Keywords

Youth center; Leisure time; Health promotion; Settings; NGO; Strategies

Introduction

Adolescence as an important life phase

Adolescence is a time that offers many opportunities for good health. It is also when the foundations for future patterns of adult health are established [1,2]. There is a complex web of family, peer, community and cultural influences that all affect the present and future health of adolescents [3]. Since leisure time is a significant part of young people’s lives, and is often spent together with peers, it could be a crucial arena for helping them develop their full potential and attain the best possible health in the transition to adulthood.

Adolescence is a critical development period when risk and protective factors can affect the uptake of health-related behaviors [1,3]. Adolescence is the key period for the adoption of health behaviors relating to for example substance misuse [4]. Improving adolescents’ health requires improving their daily lives in their families, among peers, and in school; and focusing on factors that are protective across various health outcomes [3].

The importance of leisure time for young people

Youth is a time when individuals outside the family become more important to the young, and leisure time can therefore have a greater impact on the beliefs and behavior of adolescents [5]. Leisure-time activities are important for adolescents’ psychological, cognitive and physical development [6]. Because leisure time comprises a large and important portion of young people’s live, arenas where they spend their leisure time, such as youth centers, could be seen as good settings for promoting health. However, leisure-time settings have generally had a minor role in setting-based health-promotion initiatives [7]. In Sweden, two main approaches to organizing leisure-time activities for adolescents can be identified. On the one hand, there is a longstanding tradition of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) running leisure-time activities within, for example, sports. On the other hand municipalities often run youth centers. Little research has been done on youth centers, and especially NGO-run youth centers. Young people with immigrant backgrounds and lower socioeconomic status (SES) participate less in organized leisuretime activities [8-10]. Leisure-time activities gives a broad array of experiences that may not be present in other contexts for young people with lower SES [11]. Participation in leisure-time activities can therefore be of particular significance for adolescents with lower SES, for example a more positive general self-worth and social self-concept [11]. One way to reduce social differences in health is to improve adolescents’ living conditions, for example by enhancing the quality of leisure-time activities [12]. Many studies have also found relationships between different leisuretime activities and academic achievement [13,14].

The organization of youth leisure time

Studies focusing on leisure-time activities use different concepts to describe their organization, for example structure, activity level, or whether they are youth- or adult-driven.

Providing safe, structured, and inclusive settings that focus on a broad range of developmental needs can best serve the needs of young people [15]. Structured activities provide opportunities for skill building and related improvements in specific selfcompetencies, for positive peer interactions and the development of friendship, and for exposure to positive adult role models. Activity settings that require only the passive involvement of adolescents seem unlikely to promote healthy development [15].

Participation in highly structured leisure activities is linked to low levels of antisocial behavior, although participation in lowstructured activities (i.e. youth recreation centers) is connected to high levels of antisocial behavior [16]. The same study also found that participants in low-structured activities were characterized by deviant peer relations and poor relations between parent and children [16].

Leisure studies have often focused on the correlates of different types of activities, such as constructive, organized activities and relaxed leisure activities [15]. However, one study demonstrated that multiple activity settings including both constructive and passive activities reported significant contributions to the prediction of student achievement [17].

A comparison of youth-driven and adult-driven programs for highschool- aged youth in USA showed that the participants in the youth-driven programs experienced a high degree of ownership and empowerment, and reported development of leadership and planning skills. In the adult-driven programs, the adults crafted student-centered learning experiences that facilitated participants’ development of specific talents. In both approaches, young people also gained self-confidence and benefited in other ways from the adults’ experience [18]. Strategies that place the adolescent years at center stage rather than focusing only on specific health agendas provide important opportunities to improve health, both in adolescence and later in life [1].

From previous research, we know that adolescence is important for young people's health development. Leisure-time activities and how they are organized affects young people’s health development. Leisure activities can be used to reduce health inequalities. However, young people with lower socio-economic status participate less in organized leisure-time activities [8- 10]. Since many young people spend their leisure time at youth centers they can play an active role in health promotion and be a health-promoting setting. There is a lack of studies where leisure time and especially youth centers are seen as a setting for health promotion. Therefore this study focuses on two youth centers in two multicultural, socially deprived suburbs in Sweden. The study highlights strategies that are important for making youth centers a health promoting setting.

Aim

The aim is to explore what specific strategies two different youth centers use in their everyday work and discuss how these strategies are important for enabling youth centers to serve as health promoting settings.

Methods

The study employs a participatory and practice-based approach [19,20]. Close cooperation with the staff of the youth centers has been emphasized. They have been involved in designing survey- and interview questions, sampling, and data collection procedures. The approach also includes providing regular feedback to the youth centers. This is done for two reasons. The first is that people in a setting are experts on the setting, so their input improves the quality and relevance of a study. The second is that it is of great importance that the research results are of practical use for the setting, in this case the youth centers. The study gives leaders and members alike an opportunity to be heard and to contribute their perspectives, which can further improve the activities and the knowledge base more generally.

This study uses data collected at the two youth centers through individual interviews with leaders, and focus-groups interviews with young participants. Triangulation was used to achieve multiple perspectives [21]. The interviewees are prompted to reflect on various questions, a procedure that in previous studies has been perceived to be valuable. Knowledge is brought back at group level, which can contribute to the promotion of youth health and development in the activities included in the study. Included activities can be developed through the study, and thus be of benefit for the research subjects.

The study context

This study is part of a research program about NGOs that conduct alcohol and drug prevention work, a special venture financed by the Swedish government [19,20]. Therefor the included youthcenters was given based on this special venture. The current study is a part of a longitudinal study titled “Leisure time as a setting for alcohol and drug prevention”.

The two youth centers studied are located in suburbs of two top-ten (by population) cities in Sweden. Both suburbs are characterized by apartment blocks and a high proportion of people with immigrant backgrounds and lower socio- economic status. The participants in the youth-centers are Swedish born youths having foreign-born parents who live with both parents, often in crowded apartments with many siblings. Moreover they feel healthy, enjoy school and have good contact with their parents [22].

The first NGO, hereafter called T, is a community-based NGO. It has a youth center in the neighborhood administrative and commercial center, and shares localities with other community services. T’s activities are directed at young people aged 10– 16 years. The youth center caters to 12–16 year olds, and has recently begun offering afternoon activities for 10–12 year olds. T primarily has employed leaders. It receives long-term financial support from the municipality to run the youth center, which is a part of the NGO’s activities.

The second NGO, hereafter called V, is a nationwide NGO with many local chapters. The youth center is for young people between 13 and 18–20 years. Two other premises are used for young people up to 13 years: one for the youngest and one for 10–13 year olds. Another location in a nearby neighborhood is more of a family meeting place for all ages. The youth center is the only activity run by V in this particular suburb. V has few employed leaders, but many volunteer youth leaders. V applies annually for funding to support its activities, and the municipality finances part of its activities.

The youth centers provide both structured activities, such as dance groups, travel groups, help with homework, exhibitions and leadership training, and unstructured activities, such as playing games, watching TV/films and just hanging out. They also have both youth-driven and adult-driven activities.

Sample

Youth center managers were instructed by the researchers to select young people of different ages for the group interviews. There was to be one group of girls and one of boys per youth center location. V also chose young people from the mixed-age family meeting place in the nearby neighborhood, resulting in three groups of girls and three groups of boys in total. The managers recommended that the groups be homogenous with regard to gender instead of age. The groups consisted of three to five members with different ages (13–17 years), ethnicities, experiences and number of years at the center, totally 26 young people.

The managers of the youth centers were selected for the individual interviews, one female and one male. The sample for additional individual interviews was decided jointly by researchers and staff, but was to include both employed and volunteer leaders as well as both genders. One employed male youth leader and two volunteer leaders, one female and one male, were selected for V. For T, one male employed leader and one male volunteer leader were selected. In total, seven leaders were interviewed.

Data collection

The in-depth-interviews with the managers and the leaders were conducted by first author and second author in all but two cases. Two interviews were conducted by first author alone. The focus-groups interviews with the young participants were conducted by first author or second author. The interviews were held at the youth centers in February 2013, and recorded with the permission of the respondents. Both in-depth and group interviews lasted for around an hour.

Interview guide

The interview guide followed the longitudinal study’s research questions. It included questions about who participates in youth center activities and why. It also focused on what the young people gained, and what specific strategies the different youth centers use in their everyday work. Semi-structured interviews were used for both in-depth and group interviews.

Qualitative analysis

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. An inductive qualitative content analysis was performed to analyze both the in-depth interviews and the group interviews to describe variations by identifying differences and similarities in the interviews [23].

Interviews were analyzed from whole units. Meaning units were first identified in accordance with the study aim and then condensed. The condensed meaning units were then sorted into categories. When moving from meaning units to codes, too much information was lost, so it was decided to sort the meaning units directly into categories. Other researchers including the third author were included to validate and discuss the results and together create categories and themes. The condensed meaning units were color-coded according to which youth center the respondents belonged to and whether the respondents were staff members, female adolescents or male adolescents to be able to see if any categories were shared by all groups or were unique to a specific group. Findings from the interviews has been communicated with the youth-centers.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Swedish ethical committee’s regional board in Uppsala in January 2012 (reg. No. 2011/475).

Theoretical framework

Health-promoting settings

The theoretical framework guiding this study is the healthpromoting settings approach introduced in the Ottawa Charter (OC) on health promotion in 1986, which states that “health is created and lived by people within the settings of their everyday life, where they learn, work, play and love” [24]. Since then the concept has been developed, and today it is an element of several public health strategies [25].

The OC [24] identified five health-promotion action areas: (1) Build healthy public policy – which is about legislation, organizational change, and policies that foster equity and ways to “make the healthy choice the easy choice”; (2) Create supportive environments – which describes how society and parts of society organize work and leisure to be safe, stimulating, satisfying, and enjoyable; (3) Strengthen community actions – which involves setting priorities, making decisions, and using strategies that empower a certain community through self-help and social support; (4) Develop personal skills – which is about supporting personal and social development through information, education, and the development of life skills; and (5) Reorient health services – which involves transforming the health care system in the direction of promoting health development and meeting the cultural needs of the population. All of these except for reorienting the health services can be seen as relevant for leisure-time activities, and will be used as part of the theoretical framework for this study.

The concept of healthy settings is used in a variety of areas, for example, healthy cities [26], healthy schools [27], and healthy universities [28]. However, few studies address how the settingsbased approach applies to leisure time or NGOs, despite their having the potential to create and sustain health-promoting environments [29,30]. Moreover perspectives that view NGOs (such as sports clubs) as health-promoting settings can be found in different disciplines [7,31].

A setting is complex and open; you have to take into account the complex interaction between environmental, organizational, and personal factors, and therefore need to integrate health into the setting’s routines and core activity [25,32]. This complexity also makes it difficult to evaluate settings-based practice [33]. Local knowledge about the setting is a prerequisite for effective health promotion [34,35].

Positive Youth Development

When analyzing the result in this study we also refer to Positive youth development (PYD) which is grounded in developmental systems theory. PYD assumes that youth have the potential for positive change and focus on developing personal and social assets rather than reducing problem behavior [36]. We believe that PYD is a prerequisite for a youth center to be a healthpromoting setting, but is also a consequence of successful health promotion. It makes young people resilient in the face of different health-risk factors such as alcohol and drugs. There is broad knowledge about how development occurs, especially within developmental psychology. Research shows that certain features of the settings where adolescents spend time make a tremendous difference in their lives [36-38].

Research and evaluation efforts have linked eight features of developmental contexts to PYD: (1) Safe and health-promoting facilities; (2) Clear and consistent rules and expectations; (3) Warm, supportive relationships; (4) Opportunities for meaningful inclusion and belonging; (5) Positive social norms; (6) Support for efficacy and autonomy; (7) Opportunities for skill building; and (8) Coordination among family, school and community [39]. Our results are discussed in relation to these eight features.

Results

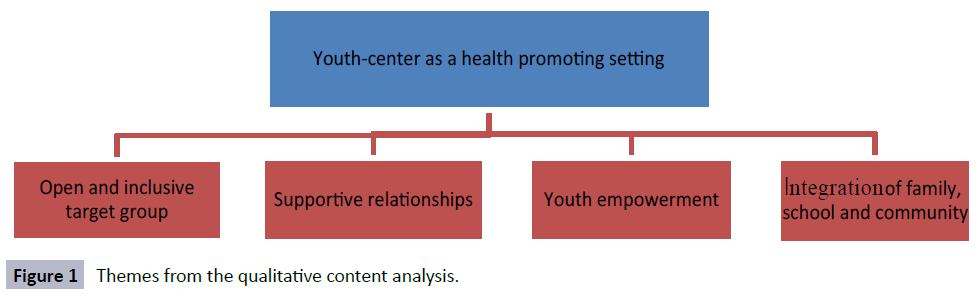

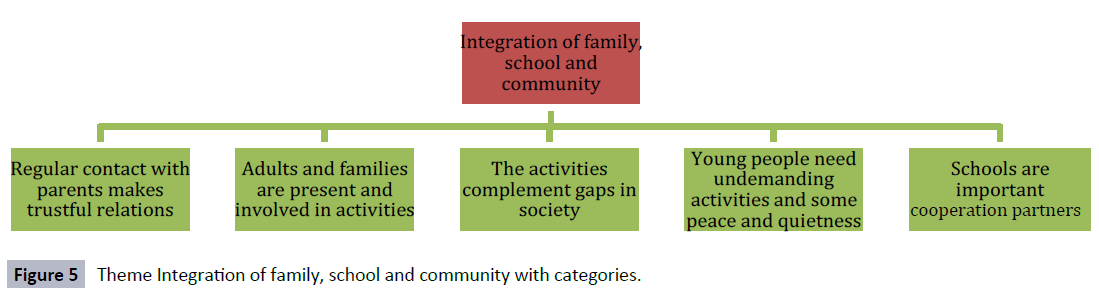

The research question on what specific strategies the different youth centers use in their everyday work resulted in four themes: Open and inclusive target group, Supportive relationships, Youth empowerment and Integration of family, school and community (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Themes from the qualitative content analysis.

Theme 1: Open and inclusive target group

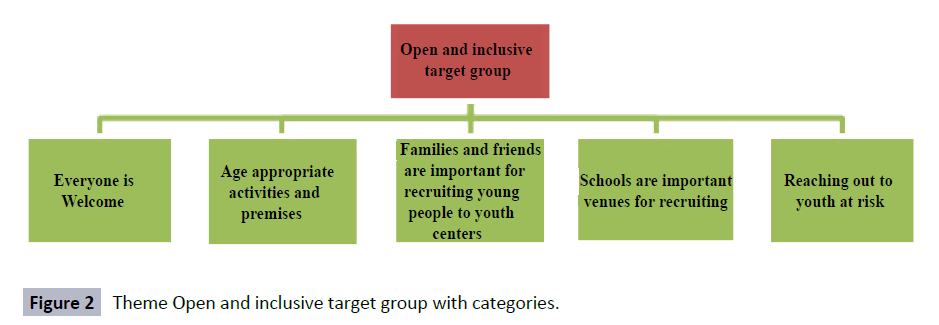

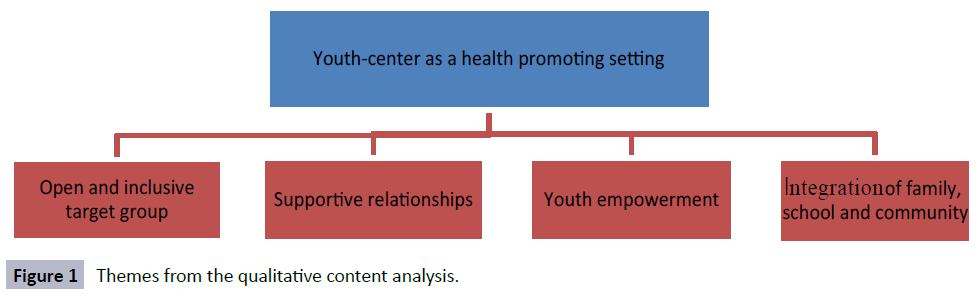

The first theme included five categories (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Theme Open and inclusive target group with categories.

Everyone is welcome!

Both youth centers have a broad and open attitude. Leaders and members alike point out that everyone is welcome. “You can come here whenever you like.” “It’s social, everyone’s welcome.” (Boys V)

Some say that they differ a lot from other associations in the area, because the others are often local ethnic associations. But here, all nationalities and religions are welcome. “We say that everyone has equal worth here. We don’t care whether you’re Muslim, Christian, Buddhist or whatever. We welcome everyone.” (Leader V) There is a mix of young people with different backgrounds and nationalities.

One leader emphasizes the importance of an open and inclusive environment for development.

“[...] When groups get too tight, we should split them up. I mean, when people speak their own language and don’t let anyone else in. You can never develop that way; it’s impossible. Instead you have to inject new life into it. This is something that our new leaders have understood. They also see that it has a positive effect when new people join. You get new angles on different viewpoints. Plus it’s fun getting to know new friends.” (Leader V)

Age-appropriate activities and premises

Both NGOs are open for all ages and emphasize intergenerational activities. At the youth centers they focus on high-school students, 13–18 years of age, but older youth are welcome to visit. They have no strict upper age limit, but when you reach an age of 19– 20 you get the message that you should move on to something else rather than taking space from younger participants.

Activities are also offered for younger children from 10 to 12 or 13 years old, either at different locations or different times. This offers a good basis for children to grow into the youth center’s activities. At some premises for the younger children, parents come together with their children; mostly it is mothers who also need to get out and socialize as one leader expressed it.

Before the youth center opened in one of the suburbs, many participants stopped attending when they reached the age of 13 because they thought there were too many children there. The leader therefore concludes that starting the youth center was the right decision. The adolescents sometimes want and need their own space, somewhere they can get away from parents, siblings or younger children.

“It’s nice that you can come to a place where people are going through the same period right now and are your own age, who understand and are more relaxed, and where you don’t have to adapt to adults.” (Girls V)

Recruiting through families and friends

Many of the young people have been members since childhood. They began coming to the children’s activities together with their parents. Then it continues for generations. They bring their sisters and brothers, their cousins and aunts.

“I've also been coming here for about as long as I can remember, since I was a kid. Because it’s like this, mom’s or dad’s cousins, friends who are in charge here and so on, you get pulled in and it’s a good place.” (Boys V)

Younger children often attend because of a fun activity. The older ones do so as well, but it’s more common that they come because of friends. Many hear about it through word of mouth. Young people talk highly of the youth center and its activities, causing friends and family members also to want to come and try it out. It spreads like rings on water.

Friends play an important role in deciding to come to the youth center or join a particular activity. Before coming, young people often send text messages to their friends to check if they will be there.

“Yes we’ve managed to bring several people along who ended up becoming members, because we do things with V during the summer holidays and such, and our friends see that, and they want to hang out with us, so they also become members ...” (Girls V)

Recruiting through schools

Both youth centers recruit through schools. The leaders regularly visit different schools during the day to establish connections with young people and provide information about activities at the youth center.

One strategy is to bring newcomers to the youth center during daytime school-breaks, so they can get used to the premises and meet the leaders when no one else is around. Then they feel more comfortable about coming back in the evening.

Reaching out to youth at risk

One youth center makes a special effort to reach youth at risk. Leaders hold “spontaneous walks” in the area. When they meet adolescents in unfavorable environments they talk with them and try to bring them to the youth center. Also, when visiting schools they try to reach those youth who seem to need it most. “We’ve chosen to concentrate on reaching and engaging with those children whom we see have a particular need for this.” (Leader V) Some young people voluntarily seek out the activities because they want to break with and change their social environment and friends.

Theme 2: Supportive relationships

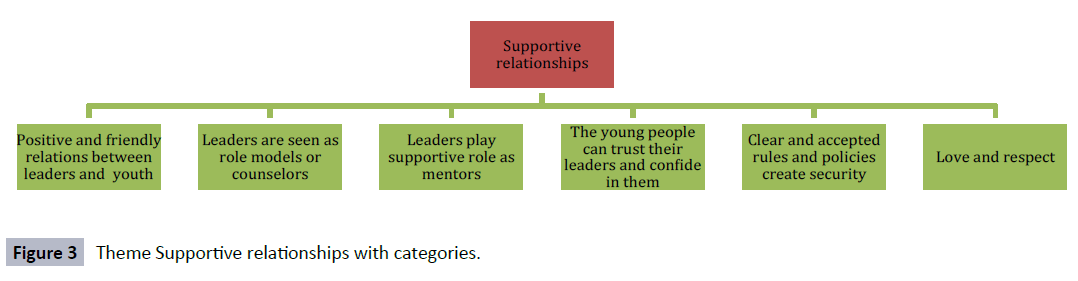

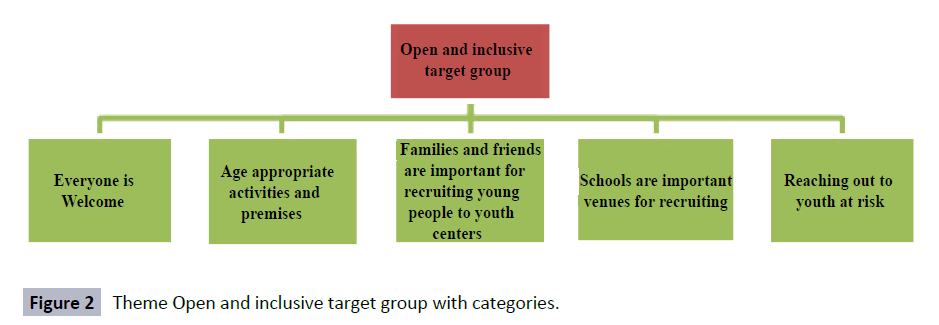

The second theme Supportive relationships were composed of six related categories (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Theme Supportive relationships with categories.

Positive relations between leaders and youth

The relationships among young people and between young people and leaders are very positive and friendly. The leaders are keen on maintaining a friendly and constructive atmosphere at the youth center. If something or someone threatens the positive atmosphere they intervene immediately and talk to the persons involved.

The leaders make a point of noticing and personally welcoming each young person every time they come to the youth center.

“Yes, we try to greet everyone here, to say hi. It’s almost obligatory. […] No one should come here and not be noticed. It’s an important task.” (Leader T)

“Every day when we come in the door they ask, ‘Hi M, how are you? Everything alright?’ That’s how it is, and you get an energy kick, feel glad and stuff.” (Boys T)

They young people appreciate and like their leaders. Some see the younger leaders as their friends. They also appreciate that they can joke with their leaders.

“That’s the good thing about it, that they’re leaders but we see them as friends too. We can see them from multiple perspectives. That’s what’s good because then several relationships are built up, and that’s what makes it so special.” (Girls V)

One of the leaders talks about the advantage of being nearly the same age as the participants.

“I'm not that much older than them which makes it much easier for me to adapt to their way of thinking. And so I think it’s easier to reach them. Both conceptually and in terms of action.” (Leader T)

Leaders are seen as role models

Leaders are seen as role models, and they often explicitly use the word. They train young people to become youth leaders and role models. The younger ones see their older peers as role models and want to grow up to be like them. The leaders also want to be role models and are very aware that the young people look up to them.

“[…] the leaders, I see them as role models so I also want to be like them [...] I also want to be able to take care of kids like they do, or be as social as they are.” (Girls V)

“I want them to see me as a role model. Not for the sake of my own self image, but for them to be able to walk in my footsteps. When it comes to change, when it’s time to stand up for themselves and make their voices heard.” (Leader V)

Some leaders do not see themselves as role models, but rather as counselors. They think that they are too old, that role models are people like Zlatan and Messi, and they do not want to compare themselves with them.

“[…] you rather hope that you might be some kind of guide, or leader or counselor. But I don’t think anyone would say you’re a role model.” (Leader T)

Leaders play a supportive role as mentors

The young people know that leaders are always around if they need them, and one of the leaders’ most important roles is to be accessible in relation to young people’s needs and desires.

“But you get a lot of questions, because you’re an adult. And they have concerns and they wonder about things. And so we try to answer in a helpful way. And no question is too silly or not serious enough to talk about.” (Leader T)

Another leader expressed it like this: “I think my most important role is to provide guidance. To be there, so they feel secure [....] so there’s someone they look up to who’s older, so they know we’re here. To be like a brother and a sister and a friend to everyone.” (Leader V)

The adult or older leaders also have experiences that they can share with the young people. For example one female youth leader plays an important role in supporting the girls.

“So I can say that these Mondays have helped me a lot with my problems, and how to live my life and so on ... and it’s perhaps the most important thing for me because I’ve received help. I think it’s something I appreciate.” (Girls V)

Another example is that leaders try to advise the young people in their educational decisions. They talk about the importance of school and encourage them to finish it.

“if you’re a bit unsure about what to do with high school and that kind of stuff, than you can come down here and talk with them. Yes, you get a lot of advice here, about what to do.” (Boys V)

The leader thinks that the young people have a need to be validated, both by their friends and by leaders, and that this need is fulfilled at the youth center.

Trust and confide in their leaders

When young people need someone to confide in, there is always a leader whom they trust and can talk to. They feel they can talk about anything with the leaders, including things they do not talk with their parents about. This applies especially with the youth leaders, who can be more like peers. Since the leaders know the young people very well and have a respectful relationship with them, they can discuss sensitive subjects with them. For example the girls can talk about very intimate things with a female youth leader. Their discussions are often about boys, relationships and sex.

The young people feel safe with their leaders, and feel that they can talk about honor-related questions that they cannot discuss with their families. Some think that their parents are too conservative.

“I have some girls who tell me secrets and so on, and they know that we have professional confidentiality, and it stays between us. And I’ve explained to them several times that I know what it’s like. I’m a girl so I know what it’s like to grow up in a special family with foreign background and they are a bit, they think differently. So I know that it might be hard and tough for you. You can’t talk to your mom or older sister about everything. So see me as a friend, not as an adult who works here, because I’m one of you. So we’ve had private conversations and I’ve sat and comforted some of them when they felt really bad. Others just want to get something off their chest and say ‘Oh I’ve met a guy and lalala’.” (Leader V)

Even though they can talk about personal and honor-related issues, many still think that there is a line when it comes to talking about family and home conditions that are considered private.

“Less frequently they may talk about their families, about their mom, dad and siblings, and what things are like at home. It feels like there’s a boundary there, that if you cross it, then you don’t just stand there talking about it; it’s rather something you want to talk about for real.” (Leader T)

Clear and accepted rules create security

The rules at both youth centers are clear, and are known and accepted by everyone. The rules are “like an automatic reflex” as one boy expressed it. The rules concern both practical things, like taking off your shoes, no alcohol or tobacco etc., and how to treat each other. The members have made the rules themselves. Some are written and hung on the walls, and some are spread by word of mouth. The members teach newcomers how to behave by showing them through actions, for example by letting younger kids play Fifa before older ones, so that they feel welcome and safe.

“They’ve made these rules themselves. It’s not something I came up with; it’s they who have said, ‘these rules should apply so we can get along together here at the center’.” (Leader V)

The young people are eager to preserve the safe and pleasant atmosphere so that they can feel at home. “No, everyone who comes here already knows [the policies]. Everyone takes care of this place; everyone sees it as a home. Like if you’ve eaten food, then you take care of the dishes” (Boys V).

One leader thinks that you should behave the same even outside the youth center, since you are seen as an ambassador for the organization, and people in the area know that you represent them. This view was shared by other leaders and young people at the center.

“You can’t be one person in here and another person out there, because if you’re one of us then you’re not just one of us at the center. You’re one of us out there also.” (Leader V)

If someone violates the policies, a leader speaks to the person immediately. The young people are very aware of what happen if you break the rules; you can be suspended from the center for some days. The young people report that since there are few problems with misbehavior and neglecting the rules, everyone feels very safe and secure at the center.

Love and respect

It is common for both young people and leaders to talk about love and respect.

“The volunteer leaders, but also the ones who are employed, have developed a sense for how to treat people. And as a leader you don’t just sit and watch TV, you’re active and talk to those who come here. You care, and show love. Because if you show love, you get love in return.” (Leader V)

The atmosphere taught the young people to welcome each other and show respect. The older ones are aware that the younger ones have respect for them, and act accordingly so the younger ones can feel safe.

“... they’re respectful, which I think is important. And you feel welcome when you come, because when we first came, started coming to V, it was older kids who welcomed us and I felt truly welcome.” (Girls V)

“I’m a bit older so I’m supposed to be a good role model for those who are younger than me who come to the center [...] so maybe I start talking with them, they might start to show respect, and then I also feel happy, and they’re like new friends, maybe a bit younger but still friends.” (Boys T)

The young people are taught to take care of each other and to show love and solidarity. The leaders say that by participating they learn how to relate to others, something that is beneficial in later life. It is important to talk with, not about each other.

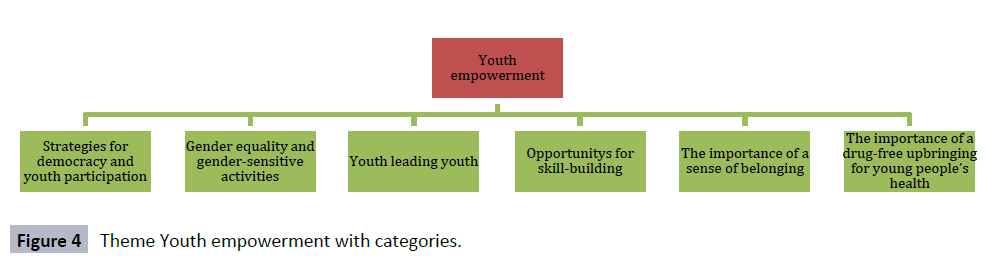

Theme 3 Youth empowerment

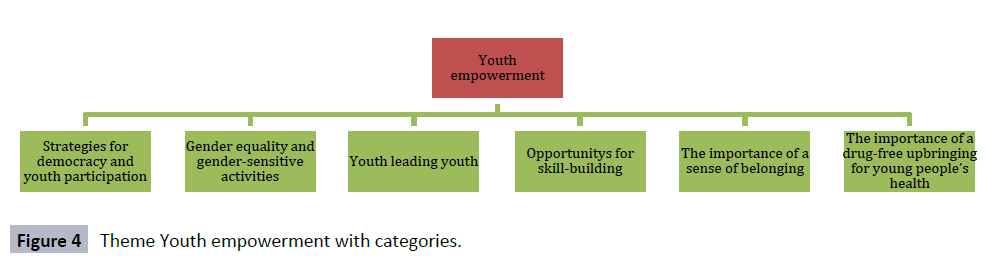

The theme Youth empowerment also included six categories (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Theme Youth empowerment with categories.

Strategies for democracy and participation

Both youth centers have a strong intention to foster young people in democracy, and promote their participation and influence. They use several different methods to encourage young people to be active and involved in shaping the organization and its activities. These can be anything from surveys, suggestion boxes, working groups and elections to taking part in meetings with politicians.

Members in one NGO have the right to vote at annual meetings from the age of seven. An evaluation is also performed every day; when the younger children go home they are asked what was good, what did not work so well, and so on. Monthly meetings are also held with the children to discuss what needs to be changed. The organization also encourages the young people to take part in external meetings with politicians and cooperation partners and express their opinions.

However the main way of promoting democratic ideals is to be responsive to young people’s ideas every day and to involve them in various activities. Giving them a sense of responsibility and confidence helps them grow and develop.

“When it comes to influence and participation, I believe that if you feel like you’re contributing you’ll feel more desire to give, to join in and participate and get more influence” (Leader T).

The leaders also emphasize the importance of openly discussing money and the financing of activities with young people, and of giving them quick feedback about suggestions they come up with.

The young people seem to be satisfied with their degree of influence and participation. They say that the leaders always listen to them and try hard to meet their demands and desires. “When they ask us to tell them what we want to do and maybe we say no, then they push us: come on, tell us, tell us” (Girls T).

However the leaders sometimes think that the young people could be more involved. They say that the floor is open to them but sometimes the young people lack the energy or desire to take advantage of it because they have too many demands and expectations in their lives.

“I think it has a lot to do with young people’s lives; they’re under a lot of pressure. There’s a lot coming from school, many demands from school, and expectations from sports leaders, from their families, so they can’t deal with more” (Leader T).

“There’s a lot we can do with our youth center. You just have to want to, have the will." (Boy T)

Level of involvement is quite similar between boys and girls and between different ages, even if girls and younger participants can be a bit more shy and withdrawn. The older they get the more confidence they have to express themselves. Girls also seem to be a bit more persevering in their commitments.

The leaders are also very aware of the fact that not all young people can or dare express themselves in front of others, so they always try other methods to reach those who are quieter.

“More girls are shy than boys overall. So it happens more often that we sit down and talk with the girls to find out what they really think. [...] To feel that everyone has equal influence. After all that’s our goal, even if we don’t always live up to it. But at least we try” (Leader V).

Gender equality and gender-sensitive activities

Both youth centers aim to promote gender-equality, though the boys may take a bit more space. They try to offer the girls activities that interest them; sometimes this means different activities at different times than those for the boys. The centers always try to give girls the same opportunity to make use of the resources. They offer special activities that have been requested by the girls such as girls’ nights, mother-daughter days, dance, and manicuring.

Each week one youth center has a regular girls’ night, when no boys are welcome at the youth center. This is highly appreciated by the girls. It is beneficial for their self-esteem and helps them to take more space on the other days as well. The female youth leader plays a central role for the girls. She encourages them to educate themselves, get involved, speak out and express themselves both at the youth center and in the world outside.

“And that’s why we constantly say how important it is that everyone takes the same amount of space.” (Leader V)

One youth center has an equal number of girls and boys. At the other center boys are overrepresented and some girls do not dare to come because of the boys. They also think that there are more activities for boys at that center. One leader says that since there are more boys many girls might feel that it is a boyish environment.

Youth leading youth

One youth center has an explicit strategy of youth leading youth. They pick young people who display leadership skills and train them to become youth leaders. They have around 20 youth leaders who take turns working on a voluntary basis on weekends to keep the youth center open. On Fridays and Saturdays, the youth center is usually crowded, and then the young people are on their own. They have adults on call in case something happens, but nothing ever does. Becoming a leader is very desirable; almost every young person wants to do so. They also have a rural study center where they regularly go for leadership courses. These are very popular among the young people and are much talked about.

“I’m completely convinced that our work with training young people to lead young people and be role models has a decisive effect [...] 22 youth leaders who are trained and are truly loyal, who are passionate about this, are giving their all for our members. It’s a strength” (Leader V).

“And then they come into a situation and act as leaders, and how they continue growing and how they receive the new members. And how seriously they take their role of being leaders. [...] They feel like ‘I matter to this’. They have a mission that they are proud of” (Leader V).

The other youth center can offer some members a course called “Older kids leading younger ones” that is provided by the municipality. This is appreciated, and the leaders think that it can be beneficial for the young people, for example in their summer jobs.

“It’s fun just being there, but being a leader, obviously it’s an honor. It’s fun just being around and seeing how the leaders work and how they treat the kids, and you want to be, to do exactly the same things as they do. It motivates you” (Boys T).

Opportunities for skill-building

The youth centers offer many opportunities for members to participate in skill-building activities. These can be anything from sports to different cultural activities. Activities are offered both on a regular structured basis and a more occasional unstructured basis. They give the young people opportunities to feel successful at mastering something.

“[the best thing with the youth-center]…for kids to have somewhere they can test things and experience things that would be hard to test and experience otherwise. And, for a period in their lives, to have had a place where they could develop, at an age when people develop quickly, yet to have had a place where they could do it in peace. But at the same time to get a lot of help with it” (Leader T).

“Above all you get self-confidence; you believe in yourself. Because everyone who is here is special in their own way. And that’s what distinguishes us [...] believing in yourself, daring to stand up for yourself. We’re not shy. Like C said, he used to be, but now he’s more open and dares to speak up among people” (Boys T).

“[the leaders]...they inspire us. They really want us to learn positive things here, for us to take control, uh, to be selfconfident” (Girls V).

There can also be courses with special themes. They regularly hold gatherings where they discuss different themes like gender equality, alcohol and drugs, and public speaking and argumentation. They also have leadership training and teambuilding activities at their rural study center.

Being a member of the youth center also implies gaining organizational knowledge and learning about community structures and different impact pathways. Leaders try to mentor the youth, for example in how they can raise an issue in the community, and encourage them to take active part in meetings with the municipality, politicians and other collaboration partners. One leader explains how a boy who used to be very shy and reclusive has grown up slowly and gradually by taking part in different meetings. First he was tense and nervous, but he has gradually become more secure and participates more fully in discussions. He has grown by learning how things are decided in clubs and associations.

By working on projects, for example preparing a trip, they learn to plan, take responsibility, develop strategic and teamwork skills, and work towards a goal.

The young people confirm that they have gained knowledge that will benefit them in their future life and that they have experienced things they never would have experienced without the youth center. At V many say that they have gained social competence.

One leader says that the activities mean a lot for the members “It means so much that some of them have found a job after this” (Leader V). They get qualifications and personal strength.

The leaders can see that members grow when given responsibility in different areas, for example handling sales in the café or watching over the children at a children’s party.

“...different kinds of arrangements, so the members can always help out and work if they want. And they usually think it’s fun, and you see how they grow with the responsibility. Different kinds of trips also cause them to grow a lot” (Leader T).

The importance of a sense of belonging

Many young people call the youth center their second home.

“The youth center, it’s like a second home. Where you feel secure [...] you feel at home” (Boys T).

Feeling a sense of belonging in the organization and being proud of one’s membership are more prominent at one youth center. There, leaders also talks about the NGO in terms of a large family where everyone knows and cares about each other.

“This feeling of being a family, the love that’s there, it’s a huge source of strength. It’s also the sort of thing that has kept me in the organization” (Leader V).

The members and their families are proud of the organization and “fight” to represent it, for example by wearing jackets with the organization’s name and logo. They say that the atmosphere at other youth centers is colder and less secure than at theirs, and that the others do not have the same close ties and sociable feeling as they have.

When working together on a larger project within the organization, the young people can experience a sense of belonging and feel like part of a wider context.

The importance of a drug-free upbringing

Alcohol, drugs and smoking are strictly forbidden in the activities and on the premises of the youth centers. These rules are well known and respected. For example, members know that the leaders will call their parents if they smoke outside the center or bring alcohol to a camp. All respondents testifies that there are no problems with alcohol, narcotics, doping or tobacco (ANDT) among the members and in the activities. The members think that the youth center has helped them avoid the wrong path, and that the center provides meaningful leisure time without any need for alcohol and drugs.

“And so you skip everything bad, like alcohol, cigarettes and such. Instead of partying on a Friday you can just come to the youth center and be with your friends, play Fifa and so on.” (Boys T)

One youth center has a very clear ANDT-strategy, for example as a common topic of discussion, both in the everyday work and in special courses and theme-discussions. The leaders believe that if you teach young people about the harmful effect of drugs and alcohol, they get a more restrictive approach to them. The strategy is to also reach youth in adverse environments and bring them into the center’s activities.

The boys explain that the leaders have told them since they were small that cigarettes and things like that are unhealthy, and therefore none of them smoke or have other harmful habits. Instead they stick to sports.

The other center does not have such an explicit strategy, but leaders there always take the opportunity to talk about ANDT when it pops up in everyday conversation or during everyday events, which the young people also confirm.

Girls say that they have learned about the consequences of drugs and how to resist peer pressure.

“I’ve learned to say ‘no’ to that, because I know the impact. I’ve taken classes; I’ve been in leadership training. I know. I see what happens. I see the consequences, and that is what I have learned here at V actually” (Girls V).

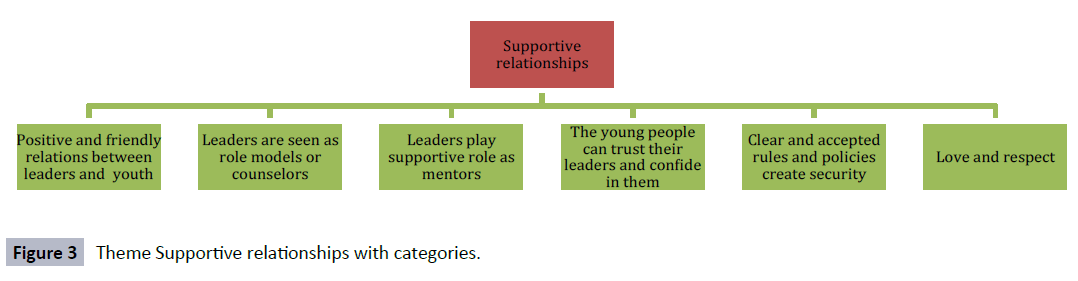

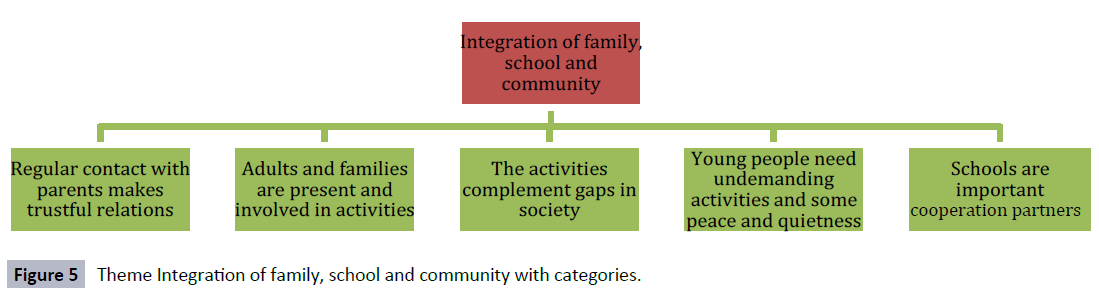

Theme 4 Integration of family, school and community

The last theme identified was Integration of family, school and community. It was composed by five categories (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Theme Integration of family, school and community with categories.

Regular contact with parents

The youth centers underline the importance of having good contact with members’ parents. They have many natural interfaces, places where parents can bring their younger children and meet each other, and various holiday activities in which many parents take part. They also have parents who take part in spontaneous walks in the area. When new people come to the activities, the leaders ask to meet their parents after a week. The members feel comfortable with their parents taking part in activities and visiting the center. Many even want the manager to visit them at home.

“...they almost know them personally, you could say, because we’ve been coming here since we were small. And mom always had to come then. So they’ve developed a relation with parents in that way.” (Boys V)

Some leaders find it harder to reach the parents, even though they try in different ways. They invite the parents to a free taco buffet, take part in parents’ meetings at school, and offer different activities for parents and children together. When they organize larger events and trips, they always contact the parents and inform them about it.

Many members live in families with honor culture which means cultural patterns that restrict people's rights and freedoms with respect to relatives honor. That makes it important for the family to have trust in the leaders and activities, so they will permit their children to take part. Some leaders have good and regular contact with the parents, which make them comfortable with permitting their girls to attend different activities. This is not the case for other activities arranged by the school or other youth centers for example.

“Monday is girls’ day. That’s the day when they empower each other, [...] to take space in the regular activities later. [...] Well, they come because they feel safe and secure here. Especially the girls; many of their parents don’t trust any other organization than this one.” (Leader V)

One leader believes there is a difference between boys’ and girls’ perceptions of the safe environment at the youth center, and mentions “how the families let their boys go there to a greater extent” (Leader T).

Adults and families involvement in activities

It is very common that adults and entire families take part in different activities, especially during holidays.

“They remain a while and socialize. Have coffee, talk, help the children do a puzzle or whatever they want to do, some mothers, sure. But other parents participate every day during holidays when activities are underway. They also come and participate. They come out, they help, they watch their children and they watch other people’s children too.” (Leader V)

One youth center makes special arrangements and holds bigger events where both parents and other adults take part and work together with the young people. The center is located near other facilities, such as the library, where adults are often present. They also have a cafeteria at the youth center open to everyone. The members are used to adults hanging around and have no problem with it. Sometimes pensioners help the young people with activities such as baking, painting, etc.

The activities complement gaps in society

Education is emphasize at both youth centers, because it is well known that doing well in school is one of the most important protective factors for young people’s future health. The centers offer encouragement and support with school, and help with homework. This gives young people the support and time they sometimes fail to receive from their school and/or their parents. Informal help can sometimes be easier to get from a peer or leader than from the teacher. “…it’s not that easy to go to high school and only get the help you get from school, because sometimes parents don’t have all the knowledge and access to support… “(Girls T).

They also complement the community’s social offerings, since they are open when other activities like school are closed. “... during holidays, weekends, and when the town shuts down, you could say that’s when we ramp up our activities” (Leader V). It is important for young people to feel they have somewhere to go where they can feel safe. Both youth centers are also an important actor in the community and collaborate with many other actors.

Young people need some peace and quietness

The leaders at the youth centers can see that members need a place where they can drop in and just hang out with friends, without doing so much more, because young people today are stressed and often feel pressure from school, parents, and society.

“... but mostly it just spreads happiness down there, like after a tough day at school or something, then you come down here and just relax, take it easy” (Boys V).

After school, the young people do not have the energy or desire to do so much. They also sometimes need less demanding and more easily accessible activities. Not all young people have parents who can drive them to activities in the city center. Therefore the youth center offers more unstructured activities close to where the young people live, so it is easy for them to take part and have fun without so many obligations.

“For example, dance is offered in the neighborhood, so you can go to dance class, for example, or play football without everything else associated with organized sports, that you must always come to practice, you have to have uniforms, sell bingo tickets, or whatever it might be. So you can do something you think is fun but in a simpler format” (Leader T).

“but many young people just want to be. They don’t need a lot to be happening all the time and things like that. They just want to sit and chill out and talk with each other and joke around a bit.” (Leader V)

Schools are important cooperation partners

The youth centers have good contact with the schools and cooperate with them. Leaders visit schools on a regular basis and participate in activities there. Since they have good contact with parents they sometimes serve as an important link between the schools and parents that the school has difficulty reaching. The manager sometimes accompanies parents to meetings at school so that they feel more comfortable.

“Then I can serve as kind of link, [I say to them] ‘I’ll come along to that meeting if you want to’. And then they dare to go, and you can sit and talk with the teacher or the principal and get a different viewpoint on the discussion, and above all they can reach the parents that they need to reach” (Leader V).

Discussion

Youth centers need to be open and inclusive towards their target groups, foster supportive relationships, emphasize youth empowerment, and integrate family, school and community in their strategies to be a health promoting setting. These themes are discussed below, theme by theme, in relation to previous research and this study’s theoretical framework.

Our results show that four of the five health-promotion action areas in the OC [24] are relevant and applicable to the youth centers. The results also show that both youth centers are characterized by a high level of the eight features of development contexts that are linked to PYD [37,39].

Open and inclusive target group

The center should be open to all, so that everyone feels welcome and included, and the participating youth testified that they were so. But it is also important that different ages and groups have appropriate activities of their own, so that they can get the most benefit. This can be achieved by having different locations or schedules for activities with a different focus. This correlates well with PYD’s Opportunities for meaningful inclusion and belonging. The OC action area Create supportive environments – how to organize leisure to be safe, stimulating, satisfying, and enjoyable – also fits very well with the youth centers’ work and how members perceive the activities. Even though our study shows, in line with other research [5,40], that peers and friends are important during adolescence, we also find that family is important when it comes to leisure-time activities. This is in line with Geidne and colleagues [22] who showed that good contact with parents is especially important in a neighborhood with many immigrants with diverse views of society’s institutions. One extra dimension that were raised where that mothers while bringing their kids to the premises also were offered opportunities to come out and socialize which could be seen as positive for the integration on immigrant women. Good contact and cooperation with schools are also important for reaching young people. The study shows in line with previous research [3] that the young people live and develop in a context where family, peers, community, society and culture all influence their leisure-time.

Even though both the leaders and young people say that the centers are open to everyone, there is a risk that newcomers and people outside the inner circle feel less welcome. Many members have known each other since childhood and are very tight with each other. Moreover, some girls also testify that they do not feel welcome because of the boyish environment.

Supportive relationships

Safe and supportive families and schools, together with positive and supportive peers, are crucial for young people’s health [3]. Adolescents have a greater need of contact with and support from peers and adults other than their parents [40]. Promoting supportive relationships is central in both OC and PYD, and both centers showed good examples of it. In some activities the young people exercise control but adult leaders play supportive roles as mentors and facilitators. The adult leaders provide intermediate structures when needed. The members felt that the leaders were caring and responsive, that they provided useful guidance, and that they were important people whom they could rely on. This also fits well with the OC’s supportive environment.

The quality of relationships with adults is a critical feature of any developmental setting [37]. This can comprise warmth, connectedness, good communication and support. It can also include adults as good mentors and as caring and competent adults. In this study the relationships between young people and adults were very good and the young people experienced support from their leaders. This fits well with PYD’s Warm, supportive relationships. Some young people think they can have stronger relationships with leaders who share their backgrounds and interests.

The youth leaders are seen as good role models by members, since they share the same values and have been fostered in the same context. The young people appreciate having peer leaders who are their age, come from the same area, and can understand and relate to their situation. The members of V think that their leaders are like friends; at T the adult leaders put more emphasis on the importance of being “adult” in their work.

In relation to Safe and health-promoting facilities, linked to PYD, the youth centers provide a physically and psychologically safe environment that is free from violence, unsafe health conditions, and harassment.

For OC’s recommendation Build healthy public policy we find that the centers have well-developed policies and rules that help members make healthy choices, for example not to drink alcohol or smoke on weekends when attending center activities. The rules are explicit and are accepted. Everyone knows that they should treat each other with honesty and respect. When attending activities, the young people are met by a structured environment. They also have opportunities to provide input in creating rules and structures, which correlates well with PYD’s Clear and consistent rules and expectations.

The high sense of safety during activities was due to the center’s clear and consistent rules and appropriate supervision, even though the local environs and the route to the center were not always safe. There were also some differences between girls and boys concerning the safety of the youth center. Some girls mentioned feeling insecure because of the boys’ attitudes and behavior. Letting the girls have their own day has been a way to strengthen the girls’ self-confidence and self-esteem. It has also provided a good opportunity to talk with the boys about how this is related to their behavior. It should also be said that the female youth leader plays an important role in the success of “girls’ day” and in the girls’ appreciation of it.

Concerning PYD’s Positive social norms, the impact of peer norms on adolescents can be both positive and negative. Regarding antisocial behavior, what activity a young person is involved in and with whom he or she does it are both significant, because it may be better not to be involved at all than to participate in unstructured activities, especially if they include a large number of deviant youths [16]. Therefore social norms can be crucial in a youth center setting. The youth centers in this study seem to have succeeded in creating and maintaining positive social norms. This is visible in both the organization’s formal structure and the informal culture that arises from daily interaction. The members are maintaining the positive social norms by teaching newcomers and younger members how to behave and interact respectfully with others.

Youth empowerment

Develop personal skills/Opportunities for skill building are also central to both OC and PYD, and the study finds that these are part of the youth centers’ main strategies. The study found plenty of methods and opportunities to develop the young people’s life skills and support their personal and social development through information and education. The skill-building opportunities includes cognitive, physical, psychological, social and cultural skills. This is also emphasized by the United Nation [6]. The young people report receiving life-skills that they can take with them in their adult lives.

When it comes to PYD’s Support for efficacy and autonomy, young people are agents of their own development. To foster development, settings need to be youth centered and provide young people the opportunity to be efficacious and to make a difference in their social world. This includes opportunities to make a real difference in their community, to experience meaningful challenges, to be empowered, and to receive support for increasingly autonomous self-regulation [37].

The centers foster their members in democracy, providing encouragement and rich opportunities for them to get involved, participate and exert influence, both within the youth center and in the broader community. Opportunities to be involved in complex tasks and decision making, which are needed for optimal development both in school and in the family environment [41], are just as important in leisure-time and are provided at the centers. Members are given positions of responsibility in different activities, which makes them grow, and they feel that they make meaningful contributions. In this study, young people are powerful agents of personal change and community development.

Both centers show good examples of gender equality and gendersensitive activities, even though we found room for improvement. It can be a huge challenge to find strategies and methods to reach girls, or for that matter other underrepresented youth. Boys are overrepresented and the girls feel that the boys take too much space and resources, which is a recognized problem in many similar meeting places for youth [42].

A sense of belonging is important for young people’s well-being and health. In relation to PYD’s Opportunities for meaningful inclusion and belonging, many members call the youth center their second home, which can be seen as a clear sign of belonging. They also see themselves as a large family. A sense of belonging to a group can give positive self-esteem and stronger ego identity, but it can also imply exclusion or hostility in relation to others [37]. Nevertheless there are no signs of this in this study, rather the opposite, because both youth centers and their members have a broad and open attitude and welcome everyone to their fellowship. Because the youth centers are NGO driven, they are governed by their associations’ basic ideas and vision. They also offer a larger context within the parent organization. This gives good chances for a strong sense of belonging.

Also connected to rules and appropriate supervision are the strategies for dealing with ANDT. When this is included and discussed in the everyday work at the youth center, members get a more restrictive attitude toward ANDT. The study shows that the youth centers provide the young people with many protective factors against ANDT abuse. The interviewed youth are very clear about their negative attitude towards ANDT. Results from the longitudinal study also show that young people at the two youth centers feel healthy, almost none of them use tobacco, and only a small proportion have tried alcohol [22]. One center had a clearer and more out spoken ANDT- strategy. Apart from internal work with the young people about ANDT and its harmfulness they also play a very active role within their community and collaborate with different networks to combat the criminal drug trade in the area. This was raised in the interviews both from leaders and the young people. The other center´s strategy to work ANDTpreventive where not so obvious in the interviews neither with the leaders nor the young people.

The members can experience leadership responsibilities, and develop strategic and teamwork skills. V provides a gradual progression for members, where they move from adult-driven to youth-driven activities as they develop the necessary skills. The young people go through a period of training in which adults teach them leadership skills that they then apply while the adults step back into a supportive role. A strength and added value is that the youth center is run by an NGO. Otherwise it would have been difficult to let the young people themselves be responsible for keeping the center open on Friday and Saturday evenings.

The young people testify that they feel more empowered, competent and motivated to strive towards distant goals, such as their future occupation. They also reported that the skills they acquired carried over to other parts of their lives, for example in the form of wider social networks and greater social competence.

The youth centers in this study are good places for young people to spend their leisure-time, places where they feel valued, respected, and challenged in positive ways. The youth centers cultivate a culture of fairness and opportunity among their members. The centers are youth sensitive and youth centered. The leaders listen to the young people and obtain feedback from them, and show great understanding for their desires and wishes.

The centers provide opportunities for the young people to be academically engaged, feel emotionally and physically safe, to have a positive sense of self or self-efficacy, to develop life and decision-making skills, and finally to do so in a physically and mentally healthy environment, all of which, according to Blum and colleagues [43], are goals for healthy adolescence.

Integration of family, school and community

Our last theme also links well with both OC’s Strengthen community actions and PYD’s Coordination among family, school and community efforts. Crucial to youth development is that there is communication between the different settings of an adolescent’s life and a shared understanding of his or her needs. Both youth centers display in this study good contact with their members’ families, schools and surrounding community. At V they often speak of social control all day long, meaning that they follow the young people from morning (at school) to late in the evening, when they take spontaneous walks in the area or when the young people go home from the youth center.

When it comes to OC’s Strengthen community actions, both youth centers collaborate with many different parts of their community, and are well known and appreciated by the community. They also receive funds from the municipality for their efforts to help strengthen the community.

In Sweden 65% of children between 10 and 18 years of age feel stressed at school because of homework or tests, or because of high demands from parents, from teachers, or from themselves [44]. This verifies our finding that young people need undemanding activities and some peace and quiet.

General considerations

The adult leaders had clear goals and well-developed strategies for how to work towards them. They had a clear vision that they wanted to promote good health. One leader expressed it as they want to help them to grow by offering activities. They don’t offer activities in order to keep them from doing crazy things, but for them to see for themselves that it brings good things.

The results are presented through examples of what the leaders say in theory about their strategies and example of how they practice their theories. Then the outcome of the practice – what the young people say about their experience of the youth centers, is presented. At both youth centers it is very noticeable that the young people confirm what the leaders say about theory and practice. It is evident that most of their strategies and theories are working well.

Even though the leaders at the two youth center express the same things in theory, the theory sometimes seem to have more practical impact in V. The outcome is stronger and clearer. This could be because leaders at V seem to identify more strongly with their ideology and values, which help to succeed better with their approach. It could also be that young people at V have been members since childhood, and have been fostered in the organization’s core values and approach. For many years V has also had a charismatic leader who personifies the organization’s core values.

The centers provide a good mix of structured and unstructured activities. Since young people report having many demands in their lives, they need unstructured activities where they can feel relaxed and a convenient place to hang out with friends and just be. Still, the unstructured activities are provided within a safe and inclusive environment with clear rules and where adults and leaders play supportive roles.

Our findings are similar to a recent review of youth sports clubs as health promoting settings [31]. Sports clubs as well as youth centers have plentiful opportunities to be health promoting settings, but to do so they need to include and emphasize certain important elements in their strategies and daily practices.

We can also view our findings within an ecological framework, where the goals of a healthy adolescence are to be academically engaged, to be emotionally and physically safe, to have a positive sense of self or self-efficacy, to possess life skills and decisionmaking skills, and to be physically and mentally healthy [43]. Youth centers can help young people fulfill these goals by adopting key strategies.

These youth centers appear to be good examples of well-run and meaningful leisure-time activities for young people. Participants receive plentiful opportunities to become healthy adolescents with strong resilience against unhealthy behavior such as alcohol, drugs and tobacco use. The centers provide activities that can teach young people a great deal. Some themes emerged that seem to be important for youth development and positive health, and we believe these may be applicable to other youth centers that aim to be health promoting settings for youth. Many of our findings replicate findings from past research which is a strength. In future research it would be interesting to explore and compare different leisure time settings such as youth centers run by community and leisure-time activities in for example sport clubs or cultural organizations.

Methodological discussion

One could discuss whether the focus-groups interviews gave more or less information than individual interviews would have done. We believe that the interaction between participants provided breadth in the answers, and that it was a cost-effective form of data collection. Since it was 26 young people in total with mixed ages and sex we believe that the groups can be seen as representative even though the fact that the manager choose the participants for the focus-groups interviews could be seen as a bias problem. Interpreting interviews requires knowledge about the context in which a study is conducted [45]. The interviewers in this study were also the persons who analyzed the interviews. Strength of the study is that the researchers have been familiar with the NGOs’ activities for many years. Strength is also the triangulation achieved by reporting from multiple stakeholders as leaders and youth had concordant views on the strategies at the youth centers, and reinforced each other’s statements. The young people repeatedly confirmed what the leaders said. A weakness is that only two youth centers were included in the study. If the study had included more youth centers or other neighborhood youth, the results could have been richer, however we believe our results can be applicable to other youth centers that aim to be health promoting settings for youth.

Practical implications

Although the two youth centers operate in quite similar contexts, there are some structural differences between them that need to be taken into account when comparing data. These concern such things as employed versus volunteer leaders, and different economic conditions.

Even though we observed features that are important for PYD and health, these must be translated when applied to other contexts and into another center, program or activity with a different population of young people, different organizational goals, etc. Every youth center has its unique setting, and exists within a distinct organizational and community context. We believe that some added value comes from the fact that the centers are run by NGOs. For example it could be difficult for a youth center run by the municipality to allow youth leaders to keep the center open on weekends without an adult leader present. Still we believe that the strategies we have found in this study can be applicable to other youth centers that aim to be health promoting settings for youth.

Conclusions

The study shows that youth centers have good prerequisites to be or become health-promoting settings. But it is not given; not all youth centers are automatically health-promoting settings. The current study points out some factors that are important to include in their strategies and that need to be included both in theory and in the daily practice. To be a health-promoting setting, a youth center needs to be open and inclusive towards its target group, foster supportive relationships, emphasize youth empowerment, and integrate family, school and community in their strategies.

Acknowledgements

The study could not have been conducted without the help of the engaged and interested staff and young people at the two youth centers Verdandi in Rinkeby- Tensta and Föreningen Trädet in Örebro.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived and designed the study. Data were collected by IF and SG. IF prepared the initial interpretation of qualitative data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. IF and SG drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by a grant from the Swedish Public Health Agency.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing or financial interests.

8425

References

- Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, et al. (2012) Adolescence: a foundation for future health.Lancet 379: 1630-1640.

- Due P, Krølner R, Rasmussen M, Andersen A, TrabDamsgaard M, et al. (2011) Pathways and mechanisms in adolescence contribute to adult health inequalities.Scand J Public Health 39: 62-78.

- Viner RM1, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, et al. (2012) Adolescence and the social determinants of health.Lancet 379: 1641-1652.

- Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, et al. (2008) Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries.N Engl J Med 358: 2468-2481.

- Wiium N1, Wold B (2009) An ecological system approach to adolescent smoking behavior.J Youth Adolesc 38: 1351-1363.

- United Nations (2003) World Youth Report 2003. The Global situation of young people.

- Kokko S1, Green LW2, Kannas L3 (2014) A review of settings-based health promotion with applications to sports clubs.Health PromotInt 29: 494-509.

- Reardon-Anderson J, Capps R, Fix ME (2002) The Health and Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families. The Urban Institute. Series B, No B-52.

- Sletten MA (2010) Social costs of poverty; leisure time socializing and the subjective experience of social isolation among 13–16-year-old Norwegians. J Youth Stud. 13: 291-315.

- Statistics Sweden (2009) Barn i dag - En beskrivningav barns villkor med Barnkonventionensomutgångspunkt.

- Blomfield CJ, Barber BL (2011) Developmental Experiences During Extracurricular Activities and Australian Adolescents' Self-Concept: Particularly Important for Youth from Disadvantaged Schools. J Youth Adolesc. 40: 582-594.

- Swedish national institute of public health (2011) Social health inequalities in Swedish children and adolescents - a systematic review, second edition. Stockholm.

- Eccles J, Barber BL, Stone M, Hunt J (2003) Extracurricular Activities and Adolescent Development. J Soc Issues. 59: 865-889.

- Simpkins SD, Ripke M, Huston AC, Eccles JS (2005) Predicting participation and outcomes in out-of-school activities: similarities and differences across social ecologies. New Dir Youth Dev.2005:51-69.

- Bartko WT, Eccles JS (2003) Adolescent Participation in Structured and Unstructured Activities: A Person-Oriented Analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 32:233-241.

- Mahoney JL, Stattin H (2000) Leisure activities and adolescent antisocial behavior: The role of structure and social context. J Adolescence. 23:113-127.

- Cooper H, Valentine JC, Nye B, Lindsay JJ (1999) Relationships Between Five After-School Activities and Academic Achievement. J Educ Psychol.91:369-378.

- Larson R, Walker K, Pearce N (2005)A comparison of youth-driven and adult-driven youth programs: Balancing inputs from youth and adults. J Commun Psychol.33:57-74.

- Eriksson C, Geidne S, Larsson M, Pettersson C (2011) A research strategy case study of alcohol and drug prevention by non-governmental organizations in Sweden 2003-2009.Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 6: 8.

- Eriksson C, Fredriksson I, Fröding K, Geidne S, Pettersson C (2014) Academic practice–policy partnerships for health promotion research: Experiences from three research programs. Scand J Public Health. 42:88-95.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2007) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousands Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Geidne S, Fredriksson I, Dalal K, Eriksson C (2015) Two NGO-run youth-centers in multicultural, socially deprived suburbs in Sweden – Who are the participants? Unpublished results. Health. 7: 1158-1174.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 24:105-112.

- Dooris M (2004)Joining up settings for health: a valuable investment for strategic partnerships? Crit Public Health.14:37-49.

- deLeeuw E1 (2009) Evidence for Healthy Cities: reflections on practice, method and theory.Health PromotInt 24 Suppl 1: i19-19i36.

- St Leger LH1 (1999) The opportunities and effectiveness of the health promoting primary school in improving child health--a review of the claims and evidence.Health Educ Res 14: 51-69.

- Dooris M, Doherty S (2010) Healthy universities-time for action: a qualitative research study exploring the potential for a national programme. Health Promot Int.25:94-106.

- Geidne S (2012) The Non-Governmental Organization as a Health promoting Setting: Examples from Alcohol Prevention Projects conducted in the Context of National Support to NGOs: Örebro University, Sweden.

- Kokko S (2010) Health Promoting Sports club. Youth sports clubs' health promotion profiles, guidance, and associated coaching practice, in Finland. University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

- Geidne S, Quennerstedt M, Eriksson C (2013)The youth sports club as a health-promoting setting: An integrative review of research. Scand J Public Healt. 41:269-283.

- Dooris M (2009) Holistic and sustainable health improvement: the contribution of the settings-based approach to health promotion.Perspect Public Health 129: 29-36.