Keywords

Female sex workers, Sexu al and reproductive health, Integration, Health system

Abbreviations

FSW: Female Sex Workers; SRH: Sexual and Reproductive Health Services; SAT: Southern African AIDS Trust Zambia; STIs: Sexually Transmitted Infections; YHHS; Young, Happy, Healthy and Safe

Introduction

In sub-Sahara Africa, young people, in particular females remain among the worst affected by HIV, yet all too often at the periphery with regard to accessibility to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services [1]. For example, by 2012, the adult HIV prevalence in Zambia was 12.7%, and the prevalence among young women aged 15-24 was more than twice that of men in this age category [2,3]. Although the relationships between HIV and SRH are well recognized, young women still face difficulties in accessing SRH services [4,5]. Difficulties in accessing SRH services tailored to meet the needs of young people often results in marginalisation of this group, who frequently end up being treated in adult services. Poor accessibility to SRH services in most low and middle-income countries has resulted into as many as 60 per cent of the young women having unintended pregnancies and births [6], as well as an increase in presence of STIs which has subsequently resulted into a decline in health and an increase in the likelihood of HIV transmission and re-infection for these young people.

Studies in most low and middle income countries have indicated that access to SRH services is even poorer among the ‘hard to reach’ groups which include young people living with HIV and female sex workers (FSWs). The SRH needs of young people living with HIV are largely unmet, resulting in widespread misconceptions and misinformation regarding fundamental aspects of prevention and reproductive life [7-9].

In Zambia sex work is not typically connected with large-scale brothels. It usually occurs without intermediaries or gatekeepers. Sex work in Zambia is criminalised. The clients of sex workers generally represent a broad cross-section of society, and most sex workers and their clients have other sexual partners [10]. Some of women who consider themselves sex workers, and other women who receive money or goods in exchange for sexual services see their work as “business” [11].

The high poverty and employment levels have affected FSWs’ accessibility to health services in Zambia. According to the 2007 Zambia Demographic Health Survey about 44% of the young people are unemployed. Because of poverty, some of the young women have been forced into health risky behaviours such as sex work [12]. The actual number of FSWs and prevalence of HIV among FSWs in Zambia is not known because under Zambian law sex work is illegal [13]. Under Zambian law, it is illegal to solicit customers or live off the earnings of someone engaged in sex work. Section 147 of the Zambia Penal Code states that: every woman who knowingly lives wholly or in part on the earnings of the prostitution of another or who is proved to have, for the purpose of gain, exercised control, direction or influence over the movements of a prostitute in such a manner as to show that she is aiding, abetting or compelling her prostitution with any person, or generally, is guilty of misdemeanour.

Female sex workers are often arrested and detained for loitering which creates a ‘work’ environment under which FSWs live and work in fear of bullying, harassment, arrest, extortion and sexual abuse at the hands of the Police. FSW are also generally despised, marginalised and discriminated against in the communities they live and work in; and by workers in the health services. This often undermined sex workers’ ability to access health services in general but particularly those for the treatment and prevention of STI’s including HIV. Because of these restrictions studies focusing at sex workers’ access to and usage of HIV services are lacking.

Although clients of FSWs contribute to the HIV prevalence, Zambia did not have comprehensive SRH programmes for FSWs as sex work mainly due to the illegal status of sex work. This limited availability of SRH programmes negatively affected accessibility by FSWs to SRH services [14]. Providing SRH services that target young FSWs is important because as these FSWs negotiate the transition from childhood to adulthood, they may require additional support in order to confront issues related to stigma and discrimination and anxieties about the future [7].

In 2013, the International HIV/AIDS Alliance’s Africa Regional Programme supported a project aimed at improving access to SRH services among FSWs in Chipata district. This innovative approach was called the Emerging Voices project. The project was innovative as it aimed to improve access to SRH services through integrating friendly SRH services for FSWs into the health system at district level. Innovations refer to new ideas, programmes, projects and health technologies which are perceived as fresh by the adopting individual, community or unit [15,16]. While some innovations are in hardware form [17,18] others such as SRH services targeting FSWs can be seen as a critical part of the health system’s software. Unlike other approaches for improving access to SRH services, the Emerging Voices project was classified as an innovative approach because, to the best our knowledge, it was the first approach to specifically focus at meeting the SRH needs of FSWs through the use a multisectoral Task Force and former FSWs know as queen mothers. The Task Force consisted of key stakeholders that network with FSWs in the district such as health workers, the police, NGOs and religious leaders. The FSWs were also represented in the Task Force.

The health system in Zambia

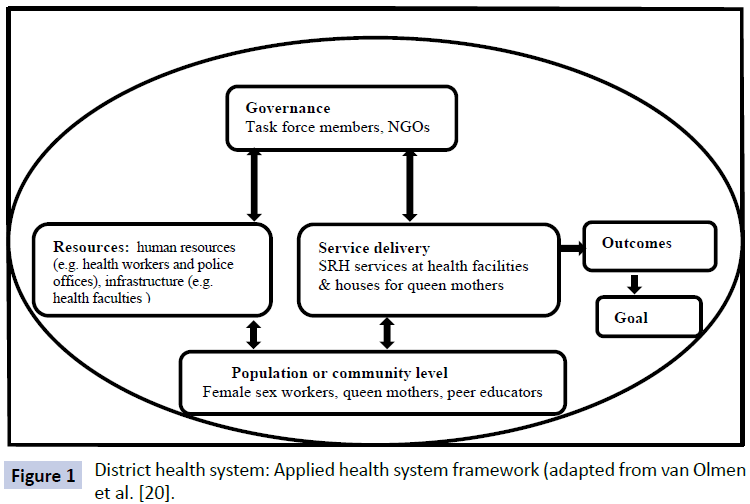

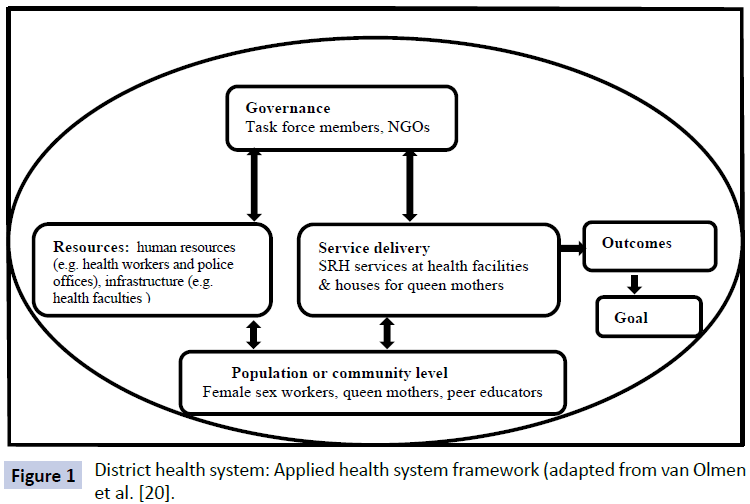

The health system in Zambia consists of formal and informal sectors. The formal health sector, which is the main provider of health care services, is made up of different service providers, namely state-owned health facilities, faith-based health facilities and the private sector [19]. This paper adopts the definition of health system by van Olmen et al. [20], which conceive the health system as consisting of governance and leadership, resources, service delivery, population, outcomes, and goals functions. Figure 1 shows the district health system functions in Zambia.

Figure 1: District health system: Applied health system framework (adapted from van Olmen et al. [20].

Meanwhile, there is limited knowledge on the factors that shape the acceptability and adoption of strategies aimed at improving access to SRH services for FSWs into health systems. Most of the studies on acceptability of SRH strategies have focused on children and adolescents living in institutionalised care [21]; mechanisms that trigger the transformation of ‘ordinary’ SRH health care facility into adolescent-friendly health services (for all categories of adolescents) [22]; as well as accessibility to SRH by young people living with HIV [7,8,23]. This study aimed at addressing the knowledge gap by analysing the factors that shaped the acceptability and adoption of the Emerging Voices project for addressing the SRH needs for FSWs into the health system at district level in Zambia.

Methods

Study design

This was a qualitative study which used a case study design in collecting data. The case study methodology is an empirical approach that investigates contemporary phenomena within a real-life context, where the boundaries between phenomena and context are not clearly evident and in which multiple sources of evidence such as in-depth interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs) and review of documents are used [2,24]. This was a case study of the integration process of the Emerging Voices project –a project aimed at delivering SRH services to FSWs- into the health system at district level. Data were collected in December 2013, one year after the project had been implemented.

The project was introduced in Chipata district by the Alliance Zambia a country-level partner of the International HIV/AIDS Alliance. The project was later handed over to the Southern African AIDS Trust (SAT) Zambia. The purpose of the project was to promote HIV prevention by increasing access to and uptake of integrated SRH health services by FSWs aged 18–24 in Chipata district. The project commenced 2012 with a baseline assessment of the health-related issues facing FSWs in the district. Findings from the assessment guided the design and implementation of project. The assessment showed that FSWs faced several problems such as physical violence and forced sex at the hands of police officers and stigmatization from health worker which hindered their access to SRH services. The project was implemented two NGOs: Young, Happy, Healthy and Safe (YHHS) and Chisomo Community Programme. The three broad areas of activity for the project were conducting outreach activities to FSWs; referring FSWs to services; and linking stakeholders to each other.

Study setting

Chipata, the study district, is the administrative center of Zambia’s Eastern Province. Chipata District has a population of about 450,000 [13]. The city of Chipata is less than 20 kilometers from Zambia’s border with Malawi. The main road connecting the Zambian capital of Lusaka to the Malawian capital of Lilongwe runs through Chipata, making it a hub of activity for long-distance truck drivers. Their presence in Chipata is thought to be one of the factors shaping the city’s commercial sex industry. No surveys have been conducted to assess the number of female sex workers in Chipata. In Chipata district, the situation assessment on HIV and sex workers conducted in 2012 showed that that they are approximately 600 FSWs.

Data collection

Data collection was done using in-depth interviews, FGDs, observations and review of documents. Guides were used in conducting the interviews and FGDs. Key themes covered in the guides were type of project activities, type of information and services provided the projects, who provided the information and services, how often are these issues provided and where there are provided from. Other key themes were the quality, relevance, utilisation and limitations of the information and services as well as recommendations for improving the project implementation process.

In-depth interviews

Following an initial desk review, most other data collection activities took place during a five-day visit to Chipata. In-depth interviews were conducted with peer educators, queen mothers, Task Force members and staff members at the implementing NGOs. Two FSWs participated in-depth interviews: one, a task force member, and the other, a project beneficiary. In-depth interviews were also conducted with SAT/Zambia staff members. On average, each interview lasted between 45 minutes and an hour.

Focus group discussion

Three FGDs were also conducted. One brought together six FSW participants who were primarily beneficiaries of Chisomo activities, and another with five FSW participants who were primarily beneficiaries of YHHS activities. These two focus groups were asked about their experiences and opinions in relation to the project. At the third focus group discussion, five Task Force members participated in a written exercise and discussed the insights that arose from the exercise regarding the task force’s performance. Overage, the FGDs lasted between one and half hours to two hours.

Observations

We also visited the houses of the queen mothers in order to understand how the information hubs looked like. Three houses for queen mothers were visited. The other reason for undertaking the observations was to understand the type of services provided in the houses and also conduct informal discussions with some of FSWs that were living in these houses to assess the acceptability and adoption of the SRH services.

Review of documents

Additional data came from project documentation provided by the implementing partners. Documentary review was conducted in order to get in-depth insight on the project outcomes and inputs and how far these had been achieved.

Data analysis

All interviews were recorded digitally and later transcribed verbatim by the first author. When data collection was complete, each author analyzed the data individually to identify key project activities, results, challenges and lessons from the findings. The authors then synthesized these preliminary findings into common themes. We followed a thematic analysis approach, which “is a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organizes and describes a dataset in (rich) detail and goes further to interpret various aspects of the research topic” [25].

During the analysis, a code manual was inductively developed. The process of developing of this code manual was based on the key questions and the theoretical underpinnings of the diffusion of innovations theory [26]. To facilitate credibility of data analysis process, the code manual was then separately reviewed by all authors. The process of reviewing the code manual involved systematically comparing it to the dataset that was collected during the fieldwork in order to arrive at the final code manual. Finally, the data from the in-depth interviews were then triangulated with the information gathered through FGDs, and the document review [27]. The process of triangulation involved checking for the differences and similarities in the content of the data. The process of analysing data was an iterative analytical process which involved moving back and forth between data sources, codes and themes [18,27].

Ethical issues

We obtained informed consent from all the study participants before conducting in-depth interviews and FGDs. Further, we also explained in detailed the research objectives to the study participants before they could be interviewed. In addition, the study participants were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any point. We also assured the study participants that confidentiality was going to be observed during and after study. During the data analysis and writing process, the respondents’ personal details were withheld so that it is not possible for readers to attribute views or statements to specific individuals.

Results

This section presents the findings of the assessment of the process of integrating an innovative project for increasing access to SRH services by FSWs, the Emerging Voices project, into the health system at district level. The findings have been organized into two broad topics: relative advantage of the project and compatibility of the project with health system functions.

Relative advantage of the Emerging Voices project and integration process

One of the key factors which facilitated the integration of the Emerging Voices project into the health was that the project was perceived as advantageous compared to existing SRH strategies. Unlike other strategies, especially those managed by the government, the project used a local multisectoral team in the project implementation process.

Involving a local multisectoral team in project implementation

Compared to existing SRH projects which are provided by mainly the government, the Emerging Voices was unique because it used a Task Force to coordinate the project implementation and monitoring processes. This Taskforce comprised different organizations and institutions. It had representatives from FSWs, health workers, the police, NGOs and religious leaders. The FSW representative was selected from a community based organisation which focused on promoting the rights of FSWs in the district. Her role was to bring forward to the Task Force the challenges that FSWs faced and participate in developing solutions to the challenges. Involvement of such a diverse local team facilitated development of strategies that were locally relevant. Furthermore, this team approach helped the stakeholders appreciate the challenges that FSWs were experiencing and the importance of prioritising the SRH needs of FSWs.

“The Emerging Voices has challenged the widespread stigmatisation of female sex workers by giving us insight into the obstacles facing these women. Most of us Task Force members are in leadership roles in our organisations and government departments and our participation in this project has helped us learn the difficulties that FSWs face and also to respect FSWs as valuable members of the community and as people who are equally deserving of their human rights.” (Task Force member 1, FGD).

Involvement of different stakeholders helped the Task Force members to learn from each other and draw on each other’s strengthens in meeting the SRH needs for FSWs. The possibility of learning from each other and networking improved service delivery to FSWs by strengthening referral processes.

“We are also able refer some FSWs within network for all member organisations that are represented in the Task Force. For example, if my organisation does not provide HIV testing, I refer the person to another organisation in the Task Force which conducts HIV testing. This kind of networking has increased acceptability and utilization of the services by FSWs” (Task Force Member 3, FGD).

The project also triggered change of attitude among other essential workers or staff such as the police and health workers who were not part of the Task Force. This change in attitude was a result of the advocacy on the need of paying attention to the situation of FSWs which was done by the Task Force members in their various institutions and organisations.

Regarding the police, several FSWs gave personal examples of how the manner in which police officers treated them had changed since the implementation of the project. Problems which FSWs encountered with the police before the project such as police officers allegedly demanding money sex from FSWs in exchange for not arresting them for loitering in the night reduced. It was also reported that some police officers helped FSWs claim their fees from clients who engage their services but then do not want to pay.

“I had a client who refused to pay me after sex. With the help of my friends we took him to the police. They forced him to pay” (FSW 6, FGD 2).

Similarly for health workers, it was reported that segregation, stigma, discrimination and sometimes even the denial of basic health services such family palming had reduced in clinics and health centres in areas covered by the project. A story from one informant vividly demonstrated the potentially fatal consequences of refusal to provide services to FSWs such treatment for STIs before the project was implemented.

“My friend [a fellow FSW] went to hospital after suspecting that she had an STI. The health worker told her that she would only attend to her after bringing the partner. She could not manage to bring the partner. She went there two more times, but the health worker declined. The situation became worse and she died” (FSW 2, IDI).

Evidence from FSW suggested that health workers were now treating FSWs in a friendly manner. This situation had encouraged FSWs to access treatment for STIs and HIV and other SRH services such as contraceptives. Involvement of health workers in community meetings also helped them change their attitude. The statement below provides an example of this change of attitude by health workers towards FSWs.

“I had STIs at three different times. Each time I went to the health facility I was turned back and told to bring a boyfriend. But this this time, I got a referral letter from a peer educator and I was well received and attended to by a nurse” (FSW 6, FGD1).

Project compatibility with district health system and integration process

Compatibility refers to how well the innovation, in this case the project, is attuned to values, health care expectations and practices within the health system. Key issues which facilitated programme compatibility were the use of queen mother’s houses as information hubs and condom distribution centres as well as the involvement of queen mothers, FSWs and peer educators in referring FSWs to health facilities.

Use of queen mother’s houses as information hubs and condom distribution centres

Many FSWs indicated that the use of queen mother’s houses as information hubs and service provision centers facilitated their acceptability of SRH services as this approach was compatible with the with their expectations of what good SRH services should be. Queen mothers are older and retired FSWs who provide accommodation to younger FSWs and FSWs pay to queen mothers a percentage of their earnings. FSWs reported that acquiring condoms and information from queen mothers was good as these service points can be easily located and accessed by FSWs. In addition accessing condoms from queen mothers was less stigmatising than accessing them from other sources. Furthermore, the ready availability of condoms at queen mother’s houses was important for some FSWs who were reluctant to keep large supplies of condoms in their homes because they do not want their children or stable boyfriends to know that they were involved in sex work.

The other advantage of using queen mother’s places was that FSWs were able to access several services at one point. They informed that when they go to access condoms at the queens mother’s places, there were also able to access information on other family planning methods, cervical cancer screening services and also HIV testing and treatment. This approach was much more preferred than other SRH strategies for example placing condoms in the bars as FSWs were not able to get vital information from such sources.

“Because we are able to provide different services at one point in the community, we have been to refer FSWs when they come to collect condoms to different services such as HIV testing and cervical cancer screening. This initiative is working better than the other SRH strategies that we have participated in. For example, in less than a year, 234 FSW know their HIV status and 254 have been referred to various health services” (Staff Chisomo).

Involvement of queen mothers FSWs and peer educators in referring FSWs to health facilities

Review of data further showed that as FSWs access information at the hubs, queen mothers also refer them for HIV, STI, family planning and cervical cancer services. This was done through giving information about the service points, giving FSWs referral letters or escorting them to institutions which provide services. FSWs assumed another important role of escorting friends to health facilities after the FSWs had been referred by project representatives or peer educators. In addition, some FSWs reported providing support to friends who were admitted to health facilities, for example by helping them meet their basic needs and or encouraging them take treatment.

The inclusion of peer educators in providing SRH services to FSWs proved very effective and locally acceptable, as peer educators were selected with the help of community leaders. To be selected as a peer educator, one should have had experience in working with FSWs. The project had 18 peer educators: Ten peer educators managed by Chisomo underwent training in February 2013, and eight peer educators managed by YHHS underwent training in March 2013. The training was on health promotion strategies. In addition to conducting referrals, peer educators also carried out door-to-door outreach and sometimes made presentations at community outreach meetings on SRH issues. Peer educators also distributed condoms on an ongoing basis and carried out night watch order to recruit more FSWs in the project. Condoms were also placed in the bars.

Referral processes and support provided by queen mothers, FSWs and peer educators enhanced FSWs accessibility and adoption of SRH services as FSWs were attended to quickly when they had a referral letter. Good referral processes also facilitated increased disclosure of HIV status to peer educators and queen mothers, which in turn fostered social support and treatment adherence support. Whereas being escorted by someone to the health facility was important as it reduced social stigmatization.

“Many FSWs are now able to seek services because we are being escorted by our friends or peer educators. Being escorted is good because these peer educators are known at the hospital…… so when you go with them you are quickly attended to. Having someone also by your side reduces stigmatisation” (FSW 5, FGD 1).

It was reported that this increased access to services helped improve the health status of the FSWs. Seeing other FSWs improve after being put on HIV treatment appeared to be a motivation for FSWs to seek treatment. Being in good health generally helped reduce HIV stigma.

“My friend who is HIV-positive became very sick. She also had STIs. We took her the hospital. She was put on treatment and she is looking attractive. She even manages to have about five men per night” (FSW 2, FGD 2).

Although the project recorded some progress with regard to integration, there were some limitations. Implementing partners did not only find FSWs to be highly mobile, but also encountered cases in which FSWs may have lied about where they lived because they were in Zambia illegally. Study informants also speculated that some FSWs who live in more rural areas could not afford to travel to communities where the project is being implemented. There were concerns about continuity of project activities in case of queen mothers relocating to other areas or queen mothers failing to pay house rentals. It was proposed that it was important to find a permanent site in the community for conducting the activities. However, the project did not include any provisions for the funding of permanent project sites in the community. Limited confidentiality in some health facilities also discouraged some FSWs from accessing the SRH services.

Discussion

This paper has reviewed the factors that shaped integration process of the Emerging Voices project into the health system at district level in Zambia. Factors that facilitated the integration process included the perceived relative advantage of the project over other existing SRH strategies. The inclusion of the Task Force consisting of different stakeholders made the project to be perceived as more advantageous than other existing SRH strategies. The Task Force facilitated integration of the project into the service delivery health systems function in the district. This integration was possible because the members of Task Force were in senior positions thereby easily advocating for increased attention towards the needs of FSWs within their respective organisations and institutions which included health facilities and the police. Key positive outcomes of this advocacy included some health workers developing a positive attitude towards FSWs and improved referral system for SRH services for FSWs. Good communication processes helped overcome tension among relevant stakeholders

In addition, the use of structures at community level such as queen mother’s houses to deliver SRH services to FSWs facilitated the compatibility of the project with the health system functions such as the population or community and health service delivery. This was possible because use of queen mothers was in line with FSWs’ expectations of what friendly SRH friendly services should be like; since offering services at such points reduced stigmatization and distances to SRH service points. The of issue of compatibility of new innovations with prevailing practices, expectations, values and norms with the health system elements is important because compatibility reduces possible conflicts which can either delay or distort the integration process [18]. In addition, compatibility further strengthens the pattern and rate of integration by providing the innovation with a clear advantage over the existing similar strategies [26,28,29].

The use of the Task Force and queen mothers in the project in general facilitated the integration process by enhancing the FSW’s confidence into the services provided by the project. Further, involvement of the community structures such queen mothers and also peer educators facilitated the community’s sense of programme ownership. Whereas community participation and involvement of stakeholders from the government and NGO sector through the Task Force facilitated the integration process by triggering the perceived legitimacy, credibility and relevance of project among FSWs. Some of these attributes are similar to study conducted in Latin America among adolescents who showed for that self-confidence by local stakeholders in SRH services as well as the perceived legitimacy and relevance of the SRH services by the adolescents positively facilitated the uptake of the services [22].

The analysis of the integration of the Emerging Voices project into the health system shows that what happens in one health system function may have an effect in another function. For example the integration of activities within the resources health systems function through advocacy activities among health workers by the Task Force representative facilitated integration into the health service delivery and population functions of health system. This integration took the form of change of service delivery towards making the services more friendly thereby triggering increased acceptability of the services by the members of population or community. This scenario effectively illustrates the interconnectedness of the different levels of the health system, insofar as what happens at the meso level (district level or organisation level) has ripple effects that affect other elements on the micro level or community or population level [30].

Effectively providing services to FSWs or replicating the project to other areas in the country requires formalising service points which are compatible with FSWs such as use of queen mother’s house in SRH service provision. Furthermore, it is also important engage a Task Force comprising key stakeholders in given context and formalise its role in project implementation process through providing a budget specifically for the Task Force. Formalisation has also the potential of strengthening service provision and addressing the challenges with regard to providing SRH to FSWs which include FSWs being highly mobile, limited accessibility to services by FSWs in rural areas as well as concerns about how to sustain the use of queen mother’s houses and the Task Force in SRH service provision.

Trustworthiness

We aimed to enhance the trustworthiness of the study by attending to aspects of credibility, dependability and transferability of our study findings [18,31,32]. Some of the way through which attempted to strengthen the credibility and dependability of findings was through individually systematically reviewing the data and inductively coding and categorization [33]. We also shared and discussed the codes and categories in order to arrive at the final themes of the findings. The process discussing the data enabled us gain deep insights of the data. With regard to transferability by of the findings, we attempted to achieve this through providing a rich description of the study subject, data collection and analysis process. In addition, the inclusion of quotations in the text representing a variety of study informants also enhanced transferability of findings [34].

However, not including other health workers in the study who are not part of the Task Force denied the study additional insights on the relationship between FSWs and health workers. However, by systematically highlighting context-specific processes of integrating the Emerging Voices in the health system, this work may provide a basis for analytic generalizations that could provide useful insights not only to the implementing NGOs but also to organisations, institutions policy makers in Zambia and other low and middle income countries. As a follow up, we recommend conducting a mixed methods study with a larger sample of FSWs, health workers, staff from the NGOs and police in order to ascertain the impact of the project on accessibility to SRH by FSWs and also health outcomes.

Conclusion

Factors that facilitated the integration process of the Emerging Voices project into the health system included the relative advantage of this innovation compared to existing SRH strategies as this project had more comprehensive services and broader stakeholder involvement. Furthermore, the compatibility of the initiative with health care expectations of FSWs through the use of community structures such as queen mothers’ houses in delivering SRH services positively facilitated acceptability and adoption of the services by the FSWs. The referral forms and systems developed for this project, and used by the queen mothers and peer educators could easily become permanent features of the service provision network for an SRH project targeting FSWs. Formal and informal capacity-building activities that targeted peer educators and queen mothers may encourage these community members to maintain their roles as health educators and advocates for the rights of FSWs which are essential for project sustainability. More generally, FSWs who have been empowered by their experiences with the Emerging Voices project may now insist on higher standards of conduct for clients, police officers and health care providers. Finally, the relationships forged between FSWs and representatives of powerful institutions such as the police service and district government offices may facilitate continuing collaboration beyond the life of the Emerging Voices project.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed towards the study design, read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

International HIV/AIDS Alliance African Regional Programme, Southern African AIDS Trust Zambia, Young, Happy, Healthy and Safe and Chisomo Community Programme for making the study process possible. We are also indebted to all the study participants for participating in the study.

6638

References

- Greifinger R, Dick B (2008) A qualitative review of psychosocial support interventions for young people living with HIV.

- Zulu JM, Kinsman J, Michelo C, Hurtig A-K (2013) Developing the national community health assistant strategy in Zambia: a policy analysis. Health Res Policy Syst11(24): 1186.

- Denison JA, McCauley AP, Dunnett-Dagg WA, Lungu N, Sweat MD (2008) The HIV testing experiences of adolescents in Ndola, Zambia: do families and friends matter? AIDS care20(1):101-105.

- MacPhail CL, Pettifor A, Coates T, Rees H (2008) “You must do the test to know your status”: Attitudes to HIV voluntary counseling and testing for adolescents among South African youth and parents. Health Education & Behavior35(1):87-104.

- Onifade I (1999) Unmet reproductive health needs of adolescents: implications for HIV/AIDS prevention in Africa. The Continuing HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Africa.63-72.

- Ayres JRdCM, Paiva V, França Jr I, Gravato N, Lacerda R, et al. (2006) Vulnerability, human rights, and comprehensive health care needs of young people living with HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health96(6):1001.

- Birungi H, Mugisha JF, Obare F, Nyombi JK (2009) Sexual behavior and desires among adolescents perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus in Uganda: implications for programming. Journal of Adolescent Health44(2):184-187.

- Moore L, Chersich MF, Steen R, Reza-Paul S, Dhana A, et al. (2014) Community empowerment and involvement of female sex workers in targeted sexual and reproductive health interventions in Africa: a systematic review. Globalization and health10(1):47.

- World Health O (2011) Preventing HIV among sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review.

- Richter M, Yarrow J (2008) An evaluation of the RHRU sex worker project–an internal report.Johannesburg, Reproductive Health and HIV Research Unit.

- Central Statistical Office of Z (2011) Zambia 2010 Census of Population and Housing. Preliminary Population Figures. In.: CSO Lusaka, Zambia.

- al Me: Zambia HIV Prevention Response And Modes Of Transmission Analysis. In. Lusaka 2009.

- Atun R (2012) Health systems, systems thinking and innovation. Health policy and planning27(suppl 4):iv4-iv8.

- Cutler DM, McClellan M (2001) Is technological change in medicine worth it? Health affairs 20(5):11-29.

- Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, Berman P, Boerma T, et al. (2010) Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. The Lancet375(9730):2032-2044.

- Zulu JM, Hurtig A-K, Kinsman J, Michelo C (2015) Innovation in health service delivery: integrating community health assistants into the health system at district level in Zambia. BMC health services research15(1):38.

- Mumba Zulu J (2015) Integration of national community-based health worker programmes in health systems: Lessons learned from Zambia and other low and middle income countries.

- Olmen VJCB, Van Damme W, Marchal B, Van Belle S, Van Dormael M, et al. (2010)Analysing health systems to make them stronger. In. Antwerp.

- Abadía-Barrero CE, LaRusso MD (2006) The disclosure model versus a developmental illness experience model for children and adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in Sao Paulo, Brazil. AIDS Patient Care & STDs20(1):36-43.

- Goicolea I, Coe A-B, Hurtig A-K, San Sebastian M (2012) Mechanisms for achieving adolescent-friendly services in Ecuador: a realist evaluation approach. Global health action5.

- Bakeera-Kitaka S, Nabukeera-Barungi N, Nöstlinger C, Addy K, Colebunders R (2008) Sexual risk reduction needs of adolescents living with HIV in a clinical care setting. AIDS care20(4):426-433.

- Yin RK (1994) Case study research: design and methods. Thousands Oaks. International Educational and Professional Publisher.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 3(2):77-101.

- Zulu JM, Michelo C, Msoni C, Hurtig A-K, Byskov J, eta l. (2014) Increased fairness in priority setting processes within the health sector: the case of Kapiri-Mposhi District, Zambia. BMC health services research 14(1):75.

- Scott SD, Plotnikoff RC, Karunamuni N, Bize R, Rodgers W (2008) Factors influencing the adoption of an innovation: An examination of the uptake of the Canadian Heart Health Kit (HHK). Implementation Science 3(1):41.

- Nanyonjo A, Nakirunda M, Makumbi F, Tomson G, Källander K (2012) Community acceptability and adoption of integrated community case management in Uganda. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 87(5 Suppl):97-104.

- Bocoum FY, Kouanda S, Kouyaté B, Hounton S, Adam T (2013) Exploring the effects of task shifting for HIV through a systems thinking lens: the case of Burkina Faso. BMC public health 13(1):997.

- Edvardsson K, Ivarsson A, Eurenius E, Garvare R, Nyström ME, et al. (2011) Giving offspring a healthy start: parents' experiences of health promotion and lifestyle change during pregnancy and early parenthood. BMC public health11(1):936.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today24(2):105-112.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research 15(9):1277-1288.

- Patton MQ (1999) Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health services research 34(5 Pt 2):1189.