Keywords

Contraceptive methods, family planning, sex education, nursing students, planned parenthood

Introduction

Epidemiologists generally agree that responsible parents should plan a family with three children in an effort to maintain rather than increase world population. Sadly, in Greece, we are at the top of abortion statistics (by comparison to our population) as against the number of live births, while at the same time our nation’s birth rate is unacceptably low. This concurs with an exacerbation of sexually transmitted diseases which directly influence fertility. [1] Thus, it is essential that appropriate contraception providing the necessary protection from unwanted pregnancy and other effects be practiced. Choice of method should be based on the degree of effectiveness and protection provided. The failure rate of any individual method of contraception depends on many factors, such as its inherent disadvantages, a woman’s lack of determination to use it correctly, her age, a limited period of implementation, i.e. inadequate experience, etc. [2,3]

Statistical studies carried out in the USA from 1982 to 1995 show that the percentage of women using contraception was 56% in 1982 and reached 64% in 1995. From 1982 to 1988, female sterilization, the pill and male condoms were the most widespread forms of contraception. Between 1988 and 1995, the percentage of women on the pill dropped from 31% to 27%, whereas the use of condoms rose from 15% to 20%.

In 1982, approximately 30 million women aged 15 – 44 were using various forms of contraception, and by 1998 this figure had reached 39 million. Between 1988 and 1995, the increase in the use of contraception was chiefly linked to condoms, with 5.1 to 7.9 million users. [4-8] Male condoms are a particularly popular method of contraception, and when used properly are 98% effective in preventing pregnancy. [9] This is an exceptionally high rate, and thus the question to be investigated concerns the situation regarding other methods of contraception in Greece, i.e. apart from condoms and the pill, and especially those which are considered to be less effective. It is a fact that the development and the variety of contraception methods over the past years have resulted in substantial changes in the field of family planning. Changes in the composition of oral contraceptives and the discovery of the female condom are two typical examples of this. [2,3,10] Alongside the choices made by Greeks, and especially young Greeks, in these matters, questions also arise as to our population’s sources of information and the credibility thereof. Furthermore, we need to discover which other factors influence choice of method ? an especially pressing issue because international data shows that young people today display high?risk sexual behavior. [11,12]

Sample and Methods

Sample

The population which made up the substance of this study consisted of 350 students at the Technical University (TEI) of Athens.

The sample comprised students from the School for Health Care Professions (SHCP), registered in the departments of Health Visiting (HVD) (28.6%), Medical Laboratories (MLD) (25.1%), Nursing (ND) (18.5%) and the School of Economic Administration (SEA) (27.8%), representing first? through final year levels of study.

The study was carried out from 01/10/03 to 31/03/04, based on a questionnaire. After they had been introduced to the purpose of the study, each subject completed a questionnaire comprising 25 questions, including 7 concerning their sex lives and 11 regarding sex education. The majority of the sample was positively disposed towards completing the questionnaire.

Methods

During the initial phase of our research, a pilot study was carried out, for the purpose of evaluating how easy the questionnaire was to fill out, as well as the clarity and precision of the data involved [12]. This was followed by an amendment of the questionnaire according to the requirements of the study. The subject matter and wording of all questions was designed to protect the privacy and identity of all participants.

Data analysis

Data collection was carried out by way of a questionnaire, and the data was subsequently subjected to a statistical analysis. Specifically, completion of the questionnaires was followed by codification control and creation of a data file for the study. Next, the variables contained in the sample were recorded. The distribution of percentage frequencies of the multiple values for each variable allowed for an initial overview of the sample.

Subsequently, we looked for a correlation among selected variables (crosstabs), for the purpose of a more thorough investigation and in order to achieve a more succinct outline. Contingency tables and Pearson’s x² ? test were used to test the hypothesis for correlation between two nominal random variables. Where Pearson’s test could not be applied (some cells have zero observed frequencies, or expected frequency for some cells is less than five) Fisher’s exact test was used instead. All tests are at a = 0.05 level of significance unless otherwise stated.

Results

The mean age of our sample was 21.1 ± 2.45, and it consisted chiefly of women (84.9%). The overwhelming majority were Greek citizens (94%), and 96% stated their religion to be “Christian Orthodox”. Distribution of the sample in terms of geographical origin was as follows:

a) 44% from Athens or Piraeus

b) 54% from elsewhere in Greece

c) 7% foreigners

Our data shows that 90% had had sex at some point in their lives, and that their first sexual encounter took place at the age of 18.2 ± 1.7 years.

80.7% of the sample stated that they were familiar with the purpose of Planned Parenthood, or family planning, and approximately 85% believed that it concerns both men and women. 91.1% stated that sex education should be provided during adolescence, and according to 96%, it is a good idea for it to be offered within the framework of an educational program. The persons most appropriate to provide sex education were thought to be doctors by 65.6%, followed by health visitors, at 19.6%, while only 2 ? 5% chose one of the other categories of health care professionals (midwives, nurses, social workers, psychologists, or others). Those who did not have a sex life had never seen a health professional, as opposed to the rest: here 35.7% of those who had had sex at least once had also consulted a professional. Hence, only students who had a sex life had consulted a health professional.

Contrary to the above data is the fact that only 35% of this study’s population had consulted a specialist on contraception matters. Besides seeing a health professional, it would seem that our population also received advice on family planning from other sources.

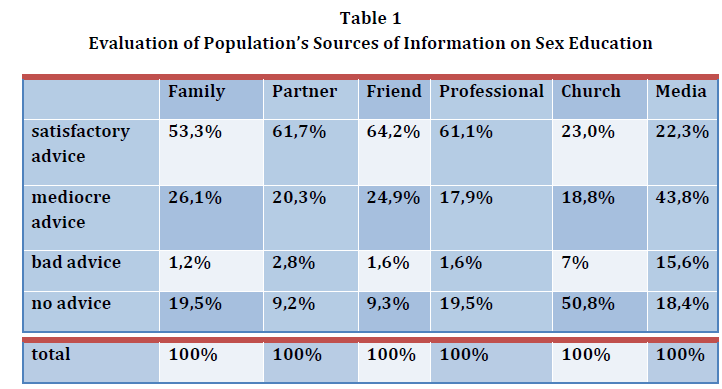

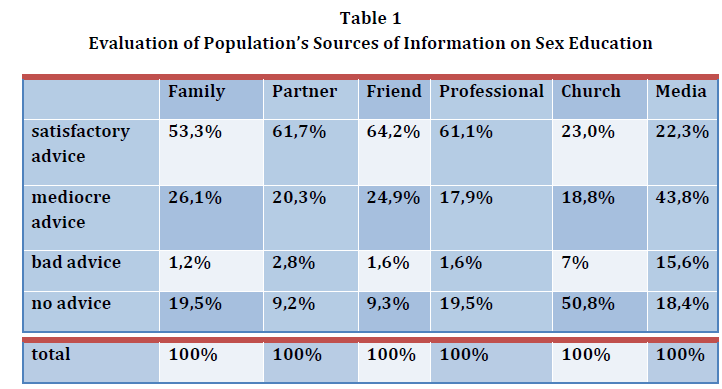

In table 1 it is shown that family, partners, friends and professionals were deemed to be satisfactory sources of information. The percentage of the population receiving advice from their partners is particularly high at 67.7%, i.e. on the basis of this specific sample, the respondent’s partner was deemed to be the source of the most satisfactory information.

As to the media, although a plethora of information comes from this source, the majority of respondents seemed reticent, with 43.8% rating advice from this source as mediocre. 50.8% of our population stated that they did not receive advice from the church. The question as to whether they had ever become pregnant or made their partner pregnant was left unanswered by approximately 20%.

There was no correlation between the answer to the question as to whether a family planning professional had been consulted and respondents’ geographical origin, department of studies, semester or gender. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that the number of students who consulted a professional increased along with the number of semesters students had studied, though this was not a statistically significant result, as can be seen in the following diagram.

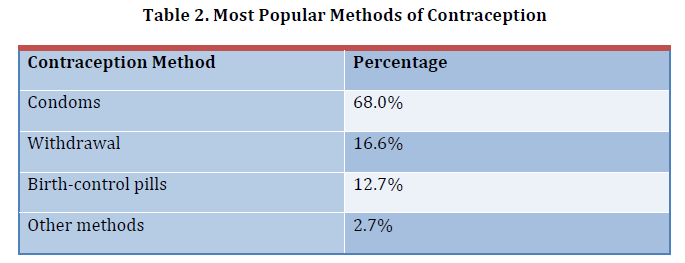

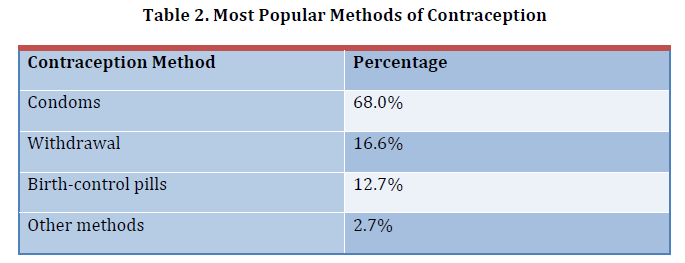

Diagram 1 shows that 41% of 1st semester students were interested in information about family planning matters, whereas the respective figure for students in their final semester was 51.2%. As to contraceptive methods, the most common is the condom, which was the most popular choice and was used by 68% of the population, as it is shown in Table 2.

Diagram 1: Students who consulted a professional according to the number of semester

The percentage of respondents who used withdrawal as a contraceptive method was also relatively high at 16.6%.

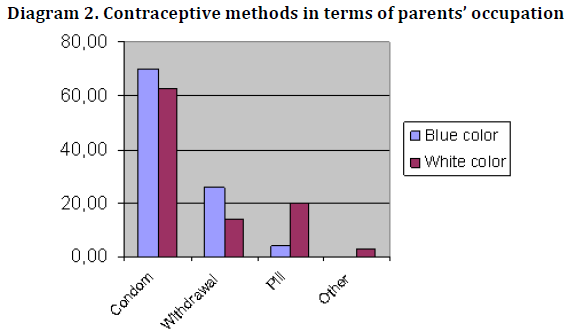

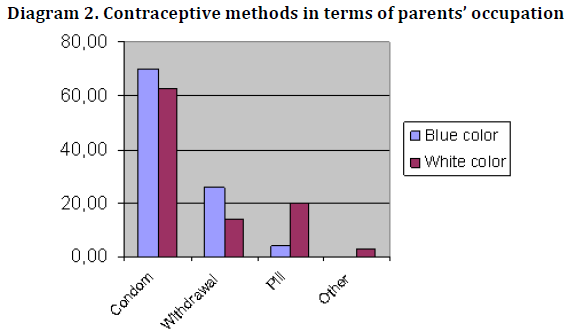

In Diagram 2 it is shown that the method of contraception used by these students was also influenced by their parents’ background. Students whose parents had a high level of education used oral contraceptives 4 times more often than other students (x² =9.72, p= 0.021). Furthermore, withdrawal was the most popular form of contraception for students whose parents had an inferior educational background.

Diagram 2: Contraceptive methods in terms of parents’ occupation

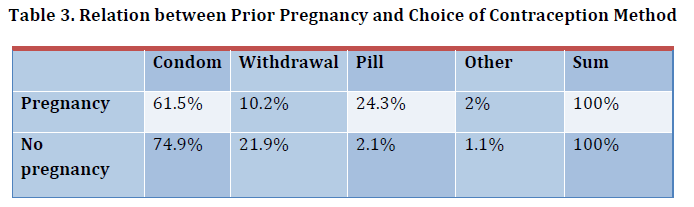

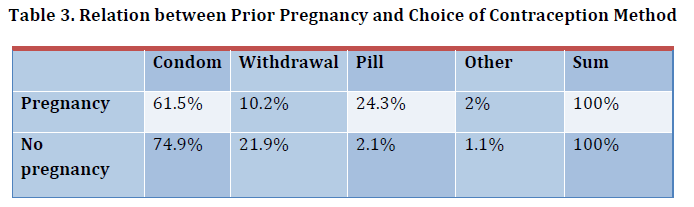

In the following Table 3 we show how a previous pregnancy influenced respondents’ choice of contraception methods.

Condom use was high, whether there had been a previous pregnancy or not. Withdrawal was used as a contraceptive method by 21.9% of our population, but when there had been a prior pregnancy, use of this method dropped to a mere 10.2%. On the other hand, use of birth?control pills seems to increase drastically as a result of a pregnancy, reaching 24.3%.

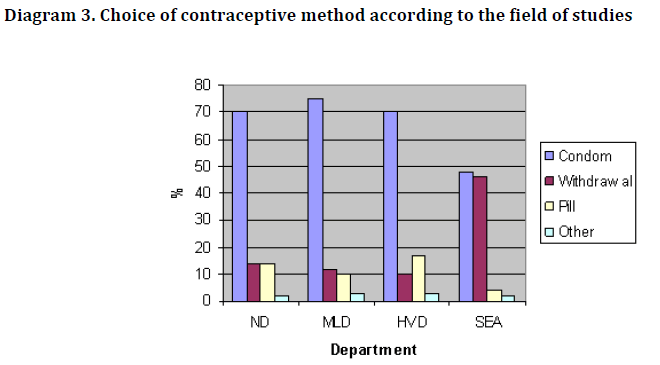

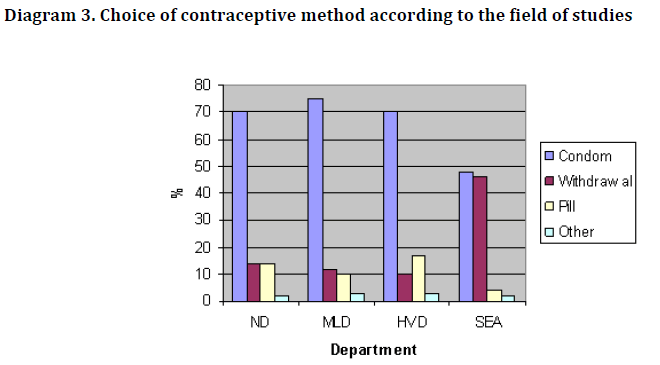

In Diagram 3, respondents’ choice of contraceptive method differed according to their field of studies. Thus, withdrawal is particularly common among SEA students, 7.8% of whom had been confronted with unwanted pregnancy, while the corresponding percentage for SHCP, where the method was less popular, is 5.2%. It is interesting that the respective figure for men who stated that their partner had become pregnant was 9.1% to 10.4%. Choice of contraception was not influenced by place of residence (p = 0.12), years of study (p = 0.282) or whether or not a family planning specialist had been consulted (p = 0.225).

Diagram 3: Choice of contraceptive method according to the field of studies

Discussion

The average age of the population studied was 21.1 ± 2.45 years, as is usual in similar research. At this age sexual activity is intense and partners change frequently, and hence it is interesting to study young people’s opinions and behavior. [14?16]

91.1% of our population argued that sex education should begin during adolescence, something that was also found in a study carried out in Scotland, where the majority of respondents was not fully informed about contraceptive methods, and 18% had not even used any contraception whatsoever during their last sexual encounter. [17,18]

65.6% of the respondents in the present study felt that it is most appropriate for physicians to provide sex education, although only 35% had ever consulted a health professional on contraception matters. Clearly, however, with the passing of time young people are becoming more fully and accurately informed on matters of sex education. [19,20]

The present study shows also that physicians and family were rated as satisfactory sources of information and advice, whereas the media and the church were deemed to be mediocre to unsatisfactory.

Research has shown that the population’s attitude will change as a result of a sex educational program, expressing great interest in further information on sexual health and contraceptive issues [21], this pertaining in particular to when the information source in question is a specialized health care professional offering an organized and valid information program. [22]

In this study, the answer to the question as to whether respondents had consulted a professional does not appear to be related to their origin, as 94% were Greek citizens and 96% Orthodox Christians. However, there would seem to be a great difference in the information received about contraception and sexually transmitted diseases when comparing populations from different continents. [23] Similar data can be gleaned from a study of groups of students from South Africa and Australia. [24] As to consulting health care professionals, the number of students who have increases with each semester of studies, and this is obviously because students become more informed during the course of their studies and thus devote more thought to these issues. As a result, these individuals’ awareness is heightened while at the same time making them feel more responsible. [25]

On the other hand, those who do not have a sex life are less willing to consider using condoms, according to other studies. [26,27]

As our results demonstrate in Table 2, the most popular method of contraception with 68% of respondents was the condom. This was to be expected, as it is an inexpensive, simple and effective method without side effects. [28]

As far as birth?control pills are concerned ?Diagram 2?, those whose parents’ educational background was superior were four times more likely to choose them.

Our findings have also shown that the percentage of our population who used withdrawal as a method of contraception dropped by 50 % when an unwanted pregnancy had occurred. This aspect demonstrates that information is not sufficient, since a relatively large percentage, 21.9% (18), would seem to trust this specific method, which has been documented as one of the most ineffective and in addition is dangerous as it offers no protection against sexually transmitted diseases. [29] Use of oral contraceptives approached 24.3% when a previous pregnancy had occurred, but was otherwise used by a mere 2.1% of respondents. This means that although this is a credible method of contraception, it is not a preferred method, presumably due to a lack of information and reluctance to approach health care professionals, who have naturally been consulted in the cases where pregnancy occurred.

The choice of contraceptives was different according to area of studies, as was to be expected. Withdrawal is preferred by SEA students, whereas SHCP students take a different stance, possibly because they become more fully informed during the course of their studies. Respondents’ place of residence does not appear to influence choice of contraceptive method in this study. This result does not agree with other research according to which geographical areas play a significant role, especially in terms of condom use in South Africa. [15,30?32]

Study semester does not influence choice of contraceptive method either in our study. In a similar study carried out over a period of 10 years on female students, it was found that attitudes toward contraception changed, resulting in a drop in sexually transmitted diseases and abortions from 26% to 14% and from 11% to 5.5% respectively. [33]

In general, as has been found in other studies as well, using contraception causes anxiety. This is especially true of female condoms, and is essentially due to a lack of information on how to use them and the protection they provide against sexually transmitted diseases. [34?40]

In conclusion, it was perhaps to be expected that choice of contraceptive method would be influenced by the students’ socio?economic situation. Those whose parents’ educational background was superior were four times more likely to choose birth?control pills, meaning that they had the opportunity to consult a health care professional who prescribed them. [41]

On the other hand, withdrawal, though an unreliable method, is the most popular among students whose parents have an inferior socio?economic background, probably because it involves no cost and there is widespread ignorance about its consequences. [37]

In summary, 80.7% of our sample appears to be familiar with the goal of Planned Parenthood, and sex education should begin during adolescence according to the overwhelming majority of those interviewed. However, only 35% of our population had ever consulted a health care professional on contraception, but rather partners and friends were deemed to be the most satisfactory sources of information.[42]

5272

References

- Solorio MR, Yu H, Brown ER, Becerra L, Gelberg L. A comparison of Hispanic and white adolescentnfemales’ use of family planning services in California, Perspect Sex Reprod Health, Jul‐Aug 2004, 36n(4): 157‐61

- Khawaja NP, Tayyeb R, Malik N. Awareness and practices of contraception among Pakistani womennat a Hending a tertiary care hospital, J Obstet Gynaecol. Ayg 2004, 24 (5): 564‐7

- Mosher WD, Contraceptive practice in the United States, 1982‐1988, Family Planning Perspectives, 1990, 22(5): 198‐205; and Peterson LS, Contraceptive use in the United States: 1982‐1990, AdvancenData from Vital and Health Statistics, 1995, No. 260.

- Ventura SV et al., Trends in pregnancies and pregnancy rates: estimates for the United States, 1980‐n1992, Monthly Vital Statistics Report, 1995, Vol. 43, No. 11, Suppl.

- Mosher WD and Pratt WF, Contraceptive use in the United States, 1973‐1988, Advance Data fromnVital and Health Statistics, 1990, No. 182.

- Jones EF and Forrest JD, Contraceptive failure rates based on the 1988 NSFG, Family PlanningnPerspectives, 1992, 24(1): 12‐19.

- Bachrach CA, Contraceptive practice among American women, 1973‐1982, Family PlanningnPerspectives, 1984, 16(6): 253‐256; Mosher WD and Bachrach CA, Contraceptive use: United States,n1982, Vital and Health Statistics, 1986, Series 23, No. 12; and Mosher WD, 1990, op. cit. (see referencen1).

- Comparison of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevalence by Reported Condom Use: Errors AmongnConsistent Condom Users Seen at an Urban Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinic, Sexually TransmittednDiseases 2004; 31(9): 526‐532, September 2004.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency contraception for women at risk ofnunintended and preventable pregnancy, Ann Emerg Med, Jul 2005, 46 (1): 103

- Rosenberg KD, Demunter Jh, Liu J. Emergency contraception in Emergency Departments innOregon, 2003, Am J Public Health, Jun 2005, 28.

- Raftopoulos V. et al. Scale validation methodology. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 2002, 19(5):577–n589.

- Marston C, Meltzer H, Majeed A. Impact on contraceptive practice of making emergency hormonalncontraception available over the counter in Great Britain: repeated cross sectional surveys, BMJ, Juln2005

- sokrataki, f., tzokas, g. hliaoutakis, i. “contraceptive behaviour and attitudes among youngnathenians”. iatriki. 1994, vol. 65, issue 5, pp. 483 – 488

- Bosompra, ‐K. Determinants of condom use intentions of university students in Ghana: annapplication of the theory of reasoned action. Soc‐Sci‐Med. 2001 Apr; 52(7): 1057‐69.

- Poulin, ‐C; Graham, ‐L. The association between substance use, unplanned sexual intercourse andnother sexual behaviors among adolescent students. Addition. 2001Apr; 96(4): 607‐21

- Langille, ‐D ‐B; Denlaney, ‐M‐E. Knowledge and use of emergency postcoital contraception bynfemale students at a high school in Nova Scotia. Can‐J‐Public‐Health.2000 Jan‐Feb; 91(1): 29‐32

- Ambegaokar M, Lush L. Family planning and sexual health organizations: management lessons fornhealth system reform. Health Policy Plan. 2004 Oct: 19 Suppl 1: i22‐i30

- National Report of Greece – Women’s position in Education – Health – Employment

- Salakos N, Roupa Z, Sotiropoulou P, Grigoriou O. Family planning and psychosocial support forninfertile couples. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004 Mar; 9(1): 47‐51

- Muia,‐E; Ellerston,‐C; Clark,‐S; Lukhando,‐M; Elul, Olenja,‐J; Westley,‐ What do family planningnclients and university students in Nairobi, Kenya, know and think about emergency contraception?nAfr‐J‐Reprod‐Health. 2000 Apr; 4(1): 77‐87

- Bazargan,‐M: Kelly,‐E‐M: Stein,‐J‐A: Husaini,‐B‐A: Bazargan,‐S‐H Correlates of HIV risk‐takingnbehaviors among African‐American college students: the effect of HIV knowledge, motivation, andnbehavioral skills. J‐Natl‐Med‐Assoc. 2000 Aug; 92(8): 391‐404

- Grammich C, Da Vanzo J, Stewart K. Changes in American opinion about family planning. Stud FamnPlann. 2004 Sep; 35(3): 161‐206

- Smith, ‐A‐M: de‐Visser, ‐R: Akande,‐ Rosenthal,‐D: Moore,‐S Australian and South Africannundergraduates’ HIV‐related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Arch‐Sex‐Behav. 1998 Jun: 27(3):n279‐94

- Von Sadovszky V, Keller M, McKinney K. College Students’ Perceptions and Practices of SexualnActivities in Sexual Encounters, Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 2002, 34(2): 133‐138

- Troth, ‐A; Peterson, ‐C‐C. Factors predicting safe‐sex talk and condom use in early sexual relationships. Health‐Commun. 2000; 12(2): 195‐218

- Peltzer, ‐K. Factors affecting condom use among serious secondary school pupils in South Africa.nCent‐Afr‐J‐Med. 2000 Nov: 46(11): 302‐8

- Grimes D, Gallo MN, Grigorieva V, Nanda K, Schulz K. Fertility awareness‐based methods forncontraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 Oct 18; 4: CD004860

- Wawer M et al., Control of sexually transmitted diseases for AIDS prevention in Uganda: anrandomized community trial, Lancet, 1999, 353 (9152): 525‐535

- Peltzer, ‐K. Factors affecting behaviors that address HIV risk among senior secondary schoolnpupils in South Africa. Psycol‐Rep. 2001 Aug; 89(1): 51‐6

- Peltzer, ‐K. Factors affecting condom use among South African university students East‐Afr‐Med‐J.n2000 Jan: 77(1): 46‐52

- Peltzer, ‐K. Knowledge and practice of condom use among first year students at University of thenNorth, South Africa. Curationis. 2001 Mar: 24(1): 53‐7

- Tyden,‐T; Olsson,‐S; Haggstrom‐Nordin,‐E. Improved use of contraceptives, attitudes towardnpornography, and sexual harassment among female university students. Womens‐Health‐Issues. 2001nMar‐Apr; 11(2): 87‐94

- Dilorio, ‐C; Dudley,‐W‐N; Soet,‐j; Watkins,‐J; Maibach,‐E A social cognitive‐based model for condomnuse among college students. Nurs‐Res. 2000 Jul‐Aug; 49(4): 208‐14

- Civic, ‐D. College students΄ reasons for nonuse of condoms within dating relationships. J‐Sex‐nMarital‐Ther. 2000 Jan‐Mar; 26(1): 95‐105

- Traifimow,‐D Condom use among US students: the importance of confidence in normative andnattitudinal perceptions. J‐Soc‐Phychol. 2001 Feb; 141(1): 49‐59

- Mayaud P, Hawkes S and Mabey D. Advances in control of sexually transmitted diseases inndeveloping countries, Lancet, 1998, 351 (suppl III): 29‐32

- Creatsas G. Contraception for adolescents 2003. Endocr Dev. 2004;7:225‐32.38. Valappil T,nKelaghan J, Macaluso M, Artz L, Austin H, Fleenor ME, Robey L, Hook EW 3rd. Female Condom andnMale Condom Failure Among Women at High Risk: Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Sex Transm Dis.n2005 Jan; 32(1): 35‐43

- Choi KH, Wojcicki J, Valencia‐Garcia D. Introducing and negotiating the use of female condoms innsexual relationships: qualitative with women attending a family planning clinic. AIDS Behav. 2004nSep; 8(3): 251‐61

- Ujah IA. Contraceptive intentions of women seeking induced abortion in the city of Jos, Nigeria. JnObstet Gynaecol. 200; 20(2): 162‐6

- Deligeoroglou E, Michailidis E, Creatsas G. Oral contraceptives and reproductive systemncancer.Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003 Nov;997:199‐208.

- Creatsas G, Elsheikh A. Adolescent pregnancy and its consequences. Eur J Contracept ReprodnHealth Care. 2002 Sep;7(3):167‐7