Abstract

Background: In many Low and middle income countries HIV and cervical cancer have always been interlinked, as HIV patients are more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer at a young age. The policy in Kenya is to screen all HIV positive women for cancer of the cervix.

Objective: This study aimed to explore the increase in incidences of advanced cervical cancer in young HIV Negative women, as compared to HIV Positive, presenting at the hospital. Methodology: A review of hospital records of all patients aged 13-35 years presenting with Cancer of the Cervix regardless of HIV status at time of diagnosis in the period 2012 - 2019 of the study and purposive active recruitment of same age set in the 2020-2021period.

Findings: After the introduction of routine voluntary early screening of HIV +VE women, there was an increase of 15.91% of routine early screening of cancer of the cervix in the young HIV +VE patients as compared to their HIV –VE counterparts, from 3.85% to 19.76% in the 2012-2019 and 2020-2021 study periods.

Conclusion: Our conclusion is that apparently due to the early routine cancer of the cervix screening of young HIV positive women, cases are being diagnosed very early, in the pre-cancer and early stages, leading to early treatment and remission, in turn leading to the increased contribution of young HIV negative women with advanced cancer of the cervix.

Keywords

Policy; Routine; Young-women; HIV; Hospital Records; Western Kenya

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women globally, with an estimated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths in 2020 [1]. About 90% of the new cases and deaths worldwide in 2020 occurred in low and middle – income countries [1].

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the highest burden of cervical cancer in the world. Africa accounted for 21% of total cases and 26% of global deaths from cervical cancer in 2012 [1,2]. In Africa, Cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women in Eastern, Western, Middle, and Southern Africa and these women in Sub-Saharan Africa are disproportionately affected with cancer of the cervix, between 2% to 4% having a lifetime risk of the disease [1] In 2018, cervical cancer was the fourth most common cancer among women and the seventh most common cancer overall with 570,000 new cases and 311, 000 deaths reported, [2] 85% of whom were in low-middle-income countries, where vaccination, screening and treatment programs are limited [3] Eighty percent (80%) of the new cases occur in low and middle income countries, where it is the most common cancer in women, accounting for 13 % of all cancers in female patients [1,4 ] Western countries have experienced dramatic reductions in the incidence of and mortality from invasive cervical cancer, due to interventions that include vaccination against HPV and early diagnosis and treatment of patients with cervical cancer [5].

In Kenya, Cervical cancer contributes approximately 12% of all cancer cases diagnosed, and is the leading cause of all cancer deaths, with over 3,200 deaths reported in 2020 [1]. The uptake of screening is low (approximately 16% in 2015) [6] and only a quarter of 2,927 sampled health facilities offered screening in 2018, [6] despite the fact that Kenya has been implementing a national screening programme for more than a decade [7].

The HIV/AIDS epidemic led to Early Onset incidences of cervical cancer at a global level, with increasing incidence in women below 40 years of age, compared to the previous age - set of women in their 6th-7th decades of life developing cervical cancer, before the onset of HIV/AIDS [8,9 ]. In HIV-infected women, there is an increased risk of HPV infection and squamous intraepithelial lesions {SIL}, the precursor of cervical cancer [10 ,11].

Early onset cancers, defined as cancers in adults aged 18 to 49 years, are increasing in incidence, in a number of cancer sites in developed countries [12]. The incidence rate of earlyonset cancers increased by 20.5% from1993-2019 in Northern Ireland [12]. The impact of cancer treatment on fertility and fertility preservation treatments is an important consideration, bearing in mind that patients with early-onset cancers face unique supportive care needs and require holistic care [12]. An increased use of screening programmes has contributed to this phenomenon of early-onset cervical cancer to a certain extent (although the uptake in Kenya is still very low), a genuine increase in the incidence have emerged. Evidence suggests an aetiological role of risk factor exposures in early life and young adulthood [13]. Since the mid-20th century, substantial multigenerational changes in the exposome have occurred, including changes in diet, lifestyle, obesity, environment and the micro biome, all of which might interact with genomic and/or genetic susceptibilities [13]. This may reflect age-cohort effects and the emergence of more aggressive histologies with a shorter natural history, possibly the result of Human Papilloma Virus {HPV} infection acquired at a younger age or of increased screening/awareness resulting in earlier detection of cervical cancer [8,9].

Climate change is also affecting health and health patterns, which need to be studied, to evacuate and mitigate any impacts it may be having in early development of cancers globally.

We observed recently, that the number of Early Onset cancer of the cervix in HIV negative women of ages 13-35 years, diagnosed with advanced cancer of the cervix, has been increasing steadily at JOOTRH as from 2020 as compared to the previous period since inception of the Oncology Clinic in January 2012 to December 2019. This is opposed to the recent documented development of cervical cancer in HIV-negative women, which has been from the 4th to the 7th decade’s overtime, most frequently diagnosed in the U.S between the ages of 35 - 44, with the average age at diagnosis being 50 years old, more than 20% are diagnosed at 65 years of age, according to the American Cancer Society, updated 2023 [7 ].

The Early Onset cancer of the cervix has led to the young women having aggressive managements including hysterectomies depending on the stage of the disease. This has led to increased psychological complications which are attached to the consequences of the surgeries in women who had plans of having sizable families in the future. This has introduced a new dimension in the hospital management of these young women, some of whom are nulliparous.

In respect to the above, this study’s objective was to investigate the increase in incidences of Early Onset cancer of the cervix in HIV-VE women coming to the oncology clinic at the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital.

Materials and Methods

Study site

The study was conducted at the Oncology Clinic of the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital {JOOTRH}. Kisumu County, about 6 Kilometers from the Kisumu city business district (CBD), along the Kisumu-Kakamega road next to the Western region’s Blood Transfusion Centre. The Oncology Clinic is a separated from the administration block by a small fishpond and is next to the JOOTRH College’s Director’s office. The Clinic operates 8 hours per day from Monday to Friday and has a staff base made of 1 Gynaecology-Oncologist, 1 Medical-Oncologist, 1 Medical officer, 4 Nurses, 1 Nutritionist, 1 Pharmacist and 1 support staff.

Kisumu City of Kisumu County is the third-largest city in Kenya after the capital, Nairobi, and Mombasa [14 ]. It is the secondlargest city after Kampala in the Lake Victoria Basin. Located at the shores of the world’s second largest freshwater lake, Lake Victoria and at 1,131 m (3,711 ft.), the vibrant third largest city in Kenya, Kisumu City, boasts of a rich history of international trade, tropical climate, good transport network and a vibrant population majorly the Luo ethnic tribe of Kenya. The city has a population of slightly over 600, 000 [14 ]. The metro region, including Maseno and Ahero has a population of 1,155,574 people (560,942 males, 594,609 females) according to the 2019 Kenya Population and Housing census which was conducted by the Kenya national Bureau of Statistics [14 ]. Kisumu is the principal city of western Kenya and forms the commercial, industrial and transportation center majorly due to its water and rail connections. Formally the headquarters of the greater Nyanza Province, the town has grown to be the third largest city in Kenya after Nairobi and Mombasa and is now the headquarters of Kisumu County. The main industries in Kisumu are centered around processing of agricultural products, fishing, brewing and textile manufacturing industries. The Luo tribe is the main inhabitants of Kisumu County, but because it is made up of the city and rural areas around the metro zone, it is a melting pot of other tribes like the Luhya, Kisii, Kuria, Somali, Kikuyu, Kamba and others [14 ].

The JOOTRH also serves the neighbouring counties of Kakamega, Siaya, Kisii, Nyamira, HomaBay, Busia, Bungoma and Migori [14 ]. JOOTRH is a teaching and referral hospital, where many cancer cases such as gynaecological cancers are treated. It serves as the only oncology referral hospital in the county and for the counties of Siaya, HomaBay, Migori, Nyamira and Busia. Management of cervical cancer offered at this facility includes surgery and chemotherapy but has no radiotherapy unit. It offers also CT and MRI imaging and a well-equipped Pathology laboratory. The HIVClinic screens newly diagnosed patients for cancer of the cervix after two months of attendance treat pre-cancerous lesions immediately and refer the confirmed cancers to the Oncology Clinic.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

The study included all the files of patients with early onset cervical cancer of ages 13-35 years, who were both HIV- Negative and HIV - Positive at time of diagnosis and had histological diagnosis, in the period 2012 - 2019. We also purposively recruited all patients with above characteristics in the period of 2020 – 2021.

Sample

In this quantitative and qualitative study, in the 2012-2019 periods, patients’ files for all HIV positive and negative cervical cancer patients who were of the ages 13-35 years old were purposively selected. The samples consisted of HIV +VE and HIVVE patients with Early Onset cervical cancer, and were being treated at the oncology clinic of the JOOTRH, since the inception of the clinic in January 2012-2019 December. In the period of 2020-2021, participants were purposively selected using maximum variation sampling strategy, as they were diagnosed and registered in the Oncology clinic. The patients were drawn from different population categories of ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, place of residences, level of education and religion. A total sample size of 52 files was selected, in the period of 2012-2019 and a sample of 86 participants was recruited actively in the prospective period of 2020-2021.

Procedure and research design

This was a mixed-methods study design, including both quantitative and qualitative components. The quantitative components focused on age sets, HIV statuses, cervical cancer vaccination, screening, diagnosis, histology results, Figo Staging in the period of 2012-2019 and 2020-2021 data reviews and analysis, with data sources being the patient files in the former period while using clinical research forms and other source documents in the latter period. The qualitative component involved evaluating knowledge about cervical cancer, sourced through review of files and use of clinical research forms and semi-structured interviews in the former and latter periods respectively. The study was based on the JOOTRH’s Oncology Clinic services to patients with early onset cervical cancer in both periods, within the age set of 13-35 years old.

Study period

The review of files was done for the period of 8 years since the inception of the Oncology in January 2012 to December 2019 (2012-2019), and the period of active recruitment, collection of data with clinical research forms and other source documents was in the period of September 2020 to September 2021 (2020- 2021).

Measurement

Data was collected using structured document analysis forms and lists in the period of 2012-2019, while clinical research forms and semi-structured interviews were used for data collection in the period of 2020-2021. The study specifically sought to determine the incidences of early onset cervical cancer cases, HIV-status, the patients’ demographics, knowledge of cancer, vaccinated against HPV, screening, stage of disease and histological results of the cancer tissues.

The primary outcome variable was the incidences of Early Onset Cancer of the cervix in both HIV Positive and Negative women of ages 13-35 years old. This variable was measured through all the reviewed files in the period 2012 - 2019 and of the actively recruited patients in the period 2020-2021.

The quantitative data were analyzed using Epi InfoTM 7.0 (US CDC, Atlanta, GA). The qualitative data was thematically tabulated while the quantitative data was summarized in trend series (bar charts and line graphs).

Ethical considerations

All the documents analyzed and patients recruited in this study, were accessed after getting an approval from the JOOTRH’s Ethical Review Committee (I.E.R.C) and express informed consent from the recruited patients. There was no patient who was coerced into joining the study and those who declined were not denied the standard of care for their ailment.

The approval for the review of the hospital records for the period 2012-2019 and active recruitment of patients for the 2020-2021 period, included statements about the rights of the subjects, in terms of their information collected, confidentiality and the publication of this report and any other accompanying information (Tables 1-5).

Table 1. Cancer of Cervix Table in the Period 2012 -2019 for HIV +Ve Cohort

Characteristics |

n = 22 |

|

| n / median |

% / range |

| Age, years |

23 |

13-35 |

| Residence |

|

|

| Urban |

10 |

45.50% |

| Rural |

12 |

54.50% |

| Vaccinated against H.P.V |

|

|

| Yes |

0 |

0% |

| No |

22 |

100% |

| Screened Voluntarily Prior to Symptoms |

|

|

| Yes |

7 |

31.80% |

| No |

15 |

68.20% |

| HIV Status |

|

|

| Negative |

22 |

100% |

| Positive |

0 |

0% |

| On HAART |

|

|

| Yes |

0 |

0% |

| No |

22 |

100% |

| FIGO 2020/2021 stage |

|

|

| IIA2 |

2 |

9.10% |

| IIB |

5 |

22.70% |

| IIIB |

5 |

22.70% |

| IIIC1 |

4 |

18.20% |

| IIIC2 |

5 |

22.70% |

| IVB |

|

|

| Tumour size, mm |

62 |

> 40 |

| Histology |

|

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

16 |

72.70% |

| Adenocarcinoma |

2 |

9.10% |

| Adeno - squamous cell carcinoma |

4 |

18.20% |

| Small Cell Neuro-Endocrine carcinoma |

0 |

0% |

| Type of imaging |

|

|

| CT |

22 |

100% |

| Patient-based nodal status on CT |

|

|

| Negative |

10 |

45.50% |

| Inconclusive |

3 |

13.60% |

| Positive |

9 |

40.90% |

| Region with positive nodal status on imaging b |

|

|

| Pelvic |

9 |

40.90% |

| Common iliac |

2 |

9.10% |

| Para-aortic |

5 |

22.70% |

| Patient-based nodal status on pathology |

|

|

| Negative |

13 |

59% |

| Positive |

9 |

40.90% |

| Unknown |

0 |

0% |

| Nodal examination |

|

|

| Absent |

3 |

13.60% |

| Lymphadenectomy |

4 |

18.20% |

| Nodal debulking |

0 |

0% |

| Biopsy/fine-needle aspiration |

22 |

100% |

| Sentinel node biopsy only |

0 |

0% |

Table 2. Cancer of Cervix Table in the Period 2012 -2019 for HIV-Ve Cohort

| Characteristics |

n=17 |

|

| n / median |

% / range |

| Age, years |

31 |

13-35 |

| Residence |

|

|

| Urban |

14 |

82.40% |

| Rural |

3 |

17.60% |

| Vaccinated against H.P.V |

|

|

| Yes |

0 |

0% |

| No |

17 |

100% |

| Screened Voluntarily Prior to Symptoms |

|

|

| Yes |

6 |

35.30% |

| No |

11 |

64.70% |

| HIV Status |

|

|

| Negative |

0 |

0% |

| Positive |

17 |

100% |

| On HAART |

|

|

| Yes |

17 |

100% |

| No |

0 |

0% |

| FIGO 2020/2021 stage |

|

|

| IIA2 |

9 |

52.90% |

| IIB |

3 |

17.60% |

| IIIB |

3 |

17.60% |

| IIIC1 |

1 |

5.90% |

| IIIC2 |

1 |

5.90% |

| IVB |

0 |

0% |

| Tumour size, mm |

75mm |

>40mm |

| Histology |

|

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

13 |

76.40% |

| Adenocarcinoma |

1 |

5.90% |

| Adeno - squamous cell carcinoma |

3 |

17.60% |

| Small Cell Neuro-Endocrine carcinoma |

0 |

0% |

| Type of imaging |

|

|

| CT |

17 |

100% |

| Patient-based nodal status on CT |

|

|

| Negative |

120 |

70.60% |

| Inconclusive |

30 |

17.60% |

| Positive |

2 |

11.80% |

| Region with positive nodal status on imaging b |

|

|

| Pelvic |

2 |

11.80% |

| Common iliac |

1 |

5.90% |

| Para-aortic |

1 |

5.90% |

| Patient-based nodal status on pathology |

|

|

| Negative |

15 |

88.20% |

| Positive |

2 |

11.80% |

| Unknown |

0 |

0% |

| Nodal examination |

|

|

| Absent |

5 |

29.40% |

| Lymphadenectomy |

2 |

11.80% |

| Nodal debulking |

0 |

0% |

| Biopsy/fine-needle aspiration |

17 |

100% |

| Sentinel node biopsy only |

0 |

0% |

Table 3. Cancer of Cervix Table in the Period 2020 -2021 for HIV +Ve Cohort

| Characteristics |

n=49 |

|

| n / median |

% / range |

| Age, years |

23 |

13-35 |

| Residence |

|

|

| Urban |

21 |

42.90% |

| Rural |

28 |

57.10% |

| Vaccinated against H.P.V |

|

|

| Yes |

0 |

0% |

| No |

49 |

100% |

| Screened Voluntarily Prior to Symptoms |

|

|

| Yes |

10 |

20.40% |

| No |

39 |

79.60% |

| HIV Status |

|

|

| Negative |

49 |

100% |

| Positive |

0 |

0% |

| On HAART |

|

|

| Yes |

0 |

0% |

| No |

49 |

100% |

| FIGO 2020/2021 stage |

|

|

| IIA2 |

4 |

8.20% |

| IIB |

18 |

36.70% |

| IIIB |

10 |

20.40% |

| IIIC1 |

6 |

12.20% |

| IIIC2 |

9 |

18.40% |

| IVB |

|

|

| Tumour size, mm |

71 |

>40 |

| Histology |

|

|

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

30 |

61.20% |

| Adenocarcinoma |

5 |

10.20% |

| Adeno - squamous cell carcinoma |

10 |

20.40% |

| Small Cell Neuro-Endocrine carcinoma |

4 |

8.20% |

| Type of imaging |

|

|

| CT |

49 |

100% |

| Patient-based nodal status on CT |

|

|

| Negative |

30 |

61.20% |

| Inconclusive |

4 |

8.20% |

| Positive |

15 |

30.60% |

| Region with positive nodal status on imaging b |

|

|

| Pelvic |

15 |

30.60% |

| Common iliac |

4 |

8.20% |

| Para-aortic |

9 |

18.40% |

| Patient-based nodal status on pathology |

|

|

| Negative |

34 |

69.40% |

| Positive |

15 |

30.60% |

| Unknown |

0 |

0% |

| Nodal examination |

|

|

| Absent |

10 |

20.40% |

| Lymphadenectomy |

10 |

20.40% |

| Nodal debulking |

0 |

0% |

| Biopsy/fine-needle aspiration |

49 |

100% |

| Sentinel node biopsy only |

0 |

0% |

Table 4. Cancer of Cervix Table in the Period 2020 -2021 for HIV-Ve Cohort

| Age Group |

2012-2019 |

2020-2021 |

| Oct-14 |

1 |

0 |

| 15-19 |

0 |

6 |

| 20-25 |

15 |

31 |

| 26-30 |

12 |

14 |

| 31-35 |

10 |

15 |

| 36-40 |

2 |

12 |

| 41-45 |

5 |

5 |

| 45&above |

7 |

3 |

| TOTAL |

52 |

86 |

| P-VLUE |

0.012 |

0.017 |

| MEAN |

6.5 |

10.75 |

| CI (MEAN) |

1.921, 11.079 |

2.562, 18.938 |

| DF |

7 |

7 |

Table 5. Sample

Analysis of the HIV +VE women aged 13-35 years old, routinely screened early before Policy in the 2012-2019 study period, as compared to those screened early routinely after the Policy introduction in the 2020-2021 study period

2012-2019 period

Total Patients (HIV + VE and HIV -VE) = 52

HIV +VE (13-35 years old) = 16

Hence Percentage = 16/52= 0.3076/8 years (2012-2019) x 100 = 3.85% who had early routine voluntary screening

2020 – 2021 period

Total Patients (HIV +VE and HIV –VE) = 86

HIV +VE (13-35 years old) = 17

Hence Percentage = 17/86= 0.1976/1 year (2020 -2021) x 100 = 19.76%

Interpretation

There was a significant and major increase in the uptake of early voluntary routine screening of the cervix in the period of 2020-2021 of HIV +VE women aged 13-35 after introduction of the voluntary routine early screening, making up to 19.76% as compared to the earlier period of 2012 – 2019, that made up only 3.85%% annually, before the introduction of the policy (Table 6).

| |

Urban |

Rural |

Total |

| HIV+ |

22 |

25 |

47 |

| HIV- |

37 |

55 |

92 |

| Total |

59 |

80 |

139 |

Table 6. Analysis of predisposition of HIV+ women in rural to cervical cancer

Odds Ration=([HIV]^+×RURAL)/([HIV]^-×URBAN)=(22×55)/

(37×25)=1.3

100(1.3-1) %=30%

[X_Cr]^2>[X^2] c

1.3>0.004

The results are statistically significant

Interpretation

A HIV+ woman living in rural area is 30% more likely to get cervical cancer compared to HIV- in urban area.

Odds Ratio= ([HIV]^-×RURAL)/([HIV]^+×URBAN)=(37×25)/ (22×55)=0.76

100(1-0.76) %=24%

[X_Cr] ^2>[X^2]c

0.76>0.004

The result is statistically significant

Interpretation

A HIV-woman living in rural area is 24% less likely to get cervical cancer compared to HIV+ woman living in urban area.

HIV+ or HIV- woman in rural area has higher chances of getting cervical cancer compared to their counterparts in urban areas (Table 7).

| |

Urban |

Rural |

Total |

| 2012-2019 |

19 |

33 |

52 |

| 2020-2021 |

40 |

47 |

87 |

| Total |

57 |

80 |

139 |

Table 7. The likelihood of getting cervical cancer in 2012-2019 and 2020-2021 periods

Odd Ratio=(2020-2021 Period×Rural)/(2012-2019

Period×Urban)=(19×47)/(40×33)=0.68

100(1-0.68) %=32%

[X_Cr]^2>[X^2]c

0.68>0.004

The result is statistically significant

Interpretation

A woman, whether in town or rural area was 32% less likely to get cervical cancer between 2012 and 2019 compared to 2020-2021 period.

Discussions

The study showed increasing incidences of Early Onset cancer of the cervix in HIV-VE young women at the JOOTRH. This in agreement to the recent published data that has seen the changing incidences of cervical cancer at a global level, with increasing incidence in women below 40 years of age [15,16], and a study that reported that eighty percent (80%) of the new cases occur in developing countries, where it is the most common cancer in women, accounting for 13% of all female cancers [17]. This is also in agreement with the findings of a study that stated that in 2020 estimates, cancer of the cervix incidences increased in some countries in Eastern Africa and Eastern Europe [18]. The Global incidence of early-onset cancer increased by 79.1% and the number or early-onset cancer deaths increased by 27.7% between 1990 and 2019 [19]. The results indicated that in lowmiddle and low Socio-Demographic Index regions, early-onset cancers had a significantly higher impact on women than on men in terms of both mortality and disease burden [19].

This is in contrast to other previous studies that reported a link between young age at diagnosis of cancer of the cervix with HIV/ AIDS, where an association between HIV infection and cervical cancer was noted especially in women aged less than 40 years of age, which was consistent with the published observations [20], although in Romania, which is a leading country in Europe had an incidence of 28.6/100,000 of cervical cancer cases, even though it is not an HIV endemic country, indicating that the increased incidence had not been contributed to by the HIV/ AIDS pandemic [21]. A separate study in Kenya, stated that there was no significant change in either age at presentation or severity of cervical cancer between HIV +VE and HIV-VE patients at the Kenyatta National Hospital, although, of the 118 patients who were tested for HIV, 36 (31%) were sero-positive, while the rest were sero-negative and these women according to the study, were 5 years younger at presentation than HIV-VE women [22]. In yet another study in Romania, it reported that HPV prevalence, after age adjustment, was at 51.2% in HIV +VE versus 63.2% in HIV-VE women aged under 25 years of age and 22.2% in HIV+VE versus 47.2% in HIV-VE women aged 25-34 years of age in Romania [23], this showed that overall, HPV prevalence was higher in the HIV-VE women than HIV+VE women, and in the same vein, the HPV was more prevalent in younger patients who are HIV-VE as compared to those who are of the same age group but are HIV+VE in Romania [23]. There is yet another study that agrees with this study’s finding above, it reported that, early starters have more years to experiment with sex, tend to engage in sexual activity faster when in a new relationship, and accumulate more sexual partners and unprotected encounters overtime, hence exposure to HPV very early [24].

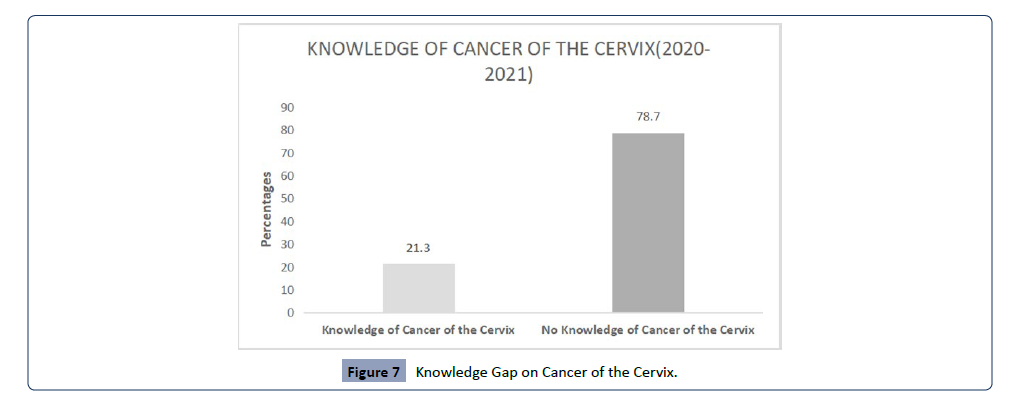

The study also analyzed the knowledge gap in Cancer of the Cervix, and the findings was that 68 participants (79%) had no knowledge on this cancer, as compared to 18 (21%) who had some knowledge, with a preponderance of those who had no knowledge being from the rural areas. This is in agreement with a study which reported that, the awareness of risk factors for Ca. Cervix, also varies from country to country, with huge knowledge gaps between the developed and developing countries, where, nearly all female students (98%) in Krakow or its vicinity in Poland-Europe have heard of Cervical Cancer, with 89.4% being aware of the risk of death associated with Ca. Cervix, and most (91.5%) are aware of cytological screening, and 86.5% think that they should have it done in the future [25]. The other study that supports our finding stated that, in Nepal, South Asia, which is a developing country, it was reported that more than 50% of high school students were not familiar with the knowledge, which was similar to a Japanese survey on the same topic [26]. The lack of knowledge, hence less perceived susceptibility were major obstacles among mothers, limiting cervical cancer screening to 15% and yet Ca. Cervix is a major cause of death in Nepal, resulting in 18.4% of all deaths, despite the fact that the numbers may be under-reported due to a lack of a cancer registry [27]. An African study that is also in agreement with our finding, reported that the Ca. Cervix risk factor knowledge in Zimbabwe, of more than or equal to 13 out of 26, was reported to be at 13% of high school students and 14% of University students with a broad range of misconceptions about cervical cancer risk factors in both males and females [28]. A Kenyan study that seems to be in agreement to our finding, states that, in Kenya, although 91% of the surveyed women had heard of cancer, only 29% had heard of cervical cancer and some of its risk factors, fewer women (6%) had ever been screened for Ca. Cervix and cited barriers such as fear, time, and lacking knowledge about cervical cancer [29]. The Kisumu study, whose publication also supports our finding, reports that, just about 29% of the women surveyed had ever heard of cancer of the cervix, and only 6% had been screened previously [30].

The study found out that most patients presented to the hospital in advanced stages of cancer of the cervix, and 39 (64%) were diagnosed at FIGO Stages III and IV, while just 22 (36%) were diagnosed at Stages II and III in the prospective study, mostly due to presenting themselves for the voluntary screening programme.

In yet another finding, voluntary screening of the Ca. Cervix for young HIV-VE women was still very low, even though the services are free and offered in public health institutions. In the Prospective study, just 12 (20%) had been screened, while 49 (80%) had not been screened at all, of the total 61 patients. This is supported by a published study, that reported that lack of knowledge and less perceived susceptibility were major obstacles among mothers, limiting cervical screening to 15% and yet Cancer of the Cervix is a major cause of death in Nepal, resulting in 18.4% of all deaths, despite the fact that the numbers may be under-reported due to a lack of a cancer registry [27]. A second study in Kenya that agrees with this finding, states that, few women (6%) had ever been screened for cervical cancer and cited barriers such as fear, time, and lacking knowledge about cervical cancer [30]. A study in Kisumu, reported that just about the same 6%, had previously been screened even once for Ca. Cervix voluntarily

The first unexpected finding in this study, was the overall low uptake of screening for cancer of the cervix amongst the participants at the JOOTRH, where only 20% of the patients had been screened prior in the period of 2021-2022. This may have happened due to the finding of lack of knowledge described above, with other agreeing past studies or the above barriers for not going for screening in the finding above about screening, including fear and lack of time. This unexpected finding may be a factor in explaining the main objective and question, on the increasing incidences of Early Onset cancer of the cervix in HIV-VE young women at JOOTRH. This is because with no or minimal screening, most patients develop neoplasia silently and unknowingly, and then come to the hospital late with symptoms of advanced cancer of the cervix [FIGO STAGES III and IV].

The second unexpected finding was the lack of knowledge on the availability of HPV vaccines to prevent the development of Cancer of the Cervix. Amongst the 21% who had some knowledge about Ca. Cervix, none of them had knowledge of availability of the HPV vaccines, and that the government had introduced the vaccine into its routine immunization schedule in October of 2019, and is now offered for both girls and boys of ages 9-26 years, with the optimal age of administration being 9-14 years. In the 2020-2021 period HIV-VE arm of the study, there were six (6) teenagers who had not heard anything about the HPV vaccine and yet the Primary and Secondary schools were to be centers for creation of awareness and mobilization for the HPV Vaccine. This finding is linked to the lack of knowledge, which is contributing to lack of mitigation on the risk factors, hence may be leading to the study objective/question of the increase in the incidences of early onset cancer of the cervix in HIV-VE young women at the JOOTRH Oncology Clinic.

This study did not involve laboratory investigations for HPV identification and types, hence it needs a follow up research that will involve taking cervical smears to the laboratory to investigate the presence of HPV in the cervix of the respective patients, identify the various types of the HPV, ascertain if there are particular patients who have a combination or mixed presence of two or more HPV.

This study showed increasing incidences of early onset of cancer of the cervix in of HIV-VE young women at the JOOTRH. This study was important for the future trajectory of Ca. Cervix and its control among young women in the country.

In our study, our overall finding was that the Policy of early routine screening and treatment of Ca. Cervix in the HIV+VE patients, was reducing the prevalence of the cancer in young women who are HIV+VE, this was evident with 5 participants (20%) being diagnosed in the one year 2020-2021 period of the study, after the Policy of early routine screening had been implemented, as compared to 20 participants (80%) who had been diagnosed in the 8 years 2012-2019 study period before introduction of the policy. This is in agreement with the revised CDC AIDS case definition since 1993, which included the development of cervical cancer in an HIV +VE patient as a sufficient criterion for AIDS, even in the absence of an opportunistic infection; this led to the active early mandatory and routine screening of Ca. Cervix in all newly diagnosed HIV infected persons, for early diagnosis and treatment [31].

This is in contradiction to the revised CDC AIDS case definition and treatment for AIDS, which has included the development of cervical cancer in an HIV infected person as sufficient criterion for AIDS, even in the absence of an opportunistic infection, hence the active mandatory and routine screening for Ca. Cervix, to enable early diagnosis and treatment as part of HIV/AIDS management,leading to higher percentages of HIV+VE patients being screened [31] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Study Periods 2012-2019 and 2020-2021..

• Although the number of observations are different (2020-2021= 86, 2012-2019 = 52), there is more prevalence of cervical cancer among young (<35yrs old) women.

• Although 2012-2019 periods are longer than prospective, more cases were reported in the latter period of 2020-2021. The incidence rate of early onset cancer of the cervix is increasing with time.

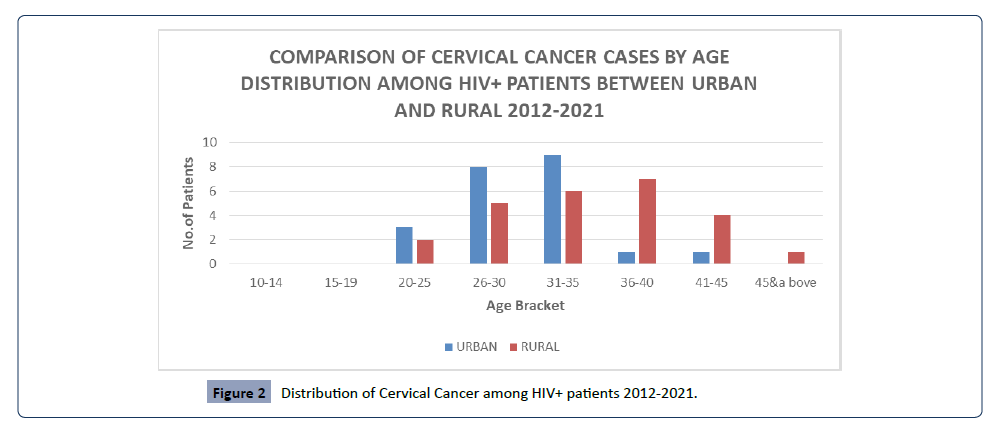

• Women in the 20-25 years age bracket exhibit more cases compared to other child-bearing age groups, although with the longer period of eight years (2012-2019) in the , as compared to the shorter period of one year (2020-2021) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Cervical Cancer among HIV+ patients 2012-2021 Both 2020- 2021 and 2012-2019 Study periods.

1. Over the period, there is more prevalence in the rural areas.

2. Young women in urban areas experience more incidences compared to similar age group in rural areas, although the first period of study is longer at 8 years (2012-2019), as compared to the shorter period of one year (2020-2021).

3. Older women in rural areas present more cervical cancer cases compared to those in urban areas.

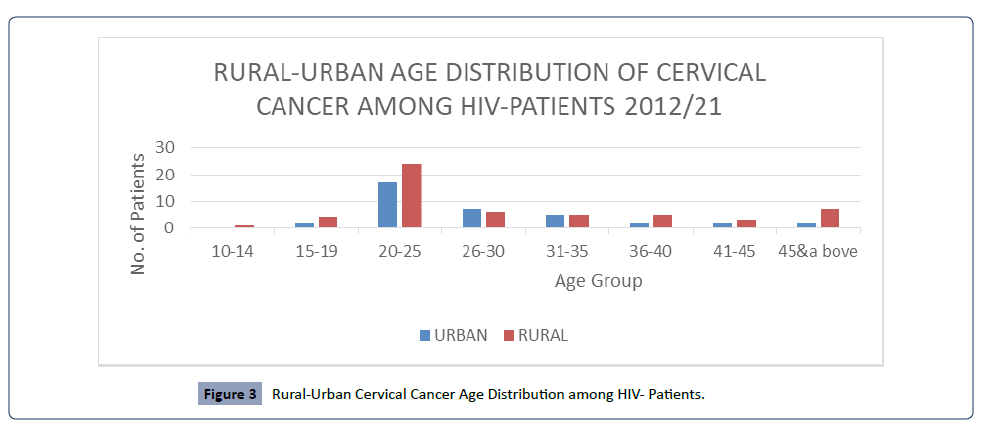

4. There was a higher percentage of rural residing HIV negative (HIV -VE) young women (<35 years of age), diagnosed with cancer of the cervix in the 2020-2021 period of study, at 57% , compared with 43% residing in the urban centers (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Rural-Urban Cervical Cancer Age Distribution among HIV- Patients..

• It is surprisingly 1 patient below 14years in rural area presented with cervical cancer, in the 2012-2019 study periods.

• 4 patients aged between 15-19 in rural presented cervical cancer cases, in the 2020-2021 period of study.

• The prevalent age bracket is 20-25 years old and biased towards rural patients, even though the first period of review is longer at 8 years (2012-2019), while the second period of study is shorter at one year (2020-2021).

• There was a higher percentage of rural residing HIV negative (HIV -VE) young women (<35 years of age), diagnosed with cancer of the cervix in the 2020-2021 period of study, at 57% , compared with 43% residing in the urban centers.

• The first period of study, although is a longer duration of eight years, between 2012-2019, the young (<35 years old) HIV negative (HIV -VE) women diagnosed at FIGO Stages III and IV, are at 80% for those residents of the rural settings, as compared to 20% of those who reside in the urban centers.

• There is a preponderance of young (<35 years of age) HIV negative (HIV -VE) women being diagnosed at advanced stages (FIGO Stages III and IV) of cancer of the cervix at 74% residing in the rural areas, as compared to 26% urban dwellers, all in a period of one year 2020-2021 of study (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Rural-Urban Age Distribution 2012-2019 Period..

• Although 2012-2019 period is long, only one patient below 20 years old (13yrs) presented with cervical cancer, and it is in rural area. No urban case featured in the below 20 years during that period.

• Most incidences in the period was in age group 20-25 mostly in rural areas, but during the longer period of eight years (2012-2019) of study, from year of inception of oncology clinic to end of 2019, the year of review.

• The first period of study, although is a longer duration of eight years, between 2012-2019, the young (<35 years old) HIV negative (HIV -VE) women diagnosed at FIGO Stages III and IV, are at 80% for those residents of the rural settings, as compared to 20% of those who reside in the urban centers (Figure 5).

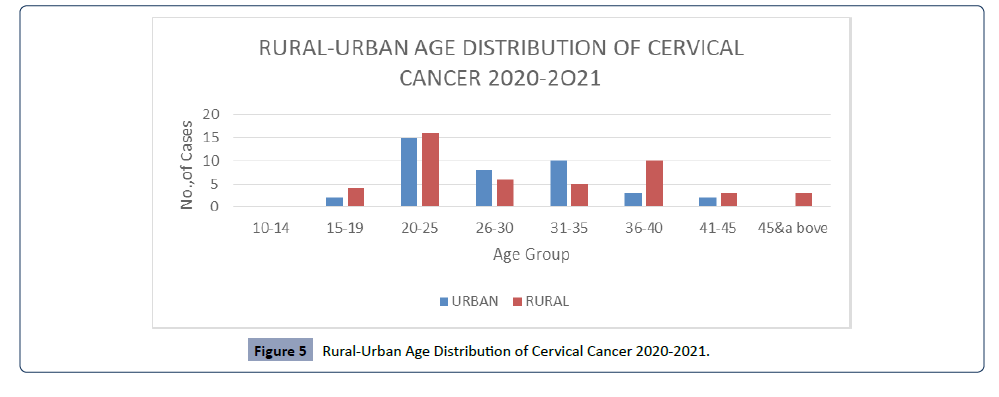

Figure 5: Rural-Urban Age Distribution of Cervical Cancer 2020-2021.

• During this period, there were more cervical cancer cases than the previous one.

• There are more cervical cancer cases in very young women in this one year 2020-2021 study periods, than in the longer 8 year 2012-2019 study periods, i.e., patients below 19 years than in the previous period.

• There are more cases in rural than urban.

• There most prevalent age group is 20-25 biased in favour of rural residents.

• There was a higher percentage of rural residing HIV negative (HIV -VE) young women (<35 years of age), diagnosed with cancer of the cervix in the 2020-2021study period, at 57%, compared with 43% residing in the urban centers.

• There is a preponderance of young (<35 years of age) HIV negative (HIV -VE) women being diagnosed at advanced stages (FIGO Stages III and IV) of cancer of the cervix at 74% residing in the rural areas, as compared to 26% urban dwellers, all in a period of one year of study, 2020-2021 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: FIGO Classification of Cervical Cancer Presentation.

• The 2012-2019 study period, although is a longer duration of eight years period , the young (<35 years old) HIV negative (HIV -VE) women diagnosed at FIGO Stages III and IV, are at 80% for those residents of the rural settings, as compared to 20% of those who reside in the urban centers.

• There is a preponderance of young (<35 years of age) HIV negative (HIV -VE) women being diagnosed at advanced stages (FIGO Stages III and IV) of cancer of the cervix at 74% residing in the rural areas, as compared to 26% urban dwellers, all in a period of one year of study 2020-2021.

• The FIGO Staging of Cancer of the cervix had a P-value of 0.01906, being statistically significant, meaning diagnosis at advanced stages of III and IV for the young HIV -VE has increased compared to the HIV +VE in this period (Figure 7).

Figure 7:Knowledge Gap on Cancer of the Cervix.

A total of 21% (18 patients) of patients had some prior knowledge of cancer of the cervix, as compared to 79% (68 patients) of patients, who had no idea at all on cancer of the cervix as a disease.

The patients who had some knowledge on cancer of the cervix were mostly the ones who had self-referrals, as compared to those who had no knowledge at all, and thought they had normal vaginal discharge and bleeding post coitus, hence were referred in advanced stages to the oncology clinic.

In the 21% who had some prior knowledge of cancer of the cervix, 22% (4 women) from the rural areas had some knowledge as compared to 78% (14 women) urban residents who had some knowledge.

Amongst the 79% who had no knowledge of cancer of the cervix, 81% (55 women) were residents of the rural communities; whereas 19% (13) were urban dwellers.

Screening of cancer of the cervix

In the first period of study, the voluntary screening programme had 23% HIV -VE patients screened while 77% had not been screened prior in the 2012-2019 period, when the diagnosis of cancer was confirmed. Amongst this 23% group that had been screened, 86% were urban residents, as compared to 14% of rural residents who had been screened in the eight years period of 2012-2019. Amongst the 77% of patients who had never been screened prior to diagnosis of cancer in the eight year study period 2012-2019, 71% were rural residents as compared to 29% who were urban dwellers.

The HIV +VE in the first period of review, 2012-2019, before the policy for routine early screening of cervical cancer in HIV +VE women had been introduced in the HIV Clinics, 10% who had come for the voluntary screening prior before diagnosis of cancer in the eight year period of 2012-2019, while 90% had never been screened before cancer diagnosis in the same eight year period2012-2019. In this 10% group who had come for voluntary screening, all of them, 100%, were rural residents, none of the urban residents had used the voluntary screening programme before diagnosis of cancer of the cervix. In the 90% group who had never been screened before cancer diagnosis in the eight year period of 2012-2019, 68% were from the rural areas, where as 32% were urban residents.

In the second study period, the voluntary screening programme had 20% HIV -VE patients screened while 80% had not been screened prior in the one year period of 2020-2021, when the diagnosis of cancer was confirmed. Amongst this 20% group that had been screened, 83% were urban residents, as compared to 17% of rural residents who had been screened in the one year period of 2020-2021. In the 80% group that had never been screened prior to diagnosis of cancer, 71% were from the rural areas, where as 29% were urban residents.

The HIV +VE in the second study period, when the policy for routine early screening of cervical cancer in HIV +VE women had been introduced in the HIV Clinics, had 28% who had come for the voluntary screening prior before diagnosis of cancer in the one year period 2020-2021, while 72% had never been screened before cancer diagnosis in the same one year study period 2020- 2021. In this 28% group who had come for voluntary screening, all of them 100%, were urban residents, none of the rural residents had accessed the voluntary screening before diagnosis of cancer of the cervix. Of the 72% who had not been screened prior to diagnosis in the one year period of study, 2020-2021, all of them, 100% were rural residents.

The above findings show a clear increase of 18% of routine early screening of cancer of the cervix in the young HIV +VE patients as compared to their HIV –VE counterparts, from 10% in the 2012-2019 study period to 28% in the 2020-2021 study period, of routine early screening in the young HIV +VE patients as compared to their HIV –VE counterparts.

Conclusion

The study concludes that, routine early screening and treatment of Ca. Cervix in the HIV+VE patients, was reducing the incidences of the cancer in young women who are HIV+VE, significantly leading to an increase of incidences of advanced cancer of the cervix in young HIV negative women at the Oncology Clinic of JOOTRH in Western Kenya. This study also analyzed the burden of cancer of the cervix (Ca. Cervix) between young women who reside in the rural areas versus those in the urban areas, and the finding was that the young rural women were bearing the burden of Ca. Cervix more than their urban counterparts. The study also analyzed the knowledge gap in Cancer of the Cervix, and the findings was that 79% had no knowledge on this cancer, as compared to 21% who had some knowledge, with a preponderance of those who had no knowledge being from the rural areas. The study found out that most patients presented to the hospital in advanced stages of cancer of the cervix, and 64% were diagnosed at FIGO Stages III and IV, while just 36% were diagnosed at Stages II and III in the prospective study, mostly due to presenting themselves for the voluntary screening programme. In yet another finding, voluntary screening of the Ca. Cervix for young HIV-VE women was still very low, even though the services are free and offered in public health institutions. In the Prospective study, just 20% had been screened, while 80% had not been screened at all.

The first unexpected finding in this study was the higher percentage or young rural HIV-VE women with CA. Cervix who had never been able to get screened voluntarily even once, and yet the services are free and being offered in public health centers. This is seen in the findings of the Prospective HIV-VE study arm, where of the 20% patients who had been screened prior, just 17% were rural dwellers, yet 83% were from the urban centers. On the contrary, of the 80% who had never been screened even once prior in this Prospective HIV-VE arm, 71% were residents of rural areas, while just 29% of urban residents had not been screened.

The second unexpected finding was the lack of knowledge on the availability of HPV vaccines to prevent the development of Cancer of the Cervix. Amongst the 21% who had some knowledge about Ca. Cervix, none of them had knowledge of availability of the HPV vaccines, and that the government had introduced the vaccine into its routine immunization schedule in October of 2019. In the Prospective HIV-VE arm of the study, there were six (6) teenagers who had not heard anything about the HPV vaccine and yet the Primary and Secondary schools were to be centers for creation of awareness and mobilization for the ten (10) year olds, who were to first get the immunization against HPV.

Recommendations

The study recommends that, the policy of routine early screening of cancer of the cervix in all HIV +VE women should continue and spread all over the country, even to the remotest rural areas to benefit women in those regions. This routine early screening should be done also to the young HIV-VE women in the entire country. The study recommends that, this upsurge of early onset cancer of the cervix cases in young HIV-VE patients, need to be researched comprehensively, in a multi-center, multi-national prospective study, and with a larger sample size, to identify the contributing factors and initiate interventions to curb this trend. If these factors will not be studied, identified and mitigated, the incidences of young HIV-Negative women with early onset cancer of the cervix will continue to increase and we will continue having morbidities and mortalities at this young reproductive and productive age group.

This study did not involve laboratory investigations of HPV types, hence it needs a follow up research that will involve taking cervical smears to the laboratory to investigate the presence of HPV in the cervix of the respective patients, identify the various types of the HPV, ascertain if there are particular patients who have a combination or mixed presence of two or more HPV types. The mitigation also should be done using the WHO’s (90- 70-90 goals) Global strategy towards the elimination of cervical cancer, and any other novel methods, depending on what the study establishes as the contributing factors to the young age at diagnosis of advanced cancer of the cervix in this region. The W.H.O goals mean, all countries should as a Primary prevention, achieve, 90% of girls fully vaccinated with HPV vaccine by 15 years of age, as a Secondary prevention achieve 70% of women screened using a high-performance test, by 35 and 45 [19] years of age and as a Tertiary prevention achieve 90% of women identified with cervical disease are treated [18]; split further into 90% of women with pre-cancer lesions treated and 90% of women with invasive cancer managed. We also intend, as a core Primary prevention strategy, to advocate for inclusion of cancer of the cervix teaching as a topic in the science, social studies and biology curriculum of primary and high schools, to equip pupils and students with the knowledge. For the goals to be achieved, we will impress on the county governments and countries to invest more on the above strategies for the eradication of cancer and share with them the long term cost-benefits/savings of their investments.

Source of Funding

The PhD candidate used his funds, and was helped by the personnel at the hospital, together with volunteering students and the investigators availed their expertise locally to conduct the study. We used the local hospital paper records in the cabinets of the oncology department and the records office. Uzima University School of Medicine supported the study by availing the volunteering students.