Introduction

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) is arguably the most common disease encountered by the gastroenterologist and its effects are experienced daily by up to 10% of the population [1]. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is now considered the standard surgical approach for treatment of severe Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD).

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with posterior hiatal repair is the commonest surgical technique used. Long-term outcome studies have established that it provides satisfactory clinical outcomes and good control of reflux symptoms in most patients [2].

However, postoperative dysphagia remains a cause of troublesome morbidity at late follow-up in a subset of patients. The literature proposes many possible explanations for post-fundoplication dysphagia, although the causal link between these potential mechanisms and outcomes is still unclear [3].

Surgeons have focused mainly on issues concerning the optimal length of the wrap, fixation of the wrap, mobilization of the gastric fundus/division of the short gastric vessels, and the use of a bougie intraoperatively [4].

Two aspects of surgical technique have been shown unequivocally to have an impact on postoperative dysphagia: the technique used to construct the fundoplication and the method of hiatal closure. Most studies have focused on construction of the fundoplication with less attention being paid to the technique of closure of the esophageal hiatus. Although, closure of the esophageal hiatus is also an important technique as it prevents postoperative hiatal herniation, if excessively narrowed, the repair can also cause dysphagia [5].

Traditionally, closure has been achieved using posteriorly placed sutures. It is also possible to reduce the hiatal size using an anterior hiatal repair technique, and it has been hypothesized that anterior repair may achieve a more ‘‘anatomic’’ end result due to less anterior displacement of the esophagus thus keeping its axis straight. This might result in less postoperative dysphagia [5].

To test this hypothesis, we have undertaken a prospective doubleblind randomized trial of anterior vs posterior hiatal repair during laparoscopic fundoplication.

Patients and Methods

Study population

This study is a prospective study conducted in KasrElainy School of Medicine, Cairo University on 18 patients presenting by Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) with or without hiatus hernia. This study was performed over a period of 18 months from January 2013 to June 2014.

Inclusion criteria

In brief, patients with proven gastro-esophageal reflux disease (presenting by regurgitation and heartburn or esophagitis and esophageal ulceration at endoscopy) were considered for entry into the study. Patients with respiratory complications were also included in this study. The studied population had an age range from 20-70.

Exclusion criteria

Patients suffering from esophageal motility disorders and recurrence following anti reflux surgery were excluded.

Preoperative assessment

All patients were enquired about their lifestyle, habits of medical importance (smoking and alcohol intake) and the previous use of anti-reflux medications.

In addition to the routine labs (blood picture, liver and renal function tests), patients were subjected to contrast studies (barium swallow and meal) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (with biopsy when needed).

A formal consent was signed by all patients. Fundoplication was described for all patients and the possible complications (including pain, wound complications, recurrence, dysphagia, bleeding and esophageal or gastric injury) were discussed.

Randomization

This is a prospective, single blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Patients were randomised to undergo laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication either with anterior or posterior hiatal repair. Randomization occurred in the operating room after the commencement of anesthesia by opening a pre-sealed envelope. Patients were blinded perioperatively to which procedure had been performed. Both techniques were performed by the same surgical team to standardize the procedure. No patients were withdrawn from the study after randomization. The Research and Ethics Committee of Kasr Elainy School of Medicine, Cairo University approved the protocol.

Operative technique

• Positioning: The patient lies supine on the operating table in reverse trendlenberg position. After induction of anesthesia, an orogastric tube is inserted to decompress the stomach.

• 1st Port: A skin incision, 14 cm inferior to the xiphoid process, in the midline or 1–2 cm to the left of the midline, is done by the scalpel and by the help of two forceps the linea alba and the peritoneum were breached by the use of fine scissor. A 10 mm port with its trochar is inserted then the trochar is removed (Hasson method).

• Insufflation: is the next step until optimum abdominal pressure reaches 14 mmHg.

• Camera–30 degree is then introduced through the 1st port and the whole abdomen is inspected for any possible iatrogenic injuries during the Introduction of the port.

• 2nd Port is placed in the left mid clavicular line at the same level with 1st port, and it is used for insertion of a Babcock clamp or for devices used to divide the short gastric vessels.

• 3rd Port is placed inthe right mid-clavicular line at the same level of the other two ports, and it is used for the insertion of a retractor to lift the left lateral segment of the liver.

• 4th& 5th Ports are placed under the right and left costal margins. They are used for the dissecting and suturing instruments.

• Inspection of the esophageal hiatus (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wide esophageal hiatus.

• Gastrohepatic ligament is divided, beginning above the caudate lobe of the liver, where the ligament is usually very thin, and continuing toward the diaphragm until the right crus is identified (Pars Flacida) ( Figure 2).

Figure 2: Division of gastrohepatic ligament.

• The right crus is then separated from the right side of the esophagus by blunt dissection and continued inferiorly toward the junction with the left crus (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Dissection of the right crus.

• Posterior vagus nerveis identified and preserved.

• The phreno-esophageal membrane and the peritoneum above the esophagus are transected with the ultrasonic scalpel.

• The left crus of the diaphragm are dissected bluntly downward toward the junction with the right crus.

• Anterior vagus nerve is identified and preserved (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Dissection of left crus.

• Short Gastric Vessels are divided; starting at the level of the middle portion of the gastric body until the most proximal short gastric vessel is divided, using a laparoscopic ultrasonic scalpel instrument which is introduced through the 2nd port. A grasper is introduced through the 5th port and held by the surgeon, while an assistant applies traction on the greater curvature of the stomach through the 4th port (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Dissection of short gastric vessels.

• A window between the esophagus and both diaphragmatic crura is opened by a combination of blunt and sharp dissection. The window is then enlarged and a Penrose drain is passed around the esophagus, incorporating both the anterior and the posterior vagus nerves (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Creation of retro-esophageal window.

• Closure of the Crura

(a) 50% of the studied population had anterior crural "hiatal" repair; two non-absorbable polyamide sutures "Ethibond" are used to approximate the crura anterior to the esophagus (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Anterior crural "hiatal" repair.

(b) 50% of the studied population had posterior crural "hiatal" repair; two non-absorbable polyamide sutures "Ethibond" are used to approximate the crura posterior to the esophagus (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Posterior crural "hiatal" repair.

(c) 360 Degree Fundal Wrap: is done. The left and right sides ofthe fundus are wrapped,in a tension-free "floppy" way, around the esophagogastric junction. A Babcock clamp introduced through the 2nd port is used to hold the two flaps together during placement of the first stitch. The two edges of the wrap are secured to each other by three 2-0 non-absorbable polyamide suture "Ethibond" placed at 1 cm of distance from each other (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Total "360 degree" fundoplication.

(d) Hemostasis is achieved; the instruments and the trocars are removed from the abdomen under direct vision without drain.

Postoperative care

All patients are sent to the surgical ward without a nasogastric tube. Patients are fed the morning of the first postoperative day with clear liquids and then a soft diet, and are instructed to avoid meat, bread and carbonated beverages for the following 2 weeks. Patients are discharged within 24h-48h. Most patients resume their regular activity within 2 weeks.

Results

All patients had laparoscopic nissen fundoplication. The study population was divided, according to the type of hiatal repair, into two groups:

Group A: 9 patients had anterior hiatal repair and

Group B: 9 patients had posterior hiatal repai.

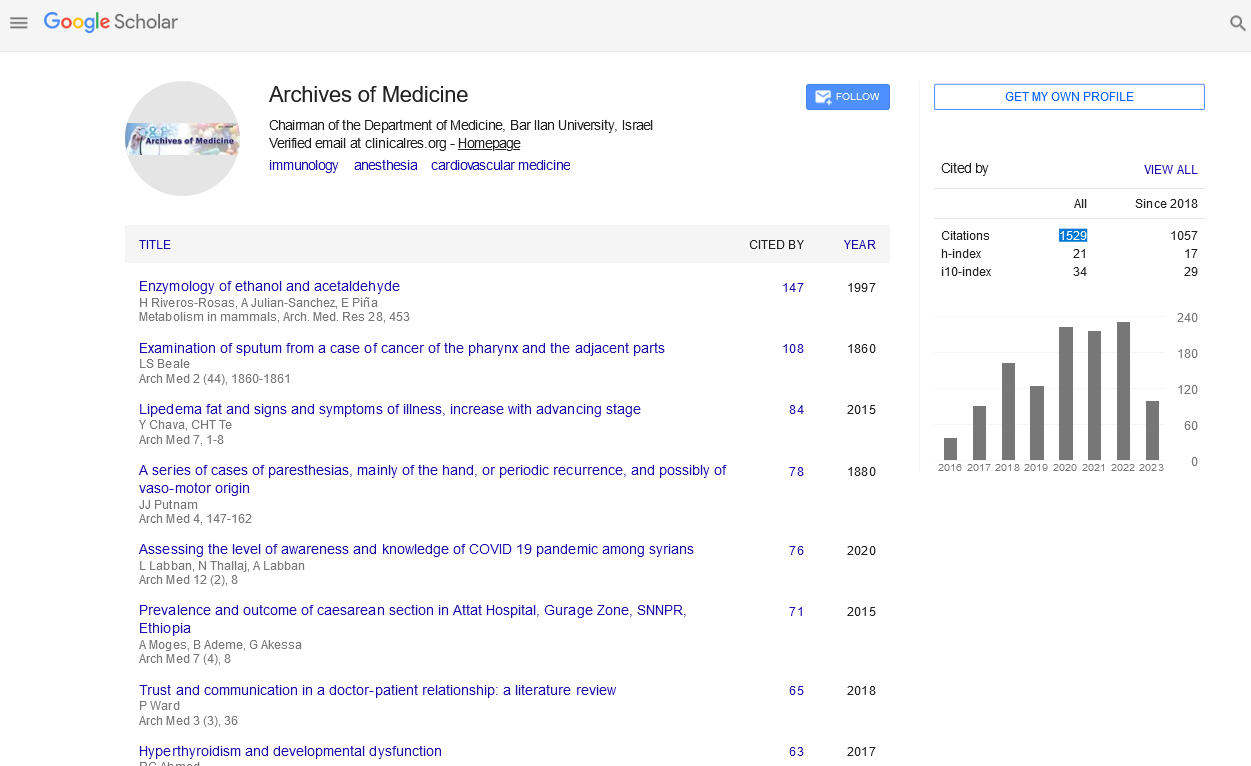

The age of the studied population ranged from 28 to 41 years with average of 34.5 years, 11 males and 7 females (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Sex distribution.

Post-operative dysphagia

Post-operative dysphagia was assessed using Mellow–Pinkas- Score for dysphagia:

0 = able to eat normal diet/no dysphagia.

1 = able to swallow some solid foods.

2 = able to swallow only semi solid foods.

3 = able to swallow liquids only.

4 = unable to swallow anything/total dysphagia.

(Tables 1 and 2)

| Dysphagia Score |

Group A

No. of Patients |

Percentage |

| 0 |

8"a" |

88.8% |

| 1 |

0 |

0% |

| 2 |

1"b" |

11.2% |

| 3 |

0 |

0% |

| 4 |

0 |

0% |

Comments:

"a": One of those 8 patients had difficulty to swallow water only.

"b": This patient had difficult eructation and sense of bloating.

Table 1: Dysphagia in group A.

| Dysphagia score |

Group B

No. of Patients |

Percentage |

| 0 |

7 |

77.7% |

| 1 |

2"c" |

22.3% |

| 2 |

0 |

0% |

| 3 |

0 |

0% |

| 4 |

0 |

0% |

Comments:

"c": Both patients had difficulty in swallowing solids but it was strange enough that it wasn’t on regular basis.

Table 2: Dysphagia in Group B.

All patients who suffered post-operative dysphagia were advised to have endoscopic dilation and they showed marked improvement.

Failed anti-reflux "Recurrence"

All patients in this study were followed up for improvement of GERD symptoms and for recurrence of their pre-operative complaint over a period of 18 months.

Out of the 18 patients included in this study, one patient of "Group B", had symptoms of GERD in the form of heartburn which was relieved by a short course of proton pump inhibitor "PPI".

Discussion

Nissen fundoplication has undergone many modifications to minimize the side effects of the procedure. In undertaking the surgery, surgeons have focused mainly on issues concerning the optimal length of the wrap, fixation of the wrap, mobilization of the gastric fundus/division of the short gastric vessels, and the use of a bougie intraoperatively [4].

Less attention has been paid to the technique of closure of the esophageal hiatus though it might have an impact on the risk of post-fundoplication dysphagia and hiatal herniation. In the early 1990’s, the esophageal hiatus was not repaired routinely and a high incidence of herniation of the wrap and stomach was reported [6].

Previous studies have shown that not all dysphagia following Nissen fundoplication is due to the construction of the fundoplication but that it can also develop following overly tight hiatal repair or post-fundoplication scarring at the esophageal hiatus (hiatal stenosis) [7].

Our study in 2013-2014 was done based on the anatomical hypothesis, that states that the anterior repair of the hiatus decreases the anterior angulation of the esophagus, as a trial to reach the most suitable technique thus minimizing post-operative dysphagia and optimizing management of GERD. Watson et al. commenced a randomized controlled trial in 1997 to investigate the possibility that post–Nissen fundoplication dysphagia might be less common after anterior hiatal repair. The hypothesis was that after posterior hiatal repair, the esophagus is displaced anteriorly (as observed on barium swallow radiographic films), and this angulation might contribute to postoperative dysphagia [8].

In our study, 18 patients with gastro esophageal reflux disease underwent laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Nine patients had anterior hiatal repair "Group A" and nine patients had posterior hiatal repair "Group B". Both groups had 360-degree wrap, hence the difference was only in the hiatal repair.

In fact, our results showed no significant difference in dysphagia between patients undergoing anterior hiatal repair compared to those with posterior hiatal repair.

This is very much in concordance with the results of Watson et al. in their study published in 2001. Similar to our study design, they randomized a total of 102 patients with gastro esophageal reflux to undergo laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with either anterior (47 patients) or posterior (55 patients) repair of the diaphragmatic hiatus. Both groups underwent a 360° Nissen fundoplication. Hence, the technique of hiatal closure was the only difference [8].

In our study, two patients out of the 9 patients of "Group A" had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity with anterior hiatal repair for GERD. One of them had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the same setting. All procedures were completed laparoscopically.

Watson et al. stated that 6 months after surgery symptoms of postoperative dysphagia were not influenced by the hiatal repair technique and therefore concluded that anterior hiatal repair seems to be at least as good as posterior repair during laparoscopic fundoplication in the short-term [8].

A further study performed by Wijnhoven et al. investigated the results of the 5 year follow up of the patients who were randomized in Watson's study into these two groups. In harmony with the results of our study, again during the 5 year follow up, there were no significant differences between the groups for the percentage of patients with dysphagia [4].

However, the long-term (10 year) follow up study by Chew et al. which was again performed on the same study subjects of Watson's study, brought some new light into the subject. Chew et al. found that more patients in the posterior hiatal repair group reported dysphagia for lumpy solids [5].

In our study, the short term follow up for post-operative dysphagia is:

• Group A: one patient had sense of bloating with difficult eructation and was able to swallow semi-solids only, while eight patients had no symptoms of dysphagia except for one who had difficulty swallowing water.

• Group B: two patients had difficulty swallowing some solids but not on regular basis, while seven patients had no dysphagia.

As mentioned above Chew et al. during their 10 year follow up found more patients in the posterior hiatal repair group complaining of dyspahgia than in the anterior hiatal repair group but there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding bloating and inability to belch [5].

In our study, the short term follow up for recurrent GERD "failed anti-reflux" is:

• Group A: no patients had recurrent heartburn, epigastric pain or regurgitation.

• Group B: one patient had episodes of heartburn controllable by short courses of proton pump inhibitors "PPI".

• No patients were operated upon for failed anti-reflux

Wijnhoven et al. reported, in the 5 year follow up, that fewer patients in the anterior repair group experienced symptoms of heartburn. No patients underwent re-operation for recurrent gastro esophageal reflux [4].

Chew et al. reported, in the 10 year follow up study, that there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding symptoms associated with gastro esophageal reflux [5].

The difference in the follow up results between our study and Wijnhoven and Chew et al. is due to the difference in the size of the studied population and the duration of the follow up period thus it is highly possible to reach the same results on the long term follow up.

Valderrama et al. reported aortic injury during mesh fixation in esophageal hiatoplasty. He also reported that it was the 4th reported case [9]. However, in our study we believe that anterior repair of the crura would be safer than the posterior repair due to the posterior relation of the aorta to the esophagus.

In our study, by the end of the 1st post-operative year, 89% of "Group A" patients and 78% of "Group B" patients were satisfied by the procedure regarding post-operative dysphagia. However, 100% of "Group A" and "Group B" patients were satisfied due to relief of GERD. Ultimately, the measure of success after a surgical procedure is determined by the patient’s view of the outcome, rather than the surgeon’s opinion or the results of various investigations.

Although Wijnhoven et al. had a longer follow up period, patient satisfaction was similar to our study and 84% of the patients of the anterior group and 83% of the posterior group were satisfied [4]. Overall satisfaction was 91% for the anterior group, 86% for posterior group at the 10th post-operative year [5].

In our study, it is worth saying that it was difficult to close the hiatus anterior to the esophagus in the first cases but the learning curve was rising quite well that it was feasible and easy as the posterior repair.

Conclusion

At the beginning of this study, we thought that anterior hiatal repair is more satisfactory than posterior hiatal repair regards post-operative dysphagia. Although the short term follow up showed no privilege of anterior over posterior hiatal repair, long term follow up studies should be done to conform this outcome.

Anterior repair is more convenient regarding the possibility of aortic injury, although more difficult but the learning curve is satisfactory.

More randomized controlled studies with large population number and longer follow up period is needed to get standardized guide lines.

6743

References

- Salminen P,Hiekkanen H, Laine S, Ovaska J (2007) Surgeons' experience with laparoscopic fundoplication after the early personal experience: does it have an impact on the outcome? SurgEndosc 21: 1377-1382.

- Kelly JJ, Watson DI, Chin KF, Devitt PG, Game PA, et al. (2007) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: clinical outcomes at 10 years. J Am CollSurg 205: 570-575.

- Wills VL, Hunt DR (2001) Dysphagia after antireflux surgery. Br J Surg 88: 486-499.

- Wijnhoven BP, Watson DI, Devitt PG, Game PA, Jamieson GG (2008) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with anterior versus posterior hiatal repair: long-term results of a randomized trial. Am J Surg 195: 61-65.

- Chew CR, Jamieson GG, Devitt PG, Watson DI (2011) Prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with anterior versus posterior hiatal repair: late outcomes. World J Surg 35: 2038-2044.

- Seelig MH, Hinder RA, KlinglerPJ, Floch NR, Branton SA, et al. (1999) Paraesophageal herniation as a complication following laparoscopic antireflux surgery. J GastrointestSurg 3: 95-99.

- Hunter JG,Swanstrom L, Waring JP (1996) Dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. The impact of operative technique. Ann Surg 224: 51-57.

- Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Devitt PG, Kennedy JA, Ellis T, et al. (2001) A prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with anterior vs posterior hiatal repair. Arch Surg 136: 745-751.

- Cano-Valderrama O,Marinero A, Sánchez-Pernaute A, Domínguez-Serrano I, Pérez-Aguirre E, et al. (2013) Aortic injury during laparoscopic esophageal hiatoplasty. SurgEndosc 27: 3000-3002.