Case Report - (2022) Volume 13, Issue 5

Pediatric neuromyelitis optica and it management in rural practice in north Togo: About a 13-year-old young girl and review of literature

Léhleng Agba1*,

Nyinèvi Anayo2,

Lihanimpo Djalogue3,

Massaga Dagbe4,

Kokou Mensah Guinhouya2,

Vinyo Kumako1,

Damelan Kombate5,

Kossivi Apetse2,

Abide Talabewi2,

Komi Assogba5,

Mofou Belo2 and

Ayelola Balogou6

1Department of Neurology, University Hospital Center of Kara, Kara, Togo

2Department of Neurology, University Hospital Center of Lomé, Lomé, Togo

3Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Center of Kara, Kara, Togo

4Department of Radiology, University Hospital Center of Kara, Kara, Togo

5Department of Neurology, Regional Hospital Center of Kara, Kara, Togo

6Department of Neurology, University Hospital Center of Campus, Lomé, Togo

*Correspondence:

Léhleng Agba, Department of Neurology, University Hospital Center of Kara,

PoBox 618 Kara,

Togo,

Email:

Received: 07-May-2022, Manuscript No. ipjnn-22-12777;

Editor assigned: 09-May-2022, Pre QC No. P-12777;

Reviewed: 19-May-2022, QC No. Q-12777;

Revised: 25-May-2022, Manuscript No. R-12777;

Published:

31-May-2022

Abstract

Considered for a long time as a particular form of multiple sclerosis

(MS), Devic's disease generally occurs in young women between

20 and 40 years old. This neuro-immunological disease can affect

children and adolescents. It was the case of a 13-year-old student

who came to the clinic with a walking disorder of insidious onset

and ascending progression. Guillain-Barré syndrome was the first

diagnosis retained but when visual troubles occurred, the medullary

MRI and the search for anti Aquaporine-4 (AQP-4) antibodies where

done. The medullary MRI showed a hypersignal in T2 weighted

extended on 6 vertebrae at the cervical level. The anti-AQP-4

antibody was positive. Devic's disease was then recognized in this

young girl who was given intravenous (IV) corticosteroid. The lack

of the therapeutic arsenal in our region did not allow the patient to

receive plasma exchange and IV immunoglobulin as recommended

by the guidelines. However, with corticosteroid therapy at 30

mg/kg/day for 5 days, the neurological disorders stabilized. With

Azathioprine as preventive treatment and physiotherapy, the

patient improved after 3 months, without complete recovery.

Keywords

Devic's neuromyelitis optica; Childhood; Togo; Sub-

Saharan Africa

Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is an

uncommon inflammatory disease of the central nervous

system, manifesting clinically as optic neuritis (ON),

myelitis, and certain brain and brainstem syndromes [1].

For a longtime, Devic's disease was considered a special

form of multiple sclerosis (MS) and treated as such [2].

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) usually occurs in young

women between the ages of 20 and 40 [3]. However, it can

occur in children and teenagers. The recent discovery of

anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) antibodies has led to advances in

the early diagnosis of this disease regardless of the patient's

age. We report the case of a 13-year-old female student who

was seen in a neurology department. Through this case we

will review the literature on the diagnostic and therapeutic

particularities of pediatric forms of NMO.

Case Description

A 13-years old student girl presented to neurology

department of CHU-Kara for a walking disorder started

insidiously and worsened over about 3 weeks. Symptoms

started with bilateral and symmetrical sensory and motor

disorders of the lower limbs followed by an upward

progression from toes to roots of lower limbs within a week.

This presentation suggested an acute polyradiculoneuritis

and a lumbar puncture was performed. The latter revealed

an albuminocytological dissociation on examination of

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). She was treated in internal

medicine with intravenous (IV) corticosteroids for 3 days

and was then referred for physiotherapy. The symptoms

worsened within 2 weeks, marked by an increase in sensory

disorders of the trunk where they were belt-like. These new

symptoms were associated with a decrease in visual acuity,

which led to a referral to neurology. Her personal and

family medical history is unremarkable. On examination,

she was in good general condition and weighed 28 kg for a

height of 1.35 m. She was in a good state of consciousness.

She had no other upper functional disorders. There was a

symmetrical paraparesis that predominated in the distal

parts of the limbs. The muscle strength score was 0/5 for

ankle flexion-extension, 3/5 for knee flexion-extension

and 4/5 for hip flexion. There was no amyotrophy or fasciculation. Deep tendon reflexes of the lower limbs were

sharp with ankle tremor more marked on the right than

on the left. The plantar reflexes test showed Babinski sign

on both sides. There was no motor trouble in upper limbs.

Sensory examination showed superficial and deep sensory

involvement in the lower limbs extending up to the trunk

with a clear sensory level at D6 and a band of hypoesthesia

from D6 to D4. On examination of the cranial nerves,

there was a decrease in visual acuity; the other cranial

nerves were unaffected. She had urinary incontinence.

There was no saddle hypesthesia or anesthesia on perineal

touch. Cardiopulmonary examination showed regular

heart sounds and a eupneic breathing. Spine examination

was normal. The association of the spinal cord syndrome

and the decrease in visual acuity led to the suggestion of

neuromyelitis optica, from which an ophthalmological

consultation was requested. The latter confirmed the

decrease in visual acuity without any pathological sign

on ophthalmoscopy and on a slit lamp examination. The

diagnosis of retrobulbar neuritis was made following this

ophthalmological consultation. The blood cell count

revealed a biological inflammatory syndrome with a

sedimentation rate of 50 mm and a C-Reactive Protein

(CRP) of 36 mg/l. Renal and hepatic functions were

normal. Human immunodeficiency (HIV) serology was

negative. CSF examination showed hyperproteinorrachia

at 1.7g/l with normal glucorarrachia and chlorurrachia.

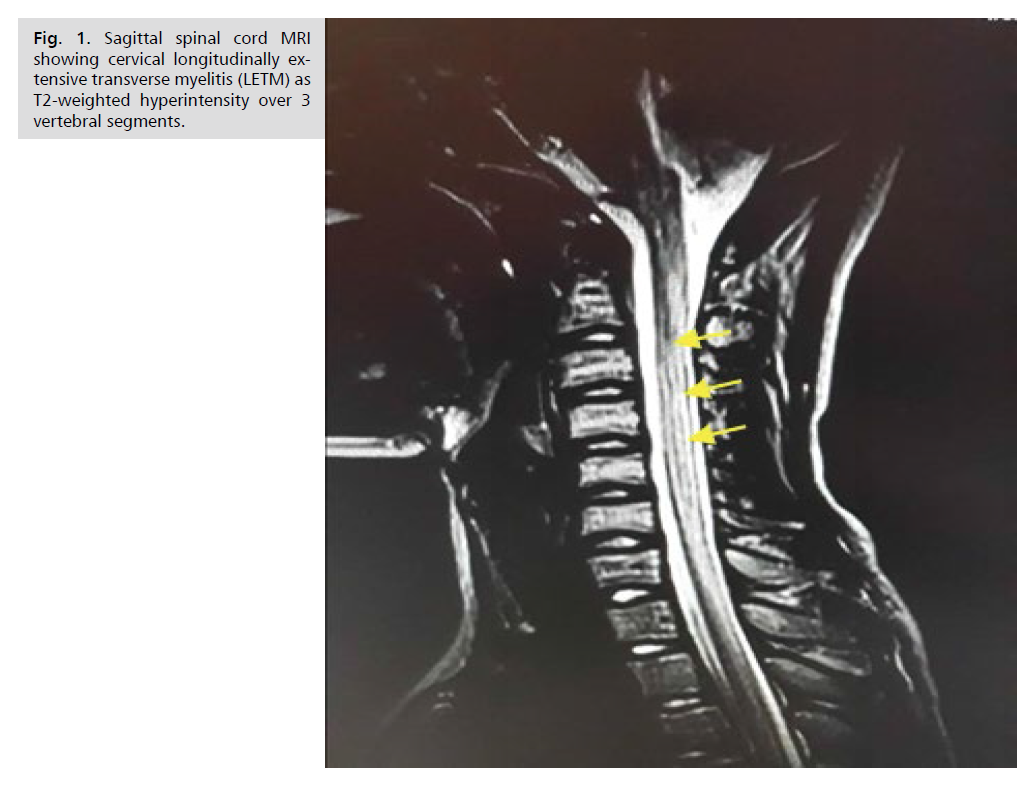

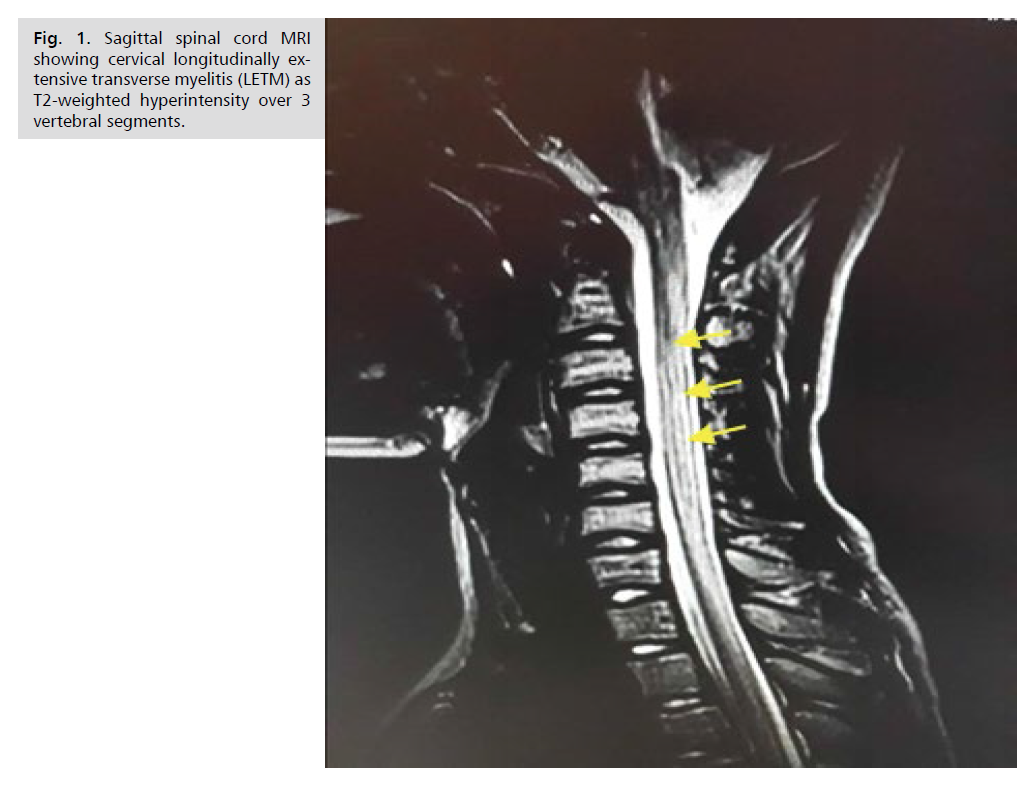

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinal cord

showed extensive hypersignal over 6 vertebral bodies in the cervical region on the T2 sequence (Fig. 1). Brain

MRI was normal. AQP-4 was found to be positive and

anti-myelin olygodendrocyte glycoprotein (anti MOG)

negative. The diagnosis of Devic's neuromyelitis optica was

made, and the patient was given IV corticosteroid at 840

mg of methylprednisolone in the day for 5 days associated.

This corticotherapy was combined with adjuvant treatment

with potassium, calcium, omeprazole and antibiotic

therapy to prevent a urinary tract infection. Physiotherapy

to support the drug treatment was instituted. The patient

has well improved clinically with a recovery of muscle

strength in the lower limbs allowing walking with a walker.

Azathioprine 25 mg orally every 12 hours was given in

addition to the corticosteroid therapy per os and the

patient was discharged from hospital on day-8. Reviewed

one month later, the patient could walk without a cane but

was discreetly ataxic with an overall muscle strength of 4/5

in the lower limbs. The ophthalmology checkup reported a

clear improvement in vision.

Figure 1: Sagittal spinal cord MRI showing cervical longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) as T2-weighted hyperintensity over 3 vertebral segments.

Discussion

We reported Devic's disease in a 13-year-old female

patient who was initially followed for polyradiculoneuritis.

The particularity of our observation is the young age of the

patient. The median age of onset of this disease is 30 to 40

years, but pediatric or late onset, after 80 years, has been

reported [4]. NMO or Devic's disease is an autoimmune

disorder of the central nervous system (CNS), traditionally

restricted to the optic nerve and spinal cord. Like other demyelinating diseases of the CNS, the sex distribution

was strongly skewed toward female, with a female to

male ratio of 6.5:1 [4]. The patient we reported is female,

thus conforming to this female predominance. Myelitis

in NMO is classically presented as a longitudinally

extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) responsible for a

para/tetraplegia associated with a more or less symmetric

bilateral sensory deficit. This spinal cord syndrome is

associated with a sensory level and sphincter disorders [5].

All these characteristics of spinal cord injury were found in

our patient. However, the delay in diagnosis is related to

the absence of ophthalmological signs at the beginning of

the disease. This is supported by the authors who defined

Devic's disease as an association between myelitis and ON

[6]. It is also this association of myelopathy and visual

abnormalities that was reported in the Lancet in 1870

by Albutt [7]. Even if our patient did not present them,

it should be remembered that other clinical signs within

the framework of this disease exist and are well reported.

These include the area postrema syndrome, sleep disorders,

eating and thermoregulation disorders [6]. The diagnosis

of our patient was only evoked when visual disorders

appeared. The occurrence of this new symptom justified

the performance of MRI of the brain and spinal cord

associated with the search for antibodies. Indeed, the spinal

cord MRI confirmed extensive transverse myelitis, which is the most characteristic lesion of NMO [8]. The extensive

longitudinal character defining myelitis in NMO is a

radiological definition characterized by hyperintensity on

T2-weighted sequences that extends over more than three

contiguous spinal segments [6]. These abnormalities in

the spinal cord MRI have been reported to be, in general,

more frequently present in the cervical and the upper

thoracic spinal cord segments than the lower thoracic and

lumbar regions [9]. In our patient, the hyperintensity on

T2-weighted sequences spanned 6 spinal segments and

was located at the cervical level according to the literature

review. Although suggestive, MRI is not pathognomonic

[10], requiring other tests, in particular the search for

specific AQP-4 and anti-MOG antibodies to reinforce

the diagnosis that was evoked on MRI. Our patient had

a positive test of AQP-4 in her serum. In addition to

the clinical presentation and imaging, we confirmed the

diagnosis of NMO despite her young age. Studies have

reported the disease in young age populations. This is the

case of Cabrera-Gomez who reported in Cuba that the

onset of NMO before the age of 20 represented 3.4% of

all NMO cases [11]. More recently in 2020, Tenenbaum

et al. reported that the prevalence of NMOSD in children

represented 3-5% of all NMOSD cases [12]. Since the

discovery of anti AQP-4 antibodies and the numerous

publications reported in the last decades, NMO is now part of a group of pathologies called NMOSD and the

diagnostic criteria are continuously being modified, no

longer being limited to imaging or clinical or serological

criteria (Tab. 1) [13]. Untreated appropriately, NMO has

a rapidly deteriorating course leading to blindness and/

or major motor disability in half of the patients after an

average of five years [14]. Even when treated, the disease

can relapse, with an annual rate higher than in MS [8] of

which it was long considered a clinical form. Mortality in

NMO is high and most often occurs as a result of respiratory

distress related to bulbar extension of the cervical spinal

cord injury. As our patient's location on imaging was

cervical, appropriate treatment was undoubtedly decisive in

preventing bulbar extension in our patient. Currently there

is still no standard treatment protocol for NMO. However,

there are two main aspects to this treatment, namely the

management of relapse episodes and the prevention of

relapses [6]. In general, the management of acute episodes

is based on high dose intravenous corticosteroid therapy

with methylprednisolone at 1g/day for three to five days

followed by prolonged oral corticosteroid therapy [6]. The

particularity of this corticosteroid therapy in children is

the administration and adjustment of the dose according

to weight. It is 30 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone

[15]. This dosage guided our choice of 840 mg per day

of intravenous methylprednisolone in our patient whose

weight was 28 kg. According to the literature review, other

treatments can be used in the acute phase. These are plasma exchange (5-7 cycles) [16] and the use of immunoglobulin.

Several molecules are proposed for relapse prevention

or background treatment of NMO. These include

azathioprine, rituximab, mycophenolate mofetil,

methotrexate, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone

[15,16]. Our patient received azathioprine 25 mg po every

12 hours with a good outcome.

| S. No |

Revised NMOSD Diagnostic Criteria |

| A |

NMOSD with AQP 4-IgG |

1. At least 1 core clinical characteristic |

| 2. Positive AQP4-IgG testing using best available method |

| 3. Exclusion of alternative diagnoses |

| B |

NMOSD without AQP4-IgG

or with unknown AQP4-

IgG status |

1. At least 2 Core clinical characteristics occurring as a result of

1 or more clinical attacks and meeting all of the following: |

a. At least 1 clinical characteristic: Must be optic neuritis,

LETM, or area postrema syndrome |

| b. Dissemination in space (2 or more |

c. Fulfillment of additional MRI requirements different core

clinical characteristics) |

2. Negative tests for AQP4-IgG using best available or testing

unavailable |

| 3. Exclusion of alternative diagnoses |

| C |

Core clinical characteristics |

1. Optic neuritis |

| 2. Acute myelitis |

| 3. Area postrema syndrome |

| 4. Acute brain stem syndrome |

5. Symptomatic narcolepsy or acute diencephalic syndrome

with typical diencephalic MRI lesions |

| 6. Symptomatic cerebral syndrome with typical brain lesions |

| D |

Additional MRI

requirements |

|

| i |

Acute optic neuritis |

a) Brain MRI normal or showing nonspecific white matter

lesions and |

b) Optic nerve MRI with T2-hyperintense or T1-weighted

gadolinium-enhancing lesion extending over >1/2 optic nerve

length or involving optic chiasm |

| ii |

Acute myelitis |

Requires intramedullary MRI lesion extending over ≥ 3

contiguous segments (LETM) or ≥ 3 contiguous segments of

spinal cord atrophy in patients with history compatible with

acute myelitis |

| iii |

Area postrema syndrome |

Requires associated dorsal medulla/area postrema lesions |

| iv |

Acute brainstem syndrome |

Requires associated periependymal brainstem lesions |

Abbreviations: AQP4: Aquaporin-4; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; LETM: Longitudinally Extensive

Transverse Myelitis; NMOSD: Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder

Tab. 1. Revised NMOSD diagnostic criteria [13].

Conclusion

NMO, once rare not only in adults but even more so in

children, is becoming a common condition in recent years.

This is most likely related to a better understanding of the

pathophysiology and a definition of the related conditions

grouped as NMOSD. Although treatment is still under

discussion, high dose corticosteroid therapy in the acute

phase with or without plasma exchange or immunoglobulin

not only prevents fatal outcome but also allows recovery

with fewer sequelae. This condition should be evoked most

often in practice in the pediatric population taking into

account the diagnostic criteria even in the absence of AQP-4.

Acknowledgements

We do not have received any fund for the realization

of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Hor JY, Asgari N, Nakashima I, et al. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and its prevalence and incidence worldwide. Front Neurol. 2020;11:501.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Marignier R, Confavreux C. Neuro-optico-myélite aiguë de Devic et les syndromes neurologiques apparentés. La Presse Médicale. 2010;39(3):371-380.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Vincent T. Neuromyélite optique et NMO-IgG. Revue Francophone des Laboratoires. 2008;404:21-23.

Crossref, Indexed at

- Mealy MA, Wingerchuk DM, Greenberg BM, et al. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica in the United States: a multicenter analysis. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(9):1176-1180.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Jacob A, Weinshenker BG. An approach to the diagnosis of acute transverse myelitis. Semin Neurol. 2008;28(1):105-120.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Albutt TC. On the ophthalmoscopic signs of spinal disease. Lancet. 1870;95(2420):76-78.

Crossref

- Wingerchuk DM, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, et al. A secondary progressive clinical course is uncommon in neuromyelitis optica. Neurol. 2007;68(8):603-605.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Kim HJ, Paul F, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. MRI characteristics of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. An international update. Neurol. 2015;84(11):1165-1173.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Tobin WO, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27(3):279-289.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Cabrera-Gomez JA, Kurtzke JF, González-Quevedo A, et al. An epidemiological study of neuromyelitis optica in Cuba. J Neurol. 2009;256(1):35-44.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Tenembaum S, Yeh EA, Guthy-Jackson Foundation International Clinical Consortium (GJCF-ICC). Pediatric NMOSD: A review and position statement on approach to work-up and diagnosis. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:339.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurol. 2015;85(2):177-189.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, et al. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurol. 1999;53(5):1107-1114.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Tenembaum S, Chitnis T, Ness J, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurol. 2007;68(16 suppl 2):S23-S36.

Google Scholar

- Kimbrough DJ, Fujihara K, Jacob A, et al. Treatment of neuromyelitis optica: Review and recommendations. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2012;1(4):180-187.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

- Trebst C, Jarius S, Berthele A, et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica: recommendations of the neuromyelitis optica study group (NEMOS). J Neurol. 2014;261(1):1-16.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at