Laboratory Markers and Outcome in Patients with Non Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Receiving Early Endoscopic Treatment

Keywords

Inflammatory markers; Upper gastrointestinal; Non variceal gastrointestinal bleeding; Early endoscopy; Outcome

Introduction

Non variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) is an important emergency situation and the need for early risk stratification for rebleeding has been underlined in recent literature. Several risk factors such as advanced age, liver cirrhosis, cardiac failure, the usage of antiplatelet or anticoagulants agents and hemodynamic instability may influence the occurrence of bleeding or predict mortality. There are studies that focus on the peptic ulcer bleeding as the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding [1,2]. The incidence of NVUGIB ranges from 48 to 160 cases per 100,000 adults per year [3]. Clinical predictors of increased risk for mortality are age(>65 years), presence of shock, low initial hemoglobin (Hb) levels, transfusion requirement, elevated Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), Creatinine (Cr) and White Blood Cells (WBC) levels. Moreover, the risk of mortality increases with presence of rebleeding, which is thus another major outcome [4]. Based on recent studies conducted in Europe the mortality rate remains 5% to 14%, in United States of America and Asia and it reduces when patients submitted in early endoscopy (according to Forrest classification) [5]. Mortality rate have started to decrease because of the use of early endoscopy (≤ 24 hours) for diagnosis and treatment, proton pump inhibitors and other preventive strategies [5-7]. Second-look endoscopy is not routinely recommended but it may be useful in selected high-risk patients [8]. Urgent therapeutic endoscopy has become a useful tool for gastroenterologists and may affect patients’ outcome as it contributes to identification of the bleeding source, risk stratification, and additionally applying the proper therapeutic intervention. The time of endoscopy performance it is still in doubt as there is not enough evidence which support that endoscopy performed less than 12 hours of patient admitted to emergency room can reduce the risk of rebleeding or improve survival rate compared to endoscopy later performance [4,7-9]. In UGIB patients the pre-endoscopic Glasgow Blatchford risk score and Rockall score are also useful tools to predict the need for intervention and mortality rate, respectively [9,10]. During the last two decades, several studies have indicated that there is a close correlation between low Hemoglobin (Hb) levels, elevated White Blood Cell (WBC) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and increased risk for rebleeding [11]. However, there are no data regarding procalcitonine (PCT) levels to assess patients for the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding prior to endoscopy.Thus, the aim of the present work was to evaluate the changes in levels of inflammatory (WBC, PCT and CRP) and other laboratory markers in patients with non variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Material and Methods

Study design

This is a prospective study conducted in a general hospital of Athens, Greece.

Participants

Between February 2015 and January 2016, a total of 101 patients, >18 years old presenting to the emergency room with symptoms of UGIB were included to the study. The recurrence of UGIB and inpatients were the exclusion criteria of the study. Moreover, patients referred by another institution after initial treatment were also excluded. Patients with documented Forrest classification 1a, 2a and 2b were considered eligible and included to the study.

Data collection

Date included demographic characteristics, vital signs, comorbidities, laboratory values, and endoscopic treatment (e.g. primary hemostasis).

Blood test variables

Procalcitonin (PCT), White Blood Cells (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP) Hemoglobin (Hb) , Hematocrits (Hct) and Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) levels were analyzed before endoscopy (admission day), and 3, 7 days prior endoscopy.

Scores

Risk scoring systems, such as Glasgow Blatchford risk score and Rockall score were calculated according to clinical and laboratory data, so as patients could receive an early endoscopic treatment.

Follow up

Three and seven days after hospital admission clinical and laboratory findings were recorded.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital. Written informed consent was obtained for the endoscopy from all the patients.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean values ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as frequencies. A repeated measures ANOVA analysis was applied. Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated that sphericity was violated (p<0.75); Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used. Non parametric test (Mann-Whitney U-test) was performed in order to determine whether there is statistical evidence that patients’ laboratory findings means are significantly different in 3-time points. Data analysis was performed by using the statistical package SPSS, ver. 20.

Results

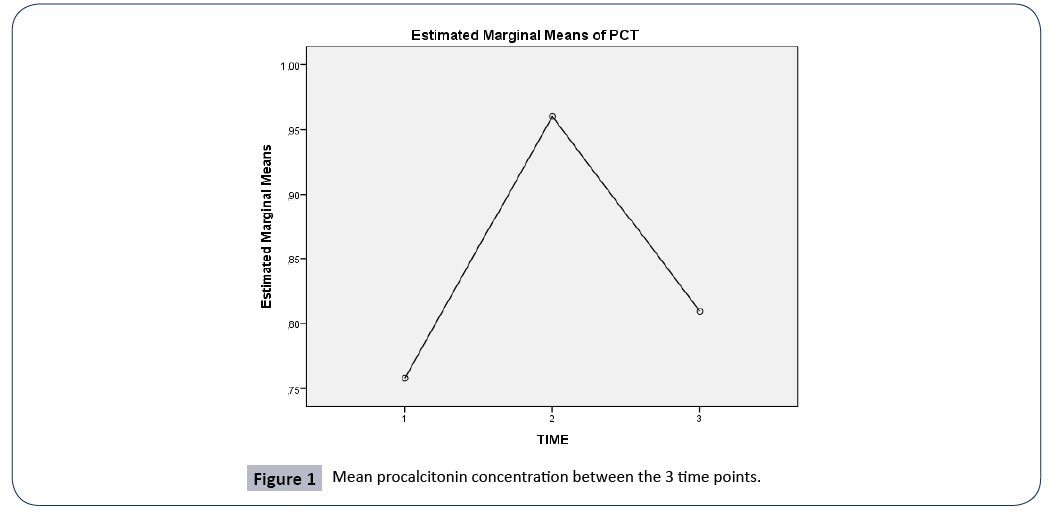

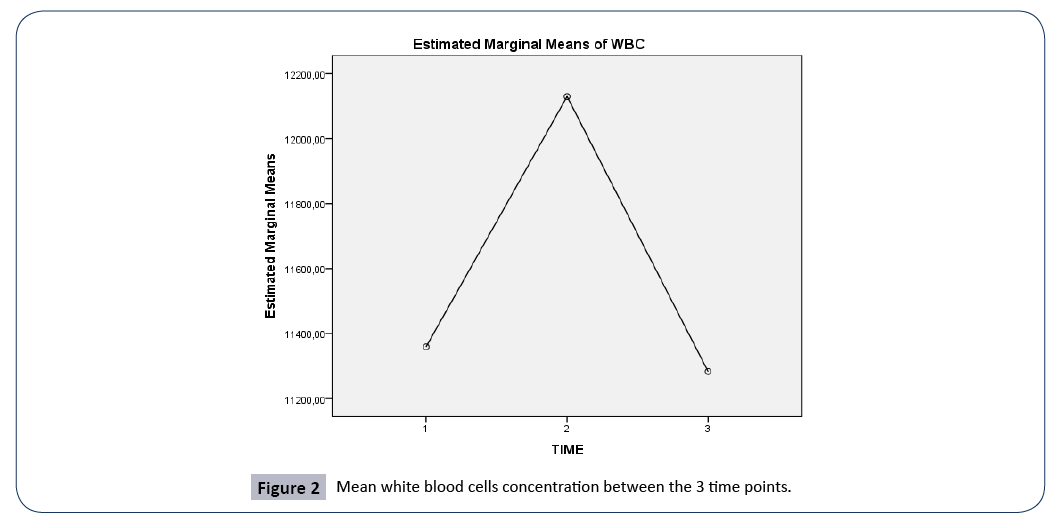

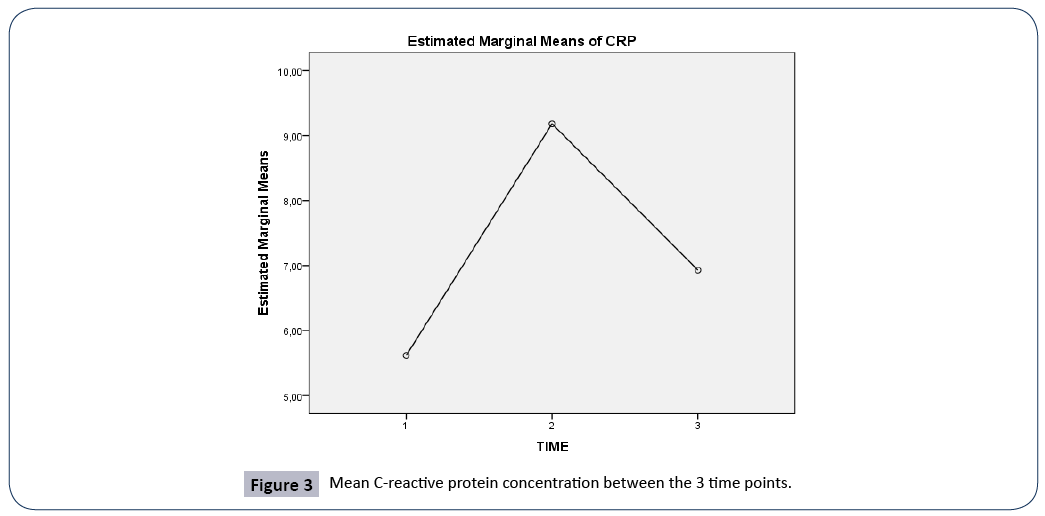

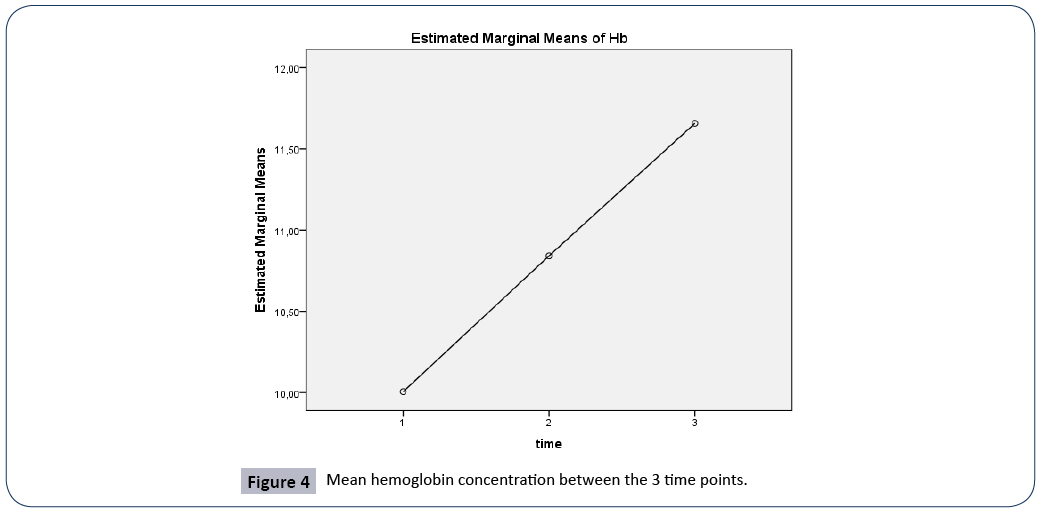

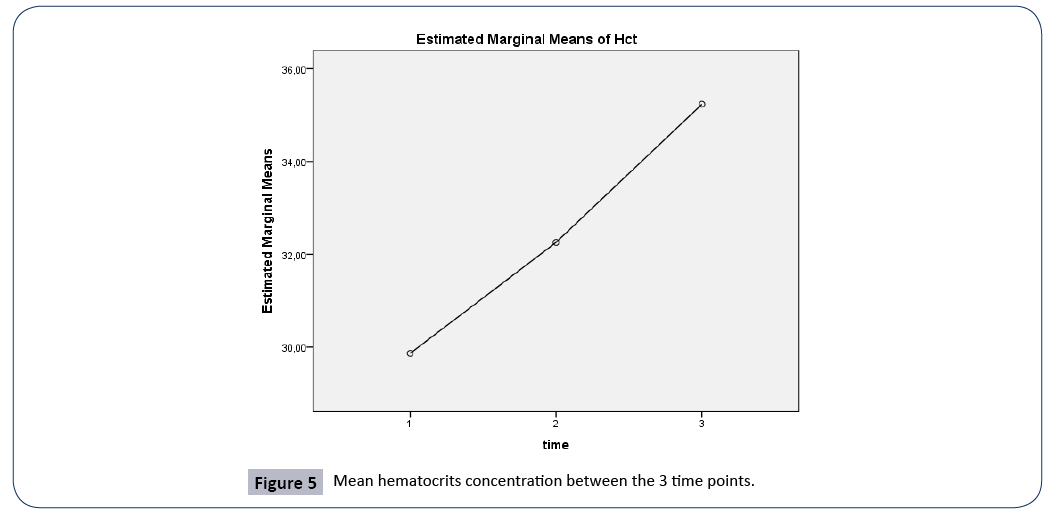

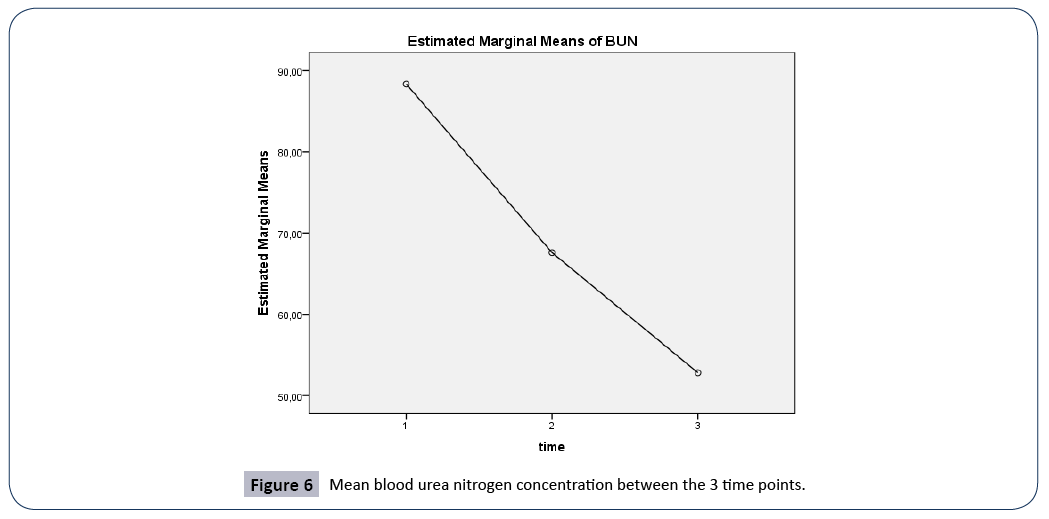

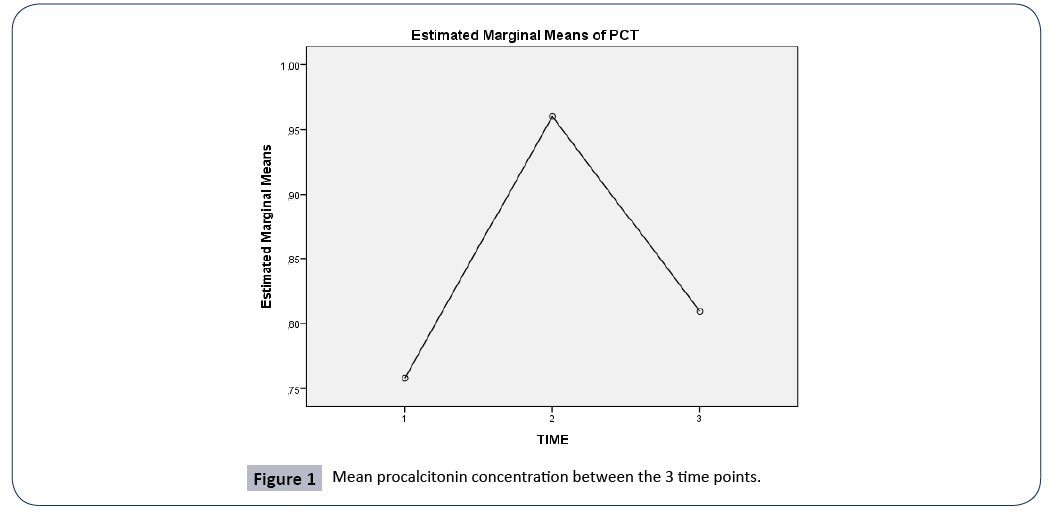

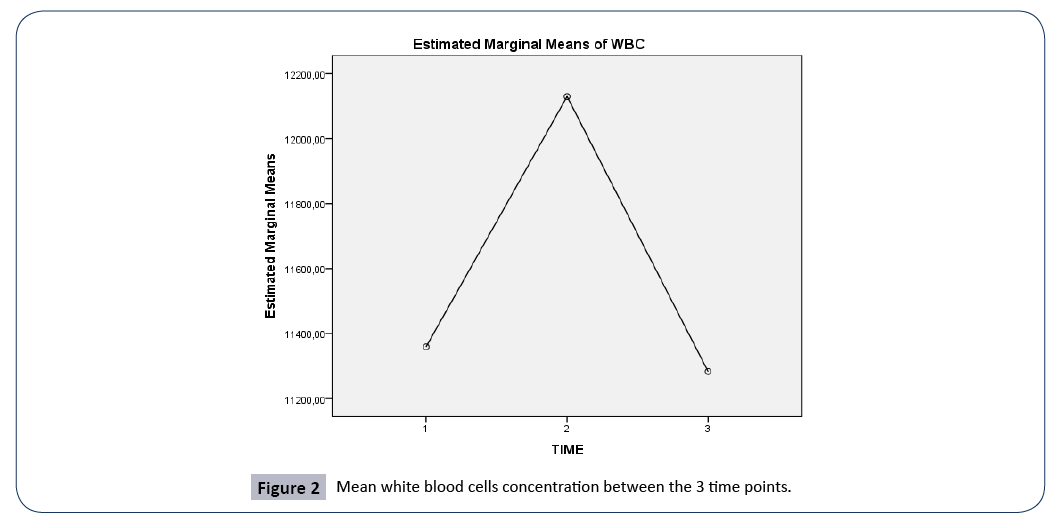

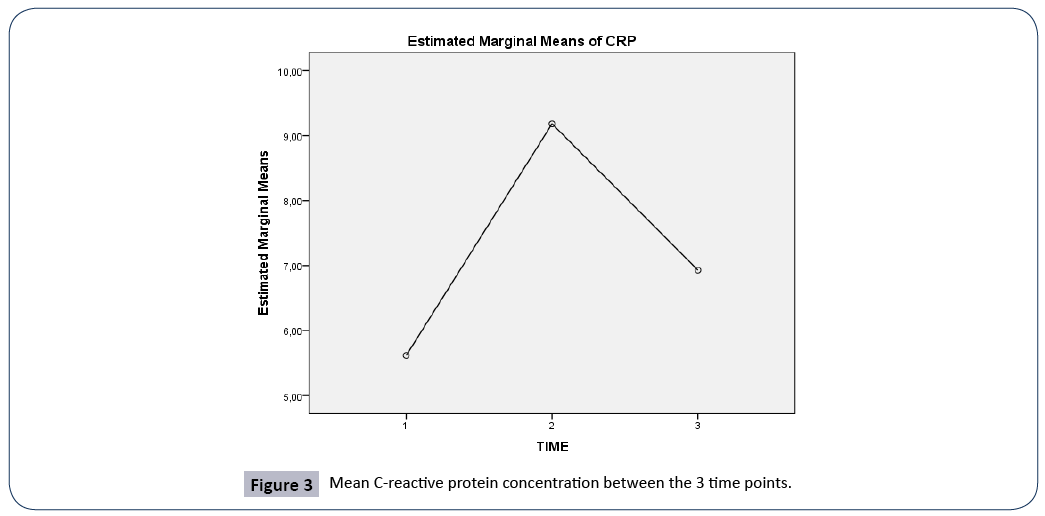

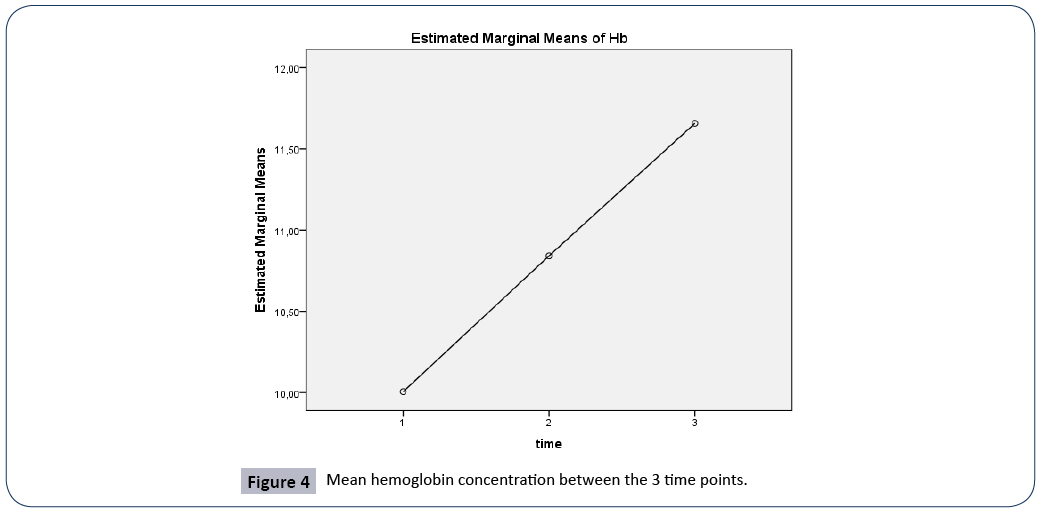

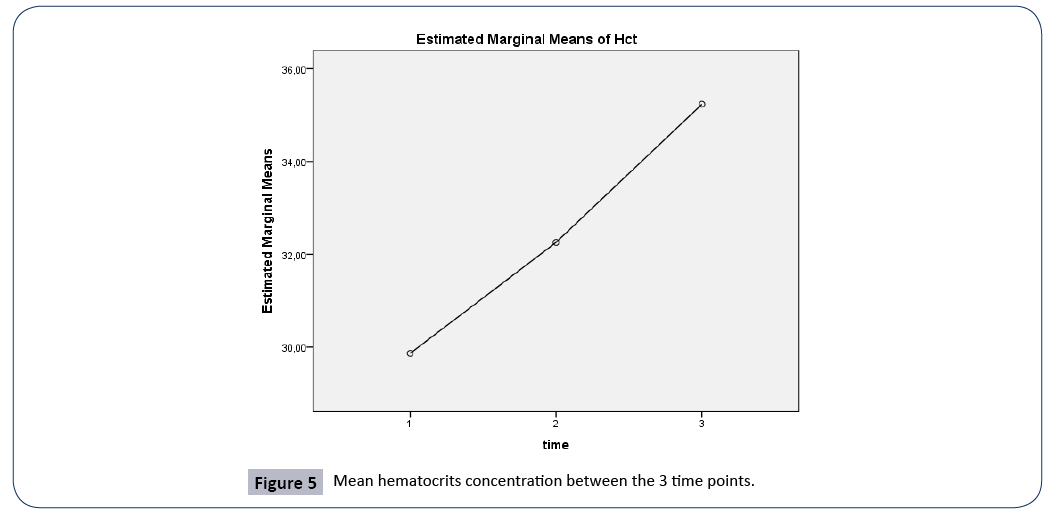

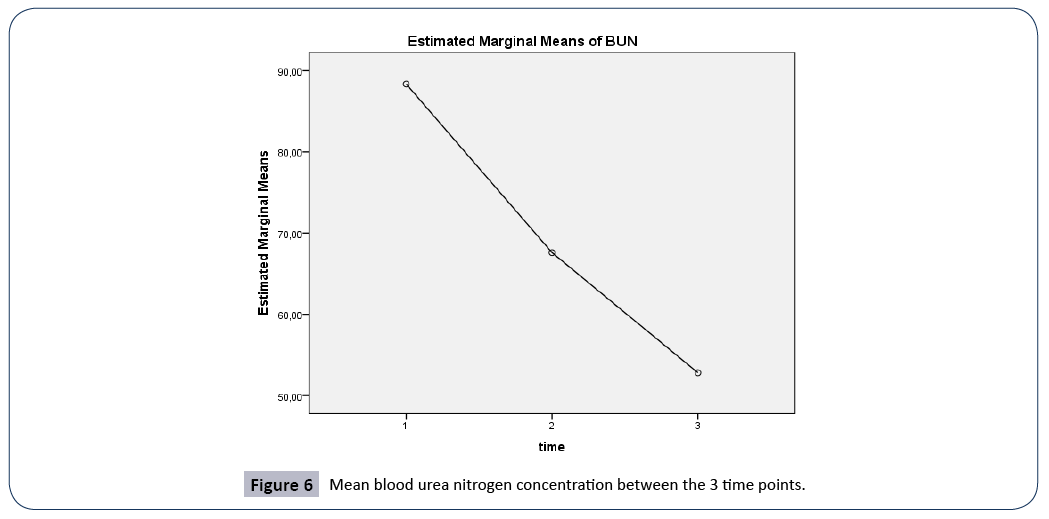

The demographic characteristics and clinical scores of the studied sample are presented in Table 1. A repeated measures ANOVA analysis was applied so as to compare PCT, WBC, CRP, Hb, Hct and BUN levels between 3 time points; during hospital admission, 3 and 7 days later, (Table 2 and Figures 1-6). All comparisons were applied to the total studied sample. The 7-days survival rate was 94.1%.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the studied patients. SD: Standard Deviation.

| |

Mean ± SD |

% (n) |

| Gender |

| Men |

|

67.3 (68) |

| Women |

|

32.7 (33) |

| Age, (years) |

67.7 ± 16.9 |

|

| Scores |

| Rockall’s score |

2.1 ± 0.69 |

|

| Glasgow Blatchtford score |

3.4 ± 0.78 |

|

| Endoscopic treatment |

| Adreanline injection |

|

53.1 (17) |

| Clips |

|

12.5 (4) |

| Adreanline injection+Clips |

|

21.9 (7) |

| Monoethanolamine oleate injection |

|

3.1 (1) |

| Argon plasma coagulation or APC |

|

9.4 (3) |

| None |

|

68.3 (69) |

| Patients’ outcome |

| Alive, (Yes, %) |

|

94.1 (95) |

Table 2 Repeated measures of inflammatory and other laboratory markers between 3 time points. SD: Standard Deviation, PCT: procalcitonin, WBC: White blood cells, CRP: C-reactive protein, Hb: Hemoglobin, Hct: Hematocrits, BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen.

| Variables |

Admission time Mean ± SD |

Day 3 Mean ± SD |

Day 7 Mean ± SD |

p |

| PCT (ng/mL) |

0.7 ± 1.1 |

0.9 ± 1.3 |

0.8 ± 1.0 |

0.389 |

| WBC count (/μL) |

11.358 ± 4.213 |

12.129 ± 3.675 |

11.283 ± 3.229 |

0.215 |

| CRP (mg/dl) |

5.6 ± 5.6 |

9.1 ± 7.3 |

6.9 ± 5.9 |

<0.005 |

| Hb (g/dL) |

10 ± 2.4 |

10.8 ± 1.7 |

11.6 ± 1.9 |

0.906 |

| Hct (%) |

29.8 ± 6.9 |

32.2 ± 5.9 |

35.2 ± 5.8 |

0.486 |

| BUN (mg/dL) |

88.3 ± 58.4 |

67.5 ± 45.7 |

52.8 ± 40.7 |

0.164 |

Figure 1: Mean procalcitonin concentration between the 3 time points.

Figure 2: Mean white blood cells concentration between the 3 time points.

Figure 3: Mean C-reactive protein concentration between the 3 time points.

Figure 4: Mean hemoglobin concentration between the 3 time points.

Figure 5: Mean hematocrits concentration between the 3 time points.

Figure 6: Mean blood urea nitrogen concentration between the 3 time points.

PCT

A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined that mean PCT concentration did not differ statistically significantly between the 3 time points (F (1.999, 199.86)=0.949, p=0.389).

WBC

A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined that mean WBC concentration did not differ statistically significantly between the 3 time points (F(1.898, 189.75)=1.552, p=0.215).

CRP

A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined that mean scores for CRP concentration were statistically significantly different between the 3 time points (F(1.990, 199.04)=11.202, p<0.005). Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction revealed that there was a significant difference in CRP concentration between 3rd and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.0005), and between 1st day of admission and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.001), but no significant differences between 1st and 3rd day of admission, (p=0.234).

Hb

A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined that mean Hb concentration were statistically significantly different between the 3 time points (F(1.577, 157.694)=67.105, p<0.005). Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction revealed that there was a significant difference in Hb concentration between 3rd and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.0005), between 1st day of admission and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.001), and between 1st and 3rd day of admission, (p<0.0005).

Hct

A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined that mean Hct concentration were statistically significantly different between the 3 time points (F(1.941, 194.052)=58.029, p<0.005). Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction revealed that there was a significant difference in Hct concentration between 3rd and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.0005), between 1st day of admission and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.001), and between 1st and 3rd day of admission, (p<0.0005).

BUN

A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction determined that mean BUN concentration were statistically significantly different between the 3 time points (F(1.369, 136.949)=34.543, p<0.005). Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction revealed that there was a significant difference in BUN concentration between 3rd and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.0005), between 1st day of admission and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.001), and between 1st and 3rd day of admission, (p<0.0005).

In Table 3, correlations between laboratory markers and patients’ outcome are presented. It can be concluded that the survival group had statistically significantly lower BUN concentration than non-survived patients at the 2 time points, (Day 3: U=124.5, p=0.021, Day 7: U=108.5, p=0.011).

Table 3 Correlations between laboratory markers and patients’ outcome (survival-non survival). PCT: Procalcitonin, WBC: White Blood Cells, CRP: C-Reactive Protein, Hb: Hemoglobin, Hct: Hematocrits, BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen. *p<0.005.

| Variables |

|

Mann-Whitney U |

p |

| PCT (ng/mL) |

Admission time |

273.000 |

0.863 |

| Day 3 |

267.500 |

0.801 |

| Day 7 |

235.500 |

0.476 |

| WBC count (/μL) |

Admission time |

280.500 |

0.948 |

| Day 3 |

285.000 |

1.000 |

| Day 7 |

170.500 |

0.100 |

| CRP (mg/dl) |

Admission time |

273.500 |

0.869 |

| Day 3 |

205.000 |

0.250 |

| Day 7 |

265.500 |

0.779 |

| Hb (g/dL) |

Admission time |

226.000 |

0.397 |

| Day 3 |

253.000 |

0.646 |

| Day 7 |

196.500 |

0.203 |

| Hct (%) |

Admission time |

220.500 |

0.354 |

| Day 3 |

280.500 |

0.948 |

| Day 7 |

184.000 |

0.147 |

| BUN (mg/dL) |

Admission time |

186.500 |

0.157 |

| Day 3 |

124.500 |

0.021* |

| Day 7 |

108.500 |

0.011* |

Discussion

According to the results of the present study, there was a significant difference in CRP and other laboratory markers (Hb, Hct, BUN) concentration between 3rd and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.0005), and between 1st day of admission and 7th day of hospitalization (p<0.001). Early endoscopic therapy may result in the reduction rate of complications after hospital discharge, reduction of inflammatory and other markers levels and improve patients’ outcome, since endoscopic hemostasis or other therapy is achieved with safety and efficiency. Hoffmann et al. [12] revealed in their study that blood test variables are easy to evaluate and demonstrated that changes in WBC, Hb, CRP, and Cr levels are strongly associated with UGIB. Recent literature underlines the importance of CRP as a prognostic indicator of gastrointestinal bleeding or rebleeding after hospital discharge. Tomizawa et al. [13] studied the early upper gastrointestinal endoscopy significance related to mortality rate resulting from upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. They examined the results of blood examination the day and 3 months prior to endoscopy in 156 patients. CRP levels considered as useful indicators of inflammation along with other markers. The study demonstrated that CRP level was higher in the bleeding group than in the non-bleeding group, with a statistical significance difference. Moreover, Lee et al. [14] in their study tried to explore the role of CRP level in risk prediction of rebleeding in patients with acute NVUGIB. According to their results, the incidence of 30- day rebleeding was 15.9% with these patients having significant higher serum CRP than patients without rebleeding; indicating a possible role of CRP as predictor of rebleeding. In our study, Hb levels were found to be increased at 7 day follow up. A possible explanation for this finding is the fact that during endoscopy an efficient hemostasis is performed through a variety of methods (endoscopic clips, adrenaline injection, argon plasma coagulation) which result in accomplishing elevated levels of Hb and Hct concentration. Blood transfusion is not always helpful and recent literature reveals that the Hb threshold for transfusion of red cells in patients with AGIB is controversial. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends a restrictive red blood cell transfusion strategy that aims maintaining Hb levels between 7.0–9.0 g/dl in order to reduce mortality. Comparisons of blood test variables between patients with or without upper GI bleeding was performed by Tomizawa et al. [15] who included 1,023 patients in their study aiming at identifying the importance of these variables on patients outcome. They revealed that WBC, and BUN were elevated and Hb was reduced in patients with upper GI bleeding. The present study demonstrated that the survival group had statistically significantly lower BUN concentration than non-survived patients at the follow up time. This finding come in accordance with other studies findings conducted the last decade. It is supported that BUN level is a significant predictor of patients outcome [16]. Tomizawa et al. [17] in their retrospective study conclude that patients with BUN ≥ 21 mg/dL might have more severe upper GI bleeding. Additionally, Kumar et al. [18] in their retrospective cohort study aimed at assessing the predictive role of increase BUN in clinical outcome of 357 patients with NUGIB. It was found that patients with increased BUN were significantly more likely to have an increased risk of inpatient death compared with patients with a decreased or unchanged BUN. Moreover, an increase BUN at 24 hours of hospitalization was a significant predictor of composite clinical outcome.One limitation of the present study was that it was based on a small sample size.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the changes in levels of inflammatory and other laboratory markers in patients with non variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding and its reflection to survival rate. Safe and efficient management of non-variceal UGIB is of utmost importance for patients admitted to the hospital. After stabilization of the patient’s condition, endoscopic evaluation remains the most reliable method to identify the origin of acute bleeding. Laboratory test variables may predict patient outcome related to presence and severity of rebleeding or mortality rate in NUGIB.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

24762

References

- van Leerdam ME (2008) Epidemiology of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 22:209-224.

- Lee YJ, Min BR, Kim ES, Park KS, Cho KB, et al. (2016) Predictive factors of mortality within 30 days in patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Korean J Intern Med 31:54-64.

- van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, Geraedts AA, Tijssen JG, et al. (2003) Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol 98:1494-1499.

- Rotondano G (2014) Epidemiology and diagnosis of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 43:643-663.

- Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, Lanas A, Sanders DS, et al. (2015) Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guideline. Endoscopy 1-46.

- Marmo R, Koch M, Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Grossi E, et al. (2014) PNED 1 and PNED 2 Investigators. Predicting mortality in patients with in-hospital nonvariceal upper GI bleeding: a prospective, multicenter database study. Gastrointest Endosc 79:741-749.

- Jairath V, Martel M, Logan RF, Barkun AN (2012) Why do mortality rates for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding differ around the world? A systematic review of cohort studies. Can J Gastroenterol 26:537-543.

- Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, et al. (2010) International Consensus Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Conference Group. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med 152:101-103.

- Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, Lanas A, Sanders DS, et al. (2015) Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guideline. Endoscopy 47:a1-46.

- Holster IL, Kuipers EJ (2012) Management of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: current policies and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol 18 :1202-1207.

- Tammaro L, Buda A, Di Paolo MC, Zullo A, Hassan C, et al. (2014) T-Score Validation Study Group; T-Score Validation Study Group. A simplified clinical risk score predicts the need for early endoscopy in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Liver Dis 46:783-787.

- Hoffmann V, Neubauer H, Heinzler J, Smarczyk A, Hellmich M, et al. (2015) A novel easy-to-use prediction scheme for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Cologne-WATCH (C-WATCH) risk score. Medicine (Baltimore) 94:e1614.

- Tomizawa M, Shinozaki F, Hasegawa R, Togawa A, Shirai Y, et al. (2014) Reduced hemoglobin and increased C-reactive protein are associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 20:1311-1317.

- Lee HH, Park JM, Lee SW, Kang SH, Lim CH, et al. (2015) C-reactive protein as a prognostic indicator for rebleeding in patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Liver Dis 47:378-383.

- Tomizawa M, Shinozaki F, Hasegawa R, Shirai Y, Motoyoshi Y, et al. (2016) Low hemoglobin levels are associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Biomed Rep 5:349-352.

- Al-Naamani K, Alzadjali N, Barkun AN, Fallone CA (2008) Does blood urea nitrogen level predict severity and high-risk endoscopic lesions in patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding? Can J Gastroenterol 22:399-403.

- Tomizawa M, Shinozaki F, Hasegawa R, Shirai Y, Motoyoshi Y, et al. (2015) Patient characteristics with high or low blood urea nitrogen in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 21:7500-7505.

- Kumar NL, Claggett BL, Cohen AJ, Nayor J, Saltzman JR (2017) Association between an increase in blood urea nitrogen at 24 hours and worse outcomes in acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 86:1022-1027.