Keywords

Professional practice environment, nurses, physicians, job satisfaction

Introduction

Under the Lisbon strategy [1] the European Union (EU) Member States have acknowledged the major contribution that guaranteeing quality and productivity at work can play a major role in promoting economic growth and employment. Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO) [2] indicates that the work environment constitutes an important factor in the recruitment and retention of health professionals, and the characteristics of the work environment affect the quality of care both directly and indirectly. Addressing the work environment, therefore, plays a critical role in ensuring both the supply of a health workforce as well as the enhancement, effectiveness and motivation of that workforce. In the EU, improvement of the quality of work has been an integrative part of the European Social Agenda and the European Employment Guidelines since 2000. The Positive Practice Campaign [3] jointly launched by several international health-professional associations, describes characteristics of work environments that ensure the health, safety and well-being of staff, while simultaneously supporting high-quality patient care. The International Council of Nurses and other affiliated organizations suggest that, due to today’s global health workforce crisis, establishing positive practice environments across health sectors worldwide is of paramount importance if patient safety and health workers’ wellbeing are to be guaranteed. The complex social environment where nurses carry out their practice, and where there is a continuous need for health-care workers to make decisions individually, as a group and together with patients, is called the professional practice environment [2]. A nursing practice environment refers to the organizational characteristics of a work setting that facilitates or constrains professional nursing practice [2]. Furthermore, there are two similar general terms, “working environment” and “working conditions”, but there is no agreed definition of these terms. Nevertheless, the working environment generally could be described as the place, conditions and surrounding influences in which people carry out an activity. In the case of health care it refers to a set of concrete or abstract features of an organization, related to both the structures and processes in that organization that are perceived by nurses as either facilitating or constraining their professional practice [4-8]. A healthy practice environment can be defined as a work setting where policies, procedures and systems are designed in such a manner that they meet the organizational objectives and succeed in personal satisfaction at work. 7 The theoretical foundation of the professional practice environment is predicated on collaborative decision-making to ensure that all stakeholders have the opportunity to knowingly participate in change [9].

The nurses’ professional environment is receiving international interest, because there is a growing consensus that identifying opportunities for improving working conditions in hospitals is essential to maintain adequate staffing, high-quality care, nurses’ job satisfaction and hence their retention [10,11] Improving the practice environment, including patient to nurse ratios holds promise for retaining a qualified and committed nurse workforce, reducing the rates of nurse burnout and job dissatisfaction and benefiting patients in terms of better quality care [7]. Nurses’ perceptions of their professional environment influence their job satisfaction. Traditional job satisfaction relates to the feeling an individual has about his/her job. It is affected by intrinsic (recognition, work itself or responsibility) and extrinsic factors (working conditions, company policy or salary), which have an influence on job satisfaction [12]. Inadequate hospital nurse staffing contribute to uneven quality of care, medical errors, and adverse patient outcomes [13].

Job satisfaction can be defined as an employee’s affective reaction to a job, based on comparing actual outcomes with desired outcomes and is a multifaceted construct inclusive of both intrinsic and extrinsic job factors. Extrinsic factors include tangible aspects of the work like salary and benefits while intrinsic factors include personal and professional development opportunities and recognition [7]. Hospitals with poorer staffing and less adequate resources tend to appear with higher levels of nurses’ dissatisfaction and poorer quality patient care [14].

Nurses in Chinese hospitals with better work environments had lower odds of job dissatisfaction and of reporting poor or fair quality patient care and patients in such hospitals were more likely to be satisfied with nursing communications, and to recommend their hospitals [14,15].

The correlation between job satisfaction, nurse empowerment and the professional practice environment are at the foundation of the Magnet Recognition Model [16,17]. In addition, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses has conducted considerable research on the topic of Healthy Work Environment [18]. While there is already a substantial amount of literature on the professional practice environment and job satisfaction, there are only fragmented pieces of knowledge on any correlations between these issues. In more detail, what are critically missing or limited are correlational studies regarding professional practice environment as a whole and job satisfaction. Correlational studies were found regarding only specific elements of the professional practice environment (i.e. nurses-physicians relationships or nursing leadership) and job satisfaction.

To address the gap of linking PPE with job satisfaction, this review was conducted to gain an in-depth understanding and explore the correlation between the professional practice environment and nurse job satisfaction. The purpose of this paper is to describe the findings of a systematic review of studies that examined the correlation of the professional practice environment and nurse job satisfaction.

Methodology

Τhe search was performed between September and December 2012 and updated in June 2013. Relevant literature was searched across four databases to identify studies on nursing professional practice environment and nurses’ job satisfaction. The database search included: Pubmed, Google Scholar, Embase and Cinahl. The aim was to find studies published between 2000 and June 2012 (as they focus on most recent developments in this area) that examined correlations between nursing professional practice environment and job satisfaction. The key search items used included professional environment AND nurses AND physicians AND satisfaction. (We included the word physicians to increase the number of studies). Combinations of the keywords in the title and abstract were used.

Inclusion criteria

All papers were reviewed according to the following inclusion criteria:

1) correlational studies 2) measured nurses’ perceptions about professional practice environment in relation with job satisfaction 3) a sample including nurses, physicians or both 4) measured job satisfaction or dissatisfaction 5) English language articles.

Studies examining specific dimensions of the work environment (e.g. leadership, intention to leave) or other outcomes related with the professional environment (e.g. burnout, and patients’ satisfaction) were excluded, as they do not satisfy the criterion of correlating PPE and job satisfaction.

Screening

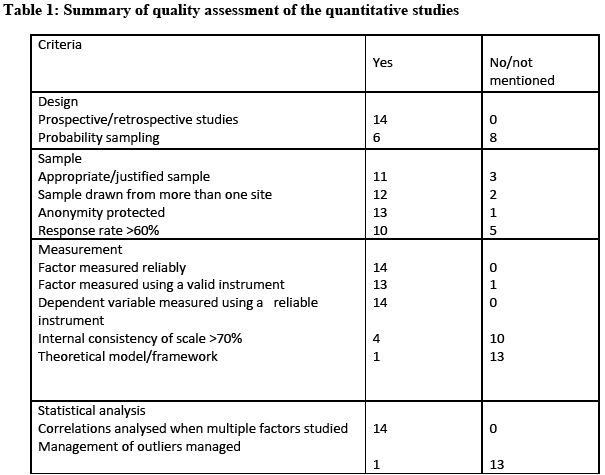

Each abstract was examined twice by two reviewers independently using the inclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if they did not examine the relationship between nursing professional practice environment as a whole and job satisfaction. The relevant studies were classified according to the degree of relevance with the scope of the study. The initial screening included the formation of a table with the following elements: author, title, objective, date of publication, instrument used, methodology and results. Then, the reviewers re-examined the studies, isolated and accepted or rejected them accordingly. For each case, a decision was taken to either exclude the paper or select it for the next step. In-depth examination of each article and data extraction were completed by the first reviewer and then validated by the second. It was still possible at this step to exclude a paper if it was deemed irrelevant or methodologically flawed according to the redefined criteria as presented in Table 1.

Data extraction

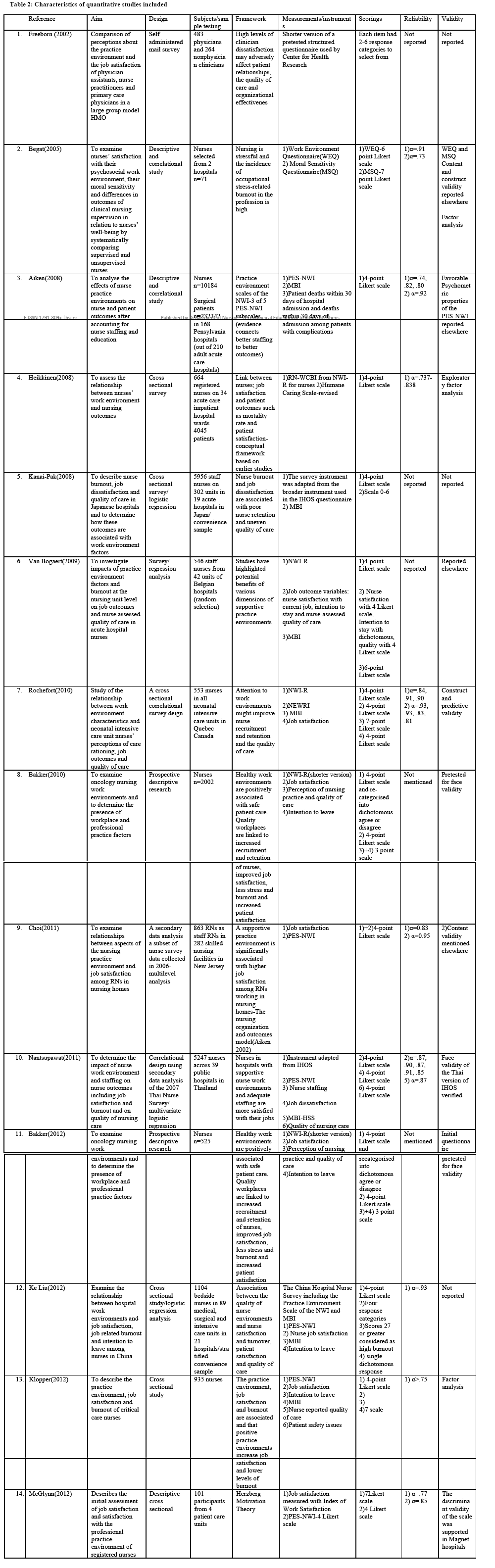

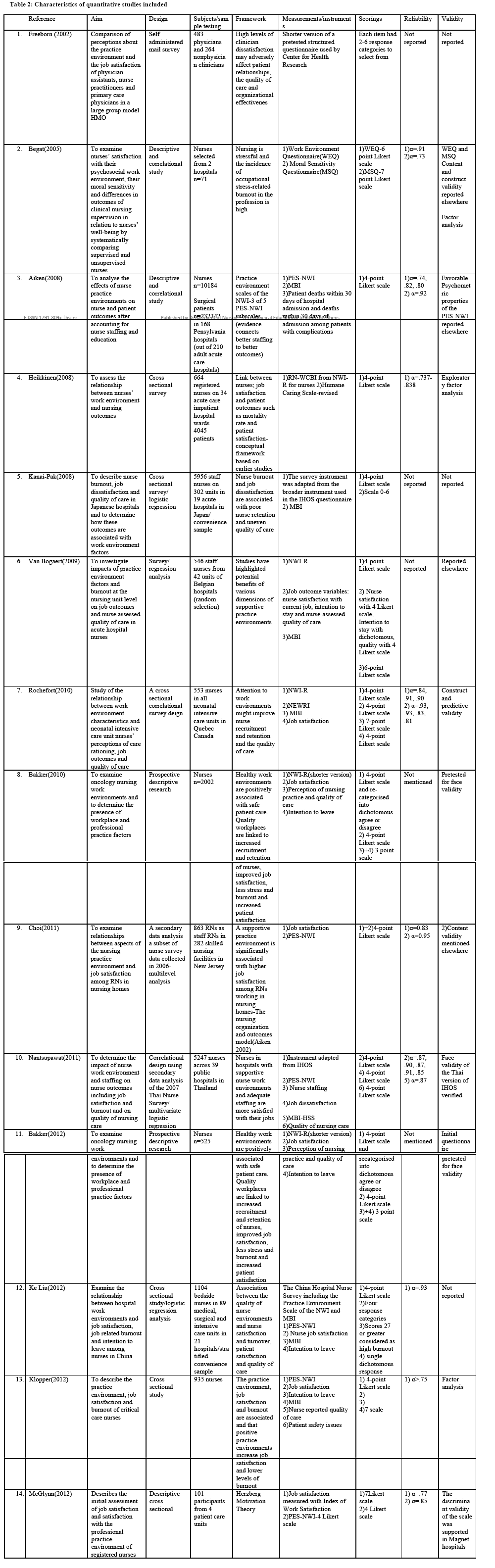

Data extracted from the studies included: author, date of publication, aim, design, subjects/sample testing, theoretical framework, measurements/instruments, scorings, reliability and validity, according to the quality assessment criteria stated in Table 1.

Quality review assessment

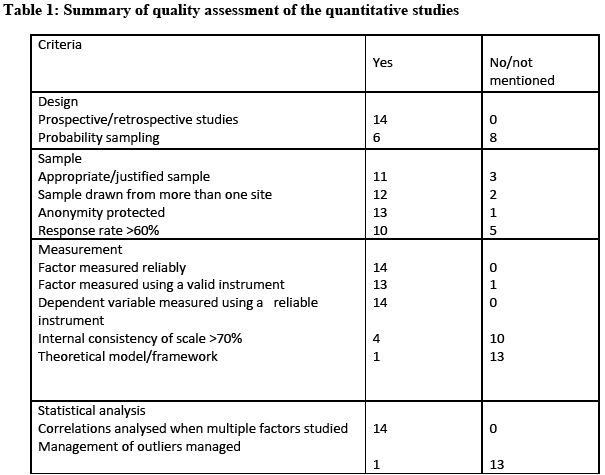

All papers selected were assessed for methodological quality prior to inclusion in the review using a standardized critical appraisal instrument [19] especially adapted for correlational studies [20,21]. This assessment tool measured overall quality based on research design, sampling method, measurement and statistical analysis. The tool comprised of 13 items, with a possible maximum score of 13 and all items were given a weight of 1 point each. An overall quality rating was assigned as low (0-4), moderate (5-9) and high quality (10-13). Only 2 studies had a score of 11 and 6 studies a score of 10, which makes in total 8 studies of high quality. This evaluation was carried out to assess all eligible studies. The rest of the studies were of moderate quality, in more detail four studies had a score of 9, one of 8 and one of 6. A summary of the quality assessment is presented in table 1.

Synthesis of results

Content analysis was used to synthesize the results from the studies. Two authors performed a preliminary synthesis to identify and summarize shared and contested constructs between and across the studies. Each author performed the synthesis separately but simultaneously, as this is considered most informative, and the resulting themes were agreed through discussion.

Results

Search results

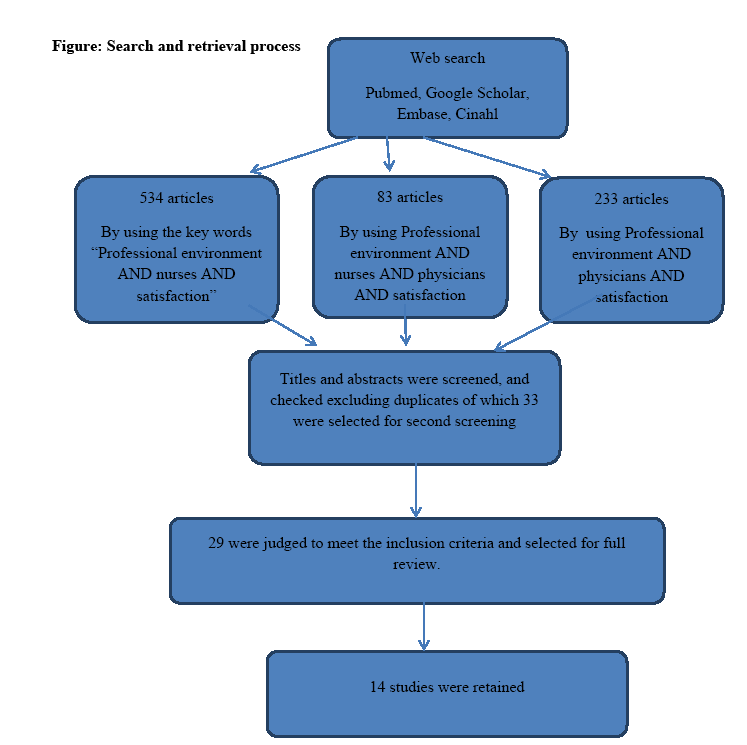

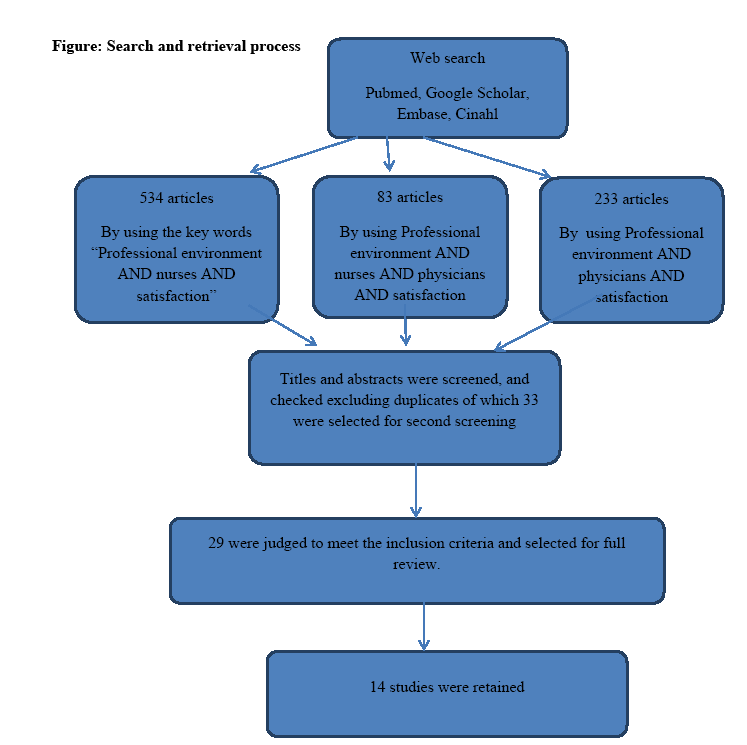

The database searches resulted in the following citations: By using the Keywords “professional environment” AND “nurses” AND “satisfaction” 534 abstracts were found across all databases; when using “professional environment” AND “nurses” AND “physicians” AND “satisfaction” 83 articles were found and 233 articles when using “professional environment” AND “physicians” AND “satisfaction”. Titles and abstracts were screened and checked excluding duplicates, of which 33 were selected for second screening. Of these 29 were judged to meet the inclusion criteria and selected for full review. These were screened in greater depth using inclusion criteria, and finally 14 studies were retained. The relevant studies were published between 2002 and 2012 (See figure for summary of search results).

Figure 1: Search and retrieval process

Quality assessment

In the quality assessment of the 14 studies, all of them were found to be of prospective/retrospective design, with 6 of them having random or convenience samples. Three of them did not justify the sample size and only two had sample drawn from more than one site. Nearly in all studies anonymity was protected. Only in 4 of the studies the response rates were below 60%.

All 14 studies used a valid and reliable instrument to measure the variables, but internal consistency was measured only in 5 of them. A big weakness of the studies was the absence of a theoretical model/framework except for one study. In all studies correlations were analyzed with multiple factors, like PPE with nursing outcomes or quality of nursing care and others. Another weakness was the omission of management of outliers, except for one study. In most of the studies (10) there is no mention of any validity evaluation. The characteristics of the studies included are presented in Table 2.

Analytical findings

Seven studies were carried out in the USA and Canada, and only two in Europe. The other five took place in China, Japan, Thailand and South Africa. Only in two studies was the sample drawn from one hospital, the rest being multi-sited. The hospitals studied were mostly public ones and the wards examined ranged from acute care units to oncology wards, nursing homes, medical and surgical wards.

The “Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index”(PES-NWI) [4] and “The Nursing Work Index-Revised” (NWI) [17] were the instruments used in most studies. Perceptions about “practice environment” and “job satisfaction” of physician assistants, nurse practitioners and primary care physicians were studied by Freeborn (2002) [22] in the USA. Bakker [23,24] targeted only oncological nurses and the research design was prospective and descriptive. Nurses were surveyed twice with a two year interval between data collection times. The study carried out in Norway by Begat in 2005 [25] measured the practice environment as well as nurses’ perceptions of moral sensitivity and well-being. The targeted professionals worked in acute medical and surgical units as well as in geriatric wards of two hospitals. In Aiken’s study [26] the sample drawn was the biggest and comprised of more than 10.000 nurses. In addition, in the same study, the hospitals studied included 168 of the 210 adult acute care hospitals. Heikkinen in 2008 [27] examined the nurses’ work environment and nursing outcomes in Finland. A cross sectional survey of 664 registered nurses in 34 acute care inpatient hospital wards was performed and patient data was collected from 4045 patients simultaneously. In 2008, Kanai-Pak [14] described nurse burnout, job dissatisfaction and quality of care in Japanese hospitals in association with work environment factors. The sample was collected from 5986 staff nurses in 302 units in 19 acute hospitals. Van Bogaert in 2009 [28] investigated impacts of practice environment factors and burnout at the nursing unit level on job outcomes and nurse assessed quality of care in 4 Belgian hospitals in 42 units with a sample 546 staff nurses.

Rochefort in 2010 [6] studied the relationship between work environment characteristics and neonatal intensive care unit nurses’ perceptions of care rationing, job outcomes and quality of care in Canada. Nantsupawat [13] refers to the impact of nurse work environment and staffing on nurse outcomes, including job satisfaction and burnout and on the quality of nursing care. The data were collected from 13 general and 26 regional hospitals in Thailand, with a sample of 5247 nurses. KeLiu [29] examined the relationship between hospital work environments and job satisfaction, job-related burnout and intention to leave among 1104 nurses from 89 medical, surgical and intensive care units in 21 hospitals in China. Klopper in 2012 [7] included in the study private hospitals as well as national referral hospitals in South Africa in a sample of 935 nurses. The objective of this study was to describe the practice environment, job satisfaction and burnout of critical-care nurses in South Africa and the relationship between them. McGlynn (2012) [8] studied in the USA ‘job satisfaction’ and ‘satisfaction with the professional practice environment’ of registered nurses in places where a professional practice model was implemented as well as the relationship between these two variables. The sample was drawn from only one hospital, from different types of wards, with a response rate of 55%.

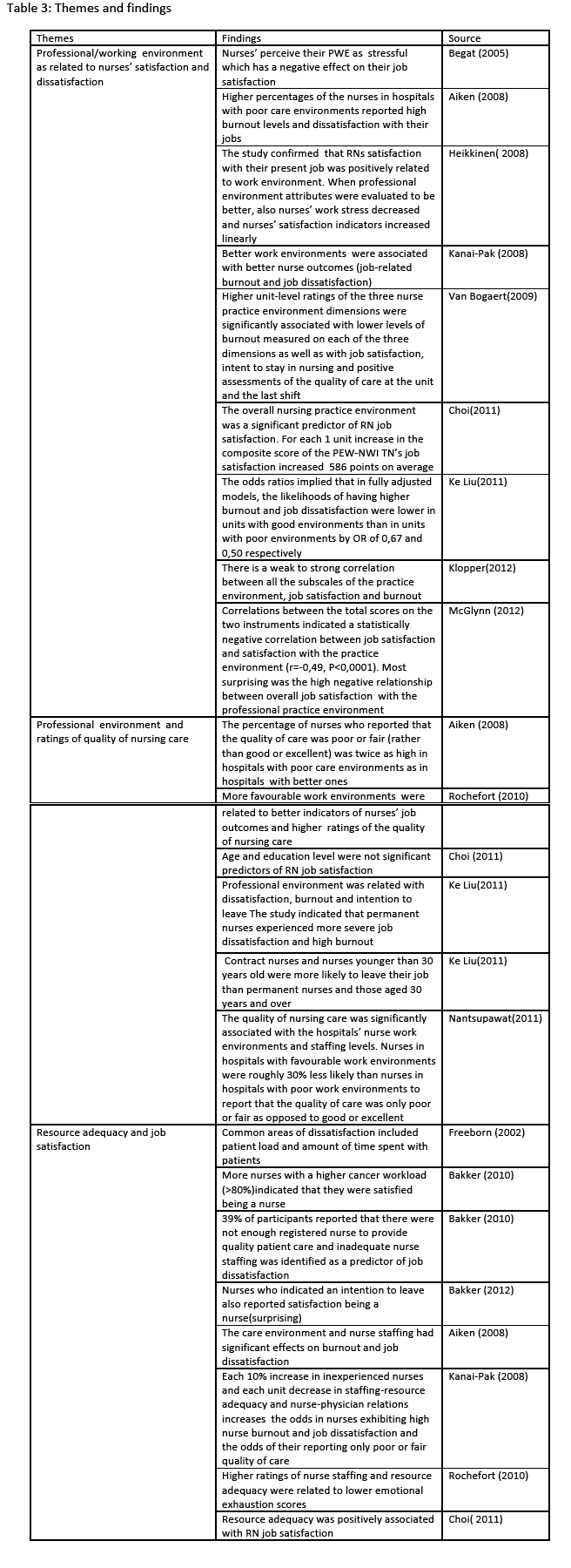

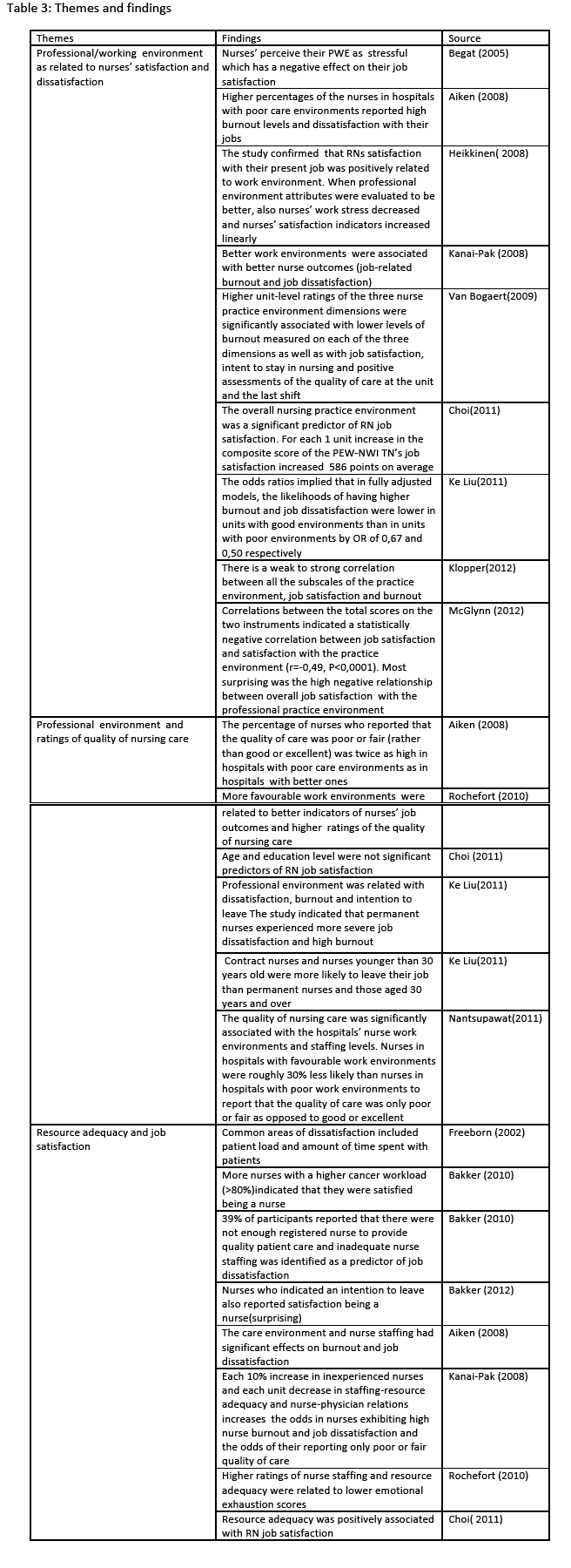

Three main correlations were defined as “themes” to facilitate the analysis. In particular, these are: “Professional/working environment as related to nurses’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction”, “Professional environment and ratings of quality of nursing care” and “resource adequacy and job satisfaction”. See Table 3.

a) Professional/working environment as related to nurses’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction

Nurses perceived their Professional Working Environment as stressful, which had a negative effect on their job satisfaction [25]. In 5 studies, higher percentages of the nurses in hospitals with poor care environments reported dissatisfaction and high burnout levels with their jobs [7,27-30]. In more detail, registered nurses’ (RN) satisfaction with their present job was positively related to work environment [27] and likelihoods of having higher burnout and job dissatisfaction were lower in units with good environments than in units with poor environments [29]. Better work environments were associated with better nurse outcomes in contrast to job-related burnout and job dissatisfaction [14]. The overall nursing practice environment was a significant predictor of RN job satisfaction [30].

Nevertheless, in one study most surprising was the high negative relationship between overall job satisfaction with the professional practice environment. Correlations between the total scores on the two instruments used by McGlynn, [8] indicated a statistically negative correlation between job satisfaction and satisfaction with the practice environment. In more detail, where a professional practice model is in place, that is a strategy that aids hospitals in maintaining their nursing workforce and increasing the quality of nurses’ work life through its positive effect on nurses’ job satisfaction, nurses reported moderately low overall work satisfaction. This result may be due to the fact that the study was carried out in only one hospital and only 55% of the eligible nurses participated.

b) Professional environment and ratings of quality of nursing care

The percentage of nurses reporting that the quality of care was poor or fair (rather than good or excellent) was twice as high in hospitals with poor care environments as in hospitals with better ones [26] and more favourable work environments were related to better indicators of nurses’ job outcomes and higher ratings of the quality of nursing care [6]. The quality of nursing care was significantly associated with the hospitals’ nurse work environments and staffing levels. Nurses in hospitals with favourable work environments were roughly 30% less likely than nurses in hospitals with poor work environments to report that the quality of care was only poor or fair as opposed to good or excellent [13]. In one study contract nurses and nurses younger than 30 years old were more likely to leave their job than permanent nurses and those aged 30 years and over, [29] whereas other age and education levels were not significant predictors of RN job satisfaction [30].

c) Resource adequacy and job satisfaction

The care environment and nurse staffing were found to have significant effects on burnout and job dissatisfaction. Nurse retention and patient outcomes are improved when the nurse leaders improve staffing [31]. Higher ratings of nurse staffing and resource adequacy were related to lower emotional exhaustion scores [6]. Each 10% increase in inexperienced nurses and each unit decrease in staffing-resource adequacy and nurse-physician relations increases the odds in nurses exhibiting high nurse burnout and job dissatisfaction and the odds of their reporting only poor or fair quality of care [14]. 39% of participants reported that there were not enough registered nurses to provide quality patient care and inadequate nurse staffing was identified as a predictor of job dissatisfaction [23]. Resource adequacy was positively associated with RN job satisfaction [22,30].

Discussion

The results of this review provided evidence that nurses’ perceptions of their professional practice environment and resource adequacy, are related to nurse satisfaction and patient outcomes such as nurse perceived quality of care. Establishing positive practice environments across health sectors worldwide is of paramount importance if patient safety and health workers’ wellbeing are to be guaranteed. Positive Practice Environments are settings that support excellence and decent work [2]. In particular, they strive to ensure the health, safety and personal wellbeing of staff, support quality patient care and improve the motivation, productivity and performance of individuals and organizations. Positive changes in the work environment result in a higher employee retention rate, which leads to better teamwork, increased continuity of patient care, and ultimately improvements in patient outcomes.

Health care is changing. Ageing populations, new therapeutic possibilities and rising expectations have made the provision of health care much more complex than in the past. At the heart of these changes are the health professionals [32].

The overall goal of every healthcare organization is to systematically develop and reinforce organizational strategies, structures and processes that improve the organization’s effectiveness in achieving quality patient care and employee job satisfaction. Thus, healthy work environments are linked to patients’ satisfaction and to retention, reduced turnover, increased attraction, job satisfaction and lower degree of job stress and burnout.

Transitions in health care have globally sparked public and professional concern regarding the professional practice environment for nurses and its effect on the quality of care. Nurses make up the largest cohort of health providers. A professional practice environment is needed to enhance and optimize nurses’ potentials to deliver quality patient care. Research supports the belief that the nurses’ professional practice environment significantly relates to nurse and patient outcomes. The professional practice environment has been implicated as a variable that impacts patient outcomes [33]. The professional practice environment for nurses is an important topic of study across many health care systems. An environment without support for nurses performing professional practice hinders the delivery of good health care for patients. From the studies retrieved, it is evident that in comparison to the available published literature on professional practice environment and job satisfaction separately, little research has focused exclusively on the correlation between the two variables. Intention to leave and burnout as well as building elements of the professional environment like nurses’ physicians relationships, quality of care, patients’ outcome are prominent in many studies. On the other hand, the study of the correlation between professional practice environment as a whole and job satisfaction is limited. It is prominent in many of the selected studies that increasing percentages of the nurses in hospitals with poor environments report high burnout levels and dissatisfaction with their jobs. Nurses reported more positive job experiences and fewer concerns with care quality and patients had significantly lower risks of death and failure to rescue in hospitals with better care environments [26]. If nurses perceive their working environment as stressful, that has a negative impact on job satisfaction [25]. Many research reports support that the key to the nursing shortage is attention to nursing work environments. An important aspect of the practice environment associated with job satisfaction includes leadership and support for nurses. Nursing managers can contribute to nurses’ satisfaction by ensuring among others that staff receive recognition for a job well done [30]. Management and leadership are important for the delivery of good health services. These two terms are not the same thing but they are necessarily linked and complementary. The manager’s job is to plan, organize and coordinate. An effective nursing manager who consults with staff and provides positive feedback is crucial in increasing job satisfaction [34]. As it is well known that nurses’ work environment is a major determinant of patient and nurse welfare, we can fairly claim that nurses’ professional environment is of positive influence on nursing outcomes [27]. Furthermore, the subscales “nurse manager ability, leadership and support” and “nurse participation in hospital affairs” had the strongest correlations with the “job satisfaction” in the studies reviewed, thus confirming that these elements play a critical role in the development of a positive practice environment [7]. Improving nurses’ work environment from poor to better was associated with a 50% decrease in job dissatisfaction and a 33% decrease in burnout among nurses [29]. Positive ratings of nurse practice environment factors are also associated with improved job outcomes and higher nurse ratings of quality of care [28].

Limitations

The intention of this review was to examine the available research studies that explored the correlation of professional practice environment and nurse job satisfaction. Details of the participants in the studies included were not fully described and were complicated by the various titles used due to the fact that the studies had been carried out in different countries with different health systems. In some studies the participants were nurses as well as other health professionals, thus making the summarization of the results not so homogeneous. A major limitation can be the inclusion of only quantitative studies in this review. Thus, there is a need for examining the issue of the relation of the professional practice environment with job satisfaction through further exploration of studies that use different methodological approaches.

Conclusions

Evidence suggests that the work environment is an important factor in the recruitment and retention of health workers. Furthermore, the work environment can influence the quality of care and patient safety. As a working definition, an attractive and supportive workplace in this case can be described as an environment that attracts individuals into the health professions, encourages them to remain in the health workforce and enables them to perform effectively.

In most studies it was evident that there is a positive relationship between nursing professional practice environment and job satisfaction. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to determine and measure the degree of such correlations. The knowledge gained from future studies that result in the development of theoretical concepts and theories will add to the knowledge available in the area of nursing management. Professional Practice Environments demonstrate a commitment to safety in the workplace, leading to overall job satisfaction. When health professionals are satisfied with their jobs, rates of absenteeism and turnover decrease, staff morale and productivity increase, and work performance as a whole improves. Safe patient care is directly and positively linked to the quality of nurses’ work environments.

The insights gained from the synthesis of the studies reviewed allow us to have a better understanding of the impact of the professional practice environment on job satisfaction and what implications this relation might have on various aspects of the provision of health care. Further work is needed to investigate this relationship so that theoretical concepts could be developed and knowledge will be added in the area of an efficient and effective professional practice environment that will contribute to the upgrade of the quality of the health services provided.

This review will provide health policy-makers and managers with an effective tool to promote a sound professional practice environment so that job satisfaction is secured and ultimately health organizations can achieve the goal of providing quality care for health consumers. These findings suggest that investing in a good professional practice environment is reflected in nurses’ well-being and job satisfaction, thus improving the outcomes for patients.

2666

References

- Commission of the European Communities. Improving quality and productivity at work: Community strategy 2007-2012 on health and safety at work [Internet]. Brussels 21.2.2007; 2007. Report No.: COM(2007) 62 final. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/;jsessionid=vpT8TvyTxMXKyyVZBm0TzL5ZwD6rYLl0hc9L6jJJGYnpsnQPpxknm!428133741?uri=CELEX:52007DC0062

- Wiskow C, Albreht T, Pietro C De. How to create an attractive and supportive working environment for health professionals. Copenhagen; 2010. Report No.: Policy Brief 15.

- International Council of Nurses, International Hospital Federation, International Pharmaceutical Federation, World Confederation for Physical Therapy, World Dental Federation WMA. Positive practice environments for health care professionals [Internet]. 2008. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/images/stories/documents/publications/fact_sheets/17d_FS-Positive_Practice_Environments_HC_Professionals.pdf

- Lake ET. Development of the practice environment scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res Nurs Health 2002;25(3):176–88.

- Hoffart N, Woods CQ. Elements of a nursing professional practice model. J Prof Nurs 1996;12(6):354–64.

- Rochefort CM, Clarke SP. Nurses’ work environments, care rationing, job outcomes, and quality of care on neonatal units. J Adv Nurs 2010;66(10):2213–24.

- Klopper HC, Coetzee SK, Pretorius R, Bester P. Practice environment, job satisfaction and burnout of critical care nurses in South Africa. J Nurs Manag 2012;20(5):685–95.

- McGlynn K, Griffin MQ, Donahue M, Fitzpatrick JJ. Registered nurse job satisfaction and satisfaction with the professional practice model. J Nurs Manag 2012;20(2):260–5.

- Erickson JI, Duffy ME, Ditomassi M, Jones D. Psychometric evaluation of the Revised Professional Practice Environment (RPPE) scale. J Nurs Adm 2009;39(5):236–43.

- Hinno S, Partanen P, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Aaviksoo A. Nurses’ perceptions of the organizational attributes of their practice environment in acute care hospitals. J Nurs Manag 2009;17(8):965–74.

- Rafferty A M, Ball J, Aiken LH. Are teamwork and professional autonomy compatible, and do they result in improved hospital care? Qual Health Care 2001;10 Suppl 2(Suppl II):ii32–7.

- Szecsenyi J, Goetz K, Campbell S, Broge B, Reuschenbach B, Wensing M. Is the job satisfaction of primary care team members associated with patient satisfaction? BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20(6):508–14.

- Nantsupawat A, Srisuphan W, Kunaviktikul W, Wichaikhum O-A, Aungsuroch Y, Aiken LH. Impact of nurse work environment and staffing on hospital nurse and quality of care in Thailand. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011;43(4):426–32.

- Kanai-Pak M, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Poghosyan L. Poor work environments and nurse inexperience are associated with burnout, job dissatisfaction and quality deficits in Japanese hospitals. J Clin Nurs 2008;17(24):3324–9.

- You L, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Liu K, He G, Hu Y.Hospital nursing, care quality, and patient satisfaction: cross-sectional surveys of nurses and patients in hospitals in China and Europe. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50(2), 154-161.

- Aiken LH, Buchan J, Ball J, Rafferty AM. Transformative impact of Magnet designation: England case study. J Clin Nurs 2008;17(24):3330–7.

- Aiken L, Patrician P. Measuring organizational traits of hospitals: the Revised Nursing Work Index. Nurs Res 2000; 49(3), 146-153.

- Erickson J, Jones D, Ditomassi M. Fostering Nurse-led Care: Professional Practice for the Bedside Leader from Massachusetts General Hospital Sigma Theta Tau 2012 Chapter 2

- Cummings GG, MacGregor T, Davey M, Lee H, Wong C a, Lo E, et al. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47(3):363–85.

- Thorpe C, Ryan B, McLean SL, Burt a, Stewart M, Brown JB, et al. How to obtain excellent response rates when surveying physicians. Fam Pract 2009;26(1):65–8.

- Papastavrou E, Andreou P, Tsangari H, Schubert M, De Geest S. Rationing of Nursing Care Within Professional Environmental Constraints: A Correlational Study. Clin Nurs Res 2014;23(3):314-35.

- Freeborn DK, Hooker RS, Pope CR. Satisfaction and Well-Being of Primary Care Providers in Managed Care. Eval Health Prof 2002;25(2):239–54.

- Bakker D, Conlon M, Fitch M, Green E. Canadian oncology nurse work environments: part I. Nursing Leadership 2010;22(4):50-68.

- Bakker D, Conlon M, Fitch M, Green E, Butler L, Olson K, et al. Canadian Oncology Nurse Work Environments: Part II. Nursing Leadership 2012;25(1):68-89.

- Bégat I, Ellefsen B, Severinsson E. Nurses’ satisfaction with their work environment and the outcomes of clinical nursing supervision on nurses' experiences of well-being - a Norwegian study. J Nurs Manag 2005;13(3):221–30.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm 2008;38(5):223–9.

- Tervo-Heikkinen T, Partanen P, Aalto P, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. Nurses’ work environment and nursing outcomes: a survey study among Finnish university hospital registered nurses. Int J Nurs Pract 2008;14(5):357–65.

- Van Bogaert P, Clarke S, Roelant E, Meulemans H, Van de Heyning P. Impacts of unit-level nurse practice environment and burnout on nurse-reported outcomes: a multilevel modelling approach. J Clin Nurs 2010;19(11-12):1664–74.

- Liu K, You L-M, Chen S-X, Hao Y-T, Zhu X-W, Zhang L-F, et al. The relationship between hospital work environment and nurse outcomes in Guangdong, China: a nurse questionnaire survey. J Clin Nurs 2012;21(9-10):1476–85.

- Choi SP-P, Pang SM-C, Cheung K, Wong TK-S. Stabilizing and destabilizing forces in the nursing work environment: a qualitative study on turnover intention. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48(10):1290–301.

- Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm 2008; 38(5):223–9

- Rechel B, Dubois C, McKee M. The health care workforce in Europe: learning from experience. 2006

- Siedlecki S, Hixson E. Development and Psychometric Exploration of the Professional Practice Environment Assessment Scale. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011;43(4), 421-425.

- Roche M, Duffield C, White E. Factors in the practice environment of nurses working in inpatient mental health: A partial least squares path modeling approach. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48(12):1475–86.