Roberto Assandri1*, Marta Monari1 and Alessandro Montanelli2

1Clinical investigation Laboratory, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano, Milan, Italy

2Clinical Chemistry Laboratory, Diagnostics Department, Spedali Civili of Brescia, Brescia, Italy.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Roberto Assandri

Clinical investigation Laboratory, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano, Milan, Italy

Tel: +390282244727

E-mail: roberto.assandri@humanitas.it

Received Date: March 04, 2015; Accepted Date: March 16, 2015; Published Date: March 20, 2015

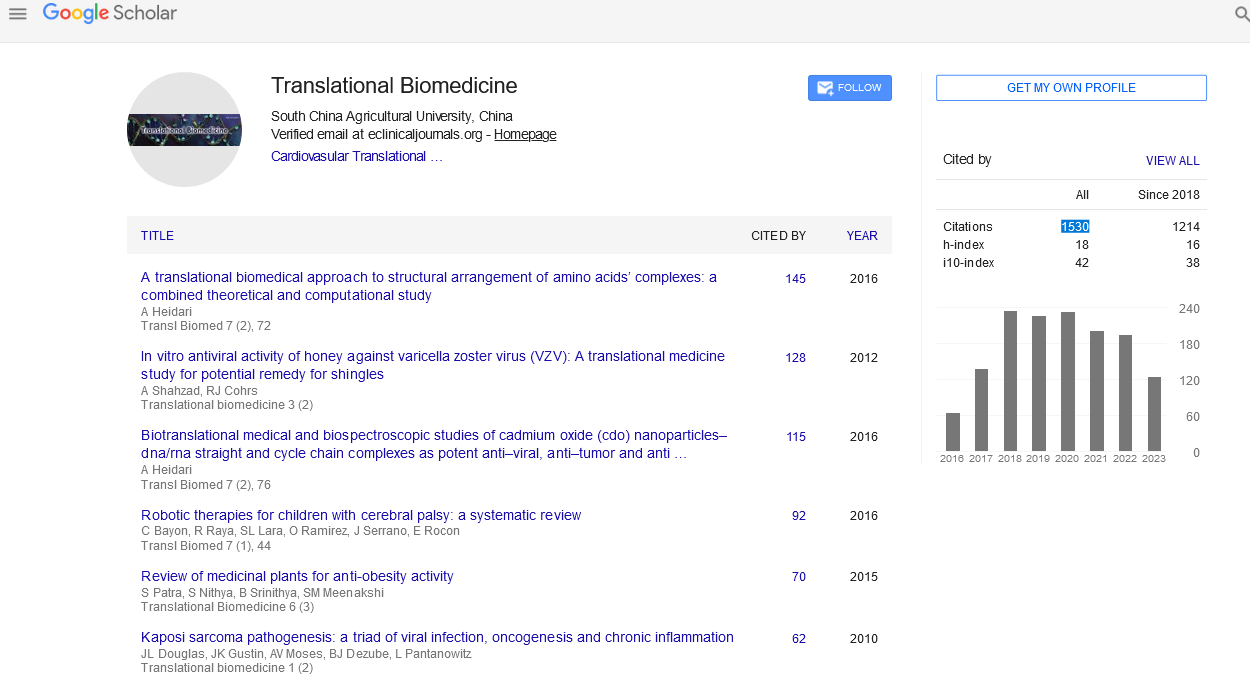

Citation: Assandri R, Monari M, Montanelli A. Pentraxin 3 in Systemic Lupus Erithematosus: Questions to be Resolved. Transl Biomed. 2015, 6:1. DOI: 10.21767/2172-0479.100005

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a autoimmune disorder with unpredictable course that involves polyclonal autoimmunity against multiple autoantigens and presents a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations (fever, skin rashes, arthralgia, inflammation of kidney, lungs, or brain). The pathogenesis of SLE is based on a combinations of genetic variants and environmental factor that promote loss-of-tolerance or tissue inflammation. In fact there is growing evidence to suggest that inflammation and related molecules plays a key role in the pathogenesis of SLE. The pentraxin superfamily (PTXs), divided into long and short PTXs, can induce by and a variety of inflammation-associated stimuli. Alongside the classical short pentraxins C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid P component (SAP), pentraxin 3 ( PTX3) is a prototypic of long pentraxin family, a multifunctional protein characterized by a cyclic multimeric structure and a conserved domain

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a autoimmune disorder with unpredictable course that involves polyclonal autoimmunity against multiple autoantigens and presents a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations (fever, skin rashes, arthralgia, inflammation of kidney, lungs, or brain) [1]. The pathogenesis of SLE is based on a combinations of genetic variants and environmental factors that promote loss-of-tolerance or tissue inflammation [2]. In fact there is growing evidence to suggest that inflammation and related molecules plays a key role in the pathogenesis of SLE.

The pentraxin superfamily (PTXs), divided into long and short PTXs, can induce by a variety of inflammation-associated stimuli [3]. Alongside the classical short pentraxins C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid P component (SAP), pentraxin 3 ( PTX3) is a prototypic of long pentraxin family, a multifunctional protein characterized by a cyclic multimeric structure and a conserved domain [4].

An increasing number of studies identified PTX3 as a key component in the host defence against certain infection such as fungal, bacterial and viral [5,6]. Furthermore, higher circulating PTX3 levels have been observed in cardiovascular diseases [7] and above in some autoimmune disorders, such vasculitis [8], celiac disease (CD) [9] and SLE [10]. Despite of several studies, the literature provides a contradictory picture of PTX3 in SLE patients and, at the moment, have not been yet identified any biochemical markers that allow to accurately monitoring disease activity. Since SLE is characterized by chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction, PTX3 may play a role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Unlike CRP and SAP, PTX3 is produced by resident and innate immunity cells in peripheral tissues, in response to inflammatory signals [11]. However the Literature provides a contradictory picture of PTX3 in SLE pathogenesis and several questions should be resolved. The first issue to be resolved are that the PTX3 are really involved in SLE pathogenesis. In fact it is now known that CRP levels, usually parallel with disease activity in inflammatory states, are often not accompanied by elevated CRP levels [12].

It has been shown that Toll Like Receptor 7 (TLR7) and TLR 9 signalling play a pivotal role in SLE pathogenesis. Very recent study revealed that estrogen receptor α knockout mice have impaired inflammatory responses to TLR 3, TLR4, TLR7 and TLR 9 ligand stimulation in Denditic Cells (DCs) [13]. Also data in mice indicate that TLR4 play a key role in mediating autoimmunity, proinflammatory cytokine production, and other immune activation. TLR4 is one of the best characterized and the first member of the TLR family [14]. TLR4 signaling is implicated in the innate immune responses against a wide-range of microbes, including Gram-negative and -positive bacteria, mycobacteria, spirochetes, yeasts, and some viruses and mammary tumor viruses [14]. TLR4 is implicated in a diverse range of pathological processes associated with autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis, diabetic retinopathy, thrombosis, and inflammatory disorders including arthritis and atherosclerosis [15].

There is evidence of a role of TLR4 in SLE disease pathogenesis, such as the kidney damage, the induction of CD 40 and autoantibodies, the suppression of regulatory T cells, and the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in SLE pathogenesis [16]. In mousemodel sex hormones could directly change TLR4 responsiveness through several mechanisms. Evidences suggested that NFκB is a focal point in the signal transduction cascades that mediate inflammatory cues from antigen receptors on T cells and B cells, and from TLRs on cells of the innate immune system [16]. Besides hypomethylation-driven activation of NFκB-sensitive genes, other oxidation-induced alterations in transcription factor programmes are implicated in SLE [16].

The corresponding PTX3 human gene are located on chromosome 3 band q 25. The proximal promoter share numerous transcription factor binding sequences (such as NF-kB) and [17] it was been demonstrated that NF-kB binding site is essential for PTX3 gene transcriptional response. Also PTX3 is produced in response to a variety nflammatory signals mediated by TLR agonists, IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) [18]. It was elegantly demonstrated that PTX3 was strictly necessary for NF-kB activation in model of intestinal reperfusion injury and underlined a fundamental role of PTX3 in mediating tissue inflammation under sterile conditions [18]. An integrate viewpoint suggested that PTX3 responsiveness lupus is possible and it could speculated that PTX3 may play a role in SLE pathogenesis. After these hypothesis it should be verify that the PTX3 concentration in SLE patients and the possible link between disease activity: the second issue to be resolved. In Hollan study healthy subjects showed a serum PTX3 level as 1.21 ± 0.59 ng/ml [19]. On the other hand Yamasaki reported the mean plasma PTX3 concentration around 2.00 ng/ mL for healthy Japanese people [20]. These different value could be refers to the use of two different matrix (plasma and serum) during the detection of healthy control PTX3 concentration.

Of the 53 healthy controls in Shimada study the mean plasma PTX3 concentration was 2.2 ± 1.1 ng/mL, which was nearly identical to that of the healthy subjects in Yamasaki’s study [20]. Fazzini [21] and Hollan [19] reported serum PTX3 concentrations (not plasma) of 28 SLE patient and three patients with SLE, respectively. The mean serum PTX3 concentration of the 28 SLE patients reported by Fazzini et al. [8], was 0.38 ± 0.50 ng/mL, which was lower than that of 1.00 ± 0.47 ng/mL in their healthy controls. However, 12 of their 28 SLE subjects did not have active disease with SLE activity index (SLEDAI) at zero (SLEDAI=0). On the other hand Kim [22] reported that PTX3 levels were higher in febrile SLE patients but not evaluated SLE patients with active. At the moment it cannot define a single average PTX3 level in healthy subjects and obviously much less in SLE it cannot be define an adequate cut-of point.

These controversial aspect can be resolved by a study with an adequate number of subject in different disease-activity status (SLEDAI score) linked with a careful re-evaluation of the experimental data. An integrated genetics, clinical and basic science viewpoint could be clarify the role of PTX3 in SLE pathogenesis.

5826

References

- Rahman A, Isenberg DA, G. Cambridge, M. J. Leandro, J. Manson, et al. (2008) Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Eng J Med 358: 929-939.

- Migliorini A, Handers HJ (2012) A novel pathogenetic concept-antiviral immunity in lupus nephritis. Nature Reviews Nephrology 8: 183-189.

- Lech M, Römmele C, Kulkarni OP, Heni E S, Adriana M, et al. (2011) Lack of the long pentraxin PTX3 promotes autoimmune lung disease but not glomerulonephritis in murine systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One 6: 20118.

- Deban L, Jaillon S, Garlanda C, Barbara B, Alberto M, et al. (2011) Pentraxins in innate immunity: lessons from PTX3. Cell Tissue Res 343:237-249

- He X, Han B, Liu M (2007) Long pentraxin 3 in pulmonary infection and acute lung injury. Am JPhysiol Lung Cell MolPhysiol292:1039-1049.

- He X, Han B, Bai X, Zhang Yu, Cypel M, et al. (2010) PTX3 as a potential biomarker of acute lung injury: supporting evidence from animal experimentation. Intensive Care Med 36:356-364.

- Hollan I, Bottazzi B, Cuccovillo I, Forre OT, Mikkelsen K, et al. (2010) Increased levels of serum pentraxin 3, a novel cardiovascular biomarker, in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease. Arthritis Care Res 62: 378-385.

- Fazzini F, Peri G, Doni A, Dell’Antonio G, Dal Cin E, et al. (2001)PTX3 in small-vessel vasculitides: an independent indicator of disease activity produced at sites of inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 44:2841-2850.

- Assandri R, Monari M, Colombo A, Montanelli A (2014)Pentraxin 3 serum levels in celiac patients: evidences and perspectives. Recent Pat Food NutrAgric6:82-92.

- Lech M, Römmele C, Kulkarni OP,Heni ES, Adriana M, et al. (2011)Lack of the long pentraxin PTX3 promotes autoimmune lung disease but not glomerulonephritis in murine systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One 6: 20118.

- Bottazzi B, Vouret-Craviari V, Bastone A, Luca DG, Matteucci C, et al. (1997)Multimer formation and ligand recognition by the long pentraxin PTX3. Similarities and differences with the short pentraxins C-reactive protein and serum amyloid P component. J BiolChem272:32817-32823.

- Keenan RT, Swearingen CJ, Yazici Y (2008) Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are poorly correlated with clinical measures of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and osteoarthritis patients. ClinExpRheumatol26:814-819.

- Marshak-Rothstein A (2006) Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol6: 823-835.

- Zarember KA, Godowski PJ (2002) Tissue expression of human Toll-like receptors and differential regulation of Toll-like receptor mRNAs in leukocytes in response to microbes, their products and cytokines. J Immunol168: 554-561.

- Jiang W, Gilkeson G (2014) Sex Differences in monocytes and TLR4 associated immune responses; implications for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). J ImmunotherAppl 1: 1.

- Qin H, Wilson CA, Lee SJ, Zhao X,Benveniste EN (2005) LPS induces CD40 gene expression through the activation of NF-kappaB and STAT-1alpha in macrophages and microglia. Blood 106:3114-3122.

- Souza DG, Vieira AT, Pinho V, Sousa LP, Andrade AA, et al (2005) NF-kB plays a major role during the systemic and local acute inflammatory response following intestinal reperfusion injury. Br J Pharmacol145: 246-54.

- Han B, Mura M, Andrade CF, Okutani D, Lodyga M, et al (2005) TNF-alpha-induced long pentraxin PTX3 expression in human lung epithelial cells via JNK. J Immunol 175: 8303-8311.

- Hollan I, Bottazzi B, Cuccovillo I, Forre OT, Mikkelsen K, et al (2010) Increased levels of serum pentraxin 3, a novel cardiovascular biomarker, in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease. Arthritis Care Res 62:378-385.

- Yamasaki K, Kurimura M, Kasai T, Sagara M, Kodama T, et al. (2009) Determination of physiological plasma pentraxin 3 (PTX3)levels in healthy populations. ClinChem Lab Med 47:471-477.

- Fazzini F, Peri G, Doni A, Dell’Antonio G, Dal Cin E, et al. (2001)PTX3 in small-vessel vasculitides: an independent indicator of disease activity produced at sites of inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 44:2841-2850.

- Kim J, Koh JK, Lee EY, Park JA, Kim HA, et al. (2009) Serum levels of soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (sTREM-1) and pentraxin 3 (PTX3) as markers of infection in febrile patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. ClinExpRheum27:773-778.