Keywords

Menstrual; Hygiene; Blood borne infections

Introduction

Menstruation is a cyclic event that occurs during the reproductive phase of a woman’s life. It involves the discharge of mainly blood, mucous and endometrial shreds from the lining of the uterus. According to Lynch the nature and amount of monthly menstrual flow vary from woman to woman but on average, menstrual blood can flow up to the amount of 30 ml per day and the average flow can take four days. Lynch went on to say that, menstruation has been managed in many ways across time and culture - with some women having to let their menses flow freely and others adopted the tradition of making internal and external menstrual wear from available products.

The word “sanitary” is often used to indicate that menstrual wear products are bleached although not sterile. Sanitary napkins are in greater use in places where a lot of girls stay together like boarding schools and tertiary institutions. This aggregation of girls compounds the challenge for the management and disposal of menstrual waste products which is the focus of this study. Swaziland as a country has a number of boarding public secondary schools that host girls who by dictates of nature have to produce sanitary menstrual wastes especially blooded sanitary napkins that must be properly disposed of. Human body fluids that are visibly contaminated with blood and other body fluids generated from circumstances where there is potential for the presence of infectious agents are classified as clinical waste. If not properly disposed of, the infectious agents from these clinical wastes can increase the risk of transmission of blood borne diseases such as the Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Hepatitis B [1]. Since menstruation is a natural event, a key priority for women and girls is to have the necessary knowledge, facilities and cultural environment to manage it hygienically and with dignity. However, the importance of menstrual hygiene management is mostly neglected by development practitioners within the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) [2] and other related sectors such as reproductive health practitioners [3-5].

It is the observation of the researchers that there is improper disposal of sanitary napkins within the public boarding schools in the country as they observed in a few such schools that sanitary napkins are dropped into specific bins in the girls’ toilets and periodically collected by cleaners for open burning within the schools’ premises or disposed of in the general waste bins within the school premises. In addition, menstrual hygiene management is absent in programmes for community water and sanitation, school sanitation as well as hygiene promotion. There is still inadequate incorporation of menstrual hygiene into infrastructural design for toilets and environmental waste disposal or policies, training manuals or guidelines, with those for health workers, engineers and gender mainstreaming. Such practices are in contradiction with the Swaziland waste regulations 2000 section 5 (1) (b) which states that, no person shall dispose of special waste except at an approved waste disposal facility (SEA and UNEP) [6]. This raised a concern to the researchers that the problem of improper disposal of used sanitary napkins and other menstrual wear might not be only a problem of the few schools observed, but could be an entire country’s experience. In addition, the researchers took note of the fact that menstrual hygiene is quite often a neglected issue in the WASH programme. Due to these observations, the researchers deemed it prudent to conduct a study on menstrual hygiene practices and its management in the public boarding schools where the issue of menstruation is still new to the adolescent girls. While disposable menstrual wear has been hailed as an advantage for women in terms of comfort and convenience, it contributes to a major human impact on the environment. The increased use of disposable menstrual products may lead to Environmental pollution [3,7].

The main focus of the study was to assess the menstrual hygiene practices and management of menstrual waste in public boarding schools in the Hhohho. Specifically, it aimed at investigating the methods used to dispose menstrual waste by the girls in secondary boarding school in the Hhohho region; and identify the problems associated with the handling of menstrual wastes in the boarding schools. The researchers hoped that the study will equip the boarding secondary school girls and the waste handlers with the necessary information on proper management of wastes emanating from menstrual flows. Improvements on the current disposal methods will also be ensured through the study by the suggestion and recommendations for proper waste management practices and disposal methods that can be effectively implemented in boarding schools in the country. Other institutions that also generate such waste for instance boarding primary and tertiary institutions can also benefit from the study. The study was hoped to bring to the attention of health workers and educators the need to incorporate menstrual hygiene management in WASH programmes, as well as the need to integrate menstrual issues in health awareness lessons in schools. Finally the study will act as a baseline on which other researchers can develop detailed studies on the challenges and management of menstrual hygiene in Swaziland.

Challenges surrounding menstrual hygiene practices and management

The main challenges surrounding menstrual hygiene management as reported by Patkar and Vaughn [4,8]:

Menstruation is not something to be proud of. It is surrounded by silence, shame and social taboos that are further manifested in social practices that in many cultures restrict mobility, freedom and access to normal activities and services.

Menstruating women and girls are considered impure, unclean, and unfit for the public sphere. This perception is exacerbated by the lack of washing and bathing facilities, materials and spaces that can help women and girls manage the menstrual discharge with dignity and safety.

Sanitation and hygiene facilities conception and design completely ignore this need of women and girls to manage menstrual discharge. Hygiene programmes ‘teach’ girls and women how to be hygienic without explicitly providing the requisite materials, spaces, water and washing agents that cater for menstruation. By ignoring disposal facilities and mechanisms for contaminated materials, they reinforce the stigma and shame surrounding menstruation.

By talking about gender and user friendly design but remaining silent about menstruation, programmatic discourse reinforces stereotypes and refrains from breaking taboos and a view of the world that systematically ignores female users. WASH projects across the world focus on women because they are the de facto managers and ensure proper use, maintenance and sustainability. Very few of these address the menstrual water, sanitation and hygiene needs of women.

The practical dimensions are well recognized. Poor menstrual hygiene is linked to high reproduction tract infections, urinary tract infections, bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal cardiosis and dysmenorrhoea – indicating linkages with higher anaemia and infertility.

Boys and fellow girls find menstruating colleagues smelly and objectionable. This makes the girls to simply stay home from school in order to deal with menstruation and to avoid staining their clothes and embarrassment. This results in the girls falling behind in their studies and renders them unable to learn due to abdominal pain and menstrual hygiene management related stress and they eventually drop out or do not continue with their education as the onset of puberty and changes in their bodies are unmatched with the available facilities and a conducive environment at the schools.

The onus of managing menstruation is on women and girls. They are asked to do this silently and in a way in which society at large can deny the phenomenon itself. Talking about it is shameful and indecent. Research does not reveal any direct or substantive health impacts from poor or good menstrual practices. So practitioners and policy makers remain sceptical, the question is why bothered changing taboos, perceptions and practices that are as old as the earth itself?

Interaction of sanitation systems with menstrual practices and management

A majority of poor women in developing countries cannot afford modern menstrual products to manage menstrual hygiene [4]. As such, they resort to the use of old clothes or cotton wool to absorb menstrual blood. However, Sebastian et al. [9,10] argue that, based on trade data, a dramatic increase in imports of feminine hygiene products to developing countries has been observed over the past few decades. Sebastian et al. [9] further state that, the interaction of sanitation systems with women menstrual management is an underrepresented area of sanitation research. These authors emphasize three critical ways that link menstrual management to sanitation. Firstly, more women and girls are struggling to access appropriate space to deal with their menstrual challenges, which impact their work and participation in school adversely. Secondly, there are insufficient washing facilities that can contribute to hygiene related health problems. And, thirdly, there is sufficient evidence that both disposable and reusable menstrual management materials are found in sanitation systems in developing countries.

Unless appropriate waste facilities are put in place and properly used, the improper disposal of menstrual waste through sanitation systems will continue, leading to blockages, overflows and failure in other systems. It is estimated that in a period of six weeks 12,259,135 women aged 15 to 49 in Sub- Saharan Africa (low income and low to middle income countries) use flush toilet to dispose of their menstrual napkins, 64,574 628 use pit latrines, and 29,970,355 have no facilities and 13 361 409 use other types of facilities [9,11]. Sebastian et al. [9] further state that for the same six weeks and age group, it is estimated that 27,487,501 use flush toilets, 874 833 use pit latrines, 2,693,296 have no facility and 7,34,485 use other types of facilities in the Middle East and North Africa (low income and low to middle income countries). This aggravates the extent to which humans and the environment get exposure to pollution emanating from menstrual flow management.

Sanitation systems and menstruation patterns

The magnitude of the problem caused by menstrual wastes in sanitation systems varies in accordance with the type of sanitation system used. An example is the disposal of menstrual wastes in pit latrines which has less functional problems, but has serious problems in piped systems. This emphasizes the fact that the magnitude of the problem caused is directly related to the sanitation system in use. In their findings, Sebastian et al. [9] show that a large proportion of households in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia do not have access to any form of sanitation facilities (32 percent in each region) which raises concerns with respect to privacy during menstruation.

Adamcová et al. [12] and also Sebastian et al. [9] point out that if households do not have good options for solid waste and also menstrual waste disposal, pressure may be exerted on sanitation systems. Flush toilets are expected to be the most vulnerable system to sanitary waste. Although system failure is major concern in flush toilets, proper waste disposal and privacy are of utmost concern for women using pit latrines and those without access to any sanitation system [13]. From Sebastian et al. [9] study it is worth noting that menstrual waste poses various threats to sanitation systems, but each system needs attention in meeting proper waste disposal and privacy needs for menstruating women and girls.

Elements of disposable products from menstrual hygiene materials

Disposable menstrual hygiene products consist of plastics in the products themselves and their packaging; bleaches to whiten cotton; adhesives to fix napkins to underwear; and fragrances to mask odours and other elements. In addition, reusable products can contain fabric dyes, plastics for menstrual cups and some packaging, amongst other elements (Women’s Environmental Network) [14]. The impact of reusable menstrual products on the environment is substantially less than disposable products Maradas which are disposed of after every use.

Relationship between menstrual hygiene and water, sanitation and health (WASH)

If girls and women are to live healthy, productive and dignified lives, it is necessary that they are able to manage menstrual flow effectively. Therefore, access to appropriate water, sanitation and hygiene services, including clean water for washing their clothes that are used to absorb menstrual blood, and having a place to dry them, having a private place to change clothes or disposable sanitary napkins, facilities for disposal of used clothes and napkins and access to information to understand the menstrual cycle and how to manage menstruation hygienically are the prerequisites for effective menstrual bleeding management [15,16]. This calls for the promotion of awareness among women and men to overcome the embarrassment, cultural practices and taboos surrounding menstruation that have a negative impact on women’s and girls’ lives and reinforcement of gender inequalities and exclusion [2,4]. Although WASH programmes have successfully promoted affordable production and supply of soap and toilet construction materials for poor communities, the availability of affordable sanitary napkins and containers for collection and storage remains a challenge in secondary schools [2].

Main Impacts of Poor Menstrual Hygiene and Management

Impact on girls’ education

One main problem is the impact of cultural practices and lack of services for menstrual hygiene management on girls’ access to education [17]. A study in South India reported that half the girls attending school were withdrawn by their parents once they reached menarche, mostly to be married. This was either because menstruation was perceived as a sign of readiness for marriage, or because of the shame and danger associated with being an unmarried pubescent girl [18]. Even if girls are not completely withdrawn from school, menstruation affects attendance for most of the girls. Lack of privacy for cleaning and washing is the main reason for absenteeism, other key factors being the lack of availability of disposal system and water supply [19]. A majority of girls often perform poorly when they do attend school during menstruation, due to the fear that boys would realize their condition [20]. Similar findings were reported by a survey undertaken by Water Aid in India, in which 28 per cent of students reported not attending school during menstruation, due to lack of facilities. A study of 4,300 primary schools by UNICEF and the Government of Bangladesh found that 47 per cent had no functioning water source, 53 per cent did not have separate latrines for girls, and on average the schools had one latrine serving 152 pupils [21]. Only 42 per cent of the girls in the Nepal study had access to a toilet with adequate privacy at school.

Impact on girls’ health

The studies discussed in this paper suggest that clear links exist between poor menstrual hygiene which include re-using of cloths that have not been adequately cleaned and dried, and not being able to wash regularly, and urinary or reproductive tract infections and other illnesses. However, there is no clear and sound medical analysis that supports these findings. It is for that reason that it cannot be proven that a causal relationship exists between these factors. On the other hand, anecdotal evidence does support a connection. For example, respondents in a survey by Water Aid in Bangladesh are said to have reported health problems such as vaginal scabies, abnormal discharge, and urinary infections, and associated these with menstrual hygiene [22]. This highlights a need for scientific research, in order to better understand the impact of poor menstrual hygiene on health.

Impact on development goals

The effects of neglecting menstrual hygiene and management (on social exclusion, access to water, sanitation and hygiene services, education and health) have a potential to affect the achievement of the development goals which governments, donors and agencies have committed through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [18] and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Given the potential of a focus on menstrual hygiene to support the achievement of global targets, it is of utmost necessity that development professionals and their agencies incorporate this issue into their work. This also requires establishment of greater links between the relevant sectors, including WASH, health and education [2].

Menstrual waste disposal

The general practice that people are comfortable with is to dispose of menstruation waste in toilets or rubbish bins, some also prefer burning them. Rural women usually rinse the blood first prior to disposing, reason being the belief that blood is sacred and it should not be left around in the open [23]. Disposal of menstrual waste is influenced by location. Women dispose waste differently depending on where they are at that point in time. Their behaviour when they are at home is different from when they are in public places. In public places the behaviour of women from rural areas who are used to using pits changes depending on the type of toilet being used. This means that if they are using flush toilet, they flush down the menstrual products into the toilet. If it does not flush, they take it out, wrap it in toilet paper and throw it in dustbin inside the toilet, some wrap it and take it home with them to dispose of in their pit toilets [24]. In suburbs and formal townships the common behaviour is to throw menstrual wastes in bins or to flush them down the toilet or sometimes burning them [25].

An average woman throws away an astonishing 125 to 150 kg of tampons, napkins and applicators in her lifetime [18]. This same author went on to say that disposal of menstrual products is a major problem. Along with cotton buds, tampons, applicators and panty liners make up 7.3% of items flushed down the toilet in the United Kingdom. Even products that are described as flushable or biodegradable can contribute to more than half of sewer flooding due to blockages in sewers. Therefore, no matter what it says on the packaging, most personal healthcare and beauty products should never be disposed of down the toilet. The chlorine bleaching of pulp produces dioxins, a known human carcinogen, and highly toxic environmental pollutants with serious health implications. Women’s Environmental Network’s first campaign persuaded manufacturers to change the bleaching method and they now use either chlorine dioxide or hydrogen peroxide, which produces less dioxin. However, there are currently no controls or testing on the levels of dioxins in tampons and sanitary napkins .While chlorine-free bleaching processes are available, most woodpulp manufacturers only use elemental chlorine-free bleaching processes, which still use chlorine dioxide as a bleaching agent, and therefore still produce dioxin [18].

In the absence of proper sanitation and disposal infrastructure, the indiscriminate disposal of sanitary napkins may lead to severe health, aesthetic and social issues. Mass education campaigns are required for rural as well as urban areas for safe disposal of sanitary napkins along with providing feasible options. Incinerators with appropriate and approved technology or deep burial in pits to be covered with lime and mud are some of the options available. There are designs available for convenient and cost-effective incinerators that can be installed in schools, colleges, hostels and at community level. In various schools in Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, incinerators have been installed and used regularly [18]. The use of incinerators has removed inhibitions among girls attending schools during menstruation. At household level, disposal can still be a problem as open burning may cause foul smell; it is not environmentally friendly and it requires open space which raises the taboo issue. Burying the used napkin is subject to digging by stray animals. Using plastic bags for disposal of used napkins can slowly become an environmental hazard. A public private partnership to manufacture environmentally friendly wrapping material for discarding the napkins may prove useful. It is suggested that the policy makers should identify methods of disposal which are practically feasible and promote good disposal [24,26].

Methodology

The study was descriptive in nature and followed a quantitative approach. It was conducted in three of the four boarding public secondary schools in the Hhohho region. The target population in each school was first grouped according to their grades then random selection of participants was done in each of these strata. Stratified random sampling was used to select participants to the study from the target population. Boarding girls from form one to form five or form six in all the 3 schools were eligible to participate in the study. Waste collectors/cleaners were also eligible to participate in the study. The sample size was calculated using RAOSOFT sample size calculator. With a margin of error of 10%, confidence level of 90% and a response distribution of 50% the calculation gave a total sample size of 128 out of a total population of 348 boarding girls from the three schools.

A questionnaire was used to collect data from selected subjects of the population. The questions asked were aimed at answering the objective of the study. Reliability and validity of the study was achieved by pre-testing the questionnaire at a boarding School in the Manzini region. The data were treated with strict confidentiality and were only used for the purposes of the study. The data was analyzed and organized through a Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 17) and Microsoft Excel and present in figures, tables, and narrative form. An informed consent was obtained from the participants of the study to ensure that they are well informed in details about the study prior to their agreement to participate. Strict confidentiality of data was ensured. Respect was also given to the culture of the respondents and the participants were organized into a classroom where they filled in the questionnaires in the absence of the researchers as it is not culturally acceptable for males to discuss issues of menstruation with girls/women.

Results and Discussion

The data showed that all respondents (100%) use sanitary napkins to contain menstrual blood during menstruation. This finding is contrary to that in a study by Dasgupta [24] in West Bangal where only 11.25% of the girls used sanitary napkins. Flush toilets were found to be the only type of sanitary facility used in all three schools as 100% of the respondents in the study indicated that they use flush toilets. The implication of this finding in this current study is that, toilet blockage problems are more likely to occur in the flush toilets in schools as also highlighted by [27-29]. The use of sanitary napkins also implies that used napkins are more likely to be disposed of in the general waste rubbish bins in the schools premises if a proper and effective management programme of such waste is not put in place and implemented as supported by Crofts et al. [27] and Sommer [25] who stated that among the Low Income countries sanitary napkins find their way to toilets and rubbish bins.

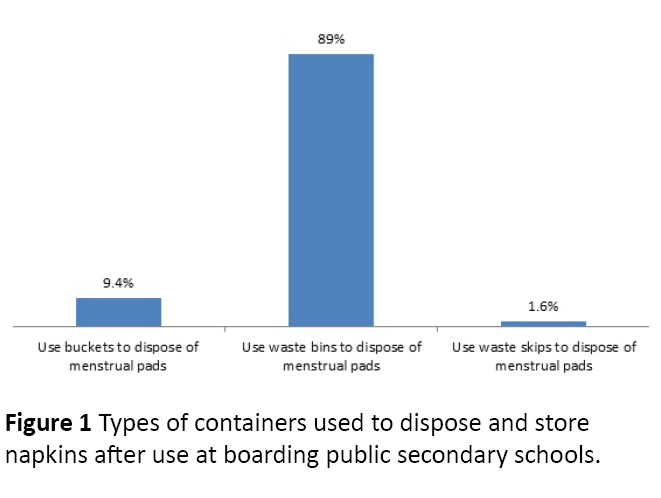

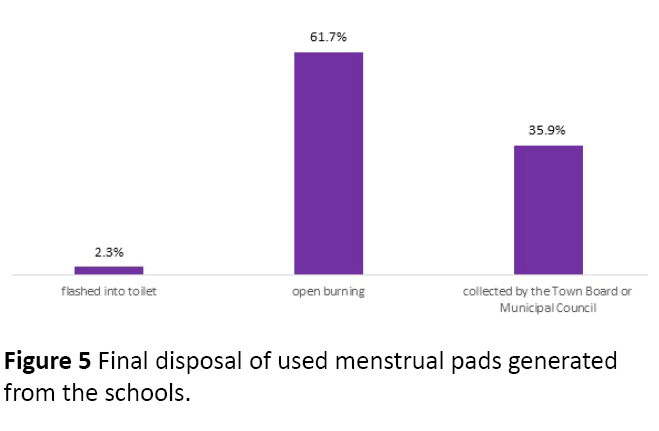

Figure 1 shows the type of containers used to dispose of and store used napkins by boarding girls in secondary schools in the Hhohho region after use. A majority (89%) of the pupils disposed menstrual napkins into waste bins, 9.4% in buckets and 1.6% in waste skips after use. Table 1 shows that 97.7% of the containers for disposing of menstrual napkins after use are kept in the toilets where students change their sanitary napkins while 2.3% of these containers are kept in the school yard (waste skips). The data show that all sampled schools provided containers in the girls’ toilets for disposing of used napkins which is a good practice as they are close to where the waste is generated thus reducing the possibility of napkins being flushed down the toilet due to unavailability of storage containers and taboos associated with carrying napkins a long distance for disposal. This practice however increases the chances of blood leakages and exposure of the users and cleaners of the toilets to contact with menstrual blood and, thus, risks getting infections.

Figure 1: Types of containers used to dispose and store napkins after use at boarding public secondary schools.

Table 1 Location of the containers to dispose of menstrual napkins in the boarding public secondary schools.

| Response |

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

| |

In the toilet |

125 |

97.70% |

| |

School yard |

3 |

2.30% |

| |

Total |

128 |

|

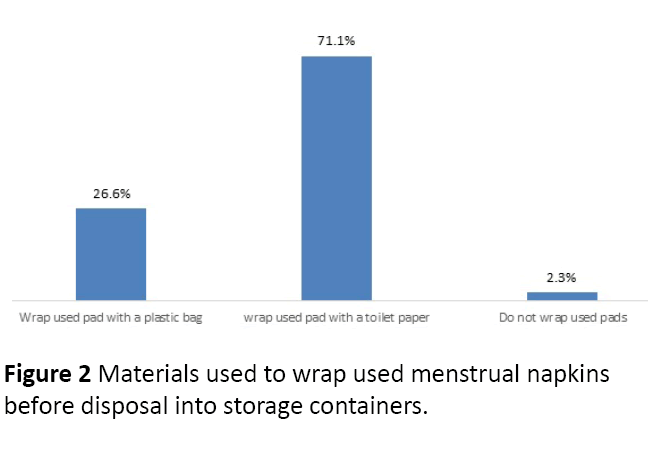

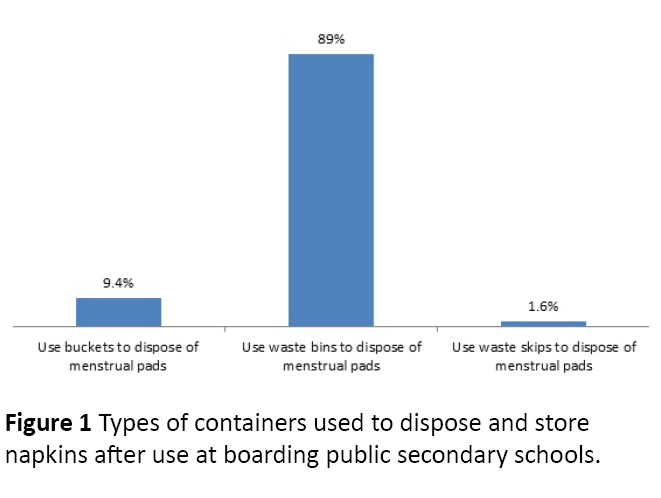

The respondents wrap used napkins before disposing of into the storage containers (Figure 2). Majority 71.1% of the respondents wrapped the used napkins with a toilet paper, 26.6% wrapped the used napkins with a plastic bag and only 2.3% of the respondents did not wrap the used napkins which agree fairly well with [24,27,28]. The high number of girls (71.1%) who use toilet papers to wrap used menstrual napkins (71.1%) and the 2.3% who do not wrap their used menstrual napkins imply high chances of waste handlers and other users of the toilets getting in contact with menstrual waste as menstrual blood can easily leak to the bottom of the bins and will need to be washed after waste disposal.

Figure 2: Materials used to wrap used menstrual napkins before disposal into storage containers.

In addition this practice can allow insects such as cockroaches, flies and other vectors (e.g. rodents) to get in contact with the menstrual blood and expose waste handlers and other dwellers in the schools premises to blood borne diseases as supported by the Queensland Government [1]. The use of plastic bags to wrap used menstrual napkins also has negative effects on the environment due to persistence and resistance to degradation. This exposes other organisms not only to menstrual blood, but also they are hazardious to other animals as they may eat or get entangled in the plastics as also pointed out by Miller and Spoolman [29].

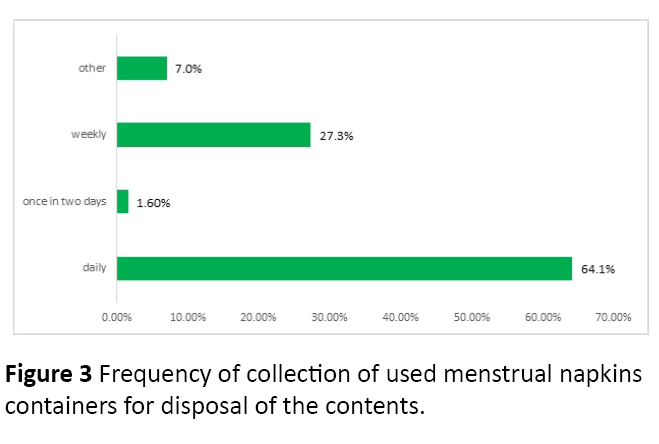

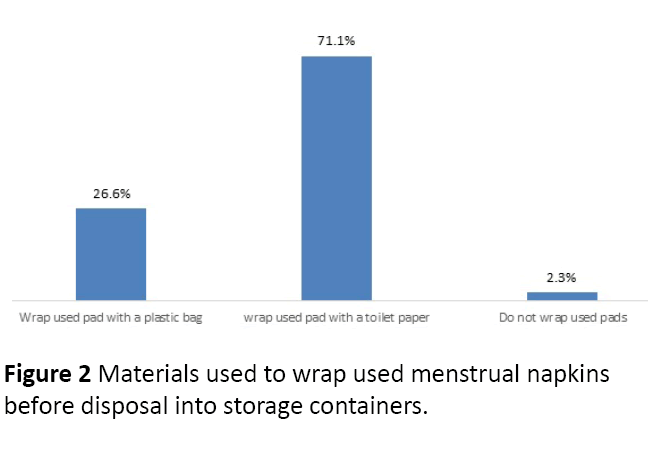

Figure 3 shows the frequency of collection of used menstrual napkins containers for the disposal of the contents. A large portion (64.1%) of the respondents indicated that the containers for used menstrual napkins were collected daily for disposal, 27.3% indicated that the containers for used menstrual napkins were collected weekly for disposal of the contents, 7% indicated other frequencies (twice and three times a week) and the least (1.6%) stated that the used menstrual napkins containers were collected once in two days for disposal of the contents. Ideally, used menstrual napkins containers are collected daily for disposal of the contents to avoid leaks, contact with waste handlers and vectors, and foul odour in the toilets.

Figure 3: Frequency of collection of used menstrual napkins containers for disposal of the contents.

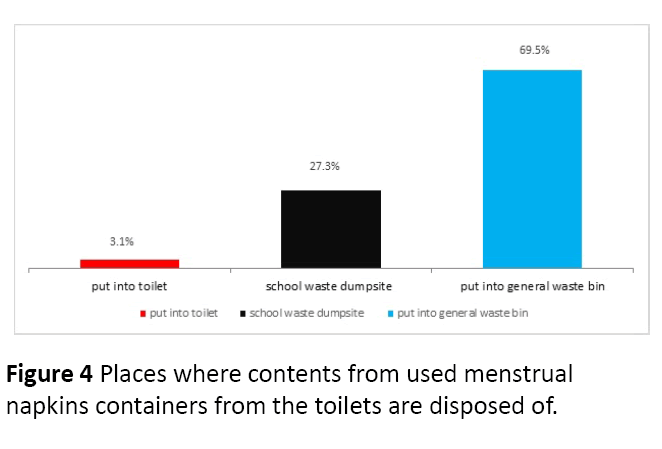

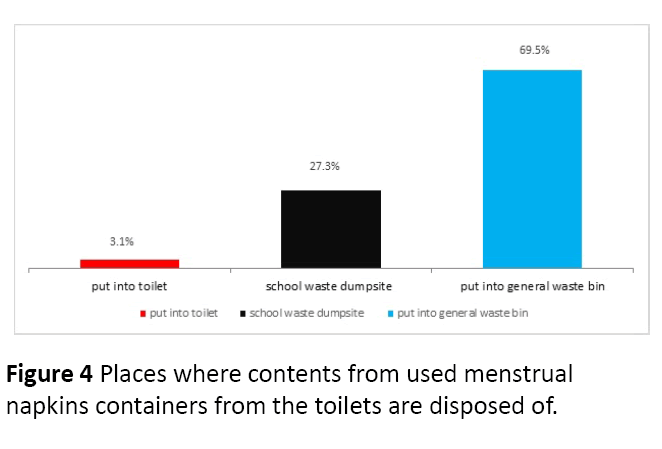

Figure 4 shows that 69.5% of the girls empty the contents from the menstrual napkins containers from the toilets into the general waste bin the school premises, 27.3% dispose the waste from these containers in open dumpsites within the schools’ premises and 3.1% empty the contents directly into the toilets.

Figure 4: Places where contents from used menstrual napkins containers from the toilets are disposed of.

These findings imply that napkins are not segregated and handled separately from other wastes in these schools as they are mainly put together with other general waste in the general waste bins around the schools’ premises (69.5%). This practice can promote the generation of foul smells from waste bins and also expose waste handlers and other dwellers within the school premises to blood borne diseases. The 27.3% of the respondents who stated that they dispose of used menstrual napkins in dumpsites in their respective schools can create un aesthetic conditions, foul odours and cause spread of used menstrual napkins around the schools premises by stray animals such as dogs and thereby creating nuisance.

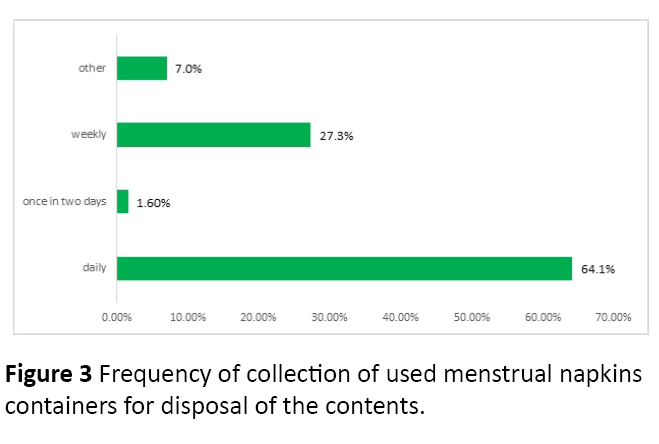

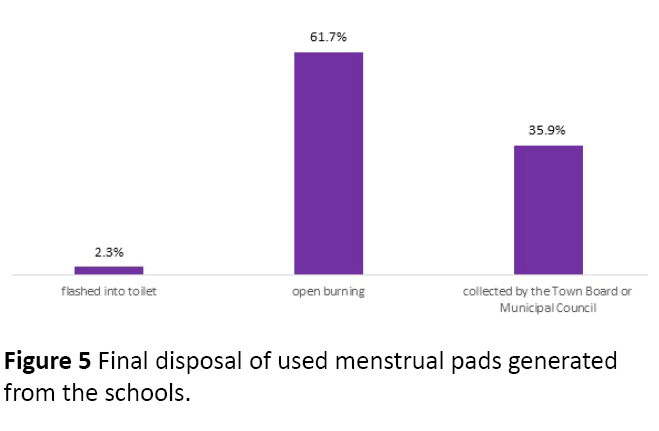

The most common way of treating the menstrual wastes was open burning (64.1% of the respondents) and 35.9% of the respondents indicated that they did not have incinerators or open burning places at the schools for dealing with such wastes. Figure 5 shows that out of the 64.1% of the respondents who use an open burning place, the majority (61.7%) use open burning place compared to the minority (2.3%) who still prefer to flush the used menstrual napkins down the toilet. Figure 5 also shows that 35.9% respondents who do not have either an open burning place or an incinerator at the school said their used menstrual napkins wastes are collected by the town board or Municipal Council for final disposal.

Figure 5: Final disposal of used menstrual pads generated from the schools.

These findings are in line with those of Sommer [25] who found that in suburbs and formal townships, the common behaviour of girls is to throw used menstrual napkins in bin or flush them down the toilet or sometimes burn them. The finding of this present study imply that the air around the schools is polluted during the burning of used menstrual napkins as supported by UNESCO [26] that open burning of menstrual napkins can cause foul smell and is not environmentally friendly. The collection of napkins by Town Board or Municipal Council workers can expose such workers to blood borne diseases especially where they do not used personal protective equipment (such as gloves) during waste collection. However, this is a good practice as the wastes can end up disposed of in sanitary landfills and thus, avoid environmental pollution [30,31].

Conclusion

The practice and management of menstrual hygiene by public boarding school girls in the Hhohho region is not done properly. The data underscored the practices and management of menstrual hygiene by the boarding schools girls and clearly showed that the used napkins are mainly placed in bins in the toilets which can pose a health threat to the cleaners, toilet users, and dwellers in the school premises. The storage and disposal methods were also shown by the data to be wanting and need to be corrected.

Recommendations

1. Government should integrate menstrual hygiene in WASH programme in schools. This will address the issue of menstrual hygiene amongst the girls and also the challenge of menstrual napkins disposal in a sanitary manner.

2. The schools’ administrations should increase the frequency of menstrual waste collection from girls’ toilet for disposal. The cleaners should collect and dispose of menstrual waste from the toilet bins at least two times daily. This will alleviate the challenges of odour, leaks, and contact by individuals and vectors.

3. The schools should put programmes in place to sensitize and empower the pupils (boys and girls) about menstruation and the challenges of practices and management of menstrual hygiene such as waste collection, segregation, storage, disposal, taboos surrounding menstruation, and blockages of toilets due to disposal of used menstrual napkins.

4. Boarding schools should shift from open burning and disposing of menstrual waste in general waste bins to the use of sanitary landfills and incinerators. This will help minimise the pollution challenges caused by such indiscriminate disposal to the environment. Incinerators reduce the bulk of the waste and only a small infection free quantity of ash is realised and disposed of in the sanitary landfills. This minimises the amount of harmful gaseous emissions to the atmosphere from the open burning of waste, and environmental pollution due to incomplete burning of used menstrual napkins.

5. Boarding schools’ administrations should develop and implement regulations and procedures for managing menstrual waste which provide clear guidance and information on how to handle, store, transport and dispose of the menstrual wastes in boarding schools.

21411

References

- Mahon T, Fernandes M (2010) Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: A neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) Programmes. Water Aid, London.

- Jasper C, Le TT, Bartram J (2012) Water and sanitation in schools: A systematic review of the health and educational outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9: 2772-2787.

- Mahon T, Tripathy A, Singh N (2015) Putting the men into menstruation: The role of men and boys in community menstrual hygiene management. Waterlines 34: 7-14.

- Scorgie F, Foster J, Stadler J, Phiri T, Hoppenjans L, et al. (2016) Bitten by shyness: Menstrual hygiene management, sanitation, and the quest for privacy in South Africa. Med Anthropol 35: 161-176.

- SEA, UNEP (2005) Compendium of environmental laws of Swaziland. Mbabane: Swaziland Environment Authority and Environment Programme.

- Lynch P (1996) Menstrual waste in the backcountry. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Vaughn JG (2013) A review of menstruation hygiene management among school girls in Sub-Saharan Africa. Masters\degree thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

- Sebastian A, Hoffman V, Adelman S (1996) Needs and trends in menstrual management: A global analysis.

- Sebastian A, Hoffmann V, Adelman S (2013) Menstrual management in low-income countries: needs and trends. Waterlines 32: 135-153.

- Bharadwaj S, Patkar A (2004) Menstrual hygiene and management in developing countries: Taking stock. Menstrual Hygiene and Management.

- Adamcová D, Vaverková MD, Stejskal B, BÃ…Âââ€Ã

¾¢oušková E (2016) Household solid waste composition focusing on hazardous waste. Pol J Environ Stud 25: 487-493.

- Sommer M, Kjellén M, Pensulo C (2013) Girls' and women's unmet needs for menstrual hygiene management (MHM): The interactions between MHM and sanitation systems in low-income countries. J Water Sanitation Hyg Dev 3: 283-297.

- Women’s environmental network (2012) Seeing red: Sanitary protection & the evironment.

- Garg R, Goyal S, Gupta S (2012) India moves towards menstrual hygiene: subsidized sanitary napkins for rural adolescent girls-issues and challenges. Maternal and Child Health J 16: 767-774.

- Hennegan J, Montgomery P (2016) Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low and middle income countries? A systematic review. PlOS One 11: e0146985.

- Tegegne TK, Sisay MM (2014) Menstrual hygiene management and school absenteeism among female adolescent students in Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 14: 1118.

- Ten VTA (2007) Menstrual hygiene: A neglected condition for the achievement of several millenium development goals. Europe External Policy Advisors.

- Bodat S, Ghate MM, Majumdar JR (2013) School absenteeism during menstruation among rural adolescent girls in Pune. Natl J Community Med 4: 212-216.

- Water Aid in Nepal (2009) Is menstrual hygiene and management an issue for adolescent school girls? Water Aid.

- Nahar Q, Ahmed R (2006) Addressing special needs of girls challenges in schools.

- Ahmed R, Yesmin K (2008) Menstrual hygiene: Breaking the silence. Water Aid.

- El-Gilany AH, Badawi K, El-Fedawy S (2005) Menstrual hygiene among adolescent school girls in Mansoura, Egypt. Reprod Health Matters 13: 147-152.

- Dasgupta A, Sarkar M (2008) Menstrual hygiene: How hygienic is the adolescent girl? Indian J Community Med 33: 77-80.

- Sommer M (2011) Global review of menstrual beliefs and behaviours in low-income countries: Implications for menstrual hygiene management. University of Maryland, USA.

- UNESCO (2014) Puberty education and menstrual hygiene management: Good policy and practice in health education.

- Crofts T, Fisher J (2012) Menstrual hygiene in Ugandan schools: an investigation of low-cost sanitary napkins. J Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 2: 50-58.

- Kjellén M, Pensulo C, Nordqvist P, Fogde M (2012) Global review of sanitation system trends and interactions with menstrual management practices. Report for the Menstrual Management and Sanitation Systems Project, Stockholm Environment Institute, Sweden, Project Report.

- Miller TG, Spoolman SE (2016) Living in the environment (18th edn.). National Geograpic Learning and Cengage Learning, Stamford.

- Madaras L (2007) The what’s happening to my body. Newmarket Press, New York.

- Partkar A (2001) Menstrual hygiene management: Preparatory input on MHM for end group.