Review Article - (2023) Volume 17, Issue 6

PRIMARY NON-HODGKING LYMPHOMA OF COLEDOCO, WHICH SIMULATES CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA DIAGNOSED BY ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASONOGRAPHY: CASE REPORT AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Renzo Pinto Carta1,

Fernando Sierra Arango2,

Faruk Hernandez Sampayo3*,

Eduardo Cuello Navarro4 and

Jorge Galvis Ordonez5

1Gastroenterology, Digestive Endoscopy and Hepatology Section, Hospital Universitario Fundación Santafe de Bogota, Colombia

2Pathology Department, Hospital Universitario Fundacion Santafa de Bogota, Colombia

3General Surgeon, Universidad Metropolitana, Fellow in Gastroenterology, Universidad de Cartagena, Colombia

4General Physician, Fundacion Santafe de Bogota, Colombia

5Resident Surgeon, Fundacion Santafe de Bogota, Colombia

*Correspondence:

Faruk Hernandez Sampayo, General Surgeon, Universidad Metropolitana, Fellow in Gastroenterology, Universidad de Cartagena,

Colombia,

Email:

Received: 01-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. Iphsj-23-13853;

Editor assigned: 03-May-2023, Pre QC No. Iphsj-23-13853;

Reviewed: 17-Jun-2023, QC No. Iphsj-23-13853;

Revised: 22-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. Iphsj-23-13853(R);

Published:

29-Jun-2023, DOI: 10.36648/1791- 809X.17.6.1026

Background

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is the term used to describe a

group of diverse types of cancer that share one characteristic:

they arise from a DNA injury in a progenitor lymphocyte,

triggering their excessive growth in the lymphoid organs (nodes).

Gastrointestinal involvement as a primary form is not common

and represents about 10% of cases. However, as an extranodal

secondary form, manifestations are reported in the stomach (50-

70%), small intestine (20-30%), and colon (5-15%) [1].

The liver is involved in 40% of secondary cases; however, primary

non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the liver is extremely rare, representing

less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases worldwide [2]

Primary lymphomas usually have a better prognosis at 5 years,

with survival rates between 62-90% when diagnosed early,

considering advances in chemotherapy (a pillar of treatment).

In the case of secondary lymphomas, which indicate systemic

spread, the prognosis is worse [1].

Involvement of the bile duct is extremely rare, especially as a

cause of jaundice in a patient. Bulent Odemis et al [37]. Conducted

retrospective searches for patients with biliary obstruction due to

lymphoma between 1999 and 2005. Out of 1123 patients, they

reported that the incidence of primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma

in the biliary tract in patients with malignant cholangiocarcinoma

was 0.6%, and primary biliary tract lymphoma represented 0.4%

of extra nodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas and only 0.016% of all

non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases. Its presentation with obstructive

jaundice is mainly due to tumor-related compression in the bile

duct, compression of the extra hepatic ducts by per portal, per

hepatic, or per pancreatic lymph nodes [3, 4].

Some viruses are involved in the pathogenesis of NHL, probably

due to their ability to induce chronic antigenic stimulation and

cytokine dysregulation, leading to uncontrolled stimulation of

B and T cells, proliferation, and lymphoma genesis. Hepatitis B

virus, hepatitis C virus, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, elevated lactate

dehydrogenase levels, or a compromised immune system have

been associated with the development of primary biliary non-

Hodgkin lymphoma [5, 6].

According to a literature review, since Nguyen [7] reported the

first case in 1982, a total of 43 cases have been reported, with

the latest case reported in July 2022 [36]. Therefore, we aimed to

compile all the reported cases worldwide to serve as a supportive

study for future reports of similar cases, including our case number

44 Table 1. It is noteworthy that this is the second report in Latin

America and the first case reported in our country, Colombia.

| S.NO |

Author |

Age (years) |

Gender |

lymphoma subtype |

Treatment |

Follow-up (months) |

Outcome |

| 1 |

Nguyen7 |

59 |

M |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

8 |

Deceased |

| 2 |

Takehara et al.8 |

60 |

M |

Diffuse, Intermediate Size B-Cell |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

Unknown |

Unknown |

| 3 |

Kaplan et al.9 |

42 |

M |

Small Unsplit Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

10 |

Deceased |

| 4 |

Tartar y Balfe10 |

48 |

M |

Unknown |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

14 |

Alive |

| 5 |

Tzanakakis et al.11 |

70 |

M |

Mixed Small and Large B-Cell Diffuse |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

4 |

Deceased |

| 6 |

Kosuge et al.12 |

68 |

F |

Small Unsplit Diffuse Large B-Cell |

Surgery, Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy |

16 |

Deceased |

| 7 |

Brouland et al.13 |

34 |

F |

T-Cell and Large B-Cell |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

48 |

Alive |

| 8 |

Machado et al.14 |

43 |

F |

Mixed Small and Large Nodular B-Cell |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

6 |

Alive |

| 9 |

Chiu et al.15 |

25 |

F |

Mixed Small and Large T-Cell Origin |

Surgery |

12 |

Deceased |

| 10 |

André et al.16 |

44 |

F |

Centrocytic-Centroblastic Follicular |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

48 |

Alive |

| 11 |

Maymind et al.17 |

39 |

F |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery, Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy |

13 |

Alive |

| 12 |

Podbielski et al.18 |

66 |

M |

Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery |

Unknown |

Unknown |

| 13 |

Oda et al.19 |

58 |

M |

Mixed Small and Large B-Cell Diffuse |

Surgery |

32 days |

Deceased |

| 14 |

Corbinais et al.20 |

29 |

M |

High-Grade T-Cell |

Chemotherapy |

12 |

Alive |

| 15 |

Eliason y Grosso21 |

41 |

M |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery |

Unknown |

Unkown |

| 16 |

Gravel et al.22 |

4 |

M |

Pre-B-cell Lymphoblastic Lymphomaw |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

18 |

Alive |

| 17 |

Kang et al.23 |

73 |

F |

Low-grade B-cell MALT |

Surgery |

23 |

Alive |

| 18 |

Young-Eun Joo et al 24 |

21 |

F |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

17 |

Alive |

| 19 |

Yong Keun Park et al 25 |

81 |

F |

MALT |

Surgery |

12 |

Alive |

| 20 |

Carolina De La Rosa et al 26 |

50 |

M |

Large B-cells |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

Unknown |

Unkown |

| 21 |

Min A Yoon et al 27 |

62 |

M |

MALT |

Surgery |

Unknown |

Unknown |

| 22 |

Jiamei Wu et al 28 |

59 |

F |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery |

2 |

Deceased |

| 23 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

11 |

M |

Low-grade B-cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

62 |

Alive |

| 24 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

30 |

F |

Diffuse B-Cells |

Surgery |

3 days |

Deceased |

| 25 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

3 |

F |

Diffuse B-Cells |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

48 |

Alive |

| 26 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

80 |

M |

High-grade B-cell Lymphoma |

Chemotherapy and bone marrow transplant |

72 |

Alive |

| 27 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

60 |

M |

Low-grade B-cell Lymphoma |

Chemotherapy |

18 |

Alive |

| 28 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

55 |

F |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

38 |

Alive |

| 29 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

41 |

M |

Large B-Cells |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

Unknown |

Deceased |

| 30 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

10 |

F |

Large B-Cells |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

4 |

Alive |

| 31 |

KV Ravindra et al 29 |

32 |

M |

Large B-Cells |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

Unknown |

Unknown |

| 32 |

Kasturi Das et al 30 |

36 |

M |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

68 |

Alive |

| 33 |

Kasturi Das et al 30 |

51 |

M |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

18 |

Alive |

| 34 |

F Yoneyama et al 31 |

55 |

F |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

53 |

Alive |

| 35 |

Baron et al 32 |

41 |

M |

Diffuse B-Cells |

Surgery and immunosuppressants |

12 |

Alive |

| 36 |

Baron et al 32 |

59 |

F |

Diffuse B-Cells |

Surgery and immunosuppressants |

24 |

Alive |

| 37 |

Luigiano et al 33 |

30 |

M |

Large B-Cells |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

6 |

Alive |

| 38 |

Gen Sugawara et al 34 |

33 |

M |

Follicular Lymphoma |

Surgery |

12 |

Alive |

| 39 |

Hideaki Dote et al 35 |

66 |

M |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

8 |

Alive |

| 40 |

Nicolás Pararás et al 36 |

61 |

F |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

8 |

Alive |

| 41 |

Bulent ¨ Odemis et al 37 |

57 |

F |

Large B Cells |

Surgery, Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy |

10 |

Alive |

| 42 |

Bulent ¨ Odemis et al 37 |

18 |

M |

Large B Cells |

Surgery |

Unknown |

Deceased |

| 43 |

Bulent ¨ Odemis et al 37 |

64 |

F |

Large B Cells |

Surgery and Chemotherapy |

Unknown |

Unknown |

| 44 |

Nuestro Estudio |

65 |

F |

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma |

Chemotherapy |

In follow-up |

Alive |

Table 1. Review of cases of biliary tract lymphoma worldwide.

Case Report

A 65-year-old female presented with a clinical picture of 24 hours of jaundice associated with generalized pruritus, with emphasis

on the hands and feet. She had been experiencing alcoholic stools

for the past 5 days, along with a feeling of fullness and a 4/10

intensity oppressive pain in the epigastria region that did not

improve despite the use of antacids, leading her to seek medical

attention. She had a history of depression, anxiety, hepatitis

C, Clostridium difficile colitis, and past human papillomavirus

infection. On physical examination, the only positive finding was

jaundice. Laboratory tests showed leukocytes 5900, neutrophils

3200 (54.23%), hemoglobin 13.4, haematocrit 38.5, platelets

150,000, creatinine 0.82, sodium 136, potassium 4.32, chloride

104, partial thromboplastic time (PTT) 24.1/26.9, prothrombin

time (PT) 10.2, international normalized ratio (INR) 0.93. [8-13]

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 196, alanine aminotransferase

(ALT) 456, alkaline phosphatase 486, total bilirubin 10.51, direct

bilirubin 6.93, indirect bilirubin 3.58, gamma-glutamyl transferees

(GGT) 353, CA 19-9 antigen: 2256 U/ml, serum alpha-fetoprotein

4.69, carcinoembryonic antigen 0.85.

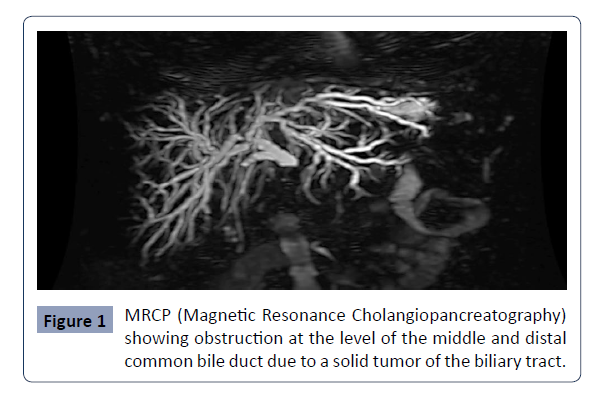

Regarding radiological studies, an ultrasound was performed,

which showed dilatation of the intrahepatic and extra hepatic

bile ducts without being able to establish an obstructive etiology,

hepatomegaly, and post-cholecystectomy state. Based on the

findings, a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

(MRCP) was performed, which revealed focal irregular

thickening of the walls of the distal common bile duct, with

a solid lesion measuring 18 millimeters in diameter, with a

neoplastic appearance, associated with peripancreatic and left

retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, resulting in biliary obstruction

with significant dilatation of the biliary tract in a retrograde

manner (Figure 1).

Figure 1: MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography)

showing obstruction at the level of the middle and distal

common bile duct due to a solid tumor of the biliary tract..

The patient presented with obstructive biliary syndrome, where

a solid lesion associated with lymphadenopathy in the distal

common bile duct and pancreas was documented. The primary

diagnostic possibility established was cholangiocarcinoma.

Endoscopic ultrasound was recommended to better characterize

the lesion and perform a biopsy guided by this method.

Additionally, during the same surgical procedure, endoscopic

retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was indicated for

biliary diversion. Further imaging studies including abdominal/

thoracic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission

tomography (PET scan) were also recommended [13-16].

High-resolution chest MRI

No signs of metastatic disease involvement in the chest

were observed. There is mild centrilobular emphysema and

inflammatory involvement of the medium and small caliber

airways, with sub segmental distribution in the lung bases.

Abdominal MRI

Per pancreatic lymphadenopathy and dilation of the biliary tract,

with collapsed distal bile duct and concentric thickening of the

mid-common bile duct showing high cellularity, consistent with

the lymphadenopathy. The pancreas does not show any lesions,

and the pancreatic duct is not dilated. There are no liver lesions

suggestive of secondary involvement [17-23].

Considering the previous findings, a consultation was made to

the hepatobiliary surgery department, which concluded that

there is likely an end luminal lesion in the mid-common bile duct,

with no evidence of distant metastatic lesions but with local

lymphadenopathy. The patient is deemed a surgical candidate,

and the possibility of performing a pancreatoduodenectomy is

considered.

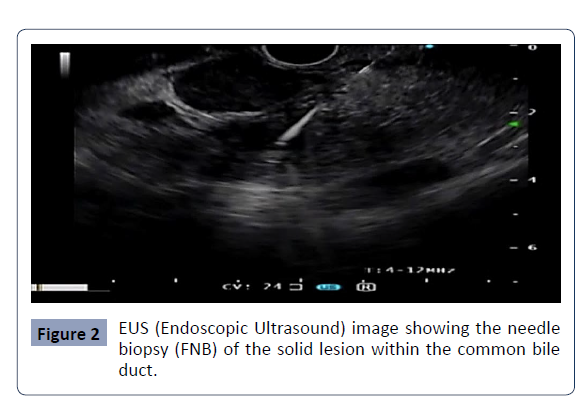

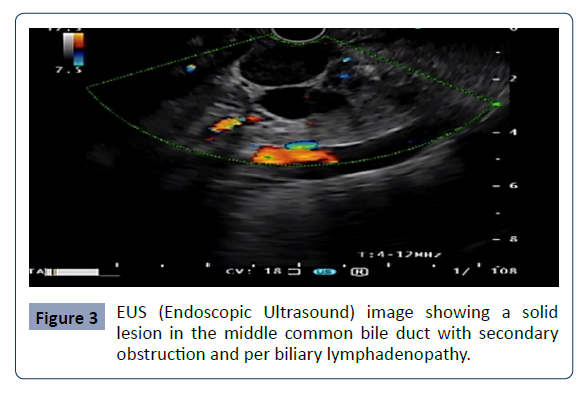

Endoscopic ultrasound was performed, revealing the following

findings: thickening of the walls of the mid-common bile duct due

to a hypo echoic, heterogeneous lesion with irregular borders,

measuring 13 mm in diameter, showing exophytic growth;

per biliary lymphadenopathy, round [24, 25] well-defined,

hypo echoic, homogeneous, with characteristics suggestive of

secondary neoplastic infiltration; and dilation of the bile duct,

with a maximum diameter of 12 mm. A biopsy was performed

using a 22 G acquire needle (fine needle biopsy - FNB) with two

passes using a fanning technique, obtaining adequate material

for histology without complications (Figure 2 & 3).

Figure 2: EUS (Endoscopic Ultrasound) image showing the needle

biopsy (FNB) of the solid lesion within the common bile

duct..

Figure 3: EUS (Endoscopic Ultrasound) image showing a solid

lesion in the middle common bile duct with secondary

obstruction and per biliary lymphadenopathy..

ERCP findings

The ampulla of Vater appears normal in the second portion of

the duodenum. There is dilation of the intrahepatic and extra

hepatic bile ducts, with the common bile duct measuring 16 mm

in diameter and obstruction and stenosis at the level of the midcommon

bile duct. A fully covered self-expandable metal biliary

stent is implanted [26].

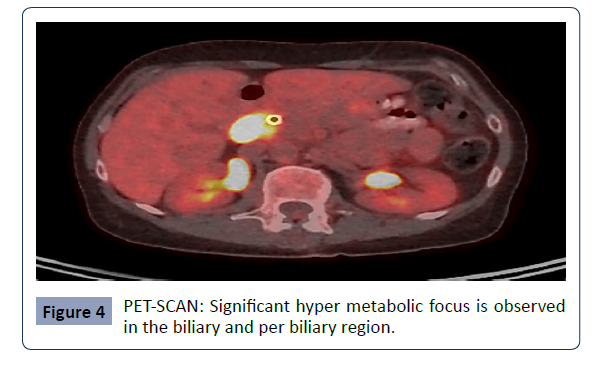

PET scan

Hyper metabolic nodular thickening of the extra hepatic bile

duct in the peri-pancreatic region, suggestive of a tumor. Hyper

metabolic lymph node adjacent to the peri-pancreatic region

(precaval), suggestive of a tumor. The study does not show

evidence of other hyper metabolic lesions suspicious for tumor

involvement (Figure 4).

Figure 4: PET-SCAN: Significant hyper metabolic focus is observed

in the biliary and per biliary region..

The histopathological findings are consistent with a

neoplasm composed of uniform and large lymphoid cells.

Immunohistochemical studies reveal that these tumor cells

express CD20, CD10, BCL6, and BCL2, while they are negative for

C-MYC and MUM1. The cellular proliferation index measured by

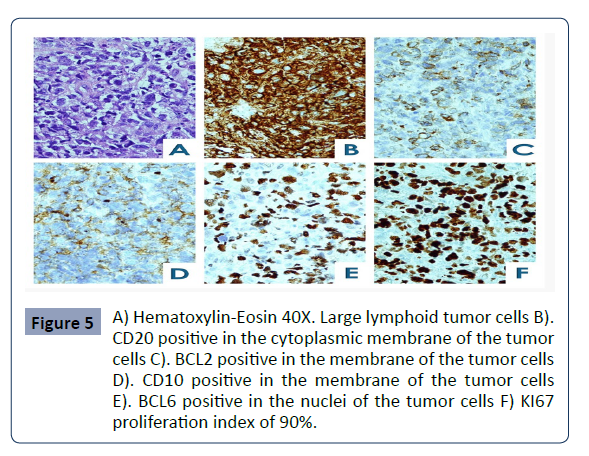

KI67 is 90% Figure 5.

Figure 5: A) Hematoxylin-Eosin 40X. Large lymphoid tumor cells B).

CD20 positive in the cytoplasmic membrane of the tumor

cells C). BCL2 positive in the membrane of the tumor cells

D). CD10 positive in the membrane of the tumor cells

E). BCL6 positive in the nuclei of the tumor cells F) KI67

proliferation index of 90%..

The immunophenotypic analysis by flow cytometry using

the Euro Flow platform shows a polyclonal B-cell lymphocyte

immunophenotypic, with a cellularity of 1%. T lymphocytes

are 7.1% (CD5+), CD4+ cells are 20%, CD8+ cells are 37.1%, and

mature B lymphocytes represent 42.9% of which 29.2% are

kappa-positive and 13.7% are lambda-positive (Figure 5).

In situ hybridization studies are performed, which show no

translocation for BCL2 (18q21), BCL6 (3q27), and C-MYC (8q24).

The immunophenotypic findings are consistent with a diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma, suggestive of a germinal centre origin

[27-33].

Considering the pathological findings, the possibility of surgery is discarded, and the patient is evaluated by the hematologyoncology

department. They initiate immunochemotherapy with

doxorubicin, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and

prednisone (R-CHOP).

Discussion

The worldwide review of case reports Table 1 allows us to

conclude that the average age of presentation is higher in

younger patients, with an average of 46.22 years (4-81 years)

[34-37] including the presence of 3 pediatric patients under 18

years old (4, 10, and 11 years old). These contrasts significantly

with the previously reported average age of 70 years by the

European-American Lymphoma Association [38], indicating

a warning signal to consider it at younger ages. The gender

distribution is comparable, with 54.4% [24] male and 45.4% [20]

female cases. The average follow-up period was 22.6 months,

with 59.09% alive, 22.7% deceased, and 18.1% without reported

outcomes. Regarding histological findings, considering that we

have collected cases from 1982 [7] until the present, there are

variations in the nomenclature. However, we can group them as

follows: 45.4% [20] diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 34% [15] large

B-cell lymphoma, 6.8% MALT lymphoma, 4.5% T-cell lymphoma,

2.2% [1] follicular lymphoma, and in 6.8% [3] the histological type

was not reported.

Regarding the therapy used, 86.3% underwent hepatopancreatoduodenectomy and hepaticojejunostomy with

Roux-en-Y reconstruction, some accompanied by chemotherapy

(69%), and only 9% received chemotherapy as exclusive treatment

[39-41].

It is necessary to highlight that among the 86.3% of patients who

underwent surgery, the diagnosis of primary biliary tract tumor

was made on the pathology specimen, which could have been

avoided if, as in our case, endoscopic ultrasound with biopsy and

needle aspiration (FNB) had been used.

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) groups a series of

prognostic factors that allow predicting the probable clinical course

of NHL. In our case, the IPI was developed and validated before

adding rituximab to curative anthracycline-based chemotherapy [40]. Our patient has an IPI score of 1, indicating a 77%

progression-free survival and 90% overall survival. Clinical trials

[41-44] have confirmed that rituximab can improve the survival

of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and therefore,

the appropriate management for it is immunochemotherapy

with doxorubicin, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and

prednisone (R-CHOP), as in our case (Table 1).

Conclusion

The manifestations of primary biliary tract lymphoma include

jaundice, fever, abdominal pain, weight loss, and the presence

of an abdominal mass. In our case, only pain and jaundice

were present. Primarily, the diagnosis of primary biliary tract

lymphoma is virtually anecdotal, accounting for 0.4% and 0.016% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases [3, 4]. The diagnosis

of primary extra hepatic bile duct lymphoma is challenging

through computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography because in most

cases, the associated clinical and radiological features closely

resemble those of cholangiocarcinoma, and there is no objective

way to differentiate them. Therefore, tissue biopsy is required to

obtain a histological diagnosis, which should become the gold

standard when considering biliary tract surgery. Various methods

are available for biopsy, such as ultrasound-guided biopsy of the

tumor mass or CT-guided biopsy, endoscopic brushings during

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP),

percutaneous trans luminal cholangiography, or cholangioscopy [37]. The success rates of these methods can vary from 20%

to 80% depending on the expertise available at the institution

[39]. Considering the approach, we believe that endoscopic

ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNB) should be

the method of choice for the preoperative evaluation of biliary

tract tumors, as in our case, to avoid unnecessary surgeries and

the associated high morbidity and mortality rates reported, such

as hepatopancreatoduodenectomy and hepaticojejunostomy

with Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

The gold standard treatment for this disease is

immunochemotherapy with doxorubicin, rituximab,

cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) [25,33].

References

- Kimura Y, Sato K, Imamura Y (2011) Small cell variant of MCL is an indolent lymphoma characterized for BM involvement, splenomegaly and low Ki 67. Cancer Sci 102: 1734-41.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Emile JF, Azoulay D, Gornet JM, Lopes G, Delvart V et al. (2001) Los linfomas primarios no hodgkinianos del hígado con patrones de infiltración nodular y difuso tienen diferentes pronósticos. Ana Oncol 12:1005-1010.

Google Scholar

- Severini A, Bellomi M, Cozzi G, Pizzetti P, Spinelli P (1981) Lymphomatous invovement of intrahepatic and extra hepatic Biliary ducts. PTC and ERCP findings. Acta Radiol Diagn 22: 159-163.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Lokich JJ, Kane RA, Harrison DA, McDermott WV (1987) Obstrucción de vías biliares secundaria a cáncer: Guías de manejo y revisión de literatura seleccionada. J Clin Oncol 5: 969-981.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Dlouhy I, Filella X, Rovira J, Magnano L, Rivas-Delgado A et al. (2017) Los niveles séricos altos de receptor de interleucina-2 soluble (sIL2-R), interleucina-6 (IL-6) y factor de necrosis tumoral alfa (TNF) están asociados con características clínicas adversas y predicen un mal resultado en el linfoma difuso de células B grandes. Leuc Res 59:20-25.

Google Scholar, Crossref

- Noronha V, Shafi NQ, Obando JA, Kummar S (2005) Linfoma no hodgkiniano primario del hígado. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 53: 199-207.

Google Scholar, Crossref

- Nguyen GK (1982) Primary extra nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the extra hepatic bile ducts. Report of a case. Cancer 50: 2218-2222.

Google Scholar

- Takehara T, Matsuda H, Naitou M, Sawaoka H, Kin H et al. (1989) A case report of primary extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the extra hepatic bile duct. Acta Hepatol Jpn 88:247-252.

Google Scholar

- Kaplan LD, Kahn J, Jacobson M, Bottles K, Cello J (1989) Primary bile duct lymphoma in the acquired immunodeficiency síndrome (AIDS). Ann Intern Med 110:161-162.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Tartar VM, Balfe DM (1990) Lymphoma in the wall of the bile ducts: radiologic imaging. Gastrointest Radiol 15:53-57.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Tzanakakis GN, Vezeridis MP, Jackson BT, Rodil JV, McCully KS (1990) Primary extra nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the extra hepatic biliary tract. R I Med J 73: 483-486.

Google Scholar

- Kosuge T, Makuuchi M, Ozaki H, Kinoshita T, Takenaka T (1991) Primary lymphoma of the common bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology 38: 235-238.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Brouland JP, Molimard J, Nemeth J, Valleur P, Galian A (1993) Primary T-cell rich B-cell lymphoma of the common bile duct. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 423:513-517.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Machado MC, Abdo EE, Penteado S, Perosa M, da Cunha JE (1994) Lymphoma of the biliary tract: report of two cases. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 49: 64-68.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Chiu KW, Changchien CS, Chen L, Tai DI, Chuah SK etal. (1995) Primary malignant lymphoma of common bile duct presenting as acute obstructive jaundice: report of a case. J Clin Gastroenterol 20: 259-261.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Andre SB, Farias AQ, Bittencourt PL, Guarita DR, Machado MC et al. (1996) Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the extra hepatic bile duct mimicking Klatskin tumor. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 51: 192-194.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Maymind M, Mergelas JE, Seibert DG, Hostetter RB, Chang WW (1997) Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the common bile duct. Am J Gastroenterol 92: 1543-1546.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Podbielski FJ, Pearsall GF Jr, Nelson DG, Unti JA, Connolly MM (1997) Lymphoma of the extrahepatic biliary ducts in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am Surg 63: 807-810.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Oda I, Inui N, Onodera Y, Horimoto M, Watanabe H et al. (1999) An autopsy case of primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the extra hepatic bile duct. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi (Jpn J Gastroenterol) 96:418-422.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Corbinais S, Caulet-Maugendre S, Pagenault M, Spiliopoulos Y, Dauriac C et al. (2000) Primary T-cell lymphoma of the common bile duct. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 24:843-847.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Eliason SC, Grosso LE (2001) Primary biliary lymphoma clinically mimicking cholangiocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol 5:25-33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Gravel J, Lallier M, Garel L, Brochu P (2001) Champagne J Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the extrahepatic biliary tract and gallbladder in a child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 32: 598-601.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Kang CS, Lee YS, Kim SM, Kim BK (2001) Primary low-grade B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type of the common bile duct. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 16:949-951.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Joo YE, Park CH, Lee WS, Kim HS, Choi SK et al. (2004) Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the common bile duct presenting as obstructive jaundice. J Gastroenterol 39:692-396.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Park YK, Choi JE, Jung WY, Song SK, Lee J (2016) Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma as an unusual cause of malignant hilar biliary stricture: a case report with literature review. World J Surg Oncol 14: 167.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- De La Rosa, Carolina Diaz, Uslar Guzman, Jose Clavo, Maria Luisa et al. (2014) Sindrome icterico-obstructivo secundario a linfoma No Hodgkin de células B paracoledociano: a propósito de un caso. Gen 68: 112-115.

Google Scholar

- Yoon MA, Lee JM, Kim SH, Lee JY, Han JK (2009) Primary biliary lymphoma mimicking cholangiocarcinoma: a characteristic feature of discrepant CT and direct cholangiography findings. J Korean Med Sci 24: 956-959.

Google Scholar, Crossref

- Wu J, Zhou Y, Li Q, Zhang J, Mao Y (2021) Primary biliary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 4: e26110.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Ravindra KV, Stringer MD, Prasad KR, Kinsey SE, Lodge JP (2003) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with obstructive jaundice. Br J Surg 90: 845-849.

Indexed at, Crossref

- Das K, Fisher A, Wilson DJ, de la Torre AN, Seguel J (2003) Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the bile ducts mimicking cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery 134: 496-500.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Yoneyama F, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, Nagino M et al. (1998) Primary lymphoma of the liver with bile duct invasion and tumoral occlusion of the portal vein: report of a case. J Hepatol 29:485-488.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Baron PW, Heneghan MA, Suhocki PV, Nuckols JD, Tuttle-Newhall JE (2001) Biliary stricture secondary to donor B-cell lymphoma after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 7: 62-67.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Luigiano C, Ferrara F, Fabbri C, Ghersi S, Bassi M (2010) Primary lymphoma of the common bile duct presenting with acute pancreatitis and cholangitis. Endoscopy 2:E265-6.

Google Scholar, Crossref

- Sugawara G, Nagino M, Oda K, Nishio H, Ebata T (2008) Follicular lymphoma of the extra hepatic bile duct mimicking cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 15:196-199.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Dote H, Ohta K, Nishimura R, Teramoto N, Asagi A et al. (2009) Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the common bile duct manifesting as obstructive jaundice: report of a case. Surg Today 39: 448-51.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Pararas N, Foukas PG, Pikoulis A, Bagias G, Papakonstantinou D (2022) Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the extra-hepatic bile duct: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol 17:115.

Indexed at, Crossref

- Odemiş B, Parlak E, Başar O, Yuksel O, Sahin B (2007) Biliary tract obstruction secondary to malignant lymphoma: experience at a referral center. Dig Dis Sci 52: 2323-2332.

Google Scholar

- Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H (1994) A revised European American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: A propos- al from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 84:1361-1392.

Indexed at, Google Scholar

- Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Sriram PV, Topalidis T, Jaeckle S (2000) EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc 52:534-540.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Un modelo predictivo para el linfoma no Hodgkin agresivo (1993) Proyecto International de Factores Pronosticos del Linfoma No Hodgkin N Engl J Med. 329: 987-994.

Google Scholar

- Dlouhy I, Filella X, Rovira J, Magnano L, Rivas-Delgado A et al. (2017) Los niveles séricos altos de receptor de interleucina-2 soluble (sIL2-R), interleucina-6 (IL-6) y factor de necrosis tumoral alfa (TNF) estan asociados con características clínicas adversas y predicen un mal resultado en el linfoma difuso de células B grandes. Leuc Res 59: 20-25.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

- Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Sriram PV, Topalidis T, Jaeckle S (2000) Citodiagnóstico de colangiocarcinoma hiliar por aspiración con aguja fina guiada por EUS: una serie de casos. Gastrointestinal Endosc 52: 534–540.

Google Scholar

- Kosuge T, Makuuchi M, Ozaki H, Kinoshita T, Takenaka T (1991) Linfoma primario del conducto biliar común. Hepatogastroenterología 38: 235-238.

Google Scholar

- Maymind M, Mergelas JE, Seibert DG, Hostetter RB, Chang WW (1997) Linfoma no Hodgkin primario del colédoco. Soy J Gastroenterol 92: 1543-1546.

Google Scholar

Citation: Carta RP, Arango FS, Sampayo FH, Navarro EC, Ordonez JG (2023) Primary Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma of the Common Bile Duct Mimicking Cholangiocarcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Health Sci J. Vol. 17 No. 6: 1026.