Keywords

Influenza; Pandemic influenza; Live attenuated influenza vaccine; Pandemic vaccine; Preclinical and clinical trials; Safety; Immune response.

Abbreviations

att: Attenuation; ca: Cold-Adaptation; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CD4+: T Helper Lymphocyte; CD8+: Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte; EID: Embryo Infectious Dose; HA: Hemagglutinin; HPAIV: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus; IEM, Institute of Experimental Medicine; Ig: Immunoglobulin; LAIV: Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine; Len-MDV: A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) Master Donor Virus; MDV: Master Donor Virus; NA: Neuraminidase; NIBSC: The National Institute for Biological Standards and Control; RDE: Receptor-Destroying Enzyme; RG: Reverse Genetics; ts: Temperature Sensitivity; UV: Ultraviolet; WHO: World Health Organization; WT: Wild-Type.

Introduction

Vaccination is considered an essential public health tool to control both seasonal epidemic and pandemic influenza. Several types of influenza vaccines (inactivated and live attenuated) and production technologies (egg- or cell derived vaccines and vaccines generated by reverse genetics) exist. World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges benefits of vaccination with live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) in controlling epidemic and pandemic influenza [1,2]. In contrast to inactivated vaccines, LAIVs are capable of inducing broad-spectrum and long-lasting immune responses, making them an attractive option for pandemic preparedness, especially in countries with very high population density. Furthermore, WHO considers the expansion of LAIV production as a promising strategy to increase influenza vaccine supply in pandemic situation [3].

Two live-attenuated, cold-adapted vaccines are currently manufactured in Russia (Microgen) [4] and in the USA (MedImmune) [5]. The LAIV consists of reassortant viruses, which contain hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) gene segments from circulating wild-type (WT) viruses of interest on a backbone of the remaining six internal protein genes derived from the attenuated master donor viruses (MDVs) (genomic composition 6 MDV genes: 2 WT genes). A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) (Len-MDV) and B/USSR/60/69 MDVs are currently used in Russia as MDVs for LAIV [6]. Although LAIVs have been under development for more than 40 years and were proved to be safe and effective, there is still a room for their improvement, especially during the development of pandemic LAIV candidates.

Reassortants for Russian LAIV are being produced by the Institute of Experimental Medicine (IEM, St Petersburg, Russia). IEM supplies the LAIV reassortants to the Russian manufacturer Microgen (Moscow). Besides that, Russian-backbone LAIV seed viruses are provided to some developing countries interested in the establishment their own national LAIV productions (India, Thailand, and China) through an intellectual property transfer program initiated by WHO [7]. To date, Russian-backbone 2009 pandemic and seasonal LAIVs are registered in India, and 2009 pandemic LAIV is registered in Thailand. In addition, clinical trials of the 2009 pandemic vaccine are ongoing in China.

MedImmune seasonal and pandemic LAIV viruses are currently produced by the means of reverse genetics (RG) [8]. In contrast, Russian LAIVs are being produced by classical genetic reassortment in embryonated eggs. Regardless of the preparation method, LAIV candidates retain the temperature-sensitive (ts) and coldadapted phenotypes typical for the MDVs.

Using reverse genetics to prepare LAIV viruses is restricted by the need to purchase a license from the patent holders. The RG approach allows generating reassortant viruses with any desired genomic composition by combining a set of specific plasmids encoding all necessary genes. In contrast, classical method leads to predominant selection of high-growth reassortants. As a result, vaccine candidates generated by classical technique may have higher yield in eggs than reassortants generated by reverse genetics. This advantage of classical approach is especially important for the preparation of vaccines based on pandemic viruses, which are usually grow poorly in eggs.

Taken together, reverse genetics system allows artificial manipulating with influenza virus

genome and is a powerful tool to generate reassortants with desired genomic composition in vitro. However, some pandemic vaccine productions were confronted with such difficulties as the low yield of the PR8-based RG reassortants [9]. Most probably, these candidates would have grown to much higher titers if they had been produced by classical reassortment in eggs. It must be kept in mind that availability of influenza vaccines during a pandemic will largely depend on the vaccine virus yield.

Co-infection procedures

Rapid strategy for the development of cold-adapted live attenuated influenza vaccines is of high importance, especially in the event of a pandemic [10]. Co-infection step plays a key role in the classical genetic reassortment. Multiple studies have attempted to evaluate reassortment efficiencies of wild-type and cold-adapted viruses using different variants of crossing procedures, such as simultaneous [11-26] or successive [27-29] inoculation of two parental viruses. Co-infection procedures also differed by infectivity ratio of the viruses, temperature of incubation and culturing substrate (eggs or cell culture). Most of the recent studies describe reassortment of live parental viruses [11-15,20,22-26]. However, the reassortment efficiency can be substantially improved if one of the parental viruses is inactivated prior to co-infection. A phenomenon of reactivation of partially or completely inactivated influenza virus by crossing with another live virus was discovered and studied in 1950s [16,17,27- 29], and was later used in some studies [18,19,21]. A short summary of different co-infection variants is shown in the Table 1.

| |

|

Temperature of incubation |

Parental viruses |

Ref. |

| Var.1 |

Substrate |

Infectivity ratio |

Sequence of infection2 |

live + live |

live + inactivated |

| |

|

Optimal3 |

Low4 |

1: 1 |

Another |

Simultaneously |

Successively |

UV5 |

Heat |

|

| 1 |

Eggs |

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

|

[11-15] |

| 2 |

|

É |

|

|

É |

É |

|

|

É |

|

[16-19] |

| 3 |

|

É |

|

|

É |

|

É |

|

|

É |

[27,28] |

| 4 |

|

É |

|

|

É |

É |

|

|

|

É |

[12,13,21] |

| 5 |

Cells |

|

É |

|

É |

É |

|

É |

|

|

[14] |

| 6 |

|

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

|

[22] |

| 7 |

|

|

É |

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

|

[20] |

| 8 |

|

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

|

[23-26] |

| 9 |

|

É |

|

|

É |

|

É |

|

É |

|

[29] |

1Variant number.

2Sequence of infection of sensitive substrate (eggs, cells) with parental viruses.

332°C-37°C.

425°C.

5Ultraviolet irradiation.

Table 1: Different variants of the co-infection step of reassortment procedure (Development of reassortants of wild type virus with cold-adapted or wild type virus).

Despite a number of reassortment procedure variants, a classical reassortment technique is most widely used for the development of Russian LAIV reassortants, which includes simultaneous co-infection of embryonated chicken eggs with equal infection doses of wild type parental strain and MDV (variant #1 in the Table 1). Briefly, a co-infection step is followed by 6-7 rounds of selective propagation, including three passages at the low temperature of 25-26°C. The generation and selection of reassortants are carried out in the presence of rabbit, ferret or rat anti-MDV serum treated with RDE. Cloning by endpoint dilution is performed at each of the last 3-4 passages [13,18,19].

It should be noted, that in some cases (variant #2 in the Table 1) the vaccine strains may be only prepared using the modified classical reassortment procedure [18].

Obstacles in obtaining 6:2 reassortants and some new methodological approaches for the development of Russian Pandemic Laivs

Little is known about the mechanisms underlying the reassortment of influenza virus gene segments in a cell simultaneously infected with two different viruses. Gene compatibility of the two parental viruses can limit the number of emerging reassortant variants. It was previously demonstrated that phenotypical properties of WT parental viruses might significantly influence the reassortment efficiency after co-infection with cold-adapted MDVs. Similar to virus antigenic properties, the ts phenotype of influenza A and B circulating viruses is undergoing evolutionary changes demonstrating apparently cyclic patterns: while the most of the new antigenic drift variants and all pandemic viruses are able to grow at high temperatures (temperature resistance, non-ts phenotype), the antigenically evolved WT viruses tend to become temperature sensitive [30,31].

Based on the experiences gained during the past two decades generating seasonal and pandemic LAIVs by classical reassortment technique, the highest percentage of reassortants with vaccine 6:2 genotype could be achieved when WT parental virus was resistant both to high temperatures (38-40°C) and to non-specific serum inhibitors [15,32]. For instance, a novel swineorigin influenza A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) pdm virus was found to be non-ts and inhibitor resistant, and during the process of its reassortment with Len-MDV 33 out of 34 isolated clones inherited HA an NA from WT virus and displayed 6:2 genomic composition [31].

Reassortment of Len-MDV with another swine-origin influenza A/Indiana/10/2011 (H3N2)v human virus characterized by nonts phenotype also resulted in generation of reassortants with predominantly vaccine 6:2 genotype (unpublished data).

This was in contrast with reassortment results when ts and inhibitor sensitive seasonal WT influenza viruses were crossed with ts and inhibitor resistant MDV; the number of 6:2 vaccine reassortants was very limited, while the majority of reassortants was of 7:1 genomic composition [33]

Mismatch of HA and NA of H5 avian influenza viruses during reassortment with Len-MDV was also repeatedly demonstrated for a number of H5 viruses [12,15,18,32-35]. Of note, generation of reassortants between highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (HPAIVs) and MDV by classical technique in embryonated chicken eggs is impossible because the HPAIVs are lethal for the embryos. For the development of Russian pandemic LAIVs against HPAIVs reassortants for inactivated vaccine subtype H5N1 on PR8 backbone (H5N1/PR8-RG) have been chosen as a source of surface proteins. The HAs of the H5N1/PR8-RG viruses were engineered to remove four basic amino acids from the HA cleavage site, resulting in viruses that were considered attenuated for birds and safe for humans. The procedure of the HA modification was described in Subbarao et al. [36]. Unfortunately, all the attempts to recover LAIV reassortant candidates bearing avian neuraminidase N1 were ineffective; no 6:2 reassortants have been generated. Reassortment of the MDV with the H5N1/PR8-RG viruses either resulted in 7:1 reassortants

The phenomenon of predominant inclusion of one gene over another into genome of the reassortant progeny has not been fully elucidated. One possible reason could be the selection of the most viable and high-growth variants from a mixture of all possible reassortants, which is the limitation of the classical reassortment procedure. In case of co-infection of H5 influenza viruses with Len-MDV, only 7:1 reassortants could be successfully selected. Indeed, these 7:1 reassortants grow in embryonated chicken eggs better than the corresponding 6:2 reassortants [34]. These data are in concordance with a study by Horimoto et al. [9]. The authors created reassortants between H5N1 WT and PR8 viruses and showed that the 7:1 reassortant grew significantly better than the one with 6:2 genome composition.

The influence of the length of the NA stalk on the efficiency of virus replication was revealed in several studies [37-40]. Castrucci and Kawaoka [38] demonstrated that the longer the NA stalk, the better the influenza virus replicates. We compared the length of the NA stalk domains of Len-MDV and two H5N1 viruses, which were used for the development of pandemic LAIV candidates: NIBRG-23 (A/turkey/Turkey/1/2005) and VNH5N1-PR/CDCRG (A/Vietnam/1203/2004). Sequence alignment analysis of genes coding for NAs of A/turkey/Turkey/1/2005 (H5N1) (EPI118777), A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) (EPI361525) and A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) (EPI555084) influenza viruses revealed that the NAN2 stalk domain of the Len-MDV is 20 amino acids longer than that of NAN1 of the H5N1 parental viruses (data not shown). This difference may be also a reason of benefit of Len-MDV NA gene during the reassortment of the MDV with H5N1 viruses

Preclinical testing of Russian Pandemic Laivs

Eight Russian pandemic LAIV candidates were prepared by classical reassortment in embryonated chicken eggs on the Len- MDV backbone [18,34,35,41,42]. Four of them had 6:2 genomic composition, and the remaining for were 7:1 genotype (Table 2). The attenuated phenotype of the vaccine candidates was confirmed using virological methods (determination of range of temperature sensitivity and cold adaptation during reproduction in embryonated chicken eggs), molecular genetics methods (fullgenome sequencing), and in experiments on laboratory animals (mice, guinea pigs, ferrets, chicken) (Table 3).

| Live attenuated vaccine for pandemic influenza1 / WT parents |

The source of genes |

Ref. |

| HA |

NA |

Other |

| 1 |

LAIV (7:1)2 |

A/17/duck/Potsdam/86/92 (H5N2) |

WT |

MDV3 |

MDV |

[35] |

| |

WT |

A/duck/Potsdam/1402-6/86 (H5N2) |

WT |

WT |

WT |

|

| 2 |

LAIV (7:1) |

A/17/turkey/Turkey/05/133 (H5N2) |

WT |

MDV |

MDV |

[18,34] |

| |

WT4 |

NIBRG-23 (H5N1)5 |

WT |

WT |

PR8 |

|

| 3 |

LAIV (7:1) |

A/17/Vietnam/2004/65107 (H5N2) |

WT |

MDV |

MDV |

[18,34] |

| |

WT4 |

VNH5N1-PR/CDC-RG (H5N1)5 |

WT |

WT |

WT |

|

| 4 |

LAIV (7:1) |

A/17/Indonesia/05/4342 (H5N2) |

WT |

MDV |

MDV |

[18] |

| |

WT4 |

CDC-RG25 |

WT |

WT |

PR8 |

|

| 5 |

LAIV (6:2) |

A/17/mallard/Netherlands/00/95 (H7N3) |

WT |

WT |

MDV |

[41] |

| |

WT |

ÃÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ/mallard/Netherlands/12/00 (H7N3) |

WT |

WT |

WT |

|

| 6 |

LAIV (6:2) |

A/17/California/66/395 (H2N2) |

WT |

WT |

MDV |

[42] |

| |

WT |

A/California/1/66 (H2N2) |

WT |

WT |

WT |

|

| 7 |

LAIV (6:2) |

A/17/Anhui/2013/61 (H7N9) |

WT |

WT |

MDV |

Unpublished |

| |

WT |

A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9) |

WT |

WT |

WT |

|

| 8 |

LAIV (6:2) |

ÃÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ/17/Indiana/11/72 (H3N2)v |

WT |

WT |

MDV |

Unpublished |

| |

WT |

ÃÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ/Indiana/10/2011 (H3N2)v |

WT |

WT |

WT |

|

1LAIV candidates were obtained by classical reassortment in hens’ eggs.

2Genomic composition.

3A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) master donor virus, MDV.

4Cleavage site of HA of WT parental virus was genetically modified.

5Reassortants for inactivated vaccine subtype H5N1, H5N1/PR8-RG (termed NIBRG-23, VN-PR8/CDC-RG, and CDC-RG2) prepared from A/turkey/

Turkey/1/05, A/Vietnam/1203/2004, and A/Indonesia/5/2005 avian influenza viruses with PR8 strain as a donor of internal genes. PR8-based

reassortant viruses were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC, USA). The HA H5N1/PR8-RG viruses was engineered to remove four

basic amino acid codons from the cleavage site of HA.

Table 2: List of pandemic LAIV candidates prepared by classical reassortment in embryonated chicken eggs on the A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2)

master donor virus backbone.

| Live attenuated vaccine for pandemic influenza1 |

Reproductive capacity2 at the t°C of |

Ref. |

Attenuated for |

Ref. |

Phenotype |

| 32-33°C |

25-26°C |

39-40°C |

| LAIV (7:1)3 |

A/17/duck/Potsdam/86/92 |

9.3 |

6.2 |

1.5 |

[35] |

Mice, chicken, |

[35,47] |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H5N2) |

|

|

|

|

monkey |

|

|

| LAIV (7:1) |

A/17/turkey/Turkey/05/133 |

8.7 |

7.2 |

<1.7 |

[34] |

Mice, ferrets, |

[10,34] |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H5N2) |

|

|

|

|

chicken |

|

|

| LAIV (7:1) |

A/17/Vietnam/2004/65107 |

9.2 |

7.7 |

<1.7 |

[34] |

Mice, ferrets, |

[34] |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H5N2) |

|

|

|

|

chicken |

|

|

| LAIV (7:1) |

A/17/Indonesia/05/4342 |

10.2 |

7.2 |

1.2 |

Unpublished |

Mice, guinea pigs |

Unpublished |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H5N2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LAIV (6:2) |

A/17/mallard/Netherlands/00/95 |

9.5 |

7.0 |

1.8 |

[41] |

Mice, guinea pigs, |

[41,43,48] |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H7N3) |

|

|

|

|

chicken, ferrets |

|

|

| LAIV (6:2) |

A/17/California/66/395 |

9.0 |

6.6 |

<1.2 |

[42] |

Mice, ferrets |

[42] |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H2N2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LAIV (6:2) |

A/17/Anhui/2013/61 |

10.2 |

7.6 |

<1.7 |

Unpublished |

Mice, guinea pigs |

Unpublished |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H7N9) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LAIV (6:2) |

ÃÂÂÂÂÂÂÂ/17/Indiana/11/72 |

9.6 |

8.0 |

<1.7 |

Unpublished |

Mice, guinea pigs |

Unpublished |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H3N2)v |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MDV |

A/Leningrad/134/17/57 |

9.2 |

6.7 |

<1.7 |

[34,44,45] |

Mice, ferrets |

[6,45] |

ts/ca/att |

| |

(H2N2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1LAIV candidates were obtained by classical reassortment in chicken eggs.

2log10 EID50/mL.

3Genomic composition.

Table 3: Attenuated phenotype of pandemic LAIV candidates (preclinical studies).

Vaccine viruses were considered as possessing ts phenotype if their titer in 10-11 days old embryonated chicken eggs at elevated temperatures over 39°C was ≤ 4.2 log10 EID50/mL. Viruses were considered as having a ca phenotype if their titer at low temperature of 25-26°C was ≥ 5.7 log10 EID50/mL [43]. The results showed that all the reassortants exhibited high reproductive activity at an optimal incubation temperature of 32-33°C (9.0- 10.2 log10 EID50/mL). Similar to Len-MDV, vaccine candidates acquired the ts and ca phenotypes, regardless of their genomic composition (6:2 or 7:1). They efficiently reproduced at a lower temperature of 25-26°C (6.2-8.0 log10 EID50/mL) and almost lost the ability to reproduce at the temperature elevated to 39- 40°C (Table 3). Therefore, vaccine viruses retained phenotypic characteristics (cold adaptation and temperature sensitivity) of Len-MDV [34, 44,45].

The presence of all attenuating mutations described for Len-MDV [44,46] within the internal protein genes of the vaccine candidates was confirmed by full-genome sequencing. Experiments on different animal models demonstrated safety and attenuated phenotype of all the egg-grown pandemic LAIV reassortants [34,35,41,43,47,48].

Although there was no direct comparison of related 7:1 and 6:2 LAIV candidates in clinical trials, a comparative study of two LAIV candidates based on A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (H5N1) HPAIV with either 7:1 or 6:2 genotype was done in a ferret model [34]. The study demonstrated that both 7:1 H5N2 LAIV and 6:2 H5N1 LAIV were equally immunogenic for animals.

Phase I clinical trials of Russian Pandemic Laivs

To date Phase I clinical trials of five pandemic LAIVs based on Len-MDV have been completed. The results of four of them have been published (Table 5): A/17/duck/Potsdam/86/92 (H5N2) LAIV [49-51], A/17/mallard/Netherlands/00/95 (H7N3) LAIV [43], A/17/California/66/395 (H2N2) LAIV [52], and A/17/turkey/ Turkey/05/133 (H5N2) LAIV [53].

| Outcomes |

Post dose 1 |

Post dose 2 |

| Vaccine, n/N (%) |

Placebo, n/N (%) |

Vaccine, n/N (%) |

Placebo, n/N (%) |

| H5N2 LAIV based on 7:1 A/17/duck/Potsdam/86/92 vaccine candidate [49-51] |

| Any solicited reaction1 |

0/20 (0) |

Nt2 |

0/20 (0) |

Nt |

| |

Local reaction |

8/20 (40.0) |

Nt |

0/20 (0) |

Nt |

| Systemic reaction |

0/20 (0) |

Nt |

0/20 (0) |

Nt |

| Any serious adverse event |

0/20 (0) |

Nt |

0/20 (0) |

Nt |

| H5N2 LAIV based on 7:1 A/17/turkey/Turkey/05/133 vaccine candidate [53] |

| Any solicited reaction |

12/30 (40.0) |

4/10 (40.0) |

6/30 (20.0) |

4/10 (40.0) |

| |

Local reaction |

2/30 (6.7) |

0/10 (0) |

1/30 (3.3) |

0/10 |

| Systemic reaction |

12/30 (40.0) |

4 (40.0) |

6/30 (20.0) |

4/10 (40.0) |

| Any serious adverse event |

0/30 (0) |

0/10 (0) |

0/30 (0) |

0/10 (0) |

| H7N3 LAIV based on 6:2 A/17/mallard/Netherlands/00/95 vaccine candidate [43] |

| Any solicited reaction |

11/30 (36.7) |

4/10 (40.0) |

5/29 (17.2) |

1/10 (10.0) |

| |

Local reaction |

2/30 (6.7) |

1/10 (10.0) |

1/29 (3.4) |

0/10 (0) |

| Systemic reaction |

11/30 (36.7) |

4/10 (40.0) |

5/29 (17.2) |

1/10 (10.0) |

| Any serious adverse event |

0/30 (0) |

0/10 (0) |

0/29 (0) |

0/10 (0) |

| H2N2 LAIV based on 6:2 A/17/California/66/395vaccine candidate [52] |

| Any solicited reaction |

13/28 (46.4) |

5/10 (50.0) |

9/28 (32.1) |

2/10 (20.0) |

| |

Local reaction |

4/28 (14.3) |

2/10 (20.0) |

0/28 (0) |

0/10 (0) |

| Systemic reaction |

13/28 (46.4) |

4/10 (40.0) |

9/28 (32.1) |

2/10 (20.0) |

| Any serious adverse event |

0/28 (0) |

0/10 (0) |

0/28 (0) |

0/10 (0) |

1Number of subjects presenting event.

2Not tested: placebo group was not included in clinical trial protocol

Table 4: Reactogenicity and adverse events following pandemic LAIV candidates’ vaccination.

| Live attenuated vaccine for pandemic influenza |

No positive |

Virus was detected by |

Any antibody |

Any cell mediated |

Any immune |

Ref. |

| |

subjects |

PCR |

Culture |

response |

response |

response |

|

| 7:11 |

A/17/duck/Potsdam/86/92 (H5N2) |

n/N |

Nt2 |

14/20 |

16/20 |

5/10 |

16/20 |

[50,51,54] |

| |

|

% |

Nt |

70.0 |

80.0 |

50.0 |

80.0 |

|

| 7:1 |

A/17/turkey/Turkey/05/133 (H5N2) |

n/N |

28/29 |

14/29 |

23/29 |

20/29 |

25/29 |

[53] |

| |

|

% |

95.6 |

48.3 |

79.3 |

69.0 |

86.2 |

|

| 6:2 |

A/17/mallard/Netherlands/00/95 (H7N3) |

n/N |

17/29 |

4/29 |

24/29 |

12/29 |

28/29 |

[43] |

| |

|

% |

58.6 |

13.8 |

82.8 |

41.4 |

96.6 |

|

| 6:2 |

A/17/California/66/395 (H2N2) |

n/N |

21/27 |

13/27 |

23/27 |

15/27 |

25/27 |

[52] |

| |

|

% |

77.8 |

48.1 |

85.2 |

55.6 |

92.6 |

|

1Genomic composition.

2Not tested

Table 5: Cumulative data on vaccine virus shedding and immune responses to LAIV against potentially pandemic influenza viruses in vaccinated

subjects after the first and/or the second doses.

The first pandemic A/17/duck/Potsdam/86/92 (H5N2) LAIV Phase I clinical trial protocol included only a group of vaccinated volunteers [49]; placebo group was excluded at the recommendation of the Medical Ethics Committee. All the other Phase I clinical trials were randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled [43,52,53].

Safety

Clinical examination of volunteers who received two doses of pandemic LAIVs during Phase I clinical trials indicated that the vaccines were well tolerated (Table 4). No febrile reactions, no clinically significant adverse events or changes in metabolic and hematologic laboratory tests were observed after either the first or the second vaccination. The adverse events observed were limited to sore throat, fever, nasal congestion and catarrhal nasopharynx, sneezing and headache.

Vaccine virus shedding and genetic stability of LAIV isolates

The level of pandemic LAIVs’ shedding detected by culturing nasal swabs in embryonated chicken eggs varied from 13.8% (A/17/mallard/Netherlands/00/95) [43] to 70.0% (A/17/duck/ Potsdam/86/92) [51] (Table 5). All isolates were sequenced to assess the genetic stability of the vaccine virus after replication in humans. All clinical isolates were shown to preserve all attenuating mutations of the MDV. In addition, their ts/ca phenotype was tested. All isolates retained the vaccine phenotypic characteristics of cold adaptation and temperature sensitivity described for MDV [43,51-53].

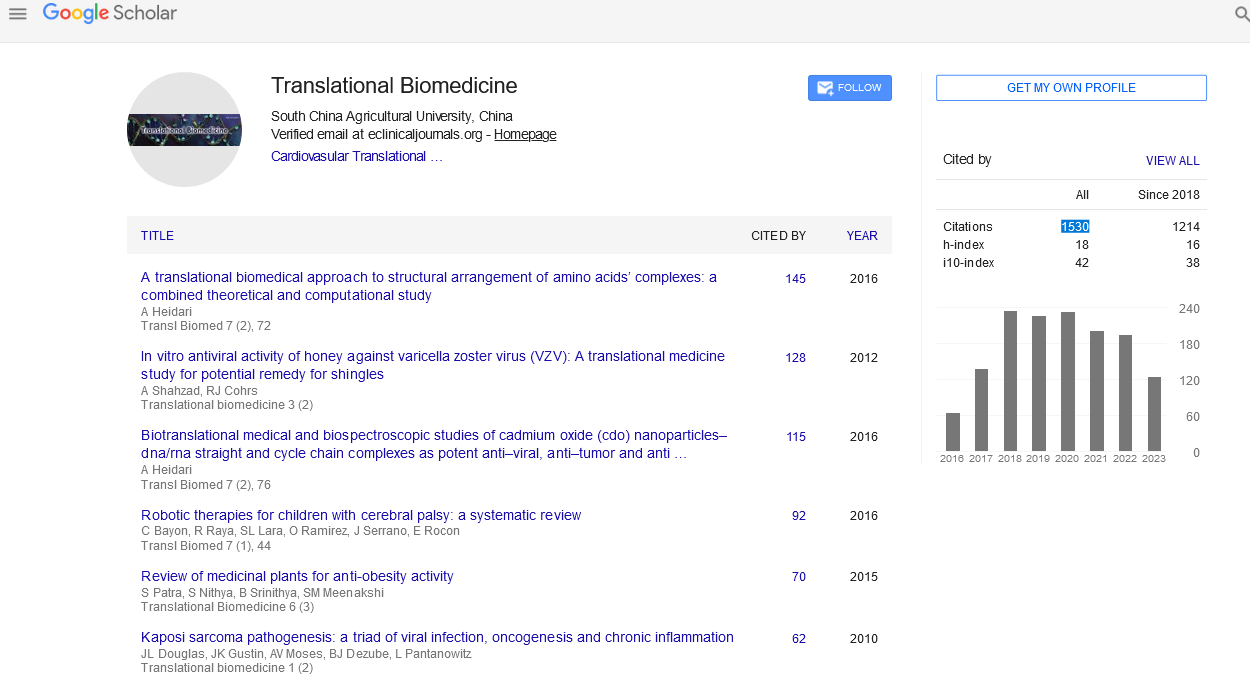

Immunogenicity

The immune responses to pandemic LAIVs have been extensively studied. Antibody immune responses were measured by routine hemagglutination inhibition and microneutralization tests; influenza virus-specific serum IgG and IgA antibodies, as well as local (mucosal) IgA antibodies in nasal secretions were tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Cellular immune responses were measured by a post-vaccination increase of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell levels by flow cytometry cytokine assay [54]. Two doses of pandemic LAIVs induced mucosal IgA, serum HAI, IgA and IgG, and neutralizing antibodies, as well as cell-mediated immune responses in healthy adults (Table 5). Cumulative percentage of subjects with any antibody and/or cell-mediated immune responses to pandemic LAIVs after the first and/or the second doses reached the value of 80.0-96.6% (Table 5).

Conclusion

Avian influenza viruses remain a major pandemic threat. During the development of Russian LAIV candidates against H5 HPAIVs two new methodological approaches have been employed: (i) the use of reverse genetically constructed H5N1 strains for inactivated vaccine as a source of HA and NA genes, and (ii) inactivation of wild type parental viruses by UV prior to co-infection with Len- MDV. The use of H5N1/PR8-RG reassortants instead of wild-type HPAIVs will minimize a risk to the laboratory personnel during the process of LAIV strain preparation, and also will significantly reduce virus pathogenicity to chick embryos.

The aim of the development of LAIV candidate is to create an attenuated virus comprised of two key antigenic determinants of circulating influenza viruses, HA and NA, and six internal protein genes of the MDV, which are responsible for attenuation [55].However, 7:1 reassortants carrying the RG-modified HA genes of H5N1 HPAIVs and the remaining genes from an attenuated MDV might be vaccine candidates of choice.

It is important to note that attenuated properties and immunogenicity of any LAIV candidate should be well balanced. After years of large-scale studies performed by researchers from all over the world, 6:2 genomic composition has been chosen as the best ratio of wild-type and attenuated genes in the genome of vaccine reassortants [55]. Nonetheless, HA and NA genes discordance in the genome of 7:1 pandemic vaccine candidates did not affect dramatically its immunogenic properties, as compared to those of 6:2 candidates.

In spite of differences in the genomic composition (6:2 or 7:1), all eight pandemic vaccine candidates expressed phenotypic characteristics described for MDV and MDV-based seasonal LAIVs - cold adaptation, temperature sensitivity and attenuation for different animal models.

Furthermore, Phase I clinical trials of two 6:2 LAIVs and two 7:1 LAIVs completed so far demonstrated their good safety and immunogenicity profiles. The 7:1 pandemic vaccine based on A/17/duck/Potsdam/86/92 strain was safe and immunogenic for adults and children and was registered in Russia as Ultragrivac? LAIV. The Phase I clinical trial of the fifth pandemic vaccine candidate, A/17/Anhui/2013/61 (H7N9), has been recently completed and preliminary observations indicate that the vaccine was also safe and immunogenic for healthy adults.

Overall, an LAIV virus bearing an RG-modified HA of a HPAIV and the remaining genes from the cold-adapted MDV has several potential advantages as a pandemic vaccine candidate. Selection of such high-yield viruses for vaccine manufacture is one of the advantages of using classical reassortment method; such highyield 7:1 LAIVs against HPAIVs will stimulate pronounced antibody and cell-mediated immune responses. This approach will allow timely production of sufficient amounts of LAIVs to meet the vaccine demand during a pandemic.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Oleg Kiselev, Marianna Erofeeva and Marina Stukova for the organizing and conducting clinical trials of pandemic LAIVs. The authors are very grateful to Ted Ross, David Swayne and Jorgen de Jonge for their participation in preclinical studies. We are thankful to Kathy Neuzil, Rick Bright, John Victor, Jorge Flores and Vadim Tsvetnitsky for the collaboration on the development, preclinical and clinical trials of pandemic LAIVs and to Microgen for the production of the vaccine clinical lots.

Competing Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Financial Disclosure

This work was funded by Russian Scientific Fund (RSF) No.14-15- 00034 (Moscow, Russia).

6751

References

- WHO (2007) Initiative for Vaccine Research (IVR). Options for live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) in the control of epidemic and pandemic influenza.

- WHO(2009) Global pandemic influenza action plan to increase vaccine supply: progress report. Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals, 2006-2008.

- Rudenko L, Arden N, Grigorieva E, Naychin A, Rekstin A, et al. (2000) Immunogenicity and efficacy of Russian live attenuated and US inactivated influenza vaccines used alone and in combination in nursing home residents. Vaccine 19:308-318.

- Glezen W (2004) Cold-adapted, live attenuated influenza vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines 3:131-139.

- Voeten JT, Kiseleva IV, Glansbeek HL, Basten SM, Drieszen-van derCSK, et al. (2010)Master donor viruses A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) and B/USSR/60/69 and derived reassortants used in live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) do not display neurovirulent properties in a mouse model. Arch Virol 155:1391-1399.

- Rudenko L, Van den Bosch H, Kiseleva I, Mironov A, Naikhin A, et al. (2011) Live attenuated pandemic influenza vaccine: clinical studies on A/17/California/2009/38 (H1N1) and licensing of the Russian-developed technology to WHO for pandemic influenza preparedness in developing countries. Vaccine 29 Suppl 1: A40-A44.

- Jin H, Subbarao K (2015) Live attenuated influenza vaccine. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 386:181-204.

- Horimoto T, Murakami S, Muramoto Y, Yamada S, Fujii K, et al. (2007)Enhanced growth of seed viruses for H5N1 influenza vaccines. Virology366:23-27.

- Kiseleva I, Larionova N, Fedorova E, Dubrovina I, BazhenovaE, et al. (2013) Live cold-adapted attenuated vaccine against H5N1 influenza viruses. Journal of Medical Safety July 2013:36-41.

- Clements ML, Subbarao EK, Fries LF, Karron RA, London WT, et al. (1992)Use of single-gene reassortant viruses to study the role of avian influenza A virus genes in attenuation of wild-type human influenza A virus for squirrel monkeys and adult human volunteers. J Clin Microbiol 30:655-662.

- Medvedeva TE,Gordon MA, Ghendon YZ,Klimov AI, Alexandrova GI (1983) Attenuated influenza B virus recombinants obtained by crossing of B/England/2608/76 virus with a cold-adapted B/Leningrad/14/17/55 strain. Acta Virol 27:311-317.

- Polezhaev FI, Garmashova LM, Polyakov YuM, Golubev DB, Aleksandrova GI (1978)Conditions for production of thermosensitive attenuated influenza virus recombinants. Acta Virol 22:263-269.

- Wareing MD, Marsh GA, Tannock GA (2002) Preparation and characterization of attenuated cold-adapted influenza A reassortants derived from the A/Leningrad/134/17/57 donor strain. Vaccine 20: 2082-2090.

- Kiseleva I, Larionova N, Fedorova E, BazhenovaE, Dubrovina I, et al. (2014) Contribution of neuraminidase of influenza viruses to the sensitivity to normal sera inhibitors and reassortment efficiency. Open Microbiol J 8:59-70.

- Baron S, Jensen KE (1955) Evidence for genetic interaction between non-infectious and infectious influenza A viruses. J Exp Med 102:677-697.

- Gotlieb T, Hirst GK (1956) The experimental production of combination forms of virus. VI. Reactivation of influenza viruses after inactivation by ultraviolet light. Virology 2:235-248.

- Larionova N, Kiseleva I, Dubrovina I, Bazhenova E, Rudenko L (2011)Peculiarities of reassortment of cold-adapted influenza A master donor virus with viruses possessed avian origin HA and NA H5N1. Influenza and other respiratory viruses 5 Suppl 1: 346-349.

- Rudneva IA, Timofeeva TA, Shilov AA, Kochergin-Nikitsky KS, Varich NL, et al. (2007) Effect of gene constellation and post-reassortment amino acid change on the phenotypic features of H5 influenza virus reassortants. Arch Virol 152:1139-1145.

- Cox NJ, Maassab HF, Kendal AP (1979) Comparative studies of wild-type and cold-mutant (temperature-sensitive) influenza viruses: nonrandom reassortment of genes during preparation of live virus vaccine candidates by recombination at 25°C between recent H3N2 and H1N1 epidemic strains and cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60. Virology 97:190-194.

- Polezhaev FI, Garmashova LM, Rumovsky VI, Aleksandrova GI, Smorodintsev AA (1980) Peculiarities of obtaining attenuated thermosensitive recombinants of influenza A virus at the end of the H3N2 cycle. Acta Virol 24:273-278.

- Kiseleva I, Youil R, Su Q, Toner T, Szymkowiak C, et al. (2004) Development and evaluation of live influenza (LIV) cold adapted reassortant vaccines in cell culture. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Options for the Control of Influenza V. Okinawa, Japan, 6-9 October, 2003. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 551-554.

- Kiseleva I, Sua Q, Toner TJ, Szymkowiak C, Kwan WS, et al. (2004) Cell-based assay for the determination of temperature sensitive and cold-adapted phenotypes of influenza viruses. J Virol Meth 116:71-78.

- Murphy BR, Hosier NT, Spring SB, Mostow SR, Chanock RM (1978) Temperature-sensitive mutants of influenza A virus: production and characterization of A/Victoria/3/75-ts-l[E] recombinants. Infect Immun 20:665-670.

- Murphy BR, Buckler-White AJ, London WT, Harper J, Tierney EL, et al. (1984) Avian-human reassortant influenza A viruses derived by mating avian and human influenza A viruses. J Infect Dis 150:841-850.

- Shu-Yi F, Tanaka T, Goto H, Tobita K (1983) Genetic recombination between temperature-sensitive and wild-type influenza A virus strains. Acta Virol 27:21-26.

- Burnet FM, Lind PE (1954) Reactivation of heat inactivated influenza virus by recombination. Austral J Exp Biol 32:133-144.

- Lind PE, Burnet FM (1957) Further studies of recombination between heat-inactivated virus and active virus. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci 35:531-540.

- Simpson RW, Hirst GK (1961) Genetic recombination among influenza viruses. I. Cross reactivation of plaque-forming capacity as a method for selecting recombinants from the progeny of crosses between influenza A strains. Virology 15:436-451.

- Rudenko LG, Kiseleva IV, Larionova NV, Grigorieva EP, Naikhin AN (2004) Analysis of some factors influencing immunogenicity of live cold-adapted reassortant influenza vaccines. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Options for the Control of Influenza V. Okinawa, Japan, 6-9 October, 2003. Amsterdam: Elsevier 542-546.

- Kiseleva I, Larionova N, Kuznetsov V, Rudenko L (2010) Phenotypic characteristics of novel swine-origin influenza A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) virus. Influenza and other respiratory viruses 4:1-5.

- Kiseleva IV, Larionova NV, Bazhenova EA, Fedorova EA, Dubrovina IA, et al. (2014) Contribution of neuraminidase of influenza viruses to the sensitivity to serum inhibitors and reassortment efficiency. Molecular Genetics Microbiology and Virology 29:130-138.

- Kiseleva IV, Bazhenova EA, Larionova NV, Fedorova EA, Dubrovina IA, et al. (2013) Peculiarity of reassortment of current wild type influenza viruses with master donor viruses for live influenza vaccine. Vopr Virusol 58: 26-31.

- Larionova N, Kiseleva I, Isakova-Sivak I, Rekstin A, Dubrovina I, et al. (2013) Live attenuated influenza vaccines against highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza: development and preclinical characterization. J Vaccines Vaccin 4:208.

- Desheva JA, Rudenko LG, Alexandrova GI, Lu X, Rekstin AR, et al. (2004) Reassortment between avian apathogenic and human attenuated cold-adapted viruses as an approach for preparing influenza pandemic vaccines. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Options for the Control of Influenza V. Okinawa, Japan, Amsterdam:Elsevier724-727.

- Subbarao K, Chen H, Swayne D, Mingay L, Fodor E, et al. (2003) Evaluation of a genetically modified reassortant H5N1 Influenza A virus vaccine candidate generated by plasmid-based reverse genetics. Virology 305:192-200.

- Air GM (2012) Influenza neuraminidase. Influenza Other Respi Viruses 6: 245-256.

- Castrucci MR, Kawaoka Y (1993) Biologic importance of neuraminidase stalk length in influenza A virus. J Virol 67: 759-764.

- Mitnaul LJ, Matrosovich MN, Castrucci MR, Tuzikov AB, Bovin NV, et al. (2000) Balanced hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activities are critical for efficient replication of influenza A virus. J Virol 74: 6015-6020.

- Murakami S, Horimoto T, Mai le Q, Nidom CA, Chen H, et al. (2008)Growth determinants for H5N1 influenza vaccine seed viruses in MDCK cells. J Virol 82:10502-10509.

- Desheva JA, Rudenko LG, Rekstin AR, David Swayne D, Cox NJ, et al. (2008) Development of candidate H7N3 live attenuated cold-adapted influenza vaccine. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Options for the Control of Influenza VI. Toronto, Canada, June 17-23, 2007. London: International Medical Press 591-592.

- Isakova SI, de JJ, Smolonogina T, Rekstin A, Amerongen VG et al. (2014) Development and pre-clinical evaluation of two LAIV strains against potentially pandemic H2N2 influenza virus. PLoS One 24 9:e102339.

- Rudenko L, Kiseleva I, Naykhin A, Erofeeva M, Stukova M, et al. (2014) Assessment of human immune responses to H7 avian influenza virus of pandemic potential: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized double-blind phase I study of live attenuated H7N3 influenza vaccine. PloS ONE 9: e87962.

- Klimov AI, Cox NJ, Yotov WV, Rocha E, Alexandrova GI, et al. (1992)Sequence changes in the live attenuated, cold-adapted variants of influenza A/Leningrad/134/57 (H2N2) virus. Virology 186:795-797.

- Klimov AI, Kiseleva IV, Alexandrova GI, Cox NJ (2001) Genes coding for polymerase proteins are essential for attenuation of the cold-adapted A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2) influenza virus. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Options for the Control of Influenza IV. Hersonissos, Crete, Greece, 23-28 September, 2000. Amsterdam: Elsevier955-959.

- Isakova SI, Chen LM, Matsuoka Y, Voeten JTM, Kiseleva I, et al. (2011) Genetic bases of the temperature-sensitive phenotype of a master donor virus used in live attenuated influenza vaccines: A/Leningrad/134/17/57 (H2N2). Virology 412:297-305.

- Desheva JA, Lu XH, Rekstin AR, Rudenko LG, Swayne DE, et al. (2006) Characterization of an influenza A H5N2 reassortant as a candidate for live-attenuated and inactivated vaccines against highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses with pandemic potential. Vaccine 24:6859-6686.

- Rekstin A, Desheva Y, Kiseleva I, Ross T, Swayne D, et al. (2014) Live attenuated influenza H7N3 vaccine is safe, immunogenic and confers protection in animal models. Open Microbiol J 8:154-162.

- Rudenko L,Desheva J, Korovkin S, Mironov A, Rekstin A, et al. (2008) Safety and immunogenicity of live attenuated influenza reassortant H5 vaccine (phase I-II clinical trials). Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2:203-109.

- Rudenko L, Kiseleva I, Mironov A, Desheva J, Larionova N, et al. (2011) Development of pandemic live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) in Russia. Influenza and other respiratory viruses 5. Suppl 1: 333-337.

- Rudenko L, Isakova SI (2015)Pandemic preparedness with live attenuated influenza vaccines based on A/Leningrad/134/17/57 master donor virus. Expert Rev Vaccines 14:395-412.

- Isakova SI, Stukova M, Erofeeva M, Naykhin A, Donina S, et al. (2015) H2N2 live attenuated influenza vaccine is safe and immunogenic for healthy adult volunteers. Hum Vaccin Immunother 11: 970-982.

- Rudenko L, Kiseleva I, Stukova M, Erofeeva M, Naykhin A, et al. (2015) Clinical testing of pre-pandemic live attenuated A/H5N2 influenza candidate vaccine in adult volunteers: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized double-blind phase I study. Vaccine.

- Chirkova TV, Naykhin AN, Petukhova GD, Korenkov DA, Donina SA, et al. (2011)Memory T-cell immune response in healthy young adults vaccinated with live attenuated influenza A (H5N2) vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:1710-1718.

- Expert Committee on Biological Standardization (2009) WHO recommendations to assure the quality, safety, and efficacy of influenza vaccines (human, live attenuated) for intranasal administration. Geneva.