Keywords

Macrolide antibiotics; staphylococci; erm gene; msr gene.

Introduction

Macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin, clarithromycin and azithromycin have been widely used in treatment of respiratory tract infections caused by Gram-positive pathogens including Staphylococcus spp. [1-2]. MLS antibiotics exert their antimicrobial action by inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis which is achieved by reversible binding of these agents to the P-site of the 50S subunit of the bacterial ribosome [1-3].

There are three different mechanisms responsible for bacterial resistance to MACs in staphylocooci: (1) Target site modification mediated by erm gene; (2) active efflux mediated by msr A gene; and (3) enzymatic inactivation of antibiotic mediated by esterases (encoded by ere gene) or phosphotransferases (encoded by mph gene) [4-5]. The first mechanism confers resistance not only to MACs, but also to lincosamides and streptogramin type B (MLS phenotype), which is achieved by dimethylation of specific adenine residue in 23S rRNA molecule in the ribosome [4,6-7]. The expression of erm gene can be either constitutive (cMLS phenotype), or inducible (iMLS phenotype) [4]. The second mechanism confers resistance to either MAC antibiotics only (M phenotype) or MACs and streptogramin type B (MS phenotype) [4]. The MAC resistance genes as erm and msr genes are widely distributed in staphylococci of humans, and located on small multicopy plasmids [8-12] erm genes are mostly responsible for erythromycin resistance in different Staphylococcus spp. strains and are borne by plasmids. Also, to date, the only efflux proteins responsible for acquired macrolide resistance characterized in Staphylococccus spp. are ABC transporters encoded by plasmid borne msr genes [13].

The emergence of antibiotic resistance among pathogenic bacteria, either in hospital or community- acquired infections is considered to be a major public health problem. Plasmids, which are an extrachromosomal pieces of DNA, can replicate independently of the genome, and are considered of great importance in the spread of antibiotic resistance genes, which result in the acquisition of resistance to many antibiotics [14]. Due to their capability of horizontal gene transfer between different species and genera, plasmid-mediated resistance is considered to be a significant problem in the spread of antibiotic resistance among pathogenic bacteria [14-15].

The aim of this study was to detect macrolide target site modification gene (erm gene) and macrolide active efflux gene (msr gene) on plasmids extracted from Staphylococcus spp recovered from patients with lower respiratory tract infections (LRIs) in Egypt. Specific PCR primers were used to detect target site modification gene erm (erythromycin ribosomal methylase), and active-efflux gene msr.

Materials and Methods

A total of 189 clinical bacterial isolates, recovered from patients with LRIs from the Microbiology diagnostic laboratories of Al-Sadr (Abbassia) and Al- Demerdash Hospitals in Egypt during the period of 2010 to 2012, were studied. The history sheets of all patients were examined, and all patients read and signed an “informed consent” form before the beginning of the study verifying their acceptance for using their data for research purpose.

Microbiological cultures

The collected isolates were obtained from sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens of both pediatric and adult patients by culture on 5% sheep blood agar plates and incubating them overnight at 37°C. Mannitol salt agar plates and coagulase test were used for identification of Staphylococcus aureus. The isolates were preserved in glycerol broth at -20°C till use.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

The susceptibilities of the collected isolates were determined by disc diffusion method on Mueller hinton agar according to clinical and laboratory standard institute (CLSI). The tested antibiotics (BBL™ Sensi-Disc™, USA) include: erythromycin (15 μg), clarithromycin (15 μg), azithromycin (15 μg) and clindamycin (2 μg). The inducible type of resistance was demonstrated using double-disc diffusion test (D test) by placing clindamycin discs and erythromycin discs at distances of 16-25 mm followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 hrs [16].

Plasmid profile analysis

Analysis of plasmid-DNA for the resistant bacterial isolates was performed by plasmid DNA extraction followed by direct agarose gel electrophoresis of the extracted plasmids [17]. Plasmids were extracted by alkaline lysis method as described by Birnboim and Doly [18] using GeneJet Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Fermentas, USA) according to the manufacturer’s manual.

Conventional Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

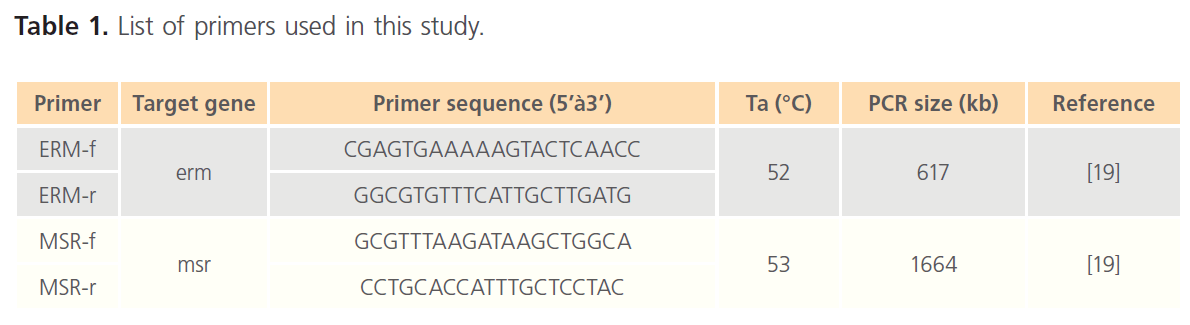

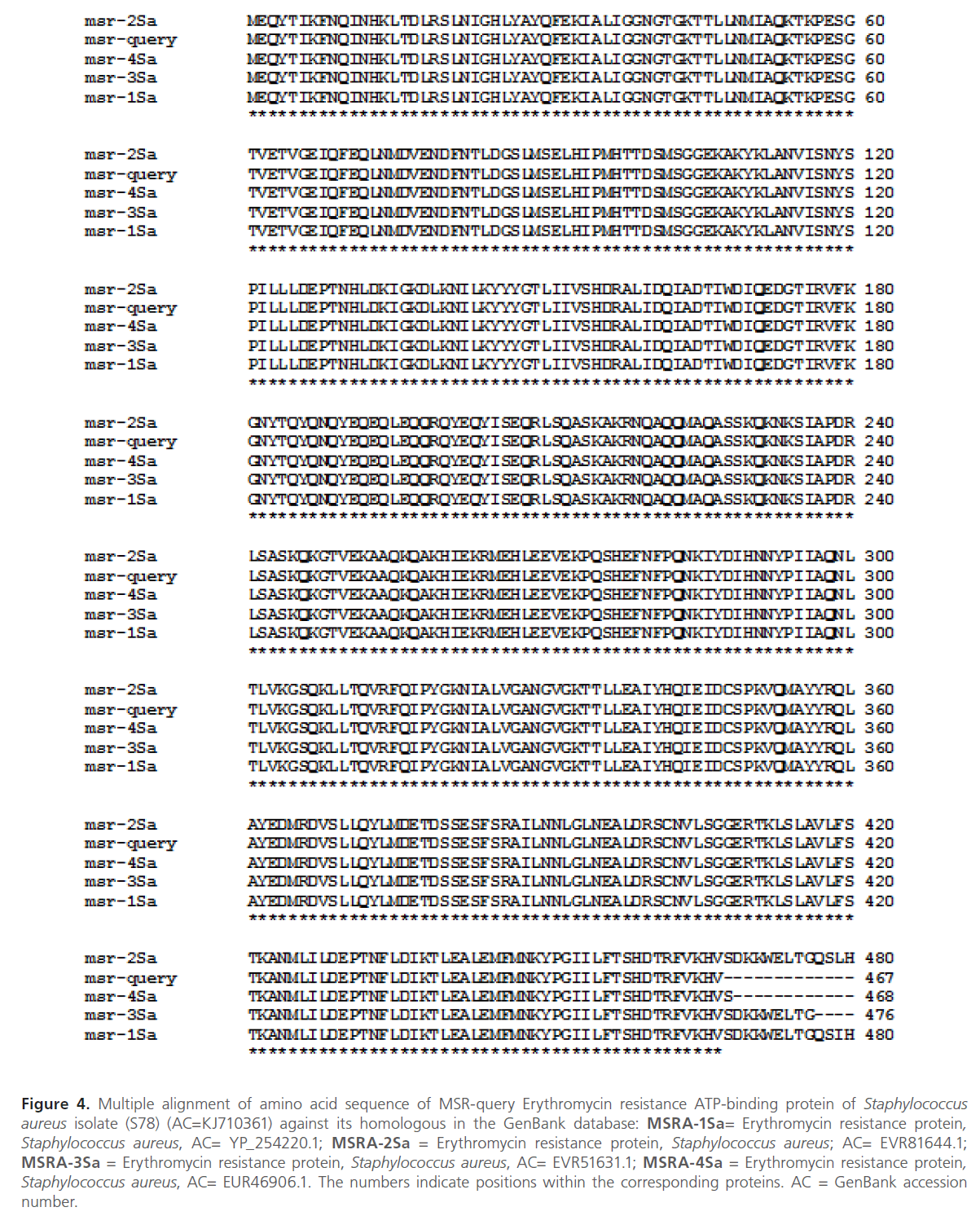

Amplification of the selected resistance genes was performed through PCR, using plasmid-DNA of each resistant strain as a template and the primers outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. List of primers used in this study.

PCR amplification was carried with the cycling parameters as follows: After an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 4 min, 30 cycles of amplification were performed as follows: Denaturation at 95°C for 30s, annealing temperature at 53°C for 45 sand extension temperature at 72°C for 1 min, this was followed by I cycle of final extension at 72°C for 5 min, and finally the reaction was hold at 4°C for 10 min. The sizes of PCR products of these genes were analyzed by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis containing ethidium bromide (0.5μg/ml).

Sequencing of PCR products

The obtained PCR products were purified using GeneJET™ PCR Purification kit (Fermentas, USA) at Sigma Scientific Services Company, Egypt. Finally, sequencing was done at GATC Biotech Company (Germany), through Sigma Scientific Services Company (Egypt) by the use of ABI 3730xl DNA Sequencer.

Computer programs used for sequence analysis

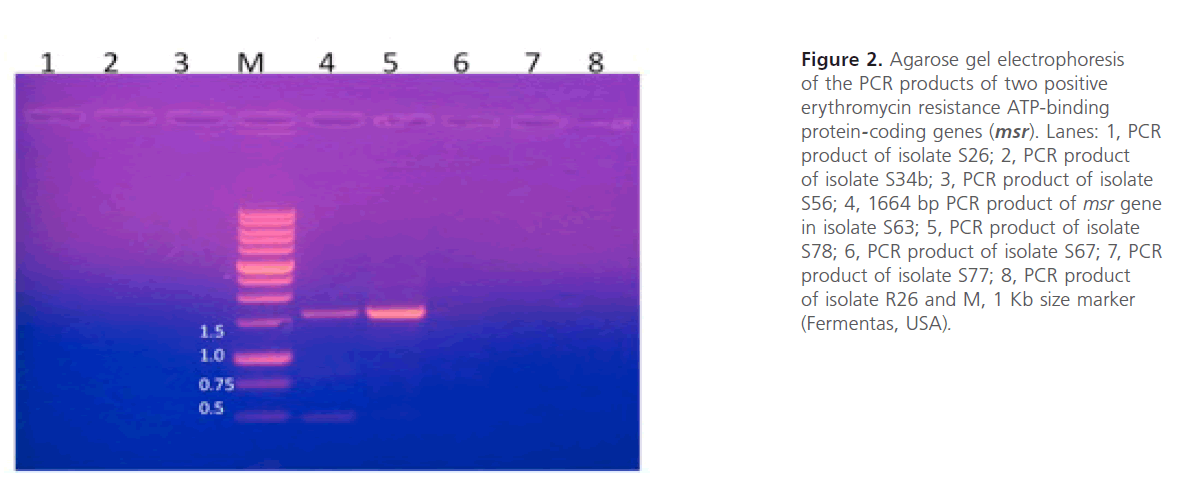

The obtained sequence files (forward and reverse) were analyzed using the following programs: Staden-package program version 3 [20] was used for sequence assembly and formation of final contigs; Frameplot [21] for detection of the ORFs in the final contigs; Clustal W [22] for amino acid alignment. Finally DNA search in the GenBank database using BLAST (Basal Local Alignment Research tool) to visualize fully and/or partially conserved domains or regions within the macrolide resistance proteins products.

Results

Collection of bacterial isolates from clinical specimens

A total of 189 bacterial isolates were recovered from sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens from patients with LRIs.

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests and detection of Staphylococcus spp. resistant isolates

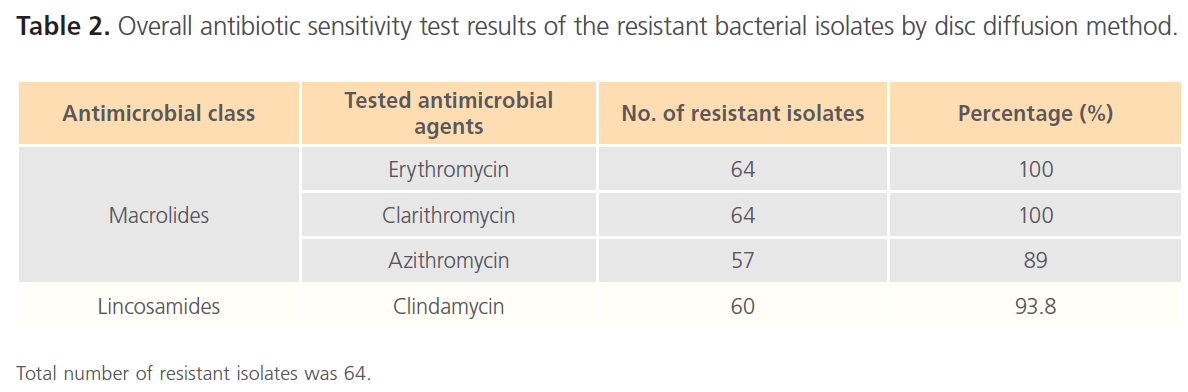

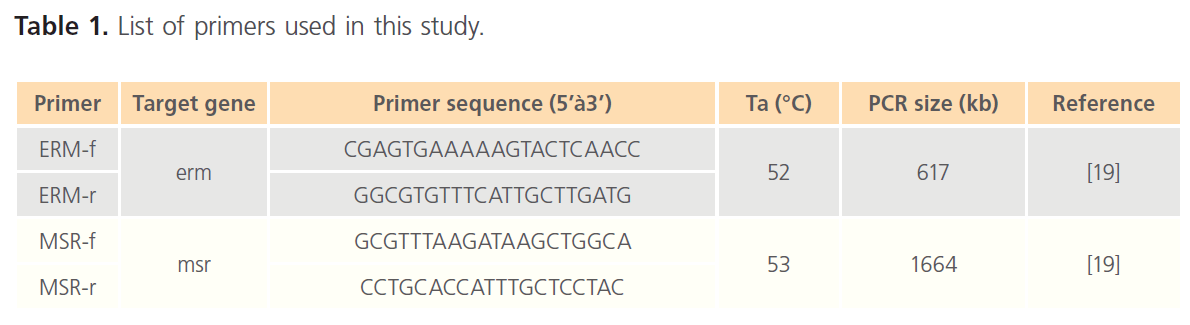

Using Gram-stain, 47 isolates, out of 189 collected isolates, were found to be Gram-positive (24.9%), 64 isolates (33.9%) were found to be resistant to the tested antibiotics. Among the resistant isolates, 12 isolates (18.7%) were found to be Gram-positive, including 8 isolates (n=8/64; 12.5%) which were identified to be Staphylococcus spp. Out of these 8 isolates, 7 isolates (S34b, S56, S63, S67, S77, S78 and R26) were confirmed to be Staphylococcus aureus based on yellowish growth on mannitol salt agar and positive coagulase test, while one isolate (S26) was identified as coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. The results of antibiotic sensitivity test were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Overall antibiotic sensitivity test results of the resistant bacterial isolates by disc diffusion method.

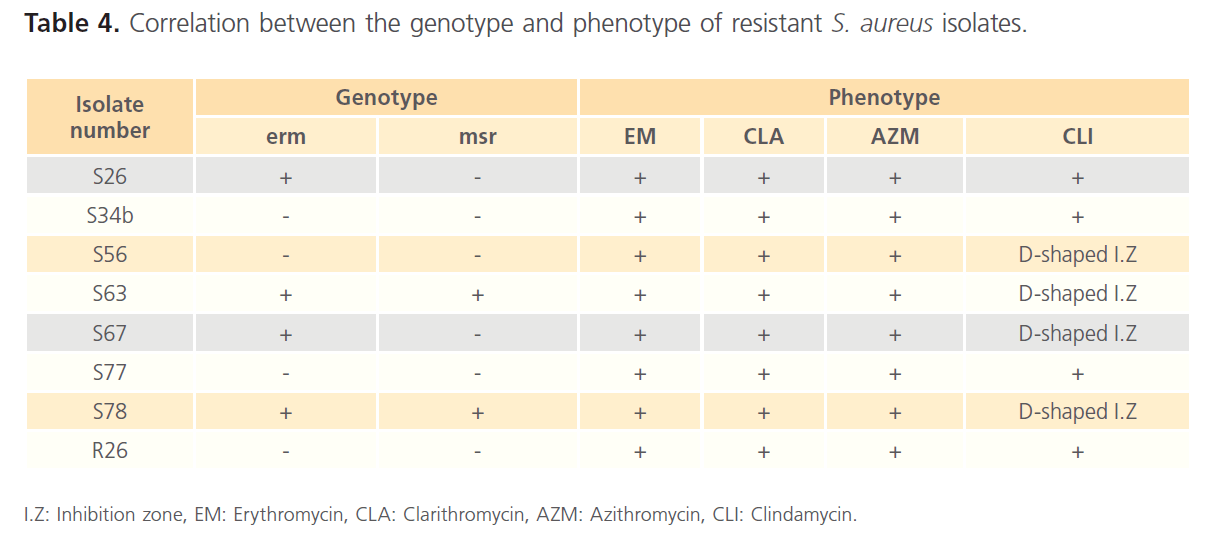

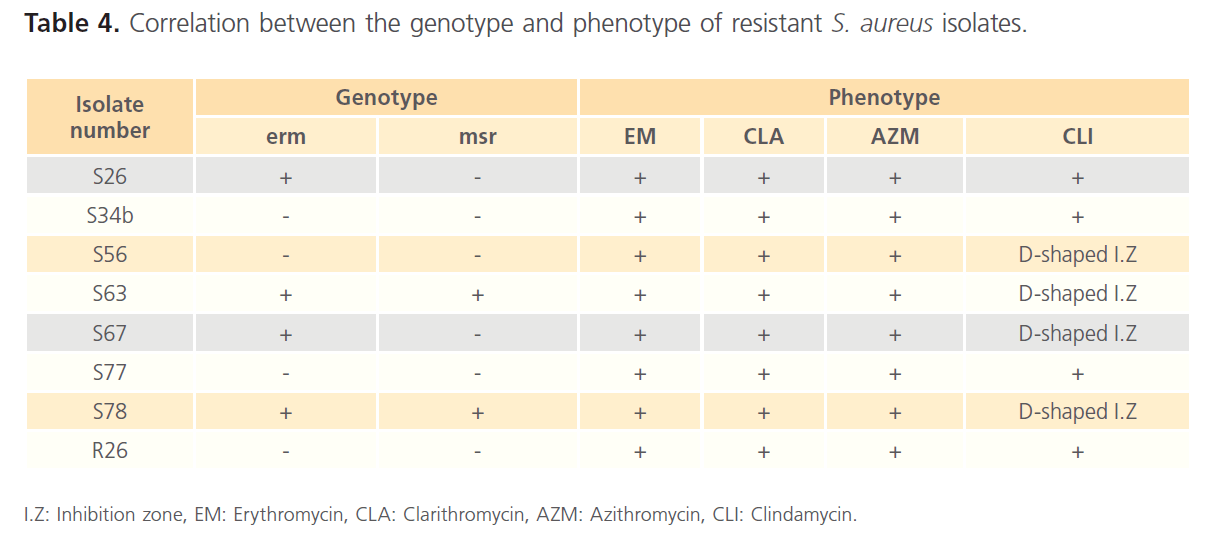

Among the 8 resistant Staphylococcus spp isolates, 4 isolates (S26, S34b, S77 and R26) showed complete resistance to all tested antibiotics. While the other 4 isolates (S56, S63, S67 and S78) showed D-shaped inhibition zone around clindamycin discs.

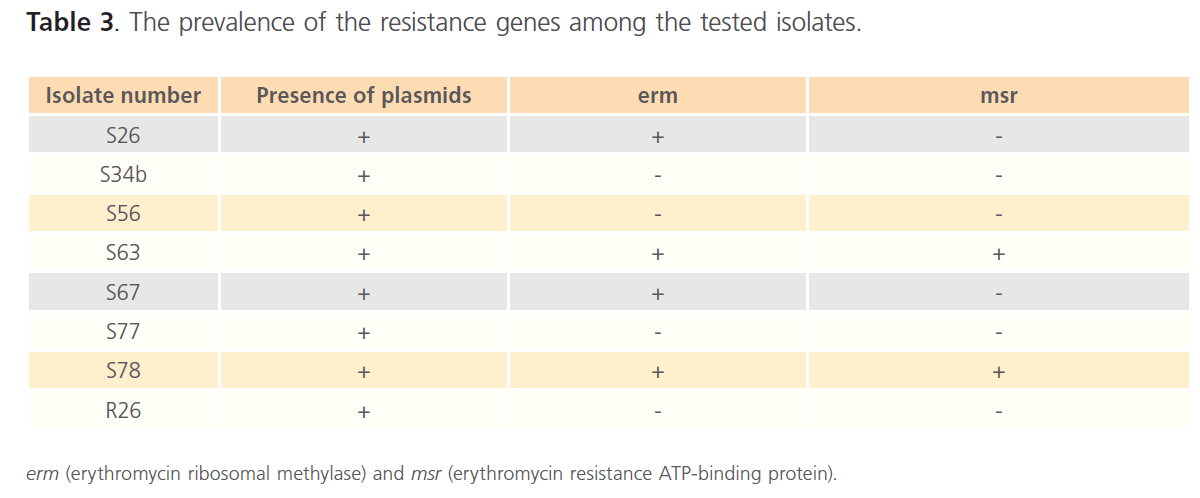

Plasmid profile analysis and PCR

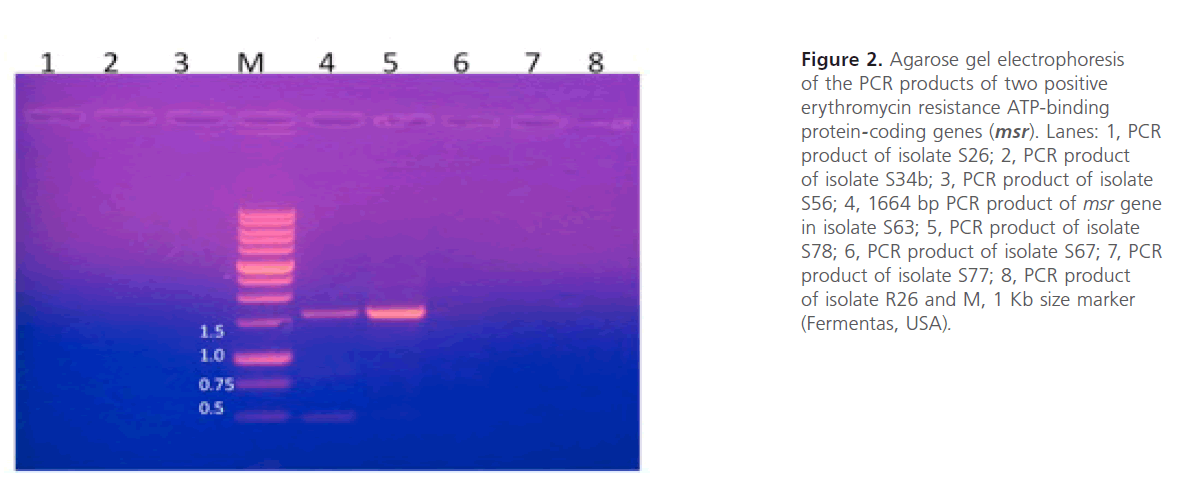

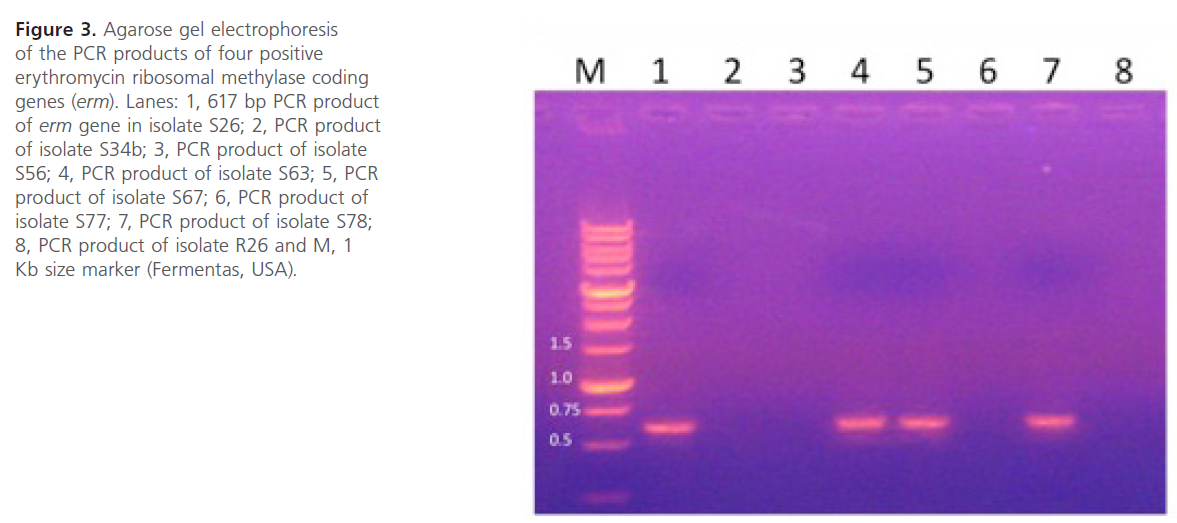

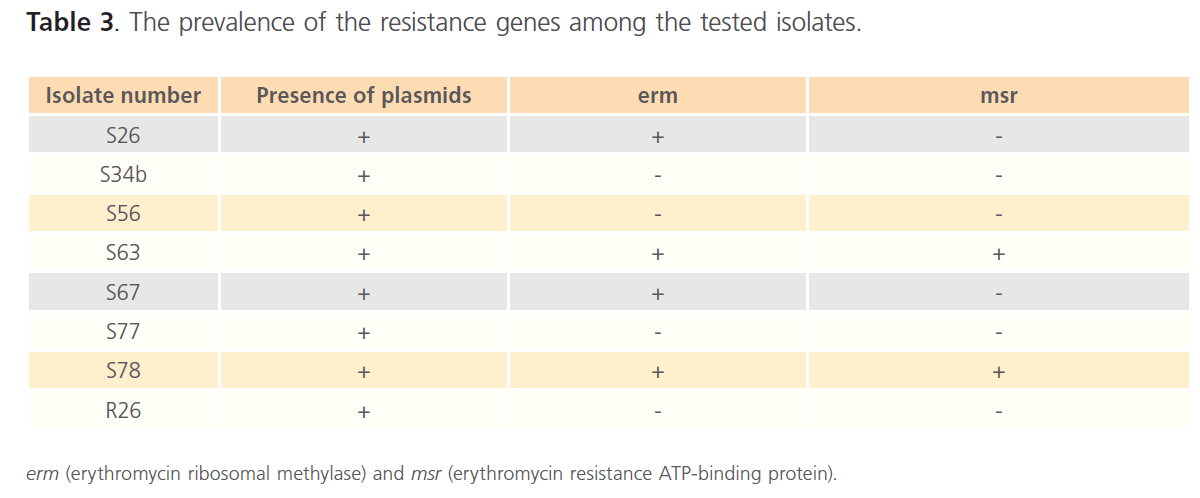

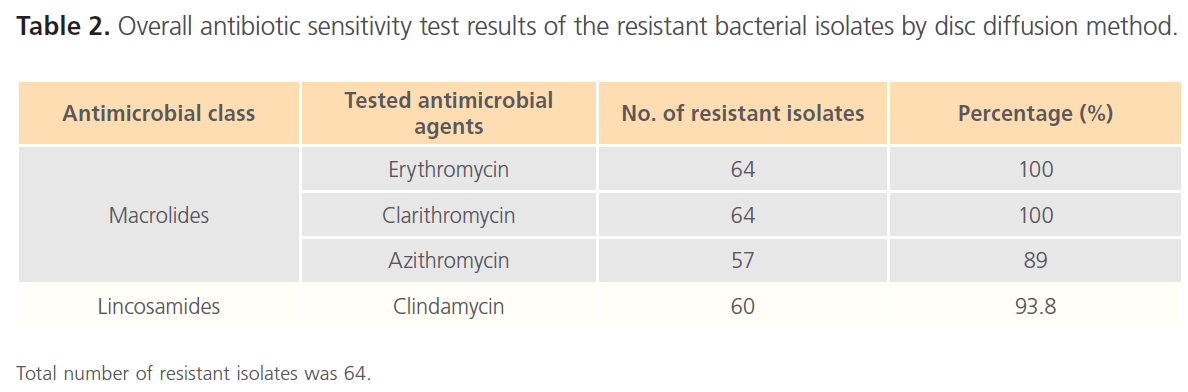

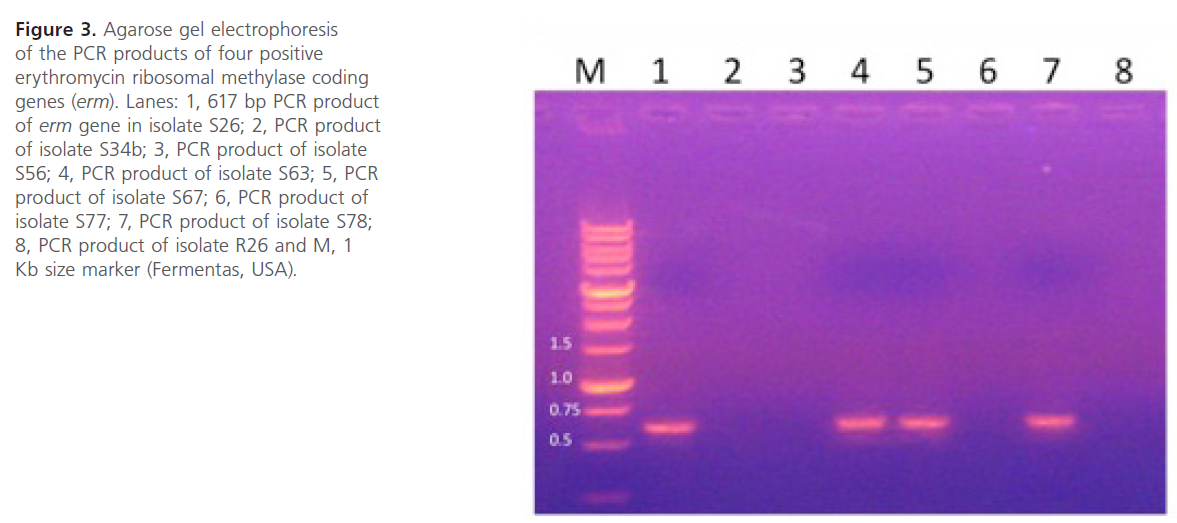

Plasmid extraction, carried out on Staphylococcus spp resistant isolates, revealed the presence of plasmids in the 8 resistant isolates. The extracted plasmids were used as template for PCR using the primers listed in Table 1. The gel electrophoresis of PCR products showed the presence of msr and erm genes (figure 2 and figure 3). The prevalence of the resistance genes among the tested isolates were summarized in Table 3. The correlation between the genotype and phenotype of resistant isolates was shown in Table 4.

Figure 2: Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products of two positive erythromycin resistance ATP-binding protein-coding genes (msr). Lanes: 1, PCR product of isolate S26; 2, PCR product of isolate S34b; 3, PCR product of isolate S56; 4, 1664 bp PCR product of msr gene in isolate S63; 5, PCR product of isolate S78; 6, PCR product of isolate S67; 7, PCR product of isolate S77; 8, PCR product of isolate R26 and M, 1 Kb size marker (Fermentas, USA).

Figure 3: Agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR products of four positive erythromycin ribosomal methylase coding genes (erm). Lanes: 1, 617 bp PCR product of erm gene in isolate S26; 2, PCR product of isolate S34b; 3, PCR product of isolate S56; 4, PCR product of isolate S63; 5, PCR product of isolate S67; 6, PCR product of isolate S77; 7, PCR product of isolate S78; 8, PCR product of isolate R26 and M, 1 Kb size marker (Fermentas, USA).

Table 3. The prevalence of the resistance genes among the tested isolates.

Table 4. Correlation between the genotype and phenotype of resistant S. aureus isolates.

Sequencing of PCR products

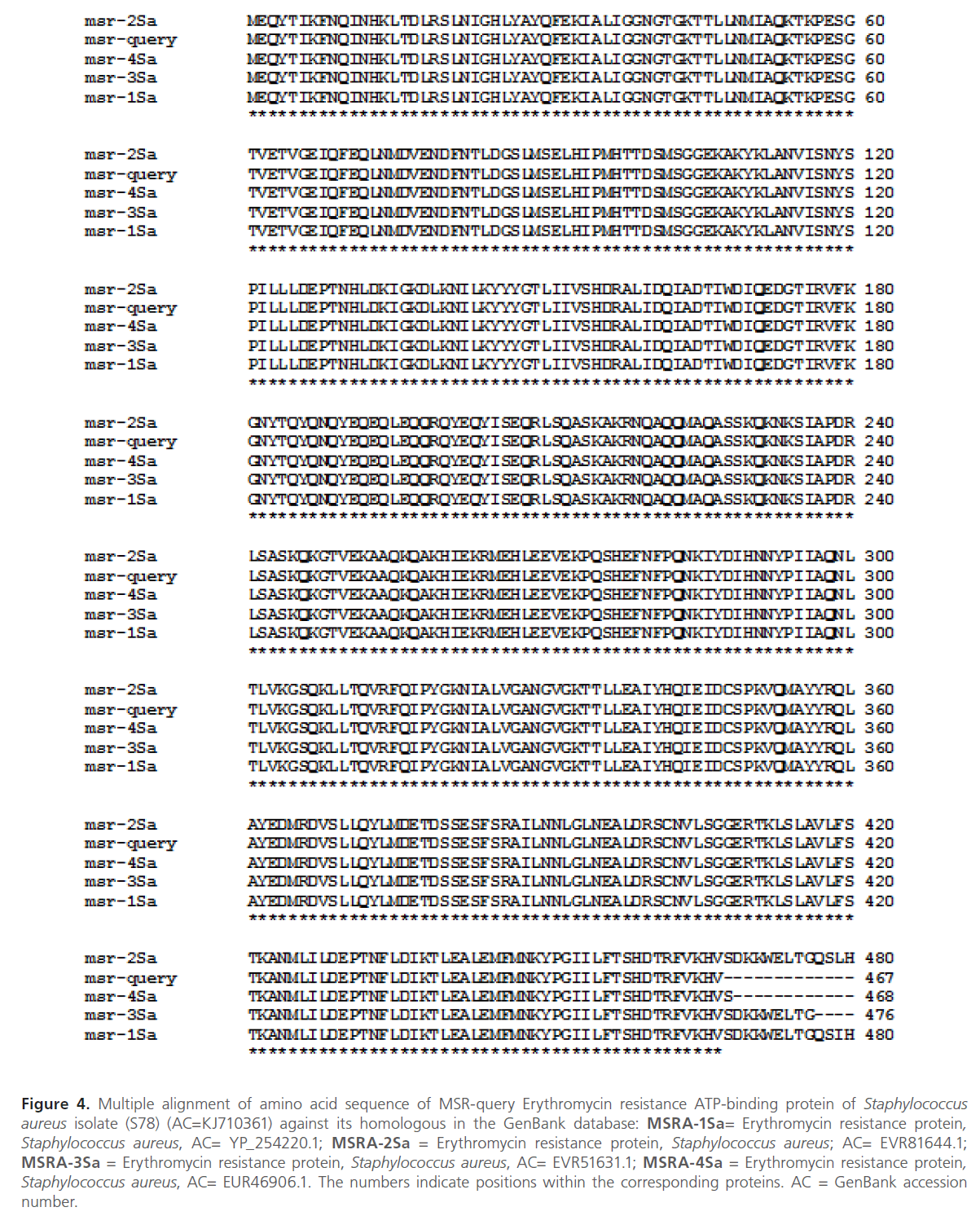

Further verification of the msr gene was performed by DNA sequencing of the PCR product obtained by using the plasmid extract from isolate S78 as a template for PCR. The sequence analysis revealed the presence of msr gene. The nucleotide sequence of msr gene was submitted to the nucleotide GenBank database, and given accession code KJ710361. The results of multiple sequence alignment of msr gene with its homologous proteins by using Clustal W software were shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Multiple alignment of amino acid sequence of MSR-query Erythromycin resistance ATP-binding protein of Staphylococcus aureus isolate (S78) (AC=KJ710361) against its homologous in the GenBank database: MSRA-1Sa= Erythromycin resistance protein, Staphylococcus aureus, AC= YP_254220.1; MSRA-2Sa = Erythromycin resistance protein, Staphylococcus aureus; AC= EVR81644.1; MSRA-3Sa = Erythromycin resistance protein, Staphylococcus aureus, AC= EVR51631.1; MSRA-4Sa = Erythromycin resistance protein, Staphylococcus aureus, AC= EUR46906.1. The numbers indicate positions within the corresponding proteins. AC = GenBank accession number.

Discussion

This study was concerned with the detection of different determinants of macrolide resistance in plasmids extracted from Staphylococcus spp. recovered from sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens from patients with LRIs in Egypt.

There are two main mechanisms of MLS resistance in staphylococci, which are: Target site modification due to erm genes, and active-efflux due to msr A gene [13,23-24]. msr gene affects only MACs (M phenotype) or MACs and streptogramin type B(MS phenotype). While, The expression of erm gene can be constitutive (cMLS phenotype) or inducible (iMLS phenotype) [25].

In this study, the antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the recovered Staphylococcus spp was carried out using disc diffusion method according to CLSI. 4 isolates (S26, S34b, S77 and R26) were found to be resistant to MACs as well as clindamycin (linosamide), which indicate cMLS resistance phenotype. The other 4 isolates (S56, S63, S67 and S78) showed flattening of the clindamycin inhibition zone towards an adjacent erythromycin disc by using double-disc diffusion test (D test), while, they are resistant to the other MACs, which indicate iMLS resistance phenotype.

The phenotype of MLS resistance, either constitutive or inducible, may show great variations based on the patient groups in different hospitals, and on geographical region. This variation may be attributed to several factors as: The inconsistent use of MACs in different hospitals, patient age and the origin of the tested isolate [26-27]. In our study, it was found that 4 resistant Staphylococcus Spp (50%) showed cMLS resistance. While, the other 4 isolates (50%) showed iMLS resistance. In study carried out in London by Hamilton-Miller et al. iMLS phenotype was the predominant phenotype (43%) followed by cMLS phenotype which was found in 24% of the isolates [28]. In another study conducted by Fiebelkorn et al. in Texas, cMLS phenotype was more prevalent (41.7%) followed by both iMLS and MS phenotypes (3.3% each) [29]. The high incidence of iMLS phenotype in this study may be attributed to the increased concurrent use of MAC and clindamycin antibiotics [25].

In addition to the phenotypic tests used for screening of MLS resistance, genetic tests were also carried out. It was found that the 8 resistant isolates showed plasmid bands upon plasmid extraction and running the extract on 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR was done on all 8 resistant isolates, using plasmid extracts as templates, to amplify the two plasmid-mediated genes: erm and msr. erm gene was more prevalent than msr gene among the 8 resistant isolates. The results revealed the presence of erm gene in 4 isolates (50%), and msr gene in only 2 isolates (25%). It was noticed that erm gene was more prevalent than msr gene. This finding was in accordance with the prevalence results in the study conducted in Turkey by Aktas et al. [26].

In this study, 3 resistant Staphlococcus spp isolates (S34b, S77 and R26) showed cMLS phenotype, and 1 isolate (S56) showed iMLS phenotype. However, PCR results, using the primers listed in table 1, were negative for erm genes. This study was concerned with plasmid-mediated genes and the PCR was carried out on plasmid extracts of the resistant isolates to detect plasmid-harbored genes. The resistance in the erm-negative isolates may be due to the presence of either erm or msr genes or both on the genomic-DNA. 3 isolates (S63, S67 and S78) were positive for erm genes, and showed iMLS resistance phenotype. While only 1 isolate (S26) was positive for erm gene, and showed cMLS phenotype. In inducible resistance, the bacteria produce inactive mRNA that is unable to encode methylase. The mRNA becomes active only in the presence of a macrolide inducer. While, in constitutive resistance, active methylase mRNA is produced in the absence of an inducer [13]. Induction is related to the presence of an attenuator upstream from the structural erm gene coding for the methylase [30].

The msr gene, responsible for M phenotype, was found in 2 isolates in this study (S63 and S78). However, these 2 isolates showed iMLS resistance phenotype. This may be due to the presence of erm genes in these isolates. So, the M phenotype of msr gene was masked by the iMLS phenotype of erm gene.

Therefore, results obtained from our study were of great significance regarding the prevalence of plasmid- mediated MAC resistance genes in staphlococci, which may result in horizontal transfer of MAC resistance genes among different gram-positive bacteria causing LRIs. Therefore, the reasons behind the prevalence of these plasmid-mediated genes among staphylococci have to be studied in order to limit the dissemination of macrolide resistance.

List of Abbreviations

erm= Erythromycin ribosomal methylase

LRIs= Lower resoiratory tract infections.

MACs= Macrolides.

MLS= Macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin type B..

44

References

- Steel HC, Theron AJ, Cockeran R, Anderson R, Feldman C. Pathogen- and Host-Directed Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Macrolide Antibiotics. Mediators of Inflammation; 2012.

- Kaneko T, Dougherty TJ, and Magee TV. Macrolide Antibiotics in Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry II, Taylor JB and Triggle DJ, Eds. Oxford: Elsevier; 2007, pp. 519-566.

- Mankin AS. Macrolide Myths. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2008; 11 (5).

- Chancey ST, Zhou X, Zahner D, Stephens DS. Induction of Efflux-Mediated Macrolide Resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2011; 55 (7): 3413-3422.

- Roberts MC. Update on macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin, ketolide, and oxazolidinone resistance genes. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2008; 282 (2): 147-159.

- Takaya A, Sato Y, Shoji T, Yamamoto T. Methylation of 23S rRNA Nucleotide G748 by RlmAII Methyltransferase Renders Streptococcus pneumoniae Telithromycin Susceptible.Antimicrobial Agents Chemotherapy 2013; 57 (8): 3789-3796.

- Thumu SCR, Halami PM. Acquired Resistance to Macrolide-Lincosamide-Streptogramin Antibiotics in Lactic Acid Bacteria of Food Origin. Indian Journal of Microbiology 2012; 52 (4): 530-537.

- Matsuoka M, Endou K, Kobayashi H, Inoue M, Nakajima Y. A plasmid that encodes three genes for resistance to macrolide antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998; 167 (2): 221-227.

- Matsuoka M, Inoue M, Endo Y, Nakajima Y. Characteristic expression of three genes, msr(A), mph(C) and erm(Y), that confer resistance to macrolide antibiotics on Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003; 220 (2): 287-293.

- Hauschild T, Lüthje P, Schwarz S. Characterization of a novel type of MLSB resistance plasmid from Staphylococcus saprophyticus carrying a constitutively expressed erm(C) gene. Vet. Microbiol. 2006; 115 (1-3): 258-263.

- Thong K, Hanifah Y, Lim K, Yusof M. ermA, ermC, tetM and tetK are essential for erythromycin and tetracycline resistance among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2012; 30 (2): 203.

- Hisatsune J, Hirakawa H, Yamaguchi Y, Fudaba Y, Oshima, M. et al. Emergence of Staphylococcus aureus Carrying Multiple Drug Resistance Genes on a Plasmid Encoding Exfoliative Toxin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013; 57 (12): 6131-6140.

- Leclercq R. Mechanisms of resistance to macrolides and lincosamides: nature of the resistance elements and their clinical implications. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2002; 34 (4): 482-492.

- Svara F, Rankin DJ. The evolution of plasmid-carried antibiotic resistance. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011; 11: 130.

- Thomas CM, Nielsen KM. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nature Reviews. Microbiology 2005; 3 (9): 711-721.

- Coutinho V de LS, Paiva RM, Reiter KC, de-Paris F, Barth AL, Machado, ABMP. Distribution of erm genes and low prevalence of inducible resistance to clindamycin among staphylococci isolates. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010; 14 (6): 564-568.

- Chart H. Methods in Practical Laboratory Bacteriology. CRC Press; 1994.

- Birnboim HC, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 1979; 7 (6): 1513-1523.

- Grivea IN, Sourla A, Ntokou E, Chryssanthopoulou DC, Tsantouli AG. et al. Macrolide resistance determinants among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from carriers in CentralGreece. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012; 12: 255.

- Staden R. The staden sequence analysis package. Molecular Biotechnology 1996; 5 (3): 233-241.

- Ishikawa J, Hotta K. FramePlot: A new implementation of the frame analysis for predicting protein-coding regions in bacterial DNA with a high G + C content. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1999; 174 (2): 251-253.

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research 1994; 22 (22): 4673-4680.

- Syrogiannopoulos GA, Grivea IN, Ednie LM, Bozdogan B, Katopodis GD. et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Macrolide Resistance Inducibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae Carrying erm(A), erm(B), or mef(A). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2003; 47 (8): 2699-2702.

- Van Bambeke F, Harms JM, Van Laethem Y, Tulkens PM. Ketolides: Pharmacological profile and rational positioning in the treatment of respiratory tract infections. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2008; 9 (2): 267-283.

- Adaleti R, Nakipoglu Y, Ceran N, Tasdemir C, Kaya F. et al. Prevalence of phenotypic resistance of Staphylococcusaureus isolates to macrolide, lincosamide, streptogramin B, ketolid and linezolid antibiotics in Turkey. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010; 14 (1): 11-14.

- Aktas Z, Aridogan A, Kayacan CB, Aydin D. Resistance to macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin antibiotics in staphylococci isolated in Istanbul, Turkey. Journal of Microbiology 2007; 45 (4): 286-290.

- Merino-Díaz L, de la Casa ÁC, Torres-Sánchez MJ, Aznar-Martín J. Detección de resistencia inducible a clindamicina en aislados cutáneos de Staphylococcus spp. por métodos fenotípicos y genotípicos. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 2007; 25 (2): 77-81.

- Hamilton-Miller JM, Shah S. Patterns of phenotypic resistance the macrolide-lincosamide-ketolide-streptogramin group antibiotics in staphylococci. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2000: 46 (6): 941-949.

- Fiebelkorn KR, Crawford SA, McElmeel ML, Jorgensen JH. Practical disk diffusion method for detection of inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2003; 41 (10): 4740-4744.

- Nakajima Y. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to macrolide antibiotics. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy: Official Journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy 1999; 5 (2): 61-74.