Research Article - (2022) Volume 16, Issue 10

Interactions between Cetaceans and Small-Scale Fisheries around the Central Mediterranean Maltese Islands

1Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture, University of Heriot- Watt Għammieri, Ingiered Road, Marsa, MRS 3303, Malta

2Department of Agriculture, Aquatics and Animal Sciences, Institute of Applied Sciences, Malta College for Arts, Science & Technology, Luqa Road, Qormi, Malta

*Correspondence:

Matthew Laspina, Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture,

University of Heriot- Watt Għammieri, Ingiered Road, Marsa, MRS 3303,

Malta,

Tel: 35699807567,

Email:

Received: 18-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. IPFS-22-11440;

, Pre QC No. IPFS-22-11440(PQ);

Reviewed: 07-Mar-2022, QC No. IPFS-22-11440;

Revised: 11-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. IPFS-22-11440(R);

Published:

18-Mar-2022, DOI: 10.36648/1307-234X.22.16.104

Abstract

Cetacean depredation poses threats to both the socioeconomic

viability of fisheries as well as species

conservation. This study is based in the Maltese Islands

where the fishing sector has always been one of a smallscale

nature with 93% of the vessels being less than 12

meters in length. Maltese fishers engage in small-scale

fishing utilizing a variety of artisanal fishing gear including

surface long lines, which are mainly used to target swordfish

and tuna and bottom-long lines; trammel nets and

entangling nets which are used to target groupers, various

species of bream, red snappers and red porgies; and pots

and traps which are generally used to captured octopus and

bogue. This study, which aimed to analyze fishers’

perception with respect to interaction occurrence between

small-scale fisheries and cetaceans in Maltese waters, found

that fishers claim that dolphin presence has increased in the

past five years, particularly in the vicinity of Bluefin tuna, sea

bream and sea bass fish farms locations. While the use of

trammel nets remains by far the most popular gear type

employed by Maltese fishers, this study showed that around

33% of the fishing gear deployed in the past year suffered

damages which account to an average of €178.33 in

damages per fisher, annually. It is therefore essential that

proper monitoring is carried out in order to assess the

factors that drive the interactions and the impact of dolphin

depredation on the fishing sector.

New prevention and mitigation measures are proposed in

order to try and reduce the risk of depredation by cetaceans

in Maltese waters. This study provided first-hand insights

which will aid in the execution of local fisheries

management plans and subsequently, ecosystem-based

fisheries management.

Keywords

Cetaceans; Small-scalefisheries; macrocephalus;

Common bottlenose dolphin; Depredation; Maltese Islands

Introduction

Dolphins exhibit foraging plasticity and utilize various foraging strategies to cover their cost of living [1]. They have also learned to exploit anthropogenic activities and especially fishing activities, by consuming from nets and discards at a low energy cost [2]. As a result, in the Mediterranean Sea, dolphin-fisheries interactions are considered to be persisting issue, with socioeconomic and ethical implications that further complicate fisheries management [3-4]. They are of major concern since they reportedly result in gear damage, increasing the cost of coastal fishing on a regional and global level [5].

This study delves into cetacean depredation, which is, the act of these large marine predators feeding on fisheries catches, a phenomenon that poses threats to both the socio-economic viability of fisheries and species conservation, stressing the need for mitigation [6]. The complex interrelationships between marine mega fauna and human impacts on the marine ecosystem make simultaneously managing the use of marine resources and protection of these species especially challenging [7]. However, fisher experience and knowledge is an important source of information for the study of fisheries complexity and should be taken into account during the design of fisheries management strategies [8].

This study is based on fishers who operate in Maltese waters. Found in the central Mediterranean, the Maltese islands lie c.80 km south of Sicily. Considered as being surrounded by warm waters, sea water temperatures reach an average of 14°C between December and February and 28°C in the summer months. The fishing sector in Malta has always been one of a small-scale nature with a long history of fishers engaging in traditional small-scale fishing practices. However, its cultural significance outweighs the economic importance which is equivalent to about 0.1 percent of the national gross domestic Product.

The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund defines Small Scale Fisheries as “Fishing carried out by fishing vessels of an overall length of less than 12 m and not using towed fishing gear” (EC) No 26/2004. Therefore, for the purpose of this study any vessel of overall length less than 12 m, operating in Malta’s 12 Nautical Mile zone (a Fisheries Management Zone as per EC 1967/2006), and not using towed fishing gear was considered “small-scale”. Most of the industry in Malta is composed of small-scale vessels. This small-scale fishing fleet has been noted to be facing degeneration such that Malta faced a decline of 30% in the number of vessels, ranking among the top EU countries experiencing such degeneration. Currently, the smallscale fishing fleet is composed of 916 fishing vessels, 41% of which are full-time registered vessels while 59% are part-time fishing vessels.

Of the 87 living cetacean species found in the world’s oceans and seas, around eight species are considered to be residents of the Mediterranean Sea. Several naturalists have noted cetacean presence in Maltese waters, specifically the common bottlenose dolphins; however other species of cetaceans have been recorded in the seas around Malta. These include sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), Cuvier’s whale (Ziphius cavirostris), Sowerby’s whale (Mesoplodon bidens), the bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), the striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba), spotted dolphin (Stenella frontalis), rough toothed dolphin (Steno bredanesis) and many others (Savona-Ventura, n.d.). Fin whales have also been sighted in Maltese seas. Further mentioned the minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), the killer whale (Orcinus orca) possibly sighted off Malta years ago and the false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) also found rarely throughout the Mediterranean basin, and in particularly in Sicily and of Malta itself). In the recent past, there were a number of cetacean sightings, the latter identified as bottlenose dolphin (38%), striped dolphin (30%), common dolphin (24%) and sperm whale (2%). The most popularly occurring cetacean remains Tursiops truncates which has been appearing the Maltese waters for a number of years [9].

The realities occurring in different countries have been crucial to inform this study, as they provided a baseline on the type, frequency and impact of interactions. Such detail, together with the regional insights gathered from the parallel studies in Sicily and Spain, helped authors in orienting the Maltese depredation inquiry.

With an ever-increasing need to study dolphin population ecology coming from national/international directives, support from citizens to aid research may act as a practical, inexpensive solution to gathering extensive spatial–temporal data for regional-scale monitoring and for the development of management priorities.

This study is based on three research questions, namely;

• What is the fishers’ perception of dolphin depredation in Maltese waters?

• What is the frequency of cetacean-fisheries interactions in Maltese waters?

• What is the impact of cetacean-fisheries interactions in Maltese waters?

Through this analysis, the authors will be filling in a current gap of knowledge on the status of dolphin depredation in the Maltese Islands. It is for this reason that we came into contact with the local fishers, who voluntaril y shared their empiri cal knowledge, all of which were recorded in questionnaires that were carried out by native Maltese speakers. These will provide us with first-hand insights and will aid in the execution of loca l fisheries management plans and subsequently, ecosystem-based fisheries management.

Research Methodology

The research methodology was based on pre-existing protocol

outlined by the low impact fishers of E urope . The sa me

methodology was carried out by other partners and outlined

[10-11]. The same methodology was used since this study is

being carried out in Spain, Sicily and Malta under the auspices of

the low impact fishers ofE urope and funded b y the M AVA

Foundation ino rder to understand the interaction s betw een

cetaceans and small-scale fisheries through o u t the

Mediterranean Sea. The questionnaires were administer ed

through face-to-face interviews with fishers in differen t por ts

around Malta, using convenience sampling. A total of 38

questionnaires (33 of which were used for a nalytical purpose s)

were administered over an eight-month period, namely between

July 2019 and February 2020 in six fishing ports. These include

St. Paul’s Bay, Marsaxlokk, Cirkewwa, Mġarr (Gozo), Marsaskala,

Ġnejna, Msida and Mellieħa.

The questionnaires were carried to assess the opinion of fulltime

and part-time fishers, all of which were men. A wide

spectrum of data on the SSF in Malta was collected. This

included data on the port at which the vessel is berthed, the GT

tonnage of the vessels, the Length over All (LOA) of the vessel,

the engine power (kW) and the year of construction of the

fishing vessels. The fishing gears utilized by both full-time fishers

and part-time fishers were recorded in codes as per Table 1 (Annex).

| Fishing gear code |

Common name of fishing gear |

Demersal/Pelagic/Both |

| GTR |

Trammel Nets |

Demersal |

| GTN |

Combined Gillnets-trammel nets |

Both |

| GNS |

Set Gillnets |

Demersal |

| FPO |

Pots |

Demersal |

| LLS |

Set Longlines |

Demersal |

| LTL |

Troll lines |

Pelagic |

| LLD |

Drifting longlines |

Pelagic |

| LHP |

Handlines and pole-lines (Hand-operated) |

Both |

| LHM |

Handlines and pole-lines (mechanized) |

Both |

| GND |

Drifting gillnets |

Pelagic |

| PS |

Purse-seines |

Pelagic |

| LA |

Lampara nets |

Pelagic |

Table 1: A list of fishing codes recorded in the 8 fishing ports where the questionnaire data was collected from.

Data was also gathered on the characteristics of the fishing

gear used. The type of gear used by the fishers was outlined and

information on the fishing gear characteristics w a s collect ed.

This included information on the material utilized such as nylon

and monofilament, the mesh size of the fishing nets and t he

number and sizes of hooks utilised, the length and height of the

gear and the days and times spent at sea. The cost of fishing

gear was also collected.

The cetacean interactions were investigated by enquiring

about the frequency of the encounters over the past five years

including whether any incidental catch had been caught during

these interactions. The fishers were also asked whether they

have ever heard of any mitigation measures with regards to

warding off cetaceans, whether they would benefit from this

mitigation and whether they would be willing to participate in an

online voluntary survey to inform on the locations at which

they encountered cetaceans, for further research.

The frequency of encounters was also recorded and what

species depredated the gear suffered was also noted. The

questionnaire also identified which gear was mostly affected and

which species are generally targeted using that type of gear. The

type of incidental catch captured, and the frequency of

incidental catch was also noted mainly focusing on what

incidental catch species was captured such as dolphins, whales,

sharks, turtles, birds or any others.

Further analysis was carried out to show which type of fishing

gear encountered any interactions with dolphins and at which

fishing areas these interactions occurred. The questionnaire was

also used to collect data on the period of time, the number of

hours at which these fishing activities were carried out and a t

what depth and distance these fishing activities occur, as well as

the cetacean interactions encountered. The questionnaire w as

also used to obtain an idea of the target species that are

captured with this gear, in order to understand what fishers

were fishing for when they encountered the cetaceans.

Information on whether the interactions with cetaceans were

positive, indifferent or negative was also recorded. The

percentage of the negative interaction and the type of damage the fishing gear may have undergone due to a negative

interaction was documented. This was classified through a

typology of the interaction on the fishing catch such as the

depredation of catch, scattering of prey, depredation of lures,

holes (including the size of the holes), bite marks found on the

catch or whether the cetacean only leaves the fish head. This

questionnaire was also used to analyze the percentage of the

reduction of the catch and whether the catch was completely

lost due to the cetacean interaction, along with costs incurred

from a negative interaction and the percentage of the gear that

was damaged during the negative cetacean interaction.

Results and Analysis

The results attained brought forward several characteristics related to the to the depredation phenemenon in SSF and enabled the researchers to understand which fisheries are mostly affected and how these interplay with the fisheries sector’s socio-ecological resilience. The results showed that the fishing gear utilized by the respondents are mainly passive gear which included, trammel nets, gillnets, surface and bottom longlines. In term of fishing gear, trammel nets are by far the most popular gear type utilised, followed by set longlines, set gillnets and FAD purse-seines which are mainly used in the dolphinfish fishery.

The analysis of the SSF fleet characteristics of the surveyed fishers was analyzed. Of these surveyed fishers, 19 are full-time and 14 are part-time fishers. The data on the vessel characteristics indicated that the average gross tonnage of the vessels analyzed was 3.558 GT and the average LOA was 7.2 m with an average main engine power of 101.89 kW. The range of the year of vessel construction ranged from 1923 to 2018.

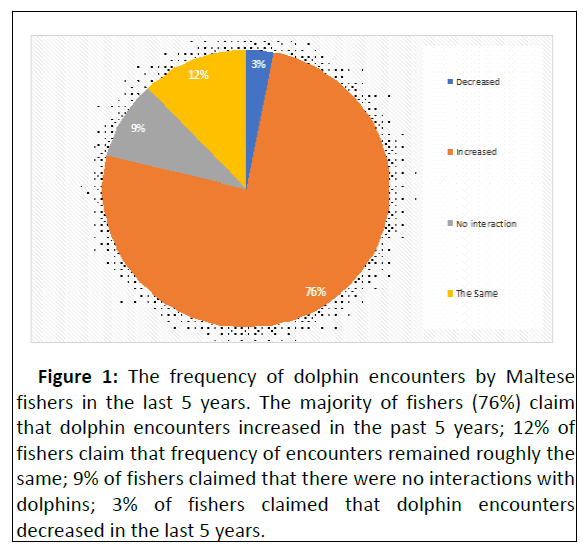

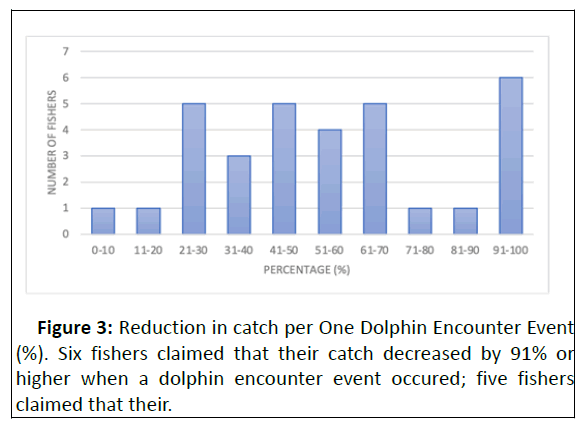

The researchers also investigated the cetacean interaction characteristics which suggested that only common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) interacted with fishing gear. Approximately, 76% of the surveyed fishers agreed that the interaction increased over the past 5 years, 76% indicated that no interaction was recorded while only 12% agreed that dolphin encounters remained the same. Only 3% of the fishers agreed that the encounter frequency decreased (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The frequency of dolphin encounters by Maltese fishers in the last 5 years. The majority of fishers (76%) claim that dolphin encounters increased in the past 5 years; 12% of fishers claim that frequency of encounters remained roughly the same; 9% of fishers claimed that there were no interactions with dolphins; 3% of fishers claimed that dolphin encounters decreased in the last 5 years.

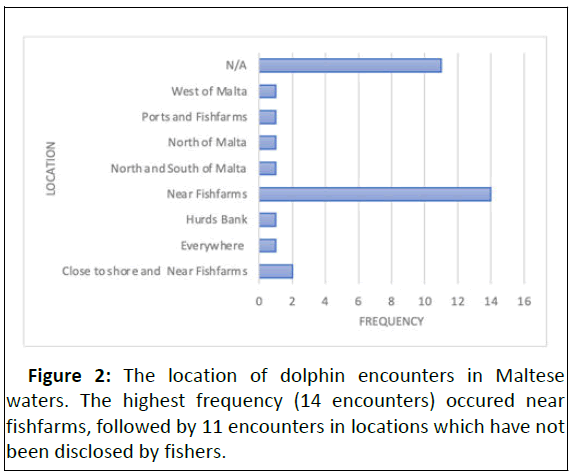

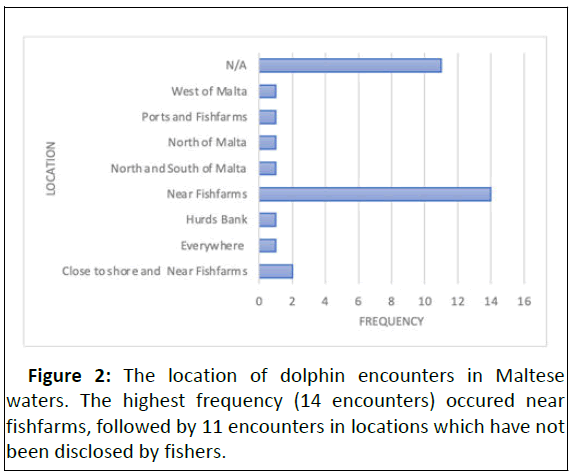

The results showed that 42% of the surveyed fishers encountered Tursiops truncates mostly in fish farm vicinities. However, 33% of the fishers did not disclose any locations, since they were concerned on revealing fishing grounds they regularly exploit (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The location of dolphin encounters in Maltese waters. The highest frequency (14 encounters) occured near fishfarms, followed by 11 encounters in locations which have not been disclosed by fishers.

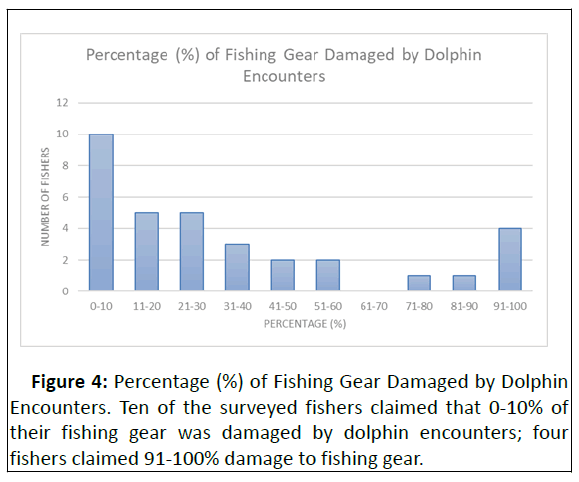

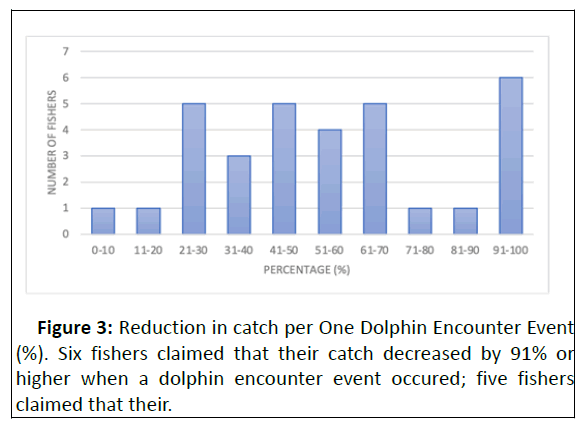

The researchers also analyzed percentage of catch that was depredated. The fishers identified that a catch was depredated due to the identification of bite marks on their catch or due to the presence of heads of fish which were depredated and captured in their gear. Some fishers complained that their catch decreases since dolphin presence tends to result in the scattering of their catch. Fishers also complained that natural and artificial lures were also depredated and nets were damaged due to the identification of holes made by the common bottlenose dolphins. The average reduction in catch sustained by fishers from one encounter is 59.22% suggesting that dolphin’s depredation does result in catch losses. The vessel owner of survey vessel 18 refrained from answering and stated that the percentage varies on every event. Six fishers stated that their catch decreases by 91% or over when dolphin pods are present, however only one fisher stated that his catch decreases by less than 10% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Reduction in catch per One Dolphin Encounter Event (%). Six fishers claimed that their catch decreased by 91% or higher when a dolphin encounter event occured; five fishers claimed that their.

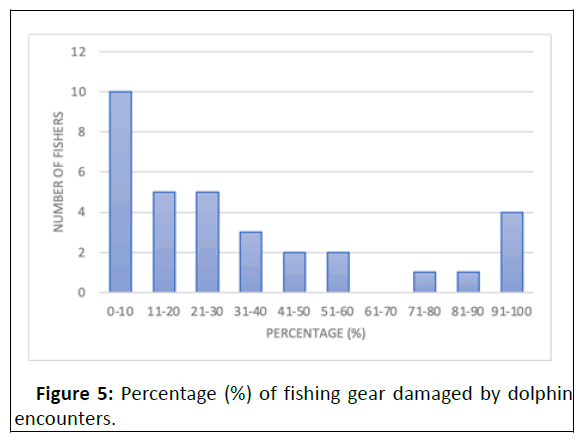

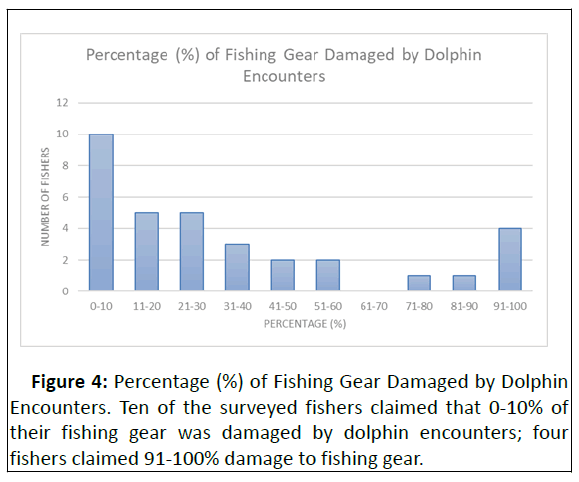

Figure 4 indicates that most of the surveyed fishers agreed that only 10% of their fishing gear was damaged. However, the results show that 33% worth of damages due to dolphin interactions. It also shows that 10 fishers seemed to agree that the percentage of their gear that was damaged between 0-10%. Only 4 fishers seemed to complain that 91-100% of their gear was damaged (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Percentage (%) of Fishing Gear Damaged by Dolphin Encounters. Ten of the surveyed fishers claimed that 0-10% of their fishing gear was damaged by dolphin encounters; four fishers claimed 91-100% damage to fishing gear.

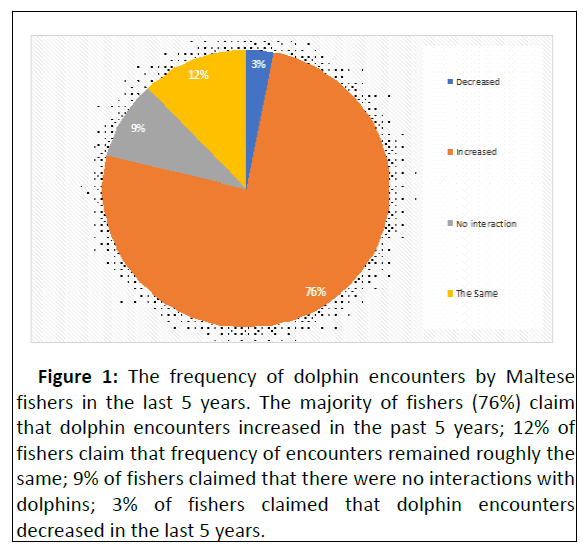

The costs incurred from the reduction in catch due to dolphin encounters was also investigated (Figure 5). Only 12 fishers answered this question since other fishers preferred not to answer. An average cost of €178.33 was calculated based on the data attained from the questionnaires. In general, costs ranged from €30 to €400. Five fishers seemed to agree that the costs incurred due to dolphin depredation was between €0-€100. Four fishers complained that the costs range from €101 to a maximum of €200. Only one fisher seemed to complain that costs range from €201 to €300 and two other fishers seemed to complain that costs range between €300 to €400.

Figure 5: Percentage (%) of fishing gear damaged by dolphin encounters.

Discussion

Depredation of fishing gear by cetaceans is considered to be of great economic concern [3]. In the last few decades due to constant technological advancements in fishing gear, depredation has attracted international attention. Depredation is defined as the “the partial or complete removal of bait or captured fish in fishing gear” by aquatic organisms such as cetaceans, fish, birds, sharks and turtles. This phenomenon is generally recorded in stationary or passive gear such as pots and traps, bottom and surface longlines, gillnets and trammels nets and other line fisheries [12]. Even though it is most commonly recorded amongst passive gears, fishers carrying out mobile fisheries such as purse-seining, trolling and trawling techniques may still experience cetacean depredation.

The results achieved in this research paper indicated that out of all the Cetacean infraorder, the common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) was the only cetacean encountered. This fits the findings reported by Debono (2020), who utilized systematic surveys to denote the regular presence of bottlenose dolphins, with 59 dolphin pod sightings with a median of 12 individuals per pod, recorded between 2013 and 2016. Debono (2020) also states that this cetacean species is widely distributed in Maltese and Gozitan waters; however they are highly common in the southern regions of the Maltese Islands. Since most of the questionnaires were carried out at Marsaxlokk, 42.1% to be exact, all the respondents questioned in this area all reported that dolphins were encountered on several fishing trips.

The pie-chart in Figure 1, shows that 75% of the fishers have stated that dolphin encounters have increased immensely over the last 5 years. A study on the dolphin interaction with gillnets fisheries in Sardinia, carried out by Diaz Lopez (2006a), and showed that out of 317 days of observation, dolphins were observed for 330.6 hours. A quantitative assessment carried out by Pulcini, et al., (2013) in the Sicily Channel. This study seemed to indicate that there was a difference in the data collected from 1998 and the data collected in 2005, since dolphin populations seemed to increase in this region. According to Panigada and Labach (2018), bottlenose dolphins are commonly in the Strait of Sicily, making Malta a highly-vulnerable spot for dolphin depredation as seen in Figure 1 (European MSP Platform, n.d.). This may be because bottlenose dolphins tend to feed on fish such as mackerel, bogue, squids anchovies and mullet which are all species that are captured in Malta.

The results shown in Figure 2 clearly demarcate that most of the Tursiops truncates encounters with fishers occur in locations close to fish-farms. This echoes finds reported by Vella (2016) who showed that common bottlenose dolphins frequently forage very close to tuna fish-farms in the South-East of Malta resulting in the depredation of fishing gear. This occurrence was also the case in the Aegean Sea coastline whereby fishers identified the main target species of the fishery and recorded the damages on gill nets and trammel nets caused by dolphins, mainly the common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) [5].

Pace et al. (2012) also stated that fish farming activities can have effect on the common bottlenose dolphins’ grouping patterns. The latter study states that food patches can model the species social structure and their behavioral repertoire which can directly affect their long-term survival. Similarly, showed that common bottlenose dolphin pods interact regularly with fish farming activities in Greece, while Lopez (2006), confirmed that dolphin activity seems to increase around fish farms due to the abundant food supply in a concentrated area. This study thus suggests that the accumulation of dolphins is a result of opportunistic feeding of mackerel which is used as bait for tuna ranching. Such a behavioral feeding strategy results in an increase in the feeding rate of dolphins and a decrease in their energy in foraging activities.

When the researchers were conducting the questionnaires and collecting data, fishers commented that trammel nets and gillnets are also taken advantage of by dolphins, since they feed on the catch captured by these fishing gears. These fishers stated that they set their fishing gears during the night and the dolphins depredate the catch early in the morning prior to the retrieval of the fishing gear. A study on the Italian artisanal fisheries carried out by Lauriano [14]. Confirm e d tha t tr ammel net and gillnets were the most vulnerable fishing gear to dolphin depredation. In fact this study showed that 72.2% of the fishing gear had been damaged by bottlenose dolphins, therefore resulting in a decrease in catch this result was also confirmed by Pardalou and Tsikliras (2020) who stated that trammel nets and gillnets that target Mullus barbatus, Mullus surmuletus and Merluccius merluccius are mostly depredated by Tursiops truncatus. The longline fishers that were questioned also stated that their swordfish longline mackerel bait is also depredated also resulting in a decrease in catch. According to Zollett and Read (2006) mackerel is the most depredated bait by dolphins.

In terms of interaction damage and losses, Table 2, provides a summary of fishing gear damage from a single dolphin encounter, describes how the commonest depredation was ‘Bite Marks’ and in most cases, respondents suffered holes in their fishing gear. Similar issues were found in Sardinia by Diaz Lopez (2006) who reported that bottlenose dolphins biting and damaging nets and forming small holes on fish-fam cages were observed. Fishers interviewed in a study carried out by Bearzi et al. (2011), stated that dolphins damaged their gear and also damaged the fish entangled in the net fatherly confirming this result. Further argue that feeding on fish from gillnets is not an inborn behaviour in the common bottlenose dolphin species, and that it is instead learned from other conspecifics. In their study, this supported by the estimated age distribution of the affected animals which were all older than 7 years.

| Fishing Gear Damage from a Single Dolphin Encounter |

|

|

|

|

| Survey Vessel |

Depredation on Catch |

Scattering Prey |

Lures Depredated |

Holes |

| 1 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

No |

- |

Yes |

| 2 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 3 |

Fish head; |

No |

- |

Yes |

| 4 |

Other |

No |

Empty Hooks |

- |

| 5 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 6 |

Other |

No |

Eat the bait off the hooks |

- |

| 7 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 8 |

Fish head; |

No |

- |

Yes |

| 9 |

Other |

No |

Empty Hooks |

- |

| 10 |

Other |

No |

Empty Hooks |

- |

| 11 |

Other |

No |

Empty Hooks |

- |

| 12 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 13 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

No |

- |

Yes |

| 14 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

No |

- |

Yes |

| 15 |

Other |

No |

Empty Hooks |

- |

| 16 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 17 |

Other |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 18 |

Other |

Yes |

Empty Hooks |

- |

| 19 |

Other |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 20 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

No |

- |

Yes |

| 21 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| 22 |

Other |

No |

Yes |

- |

| 23 |

Bite Marks |

No |

Yes |

- |

| 24 |

Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

- |

| 25 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

| 26 |

N/A |

Yes |

- |

- |

| 27 |

Bite Marks |

- |

- |

- |

| 28 |

Bite Marks |

- |

- |

- |

| 29 |

Bite Marks |

- |

- |

Yes |

| 30 |

Bite Marks; Fish head; |

Yes |

- |

- |

| 31 |

N/A |

- |

Yes |

- |

| 32 |

N/A |

Yes |

Leaves Bite |

- |

| 33 |

Bite Marks |

- |

- |

- |

Table 2: Fishing gear damage from a single dolphin encounter.

Figure 3 portrays that the average reduction in catch sustained by a fisher from one dolphin encounter event is 59.22% which implies that losses occur due to dolphin depredation. In fact, Zollet and Read (2006), confirm that dolphins engaging in depredation activities cause damage to fishing gear and decrease the value and quantity of catches. [14]. Carried out a depredation study in Sardinia and his results showed that the reduction in catch resulted in an estimated loss of €1168 per fishing vessel per fishing season. This was further confirmed by Rocklin, e t al. (2009) who reported that bottlenose dolphins attacked, on average, 12.4% of the nets and damaged 8.3% of the catch. Apart from the damage caused due to dolphin interactions, an average of 33.43% (Figure 4) of the fishing gear, worth an average of €178.33 (Figure 5) in damages was also reported. Such costs, coupled with depleting fish stocks market changes and other socio-cultural factors, are compounding the already-existing burdens on small-scale fisheries in the Mediterranean.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In this study, questionnaires were utilized to understand the

perception of dolphin depredation phenomenon and how

fishers are mostly affected by the latter in the Maltese islands.

The regular presence of bottlenose dolphins seemed to have

increased over the last 5 years, with most dolphin encounters

occurring near fish-farms. This has also been confirmed in a

study carried out by Bonizzoni et al. (2013) which showed that

bottlenose dolphins increased in the 20 km radius from fish farm

activities, due to the presence of uneaten fish feed,

accumulation of smaller prey and detritus. Trammel nets fishing

gear seemed to be the most popular gear type employed by

Maltese fishers. However, this study also showed that an

average of 33.43% of the fishing gear resulted in damages worth

an average €178.33 per year in damages was also reported. This

results in an increased pressure on artisanal fishers that is

already highly burdened by other threats (Said et al. 2018).

Although other species and external factors other than dolphins

could have been responsible for part of the damage. A study

carried out by [14]. Focusing on the Italian artisanal fishery seemed to indicate that 72.2% of the cases analyzed resulted in

damage to fish while 66.4% of the cases seemed to have gear

damage due to the cetacean interactions. This shows that this

phenomenon is a regional issue. In addition, questionnaires

carried out during this study could have been perceived by some

fishermen as an opportunity to influence future decision-making

regarding monetary compensation for the impact of

depredation and therefore, economic values cited by fishers

may be slightly inflated or erroneous overall.

Nonetheless, the reporting of cetacean depredation can be

deemed to be a decent start in analyzing the current status of

dolphin depredation in the Maltese Islands. Depredation is

generally not reported in fisheries statistics and this is

considered to be a source of mortality that is not taken into

consideration for current fish stock assessments which are

highly essential in the management of fisheries [16]. There is an

obvious need to closely monitor the depredation of gear and

amalgamate it with fisheries management and provide proper

mitigation measures [12]. It is essential that dolphin

depredation is recorded and given to STECF to provide proper

consultations to the European Commission with regards to the

proper management and conservation of marine resources [13].

The authors of this study evaluated a number of

recommendations which could be taken into consideration. First

and foremost, more studies and investigations need to be

carried out in this field. For example, the implementation of

floating laboratories, such that finds of the questionnaires are

triangulated with the on-site investigations. Who proposed that

surveys are carried out on a regular basis to determine the

cetacean interaction frequency, through continuous and ongoing

research? This would provide a more holistic picture of the

current status of dolphin depredation and its effects on the

small-scale fisheries in the Maltese Islands. Further studies on

the damage done to fishing gear should be carried out to assess

the level of depredation fishing gears undergo.

Prevention and mitigation measures can also be carried out.

For example, since acoustic devices may not be as successful

since cetaceans may get used to certain acoustic frequencies

and it may augment their capability to find fishing gear, it may be beneficial to utilise acoustic devices that emit random pulses.

that occur over a broader frequency range as suggested by

Accobams (2019). Another mitigation measure that can be utilized

to decrease interactions is the communication of cetacean

hotspots with other fishers to decrease chances of depredation as

suggested by [17-20]. Monitoring surveys at sea can also be

beneficial to assess which areas are mostly considered to be

cetacean breading and feeding grounds. The use of fishing gears

or bait with unpleasant tastes and smells could also be considered

to be an option [15,17]. Have also carried out a project known as

the “Paraped” project which was focused on constructing masking

nets in order to protect longline fishing gear. Another project

helmed by [15]. Described another measure known as the

“DEPRED” mitigation device this is a device has two main goals.

These include the startling of predators when they are in the

vicinity of the fishing gear to protect captured fish. The prototype

of the “DEPRED” device includes the eight one meter long

streamers that are constructed from tarpaulin and they are fixed

on a PVC tube of a 2 cm diameter. The upper streamers function

as a form of a deterrent to cetaceans while the lower 4 streamers

are weighted, and they cover the captured providing it a

protective effect. There are several other varieties of the

umbrella-and-stones technique; however even though

depredation prevention was successful this prototype had a

detrimental effect on the catches. Ultimately cetacean presence

in Maltese waters could be exploited for the local coastal

economy, which includes activities such as dolphin watching,

merchandising, and fishing tourism, as a diversification activity for

fishers [26-30].

References

- Nowacek DP (2002) Sequential foraging behaviour of bottle-nose dolphins Tursiops truncates in Sarasota Bay. Florida Behav Health 139:1125−1145

[Google Scholor]

- Rocklin D, Santoni MC, Culioli JM, Tomasini JA, Pelletier D, et al. (2009) Changes in the Catch Composition ofArtisanal Fisheries Attributable to Dolphin Depredation in a Mediterranean Marine Reserve. ICES J Mar Sci 66:699–707

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Snape RTE, Broderick AC, Çiçek BA, Fuller WJ, Treganza N, et al. (2018) Conflict between Dolphins and a Data-Scarce Fishery of the European Union. Hum Ecol Interdiscip J 46: 423-433

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Geraci ML, Falsone F, Scannella D, Sardo G, Vitale, S, et al. (2019) Dolphin-Fisheries Interactions: An Increasing Problem for Mediterranean Small-Scale Fisheries Examines in Mar Biol and Oceanography 3:1-8

- Pardalou A, Tsikliras A (2020) Factors influencing dolphin depredation in coastal fisheries of the northern Aegean Sea: Implications on defining mitigation measures. Mar Mamm Sci

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Tixier P, Lea MA, Hindell MA, Welsford D, Mazé C, et al. (2013) When large marine predators feed on fisheries catches: Global patterns of the depredation conflict and directions for coexistence. Fish and Fish 00:1–23

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Temple AJ, Kiszka JJ, Stead SM, Wambiji N, Brito A, et al. (2018) Marine megafauna interactions with small-scale fisheries in the southwestern Indian Ocean: a review of status and challenges for research and management. Rev Fish Biol Fish 28:89–115 [Crossref]

[Google Scholor]

- Johannes RE, Freeman MMR, Hamilton RJ (2000) Ignore fishers knowledge and miss the boat. Fish and Fish 1:257−271

[Crossref] [Google Scholor] [Indexed at]

- Giannoulaki M, Markoglou E, Valavanis VD, Alexiadou P, Cuknell A, et al. (2016) Linking small pelagic fish and cetacean distribution to model suitable habitat for coastal dolphin species, Delphinus delphis and Tursiops truncatus, in the Greek Seas (Eastern Mediterranean). Aquatic Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 27:436–451

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Monaco C, Cavallé M, Peri I (2019) Preliminary study on interaction between dolphins and small-scale fisheries in Sicily: learning mitigation strategies from agriculture – Quality-Access to Success. 20:400-407

[Google Scholor]

- Monaco C (2020) Interaction between cetaceans and small scale fisheries in the Mediterranean The case of the Central Mediterranean Sicily Italy Published by Low Impact Fishers of Europe

[Google Scholor]

- Romanov EV, Sabarros PS, Le Foulgoc L, Richard E, Lamoureux JP, et al. (2013) Assessment of depredation level in Reunion Island pelagic longline fishery based on information from self-reporting data collection programme [online] [Crossref]

[Google Scholor]

- European Commission (n.d.) STECF. [online] European MSP Platform (n.d.) Case Study: Straight of Sicily-Malta

- Lauriano G, Fortuna CM, Moltedo G, Notarbartolo di Sciara G (2004) Interactions between common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and the artisanal fishery in Asinara Island National Park (Sardinia): assessment of catch damage and economic loss. J Cetacean Res Manag 6:165–173 [Crossref]

[Google Scholor]

- Rabearisoa N, Guinet C, Guérin P, Bach P (2019) Depredation mitigation device for pelagic longline fisheries: the PARAPED project World Marine Mammal Conference Barcelona December 2019

- Gilman E, Clarke S, Brothers N, Alfaro-Shigueto-J, Mandelman J, et al. (2007) Shark depredation and unwanted bycatch in pelagic longline fisheries: industry practices and attitudes and shark avoidance strategies Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council Honolulu USA

[Google Scholor]

- Gilman E, Brothers N McPherson G, Dalzell P (2006) Review of cetacean interactions with longline gear. J Cetacean Res Manag 8:215-223

[Google Scholor]

- Bearzi G, Bonizzoni S, Gonzalvo J (2011) Dolphins and coastal fisheries within a marine protected area mismatch between dolphin occurrence and reported depredation. Aquat Conserv Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 21:261-267

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Bonizzoni S, Furey NB, Pirotta E, Valavanis VD, Wursig B, et al. (2013) Fish farming and its appeal to common bottlenose dolphins modelling habitat use in a Mediterranean embayment. Aquat Conserv Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 24:696-711

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Debono J (2020) Malta’s bottlenose dolphin population estimated at 79

- Diaz Lopez B (2006a) Interactions between Mediterranean bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and gillnets off Sardinia Italy. ICES J Mar Sci 63:946-951

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Diaz Lopez B (2006b) Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) predation on a marine fin fishfarm: Some underwater observations. Aquat Mamm 32:305–310

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- European Commission STECF

- European MSP Platform Case Study Straight of Sicily-Malta

- Gomerčić MD, Galov A, Gomerčić T, Škrtić D, Ćurković S, et al. (2009) Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) Depredation Resulting in Larynx Strangulation with Gill-Net Parts. Mar Mamm Sci 25:392–401

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Pace DS, Giacomini G, Campana I, Paraboschi M, Pellegrino G, et al. (2019) An integrated approach for cetacean knowledge and conservation in the central Mediterranean Sea using research and social media data sources. Aquat Conserv Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 29:1302-1323

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Monaco C, Aguilera R, Cam iñas JA, Laspina M, Molin AM, et al. (2020) Interactions between cetaceans and small scale fisheries in the Mediterranean Conclusive Report Published by Low Impact Fishers of Europe

[Google Scholor]

- Pace DS, Pulcini M, Triossi F (2012) Anthropogenic food patches and association patterns of Tursiops truncates at Lampedusa island Italy. Behav Ecol 23:254–264

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Panigada S, Labach H (2018) Tursiops truncatus in the Mediterranean and Black Seas

- Pulcini M, Pace DS, La Manna G, Triossi F, Fortuna CM, et al. (2013) Distribution and abundance estimates of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) around Lampedusa Island (Sicily Channel, Italy): implications for their management Cambridge University Press 1175-1184

[Crossref] [Google Scholor]

- Zollet EA, Read AJ (2006) Depredation of catch by bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Florida king mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla) troll fishery. Fish Bull 104:343-349

[Google Scholor]

Citation: Laspina M, Terribile K, Said S (2022) Interactions between Cetaceans and Small-Scale Fisheries around the Central Mediterranean Maltese Islands. J fisheriesci.com Vol:16 No:1