Samir Parekh, Zachary Spiritos, Paul Reynolds, Samir Parekh*, Adam Perricone and Brian Quigley

1Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

2Department of Medicine, Division of Digestive Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

3Department of Pathology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta GA, USA

Corresponding Author:

Parekh S

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

Tel: 404-778-3986

Fax: 404-778-2925

E-mail: smparek@emory.edu

Received Date: January 15, 2017; Accepted Date: February 15, 2017; Published Date: February 21, 2017

Citation: Parekh S, Spiritos Z, Reynolds P, et al. HIV and Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Case Series and Literature Review. J Biomedical Sci. 2017, 6:2. doi:10.4172/2254-609X.100057

Copyright: © 2017 Parekh S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Keywords

HIV; Autoimmune hepatitis; liver biopsy

Introduction

Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH) is a rare disease that is caused by circulating antibodies that cause inflammation and hepatocellular injury. Diagnosis is made through abnormal liver enzymes, detection of circulating autoantibodies, liver biopsy, and the exclusion of other causes of hepatotoxicity including infections and drug-induced liver damage [1]. The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group developed the original diagnostic criteria in 1999 which incorporated liver histopathology, serum studies, viral markers, and other etiological factors into a scoring system. A more simplified scoring system was created 2008 which focuses on liver histology and serum autoantibody which is shown is Table 1 [2].

| Points |

| Autoantibodies |

ANA, SMA, OR LKM>1: 40 |

1 |

ANA, SMA, OR LKM>1: 80

SLA/LP positive (>20units) |

2 |

| IgG |

Upper limit of normal |

1 |

| >1.10 x the upper limit of normal |

2 |

| Liver Histology |

Compatible with AIH

Chronic hepatitis with lymphocytic infiltrations without features considered typical |

1 |

Typical for AIH

Interface hepatitis; lymphocytic/lymphoplasmocytic infiltrates in the portal tracts

Emperipolesis: active penetrations by one cell into and through larger cell

Hepatic rosette formation |

2 |

| Absence of viral hepatitis |

No |

0 |

| Yes |

2 |

| Points |

Points>6: Probable AIH

Points>7: Definite AIH |

|

Table 1: Simplified diagnostic criteria (2008) of the international autoimmune hepatitis group [2].

AIH is considered an autoimmune disorder and hepatic injury is due to a sensitized but reactive immune system. There have been a growing number of cases that describe the co-existence of HIV and AIH. The association between autoimmune disorders and HIV is well described, although not completely understood. The most well studied autoimmune disorders in HIV-infected patients include Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP), vasculitis, polymyositis, dermatomyositis, Graves disease, and primary biliary cirrhosis [3].

Many of these autoimmune diseases are treated based on their underlying cause. For example, polymyositis, psoriasis, and Diffuse Infiltrative Lymphocytosis Syndrome (DILS) are due to proliferation of CD8 T-cells which can occur during the early stages of HIV-induced immunosuppression [4]. The treatment for these autoimmune disorders is antiretroviral therapy; however other autoimmune disorders in HIV patients, such as SLE and Grave’s disease, require treatment with immunomodulators or glucocorticoids.

Case Patient #1

A 21-year-old male with a past medical history of Grave’s disease presented to a hospital with a 3-week history of jaundice and fatigue. He also reported subjective dark urine, anorexia, and lethargy over this time period. On exam he had bitemporal wasting, icteric sclera, a tender abdomen, and asterixis without evidence of encephalopathy. He was not on any medications but endorsed routine intravenous drug use.

Initial laboratory values were significant for transaminitis with AST/ALT of 2499/2088 U/L, INR 1.82 and a total bilirubin of 24.3 mg/dL. An abdominal ultrasound showed mild hepatomegaly. He was diagnosed at that time with HIV, and he had a CD4 count of 753 cell/mL with viral load of 7900 copies/mL. There was concern for autoimmune or viral hepatitis and follow-up serologies were significant for an IgG level of 2060 cells/mL. ANA, ASMA, and a hepatitis panel were negative. An anti-LKM1 was not checked.

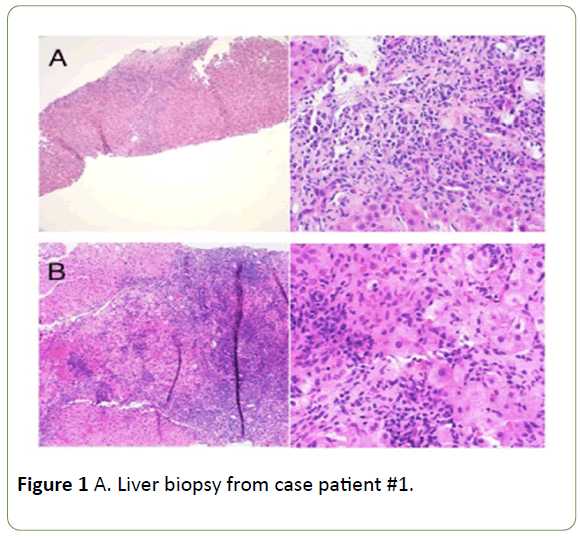

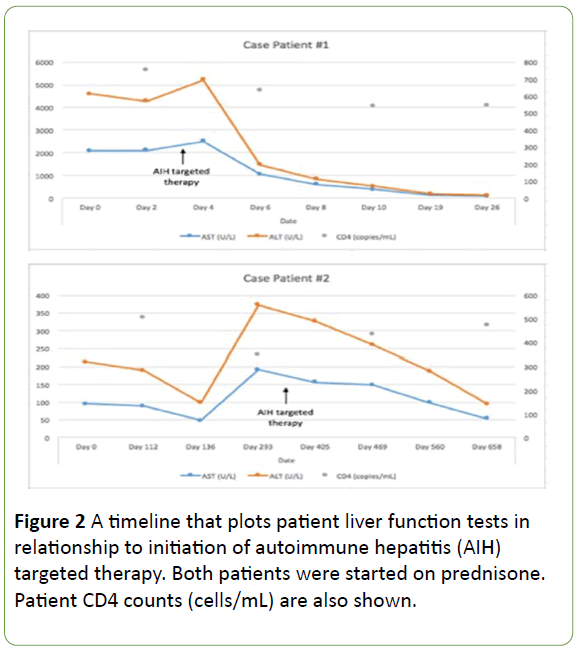

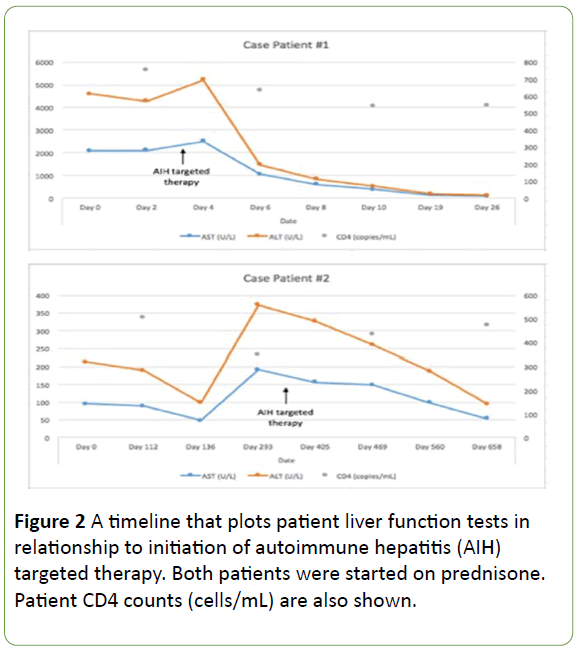

The medical team pursued a liver biopsy which showed interface hepatitis with lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate compatible with AIH (Figure 1). By the simplified diagnostic criteria for AIH he had a probable diagnosis of AIH. After the biopsy, he was started on prednisone 60 mg daily. He was transitioned to prednisone 40 mg daily as an outpatient and simultaneously started on emtricitabine, tenofovir, elvitegravir and cobicistat (Stribild). One month after starting prednisone therapy his transaminases normalized and one month later his bilirubin and INR normalized. His gastroenterologist wanted to transition him to 6-mercaptopurine; however, he was lost to follow up due to incarceration.

Figure 1: A. Liver biopsy from case patient #1.

After 3-months he was released from prison and at that point he saw his outpatient infectious disease physician who noted that he had been off all medications for the past 3-months. Laboratory tests revealed that he re-developed transaminitis (AST 82, ALT 32) without disruption in hepatic synthetic dysfunction. He was re-started on HAART therapy but never followed-up with either infectious disease or gastroenterology.

Case Patient #2

A 59-year-old African-American female with HIV, not on antiretroviral therapy, presented to her outpatient infectious disease physician complaining of parotid gland enlargement and a dry mouth. Her CD4 count on presentation was 137 cells/mL. She tested positive for anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and there was concern for AIDS associated DILS. She was started on efavirenz, emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Atripla).

Four months later she developed polyarthritis involving her bilateral hands, right hip, right ankle, and right knee. She had a positive ANA screen, positive anti-smooth muscle antibody titer 1:80, and a mild transaminitis. She was diagnosed with lupus and started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily and prednisone 5 mg twice a day.

Despite immunosuppressive therapy and an increased CD4 count to 504 cells/mL, she developed significant fatigue and weight loss over the next 3 months. Follow-up serology showed worsening transaminitis with an AST/ALT of 215/156 U/L. A viral hepatitis panel was negative. Diagnostic considerations included drug-induced liver disease (DILI) and autoimmune hepatitis. DILI was thought less likely as the transaminitis preceded hydroxychloroquine therapy, however hydroxychloroquine was discontinued anyway.

Liver biopsy showed lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate in the portal tracts and rosette formation typical for AIH (Figures 1 and 2). By the simplified diagnostic criteria for AIH she had a definite diagnosis of AIH. The prednisone dose was increased from 5 mg daily to 10 mg twice daily and her AST/ALT improved to 99/88 U/L two months later. Azathioprine 50 mg daily was added, and her AST/ALT continued to improve to 49/50 U/L. Clinically she reported no further weight loss or fatigue.

Figure 2: A timeline that plots patient liver function tests in relationship to initiation of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) targeted therapy. Both patients were started on prednisone. Patient CD4 counts (cells/mL) are also shown.

Eventually her prednisone was decreased to 5 mg twice a day without recurrence of her disease. She continued azathioprine 50 mg daily and re-started hydroxycholorquine 400 mg daily. The patient is currently doing well with normal liver enzymes and a CD4 count above 500 cells/mL.

On left, fibrous septum containing a dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with prominent interface and lobular activity. 100x; hematoxylin and eosin. On right, dense plasma cell-rich infiltrate and an area of hepatocyte drop-out at the interface. 400x; hematoxylin and eosin. Biopsy is compatible withautoimmune hepatitis.B. Liver biopsy from case patient #2. On left, dense portal lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with prominent interface and lobular activity. 100x; hematoxylin and eosin. On right, lobular lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with hepatocyte rosette formation. 400x; hematoxylin and eosin. Biopsy is typical for autoimmune hepatitis.

Discussion

Liver disease is the most common cause of non-AIDS related morbidity and mortality in HIV patients [1], which is due in part to co-infection with hepatitis B/C and increased use of alcohol in this population [4]. Additionally, certain antiretroviral therapy can have hepatotoxic side effects, which can range from asymptomatic transaminitis to fulminant liver failure [1] Autoimmune hepatitis is an especially difficult diagnosis to make in an HIV-infected patient due to the numerous potential causes of liver injury in these patients [4] As seen in these two patients, histology is critical in distinguishing AIH from other pathologies.

To date, there have been limited reports in the medical literature of HIV-infected patients with AIH. There is scant data on this patient cohort due to several factors. AIH is a rare disease with a mean incidence of 1-2 per 100,000 persons [1]. Patients with HIV not on anti-retroviral therapy who develop AIDS will not be able to mount the immune response to develop an autoimmune process. Additionally, HIV patients have other, more common reasons to develop liver injury such as medication toxicity, alcoholic hepatitis, viral hepatitis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or AIDS cholangiopathy. Therefore a thorough and proper work-up with a liver biopsy may not be performed because the diagnosis is not considered or the patient expires before diagnostic testing is finished.

The demographic information, HIV-status, and response to immunotherapy of the data on these patients is described in Table 2. In the cases reported, there is a predominance of women who have been found to develop AIH [5-8]. The diagnosis of AIH in HIV positive individuals was made at an average age or 45 years old, with a range of 21-59. Seven of the nine patients presented with asymptomatic elevation in their liver function tests. No patient had a clinical or serologic improvement in their transaminases with antiretroviral therapy alone. Two patients died from opportunistic diseases. Patients with low or undetectable viral loads all had favorable outcomes. There were four patients with detectable viral loads at time of treatment for AIH; two improved with therapy while the other two died of AIDS-related illness. The two patients that died had markedly higher viral loads with a mean of 151,025 copies/mL than those patients that survived who had a mean viral load of 21,776 copies/mL.

| Age |

Gender |

Presentation |

Clinical Response to HAART? |

Treatment |

Outcome |

CD4/VL* at time of AIH treatment |

| 29 |

Male |

Elevated LFT’s |

No |

None |

LFT’s improved |

174/27732 |

| 45 |

Female |

Elevated LFT’s |

No |

Prednisone, Azathiprine |

LFT’s improved |

297/undetectable |

| 65 |

Female |

Elevated LFT’s |

No |

Prednisone, Mycophenolic acid |

LFT’s improved |

922/undetectable |

| 44 |

Female |

Elevated LFT’s |

No |

Prednisone, Azathiprine |

LFT’s improved |

526/undetectable |

| 49 |

Male |

Elevated LFT’s |

No |

Prednisone, Azathiprine |

LFT’s improved, expired due to opportunistic diseases |

285/69,318 |

| 56 |

Female |

Elevated LFT’s |

No |

Prednisone, Mercaptopurine |

Developed Burkitt’s lymphoma and expired |

331/232, 732 |

| 42 |

Female |

RUQ pain, night sweats |

No |

Prednisone |

LFT’s improved |

232/undetectable |

| 21 |

Male |

Lethargy, dark urine |

No |

Prednisone |

LFT’s improved |

753/7900 |

| 59 |

Female |

Elevated LFT’s |

No |

Prednisone, Azathiprine |

LFT’s improved |

483/undetectable |

Table 2: A review of the existing literature on patients with HIV who developed AIH. CD count is in cells/microliter and viral load is in copies/microliter. *Viral load.

Diseases such as DILS, cryoglobulinemia, and psoriasis in HIVinfected patients have a clear relationship with HIV that responds well to antiretroviral therapy [5,9] However other autoimmune diseases where the relationship to HIV is not well understood, may not respond as predictably. Based on these cases and the published literature, it seems that AIH and HIV are mutually exclusive diseases.

That being said, it is unclear whether initiation of HAART therapy can unmask a preexisting AIH. Other autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis have been known to paradoxically worsen after immune reconstitution as part of an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [10]. A diagnosis of IRIS requires worsening of a pre-existing or unrecognized condition during immunologic recovery. There should be a cause-and-effect relationship between initiation of HAART and manifestation of disease [11]. One prospective study found that patients with low pre-treatment CD4 counts (less than 100 cells/mL) developed IRIS typically within 22 to 99 days after initiating HAART [11,12]. The second case patient developed transaminitis 4 months after she started Atripla when her CD4 count was greater than 250 cells/mL. Her pre-treatment CD4 nadir was 137 cells/mL.

Classifying AIH as an IRIS-related illness has prognostic and therapeutic implications. The use of prednisone in HIV patients with suspected IRIS puts them at risk for proliferation of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). In vitro studies suggest that AIDS-KS cells have high levels of glucocorticoid receptor proteins. Retrospective analysis has confirmed steroid use as a risk factor for KS associated mortality [13,14]. Therefore, physicians should use caution when treating patients for AIH-associated IRIS with prednisone who have a history of HIV-associated Kaposi’ sarcoma.

Whether or not AIH-associated IRIS is a discrete entity, patients with HIV who develop AIH should be treated with prednisone rather than HAART monotherapy. However, based on the limited literature available, it is possible that above a certain viral load threshold glucocorticoid treatment leads to a higher mortality risk. The only poor prognostic factor identified to date has been an elevated viral load. Therefore, practitioners should use caution when treating AIH in patients that do not have virologic response to antiretroviral therapy.

In conclusion, AIH in patients with HIV is a rare but increasingly recognized entity which requires careful clinical decision-making in both its diagnosis and treatment. AIH should be in the differential diagnosis when evaluating a patient with elevated liver enzymes, and further case series may help delineate the optimal therapeutic approach in this special population.

18410

References

- Makol A, Watt K, Chowdhary V (2010) Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Review of Current Diagnosis and Treatment. Hepat Res Treat 26: 619-627.

- Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, et al. (2008) Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 48: 169-176.

- Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y (2002) HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev 1: 329-337.

- Rosenbloom MJ, Sullivan EV, Sassoon SA, O’Reillt A, Fama R, et al.(2007) Alcoholism, HIV infection, and their comorbidity: factors affecting self-rated health-related quality of life. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 68: 115-125.

- Puius Y, Dove L, Brust D, Shah D, Lefkowitch JH (2008) Three Cases of Autoimmune Hepatitis in HIV-Infected Patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 42: 425-429.

- O’Leary JG, Zachary K, Misdraji J, Chung RT (2008) De Novo Autoimmune Hepatitis during Immune Reconstitution in an HIV-Infected Patient Receiving Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Clin Infect Dis 46: 12-14.

- Wan DW, Marks K, Yantiss RK, Talal AH (2009) Autoimmune Hepatitis in the HIV-Infected Patient: A Therapeutic Dilemma. AIDS Patient Care STDS 23: 407-413.

- Daas H, Khatib R, Nasser H, Kamran F, Higgins M, et al. (2011) Human immunodeficiency virus infection and autoimmune hepatitis during highly active anti-retroviral treatment: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 5: 133.

- Walker UA, Tyndall A, Daikeler T (2008) Rheumatic conditions in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47:952-959.

- Miranda EJ, Leite OH, Duarte MI (2001) Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with pulmonary sarcoidosis in an HIV-infected patient: an immunohistochemical study. Braz J Infect Dis15: 601-606.

- Grant PM, Komarow L, Andersen J, Sereti I, Pahwa S, et al. (2010) Risk factor analyses for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a randomized study of early vs. deferred ART during an opportunistic infection. PLoS One 5: e11416.

- Murdoch DM, Venter WD, Feldman C, Van Rie A (2008) Incidence and risk factors for the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV patients in South Africa: a prospective study. AIDS 22: 601.

- Fernandez-Sanchez M, Iglesias MC, Ablanedo-Terrazas Y, Ormsby CY, Alvarado-de la Barrera C, et al. (2016) Steroids are a risk factor for Kaposi’s sarcoma-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and mortality in HIV infection. AIDS 30: 909-914.

- Price JC, Thio CL (2010) Liver Disease in the HIV-Infected Individual. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 8: 1002-1012.