%; and Rs. 10,000/- with 51.42% families. According to respondents (100%), the present status of the fish availability in the areas was also in declining trend. The livelihood of the fishermen was directly or indirectly dependent on catching fishes and their alternative occupation (daily wages work). Indeed, these waterbodies are one of their main sources of income and someway they manage to run the family. Generally, from the age of 25 to 60 years of men has been actively engaged in fishing activities and even some members below 15 years were also engaged in fishing activity along with parents using spears, hooks and multiple forks. It might be acknowledged the respondents (100%) admitted there has been prohibited (banned) all kinds of fishing activity from June to August for conservatory measures.

| Sl.No. |

Parameters |

No. |

% |

| 1 |

Household |

35 |

|

| 2 |

Population |

|

190 |

|

| |

Male |

97 |

51.05 |

| Female |

93 |

48.95 |

| 3 |

Size of family |

Nuclear |

Nil |

-- |

| Joint |

100 |

100 |

| 4 |

No. of fishermen engaged |

Man |

25 |

|

| 5 |

Age of fishermen |

25 years |

7 |

28 |

| |

|

50 years |

15 |

60 |

| 60 years |

3 |

12 |

| 6 |

Educational status |

Illiterate |

40 |

21.05 |

| Primary level |

80 |

42.1 |

| High school level |

40 |

21.05 |

| Higher secondary level |

30 |

15.8 |

| Graduate level |

Nil |

|

| 7 |

Main occupation of household |

Agriculture |

Nil |

|

| Fishing |

25 |

71.42 |

| Other Daily wages work |

10 |

28.58 |

| 8 |

Main use of waterbodies |

Bathing, washing |

|

100 |

| 9 |

Monthly family income (Fishing & Daily wages) |

|

|

|

| |

1. Upto 6,000/- |

5 |

14.29 |

|

| 2. Upto 10,000/- |

12 |

34.29 |

|

| 3. More than 10,000/- |

18 |

51.42 |

|

| 10 |

What is present status of the fisheries? |

|

100 |

| Decrease its production year by year as per their observations. |

Table 2: The household profile of fishermen.

The population of the Tezu area comprised of different indigenous tribes and fishermen including Shahni, Mukhiya and Machuawari community. They are mostly from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh and residing at purana radio centre which is just 0.4 km away from Tezu River (fishing sites). Once, the radio centre was located at the heart of Tezu town which was flown away due to heavy flood and thus the river course direction was also drastically changed. The fishermen have no lands for cultivation and reside in the rented house since two and half decade. In a time, the fishermen use to catch the fish species whole day except fishing banned period (June- August). Now a day, due to decreasing of fish availability they use to catch the fish species only during morning and evening time. Their earning is not enough to run the family hence they earn by doing daily wages work and rickshaw pulling by day time. They also revealed that the availability of diverse fish species is decreasing year by year. Presently, they use to catch the fishes about 3-4 kg/fishermen/day. They also reveal that before 10 years ago, they use to catch the fishes about 10-12 kg/fishermen/day.

Fishing activity is their daily practice in the areas and controlled by these fishermen for not only selling but also for consumption. As fishes are invariably rich in protein food sources for human being and also as a good bio-indicator of the water bodies. They generally use the different gears while catching fishes in the river. Every household possess fishing nets (cast net), basic design of bamboo and other fishing gears (spears, multiple fork, hooks etc.). The indigenous tribes are not involved in the fishing activities. However, during the banned period and winter season, some local tribes occasionally used to catch the fishes by using poisoning, dynamiting and electro fishing methods. Such illegal activities will lead to the declining of the aquatic resources as the period is for breeding, parental care and spawning of the fishes. Usually, the fishermen are paid a minimum amount to the town head (Goanbura) for welfare of the areas. They directly sell the fishes to the Tezu market and to some traders outside the state. The fishermen also reveal that some of the traders from Assam occasionally visited at Tezu and collected live fishes for exporting to Guwahati, Assam and Kolkata, West Bengal. The sustainable management of the aquatic resources is indeed played an important role of livelihood not only for the large section of tribal people but also for the fishermen of the areas.

Conclusion

It is clear from the above discussion, the Lohit River and drainages system has been provided livelihood of the fishermen and also demonstrate a number of ornamental and edible fishes. The indigenous tribal should continue their support to the fishermen and adopt as their alternative source of revenue by exporting trade and supply to other nearby markets in a sustainable way. Proper scientific techniques of fishing would help in the up-gradation of the socio-economic of the fishermen as well as local tribal who are directly or indirectly involved in the fishing activities. A long effective management plan should be adopted for conservation of fishes and illegal fishing should be strictly prohibited. So that the Tezu River may become a commercial hub for ornamental fish trade in future and the Govt. may also organize various programmes for encouraging the formation of fisher’s cooperative society.

Acknowledgement

The first (SKA), second (RK), fourth (BG) and fifth (DND) authors are thankful to Department of Biotechnology, New Delhi, Govt. of India for financial help through DBT Project No. BT/382/ NE/TBP/2012 to carry out the work at the Department of Zoology, Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hill, Arunachal Pradesh, India. The third author (AD) is also thankful to the Centre with Potential for Excellence in Biodiversity (CPEB-II), Rajiv Gandhi University, Rono Hill, Doimukh for fellowship and research facility.

20092

References

- Bagra, K., Das, D.N. (2010) Fish diversity of river Siyom of Arunachal Pradesh; A case study.Our nature 8, 164-169.

- Bagra, K., Kadu, K., Sharma, K.N., Laskar, B.A., Sarkar, U.K., et al. (2009) Icthyological survey and review of checklist of fish fauna of Arunachal Pradesh, India. Check list 5, 330-350.

- Das, B.K., Boruah, P., Kar, D. (2015) Icthyofaunal diversity of Siang River in arunachalpradesh, India.Pro.ZoolSoc p: 1-9.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2015) Red List of Threatened Species IUCN.Version 2015-4.

- Kottelat, M., Whitten, T. (1996) Freshwater biodiversity in Asia with special reference to Fish, World Bank, Technical paper No. 343, Washington, DC pp:17-22.

- Nath, P., Dey, S.C. (2000) Fish and fisheries of North Eastern India (Arunachal Pradesh). New Delhi. Narendra Publishing House pp: 217.

- Kumar, R., Abujam, S.K., Ganguly, A., Das, D.N. (2016) Fish and Fisheries of Sinkin Tributary with Emphasis on the People’s Socio-economic Dependence in Dibang River Basin of Arunachal Pradesh, India.J FishSci.com 10, 70-75.

- Sen, N. (1999) On a collection of fishes from Subansiri and Siang districts of Arunachal Pradesh. Rec ZoolSurv India 97, 141-144.

- Sen, T.K. (2006) Pisces. In: Fauna of Arunachal Pradesh. State fauna Series 13 (Part 1): 317- 396, ZoolSurv India Publication p: 396.

- Talwar, P.K., Jhingran, A.G. (1991) Inland fishes of the India and adjacent countries. Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. New Delhi p: 541.

- Tamang, L., Chaudhury, S., Chodhury, D. (2007) Icthyofaunal contribution to the state and comparison of habitat contiguity on taxonomic diversity in Senkhi stream, Arunachal Pradesh, India. J. Bombay Nat HistSoc104, 170-177.

- Vishwanath, W., Lakra, W.S., Sarkar, U.K. (2007) Fishes of North East India, NBFGR.Lucknow, U.P. India p: 264.