Eftihia Gesouli-Voltyraki1*, Maria Keramianaki2, Panagiota Kolofotia3, Georgia Fouka4, Viktoria Rizou5, Ioannis Kalemikerakis6, Dimitrios Karapoulios7

1Assistant Professor of Nursing, Technological Educational Institute (TEI) of Lamia

2Nurse, TEI of Lamia

3Nursing student, TEI of Lamia

4Assistant Professor of Nursing, Department of Nursing B, TEI of Athens

5General Practitioner, Health Centre of Tirnavos, Larisa, Regional Health Centre of Kipseli

6Lecturer Department of Nursing B, TEI of Athens

7General Practitioner, Health Centre of Litochoro, Pieria, Regional Health Centre of Platamonas

- *Corresponding Author:

- Gesouli Eftihia

Iroon Politechniou 38

PC 15773

Zografou, Athens

Greece

Tel: 210 7792366

Email: egesouli@teilam.gr

Keywords

Smoking, quit, nurse, intention.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) [1] has classified smoking in dependencies (Withdrawal symptoms from tobacco: Category Subdivision F17.2 in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). One of the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria on substances dependence is the continuous use of the substance despite knowledge that persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem is likely to be created or deteriorated by the substance itself. The severity of smoking dependence is reflected in the fact that only 1 / 3 of those who quit smoking without behavioral or pharmacological intervention remain abstinent for at least 2 days and less than 5% are eventually the ones who are successful in any effort of smoking cessation. The following facts are impressive examples of how powerful the addiction is: after lung cancer surgery almost half of patients resume smoking, 38% start to smoke again while they are still hospitalized following heart attack and 40% smoke again after laryngectomy [2]. It is also a fact that smokers, although in general are aware of the harmful effects of smoking, they consider it as a component of their personality and refuse to quit [3].

Pharmacological smoking cessation therapies are currently available, based on the administration of drugs with antidepressant properties, such as bupropion [4]. However, despite their perceived effectiveness, it is noted that counselling, coupled with the expressed desire of the smoker to quit, play the leading role. It has been shown that even if the health care professional devotes less than five minutes on counselling, e.g. in a visit to the clinic, this limited amount of time is beneficial [5]. This highlights the extremely important role that nurses and other health care professionals can play, apart from physicians, in the mobilization of the smoker to quit smoking. However, smoking rates among nurses and health care professionals in general, are considered as rather high. This raises questions on the success of the antismoking campaign. Indeed, as noted by other studies, Greece ranks first in the dismal percentage of smokers among European countries, with health care professionals keeping the primacy [6]. The aim of this study was to investigate the intention to quit smoking in nurses-regular smokers employed in primary and secondary health care.

Material and Method

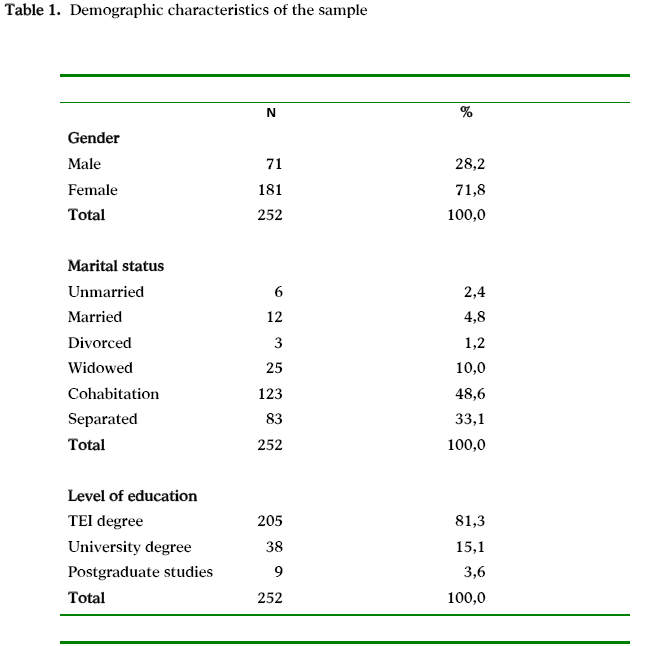

The study sample was 252 clinical nurses - regular smokers, taken from a total of 470 nurses employed in respective hospitals. Those who smoked every day, regardless of the number of cigarettes, were considered as regular smokers. The participants were nurses from Hospitals and Health Centers of Central Greece and Attica.

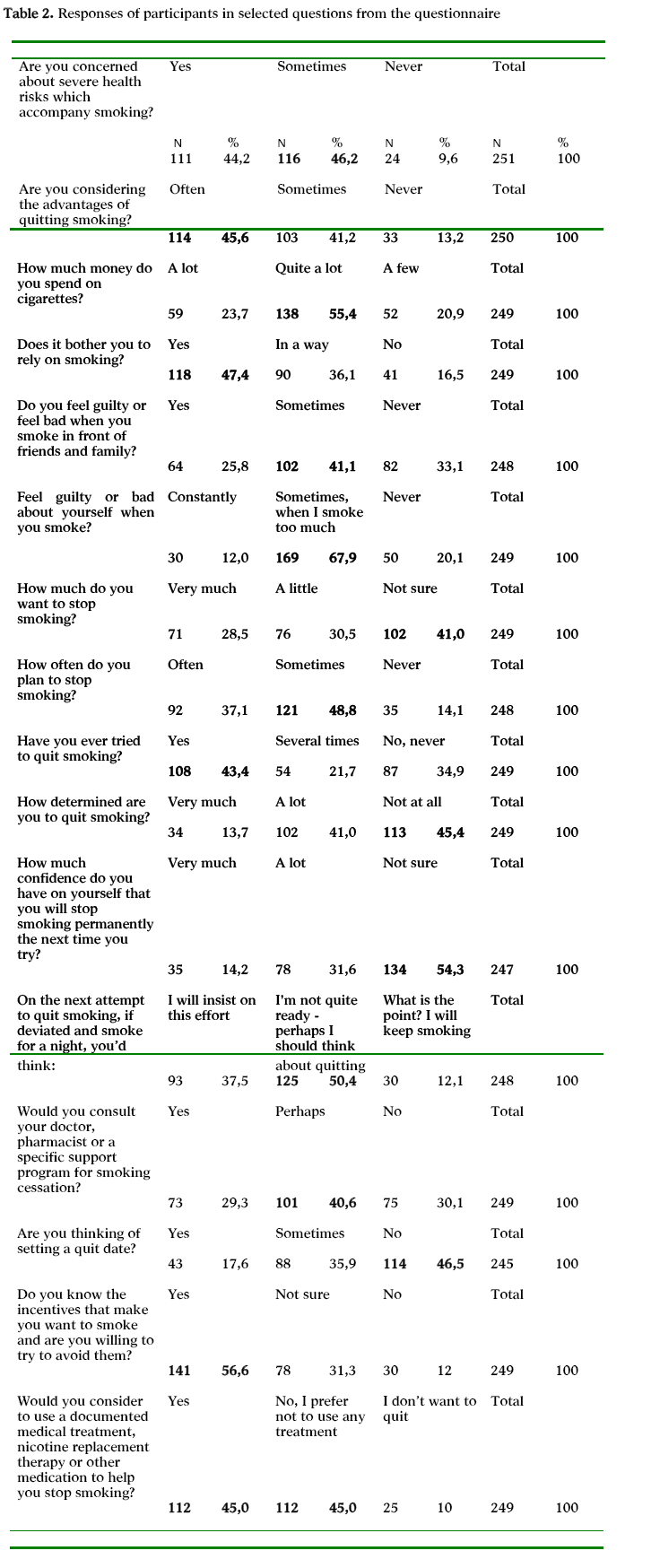

A questionnaire with closed-ended questions was used as a research tool, developed by the research team, based on questionnaires used for the same purpose in international surveys. It consisted of two parts: the first one included questions concerning demographic features and general health status, while the second part included 16 questions related to an individual’s intention to quit smoking and seeking medical assistance for this purpose. The answer to these questions comprises 3 possibilities with the following gradation: "Yes" and the equivalent answers, "A FEW TIMES", and "NO" and the equivalent answers.

Statistics

Initially, frequency tables were created for all variables and then variables were collapsed to the uniform presentation of results with emphasis on the group of smokers who responded quite positively on the intention to quit and seeking help from specialists. For the statistical analysis, x2 was applied with Yates correction for four-fold tables (Χ2c). The level of statistical significance was set at p=0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 17.0 software.

Results

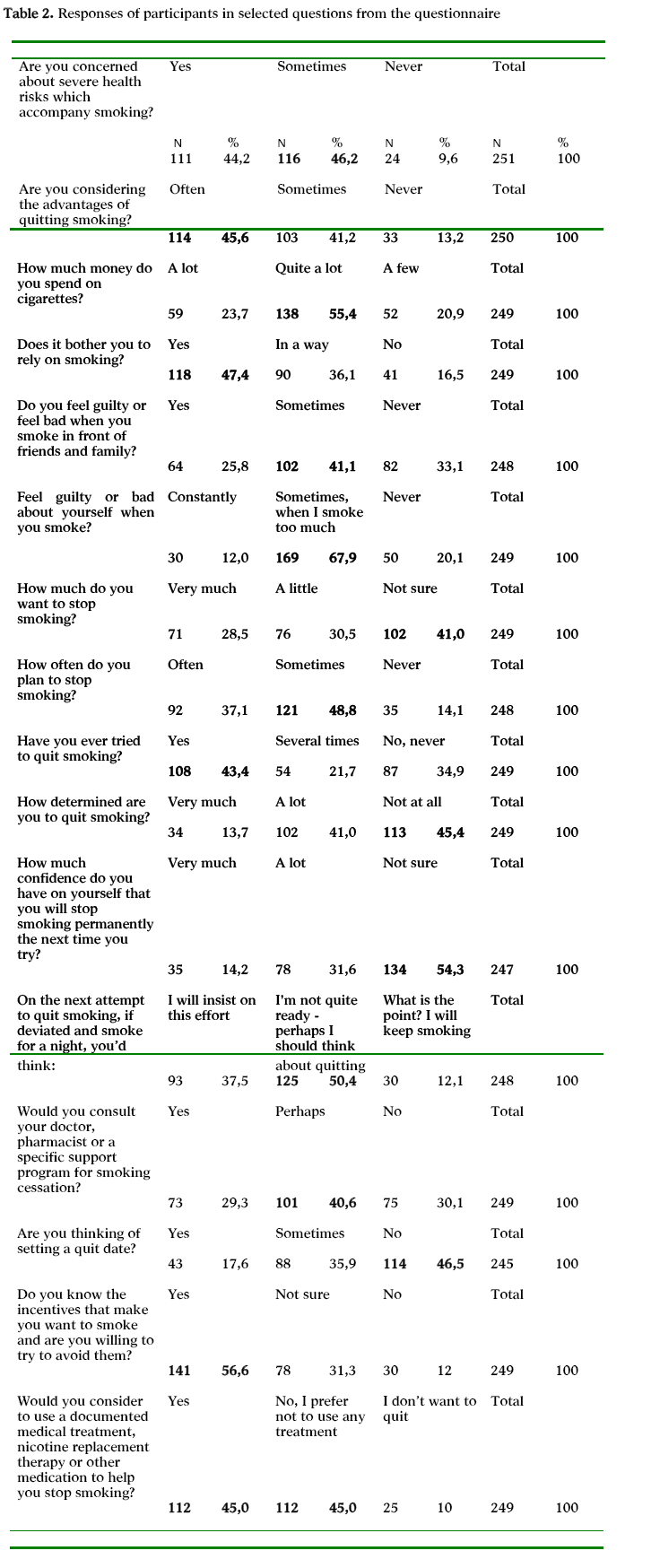

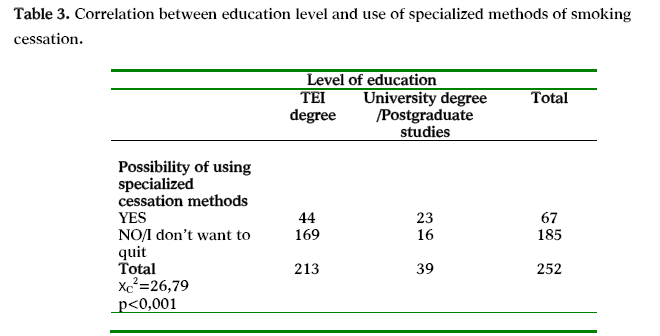

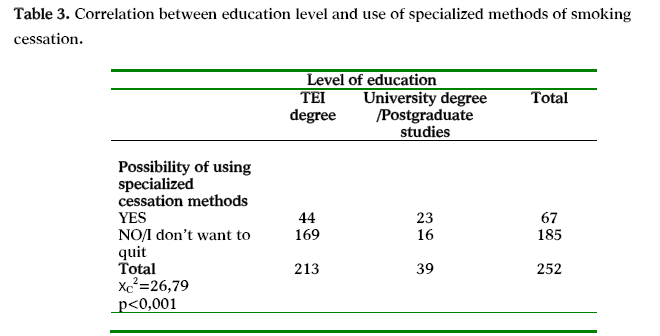

Women accounted for the 71.8% of the sample. 48.6% of all participants were married (Table 1). Nurses were mostly concerned about the severe risks associated with smoking (at a rate of 90.4%) and were thinking about the benefits of quitting (86.8%). Most of them thought that the cost of cigarettes was high (55.4%) and felt guilty when they smoked in front of friends and relatives, but also to themselves (79.1%). 59% was wishing, even slightly, to stop smoking and 85.9% was thinking about stopping. 65.1% had tried to quit in the past and 54.7% was somewhat or very determined to do so. 54.3% had no confidence in him/herself that he/she would finally stop smoking in the next attempt, while 50.4% appeared vulnerable to relapse. 69.9% would consult a specialist on methods to quit smoking, but 55% would not be using a documented medical treatment (Table 2). The majority of university graduates / postgraduate degree holders said they would use a documented medical help to stop smoking (Table 3).

Discussion

According to the results of this survey, the percentage of smokers within the health care professionals is quite high and close to 60%. Several studies find high rates of smokers among professionals in science disciplines [7,8]. The rates are particularly high among teachers, ranging between 40% and 46%, thereby testing the success of anti-smoking campaign in all educational levels [9]. Although recent research in the U.S. showed that 6% of physicians and 13% of nurses are smokers 10 -low rates, but not negligible- other surveys in western European countries raise these rates close to 45% [7]. According to the National Action Plan for Health, 31% of doctors and 57% of nurses on average state they are smokers, with women showing higher rates than men [8].

The percentages of female smokers have increased significantly in recent years, as a part of the grand total of smokers. For this reason, female smokers have attracted the interest of tobacco companies and health care professionals. Although the proportion of adults who smoke decreased steadily over the last 20 years in both sexes, research suggests that the incidence of smoking among women has probably risen. Women appeal more to psychological reasons to justify smoking, which they consider as a means of managing stress, a part of the socialization process, and a way to maintain a low body weight as well [11,12].

According to this investigation, although smokers are aware of the severe health risks and worry about them, are not likely to search for and turn to a documented medical treatment. It has been found that social pressure and cost are key reasons that can push a smoker to think about stopping, while the importance of his/her educational level is controversial [13]. It has been found that a high degree of alertness at all educational levels, in order to convince young people not to start or even quit smoking, and a redefinition of health care professionals training are necessary [14]. It is suggested that the anti-smoking campaign must be tailored to the educational level of smokers and focus on people with lower educational level [15].

Smoking is now considered a chronic relapsing condition, while treatment is often difficult. Among smokers, about 70% have thought about quitting at least once, 35% try to quit smoking at least once a year, but only 6% of them manage to maintain abstinence from smoking [16,17]. It is noted that several conditions can trigger once again the need for tobacco, even after long periods of abstinence. These may be related to the individual need for control of weight gain, control of psychiatric disorders (mood changes, reduction of stress) and chronic pain.

The importance that smokers attribute to the unbearable cost of their custom is reflected in the overall burden that smoking puts on society. Beyond the devastating consequences on health which are already known, smoking comprises a significant burden on family budget and exerts indirect economic effects on the entire community. The overall economic burden of smoking is related to the loss of working hours due to illness (even from non-malignant diseases such as chronic bronchitis which is common in smokers), the burden on pension funds from hospitalization, early retirements and withdrawal of productive workforce from the economy. Every smoker who consumes daily a package worth of 3 €, spends every year 1100 € and approximately 50.000 € for all his/her life. A UK survey showed that the total annual costs attributed to smoking are approaching the amount of 5 billion pounds. Smoking is responsible for 100,000 deaths annually, which account for 30% of deaths in men and 11% of deaths in women, approximately [18,19]. Although many studies focus on the incidence of smoking and its harmful effects, few studies deal with the profile of the smoker and his/her intention to quit. This study provides information about the personality of the smoker and his/her world view, which will help the health care professional to understand his/her behavior and help him/her in his/her effort to stop smoking [20]. Just because it is a dependence that we are dealing with, the strengthening of smoking cessation clinics, and the implementation of strict measures taken in recent years by the state, must be supported. Perhaps the sanctions against health care professionals who smoke should be particularly stringent.

Conclusions

Outlining the profile of the health professionals who smoke and especially women, we observe that despite their desire to quit, manifesting by a large percentage of smokers, the appeal to documented medical cessation methods remains uncertain. The social causes, which in many cases led to the initiation of smoking, appear to be the likely motive for the cessation, rather than quitting due to the awareness of harmful consequences, with which health care professionals are also well familiarized. The reservation expressed towards drug treatment makes the need for proper public information on smoking cessation clinics and assistance for discontinuation offered by pharmaceutical substances even more urgent.

3188

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Tobacco or health: a global status report. Geneva: WHO. 1997.

- Singer S, Keszte J, Thiele A, Klemm E, Täschner R, Oeken J, et al. [Smoking behaviour after laryngectomy]. Laryngorhinootologie 2010; 89(3):146-50.

- Marselos M, Fragides Ch. Knowledge and attitudes of Greek pupils towards smoking Mat Med Greca 1989; 17(2):101-110 ( article in Greek)

- Balbani AP, Montovani JC. Methods for smoking cessation and treatment of nicotine dependence. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2005; 71(6):820-7.

- Okuyemi KS, Nollen NL, Ahluwalia JS. Interventions to facilitate smoking cessation. Am Fam Physician 2006; 74(2):262-71.

- Vardavas CI, Kafatos A. Greece's tobacco policy: another myth? Lancet 2006; 367(9521):1485-6.

- Smith DR, Leggat PA. A comparison of tobacco smoking among dentists in 15 countries. Int Dent J 2006; 56(5):283-8.

- Sichletidis LT, Chloros D, Tsiotsios I, Kottakis I, Kaiafa O, Kaouri S, et al. High prevalence of smoking in Northern Greece.Prim Care Respir J 2006; 15(2):92-7.

- Hughes JR. The future of smoking cessation therapy in the United States. Addiction 1996; 91(12):1797-802.

- Beletsioti - Stika P. Woman and smoking NOSILEFTIKI 2006; 45(4):450–457.

- Gritz ER, Nielsen IR, Brooks LA. Smoking cessation and gender: the influence of physiological, psychological and behavioural factors. J Am Med Womens Assoc 1996; 51(1-2):35-42.

- Aubin HJ, Peiffer G, Stoebner-Delbarre A, Vicaut E, Jeanpetit Y, Solesse A, et al. The French Observational Cohort of Usual Smokers (FOCUS) cohort: French smokers perceptions and attitudes towards smoking cessation. BMC Public Health 2010; 10:100.

- Chatkin J, Chatkin G. Learning about smoking during medical school: are we still missing opportunities? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009; 13(4):429-37.

- Willemsen MC, Van der Meer RM, Schippers GM. Smoking cessation quitlines in Europe: matching services to callers' characteristics. BMC Public Health 2010; 10:770.

- Hughes JR, Gulliver SB, Fenwick JW, Valliere WA, Cruser K, Pepper S, et al. Smoking cessation among self-quitters. Health Psychol 1992; 11(5):331-4.

- Anderson JE, Jorneby DE, Scott WJ, Fiore MC. Treating tobacco use and dependence: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for tobacco cessation. Chest 2002; 121(3):932-941.

- Shearer J, Shanahan M. Cost effectiveness analysis of smoking cessation interventions. Aust N Z J Public Health 2006; 30(5):428-34.

- Nicotine Addiction in Britain: a report of the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians. London:Royal College of Physician; 2000.

- Pérez-Stable EJ, Fuentes-Afflick E. Role of clinicians in cigarette smoking prevention. West J Med 1998; 169(1):23-9.