Keywords

Indiginous practice; Local people; Medicinal plants; Traditional medicine; Wonch district

Abbreviations: IK: Indigenous Knowledge; MM; Modern Medicine; MP: Medicinal Plants; TMPU: Traditional Medicinal Plant Use

Introduction

According to WHO [1], consultation of medicinal practitioners is very helpful for the development and incorporation of useful approaches in planning and budgeting system for health care provision of most developing nations and indigenous communities. In Africa, traditional medicine plays a central role in health care needs of rural people and urban poor. Here, it is said that, this situation would remain so long as modern medicine continues to be unable to meet the health care of the people of the continent effectively [2]. The value and role of this health care system will not diminish in the future, because they are both culturally viable and expected to remain affordable, while the modern health care service is both limited and expensive [1].

Indigenous traditional medicinal practices were carried out essentially based on private practice, i.e. private agreement between consenting parties, and the knowledge of traditional practice in most cases has descended through oral folk lore [3]. The secret information retained by traditional healers is relatively less susceptible to distortion but less accessible to the public. However, the knowledge is dynamic as the practitioners make every effort to widen their scope by reciprocal exchange of limited information with each other [4].

Incomplete coverage of modern medical system, shortage of pharmaceuticals and unaffordable prices of modern drugs, make the majority of Ethiopian still to depend on traditional plant medicines [4,5]. Hence the present study was initiated to investigate the indigenous practice of traditional plant medicine use among local communities of Wonch District, Western Ethiopia.

Statement of the problem

Traditional medicine is an ancient form of health care practices long before appearance of scientific medicine which have played and continue to have important role in providing curative services to very large number of people particularly in the rural areas of almost all countries of Africa [6]. It is the culture of many people because of its accessibility to the people even in most remote areas particularly in the community where care is given at low cost to patients in their home. Most people have good attitude towards traditional plant medicine, although it is not always the best form of health care system [6].

In many parts of Ethiopia, considerable numbers of research have been done on those practice of traditional plant medicine [7]. Like in other parts of country, in the current study area, the knowledge on medicinal plants depth and width become lesser and lesser due to its secrecy, unwillingness of young generation to gain the knowledge, influence of modern education, religious and awareness factors, which all results in gradual disappearance of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants (Researcher long term direct observation). But there was no much formal research work that had been done on the indigenous practice of traditional plant medicine in the study area. Therefore, this study was aimed to document the traditional medicinal plant species practices in the study area.

Materials and Methods

Descriptions of the study area and location

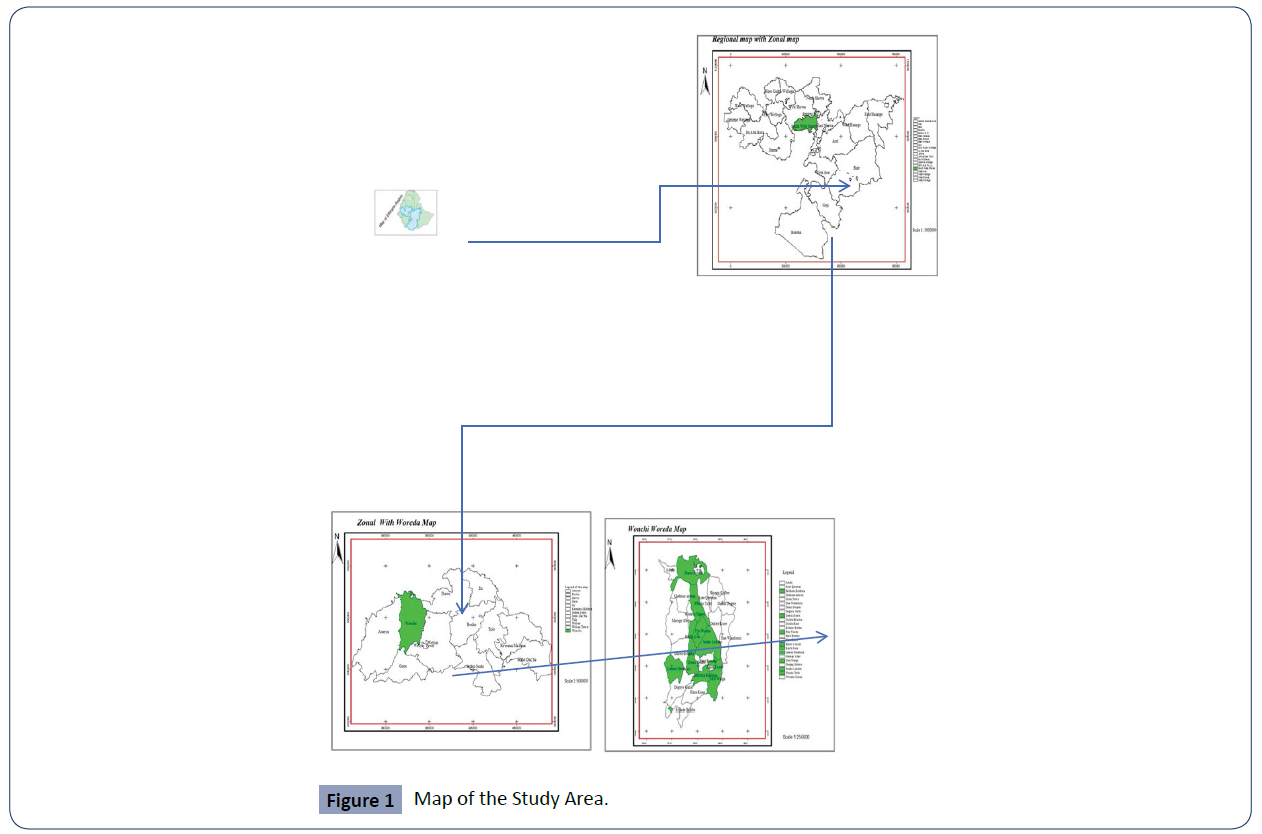

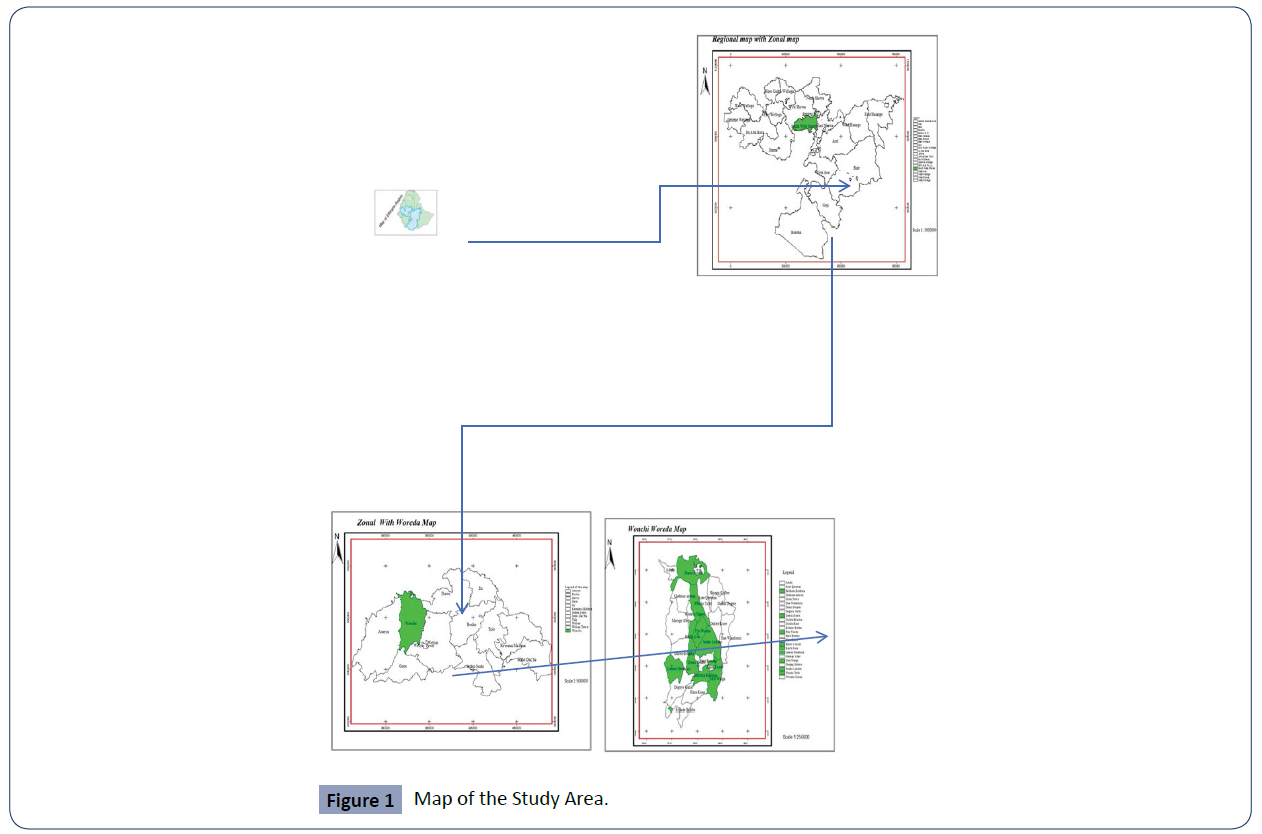

Wonchi District is one of the Districts in the Southwest Shoa Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia, which is located 124 km away from southwest of Addis Ababa with the area coverage of 460,516 hectare and the altitude range between 1798m to 2118m above sea level. The administrative center of Wonchi is Chitu and it has beautyfull Creator Lake known as Wonchi Lake from which the district has got its name. As a result many tourists from inside and outside visit this natural lake every year and it is source of income for the country.

Population

Demographically the district has a population of 119, 736 with almost equal gender ratio of 49.8% male and 50.2% female.

The average family size is 6 and the average number of children perhousehold was nearly 4 indicating that it is found to focus of development intervention addressing child wellbeing to bring real development in the community. Religion wise, Orthodox constitute 58.9%, Protestants 39.6% and Muslims constitute 1.3% while the ethnic group composition, as per the Terminal evaluation findings of 2013, more than 99% are Oromo, the remaining being Amhara, Gurage and others.

Climate

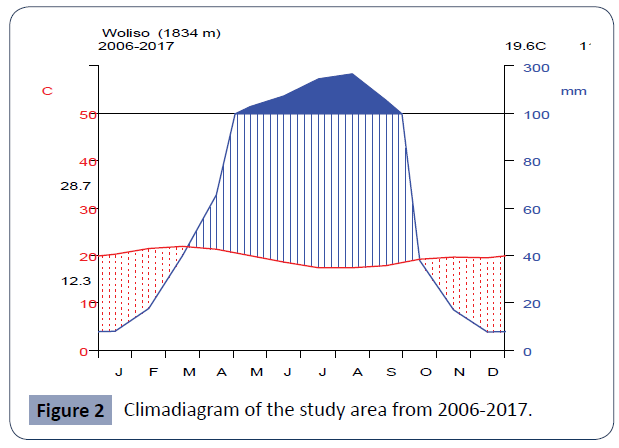

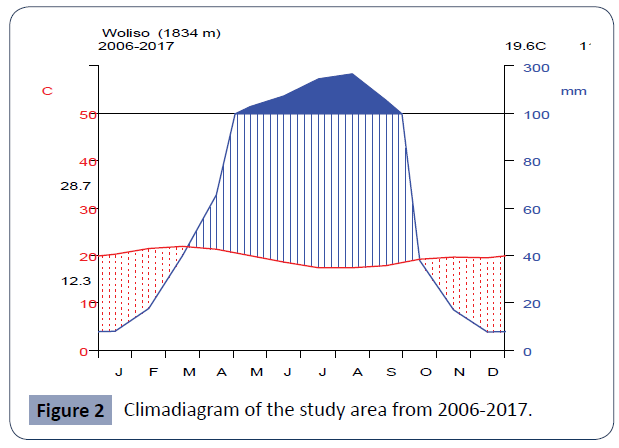

Ecologically the district is divided in to dega or high land (40%) and woina dega or mini land (60%). The mean annual rain fall of the area ranges from 1650-1800 mm with annual temperature range of 10-30°C and mean average of 19.6°C. The study area had 28.7°C annual mean maximum and, 19.6°C annual mean minimum temperature. The annual mean maximum and minimum temperature were recorded in March and November respectively. The highest rainfall distributions occur from June to September (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Map of the Study Area.

Figure 2 Climadiagram of the study area from 2006-2017.

Land use types

Out of the total areas of the District, 82% is cultivated land, 11.7% grazing land, 8.9% covered by natural forest, 1.03% is water body while others is 18.6%.

Vegetation of the study area

Due to variation in altitude and topographical features, the wonchi district vegetation shows three different zones, namely: Afromontane forest, sub alpine and afroalipine) vegetation [8]. The common plant species of the study area include: Achyranthes aspera, Albizia schimperiana, Alchemilla pedata, Apodytes dimidiata, Bruceaantidysenterica, Dombeya torrida, Embelia schimperi, Erica arborea,Festuca gilbertiana, Lobelia rhynchopetalum, Hagenia abyssinica, Hypericum revolutum, Jasminum abyssinicum, Juniperus procera, Kniphofia foliosa, Lobelia giberroa, Maytenus arbutifolia, Millettia ferruginea, Nuxia congesta, Olea capensis, Olea europaea subsp. caspidata, Papaneasimensis, Pittosporum viridiflorum, Prunus africana, Phytolacadodicandra, Salix subserrata, Schefflera abyssinica, Thymus schimperi and Zehneria scabra Vegetation.

Study design

Field survey design was employed together information on the indigenous knowledge, attitude and practice of traditional plant medicine of the local people in the study area. During the survey, both qualitative (none numerical) and quantitative (numerical) data were collected.

Reconnaissance surveys

Preliminary survey was conducted from march 20- 25, 2018. During the preliminary survey general information about the study area were gathered. Based on the information sampling technique, Sampled Kebeles, number of informants and study sites were determined.

Study site selection

From a total 23 Kebeles in the District, nine study Kebeles were selected purposively based on availability of key informants following the recommendation of government officials, stakeholders, and religious leaders during reconnaissance survey. The sampled Kebeles are (Belbela, Dimtu, Fite, Haro wanch, Kurfo gute, Lemen meta hora, Miti welga, Sonkole kake, Waldo telfa).

Informant selection

A total of 198 informants were selected. From these 27 were key informants (3 informants per Kebele) which were selected purposively and 171 (19 per Kebele) of them were general informants which were selected randomly (simple random sampling technique following lottery method). Age range of informants selected for the study were from 20 to 80 who lived 5 year and above in the study area. According to Jarso belay [9], the size of the sample depends on the available fund, time and other reasons and not necessarily depends on total population.

Data collection method

Semi-structured interview, observation and guided field walks with informants were employed to obtain ethnobotanical data as used. Interview was based on a checklist of questions prepared beforehand in English and translated to local languages. Information regarding indigenous practice of local community towards traditional plant medicine of healers was recorded at the spot. Guided field observation was made on the medinal plants to cheek the availability of the plant in the area, to know the habit and habitat of the plant. Focus group discussion was also made to get more information on medicinal plants practice.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data on medicinal plants use and associated indiginous knowledge of local community, their attitude on traditional plant medicine use and medicinal plant used by traditional plant medicine healers of the study area. The results were displayed and summarized in tables and figures by using percentage, frequency and texts. The most useful information gathered on medicinal plants which were analyzed through the descriptive statistics include application, methods of preparation, route of application, disease treated, and parts used and the habit of the plant.

Results and Discussion

Socio-demographic characterstics of respondent’s

A total of 198 informants including 27 key informants were selected. As pointed out by Martin (1995), the selection of key informants is commonly systematic. Most of the respondents (77.77%) were males (Table 1). The majority of respondent’s age range was from 40-60(51.5%). Most of the participants (86.86%) were married (Table 1). Almost all religious leader respondents were followers of Orthodox Christian. From all respondents 33.83% were able to read and write. Number of farmers’ respondents predominated (33.33%) other respondents while NGO workers are lower in number (5.05%) (Table 1).

| No |

Variables |

Response option |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| 1. |

Sex |

Male |

154 |

77.77 |

| Female |

44 |

22.23 |

| Total |

198 |

100 |

| 2. |

Age |

20-40 |

14 |

7.07 |

| 41-60 |

102 |

51.51 |

| 61-80 |

82 |

41.41 |

| 3. |

Marital status |

Single |

12 |

6.06 |

| Married |

171 |

86.86 |

| Windowed |

15 |

7.57 |

| 4. |

Religion |

Christian |

142 |

71.71 |

| Muslim |

27 |

13.63 |

| Waqefata |

25 |

12.62 |

| Others |

4 |

2.02 |

| 5. |

Education |

Uneducated |

41 |

20.70 |

| Able to read and write |

67 |

33.83 |

| 12 complete |

10 |

5.05 |

| 10 complete |

38 |

19.19 |

| Diploma |

39 |

19.69 |

| Degree |

3 |

1.51 |

| 6. |

Occupational status. |

Farmers |

66 |

33.33 |

| Merchants |

25 |

12.62 |

| Government employer |

36 |

18.18 |

| NGO worker |

10 |

5.05 |

| Others |

61 |

30.80 |

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents in the study area.

Concerning the preparation of traditional medicine, the local people employed various methods of preparation of traditional medicines for different types of ailments. The most principal method of TMP preparation reported was in the form of crushing (20%) and the least was cooking (1.6%) (Table 2). This might be the effective extraction of the plant gives immediate response for health problems when crushed or pounded to increase its curative potential. The result is consistent with the findings of Getnet Chekole, et al. [10] in which crushing is highly reported method of remedy preparation. But it disagrees with the report of Jarsso Belay [9] which revealed that squeezing is the most used preparation method.

| No |

Respondents |

Male |

Female |

Total |

Percentage (%) |

| 1 |

Farmers |

26 |

7 |

33 |

16.66 |

| 2 |

Merchants |

16 |

9 |

25 |

12.62 |

| 3 |

Religious leaders |

26 |

6 |

32 |

16.16 |

| 4 |

Health care workers |

26 |

10 |

36 |

18.18 |

| 5 |

Traditional plant medicine users |

46 |

8 |

54 |

27.27 |

| 6 |

Traditional plant medicine healers |

14 |

4 |

18 |

9.10 |

| 7 |

Total |

154 |

44 |

198 |

100 |

Table 2 Distribution of informant groups by number.

The most widely used route of administration was oral accounted for (56.67%) followed by dermal (29.63%) (Table 2). This is the reason that oral and dermal routes permit rapid physiological reaction of the prepared medicines with the pathogens and increase its curative power [11]. These results are consistent with findings of various ethnobotanical researches elsewhere in Ethiopia and other countries such as that of Mirutse Giday, et al. [12].

Ways of applications and dosage of plant remedies

The prepared traditional medicines were applied in a number of ways, among which drinking (37.57%), creaming (16.76%), and eating (10.40%) were mentioned frequently (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with the finding of Endalew Amenu [13] in which drinking accounted the largest percentage of remedy.

Figure 3 Application ways of remedies for human and livestock ailment treatment.

The dosage of medicine to be administered is given by estimating age, the physical condition of the patient and the severity of the diseases. Amounts to be administered is also estimated by the use of measurements such as length of a finger (for bark, root and stem length), pinch (for powdered plant material) different measuring materials (e.g. spoon, coffee cup, tea cup and glass cups) and number count (for sap/extract drops, leaves, seeds, fruits, bulbs, rhizomes and flowers). But these measurements are not accurate enough to determine the precise amount. Some of the medicinal preparations are reported to have adverse effects on the patients. Informants reported that Hagenia abyssinica, Phytolacca dodecandra and some others are found to have adverse side effects like stomach pain, vomiting and diarrhea. The informants recommended additives for some of these adverse side effects, such as drinking of milk and barley soup immediately after intake of medicinal plants [14]. This study agreed with study made by Abraha Teklay, et al. [15] in Kilte Awlaelo District, Eastern zone of Tigray region of Ethiopia and Amaro district, southern nations and nationalities of Ethiopia showed no agreement in accurate measurement or unit used among informants.

Conditions of preparation of remedies

The results showed that majority of the remedies were prepared using fresh material (50, 53.76%), while 15 species (16.13%) were used in the dried form and 28 (30.11%) either fresh or dried. Similar studies were also conducted by Tadesse Beyene [16] which showed that using fresh materials for different health problems is more than dry materials or dry or fresh. This could be due to the fact that the fresh materials did not lose their volatile bioactive chemicals like oils, which could deteriorate on drying.

Disease types and related medicinal plants in the study area

In the area a total of 57 ailement types (both human and livestock aliments) were recorded along with the medicinal plants. From these disease types, wound is the most frequently mentioned aliment type and it is claimed to be treated by many number (25 species) of medicinal plants. This is followed by Malaria and stomach ache which are claimed to be treated by 14 and 13 species respectively. While Abortion, back pain, bilharzia, ear defect, goiter, infertility, retained placenta and syphilis are claimed to be treated by only a single medicinal plant spcies.

Paired-wise comparison analysis on six most important TMPs claimed to treat wound was performed. The result showed that Acacia abyssinica is the most usefull and effective plant to treat wound followed by Kalanchoe petitiana while Olea europaea ranked sixth. (Table 3) Preference ranking was also made on other six TMPs which were mentioned to treat malaria (Table 4). The result showed that Vernonia amygdalina is the most preferred species that ranked first followed by Juniperus procera. Eucalyptus globulus is the least preferred species followed by Lepidium sativum (Table 4). All of the species particularly thetop ranked ones by preference and pair wise needs special urgent conservation action and sustainableuses. In this regard the results agree with the findings of Behailu Etana.

| Forms of preparation |

Total |

% of total |

Administration |

Remedy counts |

Percentage(%) |

| Crushing |

25 |

20 |

Oral |

153 |

56.67 |

| Pounding & mixing |

25 |

18.4 |

Dermal |

80 |

29.63 |

| Pounding&powdering |

23 |

17.6 |

Nasal |

19 |

7.04 |

| Squeezing |

21 |

16 |

Optical |

6 |

2.22 |

| Chewing |

18 |

14.4 |

Auricular |

5 |

1.85 |

| Pounding & squeezing |

6 |

4 |

Nasal and oral |

4 |

1.48 |

| Decoction |

5 |

4 |

Neck |

3 |

1.11 |

| Cooking |

2 |

1.6 |

|

|

|

| Total |

125 |

100 |

|

270 |

100 |

Table 3 Mode of preparation and route of administration.

| Species name |

Respondents (1-7) |

Sum |

Rank |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| Acacia abyssinica |

3 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

24 |

1st |

| Kalanchoe petitiana |

4 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

21 |

2nd |

| Asparagus africanus |

5 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

19 |

3rd |

| Euphorbia abyssinica |

2 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

16 |

4th |

| Rumex nervosus |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

13 |

5th |

| Olea europaea |

0 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

12 |

6th |

| Total |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

105 |

|

Table 4 Pared-wise comparison on six more mentioned medicinal plants against wound.

Major human diseases in the study area

In the study area, a total of 44 diseases of humans recorded were treated with a total of 50 plant species, where one species can treat a single disease or a number of diseases. Similarly, one ailment can be treated with a combination of plant species or single plant. For example, wound is treated with 25 species of plants, malaria and stomach-ache with 14 species each; body swelling and evil eye treated with 10 species each, tonsillitis with 9 species. Fibril illness, scabies (itches) and skin rash treated with 7 species each. Most of the reported medicinal plants were used to treat human ailments. This showed that, the people of the study area are more knowledgeable and give great attention about human ailments as compared to livestock diseases. Similar results were recorded by Seyoum Getaneh [17] in Debre Libanos District, North Shewa Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Medicinal plants recorded in this study also used as remedies in other part of the country. For instance, 28 species were mentioned in Mesfin Tadesse [18], 9 species in Debela Hunde [19], 10 species in Abiyot Berhanu [20], 61 species in Endalew Amenu [21], 30 plant species in Fisseha Mesfin [22], and 59 plant species in Seyoum Getaneh [23].

Livestock diseases in the study area

In comparison to human diseases, livestock diseases were treated with a few number of plant species in the study area. A total of 13 livestock ailments were identified that were treated by traditional medicinal plants in the area Common diseases affecting livestock health in the study area were bloating which was treated by 10 species, anthrax and leech by 6 species each, ectoparasite (lice) by 5 species, rabies by 3 species, erythroblasts, horse disease, retained placenta and cocoidiosis are treated by 2 species each and the remaining diseases are treated by 1 species each In addition, proper documentation and understanding of farmer’s knowledge, attitude, and practices about the occurrence, cause, treatments, prevention and control of various ailments is important in designing and implementing successful livestock production (Table 5).

| Species name |

Respondents |

Sum |

Rank |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| Vernonia amygdalina |

6 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

26 |

1st |

| Juniperus procera |

5 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

25 |

2nd |

| Allium sativum |

4 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

24 |

3rd |

| Zingiber officinale |

3 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

23 |

4th |

| Lepidium sativum |

3 |

5 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

20 |

5th |

| Eucalyptus globulus |

2 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

18 |

6th |

Table 5 Preference ranking on six most frequently reported plants claimed to treat malaria.

Threats and conservation of medicinal plants in the study area

Threats to medicinal plants: The causes of threats to medicinal plants in the study area were both natural and anthropogenic factors. The most dominant factors affecting the medicinal plants in the study area was agricultural land expansion (34.34%) followed by charcoal production (16.16%). While, the least serious factor was wild fire (4.04%) and then over flooding (4.54%) (Table 6). Similar problems were also emphasized by Vivero, et al. [24].

| Variable |

Factors |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Threats to conservation of medicinal plants |

Agricultural land expansion |

68 |

34.34 |

| Fire wood |

23 |

11.61 |

| Charcoal |

32 |

16.16 |

| Timber production |

17 |

8.58 |

| Construction wood |

21 |

10.60 |

| Medicinal plant trade |

10 |

5.05 |

| Drought |

10 |

5.05 |

| |

Over flooding |

9 |

4.54 |

| |

Wild fire |

8 |

4.04 |

| Total |

|

198 |

100 |

Table 6 Factors affecting Medicinal plants in the study area.

Moreover, the problems identified so far during the course of this study are almost similar to what other literature sources studied in many parts of the country have already stated. The medicinal plants of Wonch district in general and particular are facing the same problem.

The loss of medicinal plants associated with the missing advantages gained from medicinal plants and indiginous knowledge associated with plants [25]. This is observed in wonch district as collection and search for some medicinal plants like Cordia africana, Ekebergia capensis and Thalictrum rhynchocarpum need longer time distance from their residence. Similar findings were also reported in Ethiopia [13] that showed need for agricultural land and for other uses severely threatened plant species in general and medicinal plants in particular.

Merchants, health care workers and other members of society obtained charcoal and timber from Acacia abyssinica and Cordia africana mature plants were recorded in the area indicating over exploitation. Balick and cox [26] argue that quite simply, mature seed producing tree that are the backbone of the population will die and are not replaced and ultimately the resource base on which culturally values are built will disappear because of over harvesting.

Individual farmers in the area as observed during the study penetrated the forest with their axes daily. Here, the scenario is people need plants for their daily life activity i.e. as source of house hold tools, charcoal, furniture, agricultural implements. Thus, those multi-purpose species are on front line to be affected by these activities.

Conservation of medicinal plants and associated knowledge in the study area

Local people of the area know the importance of conserving the plants in both ex-situ and in-situ conservation methods. For instance, some people have started conserving the plants in fenced/protected pasture land (18.62%); in different worship areas (churches, mosqueds) (21.49%), in their farms (18.62%), field/farm margins and around their home gardens (18.58%) and live fences of the famers (20.20%) (Table 7). Nigussie Amsalu [27] have also reported that different worship areas are conservation sites for remnant vegetation in general and medicinal plants in particular. For instance, medicinal plants like Juniperus procera, Olea europaea subsp.cuspidata and Euphorbia abyssinica are found in church forest and also plants like Hagenia abyssinica, Ocimum urticifolium and Ruta chalepensis are found in the majority of home gardens in the study area, as they need these plants in their daily life as spices, medicine or for other values. Plants such as Acacia abyssinica and Cordia africana are also left as remnants of forest in the agricultural field due to their uses as timber source, for construction and fuel wood. Many medicinal plant species were also reported to be rare. Some of these local names are BOODAA WALEENSSUU (meaning plain land of Erythrina brucei), BARAA CALALQAA (meaning valley of Apodytes dimidiate), KARREE BAROODDOO (meaning hilly slope of Myrica salicifolia), and GULLUUGURRAA (meaning mountainous slop of Prunus africana). What then ethno botanists have to learn from such evidences should be the point of focus. Such local clues could be good contributors for designing ecosystem/habitat conservation, rehabilitation and resilience of species in their wild state where they are best adapted. These need an urgent attention to conserve such resources in order to optimize their use in the primary health care system. Some studies have shown that most of the medicinal plants used in Ethiopia are harvested from the wild.

| Variables |

Response Option |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Knowledge on the importance of medicinal plant conservation |

Good |

101 |

51.01 |

| Not good |

97 |

48.99 |

| Total Types of conservation |

|

198 |

100 |

| On worship areas |

42 |

21.49 |

| On protected pasture |

36 |

18.62 |

| In their farms |

43 |

21.11 |

| In home gardens |

37 |

18.58 |

| In live fences of the farmers |

40 |

20.20 |

| Total |

|

198 |

100 |

Table 7 Indiginous knowledge of local community towards medicinal plants conservation.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion

A study on medicinal plant indigenous knowledge, attitude and practice in the area revealed that the community use medicinal plants for maintaining their primary health care. From the study it can be said that the different segment of the community in the study area are in different level of knowledge with regard to traditional plant medicine use, i.e. difference in age, sex, work and education level has impact on the knowledge of the use of traditional plant medicine. In addition, from the result of the study it can be concluded that there are considerable number of community members which do have negative attitude towards use of traditional plant medicines specially educated and youngsters are developing negative attitudes. Moreover, the result of the study revealed that, though negative attitude towards traditional plant medicine is believed to be increasing from time to time, still the community is extensively practicing the use of traditional plant medicines. The ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the study area showed that medicinal plants are used by a large member of the population, and it is the most important means of treating some common human and livestock ailments.

Most medicinal plants collected and identified were herbs and all plant parts were used for preparation of remedies. However, the use of medicinal plants for multiple purposes is leading to depletion in an alarming rate. This is worthy because of some of the uses (Agricultural expansion, firewood, construction, forage, charcoal.) are the major destructive.

Threats that erode indigenous knowledge usually comes from secrecy, oral-based knowledge transfer, the unwillingness of young generation to gain the knowledge, unavailability of the species, the influence of modern education and awareness factors are the major ones.

The results of this study also showed that cultivation of plant species in and around home gardens for different purposes have great contribution to the conservation of medicinal plants and the associated knowledge.

Recommendations

Based on the results of the study, the following recommendations are forwarded.

• Integrated conservation and management program on medicinal plants focused on awareness development and active involement of local community, governmental and non gevrmental bodies shall be practiced in the district.

• Young generation needs raising awareness to avoid negative impacts on the medicinal plants and associated knowledge in the area, hence, documentation of the medicinal plants of the area needs to be continued.

• Avoid uprooting of the plant species for medicinal purpose particularly before its flowering, fruiting and/seeding. If possible, it is better to use other parts of the medicinal plants such as leaves instead of root to protect them from the risk of extinction and endangering the species by collecting the roots or barks of the plants.

• Establishing traditional healers associations by providing supports like land, fund and assistances for cultivations of medicinal plants in the district would help to conserve medicinal plants.

• The societies have no good awareness with tradition plant medicine healers. So that all stakeholders should work together to change the situation and to benefit from traditional plant medicine.

• The government should create possible conditions and include to the teaching curricula about traditional plant medicine use

• To change the attitude of the society any concerned body should give trainings, seminaries about traditional plant medicine use.

• The government and other officials should recognize the use of traditional plant medicine and also the healers of traditional plant medicine need any supports from concerned bodies.

• The insights of religious institution and health care institution should be positive and work together with traditional plant medicine.

• The user’s negative attitude should be changed in to positive and the lack of knowledge about traditional plant medicine use also should be changed by giving training to them and through creating awareness. All stakeholders should develop positive attitude for traditional plant medicine healers. The healers of traditional plant medicine should use appropriate measurements to give the medicine for users.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Written ethical clearance was obtained from the research and ethical committee of the department of biology university of Gondar. A formal letter was written to wonchi district health and agricultural office and each kebele administration to conduct the study. Written informed consent was sought and obtained from every participant who decided to take part in the study. They were assured about the confidentiality of their responses.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the author for reasonable request.

Completing interests

The author declares that they have no financial and non-financial competing interests.

Author contributions

GM was involved in the conception, design, analysis, interpretation, report, and manuscript writing.

Acknowledgements

I extend my deepest gratitude to those who participated in the study for their time to provide relevant information. I wish to extend my thanks to data collectors and supervisors. I also indebted to all those who apply their effort in the process of this study. Finally, thankful to university of Gondar for their financial support provided.

40397

References

- WHO (1979) The promotion and development of traditional Medicine. World Health Organization. Technical Report Series 622, WHO, Geneva.

- Jansen PCM (1981) Spices, Condiments and Medicinal plants in Ethiopia, their Taxonomy and Agricultural Significance. Center for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen, Netherlands, pp: 327.

- Debela A, Abebe D, Urga K (1999) An overview of traditional medicine in Ethiopia: Prospective and Development Efforts. In: Tami rat Ejigu (editor), Ethiopia.

- Abebe D (1986) Traditional Medicine in Ethiopia. The attempt being made to promote it for Effective and letter utilization. SINET Ethiop J Sci pp: 61-69.

- Teferi Gedife and Hahn, H. (2003). The use of Medicinal Plants in self-care in rural central Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol 87: 155-161.

- Getachew Addis, Dawit Abebe and Kelbessa Urga (2001). A Survey of Traditional Medicinal Plants in Shirka Ditrict, Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. Pharm J 19: 30-47.

- Lata A, Etana T (2014) Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice on practice on traditional medicine in lag hare dire dawatown, Addis ababa, Ethiopia.

- Masresha G (2014) Diversity, Structure and Regeneration Status of Vegetation in Simien Mountains National Park, Northern Ethiopia: PhD. Dissertation. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Belay J (2016) Ethnobotanical Study of Traditional Medicinal Plants used by Indigenous People of Jigjiga district, Somali Regional State, Ethiopia: MSc.Thesis. Haramaya University, Haramaya.

- Chekole G (2015) Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in the environs of Tara-Gedam and Amba Remnant Forests in Libo Kemkem District. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed.

- Fisseha Mesfin, Sebsebe Demissew and Tilahun Teklehymanot (2009) An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Wonago district, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 5: 28.

- Giday M, Ameni G (2003) An Ethnobotanical Survey on Plants of Veterinary Importance in two Woredas of Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. SINET: Ethiopian J Sci 26: 123-136.

- Amenu E (2007) Use and Management of Medicinal Plants by indigenous People of Ejaji Area (ChelyaWereda) West Shewa, Ethiopia: An Ethnobotanical Approach, M.ScThesis. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Giday M, Ameni G (2003) An Ethnobotanical Survey on Plants of Veterinary Importance in two Woredas of Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. SINET: Ethiopian J Sci 26: 123-136.

- Teklay A, Abera B, Giday M (2013) An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray Region of Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 9: 65.

- Beyene T (2015) Ethno botany of Medicinal Plants in Erob and Gulomahda Districts, Eastern Zone of Tigray Region, Ethiopia: PhD. Dissertation. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Getaneh S (2009) Ethnobotanical study of Medicinal Plants in Debre-Libanos district, North Shewa Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia: M.Sc. Thesis, Addis Abeba University, Ethiopia, pp: 94.

- Tadesse M (1986) Some Medicinal Plants of Central Shewa and South Western Ethiopia. SINET: Ethiop J Sci 9: 143-167.

- Hunde D, Asfaw Z, Kelbessa E (2004) Use and Management of Ethnoveternary Medicinal Plants by Indigenous People in Boosat, Welenchiti area. Ethiop J Biol Sci 3: 113-132.

- Berhanu A, Asfaw Z, Kelbessa E (2006) Ethnobotany of plants used as insecticides, repellents and anti-malarial agents in Jabitehnon District, West Gojjam. Ethiop J Sci 29: 87-92.

- Amenu E (2007) Use and Management of Medicinal Plants by indigenous People of Ejaji Area (ChelyaWereda) West Shewa, Ethiopia: An Ethnobotanical Approach, M.Sc Thesis. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Mesfin F, Demissew S, Teklehymanot T (2009) An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Wonago district, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 5: 28.

- Getaneh S (2009) Ethnobotanical study of Medicinal Plants in Debre-Libanos district, North Shewa Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia: M.Sc. Thesis. Addis Abeba University, Ethiopia, pp: 94.

- Vivero JL, Kelbessa E, Demissew S (2005) The Red List of Endemic Tree &Shrubs of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Published by Fauna and Flora International (FFI), Cambridge, UK.

- Sofowara A (1982) Medicinal plants and traditional medicine in Africa. John Wiley and sons. New york, pp.225-256.

- Balick MJ, Cox PA (1996) Plants, people and culture. Science of Ethnobotany, Newyork, USA.

- Amsalu N (2010) An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants in FartaWoreda, South Gondar Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia: M.Sc Thesis. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.