Key words

Nurses, attitudes, attempted suicide, parasuicide, self-destructive behavior, self-poisoning

Introduction

The cases of suicide in Greece have increased dramatically according to National Statistic Office. [1] In particular, during the years 1999-2009, 4042 suicides were recorded in Greece. [1] Though there are not official statistics on attempted suicide in Greece both media as well as health care workers report that suicide attempts have increased considerably over the last five years. These reports are in line with data from Europe and United States. [2] Hospital admission for deliberate self - harm is 17 times more common than death due to suicide. [3] Attempted suicide, especially self-poisoning, is the most common reason patients admitted to a general hospital. [4]

Most previous studies of attitudes towards attempted suicide patients among health care professionals have presented that health care professionals have generally unfavorable attitudes towards self-poisoning. [5,6] In contrast, McCann et al., [2] found that nurses working in emergency departments had sympathetic attitudes towards patients who self-harm, including both professional and lay conceptualizations of deliberate self-harm. In addition, they found no discriminatory attitudes towards deliberately self-harming patients in nurses’ triage and care decisions. Notwithstanding, McAllister et al., [7] state that caring for people who present to emergency department because of deliberate self-harm often evokes strong emotions and negative attitudes in staff. A number of studies reported that emergency nurses experience a high degree of ambivalence, frustration, and distress about self-harming patients. [8,9,10] In addition, self-harm clients may evoke negative attitudes such as anxiety, anger, and an absence of empathy. [7] However, Boyes [11] argued that staff reported frustration at their inability to “cure” the patient. According to Vivekananda [12] staff may tend to distance themselves from such clients rationalizing that the person is manipulative, attention seeking or cannot be helped.

Happell et al., [13] state that emergency and triage nurses are pivotal in detecting deliberate self-harm patients and prioritizing their care, but many believe they are not well prepared to assess patients with mental health problems. This lack of confidence influences the negative attitudes nurses hold towards deliberate self-harm patients and results in nurses giving low priority to these patients. [13,14] Suokas and Lonnqvist [15], compared emergency department nursing staff attitudes to self-harming clients with intensive care staff and found that emergency nursing staff to be more negative towards these clients than the intensive care staff.

McCann et al., [2] referring to other authors, point out that health care professionals may feel ambivalent towards patients who self-harm [16], sometimes perceiving them as troublesome [17] or attention-seeking. [18] They do not understand why patients harm themselves and they doubt if nurses have the necessary skills to care for this group of individuals. [18,19] Sometimes emergency nurses believe that patients who self-harm should be cared for by mental health professionals. Sanders [20] in a systematic review of health care professional attitudes and patients’ perceptions of “inappropriate” emergency department attendances found that negative attitudes lead to a reduction in care from nurses, who found this work time-consuming and unrewarding. The negative attitudes of health care professionals towards attempted suicide have been confirmed by patients’ perception of care in emergency departments. [2] Nevertheless, a few studies found nurses holding largely positive attitudes towards patients who attempted suicide through overdose. [21]

Sun et al., [22] carried out a study to investigate casualty nurses’ attitudes towards to patients who have attempted suicide and to identify the factors contributing to those attitudes. They found that casualty nurses held positive attitudes toward patients who have attempted suicide. In addition, they identified statistical significant differences with respect to nurses with higher level of nursing education which held more positive attitudes. Moreover, the casualty nurses who did not have a religion held statistically significant more positive attitudes towards attempted suicide than those who followed a religion. Furthermore, casualty nurses who had care experience with 1-10 attempted suicide patients had more positive attitudes towards suicidal patients than nurses who had nursed over 10 patients who had attempted suicide.

A number of studies have investigated the influence of age and clinical experience on nurses’ attitudes; however, the results are not conclusive. [2] Junior nurses hold more negative attitudes towards self-poisoning patients and express less willingness to help and this negative response is associated with increased level of contact with suicidal patients. [23] In contrast to the above results, studies carried out to explore the attitudes of emergency nurses found that older and more experienced nurses held more favorable attitudes than younger and less experienced. [21,24] Nevertheless, a study carried out in an emergency department in Queensland, Australia, found no significant relationships between duration of clinical experience and attitudes to self-harm. [7]

Given that globally there is an increasing rate of suicide and attempted suicide it is apparent that the nursing staff’s work in this area is increasing. Whitworth [25] supports that caring for attempted suicide patients causes possibly stress to health care professionals, in addition to other negative feelings such as anxiety, irritation, lack of empathy and fear.

The negative feelings that the nursing staff hold in combination with the stigma attached to suicide and attempted suicide result negative attitudes towards attempted suicide patients emerging.

It worth stressing that nearly one third of patients admitted to general hospitals following self-poisoning suicide attempts will be readmitted for subsequent similar acts on future occasions. [26] Suicide risk after deliberate self-harm is 50 times greater than in the general population. [18]

Health care professionals working in the general hospital have a key role to play in the prevention of repeated episode of attempted suicide, as it is likely that the type and quality of care and treatment provided will influence subsequent client outcomes. [27] In addition, it has been reported that suicide attempts increase the risk of suicidal behavior showing the necessity for appropriate interventions for minimizing the risk of self-destructive behavior. [28] Clinicians need to respond to deliberate self-harm appropriately, as the relationship between deliberate self-harm and suicide is well established. [29]

McCann et al., [2] cite that several studies have reported attempts to improve nurses’ attitudes towards self-harm, as negative attitudes towards attempted suicide patients may affect the quality of care they provide. [27,30] In particular, education has been found to improve negative attitudes [31,32] as well as improve the standards of psychosocial assessment of patients presenting to emergency departments with deliberate self-harm actions. [14,33]

Sun et al., [22] conclude that nurses’ attitudes towards suicidal patients are worthy of exploration due to the fact that this type of research could have an impact on nurses’ self-awareness of the important role they play in the provision of effective care. Moreover, nurses’ response of rejection or hostility may prompt patients’ further suicidal behavior. [10]

Therefore, it is important to investigate nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide in Greece because the majority of the relevant studies have been carried out in UK, United States and Scandinavian countries.

Methodology

Definition of term

Nurses: for the purpose of the present research as nurses considered both registered and assistant nurses.

The main aim of the study was to explore nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide patients.

Objectives

1st To explore respondents’ feelings in response to the hospitalization of attempted suicide patients.

2nd To identify if independent variables such as demographic variables, professional characteristics, level of education, postgraduate studies, would have an influence on nursing’s staff attitudes towards attempted suicide patients.

3rd To identify if other variables such as respondents’ personal acquaintance with a person who committed suicide, would have an impact on nursing staff’s attitudes.

4th To identify possibly different attitudes of nurses’, working in several specialties towards attempted suicide patients.

5th To identify predictive variables which form nurses’ positive attitudes towards attempted suicide.

Research design

In order to achieve the aim and the objectives of the study a cross-sectional research design utilised. The variables investigated in the study were distinguished as independent and dependent variables.

Sample and research site

Data were collected from a convenience sample of registered and assistant nurses working in medical, surgical, orthopedic, intensive care units (ICU) as well accident and emergency departments of four general hospitals in Greece. Participation in the study was voluntary. One of the criteria for the inclusion of subjects was to have direct contact or direct involvement with attempted suicide patients’ care. Therefore, questionnaires distributed to nursing staff and not to the level of ward manager.

Ethical issues

The directors of nursing services of the four hospitals approved this study. Nursing staff who were interested in participating were reassured of anonymity of responses as well as for their right to withdraw at any time. Implied consent to participate was assumed by completion and return of the questionnaire.

Instrument

Data were collected using the likert type questionnaire “Attitudes Towards Attempted Suicide-Questionnaire” (ATAS-Q) [34] developed in another study to assess doctors’ and nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide. The ATAS-Q comprises 80 items measuring health care professionals’ attitudes towards attempted suicide. The questionnaire consists of 8 factors (F1 “positiveness”, F2 “acceptability”, F3 “religiosity”, F4 “professional role and care”, F5 “manipulation”, F6 “personality traits”, F7 “mental illness”, F8 “discrimination”) and each factor reflects different attitudinal aspects. The questionnaire was likert type (1=strongly disagree, 2= disagree, 3= undecided, 4=agree and with 5=strongly agree). The possible score ranges from 80 (which reflects the most negative attitudes) to 400 (which reflects the most positive attitudes towards attempted suicide). Two independent researchers were requested to assess the validity of the questionnaire and reported that it has high content and face validity. The scale presented high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha a=0.97. [27] In addition, after the completion of the study when internal consistency was assessed Cronbach’s alpha was a=0.86 which is satisfactory.

Moreover, the questionnaire also recorded demographic variables such as nurses’ professional and personal characteristics (length of professional experience, department of work, specialization in nursing, postgraduate studies, respondents’ level of religiosity, any personal suicidal thought and respondents’ experience of having known someone who had committed suicide).

Data analysis

Data collected were analysed using SPSS version 17. Descriptive and inferential statistics were utilized to analyze the data. With respect to the scale measuring nursing staff’s attitudes towards attempted suicide the mean and standard deviation for each of the 8 factors of the scale were established as well as the total score of the scale. In addition, one way Analysis of Variance was used in order to identify statistical significant differences between the independent variables in relation to the dependent variable “attitudes towards attempted suicide” which measured with ATAS-Q. Multiple regression analysis was used to identify predictors of nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide patients. The acceptable level of statistical significance was the P≤ 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic

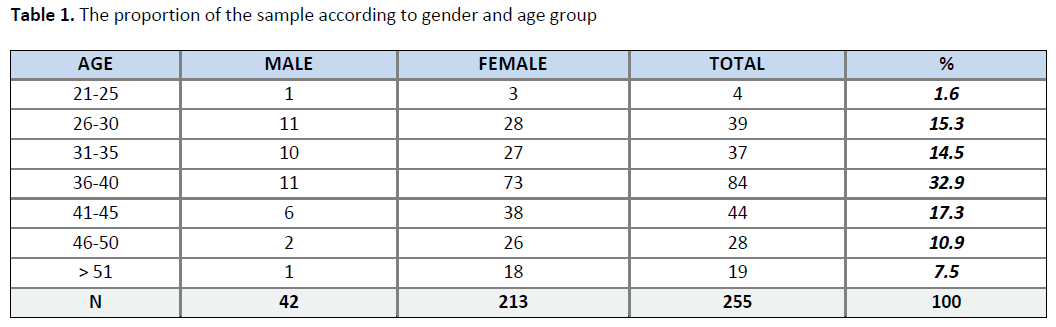

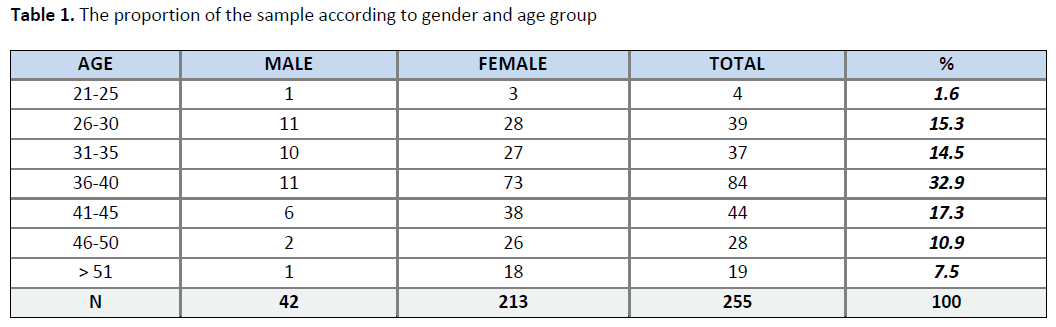

Two hundred fifty five (N=255) nursing staff participated in the present study. Overall response rate was 68%. Of the respondents 83.5% (n=213) were female and 16.5 (n=42) were male. The vast majority of the respondents were over thirty years old (Table 1).

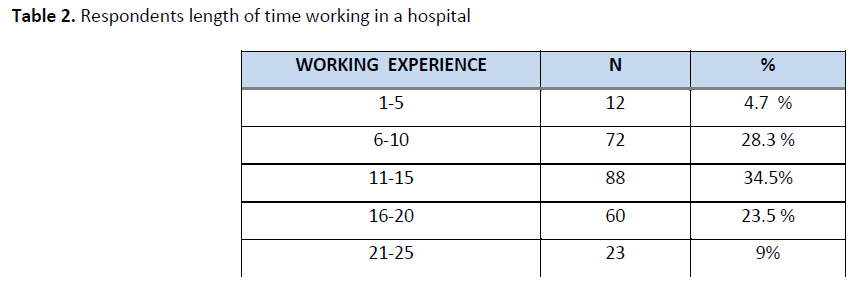

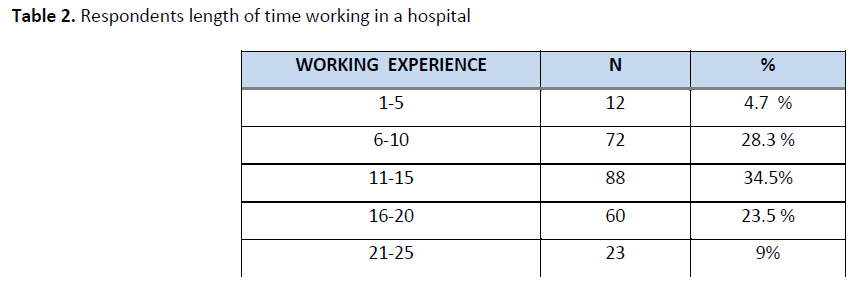

Nearly two third of the participants have been working as staff nurses between 6 and 15 years (Table 2). Of the participants 34.5% had 11-15 years working experience, 28.3% 6-10 years, 23.5% 16-20 years, 9% 21-25 years and 4.7% 1-5 years working experience (Table 2).

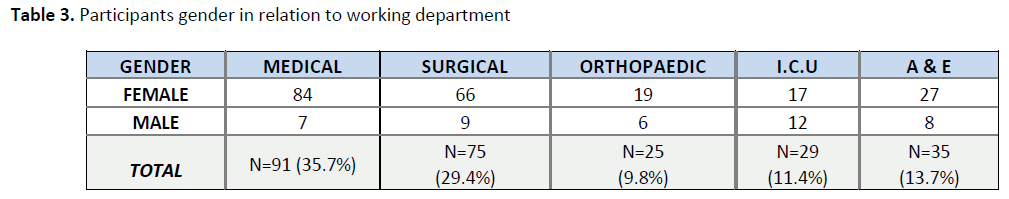

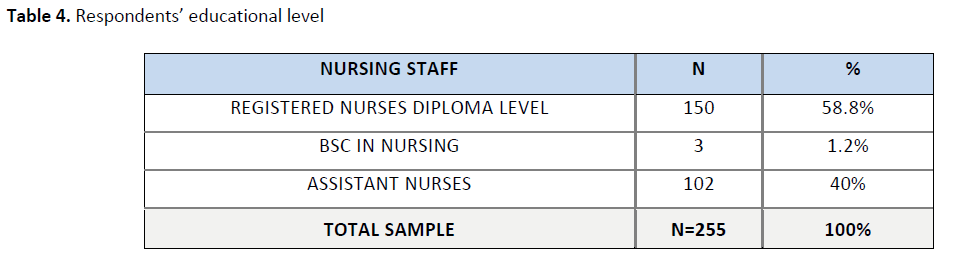

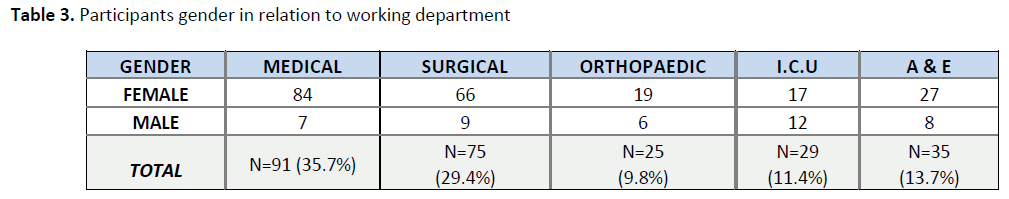

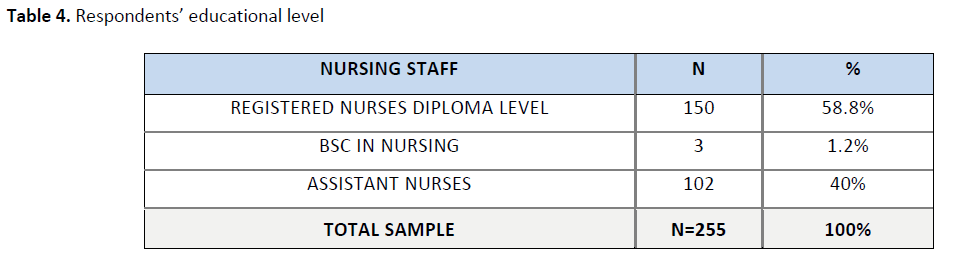

Over a quarter (35.7%) of the respondents worked in medical wards and were female. Similarly, 29.4% of the participants were female and worked in surgical wards. Less proportion of the sample worked in orthopaedic, ICU, or the accident and emergency department (Table 3). 58% of participants were registered nurses at diploma level, 1.2% held a BSc in Nursing and 40% were assistant nurses (Table 4).

Of the participants 23.5% held a specialization in nursing (medical or surgical) and a very small proportion (3.9%) had completed a master degree in nursing (Table 5).

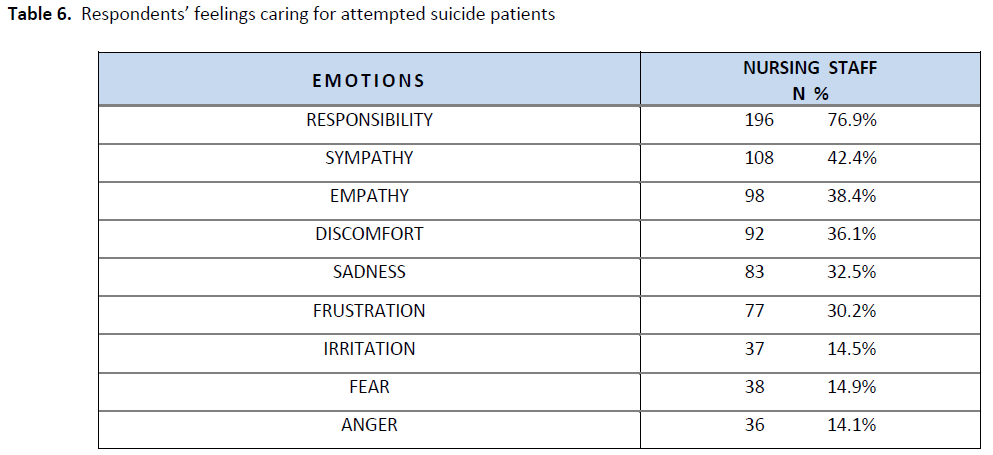

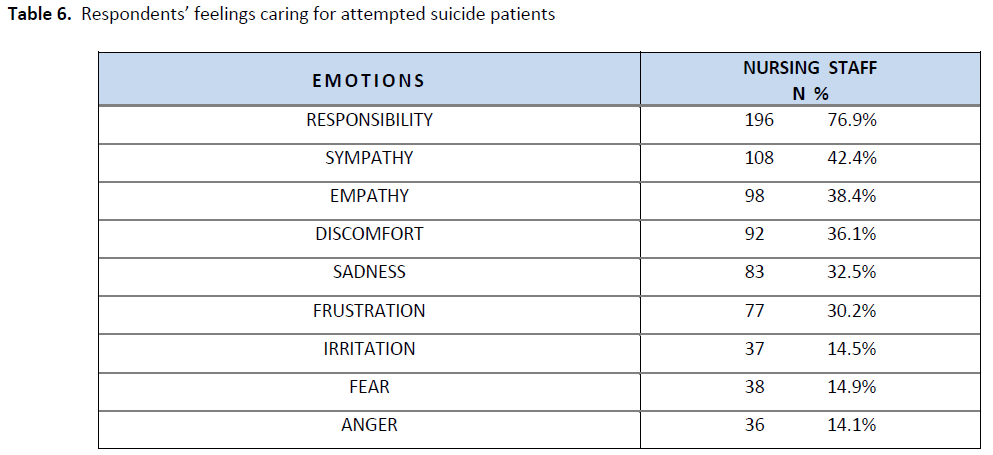

Table 6 illustrates participants’ feelings when caring for an attempted suicide patient. Respondents described that they experienced a variety of feelings in response to the hospitalization of attempted suicide patients. Such feelings were responsibility (76.9%), sympathy (42.4%), empathy (38.4%), discomfort (36.1%), sadness (32.5%), frustration (30.2%), irritation (14.5%), fear (14.9%) whereas the smallest proportion reported anger (14.1%).

Attitudes towards attempted suicide

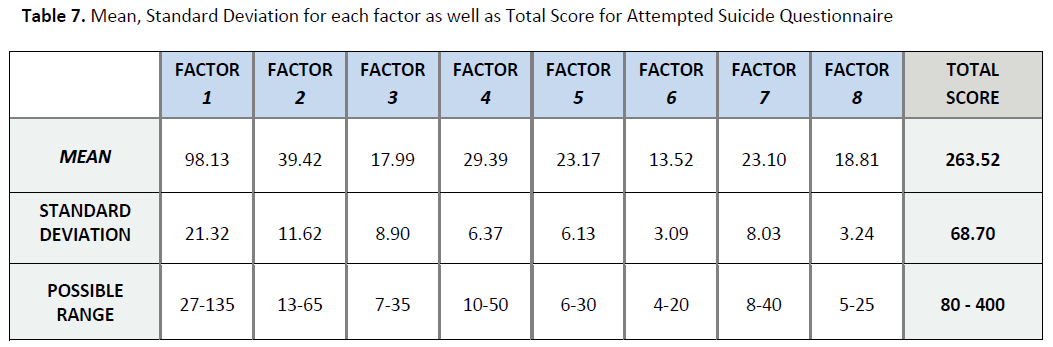

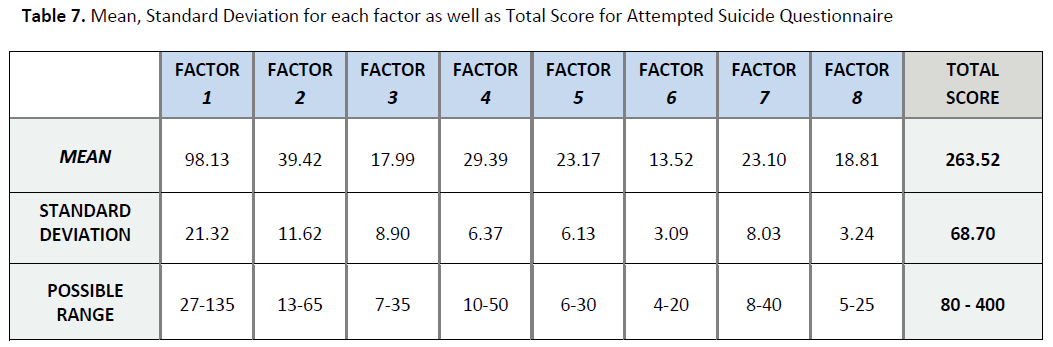

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that respondents held relatively unfavorable attitudes towards attempted suicide (M=263.52; SD=68.70) as illustrated in table 7. However, the mean score of the 1st factor “positiveness” reflects respondents’ positive attitudes towards attempted suicide. The mean score of factor 2 “acceptability” might reflect participants’ neutrality towards people who attempt to suicide. Similarly, the mean score of the 3rd factor “religiosity” reflects participants’ neutral affect in forming attitudes towards attempted suicide people. Factor 4th “professional role and care” reflects participants views of the care that attempted suicide patients receive as well as the professional role and work environment of nursing staff. The mean score shows that people who attempt to suicide are treated in a neutral environment. With respect to factor 5th “manipulation” the mean score shows that respondents consider attempted suicide people as relatively manipulative. The mean score of the 6th factor “personality traits” shows that respondents hold relatively favorable views on attempted suicide people’s personality traits. The relatively low mean score of factor 7th “mental illness” reflects participants’ views that the act of attempting suicide is related to mental illness. The mean score of the 8th factor “discrimination” reflects positive disposition to attempted suicide people with nurses demonstrating very low levels of discrimination to those people (Table 7).

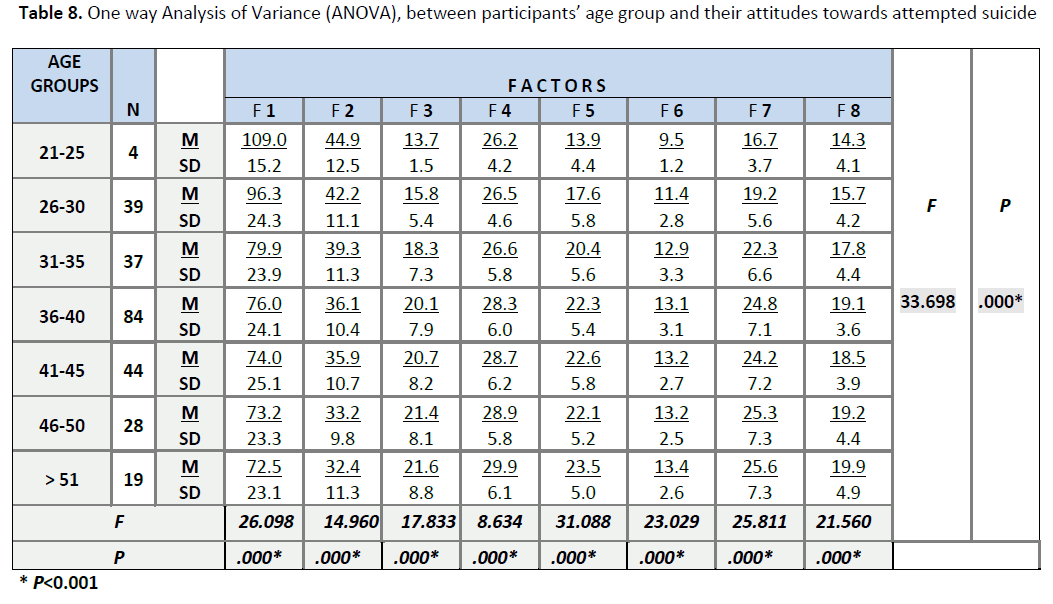

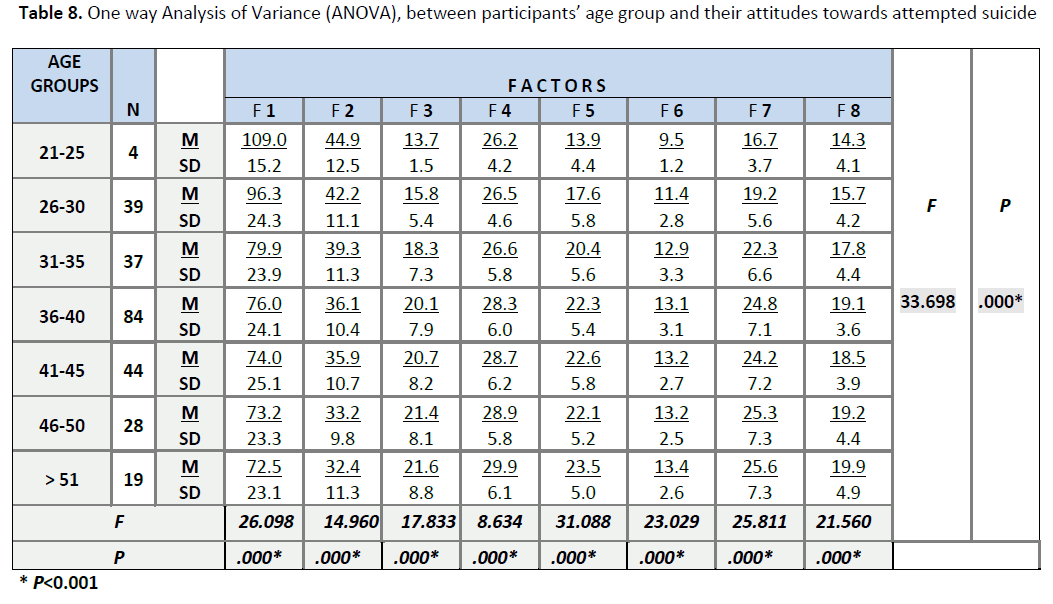

One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) between gender and ATAS-Q showed that women had more positive attitudes towards attempted suicide compared to men, however this difference was not at a statistically significant level (P= .218). Table 8 illustrates that the most favourable attitudes towards attempted suicide were held by those in the age group 21-25 years old. In addition, it shows that the older nurses held less positive attitudes.

In regard to nursing department and nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide the results show that the most positive attitudes were held by nurses working in surgical wards and in sequence in orthopedic, medical, A&E and the most unfavourable attitudes were held in ICU (Table 9). In addition, table 9 shows the nurses’ attitudes from different nursing departments towards the other factors of the ATAS-Q. [27]

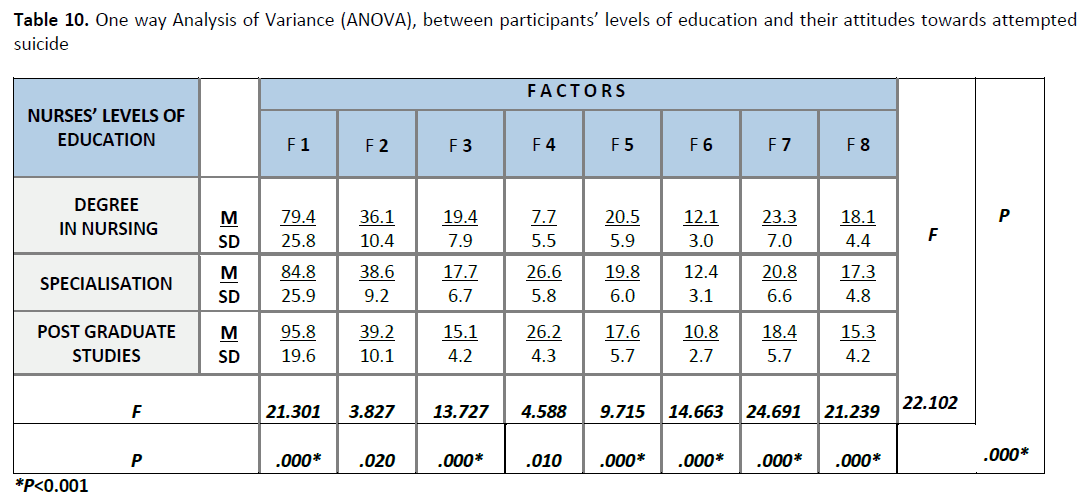

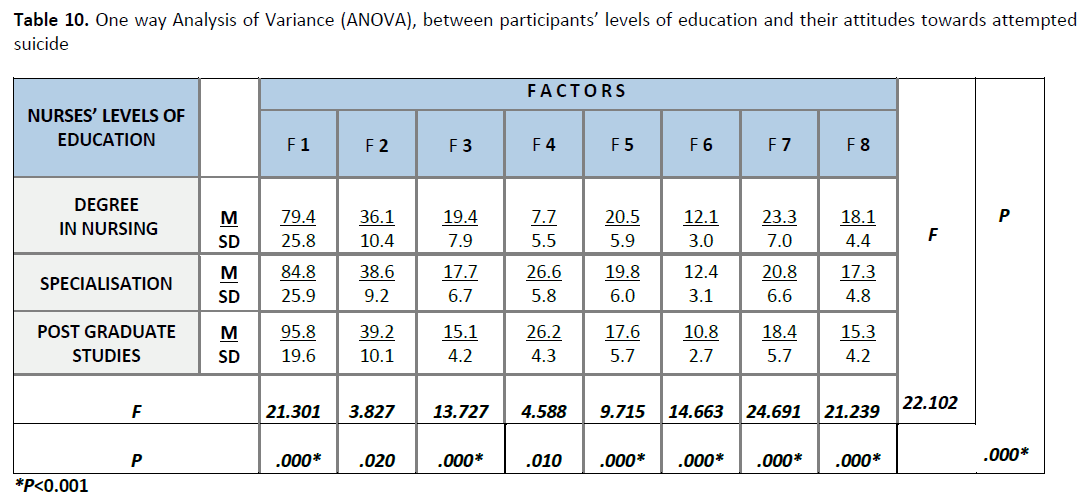

Nurses who had a master degree and specialization in nursing held statistically significant more positive attitudes towards attempted suicide patients.

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) between attitude and respondents who reported that they had contemplated suicide once in their life, revealed that these nurses’ reported that they held statistically significant more positive attitudes compared to those reported that they had never contemplated suicide (F=103.769; P=0.001). In addition, respondents’ who had had a relationship with a person who had committed suicide reported statistically significant more positive attitudes (F=102.689; P=0.001) towards patients who had attempted suicide.

Multiple regression analysis found that predictive factors at statistically significant level (R2 0.389; P=001) for nurses’ favorable attitudes towards attempted suicide was nurses’ younger age, nurses working in orthopedic and in a surgical department, and having undertaken further studies mostly postgraduate studies as well as nursing specialization and nurses’ who had contemplated suicide.

Discussion

Overall respondents displayed relatively unfavorable attitudes towards attempted suicide which is in congruence with other studies carried out in different countries. [5,6-10] Though in the first factor “positiveness” nurses’ scored relatively high, this might reflect their professional attitude to treat all patients equally and not their attitudes towards attempted suicide. In addition, this discrepancy supports the fact that attitudes towards attempted suicide is a complex phenomenon and there is not just positive or negative. There are other mediating variables that influence nurses’ attitudes towards that group of patients. In contrary to the findings of the present study McCann et al., [2] found that nurses working in emergency departments had sympathetic, positive attitudes towards patients who self-harm. [22] In addition, they found no discriminatory attitudes towards patients who deliberately self-harm. However, some authors found nurses did not understand why patients harm themselves and doubted that they had the skills needed to care for this group of individuals. [18,19] Within this logic it was believed that patients who self-harmed should be cared for by mental health professionals [20]. However, the lack of confidence of nursing staff to treat self-harm individuals influence the negative attitudes nurses hold towards deliberate self-harm and led nurses to give low priority to these patients. [13,14]

With respect to the factor “acceptability” respondents’ displayed relatively neutral attitudes towards attempted suicide. It seems in the literature that nurses hold more positive attitudes towards those who took an overdose to attempt suicide. [21]

In regard to participants’ influence of “religiosity” in forming attitudes towards attempted suicide the mean score suggests that it doesn’t affect their attitudes. Similarly, participants’ professional role and working environment doesn’t play an influential role in forming a strong negative or positive attitude. Surprisingly in the factor “manipulation’ nurses showed that they don’t believe that attempted suicide people are manipulative. Eskin [35] states that people who attempt suicide to manipulate others may prompt negative reactions to themselves and others like them. However, a professional role of nurses is to avoid being judgmental and participants in the present study display such a professional profile. This can be confirmed by the feelings experienced by participants when caring for attempted suicide patients. The majority reported feelings of responsibility, sympathy and empathy for attempted suicide.

In respect to attempted suicide and personality traits, participants displayed neutral attitudes towards this group of patients. In contrast, participants considered attempted suicide as people with mental health problems. The relationship between attempt suicide and mental illness reflects Greek nurses’ social norms rather than their professional knowledge. Nurses’ professional behaviour is also reflected by the fact that in factor “discrimination” they showed that they don’t discriminate against attempted suicide patients. Similar finding were presented in McCann et al’s [2] study in which nurses working in accident and emergency department were found not to discriminate against self-harm patients.

It is noteworthy that participants expressed a variety of feelings equally positive and negative towards attempted suicide which shows ambivalent emotions towards these people. This result can justify the contradictory findings, from one part nurses overall reported relatively negative attitudes towards attempted suicide whereas, in the factor “positiveness” they displayed favorable attitudes towards attempted suicide. It has to be stressed that the majority of the studies avoided addressing emotional reactions of care-givers to attempted suicide or suicidal patients [36]. However, a number of studies reported that nurses experienced ambivalence, frustration, and distress with the specific group of self-harming patients. [8,9,10]

Of the variables tested gender was found to influence nurses’ attitudes with women holding more positive attitudes compared to men, however this difference was not at an acceptable statistically significant level. The finding that women are more positive about suicide and suicidal individuals is in agreement with other studies. [36,37] In contrast to the above finding, respondents age and years of experience in a hospital settings showed statistical significant (p=0.001) influence on attitudes. In particular, respondents who were younger and had less working experience held more positive attitudes compared to older and more experienced nurse. It seems that younger nurses directly involved with attempted suicide care are more empathetic, and potentially more enthusiastic with their work, less tired or burnt out compared to older nurses who had been repeatedly caring for attempted suicide patients in busy nursing wards for many years. The above finding was congruent with a study exploring the therapeutic and non therapeutic reactions in a group of nurses and doctors in Turkey to patients who have attempted suicide. [36]

Participants working in medical wards held the most favourable attitudes towards attempted suicide apparently because they treat attempted suicide, mostly overdose, without the need of intensive care. Besides, most of the nursing or medical interventions have already been performed by A&E nursing and medical staff who are the front line personnel. In sequence, respondents working in surgical and orthopaedic wards displayed favorable attitudes compared to other units. It seems that the specialization of the nursing department influences nurses’ attitudes, apparently due to the fact that surgical wards rarely treat attempted suicide so have less possibility to face difficulties with them. The fact that orthopaedic nurses also held positive attitudes may relate to the fact that attempters often choose falls as a mean to commit suicide and nurses may feel sympathy towards those patients and the very difficult situation that they experience after a fall. The most negative attitudes were expressed by respondents in intensive care units, then in accident and emergency departments. It is self-evident that nurses working in accident and emergency departments are in the front line, with a high level of workload and pressure to manage critical cases of patients. The fact that attempt suicide is a self-destructive behaviour and it not caused by either accident or independent physical cause might evoke negative feelings in nurses towards these patients. Similarly, in intensive care units the number of beds are limited world while and staff may find themselves expected to transfer critically ill patients who did not deliberately cause their critical condition. In contrast to the present finding emergency nursing staff held more negative attitudes towards self-harming patients compared to nursing staff working in an intensive care unit. [15]

However, attitudes can affect care decisions and negative attitudes, of which the nurse is unaware, could jeopardize patients’ best care and safety. Thus, it is vital to improve the educational preparation of emergency department nurses and intensive care units nurses for improving awareness, promoting the implementation of practice guidelines, and for improving attitudes towards patients attempted suicide. [2]

Nursing specialization title and postgraduate studies were found to have positive influences on respondents’ attitudes. Nevertheless, postgraduate studies were found to have more influence on forming respondents’ favourable attitudes. The higher level of nursing education has been found to positively influence nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide. [22] In addition, other factors were found to influence nurses’ attitudes; especially, nurses who had previously contemplated suicide, or had had a relationship with a person who had committed suicide reported more positive attitudes towards patients who had attempted suicide. This finding is in line with a study carried out in nurses and doctors in Turkey. [36] Moreover, predictive variable of positive attitudes towards attempted suicide were found specialization in nursing, postgraduate studies and a younger age of nurses.

Limitation of the study

This study illustrated the spectrum of attitudes that nurses hold in the sites that the study carried out. The cross-sectional research design used restricts the generalisability of the findings. However, the value of the findings is that the results illustrate that attitudes towards attempted suicide are complex and there is more than one factor which formulates a favorable or unfavorable attitudes towards them.

Conclusions

Nurses held relatively unfavorable attitudes towards attempted suicide. These attitudes are related to the feelings that nurses hold to these patients, the low educational level, the social norms that influence these attitudes as well as the context that nurses work in their working clinical environment. In contrast, high educational level accompanied by lifelong learning processes, the experience of having contemplated suicide or having had a relationship with a person who committed suicide, the younger age and the less work experience produced more favorable attitudes towards attempted suicide. Therefore, it is vital for nurses to transform their attitudes through training, reflection and clinical supervision in order to be more favorable and therapeutic towards attempted suicide patients, helping them to eliminate the potential of a future attempt to suicide.

References

- www.statistics.gr (accessed 28/03/2009)

- McCann TV, Clark E, McConnachie S, Harvey I. Deliberate self-harm; emergency department nurses’ attitudes. Triage and care intentions. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2007; 16(9):1704-1711.

- Calof DL. Chronic self–injury and self-mutilation in Adult Survivors of Incest and chilhood sexual Abuse: Aetiology, Assessment and Intervention. Family Psychotherapy Practice of Seatle, Washington, 1994.

- McKinlay A, Couston M, Cowan S. Nurses’ behavioural intentions towards self-poisoning patients: a theory of reasoned action, comparison of attitudes and subjective norms as predictive variables. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2001; 34 (1):107-116.

- O’Brien SEM, Stoll KA. Attitudes of medical and nursing staff towards self-poisoning patients in a London Hospital. International Journal of Nursing Studies 1977; 14(1):29-33.

- Leu SJ. Nurses Attitudes and difficulties in nursing interventions towards suicidal behavior in emergency department. Unpublished MSc Dissertation. The Kaohsiung Medical College, Taiwan, 2002.

- McAllister M, Creedy D, Moyle W, Farrugia C. Nurses’ attitudes towards clients who self-harm. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2002; 40(5): 578-586.

- Alston M, Robinson B. Nurses attitudes towards suicide. Omega 1992; 25(3):205-215.

- Palmer S. Parasuicide: a cause for concern. Nursing Standard 1993; 7(19):37-39.

- Hemmings A. Attitudes to deliberate self-harm among staff in an accident and emergency team. Mental Health Care 1999; 2(9):300-302.

- Boyes A. Repetition of overdose: a retrospective five year study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1994; 20(3):462-468.

- Vivekananda K. Integrating models for understanding self-injury. Psychotherapy in Australia 2000; 7(1): 18-25.

- Happell B, Summers M, Pinikahama J. Measuring the effectiveness of the national Mental Health Triage Scale in an Emergency department. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 2003; 12(4):288-292.

- McDonough S, Wynaden D, Finn M, McGowan S, Chapman R, Gray S. Emergency department mental health triage and consultancy service: an advanced practice role for mental health nurses. Contemporary Nurse 2003; 14(2):138-144.

- Suokas J, Lonnqvist J. Work stress has negative effects on the attitudes of emergency personnel towards patients who attempt suicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1989; 79(5):474-480.

- Holland J, Plumb M. The management of the serious suicide attempt: a special ICU problem. Heart and Lung 1973; 2(3):376-381.

- Davidhizar R. The management of the suicide patient in a critical care unit. Journal of Nursing Management 1993; 1(2):95-102.

- Dower J, Donald M, Kelly B, Raphael B. Pathways of care for young people who present for non-fatal deliberate self-harm. Centre for Primary Health care, University of Queensland, Brisbane, 2000.

- Hopkins C. ‘But what about the really ill, poorly people? (An ethnographic study into what it means to nurses in medical admission units to have people who have harmed themselves as their patients). Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2002; 9(2):147-154.

- Sansers J. A review of health professional attitudes and patients perceptions on “inappropriate” accident and emergency attendances. The implications for current minor injury services provision in England and Wales. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2000; 31(5):1097-1105.

- Mc Laughlin C. Casualty nurses' attitudes to attempted suicide. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1994; 2 (22): 1111-1118.

- Sun F, Long A, Boore J. The attitudes of casualty nurses in Taiwan to patients who have attempted suicide. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2007; 16(2): 255-263.

- Ghodse AH. The attitudes of casualty staff and ambulance personnel towards patients who take drugs. Social Science and Medicine 1978; 12(5A):341-346.

- Anderson M. Nurses' attitudes towards suicidal behaviour- a comparative study of community mental health nurses and nurses working in an accident and emergency department. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1997; 25(6):1283-1291.

- Whitworth RA. Is your patient Suicidal? Canadian Nurse 1984; 80(6): 40-42.

- Hall D, O’Brien F, Stark C, Pelosi A, Smith H. Thirteen year follow up of deliberate self-harm, using linked date. British Journal of Psychiatry 1998; 172:239-242.

- Hawton K, Marsack P, Fagg J. The attitudes of psychiatrists to deliberate self-poisoning: comparison with physicians and nurses. British Journal of Medical Psychology 1981; 54(1):341-348.

- Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry 2002; 181:193-199.

- Beck AT, Kovacs M. Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicidal intention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1979; 47(2):343-352.

- Rayner GC, Allen SL, Hohnson M. Countertransference and self-injury: a cognitive behavioral cycle. Journal of Advanced nursing 2005; 50(1):12-19.

- Morgan HG, Evans M, Johnson C, Stanton R. Can a lecture influence attitudes to suicide prevention? Journal of Research in Social Medicine 1996; 89(2):87-90.

- Samuelsson M, Asberg M. Training program in suicide prevention for psychiatric nursing personnel enhance attitudes to attempted suicide patients. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2002; 39(1):115-121.

- Crawford MJ, Turnbull G, Wessley S. Deliberate self-harm assessment by accidents and emergency staff: an intervention study. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine 1998; 15(1):18-22.

- Ouzouni Chr. and Nakakis K. Attitudes towards attempted suicide: the development of a measurement tool. Health Science Journal 2009; 3 (4):222-231.

- Eskin M. The effects of religious versus secular education on suicide ideation and suicidal attitudes in adolescent in Turkey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2004; 39(7):536-542.

- Demirkiran F, Eskin M. Therapeutic and nontherapeutic reactions in a group of nurses and doctors in Turkey to patients who have attempted suicide. Social Behavior and Personality 2006; 34 (8):891-905.

- Eskin M. Cross-Cultural tests of the gender-role consistency and stigma hypotheses of suicidal behavior. Journal of Gender, Culture and Health 1997; 2:245-262.

3054

References

- McCann TV, Clark E, McConnachie S, Harvey I. Deliberate self-harm; emergency department nurses’ attitudes. Triage and care intentions. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2007; 16(9):1704-1711.

- Calof DL. Chronic self–injury and self-mutilation in Adult Survivors of Incest and chilhood sexual Abuse: Aetiology, Assessment and Intervention. Family Psychotherapy Practice of Seatle, Washington, 1994.

- McKinlay A, Couston M, Cowan S. Nurses’ behavioural intentions towards self-poisoning patients: a theory of reasoned action, comparison of attitudes and subjective norms as predictive variables. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2001; 34 (1):107-116.

- O’Brien SEM, Stoll KA. Attitudes of medical and nursing staff towards self-poisoning patients in a London Hospital. International Journal of Nursing Studies 1977; 14(1):29-33.

- Leu SJ. Nurses Attitudes and difficulties in nursing interventions towards suicidal behavior in emergency department. Unpublished MSc Dissertation. The Kaohsiung Medical College, Taiwan, 2002.

- McAllister M, Creedy D, Moyle W, Farrugia C. Nurses’ attitudes towards clients who self-harm. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2002; 40(5): 578-586.

- Alston M, Robinson B. Nurses attitudes towards suicide. Omega 1992; 25(3):205-215.

- Palmer S. Parasuicide: a cause for concern. Nursing Standard 1993; 7(19):37-39.

- Hemmings A. Attitudes to deliberate self-harm among staff in an accident and emergency team. Mental Health Care 1999; 2(9):300-302.

- Boyes A. Repetition of overdose: a retrospective five year study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1994; 20(3):462-468.

- Vivekananda K. Integrating models for understanding self-injury. Psychotherapy in Australia 2000; 7(1): 18-25.

- Happell B, Summers M, Pinikahama J. Measuring the effectiveness of the national Mental Health Triage Scale in an Emergency department. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 2003; 12(4):288-292.

- McDonough S, Wynaden D, Finn M, McGowan S, Chapman R, Gray S. Emergency department mental health triage and consultancy service: an advanced practice role for mental health nurses. Contemporary Nurse 2003; 14(2):138-144.

- Suokas J, Lonnqvist J. Work stress has negative effects on the attitudes of emergency personnel towards patients who attempt suicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1989; 79(5):474-480.

- Holland J, Plumb M. The management of the serious suicide attempt: a special ICU problem. Heart and Lung 1973; 2(3):376-381.

- Davidhizar R. The management of the suicide patient in a critical care unit. Journal of Nursing Management 1993; 1(2):95-102.

- Dower J, Donald M, Kelly B, Raphael B. Pathways of care for young people who present for non-fatal deliberate self-harm. Centre for Primary Health care, University of Queensland, Brisbane, 2000.

- Hopkins C. ‘But what about the really ill, poorly people? (An ethnographic study into what it means to nurses in medical admission units to have people who have harmed themselves as their patients). Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2002; 9(2):147-154.

- Sansers J. A review of health professional attitudes and patients perceptions on “inappropriate” accident and emergency attendances. The implications for current minor injury services provision in England and Wales. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2000; 31(5):1097-1105.

- Mc Laughlin C. Casualty nurses' attitudes to attempted suicide. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1994; 2 (22): 1111-1118.

- Sun F, Long A, Boore J. The attitudes of casualty nurses in Taiwan to patients who have attempted suicide. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2007; 16(2): 255-263.

- Ghodse AH. The attitudes of casualty staff and ambulance personnel towards patients who take drugs. Social Science and Medicine 1978; 12(5A):341-346.

- Anderson M. Nurses' attitudes towards suicidal behaviour- a comparative study of community mental health nurses and nurses working in an accident and emergency department. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1997; 25(6):1283-1291.

- Whitworth RA. Is your patient Suicidal? Canadian Nurse 1984; 80(6): 40-42.

- Hall D, O’Brien F, Stark C, Pelosi A, Smith H. Thirteen year follow up of deliberate self-harm, using linked date. British Journal of Psychiatry 1998; 172:239-242.

- Hawton K, Marsack P, Fagg J. The attitudes of psychiatrists to deliberate self-poisoning: comparison with physicians and nurses. British Journal of Medical Psychology 1981; 54(1):341-348.

- Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry 2002; 181:193-199.

- Beck AT, Kovacs M. Assessment of suicidal intention: The scale for suicidal intention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1979; 47(2):343-352.

- Rayner GC, Allen SL, Hohnson M. Countertransference and self-injury: a cognitive behavioral cycle. Journal of Advanced nursing 2005; 50(1):12-19.

- Morgan HG, Evans M, Johnson C, Stanton R. Can a lecture influence attitudes to suicide prevention? Journal of Research in Social Medicine 1996; 89(2):87-90.

- Samuelsson M, Asberg M. Training program in suicide prevention for psychiatric nursing personnel enhance attitudes to attempted suicide patients. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2002; 39(1):115-121.

- Crawford MJ, Turnbull G, Wessley S. Deliberate self-harm assessment by accidents and emergency staff: an intervention study. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine 1998; 15(1):18-22.

- Ouzouni Chr. and Nakakis K. Attitudes towards attempted suicide: the development of a measurement tool. Health Science Journal 2009; 3 (4):222-231.

- Eskin M. The effects of religious versus secular education on suicide ideation and suicidal attitudes in adolescent in Turkey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2004; 39(7):536-542.

- Demirkiran F, Eskin M. Therapeutic and nontherapeutic reactions in a group of nurses and doctors in Turkey to patients who have attempted suicide. Social Behavior and Personality 2006; 34 (8):891-905.

- Eskin M. Cross-Cultural tests of the gender-role consistency and stigma hypotheses of suicidal behavior. Journal of Gender, Culture and Health 1997; 2:245-262.