Keywords

Nurses; Health services administration; Quality of health care; Organizational culture; Crete

Introduction

Organizational culture is a multidimensional concept that has emerged independently in several disciplines ranging from social anthropology to organizational psychology. Ravasi and Schultz described organizational culture as a set of shared assumptions that guide what happens in organizations by defining appropriate behavior for various situations [1].

Organizational culture (OC) includes norms, systems, vision, assumptions, beliefs, philosophy, and values that hold together, and is expressed in its self-image, affects the way people and groups interact with each other, with clients, and future expectations [2-4]. According to Cooke and Rousseau, an organizational culture can be defined as a set of specific behaviors, rules or norms (i.e. behavioral norms), which members believe they should adopt to survive and work within such an organization. These behavioral patterns can be productive or not and can lead to behaviors and attitudes that determine how the members approach their work and interact with each other [2]. In the professional field of health care, organizational culture has been positively associated with elements of organizational performance that contribute to quality of services, such as nursing care, job satisfaction, patient and personnel safety, personnel turnover rate and change of management process [5-9]. Furthermore, organizational culture has also been positively associated with financial performance [10-12].

Nurses, as the health care professionals most actively engaged in direct patient care, especially those working in a hospital setting, are an important professional group that can influence the overall culture of a health organization positively or negatively [13,14].

Accordingly, the culture of a health care organization can be a powerful characteristic that affects particularly hospital nurses’ work environment, and enhances hospitals’ ability to adapt to environmental change [15].

However, establishing the exact relationship between personnel performance, the type of culture that governs an organization and success or failure in achieving its objectives has not been simple [16]. In addition, in complex organizations such as health services organizations, multiple professional groups might present multiple cultures and the interdependent aspects of each subculture within a large organization might not favor planned changes [2,17,18].

Nurses in the health care system of Crete, which is identical to the Greek NHS on a smaller scale, are facing the challenges of increasing demands on health care services in a highly centralized and doctor-centered health system, which minimizes the professional autonomy of nurses and increases hindrances to interdisciplinary collaboration [19].

Diagnostic assessment of nurses’ organizational culture can provide an appreciation of the existing cultural traits within an organization and their effectiveness in promoting desirable organizational processes and outcomes, and may identify areas of strengths and weaknesses of nurses within an organization or a health care system.

Aim

The aim of the study was to identify the organizational operating culture in total and within levels of the public health care organizations in Crete as perceived by nurses.

Methods

The current descriptive comparative study was conducted in Crete (Greece). The study was carried out at the five General Public Hospitals (secondary health level), one University Hospital (tertiary health level) and at the seven of the fourteen public Health Centers (primary health level), which were randomly selected. A multistage random sampling method was applied. The selfcompleted questionnaire (the Organizational Culture Inventory® Greek Ed.) was administered in the workplace following their oral informed consent after complete description of the study. 120 anonymous questionnaires were distributed to nurses and 81 were returned completed, resulting in a satisfactory response rate (68 %). Ethical approval was obtained from the Research and Bioethics committees of the University Hospital of Crete.

Instrument

The Organizational Culture Inventory® (OCI®) is an integral component of Human Synergistics’ International multi-level diagnostic system for individual, group, and organizational development [20-24].

The OCI® measures “what is expected” of members of an organization—or, more technically, behavioral norms and expectations which may reflect the more abstract aspects of culture such as shared values and beliefs. The OCI® contains 120 items instructing respondents to rate: “To what extent are people expected or implicitly required to …” (for example “think ahead” or “plan”), with the response options on a Likert 5-scale rating (1 = not at all; 2 = to a slight extent; 3 = to a moderate extent; 4 = to a great extent; 5 = to a very great extent) [24].

It measures 12 types of culture styles (behavioral norms) which are organized into three general clusters (Constructive, Passive/ Defensive and Aggressive/Defensive) [20-24]. The Constructive styles are highly effective and promote individual, group, and organizational performance. In contrast, the Aggressive/ Defensive styles have an inconsistent and potentially negative impact on performance and the Passive/Defensive styles consistently detract from overall effectiveness [20-24].

In the Constructive cluster, members are encouraged to interact with people and approach their tasks in ways that will help them to meet their higher-order satisfaction needs. The Constructive cluster includes the Achievement culture style, in which members are expected to set challenging but realistic goals; Self Actualizing style, in which members are expected to enjoy their work, develop themselves and take new and interesting activities; Humanistic style, in which members are expected to be supportive and constructive; and the Affiliative culture style, in which members of organizations are expected to be friendly, cooperative and sensitive to the satisfaction of their work group [20-24].

In a Passive/Defensive cluster, members believe they must interact with people in ways that will not threaten their own security. The Passive/Defensive cluster includes: the Approval culture style, in which members are expected to agree with and be liked by others; Conventional culture style, in which members are expected to follow the rules and make a good impression; Dependent (members are expected to do what they are told and clear all decisions with superiors); and Avoidance culture style, in which members are expected to shift responsibilities to others and avoid being blamed for a mistake [20-24].

In the Aggressive/Defensive cluster, members are expected to approach tasks in forceful ways to protect their status and security. It includes the Oppositional culture style, in which members are expected to be critical, oppose others' ideas and undertake low risk decisions, Power culture style, in which members are expected to take charge and control subordinates, Competitive culture style (members are expected to compete with and work against their colleagues) and the Perfectionist culture style, in which members are expected to avoid mistakes but also to work long hours engaged in narrowly defined objectives [20-24].

The OCI® instrument has been tested for reliability and validity and appears to be a dependable means of assessing the normative aspects of culture. It has also been found to have satisfactory levels of internal consistency, as well as convergent and discriminant validity [4].

The Organizational Culture Inventory® Greek Ed. (OCI®) was used for the measurement of current operating organizational culture in the specific health care organizations. The OCI® is recognized as one of the most widely used and thoroughly researched organizational surveys in the world [20-24].

The Greek modified version has also been found to have satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach alpha) of the 12 culture styles of OCI® ranging from 0.665 to 0.914 while the overall consistency of OCI® was α=0.900 [25,26].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Mean scores for each of the of the twelve cultural styles were converted to percentile scores based on the average (mean) responses of all members who completed the OCI® and analyzed by Human Synergistics International, the copyright holder of the survey instrument.

The cluster that best describes the operating culture of nurses is the one that has the highest average percentile score (i.e. the highest score when the percentile scores of the four styles within the cluster are averaged together). The results for the total group and per level of health care of nurses participating in the current study were plotted on a circular diagram or circumplex, which is used to describe operating cultures. The circumplex is generated by comparison to a norming sample, which comprises the results of 921 organizations that Human Synergistics approached as part of their research [24].

Analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample

The sample consisted of eighty one nurses (n=81), 12.3 % male and 87.7 % female. The majority of the participants were between 30 and 49 years old (72.8 %). As regards their level of education, 4.9 % were holders of an MSc or PhD. The majority of the respondents (50.6 %) had been within the organization for more than 10 years, and were almost equally distributed in Health Centers, General Hospitals and the University Hospital (Table 1).

Table 1: Descriptive characteristics of total group (n=81).

| |

Males |

Females |

Total |

| Characteristic |

n(%) |

| Gender |

10(12.3) |

71(87.7) |

81 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Age, years |

20 – 29 |

1(10.0) |

17(23.9) |

18(22.2) |

| |

30 – 39 |

5(50.0) |

33(46.5) |

38(46.9) |

| |

40 – 49 |

4(40.0) |

17(23.9) |

21(25.9) |

| |

50+ |

- |

4(5.6) |

4(4.9) |

| Education level |

secondary (e.g. Lyceum) |

- |

6(8.5) |

6(7.4) |

| |

secondary with specialization (e.g. paramedic training) |

- |

7(9.9) |

7(8.6) |

| |

higher

(e.g. university/technological school) |

8(80.0) |

56(78.9) |

64(79.0) |

| |

higher with specialization

(e.g. MSc or/and PhD) |

2(20.0) |

2(2.8) |

4(4.9) |

| Experience, years |

less than 1 year |

- |

3(4.2) |

3(3.7) |

| |

1 to 4 |

3(30.0) |

5(7.0) |

8(9.9) |

| |

5 to 6 |

1(10.0) |

17(23.9) |

18(22.2) |

| |

7 to 10 |

- |

11(15.5) |

11(13.6) |

| |

10+ |

6(60.0) |

35(49.3) |

41(50.6) |

| Health Care levels |

Primary |

2(20.0) |

25(35.2) |

27(33.3) |

| |

Secondary |

1(10.0) |

24(33.8) |

25(30.9) |

| |

Tertiary |

7(70.0) |

22(31.0) |

29(35.8) |

Chi-square test. No significant differences were found between genders.

Measurement of nurses’ organizational culture

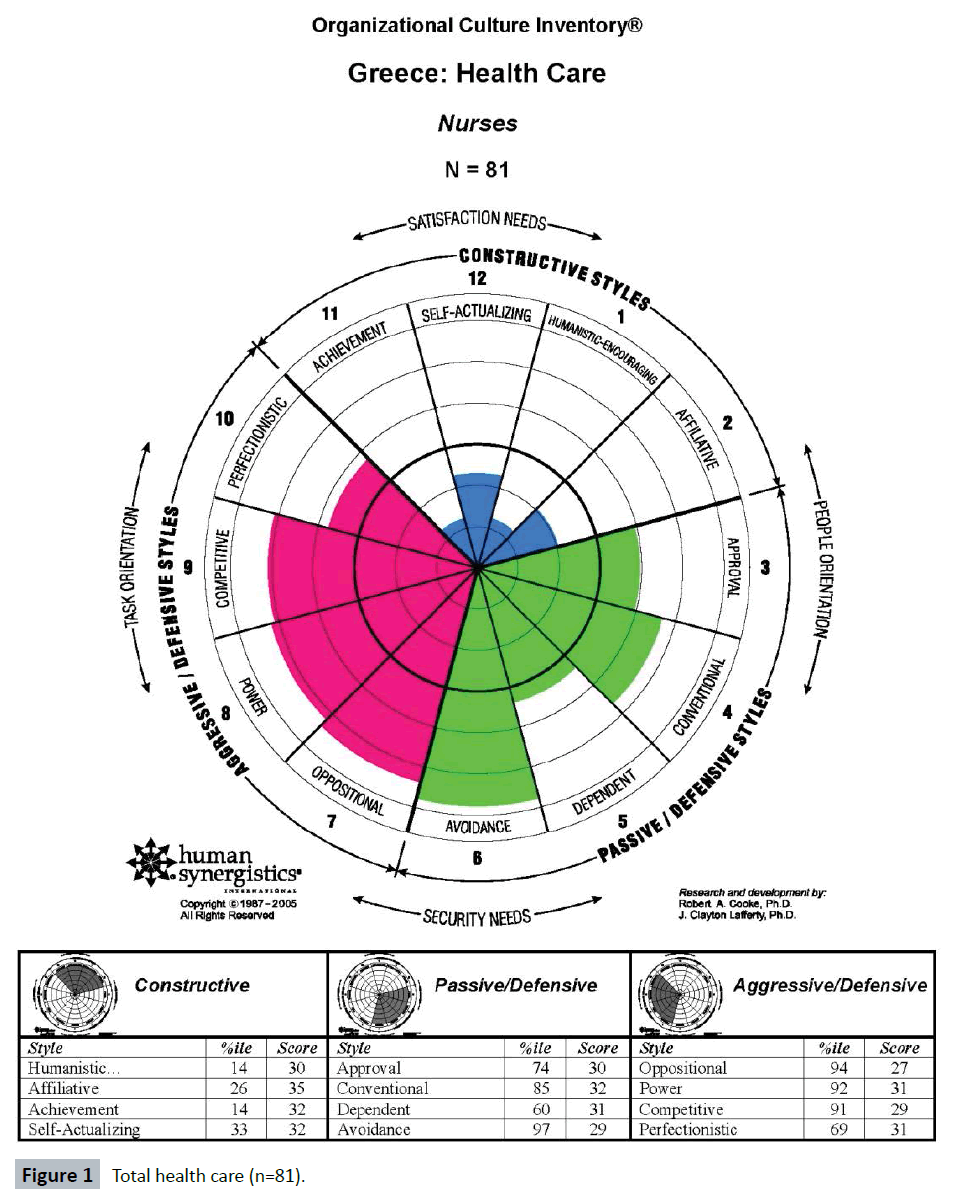

The cluster that best describes nurses’ perception of operational culture in total and within health care level is the Aggressive/ Defensive cluster, being the one that has the highest average percentile score (total 86.5 %ile, primary 85.25 %ile, secondary 87.75 %ile and tertiary 84.25 %ile) (Figure 1, total culture). With respect to the specific culture styles in total, the primary style is Avoidance (97 %ile) and the secondary style is Oppositional (94 %ile).

Figure 1: Total health care (n=81).

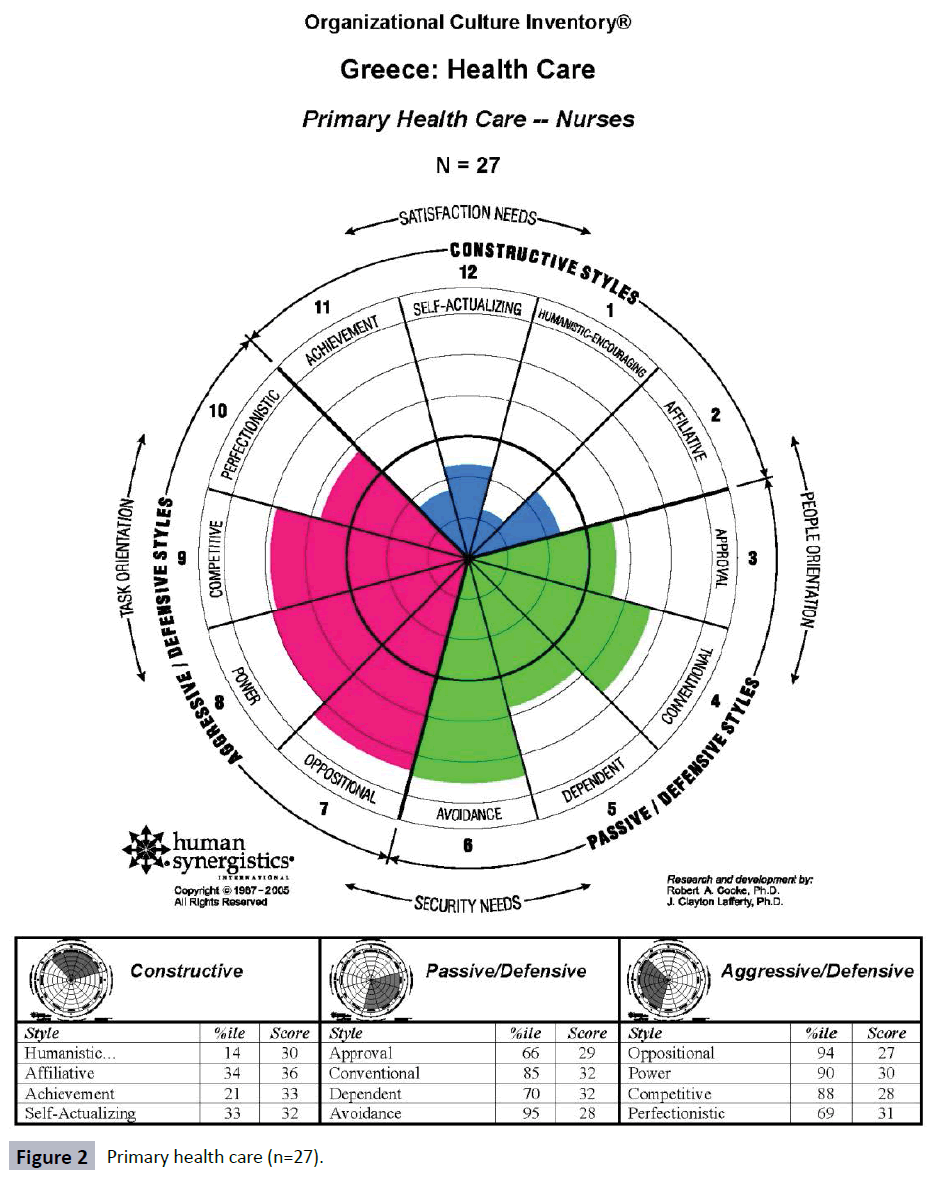

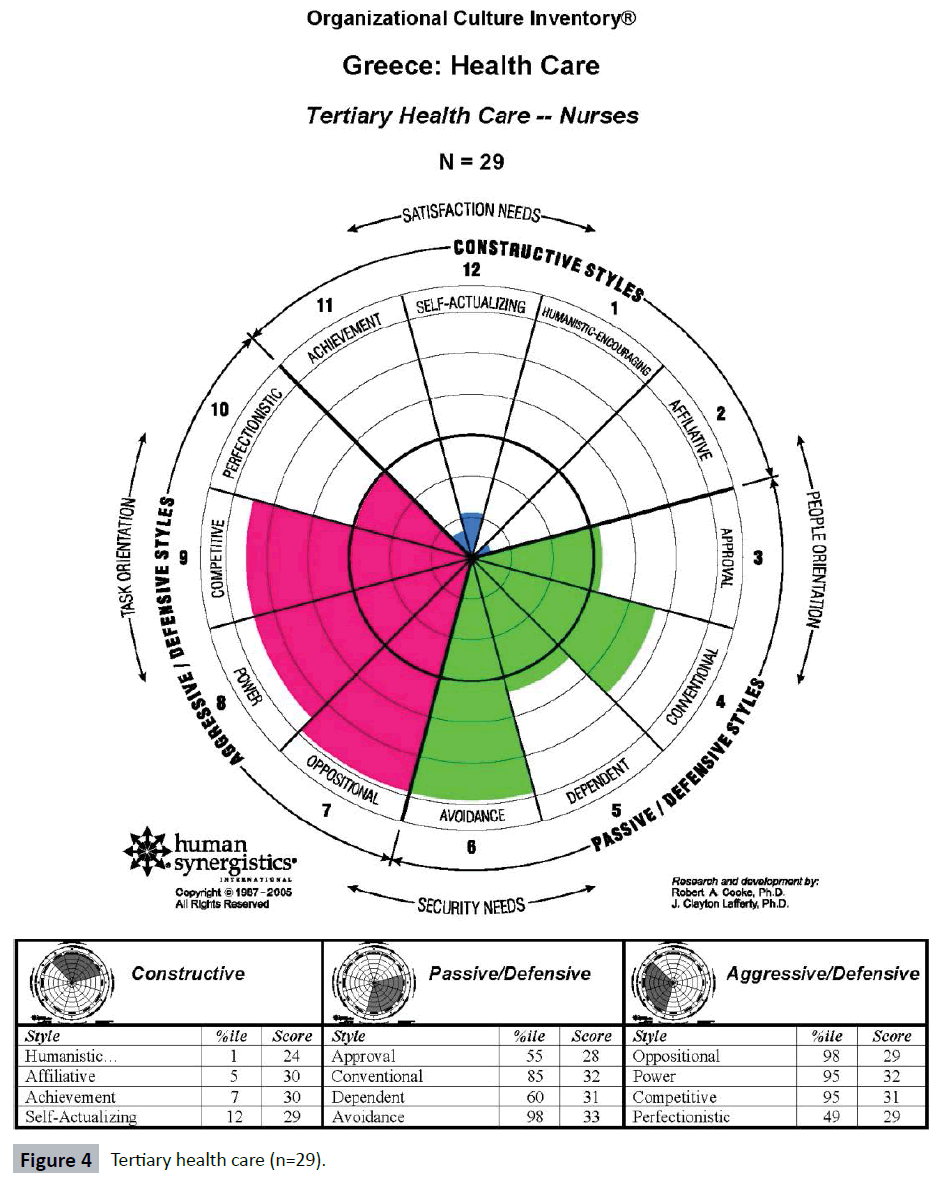

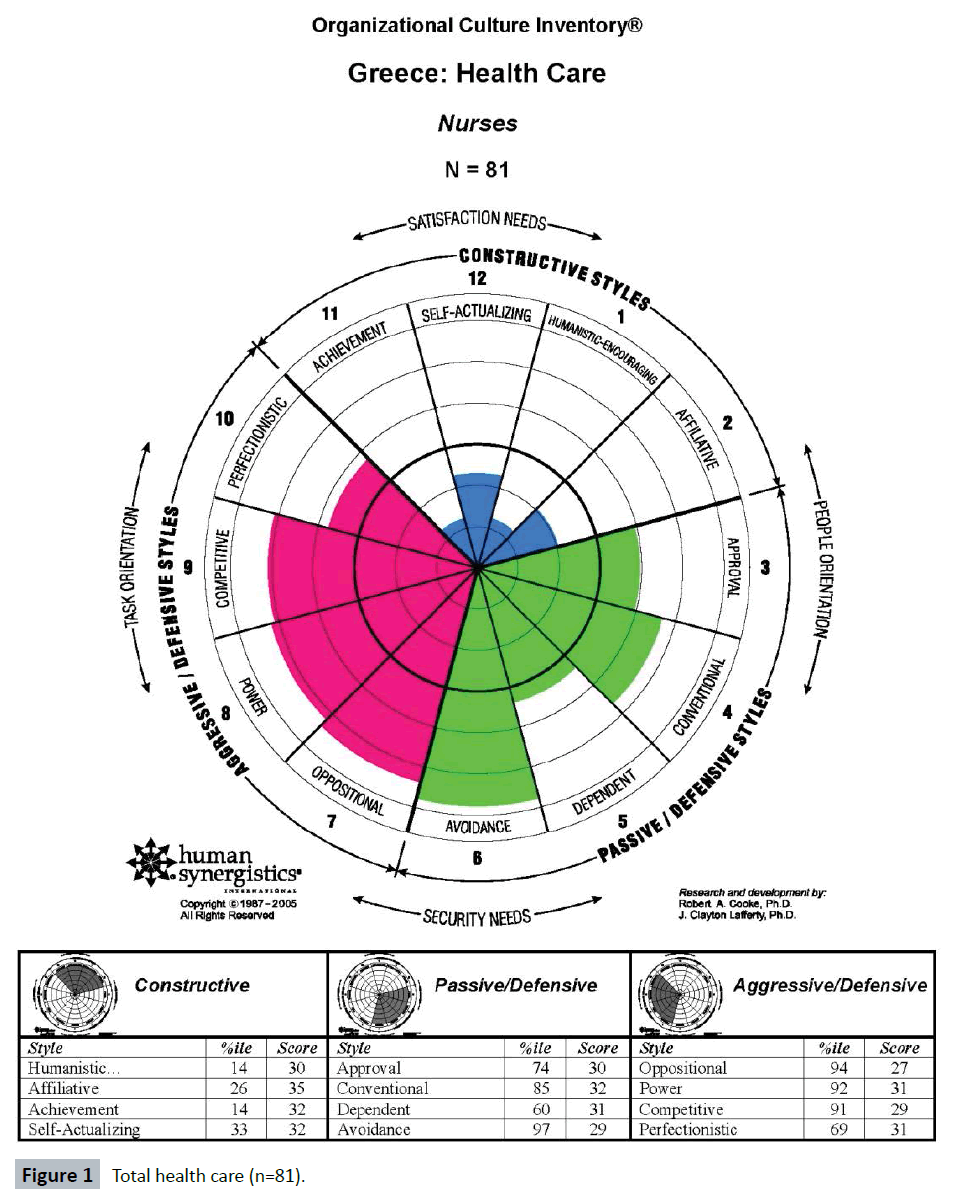

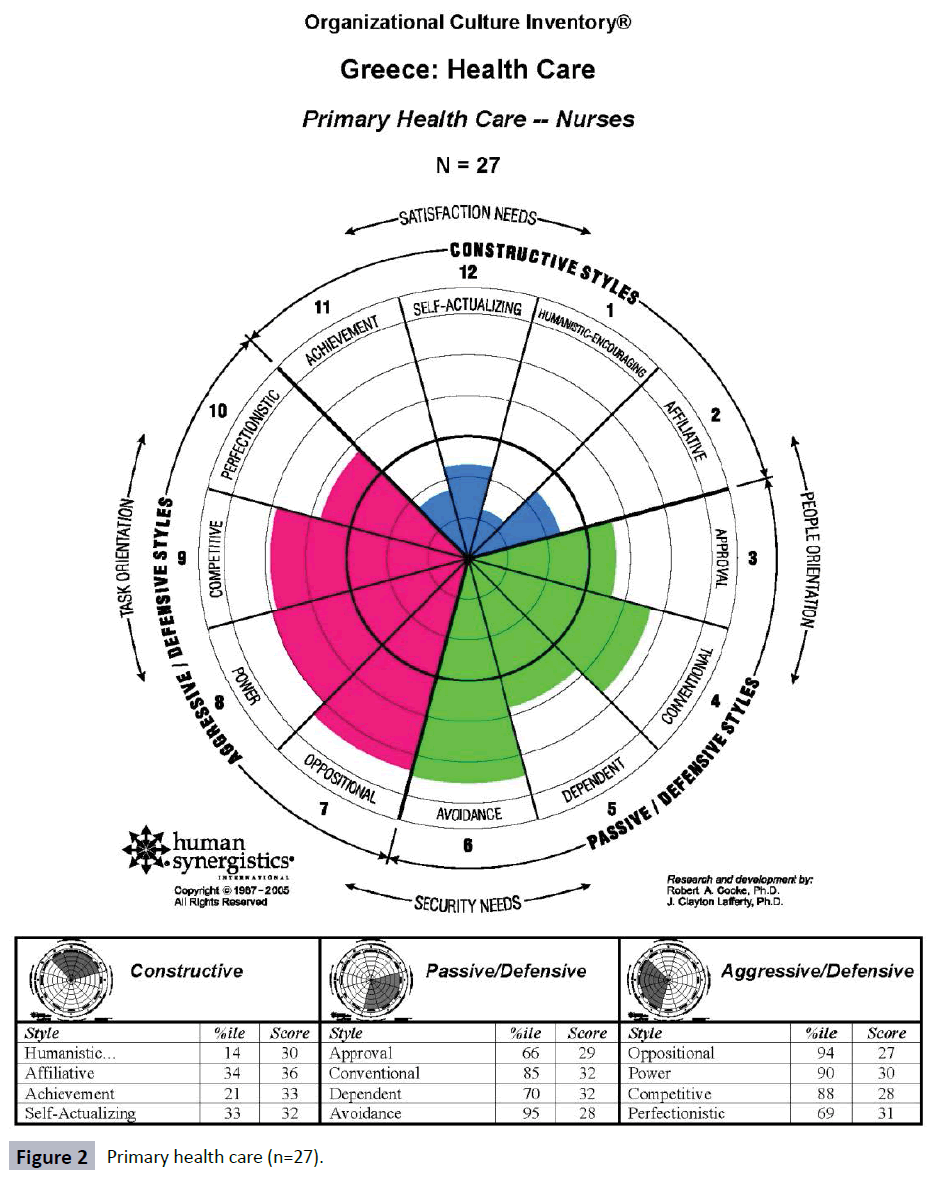

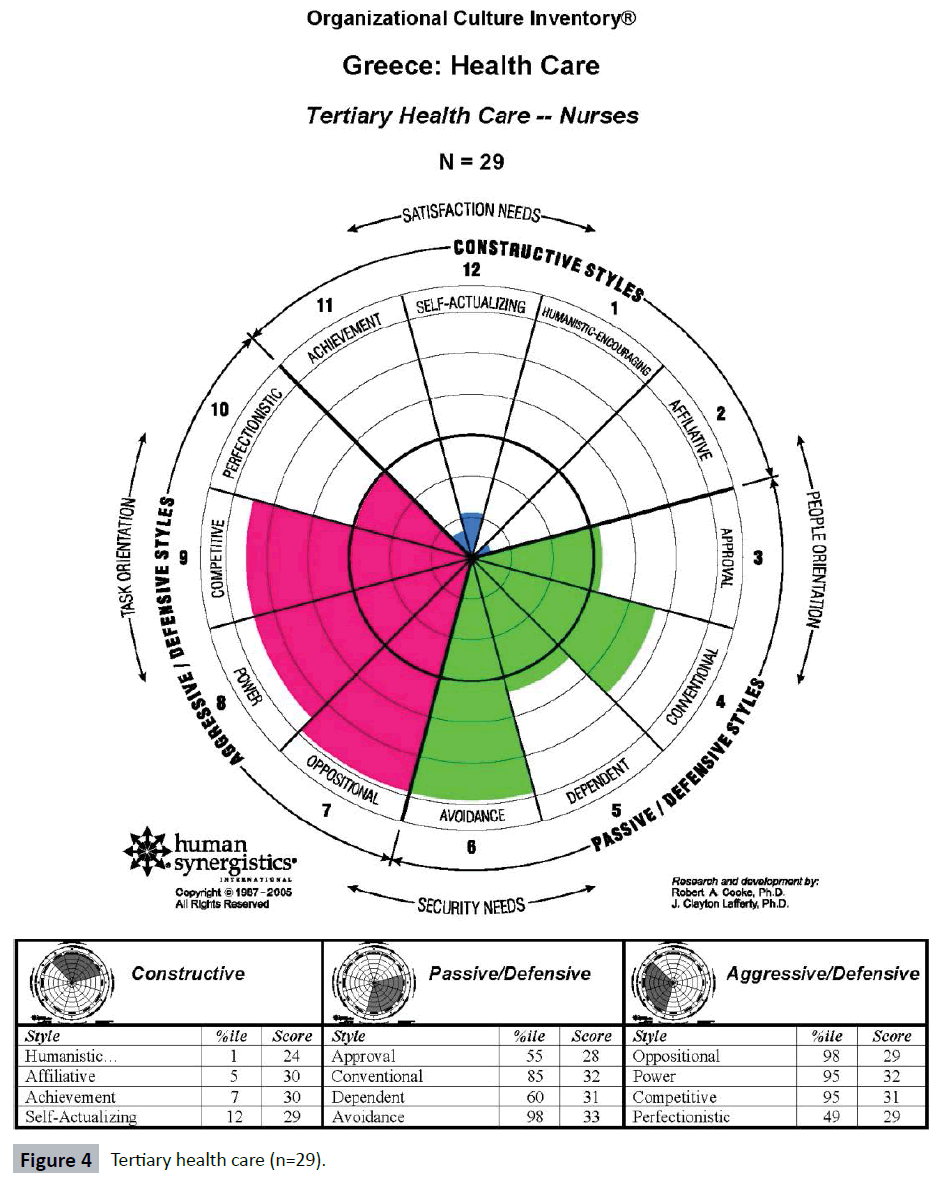

Nevertheless, the analysis of the 12 culture styles of nurses per health care level revealed that, in Health Centers, Avoidance is the primary culture style (95 %ile) and Oppositional is the secondary culture style (94 %ile) (Figure 2). With respect to the nurses working in General Hospitals, Power is the primary culture style (95 %ile), followed by Avoidance (92 %ile) as secondary culture style (Figure 3). Concerning the University Hospital, Oppositional and Avoidance (98 %ile) are the primary culture styles perceived by nurses, followed by Power and Competitive (95 %ile) as secondary styles (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Primary health care (n=27).

Figure 3: Secondary health care (n=25).

Figure 4: Tertiary health care (n=29).

Finally, nurses overall, but mainly in the University Hospital, present the lowest score in the Constructive culture (6.25 % ile) (Figure 4).

Discussion

Subgroups within organizations develop their own culture types and impact positively or negatively on the performance of an organization [2]. As health care systems are confronted with increasing demands to participate in a wide range of quality improvement activities, they are reliant on nurses to help address these demands. Nurses, as the health care professionals most actively engaged in direct patient care, especially those working in a hospital setting, are an important professional group that can influence the overall culture of a health organization positively or negatively [13,14]. However the results of the current study revealed that nurses' perception of organizational culture in the health organizations of Crete, independently of health care level, is directly related to the Aggressive/Defensive culture, whereas Constructive styles are the least present.

The Aggressive/Defensive culture encourages members to behave competitively and adopt a controlled and superior attitude, even if they lack the necessary knowledge, skills, abilities and experience, in order to protect their status and sense of security [24]. In this type of culture, the constant pressure results in a situation of displaying examples of individual members’ excellence and expertise, at the expense of teamwork and motivation [23,24]. Aggressive/Defensive norms are negatively correlated with employee job satisfaction and positively correlated with stress. Thus, Aggressive/Defensive norms prevail in those organizations most in need of cultural change [23].

The results of the current study contradict the results of other related studies showing nurses as the main subgroups within health care settings, characterized mainly by Constructive elements of organizational culture [25-29]. Nevertheless, other studies found that nurses, independently of the theoretical framework adapted, present Passive/Defensive or Aggressive/ Defensive scores, especially in public health organizations with high levels of hierarchy or bureaucracy [17,30]. Seago, in a study of organizational culture in acute-care hospitals at the nursing unit level, found that the cultures of the institutions tended to be constructive, but there were a substantial number of nurses who had passive-defensive or aggressive-defensive scores [31]. In a study attempting to identify the organizational culture and subcultures within Greek public hospitals using the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP), the results suggested that the two most prominent characteristics were aggressiveness and supportiveness, whereas the two least prominent were decisiveness and team orientation. However, the results should be compared with caution, as the OCP instrument is based on a somewhat different theoretical background [17].

Nurses’ perception of Aggressive/Defensive culture within Cretan health organizations may be an “expected” result, since managers cannot infuse a common pattern of values among them, as they are effectively unable to shape human resource policies and practices [17,25,26]. Greek Public Hospitals and Health Centers continue to face major organizational problems such as reduced staffing, lack of employee evaluation, and lack of motivation and reward systems [17,19,32]. Thus the system relies heavily on employee willingness to contribute to the effective and quality performance of the health organizations. In parallel, Health Centers are understaffed while covering large populations [32]. This may be the main cause of conflicts, encouraging a culture of competition among nurses, rather than one of cooperation. Human resource management in the public health care sector is highly centralized and bureaucratic. Consequently, recruitment and selection of employees is controlled by the central authorities who are unable to ensure person-organization fit, motivation or reward systems [17,19,32]. Recent studies in Greek Public Hospitals support the findings of the present study and reveal employees’ notion that taking advantage of opportunities, willingness to experiment and risk-taking behaviors were the values least stressed by their organization [33], and thus team orientation and decisiveness are not valued characteristics of public hospitals [17,33]. Those characteristics of behavioral styles drive nurses to protect their status within the organization and in relation to the other professional subgroups, encouraging them to behave competitively at the expense of teamwork and motivation, displaying culture styles referred to Aggressive/ Defensive culture.

In a study designed to test hypotheses regarding the impact of culture in 60,900 respondents affiliated to various organizations [34], results illustrated that dysfunctional Defensive styles have a profound negative impact on both individual and organizational level performance drivers. Additionally, while Defensive behaviors (Passive and Aggressive) are negatively associated with role clarity, “fit” and job satisfaction, they are positively associated with communication, ambiguity and behavioral conformity [34].

Moreover, organizations with an Aggressive/ Defensive culture tend to place relatively little value on people and promoting internal competition [2,20,24]. In a qualitative study using a focus group design, in a teaching hospital in the region of Thessaloniki, Greece, health care professionals saw themselves as the victims of the health care system and had a pervasive sense of powerlessness [35].

In agreement with the results of the above study, a European cross- sectional survey carried out in twelve European countries, data from 24 Greek public general hospitals revealed a particularly high level of nurse burnout, dissatisfaction, and intention to leave, nearly half described their wards as providing poor or fair quality of care, and almost one-fifth gave their hospitals a poor or failing safety grade [36].

The analysis of the 12 culture styles per health care level reveals that Avoidance is encouraged by all health organizations either as primary or as secondary style, whereas Oppositional is present as secondary culture style in Health Centers and as primary culture style in the University Hospital.

Concerning culture styles perceived by nurses, the only difference to the displayed current result pattern seems to be in the total of health care organizations in Crete and specifically in Power, as primary style in General Hospitals and as secondary style along with Competitive in the University Hospital. This is only to be expected, as types of cultural norms characterizing complex bureaucratic organizations which operate in fast-paced environments and emphasize traditional approaches to quality control [24]. The constant pressure to maintain the facade of perfection and expertise comes at the expense of member’s health, motivation, teamwork, and the way customers are treated [24]. Aggressive/Defensive behaviors concerning nurses working in the public health sector in Crete are promoted by factors involving goals settings, job insecurity and disempowerment at the member/job level and use of power at the manager/unit level, as well as cultural values and disrespect for members at the organizational level [24,26].

Avoidance, as a culture style present at all levels of health care organizations, encourages the most security-oriented behaviors. Avoidance culture characterizes organizations that fail to reward success but nevertheless punish mistakes. This negative reward system leads members to do nothing, to resist change, to shift responsibilities to others and to avoid any possibility of being blamed for a mistake. Such organizations are unlikely to move in new directions, learn from mistakes or adapt to changes in their competitive environment [20,21,24].

The strict chain of command and line of reporting with deep vertical structures reflecting varying levels of administrative controls in Greek health organizations, along with the failure to reward success but nevertheless punish mistakes, may drive Cretan nurses to be unwilling to make decisions, to take action, or to accept risks, hence nurses conceive Avoidance as their primary behavioral style within health care organizations of Crete.

Furthermore, Oppositional culture describes organizations in which confrontation prevails and negativism is rewarded. Oppositional Cultures encourage people to be cynical, argumentative and always find fault. Members are rewarded (usually by peer recognition) to oppose any new ideas or initiatives and to be critical, while refusing to accept criticism [24]. While some oppositional behavior might be desirable in an organization, especially in safety procedures, the amount of such behavior that is ideal is relatively small [24]. Nurses working in health care organizations in Crete face a lack of resources in an organizational model characterized by very little horizontal coordination and very little standardization of procedures, causing ineffective communication, confusing tasks and very often conflicts in the work environment [37]. Conflict is found in all aspects of society and nursing is not immune. However, conflict within the nursing profession has traditionally generated negative feelings and many nurses use avoidance as a coping mechanism [38]. The above, combined with the lack of meritocracy and motivation [39,40], may be decisive factors in the existence of such organizational behaviors.

Furthermore, the most impressive finding of the current study is that nurses overall, but mainly in the tertiary health care organization of Crete, present the lowest scores regarding Constructive cultural norms. The absence of constructive cultural norms shows that nurses working at the University Hospital do not treat each other with dignity and respect, colleagues do not value or support others’ ideas or resolve conflict in a constructive manner, and discourage others from growing and developing. Furthermore, it reveals the lack of teambuilding and participative management [24].

For a profession focus on caring [41], the results show an odd and contradictory frame for nurses working in the public health sector in Crete, in particular those working in the University Hospital. The leading factors in such organizational behaviors are detailed above.

Implications for nursing practice

The current analysis of organizational culture styles among nurses in Crete could potentially facilitate our understanding of those behavioral norms which have a direct impact on medical errors, staffing problems, excessive staff turnover and professional withdrawal. This is imperative, as these events are often directly related to low performance and low quality health care services, underscoring the importance of organizational culture as a key performance determinant in health care services.

Further research (quantitative and qualitative research) should be carried out on organizational culture and the factors that inhibit or facilitate sub groups and health organizations in general in Crete. With the understanding that nurses are the nucleus of a health care organization, it is important for leadership to examine sub-cultures separately but also as a whole, including doctors and other health care professionals, prior to implementation of administrative decisions in health organizations in Crete. Educational programs for health professionals in general and consequently for nurses, concerning the value of constructive culture and the deeper notion of how organizational culture operates and why organizational change could benefit the quality of health care services along with work satisfaction should be a priority. Furthermore, this study underlines the imperative need for organizational changes to reduce the rigid bureaucracy in public health sector organizations and in the overall management of the Greek National Health System. Systems, processes and practices which promote a constructive culture can be instituted at the individual/job level, the manager/unit level and the organizational level, enabling team working and minimizing administrative approaches that fail to infuse a common pattern of values among employees.

Limitations of the study

In the current study the sample was relatively small. The results may not be strictly generalizable to the population of nurses. Additionally, the results are derived from quantitative data and should be complemented by qualitative data. Observations and interviews could provide further evidence regarding the nature of culture among nurses working in the public sector. Finally, particular traits that characterize the Greek National Health Care System, as well as the constantly changing environment in health care services, may not allow generalization to the Health systems of other nations [40].

Conclusions

The recognition of organizational cultures allows the detection and deepening of knowledge, either direct or indirectly, in the planning, execution, control and evaluation of nursing activities. Gaining a more in-depth understanding of nurses’ organizational culture may create the potential to maximize service, quality and outcomes for both health care providers and health customers.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

? “All OCI terminology, style names and descriptions; from Organizational Culture Inventory TM by R.A. Cooke and J.C. Lafferty, Human Synergistics International. Copyright 2015 by Human Synergistics. Adapted by permission.”

8769

References

- Ravasi D, Schultz M (2006) Responding to organizational identity threats: Exploring the role of organizational culture. AcadManag J 49: 433–458.

- Cooke RA, Rousseau DM (1998) Behavioural Norms and Expectations: A quantitative approach to the assessment of organizational culture. Group Organ Stud 13: 245-273.

- Jacobs E, Roodt G (2008) Organizational culture of hospitals to predict turnover intentions of professional nurses. Health SA Gesondheid. J InterdisciplHealth Sci 13: 63-78.

- Scott T, Mannion R, Davies H, Marshall M (2003) The quantitative measurement of organizational culture in health care: a review of the available instruments.Health Serv Res 38: 923-945.

- Brian TG, Stanley G, Armenakis AA, Shook CL (2009) Organizational culture and effectiveness: A study of values, attitudes, and organizational outcomes. J Bus Res 62:673-679.

- Davies HT, Mannion R, Jacobs R, Powell AE, Marshall MN (2007) Exploring the relationship between senior management team culture and hospital performance.Med Care Res Rev 64: 46-65.

- Freund A, Drach-Zahavy A (2007) Organizational (role structuring) and personal (organizational commitment and job involvement) factors: Do they predict interprofessional team effectiveness.J Interprof Care 21:319-334.

- Boan D, Funderburk F (2003) Healthcare Quality Improvement and Organizational Culture. Delmarva Foundation, Easton.

- Singer SJ, Falwell A, Gaba DM, Meterko M, Rosen A, et al. (2009) Identifying organizational cultures that promote patient safety.Health Care Manage Rev 34: 300-311.

- Fisher C, Alford R (2000) Consulting on culture. Consulting Psychology: Research & Practice 52: 206-207.

- Pelletier KR (2005) A review and analysis of the clinical and cost-effectiveness studies of comprehensive health promotion and disease management programs at the worksite: Update VI 2000-2004. J Occup Environ Med 47:1051-1058.

- Sanders EJ, Cooke RA (2005) Financial Returns for Organizational Culture Improvement: Translating “Soft Changes” into “Hard” Dollars. ASTD Expo Orlando, Florida, United States.

- Gifford BD, Zammuto RF, Goodman EA (2002) The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses' quality of work life.J HealthcManag 47: 13-25.

- Draper DA, Felland LE, Liebhaber A, Melichar L (2008) The role of nurses in hospital quality improvement.Res Brief : 1-8.

- Shortell SM, Levin DZ, O’Brien JL, Hughes EFX (1995) Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement/total quality management: concept versus implementation. Health Serv Res 30: 377-401.

- Marcoulides GA, Heck RH (1993) Organizational Culture and Performance: Proposing and Testing a Model. Organ. Sci4:209-225.

- Bellou V (2008) Identifying organizational culture and subcultures within Greek public hospitals. J Health Organ Manag22:496-509.

- Lok P, Westwood R, Crawford J (2005) Perceptions of Organisational Subculture and their Significance for Organisational Commitment. ApplPsycholInt Rev 54:490-514.

- Malliarou M, Sarafis P, Moustaka E, KouvelaTh, ConstantinidisThTC (2010) Greek Registered Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Relation to Work-Related Stress. A Study on Army and Civilian Rns. Glob J Health Sci 2: 44-59.

- Cooke R, Lafferty J (1987) Organizational Culture Inventory® (OCI®). Human Synergistics. Plymouth, Chicago, Illinois, United States.

- Cooke RA (1989) Organizational Culture Inventory® Leader’s Guide. Human Synergistics. Plymouth, Chicago, Illinois, United States.

- Cooke RA, Szumal L (1993) Measuring normative beliefs and shared behavioral expectations in organizations: The reliability and validity of the Organizational Culture Inventory®. Psychol Rep 72:1299-1330.

- Cooke R, Szumal J (2000) Using the Organizational Culture Inventory to understand the operating cultures of organizations. In Ashkanasy NM, Wilderom CPM, Peterson MF(eds.) Handbook of organizational culture and climate, second edition, Sage publications, London, United Kingdom.

- Human Synergistics International (2012) Organizational Culture Inventory Interpretation & Development Guide. Human Synergistics, Boston, United States.

- Xenikou A, Furnham A (1996) A correlational and factor analytic study of four questionnaire measures of organizational culture. Hum Relat49:349-371.

- Rovithis M (2005) Measurement of organizational culture, role conflict and role ambiguity of personnel of the health centers in the island of Crete. Master's thesis. University of Crete, Greece.

- Callen JL, Braithwaite J, Westbrooks JI (2009) The Importance of Medical and Nursing Sub-cultures in the Implementation of Clinical Information Systems. Methods Inf Med 48:196–202.

- Moustafa MS, Gaber MA (2015) Relationship between Organizational Culture, Occupational Stress and Locus of Control among Staff Nurses at Zagazig University Hospitals in Egypt. Int J Health Sci Res 5: 206-218.

- Wooten LP, Crane P (2003) Nurses as implementers of organizational culture.Nurs Econ 21: 275-279, 259.

- Abd-El Rahman R (2004) The Relationship between Health Care Organizational Culture and Nurses' Commitment to the Work. Master Degree, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, El-Gaish Road, Egypt.

- Seago JA (2000) Registered nurses, unlicensed assistive personnel, and organizational culture in hospitals.J NursAdm 30: 278-286.

- Adamakidou T, Kalokerinou A (2008) The organizational frame of the Greek Primary Health Care System. Hellenic J Nurs 47:320-333.

- Bellou V (2010) Organizational culture as a predictor of job satisfaction: The role of gender and age. Career DevInt15: 4-19.

- Balhazard PA, Cooke RA, Potter RE (2006) Dysfunctional culture, dysfunctional organization: Capturing the behavioral norms that form organizational culture and drive performance. J Manage Psychol21:709-732.

- Lentza V, Montgomery AJ, Georganta K, Panagopoulou E (2014) Constructing the health care system in Greece: responsibility and powerlessness.Br J Health Psychol 19: 219-230.

- Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K, Sloane DM, Busse R, et al. (2012) Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States.BMJ 344: e1717.

- Minogiannis P (2012) Tomorrow’s public hospital in Greece: Managing health care in the post crisis era. Soc Cohesion Dev 1:69-80.

- Mahon M, Nicotera A (2011) Nursing and Conflict Communication: Avoidance as Preferred Strategy. NursAdmin Quart 35: 152-163.

- Theodorakioglou Y, Tsiotras GG (2000) The need for the introduction of quality management into Greek health care. J Total Qual Manage 11:1153-1165

- Tountas Y, Karnaki P, Pavi E (2002) Reforming the reform: the Greek National Health System in transition.Health Policy 62: 15-29.

- Watson J (2008) Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring (eds). Caring in nursing classics: An essential resource 243-264.