Introduction

|

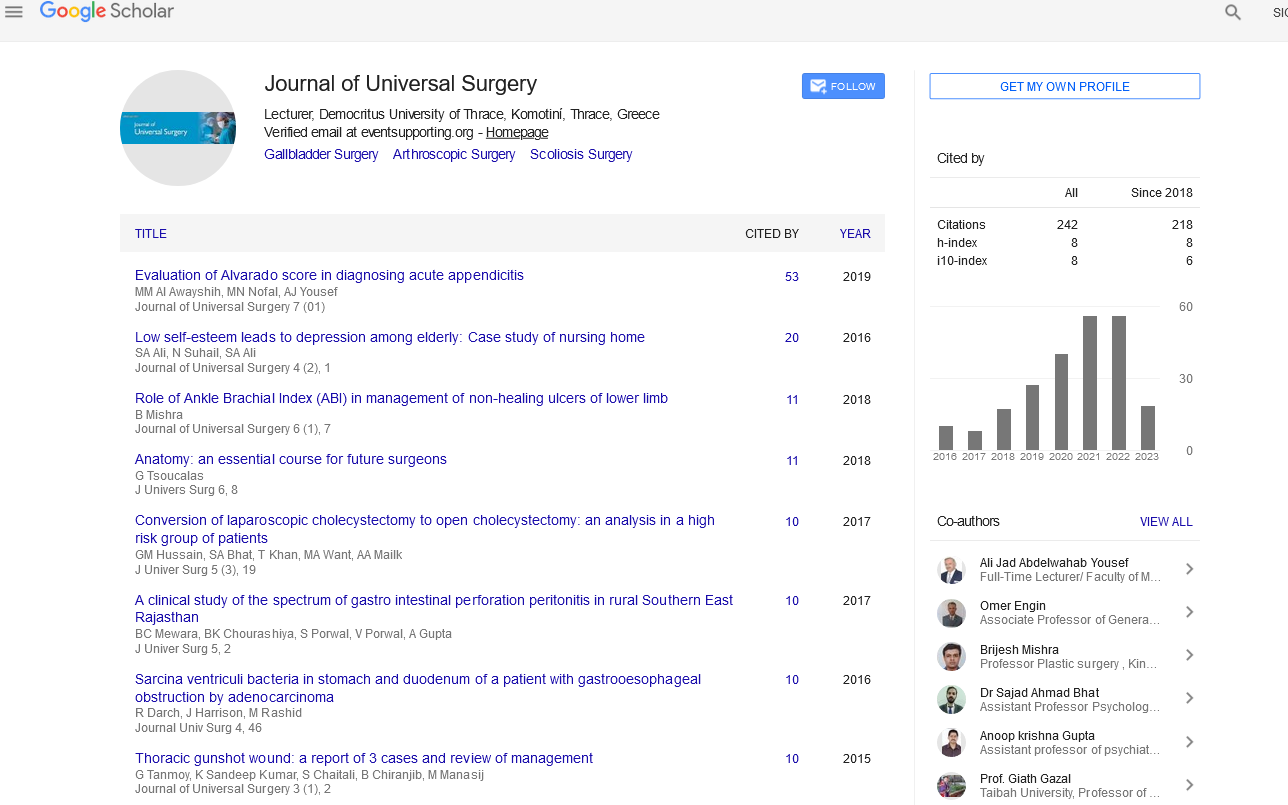

| Osler-Weber-Rendu disease (OWRD) or Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder that causes muco-cutanesous and visceral vascular dysplasia and results in increased tendency for bleeding [1-4]. Patients with HHT may present with variety of symptoms and management differs accordingly. Epistaxis is the most common symptom of HHT and mucocutaneous telangiectasia the most common sign [5]. Here we describe the anesthesia management of a patient presenting with epistaxis in emergency suffering from this syndrome. |

Case Report

|

| A 50 year old male patient of Indian origin came to the emergency with severe epistaxis. Past history and records revealed recurrent epistaxis with definitive positive family history and telangiectasia over nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses. He had been diagnosed previously as HHT due to presence of vascular malformation in the nose and paranasal sinuses by endoscopy and stomach by upper GI endoscopy. After admission his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg, pulse 124/minute, room air SaO2 96%. Investigation revealed Hb 6.5 gm/dl, PCV 16 gm/dl. Chest auscultation revealed no crepitation and bilateral vesicular breath sound was present. He was stabilised with 500 ml hydroxyl-ethyl starch till blood products were made available, followed by 3 unit packed cell and 4 unit FFP transfusion. Patient received tranexamic acid 1 gm slow I.V infusion to control the bleeding, glycopyrrolate to reduce secretions, pantoprazole as antiulcer prophylaxis and Ondansetron to reduce reflux. Along with resuscitation, surgical exploration with control of bleeding under general anesthesia was planned. As blood in stomach was a possibility and patient’s fasting status was unknown, rapid sequence induction was carried out with thiopentone 5 mg/kg and succinylcholine 2 mg/ kg and trachea was intubated with a 8.5 mm I.D. cuffed portex endotracheal tube. A urinary catheter was inserted and orogastric tube aspiration was done. Maintenance of anesthesia was done with sevoflurane, nitrous oxide and oxygen, and atracurium as a muscle relaxant. Several telangectasias were found over the anterior part of the nasal septum which was thoroughly cauterized with diathermy under endoscopic guidance. This was followed by septo-dermoplasty to stop the bleeding. Intraoperatively tranexamic acid was given (1 gm) along with local packing with lignocaine and adrenaline mixture. Intraoperatively controlled hypotension was induced with sevoflurane and propofol boluses to maintain systolic blood pressure between 90 to 100 mmHg. Patient was reversed by using standard reversal techniques with neostigmine and glycopyrollate. Postoperative period was uneventful (Figure 1). |

Discussion

|

| HHT is a rare systemic fibro vascular dysplasia [6] with incidence varying from 1 in 5,000 to 10,000 [7] to 1 to 2 in 1,00,000 [6]. Sutton [8] in 1864 first described this syndrome in a man with a vascular malformation and recurrent epistaxis. In 1896 Rendu [9] first noted the association between hereditary epistaxis and telangiectasia in a 52 years old man. Osler [10] in 1901 and Weber [11] in 1907 further elaborated the association between hemorrhagic lesions in skin and mucous membranes and its familial inheritance. Although the disease is popularly known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, the name ‘hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia’ suggested by Hanes [12] in 1909, recognizes the characteristics that define the disease. |

| HHT is manifested by mucocutaneous telangiectases and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in different parts of body. Lesions can affect the nasopharynx, central nervous system (CNS), lung, liver, and spleen, as well as the urinary tract, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, conjunctiva, trunk, arms, and fingers [2,13]. Impaired signalling of transforming growth factor-ß/bone morphogenesis protein (TGF-β/BMP) [14-17] as well as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [18,19] has been attributed as the primary cause of HHT. The gene mutations found to be responsible are as mentioned in Table 1. |

| “definite” if 3 or more criteria are present, “possible or suspected” if 2 criteria are present, and “unlikely” if 0 or 1 criterion is present. |

| The diagnosis of HHT is made clinically on the basis of the Curaçao criteria [3], established in June 1999 by the Scientific Advisory Board of the HHT Foundation International, Inc. The 4 clinical diagnostic criteria are as follows: |

| HHT Foundation International - Guidelines Working Group [20] has recommended diagnosis of HHT using the Curaçao Criteria (Table 2) or by identification of a causative mutation. |

| Histopathology of HHT lesions show many layers of smooth muscle cells without elastic fibers and very frequently arterioles directly communicating with smooth muscle cells. As a result telangiectases are very sensitive to slight trauma and friction. HHT may present in children as bleeding but usual age of presentation in adulthood [4]. Male and females are equally affected [21]. Classic triad of presentation include telangiectases of the skin and mucous membranes, epistaxis, and a positive family history. Epistaxis may be present in upto 95% cases [4,22] whereas skin lesions account for 75-90% of presentations [22,23]. Skin telangiectasias rarely cause bleeding [4]. Gastrointestinal telangiectasia may occur in 10-33% patients [24] most commonly in the stomach and upper duodenum [24]. Significant bleeding from gastrointestinal tract may occur in 25% patients older than 60 years and may increase with age [25]. Pulmonary involvement in the form of arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) may be present in 75% HHT1 and 44% HHT2 patients [26]. Patients with pulmonary involvement are at high risk of developing cerebral thrombotic and embolic events including stroke, brain abscess, or transient ischemic attacks due to right-to-left shunting [14,24]. Cerebral AVMs may be present 15-20% HHT1 and 1-2% HHT2 patients [26-30], and may present with seizure, headache or intracranial haemorrhages [4,31]. Hepatic AVMs may be present upto 74% cases [32] but usually asymptomatic [4]. Management strategies for AVMs associated with HHT may differ with location and presentation and depicted in Table 3. |

| Patients with HHT presenting with continuous bleeding pose a serious problem to the anaesthesiologists. Pre-existing anemia due to recurrent bleeding is common and sudden decompensation may lead to heart failure. Uncontrolled bleeding may occur from skin lesions during patient positioning and transport. Epistaxis may lead to aspiration of blood into trachea causing pulmonary edema. Intravenous access may be difficult. Sudden change in blood pressure may cause bleeding from AVMs anywhere in the body, most serious of which is from cerebral AVM. Gastric distension may occur from ingested blood and may cause reflux and aspiration during induction. Any instrumentation including laryngoscopy and intubation, nasogastric tube insertion, urinary catheterisation should be carried out with utmost caution as bleeding may occur from undetected lesions (Figure 2). |

| In stable patients, posted for elective surgery, preoperative optimization with oral or parenteral iron and if necessary erythropoiesis-stimulating agent [33] should be considered. Preoperatively angiogenesis inhibitor or hormone therapy should be considered in selected patients to reduce perioperative bleeding. Careful history and physical examination may indicate any systemic involvement and standard radiological imaging with angiography may be performed to search for hemangiomas in brain, lung, gastrointestinal tract, nose and paranasal sinuses. In unstable patient presenting with severe bleeding focus should be directed to simultaneous resuscitation and hemostasis. Blood transfusion forms the mainstay of volume resuscitation in severely volume depleted patient. Epistaxis should be controlled with tight nasal packing immediately followed by cauterisation of bleeding vessels and dermoplasty if required. Since bleeding does not result from a defect in coagulation cascade, but from the malformed vascular structures, platelet or plasma transfusions are of no use and reserved only to supplement the loss. Antifibrinolytics including tranexamic acid [34,35] and aminocaproic acid [36] have been used with success to control epistaxis. In addition to antifibrinolytic effects, tranexamic acid also stimulates the expression of ALK-1 and endoglin, as well as the activity of the ALK-1/endoglin pathway [37-45]. Intraoperatively controlled hypotension should be used to reduce bleeding. |

Conclusion

|

| Patients with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease (OWRD) or Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) may present with uncontrolled bleeding. Resuscitation alongwith hemostasis forms the cornerstone of treatment. As the bleeding occurs from malformed vessels standard coagulation tests will reveal no abnormality. Management include blood transfusion, antifibrinolytics and surgical hemostasis. Anesthesia strategy should include rapid sequence induction and controlled hypotension. |

Tables at a glance

|

|

|

Figures at a glance

|

|

|

| Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

|