Keywords

Blue crab; Callinectes sapidus; Yumurtalik Cove; Growth; Natural Mortality

Introduction

Invasive species can dramatically alter the ecosystems they invade (Didham et al. 2005; Lockwood et al. 2007). Invasive species in marine and estuarine ecosystems are particularly common (Grosholz 2002). In such systems, invasive species have been shown to reduce the abundance of native conspecifics (Brenchley and Carlton 1983), induce broad scale changes in marine food webs (Kimbro et al. 2009) and can have negative impacts on directed fisheries (Walton et al. 2002). One common hypothesis explaining the success of invasive species is the enemy release hypothesis (Williamson 1996). Under this hypothesis, the lack of natural enemies allows invasive species to grow at higher rates and experience lower mortality rates compared to either native species, or the invasive species in its native range (Williamson 1996). For example, invasive marine invertebrates are generally larger in their introduced range than in their native range (Grosholz and Ruiz 2003). Even in cases where there is no growth advantage, the lack of natural predators can allow invasive species to exhibit higher survivorship, thereby increasing overall population growth rates of invasive species.

The blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, is endemic to the western Atlantic basin. It is a widely distributed, estuarine-dependent species that ranges from South America, throughout the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, and along the eastern seaboard of North America as far north as New England (Williams 1974). Throughout this range, the blue crab is an important component of estuarine food webs, acting as a dominant, opportunistic benthic predator and scavenger (Hines 2007). In turn blue crab is an important prey for fish, including, striped bass (Morone saxatilis), red drum (Sciaenops ocellatus) and croaker (Micropogonias undulatus). Thus blue crab represents an important link coupling benthic and pelagic food webs (Eggleston et al. 1992, Hines 2007).

In addition to its ecological importance, blue crab supports important commercial and recreational fisheries throughout much of its range. Within the United States, commercial fisheries exist from Texas to New York, with landings dominated by catches from Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Louisiana (Miller et al. 2011). The Chesapeake Bay has supported an abundant blue crab population with an intense fishery, which currently supplies over one-third of all US commercial blue crab landings (Miller et al. 2011).

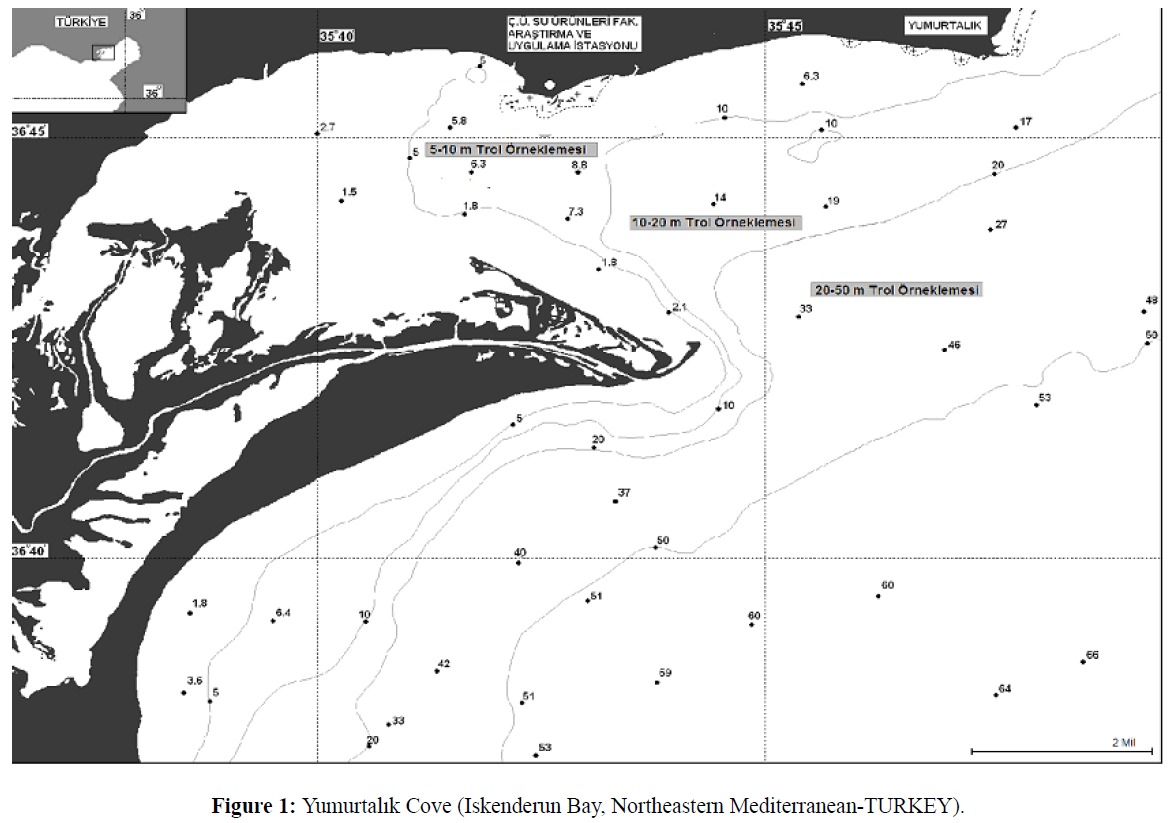

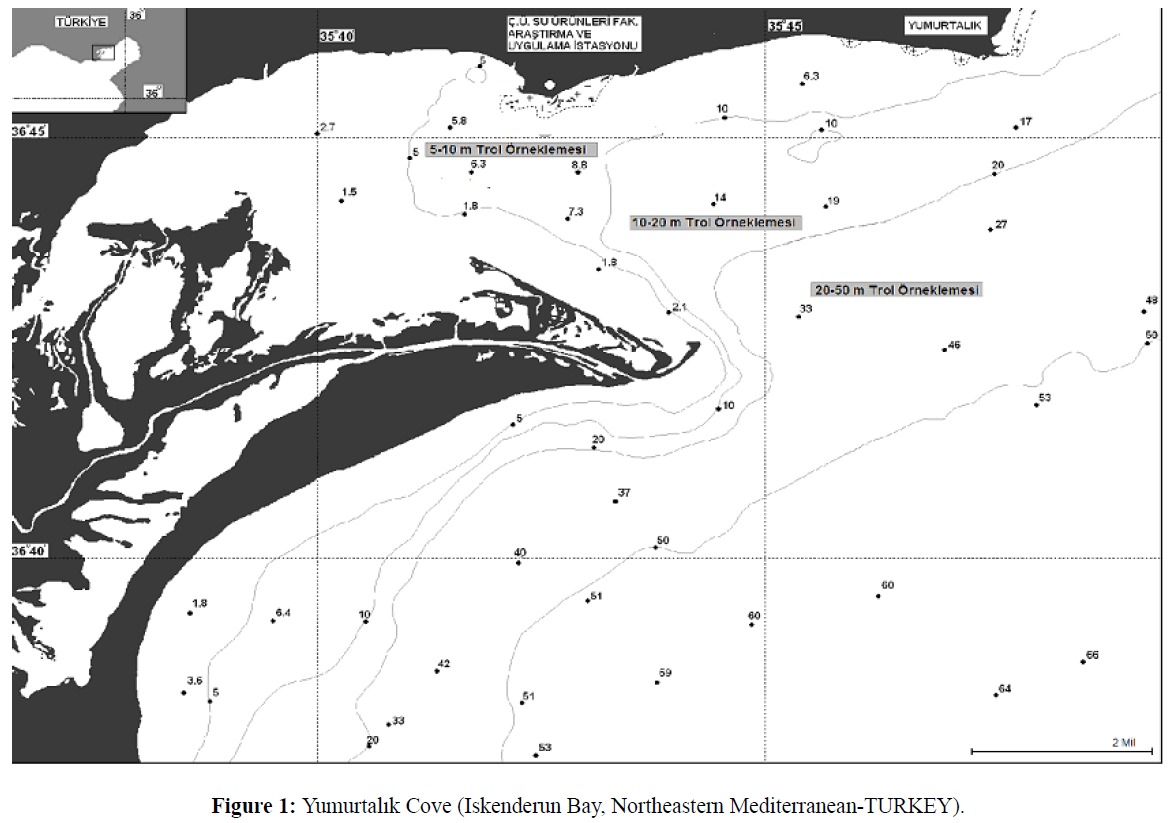

In addition to this endemic range, blue crab has become established as a non-native species in the Mediterranean basin (Holthuis 1961). Holthuis and Gottlieb (1955) suggested that C.sapidus was transported to the Mediterranean in ship’s ballast tanks. The blue crab was first recorded in the Mediterranean in Egyptian waters in the 1940s (Banoub 1963). Subsequently, it has been reported in coastal waters off Italy (Giordani-soika 1951, as Neptunus pelagicus), Israel (Holthuis and Gottlieb 1955), Greece (Kinzelbach 1965), and Turkey (Kocatas and Katagan 1983). Most recently, it has been reported in the Bay of Biscay, along the northwest coast of Spain (Cabal et al. 2006) and The Sacca di Goro lagoon is an area located in the northern part of Italy (Manfrin et al., 2015). The ecology of the blue crab populations in the Mediterranean has been studied most in Turkish waters, where it is distributed from the eastern side of the Mediterranean Sea northwards to the Black sea (Figure 1 Atar et al. 2002). It has been reported in 15 lagoonal systems along the Turkish coast (Enzenross et al. 1997). These populations now support important commercial fisheries. The fisheries expanded quickly in the 1980’s, and the catch reached 77 t in 2009. But catch rapidly decreased 1 t in 2013 (http//tuikrapor.tuik.gov.tr/reports). All of Turkey’s commercial blue crab landings are reported from the eastern Mediterranean.

Figure 1: Yumurtalk Cove (Iskenderun Bay, Northeastern Mediterranean-TURKEY).

Due to its high economic value, the distribution and ecology of the blue crab in Turkish waters is receiving more attention (Gökçe et al. 2006). Determining patterns of growth in blue crab has is important because of central role of growth in understanding a species life history and its susceptibility to exploitation (Miller and Smith 2003). Several important aspects of blue crab growth and mortality have been documented in endemic range (e.g., Brylawski and Miller 2006; Smith and Chang 2007; Hewitt et al. 2007). In contrast, despite the extensive body research of the life history of the blue crab within its endemic range, there is little information on aspects of the life history and population dynamics of blue crab outside of this range. Enzenross et al. (1997) examined the distribution of blue crab in Turkish waters. There are some studies about blue crab in Turkey concerning length-weight relationships (Gokce et al., 2006; Ozcan and Akyurt, 2006; Sangun et al., 2009). Atar and Secer (2003) have published a length-weight relationship for blue crab in Beymelek lagoon. Agbas et al., (2008) reported morphmetric characteristics for blue crab in Köycegiz lagoon. Tureli (1999); Tureli and Erdem (2003); Tureli-Bilen and Yesilyurt (2014); Sumer et al. (2013) reported population biology and growth in Turkey. Here, we report the results of studies on the population dynamics of blue crab in Yumurtalik Cove, part of Iskenderun Bay on the Turkish Mediterranean coast (Figure 1). In particular, we focus on quantifying growth of blue crab to compare observed estimates of growth in Turkish waters to compare to growth estimates of blue crab within its native range. We also provide estimates of mortality rates based on indirect methods using life history invariance relationships (Hewitt et al. 2007).

Material and Methods

Yumurtalik Cove is small (area of 70 km2), shallow (average depth of 5 m, maximum depth of 15 m) embayment of Iskenderun Bay (Figure 1). Iskenderun Bay is a tidal system with a typical tidal range is 0.4-0.6 m (MacPherson et al. 1988). Air and water temperature vary seasonally. Peak summer air and water surface temperature of approximately 30°C occur between August- September. Winter average air and water surface temperatures are approximately 15°C (www.Fao.org/docrep/field/003/S8479E/S8479E07.htm).

The inner part of Yumurtalik Cove is very shallow and there are some small lagoons connected to it by narrow straits. The bottom is principally mud and clay. On the northwestern side of Iskenderun Bay, the bottom slope is modified by sediments from inflowing rivers. Most of the sediments in this region are a mixture of mud and clay with sand in shallow areas (25 to 30 m).

Extensive beds of sea grass (Posidonia sp) occur in the muddy areas. The most important fresh-water supply into Iskenderun Bay is from the Ceyhan River, which discharges within the Yumurtalik Cove.

Blue crabs were sampled monthly in the Yumurtalik Cove between February –December 1997 using a small shrimp trawl (15 m head rope with 14 mm-mesh cod end) towed for 30 minutes at depths of between 5 and 30 m (Figure 1). Each monthly survey sampled crabs at 6 randomly assigned stations. Trawl shots of about 30 were undertaken All crabs collected during the sampling were identified, enumerated and measured for carapace width (nearest mm) using vernier calipers. Subsequently, crab size distributions were binned into 1 cm increments. Monthly length–frequency distributions for use in growth estimation were constructed. The von Bertalanffy growth function was used to estimate growth parameters, using the ELEFAN I routine incorporated in the FISAT software (Gayanilo et al., 1995). The seasonalized von Bertalanffy growth function can be described as:

where L∞ is the asymptotic carapace width to which the crabs grow, K’ = annual growth coefficient (yr–1), t0 = month of spawning, ts = the time of the year when the growth rate is highest; C = the amplitude of the seasonality factor, which ranges between 0 and 1 (i.e. for values of C close to 0 no seasonality occurs, for values close to 1 the amplitude is maximal). The ELEFAN estimates only two of the three growth parameters (L∞ and K), thus we computed the third parameter (t0) by the empirical equation of Pauly (1983) for growth fitting:

Longevity was calculated from tmax≈ 3/K (Pauly, 1980). The growth performance index Φ’ (Pauly and Mumo 1984) was calculated for each set of CL, and K, according to the equation

We indirect approach to estimating mortality rates. Hewitt et al. (2007) used indirect approaches to estimating the rate of natural mortality (M) for blue crab in Chesapeake Bay. Hewitt et al. (2007) summarized the distribution of estimates of M from eight different empirical relationships. Based on the growth relationships developed above, and estimates of the age at maturity provided by Tureli (1999), we used six different empirical relationships to estimate Natural Mortality (M).

Results

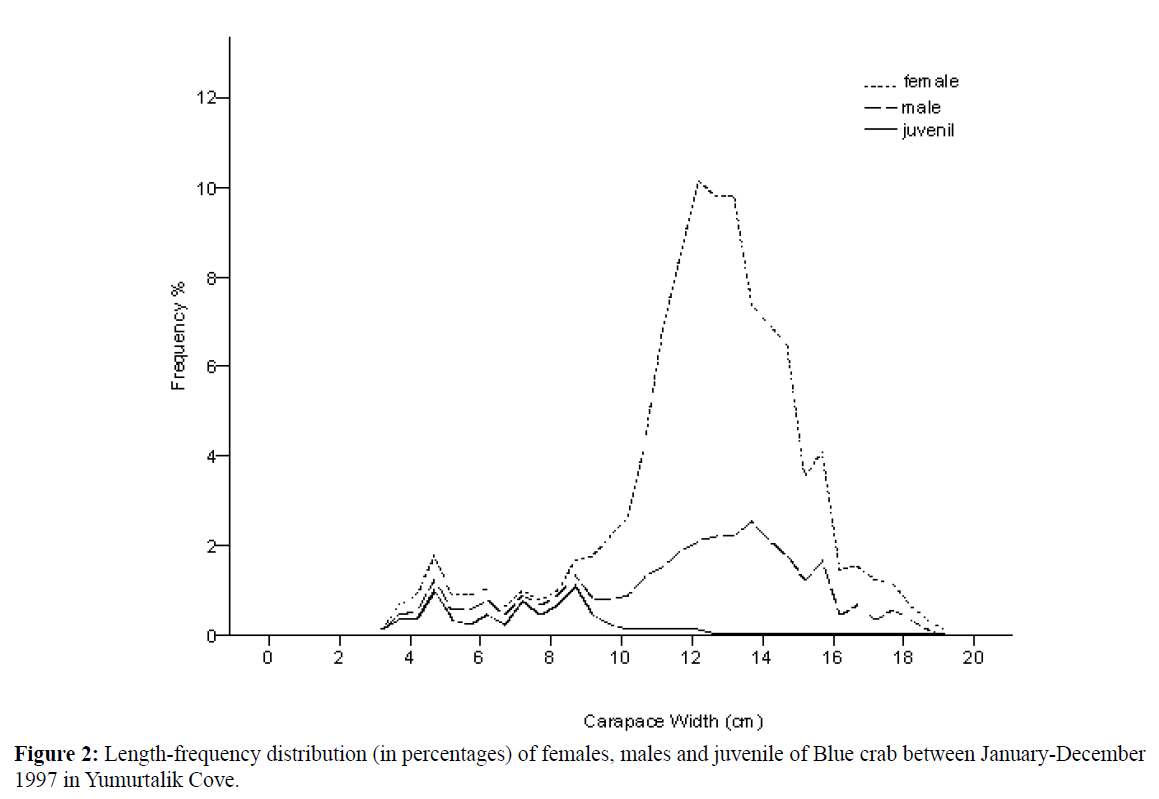

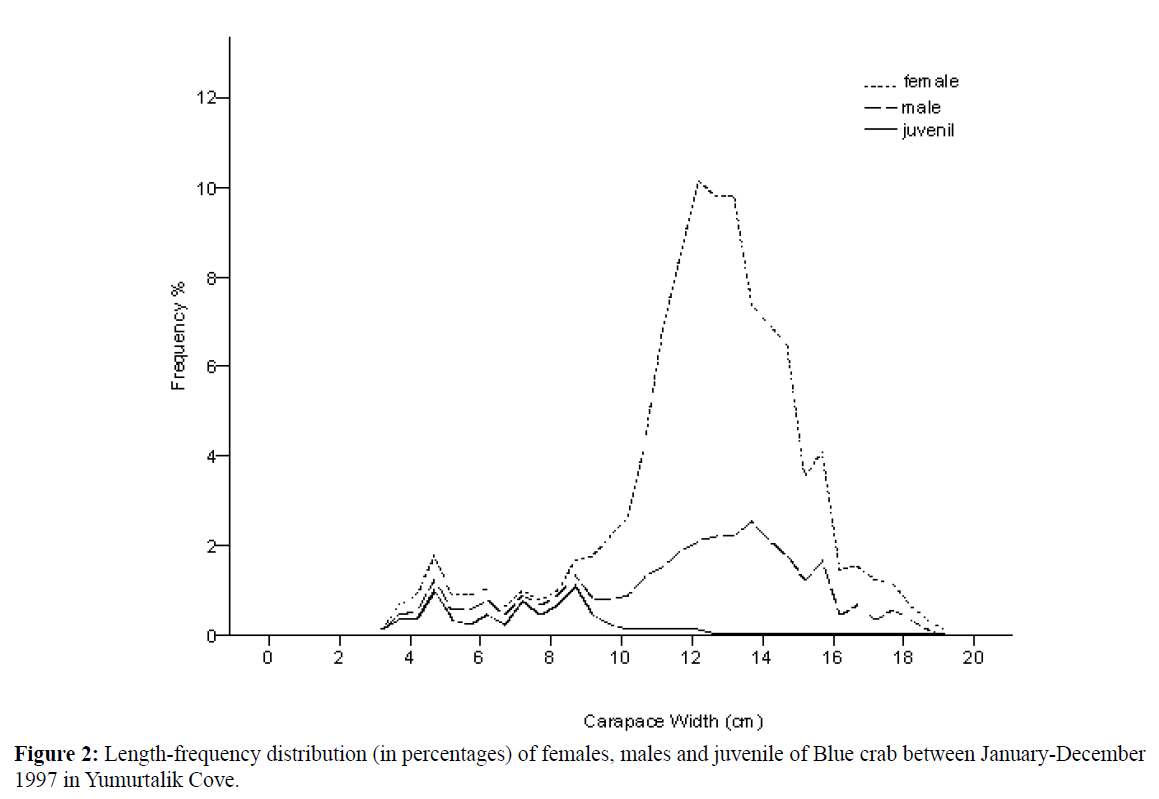

A total of 908 blue crabs, 611 females (427 mature and 184 ovigerous), 234 males and 63 juvenile were sampled January- December 1997 from Yumurtalik Cove. Monthly catch percentages of both sexes were given. Crabs varied from 3.20-19 cm CW with a mean (±SD) of 12.32±2.73 cm CW (Table 1). Dominant length interval was found between 10-16 cm for females, males and 5-9 cm for Juveniles (Figure 2).

| Sex |

|

n |

Mean ± SD |

Minimum |

Maksimum |

| Females |

OF

|

184

|

12.68 ± 2.13

|

4.90

|

19.00

|

| males |

|

234 |

12.82 ± 2.68 |

3.70 |

18.60 |

| Juvenile |

|

63 |

7.01 ± 2.07 |

3.20 |

12.30 |

| Total |

|

908 |

12.32 ± 2.73 |

3.20 |

19.00 |

Table 1: The mean carapace width (cm), range in width for Blue crabs from Yumurtalik Cove sampled from January-December 1997.

Figure 2: Length-frequency distribution (in percentages) of females, males and juvenile of Blue crab between January-December 1997 in Yumurtalik Cove.

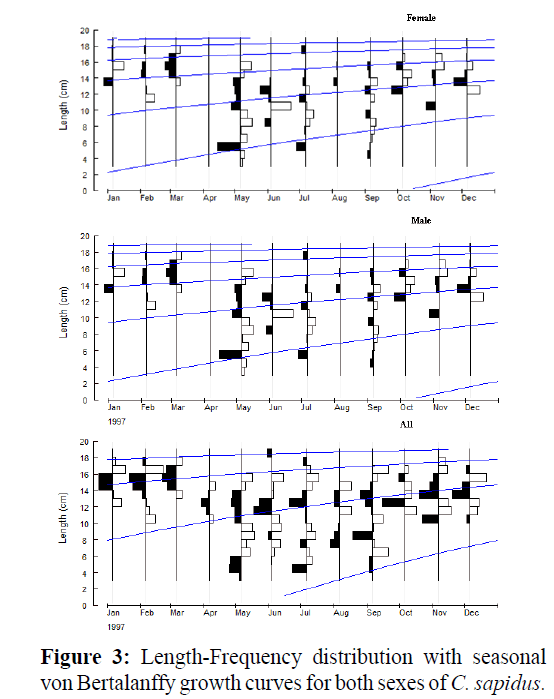

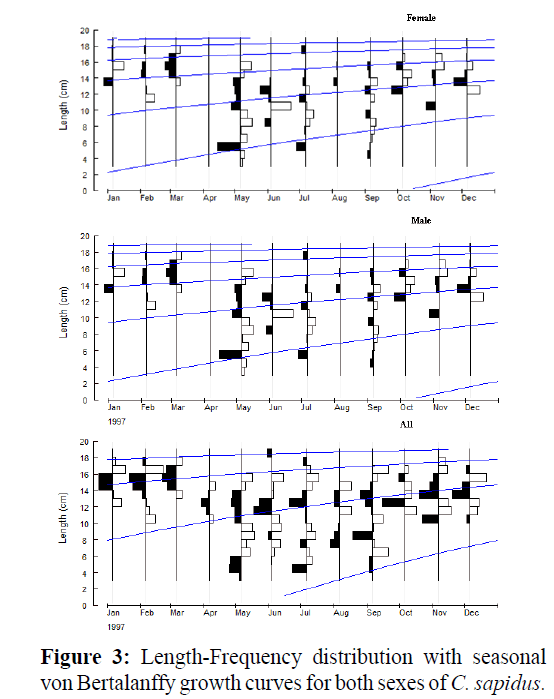

The seasonal von Bertalanffy growth parameters estimated from length-frequency distribution analysis (LFDA) for females and males are shown in Table 2. The LFDA analyses showed that males have higher L∞ (20.95 cm CW) than females (20.66 cm CW), whereas the growth coefficient value, K was higher female (0.74) than males (0.50). Seasonal growth oscillation was not determined for females (C=0), but males exhibit a bit more seasonal growth (C = 0.2). The start of the slowest growth period was estimated in January for males (WP =1). Growth performance indices (Φ´) for females (2.499) were stronger than males (2.315) Potential lifespan was estimated to be 3.7 years for all crabs (Table 2). No winter cessation of growth was apparent (Figure 3).

| Sex |

tmax |

CWα(cm) |

K(year-1) |

t0 |

C |

WP |

Φ’ |

Rn |

| Females |

4 |

20.66 |

0.74 |

-0.24 |

0 |

0 |

2.499 |

0.428 |

| Males |

6 |

20.95 |

0.50 |

-0.36 |

0,2 |

1 |

2.315 |

0.497 |

| Total |

3.7 |

20.16 |

0.81 |

-0.22 |

0 |

0 |

2.517 |

0.322 |

Table 2: Von Bertalanffy growth parameters for both sexes of C. sapidus.

Figure 3: Length-Frequency distribution with seasonal von Bertalanffy growth curves for both sexes of C. sapidus.

Indirect estimates of M, over the full range of plausible input parameters, ranged from 0.53-2.2 (Table 3). The six indirect approaches we used produced largely non-overlapping values. The maximum number of studies with overlapping values was 1-2.0. Therefore, unlike for Hewitt et al. (2007) analysis of indirect approaches to estimating in M for blue crab in Chesapeake Bay, no range of values appears to be clearly supported.

| Method |

Source(s) |

Equation |

Input parameter estimates |

M range |

| 1 |

Charnov and Berrigan (1990), Charnov (1993), Jensen (1996) |

|

tm=1-1.67

|

0.98-2.2 |

| 2 |

Charnov (1993), Jensen (1996) |

M = X2 · k |

X2=1.5-1.65

|

1.21-1.33 |

| 3 |

Pauly (1980) |

log (M)= -0.066-0.279.log( CWα) + 0.6543.log (k) + 0.4634.log (T) |

K=0.81

|

1.30 |

| 4 |

Roff (1984) |

|

Tm=1-1.67

|

0.84-1.94 |

| 5 |

Lorenzen (1996) |

M=3W-0.288 |

W=3.4-407 |

0.53-2.10 |

| 6 |

Alverson and Carney(1975) |

M=3K/(e0.38K.tmax -1) |

Tmax=4-6 |

0.71-1.32 |

Table 3: Indirect estimates of natural mortality for blue crab in the eastern Mediterranean. Parameter values for each model are either taken directly from this study (k, CWα, T), were taken from Tureli (1999), or came from Hewit et al. (2007).

Discussion

We estimated growth parameters and natural mortality for blue crab in the eastern Mediterranean, outside of its endemic range. Our data suggest that blue crab in the eastern Mediterranean do not exhibit a period of winter stasis in growth, but males exhibit a bit more seasonal growth (C = 0.2) (Table 2).

There have been numerous studies of blue crab growth from within its native range; these data are summarized in Table 4. The reported studies include growth estimates derived from laboratory and field enclosures (Ju et al. 2000), those developed from moltprocess models (Smith 1997), as well as from the results of modal analysis of survey data (Rothschild et al. 1988, Helser and Kahn 1999). There does not appear to be an unambiguous latitudinal trend in these data, but if one is present, it is that crabs grow faster and reach smaller asymptotic sizes in warmer conditions (Louisiana). The estimates of growth for blue crab in Turkish waters reported in this study are different to those reported in the crab’s native range. The average for reported estimates of k in the native range is 0.72 ± 0.29 yr-1 (mean ± SD), whereas that for the eastern Mediterranean was only k = 0.81 yr-1. Summer et al., (2013) reported that k for Beymelek Lagoon crabs (female: 1.064; male: 0.86) is much higher than Yumurtalik cove crabs (Table 4). In particular, if one accepts that growth rates are higher under warmer conditions, then our results from the eastern Mediterranean are even more normal. The growth coefficient for pond-reared crabs (1.09) is much higher than previous estimates for Chesapeake Bay (0.51 to 0.64) and nearby Delaware Bay (0.75) crabs (Ju et al. 2001). However, the our estimate of asymptotic maximum size is more in keeping with the range observed in North American studies (Table 4). This study relied on crabs sampled from Yumurtalik Cove that ranged from 3.20-19 cm cw. Several studies in regions have reported similar size ranges to those used in our studies. For example Atar and Secer (2003) sampled crabs ranging from 51-181 mm cw, Similar, crabs in Camlik Lagoon Lake (Yumurtalik, Turkey) ranged from 23 to 178.0 mm (Gokce et al. 2006), Sumer et.al. (2013) sampled crabs ranging from 28.4-212.7 mm cw in Beymelek lagoon lake (Antalya, Turkey). Finally Tureli (1999) reported male crabs ranged in size from 3.7-18.60 cm; female crabs ranged in size from 2.0-18.10 cm for Iskenderun Bay (Turkey). Thus it does not seem likely that the growth estimates obtained reflect insufficient or biased sampling. It seems that the parameters estimated are reflective of growth conditions for blue crab in the eastern Mediterranean.

| Source |

k (yr-1) |

CWα(cm) |

t0 (yr) |

M |

Φ’ |

| Easten Mediterranean of Turkey |

|

|

| This study |

Females 0.74

|

Females 20.66

|

Females -0.24

|

1.30 |

2.49

|

| Southwestern Coast of Turkey |

|

|

| Sumer et al. (2013) |

Female 1.064

|

Females 18.19

|

Females -0.85

|

|

4.52

|

| Delaware Bay |

|

|

| HelserandKahn(1999)Model1 |

0.75 |

23.47 |

-0.1 |

0.80 |

4.74 |

| HelserandKahn(1999)Model2 |

0.62 |

20.06 |

-0.15 |

0.80 |

4.60 |

| HelserandKahn(1999)Model3 |

0.93 |

20.03 |

-0.15 |

0.80 |

4.60 |

| Chesapeake Bay |

|

|

| Rugoloetal.(1997) |

0.587 |

26.25 |

0.115 |

0.375 |

4.83 |

| Rothschildetal. (1988) |

0.51 |

17.8 |

|

|

|

| Juetal.(2001)Labreared |

0.35 |

18.09 |

|

|

4.51 |

| Juetal(2001)Fieldreared |

0.70 |

24.0 |

0.11 |

|

4.76 |

| Smith(1997) |

0.64 |

19.19 |

0.31 |

|

4.56 |

| North Carolina |

|

|

| Eggelston et al 2004 |

0.74 |

23.77 |

0.02 |

0.87 |

|

| Louisiana |

|

|

| Smith (1997) |

1.45 |

17.59 |

0.13 |

|

4.49 |

| Average (not including this study) |

0.72 |

21.05 |

0.17 |

|

|

| SD |

0.29 |

3.08 |

0.008 |

|

|

Table 4: Published von Bertalanffy growth coefficients and natural mortality M for blue crab.

Growth appeared to relatively constant throughout the year. This is consistent with what is known about the role of temperature in the onset of overwinter stasis (Brylawski and Miller 2006; Smith and Chang 2007).

Temperature measurements in Yumurtalik Cove water during this study ranged from 15.2 to 31.5 °C (Türeli 1999). Indeed, data collected by routine monitoring programs in the region indicate that temperature has never dropped below 9°C (MacPherson et al. 1988). This supports our interpretation of the data that growth continues throughout the year. These observations further suggest that the growth parameters we estimated are legitimate.

Our results showed that the growth performance index (Φ) for C. sapidus was lower than other studies (Table 4). Growth performance of coastal marine environments species could be lower than compared to lagoon species (Sumer et al., 2013).

Determination of the potential longevity (tmax) is perhaps the most contentious current issue in blue crab population dynamics and stocks assessment. The controversy is due to our current inability to directly determine the age of blue crabs (Fogarty and Lipcius, 2007).

The potential longevity (tmax) was estimated at 4-6 yrs for C. sapidus in this study. Existing blue crab population dynamic studies have considered longevities of 3 to 8 years (Fogarty and Lipcius, 2007), Rugolo et al. (1997,1998) and Miller and Houde (1999) investigated estimates of longevity ranging from 4 to 8 yrs for Chesapeake Bay. Kahn and Helser (2005) considered a maximum life span of 3 yrs to be most likely in Delaware Bay. It would appear that the most likely range for blue crab longevity is 3 to 6 yrs depending on location and other factors (Fogarty and Lipcius, 2007).

Given limited direct information about M, we used various indirect methods predict to probable ranges of M for blue crab (Table 4). Each method yields estimates of M based on life history characteristics, such as growth parameters, lifespan, and age at maturity. These empirical methods are often subject to large errors in predictions. In addition, a notable problem with all of methods employed here is that the relationships were developed primarily for fish (Miller et al., 2005). The weight of evidence from empirical and life history analysis indicated that M=1.30 for Yumurtalik cove blue crab population (Table 4). M was estimated Chesapeake Bay blue crab stock 0.9 (Miller et al., 2005), 0.37-0.75 (Miller and Houde 1999).

In conclusion, the results of this study show that The Yumurtalik population produces a large number of young and likely attainments of maturity at a relatively young age. We think that the high total mortality is occurred lack of fishing pressure on Blue crab population in Yumurtalik bay, and the large number of recruits and their high and density-dependent mortality. Further research must to be conducted to determine the full dynamics of blue crab on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey.

9005

References

- Agbas, E., Erdem, Ü., Atasoy,G., TüreliC.andÖ. Duysak (2008). "Köycegiz Lagün Sisteminde Bulunan Mavi Yengeç (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896)'in Bazi Morfometrik Özellikleri ile Et Kompozisyonu", Anadolu Üniversitesi Bilim ve Teknoloji Dergisi, 9 , 65-71

- nAtar, H., Ölmez, M., S. Bekcan and S. Seçer(2002). Comparison of three different traps for catching blue crab (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun 1896) in Beymelek Lagoon. Turk J.Vet. Anim. Sci, 26, 1145-1150

- nAtar, H and S. Secer(2003). Width length-weight relationships ofthebluecrab(Callinectessapidus, Rathbun, 1986) population living in Beymelek lagoon lake. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci., 27,443-447

- nBanoub, M.W (1963). Survey of the Blue crab Callinectes sapidus (Rath.) in Lake Edku in1960.Hydrobiology depertmant,Alexandria Institute of Hydrobiology. Notes and Memories 69, 1-18

- nBrenchley, G.A. and CarltonJ.T.(1983). Competitive displacement of native mud snails by introduced periwinkles in the New England intertidal zone. Biol. Bull. 165, 543–558

- nBrylawski, B.J. and MillerT.J. (2006). Temperature-dependent growth of the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus): a molt process approach. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences,63, 1298-1308

- nCabal, J., Pis MillanJ.A. and ArronteJ.C (2006). A new record of Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea:Decapoda:Brachyura) from the Cantabrian sea, Bay of Biscay, Spain. Aquatic Invasion,1,186-187

- nDidham, R. K., TylianakisJ. M., HutchinsonM. A., EwersR. M, and GemmellN. J (2005).Are invasive species the drivers of ecological change.Trends in Ecology and Evolution,20, 470-474

- nEggleston, D. B., LipciusR. N. and Hines A. H(1992). Density-Dependent Predation by Blue Crabs Upon Infaunal Clam Species with Contrasting Distribution and Abundance Patterns. Marine Ecology-Progress Series,85, 55-68

- nEnzenross, V.L.,Enzenross,R.andBingel,F(1997). Occurrence of Blue crab, Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun 1896) on the Turkish mediterranean and adjacent coast and its size distribution in the bay of Iskenderun. Turk.J.Zool, 21,113-122

- nFogarty, M. J., and LipciusR. N(2007). Population dynamics and fisheries. Pages 711–755inV. S. Kennedy and L. E.Cronin, editors. The blue crab Callinectes sapidus.University of Maryland Sea Grant College, College Park

- nGayanilo, F.C., SparreP. and PaulyD(1995). FAO-ICLARM stock assessment tools (FISAT) user’s manual. FAO Computerized Information Series (Fisheries),8, 126 pp

- nGrosholz, E(2002). Ecologicaland evolutionary consequences of coastal invasions. Ecology & Evolution, 17, 22-27

- nGrozholz, E. D. and Ruiz,G. M (2003).Biological invations drive size increases in marineand estuarine invertebrates.Ecology Letters,6, 700-705

- nGokce, G., Erguden, D., Sangun, L., CekicM. and Alagoz,S(2006). Width/length-weight and relationships of the bluecrab(CallinectessapidusRathbun,1986) populationlivinginCamlikLagoonLake (Yumurtalik). Pakistan J. Biol. Sci., 9, 1460-1464

- nHelser, T.E. and KahnD.M(1999). Stock assessment of Delaware Bay blue crabCallinectes sapidus for 1999. Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Delaware division of fish and Wildlife. Dover, Delaware

- nHewitt,D.,Lambert, D.M.,Hoenig,J.M., Lipcius R. N.,BunnellD.B. et al. (2007).Direct and Indirect Estimates of Natural Mortality for Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society,136,1030–1040

- nHines, A. H (2007). Ecology of juvenile and adult blue crabs. Pages 565-654 in V. S. Kennedy and L. E. Cronin, editors. The Blue Crab Callinectes sapidus. Maryland Sea GrantCollege, College Park, MD

- nHolthuis, L.B. and Gottlieb,E (1955). The occurrence of the American Blue Crab, Callinectes sapidus Rath. In Isreal waters. Bulletin of the Research Council of Israel,5B,155-156

- nHolthuis, L.B(1961). Report on a Collection Crustacea decapoda and Stomatopoda from Turkey and Balkans. Zool. Verhan,47,1-67

- nKahn, D. M., and HelserT. E(2005). Abundance, dynamics and mortality rates of the Delaware Bay stock of blue crabs,Callinectes sapidus. Journal of Shellfish Research,24, 269–284

- nKimbro, D. L., Grosholz, E. D., Baukus, A. J., Nesbitt, N. J., Travis, N. M., et al. (2009).Invasive species cause large-scale loss of native California oyster habitat by disrupting trophic cascades.Oecologia,160,563-575

- nKinzelbach, R(1965). Dieblaue Schwimmkrabbe (Callinectes sapidus), ein Neubürger im Mittelmeer. Natur und museum 95,293-296

- nLockwood, J. L., HoopesM. F. and MarchettiM. P(2007).InvasionEcology. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K.. 304pp

- nMacPherson, N.J., Cittolin, G., CookH. and Besiktepe,S(1988). The farming of sea bass, sea bream and shrimp in Iskenderun Bay, Turkey.An assessment of technical and economic feasibility.Project report S8479/E, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 89 pp

- nManfrin, C.,Turolla, E., Sook ChungJ. and Piero G. Giulianini(2015).First occurrence of Callinectes sapidus(Rathbun, 1896) within the Sacca di Goro (Italy) and surroundings. The Journal of Biodiversity Data,11, 1640

- nMiller,T.J. andHoude,E.D(1999).Blue crab target setting. Final report to the LivingResources Sub- committee of the Chesapeake Bay Program. University of Maryland Centerfor Environmental Science (UMCES) Technical Series No. TS-177-99, Chesapeake Bay Program, U.S. EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), 410 Severn Avenue, Annapolis, MD 21403. 167 pp

- nMiller, T. J. and S.G. Smith (2003). Modeling crab growth and population dynamics: Insights from the Blue crab conference. Bulletin of Marine Science,72,537-541

- nMiller, T. J., MartellS. J. D., BunnellD. B., Davis,G., Fegley,Let al.(2005). Stock assessment of the blue crab in Chesapeake Bay, 2005. University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Technical Report Series TS-487-05, Solomons

- nMiller, T. J., Wilberg M. J., Colton A. R., Davis G. R., Sharov A. F., et al. (2011). Stock assessment of blue crab in Chesapeake Bay.UMCES Technical Report Series TS-614.11.University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Cambridge, MD

- nJu, S-J(2000).Development and application of biochemical approaches for understanding age and growth in Crustacea. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, 139 pp

- nJu, S-J., SecorD.H.and HarveyH.R(2001).Growth rate variability and lipofuscins accumulation rates in the blue crab Callinectes sapidus.Marine Ecology Progress Series,224, 197-205

- nPauly,D.(1984).FishPopulationDynamicsinTropical Water: a manual for use withprogramme calculators. ICLARM Studies and Reviews,8, 325 pp

- nPauly,D.andMunro,J.L(1984).Oncemoreonthe comparisonofgrowthinfishandinvertebrates. Fishbyte,2, 21

- nSmith,S.Gand Chang.C.L (2007). Molting and Growth. In The Blue crab Callinectes sapidus , eds. V.S. Kennedy and L.U. Cronin, 197-245. Maryland Sea Grant Book College Park, Maryland

- nRugolo, L., Knotts, K., Lange A., Crecco V., Terceiro,Met al.(1997). Stock assessment of Chesapeake Bay blue crab (Callinectes sapidus).NOAA, Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee, Annapolis, MD

- nRugolo, L. J., KnottsK. S., LangeA. M. and CreccoV. A (1998). Stockassessment of Chesapeake Bay blue crab (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun). Journal of Shellfish Research,17,493–517.

- nRothschild,B.J.,Stagg,C.M.,Knotts,K.S.,DiNardo,G.T. andChai,A(1988).Bluecrabstockdynamicsin Chesapeake Bay. Final Report submitted to Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee, March 1988

- nSangunL., TureliC., Akamca,Eand Duysak,O (2009). Width/Length-Weight and Width-Length Relationships for 8 Crab Species from the North-Eastern Mediterranean Coast of Turkey, Journal of Animal and Advances, 8, 75-79

- nSmith, S. G(1997).Models of crustacean growth dynamics.Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Maryland, College Park, MD

- nCetin S., Teksam, I.,Karatas.,H. T.,Beyhan and Menderes,C(2013). Growth and Reproduction Biology of the Blue Crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896, in the Beymelek Lagoon (Southwestern Coast of Turkey). Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences,13, 675-684

- nOzcan, T., and Akyurt, I(2006). Population biology of sand crabPortunuspelagicus(Linneaus,1758)andblue crab(CallinectessapidusRathbun,1896)in IskenderunBay.EgeUniv.JFishAquaticSci,23, 407– 411

- nTüreli, C(1999). Aspects of the biology of blue crab (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896) in Iskenderun Bay (Turkey). University of Cukurova, Institute of natural and applied science. Ph.D.Thesis

- nTüreli, C and Erdem,U(2003). "Kuzey Dogu Akdeniz, Iskenderun Körfez’indeki Mavi Yengeç (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896) in Morfometrik ve oransal Büyüme Özellikleri", XII. Ulusal Su ürünleri Sempozyumu, 356-361

- nTureli Bilen, C and Yesilyurt,I. N (2014). “Growth of blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, in the Yumurtalik Cove, Turkey: a molt process approach”, Central European Journal of Biology, 9,49-57

- nWalton, W. C., MackinnonC., RodriguezL. F., ProctorC. and G. A. Ruiz(2002).Effect of an invasive crab upon a marine fishery: green crab, Carcinus maenas, predation upon a venerid clam, Katelysia scalarina, in Tasmania (Australia).Journal of Experimental MarineBiology and Ecology,272,171-189

- nWilliams, A. B(1974).The swimming crabs of the genus Callinectes (Decapoda: Portunidae).Fishery Bulletin,72, 685-798

- nWilliamson, M. H(1996).Biological Invastions.Chapman and Hall, London , UK.