Keywords

Child health, neonatal, Nepal, South Asia, women

Introduction

Child mortality rates like the neonatal mortality rate, infant mortality rate and under five mortality rate are important indicators of a country’s socioeconomic development as well as health status. In September 2000 the United Nations set eight Millennium Development Goals to be achieved by the year 2015, of which the fourth goal aims to reduce child mortality rate by two thirds. Of the 9 million under-five child deaths per year, more than 41% occur during the neonatal period, the period up to 28days after birth, therefore improving newborn care is essential for further progress [1].

Of the three million neonatal deaths annually almost 75% die within one week and almost 50% on their first day of life. Globally three causes account for three quarters of neonatal deaths: infections (36%, which includes sepsis/pneumonia, tetanus and diarrhoea), pre-term (28%), and birth asphyxia (23%) [1]. Lastly, virtually all (99%) neonatal deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, especially Africa and South Asia.

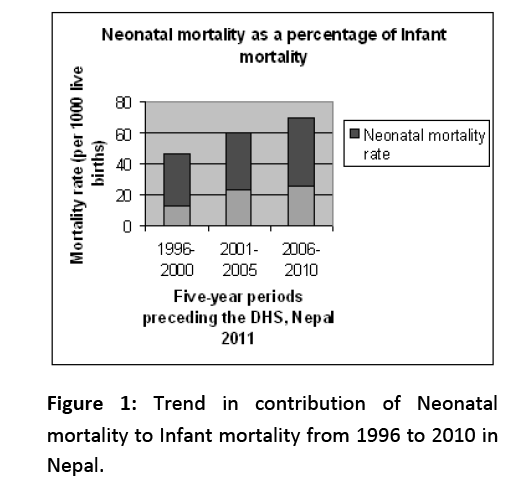

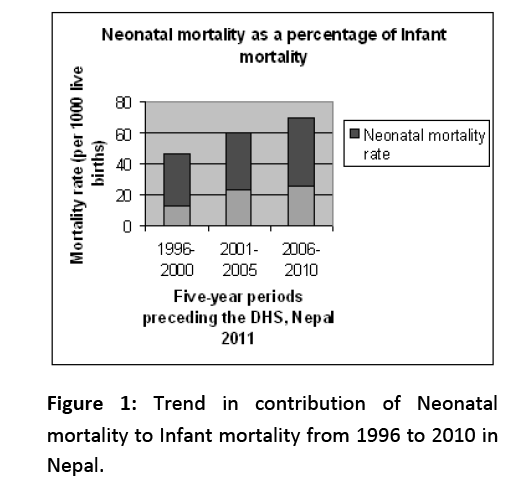

The most up-to-date statistics for Nepal is the neonatal mortality rate of 33 deaths per 1,000 live births; eight times that of developed regions (4 deaths per 1,000 live births). This rate is two and a half times the post neonatal rate (13 deaths per 1,000 live births) [2]. Between 1996 and 2006 infant and child mortality rates in Nepal dropped by 31% and 57% respectively [3]. Yet neonatal mortality has decreased at a slower pace, resulting in rise of neonatal deaths over the past 15 years from 63 percent of all infant deaths to 72 percent and from 42 percent of under-five deaths to 61 percent (Figure 1) [2]. Nepal’s pace of reduction of the neonatal mortality rate suggests that reaching the neonatal mortality target of 16 per 1,000 live births for 2015 is going to be a serious challenge [3].

Figure 1: Trend in contribution of Neonatal mortality to Infant mortality from 1996 to 2010 in Nepal.

The objective of this article was to review the major challenges in improving neonatal health in Nepal and to identify possible keys to achieving Millennium Development Goal 4.

Methodology

Electronic databases including MEDLINE, Popline, Scirus, Google Scholar, BioMed Central and HINARI were searched exhaustively for studies related to Nepal. Selection criteria included the period 2002 to 2012 and English language articles only. Although most literature cited was specific to Nepal, articles from other countries which examined neonatal health and health-seeking behaviour were reviewed to gain a broader perspective. Furthermore publications from the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation and Ministry of Health of Nepal websites were also accessed to find relevant reports and papers. Published and unpublished organizational reports, relevant articles and some grey literature were also included.

Results

The literature suggests that the following significant challenges: (1) antenatal care; (2) delivery practices; (3) postnatal care; (4) limited health infrastructure; (5) transport and communication; (6) affordability; (7) women's empowerment; and (8) political instability.

Antenatal care

Neonatal and maternal mortality are closely linked, and the risk of dying from neonatal conditions can be reduced with quality care provided during pregnancy and childbirth.4 According to the Nepal DHS 2011 report only 50.1% of pregnant women had at least four antenatal visits as recommended by the National Safe Motherhood Program and 15% women had none, due to reported barriers to seeking care being shyness towards male health workers, restriction on mobility for women, need was not perceived by the husbands’ family or due to financial and transport constraints [2,5].

Additionally, there is limited awareness of available and required health services. For example, two doses of tetanus toxoid vaccine given to women during pregnancy to prevent deaths from neonatal tetanus is received only by 69.7% mothers, even though provided free of cost at government health centres [2]. Even amongst those who receive antenatal care many are not educated on subjects like diet, cessation of smoking and drinking, or signs of pregnancy complications, leading to neonatal complications. In certain communities, like Tamang, the consumption of alcohol and smoking during pregnancy is common practice, which might increase preterm delivery, low birth weight and intrauterine growth restriction, stillbirth and neonatal mortality [6].

Delivery practices

Pregnancy is regarded as a fragile, vulnerable state, yet childbirth is considered a natural event with social and religious ramifications, not a medical event. In Nepal, 63% of deliveries take place at home, with 7.5% occurring in the backyard or cow shed, increasing the risk of infection and sepsis [7]. Only in the event of complications are newborns taken to health centres causing a delay in obtaining critical care. In Nepal only 36% deliveries are attended by a skilled birth attendant, including doctors, nurses, or midwives. The rest have deliveries conducted by those who cannot provide basic resuscitation in asphyxia or manage newborn complications, leading to death, otherwise preventable [2].

Little attention is paid to hygiene during delivery as a 2006 survey in western Nepal found 48.3% birth attendant/s do not wash their hands [7]. Although Clean Delivery Kits (CDK) are currently distributed in Nepal only 14.1% use it and the umbilical cord is cut with a new or boiled blade in 68% of deliveries and in 15.2% deliveries a sickle, household knife, or khukuri (a traditional knife) was used. The stump of umbilical cord was dressed with oil, turmeric and antiseptics in 41.2% deliveries which can lead to neonatal sepsis [7].

There is decreased knowledge regarding wiping and wrapping of baby immediately after birth, leading to death due to neonatal hypothermia. In a study most of the respondents (84.4%) burnt firewood for heating the room, but 34.8% did not wipe their babies after delivery, 38% of the respondents bathed their babies within one hour and only 18.3% of respondents bathed their babies after 24 hours [8]. In a Western Nepal survey, 73.8% of newborns were wrapped in an old washed cloth [7].

In a cross-sectional survey in Eastern Nepal, it was shown that all the newborns are breastfed but only 57% initiated breastfeeding within one hour of delivery and 9% had discarded the colostrum [9]. In a few communities ghee, oil, honey, sugar or animal milk was given to the newborns before the initiation of breastfeeding since it is believed to “clean out the babies insides” by making them pass a stool. But these substances when contaminated may cause infection [9].

Postnatal Care

Newborn care to identify, manage, and prevent complications is essential. The Government of Nepal recommends at least three postnatal checkups within seven days of delivery, yet 68% newborns do not receive them as few communities tend to perceive complications in newborn as “God’s wish” [2]. Many cultural practices can increase the risk of infection like topical applications to the cord, and in a study it was found that throughout the neonatal period, 80.4% infants received at least one application of mustard oil, others had application of ash, mud, breast milk, saliva, water, herbs and spices, while 15.4% received home made antiseptics [10]. Application of kajal or surma (kohl) to newborns’ eyes, believed to ward off the evil eye or make eyes beautiful, can lead to watery eyes, itchiness, allergy and infection [11].

The prevalence of exclusively breastfeeding at 1, 3 and 6 months were 74%, 24% and 9% respectively and few mothers do not receive any information on breastfeeding during their antenatal visit, resulting in a missed opportunity [9,12]. Water and local herbal drops (janamghuti) were the two most commonly introduced drinks in first two months, followed by local semi-solid porridge (lito) and powdered milk [9]. If these foods, or the vessels they are prepared or stored in are contaminated, or when prepared with unwashed hands may cause infections in the neonates. Hand washing with soap is the most effective intervention against diarrhoea that can affect both the mother and child, with a 47% reduction in diarrhoea [13]. It should be reinforced during antenatal care that exclusive breastfeeding has an impact on reducing child mortality [9]. Apart from care after birth, family size and short inter pregnancy intervals are also critical factors which do not receive their due attention [5].

Limited health infrastructure

Most women in villages visit the health post or sub-health post, most of which are not provided with facilities for routine antenatal screening like blood and urine tests, proving impossible to identify high risk mothers like gestational diabetes mellitus or pre-eclampsia, associated with risks to foetus. Most health posts lack calibrated infant weighing scale and records of low birth weight babies. In most hospitals in villages, there are no incubators or radiant warmers, required especially for preterm and LBW (low-birth weight) babies. Even the government hospitals in urban areas of Nepal can be poorly equipped, discouraging families from using such services. Unlike many other developed countriesthe availability of neonatal ventilation is still in its infancy and the basic infrastructure and expertise to ventilate newborn is lacking in majority of hospitals [14].

Lastly, the larger hospitals in Kathmandu absorb women and their babies from all around the valley, leading to delay in an appointment and it is impossible to have privacy [5,15]. There is shortage of skilled attendants who can recognise complications and provide care for newborns [14].

Furthermore, there is an unbalanced distribution of health personnel, the more skilled concentrated in urban areas, and inaccessible to rural populations where it is most needed. Due to factors in health care system like low remuneration, heavy workloads, poor infrastructure and working conditions, and factors outside health care system like lack of security, crime, taxation levels and repressive social environments, health care professionals do not want to work in Nepal and tend to migrate abroad in search for a better quality of life, educational opportunities and higher pay. The increasing emigration of health care workers in Nepal contributes to a shortage of trained health professionals [16].

Transport and communication

Poor women avoid seeking health care if they are faced with large distances to cover, or seek care from less trained providers who are more accessible. In most hilly regions in Nepal there is no easy access to motorable roads, so poor women have to walk hours in their pregnant state for health checkups [5], and 14% of women do not deliver in a health facility because they are faced with transportation problems [2]. Newborn complications can occur if women deliver on the way to hospital, and during delivery at home or at a primary health centre in trying to reach the ambulance. Telecommunication problems also exist in many rural areas where there is no telephone service. Mobile phones are often with the head of the family as married women live in extended families, and if in the event of complications, the head of the household is unavailable no one can be called for help.

Affordability

In Nepal the percentage of people living below the international poverty line (earning less than US$1.25 per day) was 24.8% in 2011 [17]. Health services finance is categorised: those from public expenditure and those from user pockets. In Nepal DHS 2011 5% reported financial cost as a barrier in receiving skilled care, and the risk of dying among children gradually decreases with increasing household wealth [2]. Most cannot afford the direct costs needed to pay for the services, investigations, drugs, procedures and transport and indirect costs in the form of the loss of the women’s household duties, reported as lying between 1-5% of annual household expenditures [18].

Women in the highest wealth quintile (92%) are almost three times as likely to receive skilled care as women in lowest wealth quintile (33%) [2]. The average expenditure in a hospital stay is NRS 11,400 ($128) and the health payments can include medical supplies (gauzes, gloves, bleach and bed sheets) and non-medical costs that include food, living expenses and payments given as a tip: 85% give informal payments ranging from NRS 50 ($0.56) to 100 ($ 1.12) to low-level hospital staff (ward attendants) [19]. These out-of-pocket expenditures are between 5 and 34% of annual household expenditures and can force households into poverty, especially if neonatal complication costs arise [18]. Thus, even if families can physically access healthcare often money can act as the next barrier to seeking care for their newborn.

Lack of women's empowerment

Though the third MDG is to promote gender equality Nepalese women have low status in society. Marriage occurs relatively early in Nepal, with the women’s median age at first marriage being 17.5 years [2]. Women are not allowed to go against their parents’ decisions and social norms force teenagers to give birth before they are emotionally or physically ready. In South Asia, the recorded teenage pregnancy rate is second highest in Nepal (21%) [26]. There is lower uptake of antenatal care facilities by pregnant teenagers due to lack of physical and mental maturity and majority are unaware of the process of conception and dangers of unplanned pregnancy [20]. Risk of pregnancy complications: low birth weight, pre-term delivery, still birth, foetal distress, birth asphyxia, anaemia, pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) and spontaneous abortion, is 2.5 times higher among pregnant teenagers compared to mothers in their twenties [20].

The limitations in mobility and educational opportunities leads to limited access to health related information. The use of health care services from a skilled provider is strongly related to the mother’s level of education; women with a School Leaving Certificate (and higher) are twice as likely to receive health care from a skilled provider (89%) as women with no education (42%) [2].

In most homes the decision regarding seeking health care are made by husbands or older females, which prevents women from seeking care for their own health or their babies. Nepalese husbands may not be willing to send their wives for medical checks when only male doctors are available. Older women like mothers-in-law may not prefer health facilities since they do not think it is necessary [5]. Power relations also mean that women need to ask the male head or the mother-in-law money for health care services. Finally, according to Nepalese culture the nurturing role of women is pervasive and is expected regardless of circumstances. Mealtimes mean that women, even during pregnancy, have to wait until all members of her family finish eating, this delay results in eating the leftovers and can affect the health of the fetus [5].

Political instability

The country recently emerged from a decade-long violent conflict (1996 to 2006) between Maoist rebels and the government, which affected both the population’s health and the health care system. It led to destruction of many health posts in rural areas, and the killing, harassment, kidnapping, threatening and prosecution of health workers by the warring factions [3]. The conflict also hindered health programmes implemented by non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Conflict impacts negatively on the health of population, however, in Nepal progress was made as access to health services increased. Thus in spite of the violent conflict, Nepal made progress in 16 out of 19 health indicators over the period 1996-2006 (among them the child and maternal health indicators). Lessons were adopted from the conflict to include marginalized groups (Dalits and women) to increase coverage of the health programmes in more remote and underserved areas, emergency funds and community drugs schemes. It was during the conflict that the government implemented the community-based newborn care package [3,21].

Discussion

Evidences suggest that the factors outlined below need to be considered to improve neonatal health in developing countries like Nepal.

Improving Antenatal Care

For better child survival preparation for delivery should be made before hand. The challenge of delivering messages to promote maternal and newborn health in the terai region of Nepal was addressed through training Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs), who are provided with a pictorial booklet to educate women about frequency and timing of antenatal visits, requirement of tetanus toxoid vaccination, iron tablets, improved diet, avoidance of smoking and alcohol, rest and reduced workload; and help in the recognition of, and appropriate responses to, maternal and newborn danger signs. Arranging for a skilled birth attendant, choice of facility, saving for care in case of emergency and transportation are also important aspect of birth preparedness [22].

Enhanced Delivery Care

Delivery attendance by skilled personnel is one of the indicators of the fifth Millennium Development Goal (to improve maternal mortality), which needs to increase drastically to MDG5 target of 60% by 2015 [3]. As infection accounts for 40% of neonatal deaths, they should be taught the five cleans during delivery which WHO emphasizes: clean place, clean surface, clean hands, clean cord and dressing, and a clean tie [23]. There should be an enhancement in the ability of the FCHVs to care for the baby born at home, like teaching suctioning of mouth and neonatal resuscitation, to assist newborns with asphyxia. The NGO ‘Save the Children’ trains local women to deliver basic life-saving care to mothers and children in their communities when the doctors and nurses are out of reach [24].

As of 2011, the Community-Based Newborn Care Program in Nepal has been implemented in 15 districts, recommending: (1) wiping the newborn immediately after birth to prevent hypothermia; (2) skin-to-skin contact between baby and mother’s chest (the so-called “kangaroo” method); (3) early (within the first hour) initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding up to six months; (4) not applying anything on the cord stump; and (5) bathing the newborn only after 24 hours [2]. This programme has to be expanded to cover entire Nepal, along with usage of a sterile delivery kit for home deliveries, which contains a blade, a bar of soap, three cord ties, a plastic coin for cord cutting, a plastic sheet [25]. Kit use is associated with reduction in neonatal mortality, however use of a clean delivery kit is not always accompanied by clean delivery practices, which if followed are significantly associated with reductions in mortality, independently of kit use [26]. Hand washing should be promoted by birth assistants and mothers during the first 2 weeks after birth [27].

Adoption of better postnatal care practises

The newborn should receive at least three postnatal checkups within seven days of delivery, for both home and hospital deliveries, as recommended by the Government of Nepal [2]. Families should be explained the danger signs in newborn, like fast breathing, inability to feed, excessive sleepiness, high or low body temperature, rashes using pictures and advised to visit the health facility. Harmful applications to cord should be avoided. Chlorhexidine cord cleansing applied consistently over the first 10 days of life can reduce umbilical cord infection [10]. However as mentioned above the Community-Based Newborn Care Program in Nepal recommends not to put anything on the cord. Education on the importance of breastfeeding and how to feed children especially during illness can have a beneficial impact on the child health and nutrition. Furthermore as a behavioural change can be a cost-effective intervention, if applied to the context in which women work, i.e. agricultural labour in some instances three days after birth in Nepal, can improve nutrition and reduce neonatal deaths [12].

Improving health infrastructure

More investment from the Government towards healthcare facilities countrywide, especially in difficult terrains is necessary. The health system effectiveness should include up to date evidence based care on correct diagnosis and antibiotics. The protocols need not be highly technical; they could include provision of basic screening tests and the substitution of low-technology radiant heaters and room heaters for expensive incubators [28]. Additionally, a revision of medical education needs to include training health care providers to listen to needs and fears of future parents, and issues of privacy and confidentiality should be emphasised [5].

However, though preventive and good curative intervention should be the priority, emergency and critical care facilities should also be developed proportionately. Neonatal mortality could be reduced theoretically by adding Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU) at a few key hospitals.

The funds would have to be diverted from adult care, for equipment purchase, maintenance and repair.An urban public hospital in Nepal presented a cooperative model of creation (funding, planning and execution of training) and transfer of technology from the West, which was successful in the establishment of NICU in this hospital [29]. Further, investment from the government towards the training of healthcare personnel and attractive working and salary conditions to prevent doctors and nurses emigrating is required [5].

It is necessary to improve the resources and neonatal intensive care services with an appropriate ratio between sick neonate and medical staff [14]. Training parents to participate in the NICUs may ease the problems of trained nursing staff shortage. Family-centred care is becoming a standard of care in NICUs worldwide. Viewing the family as the child's primary source of support, has been associated with numerous benefits including decreased length of stay, enhanced parent–infant attachment and bonding, improved well-being of pre-term infants, better mental health outcomes and better allocation of resources, in addition to fewer lawsuits and greater patient and family satisfaction [30].

Nurses assume an important role in the context of NICU, because they develop collaborative work with the physician in the strategies and decisions, provide direct care to the newborn and give support to the family. The nurse has a fundamental role concerning the involvement of the parents in the activities of postnatal and NICU care, promoting the participation of the parents in the care, guiding and encouraging them to handle their children. The nurses involve parents in the care, sharing their doubts, fears and uncertainties and, consequently, generating warmth and security and facilitating the parents being with the child, so they can feel confident and integrated into the role of father and mother in the recuperation of the child [31]. Finally, strategies to keep newly trained nurses in Nepal are necessary and perhaps research can help to establish what factors would keep Nepalese nurses in the country.

Improving communication and transportation system

The provision of ambulances by the healthcare sector in Nepal can ensure high-risk deliveries or newborns with complications to be referred to well-equipped facilities in time [5]. In parallel to a transport network, the road infrastructure in the hilly areas should be improved or better equipped health posts and mobile clinics should be ensured.

Telecommunications if subsided in remote areas can enable mothers to report complications in newborns to health personnel. Mobile phones play an increasing role in developing countries in terms of ‘mobile health’ like an NGO project collected mobile phones in UK and donated these to women’s health promotion groups in Nepal [32].

Making services affordable

It is necessary to increase, from the existing 6%, the allocation of the national budget to health services [18]. To encourage ANC attendance and institutional deliveries the Safe Delivery Incentive Programme was launched in 2005, which is Nepal’s maternity cash incentive consisting of NRS 400($4.49) for four or more antenatal visits [33], NRS 300 ($3.37) if a skilled attendant conducts the delivery and between NRS 1,000 to 1,500($11.2 to 16.85) for institutional delivery [18]. If this initiative receives countrywide coverage and targets rural populations it would encourage women, and their families, to seek a safe delivery [33,34]. Incentive schemes cannot be taken to be a prodigal magic bullet as there exists weaknesses in incentive schemes however, as women are often not aware of these schemes and a concomitant increase in institutional deliveries overwhelm staff [17].

Developing national policies that ensure the removal of financial barriers and reducing fees for essential services, as they prevent seeking of skilled care, should be Government priority. For instance medicines should be provided free of cost during postnatal health checks and their subsidisation should be ensured as user fees would deter parents from seeking care. This is the biggest challenge as progress is least made in fragile states, where Nepal is a country in transition to democracy post-conflict [3].

Improving women’s status in society

Improving women's educational status is the best strategy to improve the women’s status, and eventually neonatal health. As previously discussed, the mother’s education is inversely related to a child’s risk of dying. Education could play a significant role in developing self-confidence, increasing age at first sexual intercourse and delaying marriage and consequently avoiding teenage pregnancy. Making education free and compulsory to girls will significantly improve the received care and neonatal survival [15]. Compulsory sex education to both girls and boys can help to empower the girls, which is the most effective strategy to prepare them for planned and delayed pregnancy and better motherhood.

The parents must be apprised of the need to involve girls in marriage-related decisions and made aware of the physical and mental health dangers of early marriage [20]. Similarly, involving women in decision-making processes within the family can help them to use the health services. Community education must encourage families and individuals to delay marriage and first births until women are physically, emotionally, and economically prepared to become mothers.

Health promotion

Health promotion is one of the most cost effective health interventions. It is important to increase awareness among the general public as well as among primary care health workers that deliveries are best conducted by skilled health personnel in a hygienic environment [35]. Health promotion should focus on raising awareness among the general public regarding potentially harmful cultural practices and the danger signs during pregnancy, delivery and child care. Evidence shows that informing women about the benefits of antenatal and postnatal care, danger signs/symptoms during pregnancy and in neonates, and advice to seek emergency care when needed, is essential [36].

It is imperative to advocate the use of family planning methods to space or limit births to help mothers focus their care on the newborns. There should be materials, designed at an appropriate literacy level, containing answers to the questions most frequently asked during pregnancy to take home for women and shared with their spouses. Between 1996 and 2006 contraceptive use increased nationally by 25%, ANC visits by 49% and tetanus toxoid uptake by 30% due to health promotion [3]. Finally, more structural changes are needed too, including a better understanding among healthcare workers on informal payments, that these can create perverse incentives and thus potentially reduce motivation to reform [18]. Also an improved transport and health infrastructure would help improve the health of women and neonates in Nepal, but we should not forget that Nepal is the 17th poorest country in the world, suggesting that transport and infrastructure improvements will generally be slow. For example, there are a growing number of nursing colleges and, consequently a growing number of qualified nurses, but too many seek employment abroad.

Involving men in health matters

Too often maternal health interventions are gynocentric, we recommend that information regarding women's and newborn’s health needs should also reach the husbands, as they are the main decision makers in the household [15]. In Nepal volunteers explain to husbands their duty to share the workload of wives during pregnancy and after delivery, allowing adequate rest to women and involving them in care of the newborn. A study in rural Bangladesh found that husbands whose wives utilised skilled delivery care provided more emotional, instrumental and informational support to their wives. In contrast, husbands whose wives utilized an untrained birth attendants at home were uninvolved during delivery and believed childbirth should take place at home according to local traditions [37]. Compulsory sex education is equally important for boys as it is for girls, to increasing age at first sexual intercourse and involving in protected sex to space births. In Nepal, the husband and the mother-in-law roles are intangible in decision making, if both are encouraged to be involved in making joint decisions with the mother, and her access to monies with regards to antenatal and neonatal health, it may provide an important strategy which ultimately helps to reduce the neonatal mortality [38,39].

Conclusions

The key medical interventions are well known: improving women’s health during pregnancy, appropriate care for newborn at birth and care for the baby in the first weeks of life. Also, interventions are needed that not only address medical problems but also social, dietary, financial and cultural issues that act as barriers to seeking care. Ancient cultural practices, limited resources and administrative capacity in the health service, however, create serious challenges to the Government of Nepal to achieve the fourth millennium development goal. Changing behaviour and cultural norms is difficult, as seen to be highly prevalent during pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding.

An important intervention is providing comprehensive health promotion, especially in rural communities, to women and families regarding care before and after delivery of newborns through appropriate training of healthcare workers. The cost-effective feasible interventions, that health promotion interventions can target, should include: initiating breastfeeding within one hour of birth and exclusive breastfeeding up to six months, proper cord care and keeping the baby warm after birth and awareness of danger signs to then seek care with availability of antibiotics and special care to those children with low birth weight.

Furthermore, interventions should focus to improve the status of women in society including increasing female literacy and empowerment. Additionally, it is essential that skilled health workers are present at every birth including those in rural settings. The availability of quality care and quality emergency neonatal care and the referral system are equally important. Attracting newly trained doctors and nurses to stay in the country and improving the health, communication and transport infrastructure at an affordable cost are basic prerequisites for neonatal health. Finally, interventions recommended for Nepal may also work in other low-income countries in Asia.

2946

References

- World Health Organisation. Newborn death and illness. 2011. Available from: https://www.who.int/pmnch/media/press_materials/fs/fs_newborndealth_illness/en/ Accessed on 2012 June 15

- Nepal demographic and Health Survey 2011. Ministry of Health and Population Government of Nepal, New ERA. Kathmandu Nepal and Macro International Inc. U.S.A., 2012.

- Devkota B, van Teijlingen E. Understanding effects of armed conflict on health outcomes: the case of Nepal. Conflict and Health 2010; 4(1):20.

- Lawn J E, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C, Massee Bateman O. Newborn survival in low resource settings?are we delivering?. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics &Gynaecology 2009; 116(1): 49-59.

- Simkhada B, van Teijlingen ER, Porter M, Simkhada P. Major problems and key issues in Maternal Health in Nepal. Kathmandu University Medical Journal 2006; 14(4):258-263.

- Kesmodel U, Wisborg K, Olsen SF, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ. Moderate Alcohol Intake during Pregnancy and the Risk of Stillbirth and Death in the First Year of Life.

- Sreeramareddy CT, Joshi HS, Sreekumaran BV. Home delivery and newborn care practices among urban women in western Nepal: a questionnaire survey. BMC Pregnancy and childbirth 2006;6(1):27.

- Devkota MD, Bhatta MR. Newborn Care Practices of Mothers in a Rural Community in Baitadi, Nepal. Health Prospect 2012;10(1):5-9.

- Ulak M, Chandyo RK, Mellander L, Shrestha PS, Strand TA. Infant feeding practices in Bhaktapur, Nepal: A cross-sectional, health facility based survey. International Breastfeeding Journal 2012; 7(1):9.

- Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Adhikari RK al. Risk Factors for Umbilical Cord Infection among Newborns of Southern Nepal. American Journal of Epidemiology 2007; 165 (2): 203-211.

- Baby Center. Is it safe to apply 'surma' or 'kajal' to my newborn's eyes? . 2012. Available from: www.babycenter.in/baby/newborn/surma-kajal-expert/ Accessed : 2012 Aug 22

- Walraven G. Health and Poverty: Global Health Problems and Solutions. In Earthscan. UK; 2011.

- B Conway G, Waage J. Science and Innovation for Development. In Improving Health/ DFID UKCDS. UK; 2010.

- Gurubacharya SM, Aryal DR, Misra M, Gurung R. Short-Term Outcome of Mechanical Ventilation in Neonates. Journal of Nepal Paediatric Society 2011; 31(1):35-38.

- Sharma S. Reproductive Rights of Nepalese women: Current status and Future Directions. Kathmandu University Medical Journal 2004; 2(1):52-54.

- Dussault G, Franceschini M. Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Human Resources for Health 2006; 4(1): 12.

- The World Bank. Nepal Country Overview. 2012 Available from https://go.worldbank.org/4IZG6P9JI0.Accesed : cited 2012 July 30.

- Richard F, Witter S, De Brouwere V. Reducing financial barriers to obstetric care in low-income countries. Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp Press. Belgium; 2008.

- Simkhada P, van Teijlingen E, Sharma G, Simkhada B, Townend J. User costs and informal payments for care in the largest maternity hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. Health Science Journal 2012;6(1): 317-334.

- Acharya, DR, Bhattarai R, Poobalan A, van Teijlingen ER, Chapman G. Factors associated with teenage pregnancy in South Asia: a systematic review. Health Sciences Journal 2010; 4(1): 3-14.

- Devkota B, van Teijlingen E. Why Did They Join? Exploring the Motivations of Rebel Health Workers in Nepal. Journal of Conflictology 2012; 3(1):18-29

- Mcpherson RA, Tamang J, Hodgins S, Pathak LR, Silwal RC, Baqui AH et al. Process evaluation of a community-based intervention promoting multiple maternal and neonatal care practices in rural Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2010; 10(1):31.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. Reading Material for ASHA: Maternal & Child Health. NRHM. 2006; pp18.

- Healthy Newborn network. Newborn Resuscitation in Nepal. 2012 Available from https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/blog/photo-week-newborn-resuscitation-nepal Accessed : 2012 Sept 2

- Morrison J, Tamang S, Mesko N, Osrin D, Shrestha B, Manandhar M et al. Women's health groups to improve perinatal care in rural Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2005; 5(1):6.

- Seward N, Osrin D, Leah L, Costello A, Pulkki-Br?nnstr?m AM, Houweling TA et al. Association between Clean Delivery Kit Use, Clean Delivery Practices, and Neonatal Survival: Pooled Analysis of Data from Three Sites in South Asia. PLoS Medicine 2012; 9(2): e1001180.

- Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Adhikari RK et al. Risk Factors for Umbilical Cord Infection among Newborns of Southern Nepal. American Journal of Epidemiology 2007; 165 (2): 203-211.

- Wright N. The Evaluation of a Low-Technology Radiant Heater for Low-Income Countries: Project B. 2005 Available :https://www.leeds.ac.uk/nuffield/documents/bscprojectb/05wright.pdf Accessed : 2012 Nov 29.

- Adhikari N, Avila ML, Kache S, Grover T, Ansari I, Basnet S. Establishment of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care Units at Patan Hospital, Kathmandu: Critical Determinants and Future Challenges. Journal of Nepal Paediatric Society 2011; 31(1): 49-56.

- Cooper LG, Gooding JS, Gallagher J, Sternesky L, Ledsky R, Berns SD. Impact of a family centered care initiative on

- NICU care, staff and families. Journal of Perinatology 2007; 27(2):S32-37

- Merighi MAB, Jesus MCPD, Santin KR, Oliveira DMD. Caring for newborns in the presence of their parents: the experience of nurses in the neonatal intensive care unit. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 2011; 19(6): 1398-1404

- Bournemouth University. Mobile phones for Nepal. The Beacon 2010; 12(1):6-7.

- Minca M. Midwifery in Nepal: In-depth country analysis. Unpublished Background document prepared for the State of the World?s Midwifery Report 2011. May 2011.

- Powell-Jackson T, Morrison J, Tiwari S, Neupane BD, Costello AM. The experiences of districts in implementing a national incentive programme to promote safe delivery in Nepal. BMC Health Services Research 2009; 9(1):97.

- vanTeijlingen E, Simkhada P, Stephen J, Simkhada B, Woodes Roger S, Sharma S. Making the best use of all resources: developing a health promotion intervention in rural Nepal. Health Renaissance 2012; 10 (3): 229-235.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report: make every mother and child count. Geneva; 2005.

- Story WT, Burgard SA, Lori JR, Taleb F, Ali NA, Hoque DM. Husbands' involvement in delivery care utilization in rural Bangladesh: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2012; 12(1):28.

- Mullay BC, Hindin MJ, Becker S. Can women?s autonomy impede male involvement in pregnancy health in Kathmandu, Nepal? Social Science and Medicine 2005; 61(9):1993-2006.

- Simkhada B, Porter MA, van Teijlingen ER. The role of mothers-in-law in antenatal care decision-making in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010; 10(1):34.