Keywords

gastrointestinal tract cancers; Suriname; incidence; distribution; gender; age; ethnic background.

Introduction

Cancers of the gastrointestinal tract are malignancies arising from the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon and rectum, anus and anal canal, liver, pancreas, and/or gallbladder. These neoplasms are collectively among the most prevalent, but also the most deadly conditions known to mankind, accounting worldwide for more than 30% of new cancer cases and almost 40% of cancer fatalities [1]. Among the most common subtypes are colorectal, gastric, and primary hepatic cancer, which are each year newly diagnosed in more than two million men and about 1.25 million women [1]. Regrettably, almost three-quarters of these patients eventually die from their disease [1]. These devastating results are for an important part attributable to the fact that gastrointestinal tumors are often detected at an advanced stage, when they are not curable by resection and respond poorly to chemotherapy [2-5].

Incidence rates of gastrointestinal tract cancers vary widely throughout the world. These differences have largely been related to regional variations in the distribution of associated risk factors. For instance, colorectal cancer is most frequently seen in industrialized areas [1], where it has been linked to physical inactivity, overweight, and obesity [6,7]; the consumption of red and processed meat [8,9]; excessive alcohol consumption [10]; and cigarette smoking [11,12]. However, its prevalence is rising in economically developing countries with an aging population and an increasingly westernized lifestyle (such as Brazil) [13]. Cancer of the stomach occurs at relatively high rates in Eastern Asia [1], where it has been related to the consumption of excessively salted or otherwise preserved foods but insufficient amounts of fresh fruits and vegetables [14,15]; chronic Helicobacter pylori infection [16,17]; and cigarette smoking [17]. Primary liver cancer incidence is particularly high in parts of Asia and Africa that are struck by chronic hepatitis B and C virus infection [16], with or without aflatoxin B1 exposure [18]. In low-risk Western countries, most cases are attributable to alcohol-related cirrhosis and possibly non-alcohol fatty liver disease associated with obesitas [19].

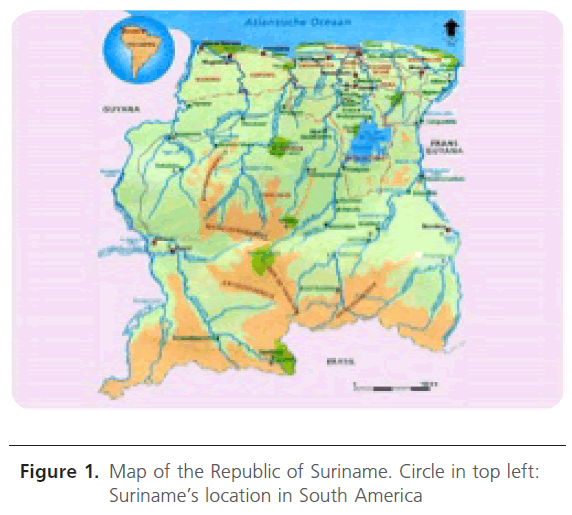

The Republic of Suriname is situated on the north-east coast of South America, and borders north to the Atlantic Ocean, south to Brazil, east to French Guyana, and west to Guyana (Figure 1). The country’s main economic activities are gold and bauxite mining, crude oil drilling, agriculture, fishery, forestry, ecotourism, commerce, services, and industry [20]. The gross national income per capita is around U$ 7,000 [20], which positions Suriname among the upper middle income countries on the World Bank’s list of economies [21]. At the same time, more and more Surinamese are adapting a Western life-style. Recently, the Pan American Health Organization reported that almost one-third of Surinamese adolescents do not consume sufficient fruits and vegetables, that nearly half has too little physical activity, and that about 10% is an active cigarette smoker [22,23]. Not surprisingly, about one out of five of this group is overweight, and approximately one out of fifteen is obese [22,23]. As far as Surinamese adults are concerned, roughly half is overweight, about one-quarter is obese, more than one-quarter smokes, and approximately one-third consumes alcohol at higher than average amounts [22,23].

Figure 1. Map of the Republic of Suriname. Circle in top left: Suriname’s location in South America

These observations suggest that Suriname, similarly too many other economically developing countries, is facing increasing threats of lifestyle-related non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular ailments, diabetes mellitus, and certain types of cancer [24-26]. Notably, these conditions represent the three most important causes of mortality in the country, accounting each year for over 40% of deaths [27]. So far, however, no comprehensive studies have been performed on the potential magnitude of this problem for public health in Suriname. This also holds true for a typically lifestyle-related group of cancers such as those of the gastrointestinal tract. For this reason, we determined incidence rates of these malignancies in the country for the period between the years 1980 and 2008, overall as well as for the various anatomical sites. The data obtained have been stratified according to gender, age at the time of diagnosis, and ethnic background, and have been discussed within the framework of international incidence patterns.

Patients and methods

Study population

In this study, the histopathologically confirmed malignant gastrointestinal cancers registered in Suriname between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2008, have been inventoried and stratified on the basis of histology, as well as gender, age at the time of diagnosis, and ethnic origin. Benign lesions, in situ carcinomas, and gastrointestinal lymphomas have been excluded from the study.

Sources of data

Relevant patient data were obtained from the Pathologic Anatomy Laboratory of the Academic Hospital of Paramaribo, the referral center for histopathological cancer diagnosis and cancer registration in Suriname. Cancer cases are classified using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology [28]. Patients’ records include, among others, histopathological diagnosis, gender, date of birth, as well as ethnic origin, and have been treated confidentially.

Population data, including estimates of the mid-year population of Suriname for each year covered by this study, were provided by the Section Population Statistics of the General Bureau of Statistics from the Ministry of Planning and Developmental Cooperation [29,30]. Estimates of the male and female resident populations were derived from the total mid-year populations on the basis of reports indicating that both genders were more or less equally distributed over the Surinamese population [29,30].

Data analysis

For each year between 1980 and 2008, numbers of overall gastrointestinal cancers, as well as numbers of cancers from the individual anatomical sites have been determined for males and females; for cases aged between 0 and 19 years, between 20 and 49 years, and above 50 years; and for the four largest ethnic groups, viz. Hindustanis (the descendents from contract workers attracted from Eastern India), Creoles (those from mixed black and white ancestry), and Javanese (the descendents from contract workers from the Indonesian island of Java). These groups comprise approximately 27, 18, and 15%, respectively, of the total Surinamese population [30]. Notably, even though these sub-populations have settled for at least a century in Suriname, their composition is still fairly homogeneous, because interracial marriages are even now rather uncommon. Average yearly crude incidence rates were estimated by dividing the number of cancer cases for each group by the estimated mid-year resident total population, and were expressed per 100,000 populations.

Statistics

Data presented are means ± SDs and have been compared using Student’s t test or ANOVA, taking P values < 0.05 to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Overall data

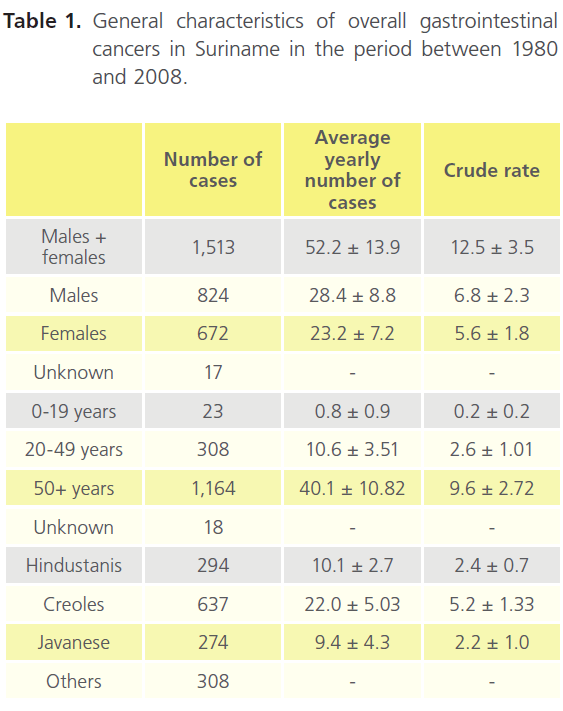

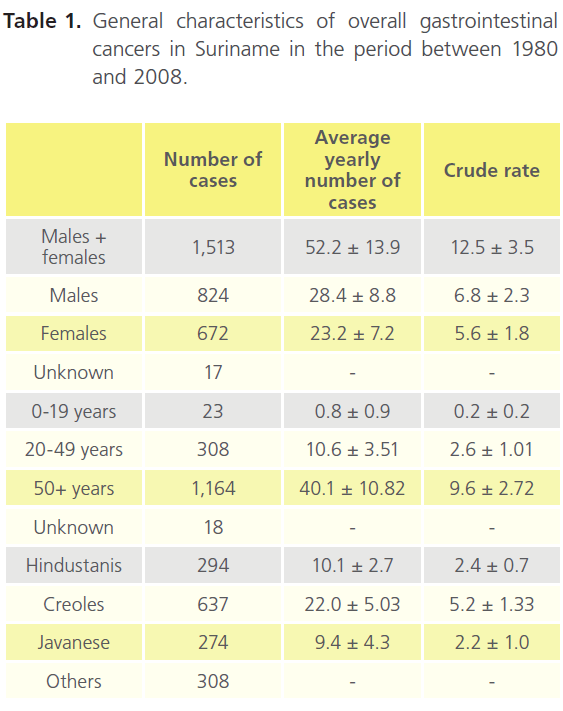

Between the years 1980 and 2008, a total of 1,513 individuals were newly diagnosed with a malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract (Table 1). This was consistent with approximately 52 new patients per year or one new patient per week, and an overall incidence rate of about 12 cases per 100,000 populations per year (Table 1). The male-to-female-ratio was approximately 55 : 45 (Table 1), indicating that gastrointestinal tract malignancies occurred almost as often in men as in women (at average rates of roughly 25 men or women per year, or 6 men or women per 100,000 population per year; Table 1).

The age distribution of overall gastrointestinal cancers showed a marked increase with increasing age. In the 29 years covered by this study, there were only 23 cases in individuals of 19 years and younger, but more than 300 cases in the age group between 20 and 49 years, and almost four times more in patients of 50 years and older (Table 1). This corresponded to only 1 case per year in the youngest age group, about 10 cases per year in age group 20 to 49 years, and about 40 cases per year in the group of 50 years and older (Table 1). Thus, gastrointestinal tract malignancies manifested predominantly in older individuals.

Table 1. General characteristics of overall gastrointestinal cancers in Suriname in the period between 1980 and 2008.

Almost 80% of overall gastrointestinal cancers (1,205 out of 1,513) was diagnosed in representatives of the three largest ethnic groups, i.e., Hindustanis, Creoles, and Javanese (Table 1). Approximately one-quarter of this group was Hindustani, about one-quarter was Javanese, but almost half was Creole (Table 1), and incidence rates were about 2, 2, and 5, respectively, per 100,000 population per year (Table 1). Accordingly, cancers of the gastrointestinal tract seemed to be twice more common in Creoles than in Hindustanis and Javanese.

Incidence of gastrointestinal tract malignancies by gender

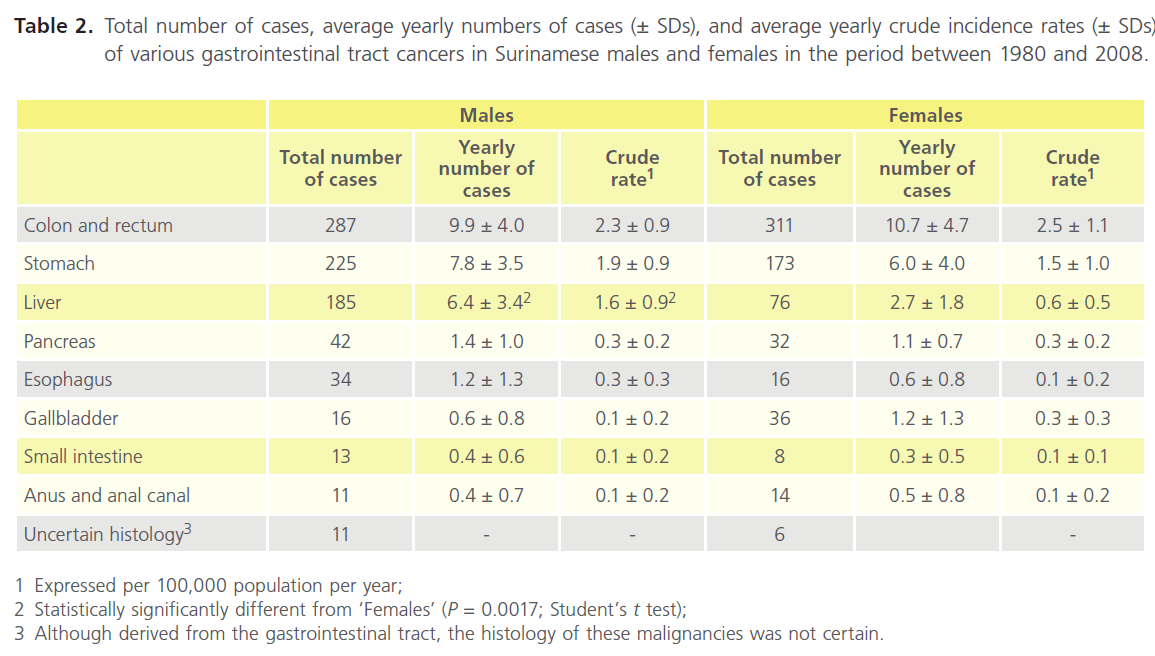

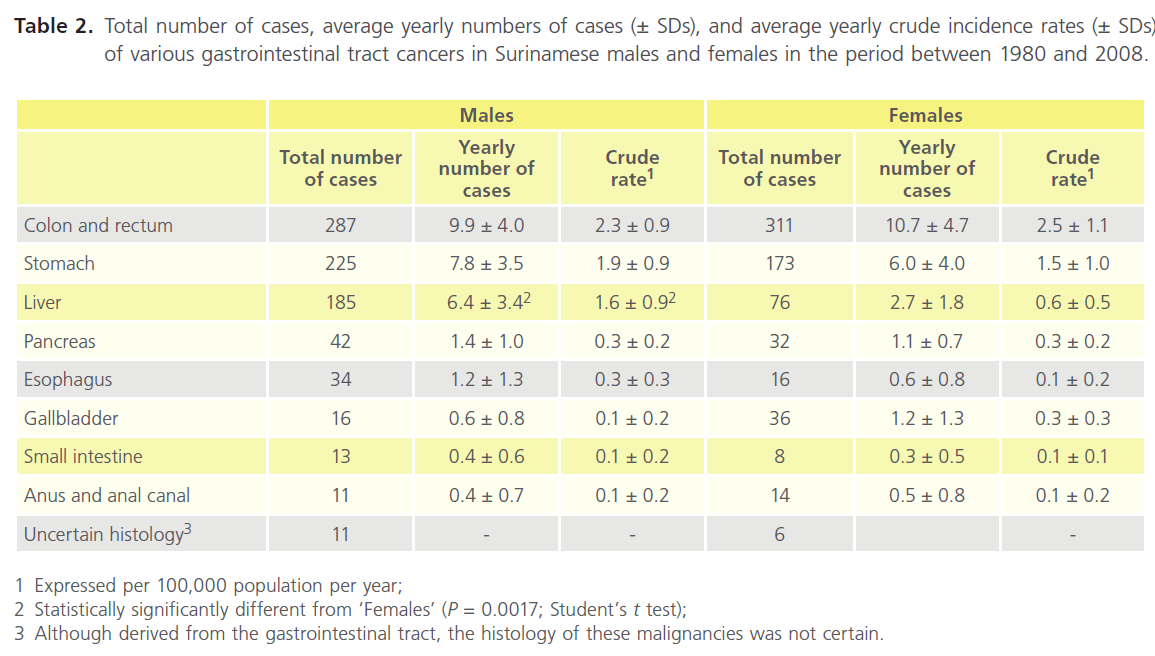

The most common cancers of the digestive system between 1980 and 2004 in both males and females were colorectal, stomach, and liver cancer (Table 2). These malignancies accounted in each gender for approximately 85% of the total number of gastrointestinal tract malignancies diagnosed in this period.

Table 2. Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (± SDs), and average yearly crude incidence rates (± SDs) of various gastrointestinal tract cancers in Surinamese males and females in the period between 1980 and 2008.

Cancers of the colon and rectum comprised in males more than one-third and in females almost half of the total number of gastrointestinal cancers (Table 2). This corresponded to incidence rates of roughly 2 and 3 cases, respectively, per 100,000 populations per year in each gender (Table 2). Cancer of the stomach was seen in approximately one-quarter of both men and women (Table 2) and at rates of about 2 per 100,000 per year in both genders (Table 2). On the other hand, primary hepatic cancer was seen in 23% of males and 11% of female patients (Table 2), and at rates of about 1.6 and 0.6 case(s), respectively, per 100,000 populations per year (Table 2). Apparently, colorectal and gastric neoplasms were as common in men as in women, but primary liver cancer seemed to occur about twice more often in men than in women.

Cancers of the pancreas, esophagus, gallbladder, small intestine, as well as anus and anal canal comprised together 14 and 18% of gastrointestinal tract malignancies in males and females, respectively. They occurred in both genders at rates of at the most 1 per 100,000 men or women per year (Table 2).

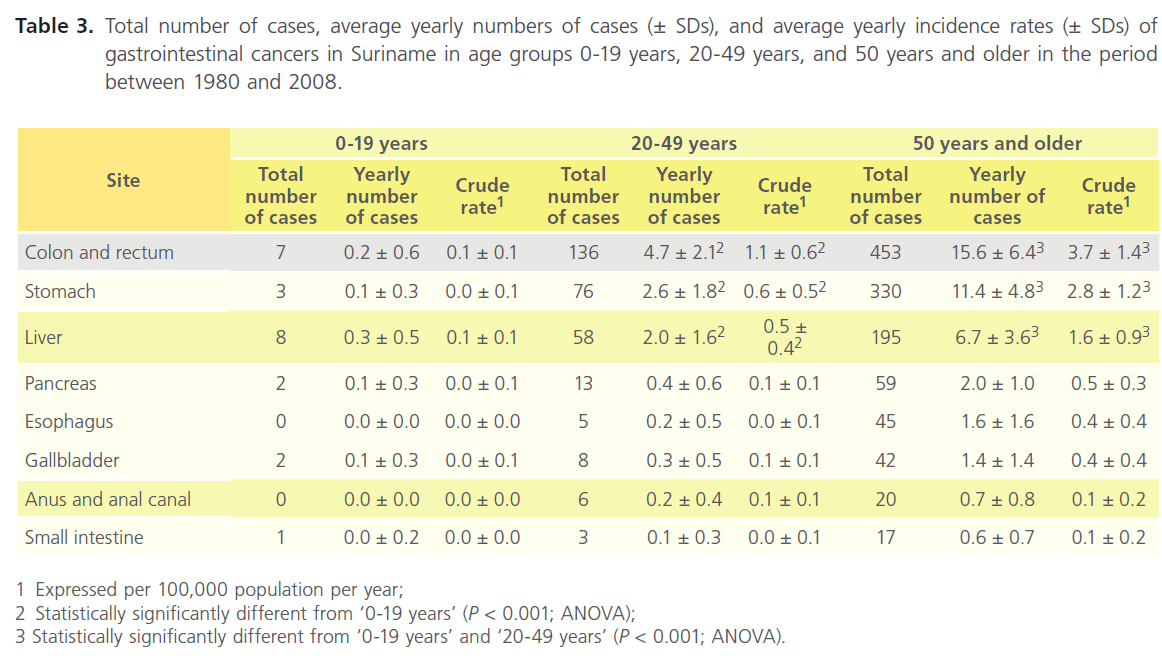

Incidence of gastrointestinal tract malignancies by age group

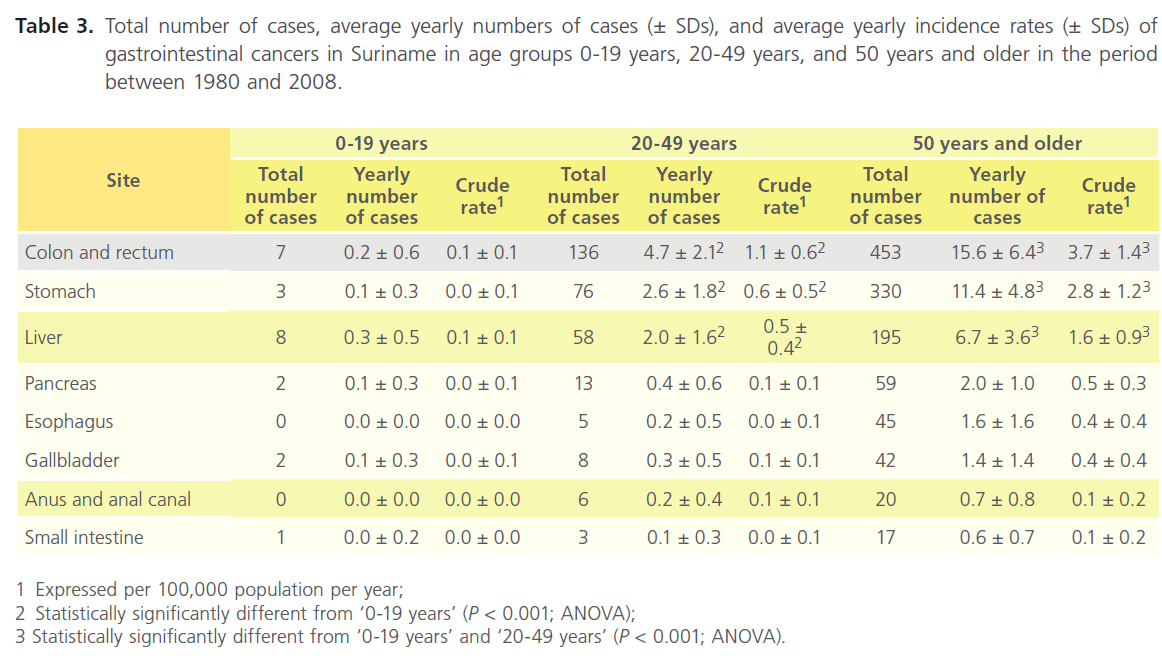

As observed for gastrointestinal cancers overall (Table 1), the incidence rates for the individual gastrointestinal tract cancers increased with increasing age (Table 3). For all histiotypes, the number of patients between 0 and 19 years of age comprised less than 4 % of the total number of cases, that between 20 and 49 years 10 to 23 %, and that of 50 years and older more than 74 % (Table 3). This trend was particularly evident for colorectal, stomach, and liver cancer: there were only a few cases in the youngest age group, but 2 to 5 cases per year in the group of 20 to 49 years, and 7 to 16 cases per year in that of 50 years and older (Table 3).

Table 3. Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (± SDs), and average yearly incidence rates (± SDs) of gastrointestinal cancers in Suriname in age groups 0-19 years, 20-49 years, and 50 years and older in the period between 1980 and 2008.

Cancers of the pancreas, esophagus, gallbladder, anus and anal canal, as well as small intestine were virtually non-existent in individuals aged 0 to 19 years, occurred at slightly higher numbers in those of 20 to 49 years, and at frequencies up to 2 per year in those of 50 years and older (Table 3).

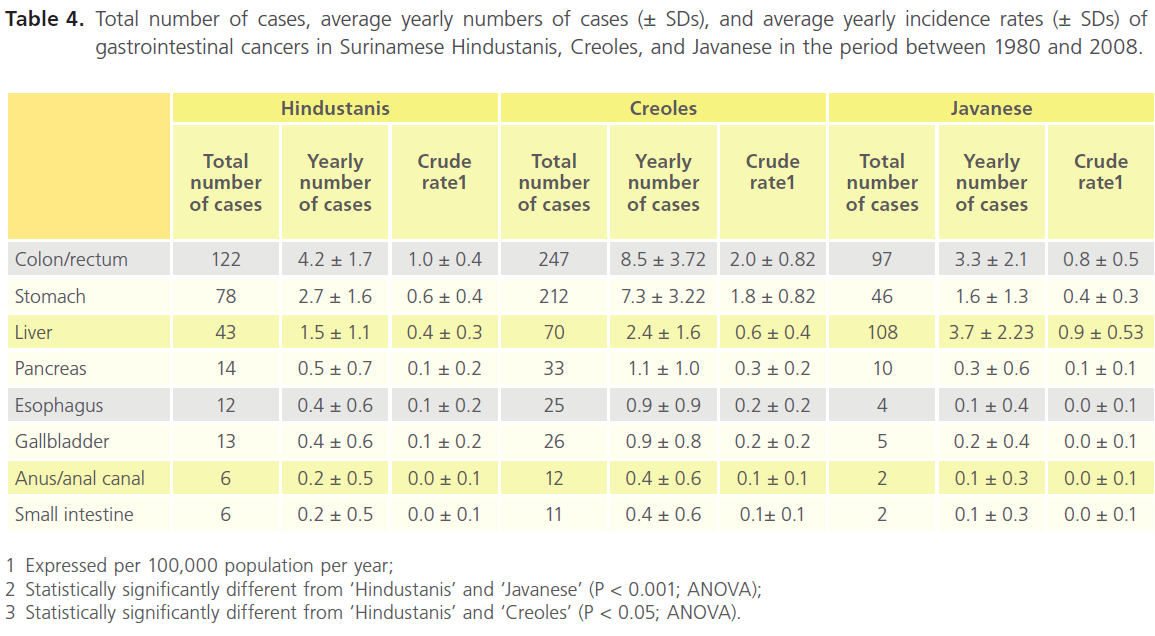

Incidence of gastrointestinal tract malignancies by ethnic background

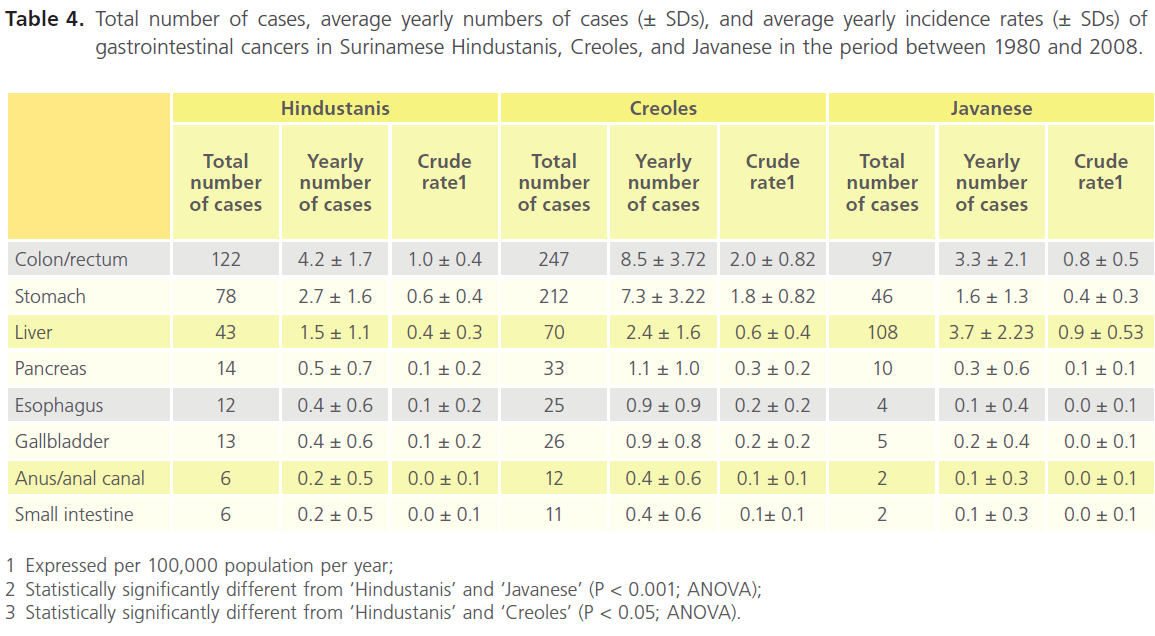

Similarly to overall gastrointestinal malignancies (Table 1), most malignancies from the various sub-sites were also more frequently seen in Creoles than in Hindustanis and Javanese (Table 4). Notably, approximately 41% of colorectal cancers and more than 50% of stomach cancers were diagnosed in Creoles (Table 4), which was at least twice more when com pared to Hindustanis and Javanese (Table 4). The incidence rates of these malignancies were 2, 0.6 - 1.0, and 0.4 - 0.8 per 100,000 population per year in Creoles, Hindustanis, and Javanese, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (± SDs), and average yearly incidence rates (± SDs) of gastrointestinal cancers in Surinamese Hindustanis, Creoles, and Javanese in the period between 1980 and 2008.

A comparable pattern was observed for cancers of the pancreas, esophagus, gallbladder, anus and anal canal, and small intestine. During the period covered by this study, there were up to 24 cases in Creoles, but no more than 11 and 9 in Hindustanis and Javanese, respectively (Table 4).

The exception to this trend was primary liver cancer: about 16 and 27% of cases was Hindustani or Creole, respectively, but more than 40% was Javanese (Table 4). The incidence rate in the latter group was approximately 2 per 100,000 populations per year (Table 4).

Discussion

This paper reports on the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers in the Republic of Suriname between the years 1980 and 2008, and compares the findings to international data. The study was: prompted by the imminent danger of lifestyle-related non-communicable diseases – including gastrointestinal tract cancers - to the health of the Surinamese community [22,23]. Data analysis was based on the number of histopathologically diagnosed malignancies and estimations of the demographic situation of Suriname in the period covered by this study

Each year, approximately 52 new Surinamese patients presented with a cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. When considering that per year roughly 300 Surinamese are newly diagnosed with cancer [36], it can be inferred that almost 1 out of every 6 of such patients suffers from a gastrointestinal tract malignancy. Nevertheless, placed against the background of international data, it can be assumed that the frequency of these neoplasms in Suriname is well below that reported for low-incidence areas of the world (around 25 per 100,000 per year) [1], and even farther from that noted for high-incidence countries (more than 50 per 100,000 per year) [1]. This suggests that Suriname (still) represents a lowrisk country for gastrointestinal tract malignancies, despite the alarming frequency of non-communicable diseases in the country [22,23].

The incidence rates of the most common gastrointestinal malignancies in Suriname - colorectal, stomach, and primary liver cancer – were consistent with this suggestion. Their frequencies in the country (2 to 5 case(s) per 100,000 populations per year) were well in line with those of 1.6 to 5.6 per 100,000 populations estimated for low-incidence regions in Middle Africa and South-Central Asia for colorectal cancer, Northern and Southern Africa for stomach cancer, and South-Central Asia and Northern Europe for primary liver cancer [1]. By comparison, incidence rates of these neoplasms in high-risk regions (Northern America, the majority of Europe, and Australia/ New Zealand; Eastern Asia, particularly China; and Eastern and South-eastern Asia, as well as large parts of Africa, respectively) are typically between 30 and 80 per 100,000 population [1].

Cancers of the pancreas, esophagus, gallbladder, small intestine, as well as anus and anal canal occurred in Suriname at rates of less than 1 per 100,000 populations per year. These values are also close to those reported for low-risk regions throughout the world. Examples of such areas are India; Western, Middle, and Northern Africa as well as Central America; and most of Northern Europe and the United States of America, with less than 3 cases of pancreatic, esophageal, and gallbladder cancer, respectively, per 100,000 per year [1,32,33]. For small bowel and anal cancer, the lowest rates (less than 0.5 and less than 0.1 case, respectively, per 100,000 population per year) have been reported in the Israeli Sabra [34] and Asian/Pacific Islanders in Hawaii [40], respectively. Incidentally, incidence rates associated with a high risk for pancreatic, esophageal, and gallbladder cancer are approximately 13, up to 34, and around 20, respectively [32,33,36,37]. These values have been reported for African American males in the United States of America [32]; the ‘esophageal cancer belt’ from northern Iran through the central Asian republics to North-Central China [36]; and women in Delhi (India) and Karachi (Pakistan) [33,37], respectively. Relatively high rates of small intestinal and anal cancer are seen in the Maori of New Zealand (up to 4 [34]) and African American women (about 0.74) [38]), respectively.

There were nearly as many males as females with colorectal or gastric cancer in Suriname. Such a sex distribution is not in agreement with reports mentioning that these malignancies occur approximately 1.5 times and twice, respectively, more often in men than in women [1]. This suggests that Surinamese females are at least exposed to some of the same risk factors for these cancer types as their male counterpart, including physical inactivity, overweight, and obesity [6,7]; unhealthy dietary habits [8,9,14,15]; excessive alcohol consumption [10]; and/or cigarette smoking [11,12,17]. This supposition may well hold true in light of the observations of the Pan American and the World Health Organization about the relative risk of Surinamese to develop non-communicable disorders [22,23], but it must be verified in comprehensive future studies. On the other hand, primary liver cancer was approximately twice more common in Surinamese men than in Surinamese women. This finding is consistent with the typical 2- to 4-fold male-over-female excess seen in most areas of the world [1,39,40], and has been tentatively attributed to gender-specific differences in exposure to risk factors: men are more likely than women to be infected with hepatitis B and C viruses, to consume alcohol and to smoke cigarettes, and to have a higher body mass index [40]. It is clear that this suggestion also needs to be further pursued.

The frequency of overall gastrointestinal tract cancers as well as that of the individual gastrointestinal tract malignancies – particularly colorectal, stomach, and liver cancer – increased markedly with older age. This trend is in accordance with the characterization of cancer as a group of diseases caused by multiple oncogenic mutations which act together or in sequence to initiate or promote carcinogenesis over many years. This has been described for colon cancer formation, which involves at least five successive stages, including hyperproliferation of the epithelium as a result of loss of the APC tumor suppressor; formation of an early adenoma due to increased genomic instability and the more rapid acquisition of mutations; formation of an intermediate adenoma due to activating mutations in the K-ras oncogene; formation of a late adenoma by loss of a SMAD gene and disruption of the growth inhibitory TGF-β signaling pathway; and the progression to a carcinoma by the loss of the p53 tumor suppressor and release of the cells from DNA damage- and stress-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [41,42].

Overall gastrointestinal tract cancers as well as most individual gastrointestinal tract cancers - particularly colorectal and stomach cancer – showed a clear predilection for Creoles rather than Hindustanis and Javanese. There is no satisfactory explanation for these observations. However, our previous studies [31,43,44] also revealed that malignancy is more common in Surinamese Creoles than in Surinamese Hindustanis and Javanese. Furthermore, in the United States of America, neoplastic disease has been found to be 10%, 50 to 60%, and more than twice more common in African Americans than in Caucasians, Hispanics and Asian/Pacific Islanders, and American Indians, respectively [45-47].

The exception to the above-mentioned pattern was primary liver cancer that was two to three times more common in Javanese than in Creoles and Hindustanis. A comparable situation has been observed in the United States of America, where this tumor is considerably more common in immigrants from areas where the hepatitis B virus is endemic (such as South-east Asian countries) when compared to other Americans [48, 49]. Individuals originating from these parts of the world have a relatively high rate of chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus, a major risk factor for liver cancer [16,50]. In addition, exposure to aflatoxins may contribute to the high incidence of liver cancer in those tropical areas of the world where contamination of food grains with the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus is common [51]. Whether these considerations may hold true for Suriname needs to be determined in future studies.

Summarizing, the results from this study suggest that Suriname is a low-risk region for gastrointestinal tract malignancies, even though these neoplasms are relatively common in the country. The most frequent histiotypes were colorectal, gastric, and primary liver cancer, which accounted together for approximately 85% of all gastrointestinal cancers diagnosed in the period covered by this study. The remaining 15% involved cancers of the pancreas, esophagus, gallbladder, anus and anal canal, as well as small intestine. The incidence of all gastrointestinal cancers overall and of all sub-sites increased with increasing age, and most – including colorectal and gastric cancer - were as common in males as in females, and had a predilection for Creoles rather than Hindustanis and Javanese. The main exception was primary liver cancer that was more common in men than in women and occurred more often in Javanese than in individuals from other ethnic backgrounds. Increased efforts should be dedicated to educational and awareness-raising programs aimed at the reduction of avoidable risk factors for non-communicable diseases including gastrointestinal tract malignancies.

5837

References

- Jemal, A., Bray, F., Center, MM., Ferlay, J., Ward, E., Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011; 61: 69-90.

- Wagner, AD., Grothe, W., Haerting, J., Kleber, G., Grothey, A., Fleig, WE. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24: 2903-9.

- Zhang, D., Fan, D. Multidrug resistance in gastric cancer: recent research advances and ongoing therapeutic challenges. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007; 7: 1369-78.

- Roxburgh, P., Evans, TR. Systemic therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: are we making progress? Adv Ther. 2008; 25: 1089-104.

- Bartlett, DL., Chu, E. Can metastatic colorectal cancer be cured? Oncology (Williston Park). 2012; 26: 266-75.

- García-Alvarez, A., Serra-Majem, L., Ribas-Barba, L., Castell, C., Foz, M., Uauy, R. et al. Obesity and overweight trends in Catalonia, Spain (1992-2003): gender and socio-economic determinants. Public Health Nutr. 2007; 10: 1368-78.

- Martín, JJ., Hernández, LS., Gonzalez, MG., Mendez, CP., Rey Galán, C., Guerrero, SM. Trends in childhood and adolescent obesity prevalence in Oviedo (Asturias, Spain) 1992-2006. Acta Paediatr. 2008; 97: 955-8.

- Ponz de Leon, M., Roncucci, L. The cause of colorectal cancer. Digest Liver Dis. 2000; 32: 426-39.

- Alexander, DD., Miller, AJ., Cushing, CA., Lowe, KA. Processed meat and colorectal cancer: a quantitative review of prospective epidemiologic studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2010; 19: 328-41.

- Ferrari, P., Jenab, M., Norat, T., Moskal, A., Slimani, N., Olsen, A. et al. Lifetime and baseline alcohol intake and risk of colon and rectal cancers in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC). Int J Cancer 2007; 121: 2065-72.

- Hannan, LM., Jacobs, EJ., Thun, MJ. The association between cigarette smoking and risk of colorectal cancer in a large prospective cohort from the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009; 18: 3362-7.

- Liang, PS., Chen, TY., Giovannucci, E. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2009; 124: 2406-15.

- Center, MM., Jemal, A., Smith, RA., Ward, E. Worldwide variations in colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009; 59: 366-78.

- Strumylaite, L., Zickute, J., Dudzevicius, J., Dregval, L. Salt-preserved foods and risk of gastric cancer. Medicina (Kaunas). 2006; 42: 164-70.

- Tsugane, S., Sasazuki, S. Diet and the risk of gastric cancer: review of epidemiological evidence. Gastric Cancer 2007; 10: 75-83.

- Parkin, DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 3030-44.

- Bertuccio, P., Chatenoud, L., Levi, F., Praud, D., Ferlay, J., Negri, E. et al. Recent patterns in gastric cancer: a global overview. Int J Cancer 2009; 125: 666-73.

- Ming, L., Thorgeirsson, SS., Gail, MH., Lu, P., Harris, CC., Wang, N. et al. Dominant role of hepatitis B virus and cofactor role of aflatoxin in hepatocarcinogenesis in Qiding, China. Hepatology 2002; 36: 1214- 20.

- El-Serag, HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in USA. Hepatol Res. 2007; 37 (suppl. 2): S88-94.

- General Bureau of Statistics. National accounts. Selected macro economic aggregates 2006-2010 (publication 283-2012/01). Paramaribo, Suriname: General Bureau of Statistics. 2012.

- General Bureau of Statistics. Suriname. Basic indicators 2012 – I (publication 284-2012/02). Paramaribo, Suriname: General Bureau of Statistic . 2012.

- Pan American Health Organization. Country profiles on noncommunicable diseases. Washington, DC, USA: Regional Office for the Americas of the World Health Organizatio . 2012.

- World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases country profiles 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organizatio . 2012.

- Usman, A., Mebrahtu, G., Mufunda, J., Nyarang›o, P., Hagos, G., Kosia, . et al. Prevalence of non-communicable disease risk factors in Eritrea. Ethn Dis. 2006; 16: 542-6.

- Peixoto Mdo, R., Monego, ET., Alexandre, VP., Souza, RG., Moura, EC. Surveillance of risk factors for chronic diseases through telephone interviews: experience in Goiânia, Goiás State, Brazil. Cad Saude Public. 2008; 24: 1323-33.

- Sugathan, TN., Soman, CR., Sankaranarayanan, K. Behavioural risk factors for non communicable diseases among adults in Kerala, India. Indian J Med Res. 2008; 127: 555-63.

- Punwasi, W. Doodsoorzaken in Suriname 2008-2009. Paramaribo, Suriname: Bureau Openbare Gezondhei . 2011.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organizatio . 2000.

- General Bureau of Statistics. Seventh general population and housing census in Suriname (publication 213-2005/02). Paramaribo, Suriname: General Bureau of Statistics/Census Offic . 2005.

- General Bureau of Statistics. Demographic data 2004-2010 (publication 276-2011/04). Paramaribo, Suriname: General Bureau of Statistic . 2011.

- Mans, DRA., Rijkaard, E., Dollart, J., Belgrave, G., Tjin, A., Joe, SS-L., Matadin, . et al. Differences between urban and rural areas of the Republic of Suriname in the ethnic and age distribution of cancer. A retrospective study from 1980 through 2004. Open Epidemiol J. 2004; 1: 30-5.

- Dhir, V., Mohandas, KM. Epidemiology of digestive tract cancers in India IV. Gall bladder and pancreas. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999; 18: 24-8.

- Randi, G., Franceschi, S., La Vecchia, C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cance. 2006; 118: 1591-602.

- Neugut, AI., Jacobson, JS., Suh, S., Mukherjee, R., Arber, N. The epidemiology of cancer of the small bowel. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998; 7: 243-51.

- Frisch, M., Goodman, MT. Human papillomavirus-associated carcinomas in Hawaii and the mainland. U.S. Cance. 2000; 88: 1464- 9.

- Gholipour, C., Shalchi, RA., Abbasi, M. A histopathological study of esophageal cancer on the western side of the Caspian littoral from 1994 to 2003. Dis Esophagu. 2008; 21: 322-7.

- Kapoor, VK., McMichael, AJ. Gallbladder cancer: an ‹Indian› disease. Natl Med J Indi. 2003; 16: 209-13.

- Behel, SK., MacKellar, DA., Valleroy, LA., Secura, GM., Bingham, T., Celentano, D . et al. HIV prevention services received at health care and HIV test providers by young men who have sex with men: an examination of racial disparities. J Urban Healt. 2008; 85: 727-43.

- Bosch, FX., Ribes, J., Díaz, M., Cléries, R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterolog. 2004; 127 suppl. 1): S5-16.

- Nordenstedt, H., White, DL., El-Serag, HB. The changing pattern of epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010; 42 suppl. 3): S206-14.

- Fearon, ER., Vogelstein, B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990; 61: 759-67.

- Ilyas, M., Straub, J., Tomlinson, IP., Bodmer, WF. Genetic pathways in colorectal and other cancers. Eur J Cance. 1999; 35: 1986-2002.

- Mans, DRA., Mohamedradja, RN., Hoeblal, ARD., Rampadarath, R., Tjin, A., Joe, SS-L., Wong, J, et al. Cancer incidence in Suriname from 1980 through 2000: a descriptive study. Tumor. 2003; 89: 368-76.

- Mans, DRA., Toelsie, JR., Bipat, R., Bansie, R., Vrede, MA. The incidence of head and neck cancers in the Republic of Suriname between the years 1980 and 2004. Translat Biomed. 2010; 1: :-5

- Ghafoor, A., Jemal, A., Cokkinides, V., Cardinez, C., Murray, T., Samuels, A, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002; 52: 326-41.

- Jemal, A., Murray, T., Samuels, A., Ghafoor, A., Ward, E., Thun, MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003; 53: 5-26.

- Parkin, DM., Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Pisani, P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005; 55: 74-108.

- Ward, E., Jemal, A., Cokkinides, V., Singh, GK., Cardinez, C., Ghafoor, A, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004; 54: 78-93.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta (GA), USA: American Cancer Society, Inc., Surveillance Research; 2011.

- World Health Organization. Viral hepatitis in the WHO South-east Asia region. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization – Regional Office for South-east Asia. SEA-CD-232; 2011.

- Liu, Y., Wu, F. Global burden of aflatoxin-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: a risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2010; 118: 818-24.