Keywords

Health sector reform, India, Institutional delivery, Polices, Programme, Quality of care

Introduction

Many developing countries since the late 1980s, have initiated efforts to improve their health systems through policies and interventions. The trend toward decentralization of social service delivery and focus on capacity building of health workforce and infrastructure development had been initiated through the National Health Policy and Health, Nutrition and Population Sector Programme (HNPSP) in Bangladesh, (1) and the Social Action Program in Pakistan (2), Several strategies have been tested in the form of introducing user fees, community financing and decentralization in Sub- Saharan African Countries, (3).

As India strives to achieve the fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of reducing the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) from the current level of 254 to 100 by 2015 (4), quality institutional deliveries play a key role in enhancing the survival and well being of both mothers and newborns. The last decade (2000-2010) has witnessed significant expansion in maternal and child (MCH) programmes across India as well as formulation of concrete quality assurance strategies. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) is the flagship health sector reform programme of the Government, launched in 2005, with the goal “to improve the availability of and access to quality health care by people, especially for those residing in rural areas.” The Mission aims at reducing regional imbalances in health by focusing on ‘high-priority’ states (5).

Under NRHM, the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) have been constituted as the basis for ensuring that all levels of primary healthcare services across all states adhere to a set of uniform prescribed norms and standards in terms of physical infrastructure, human resources, services provided, treatment procedures and behavior with patients (6). Quality has thus become explicitly one of the key areas of NRHM, encompassing infrastructural norms as well as service guarantees for vulnerable populations. In terms of long-term vision of NRHM, three key elements of high quality maternal care have been defined as skilled attendance at birth, access to emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC) and efficient referral system for timely access to EmOC (7).

Progress in the health system in India has not been uniform, and significant regional imbalance can be observed in health system development across states. The four Southern states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh and the Western states of Maharashtra and Gujarat are among the states which have shown consistently better health sector performance and health indicators than the less developed states of Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. In maternal health indicators, for example, the MMR in Southern states averages 149 as compared to 375 in the less developed states (4) The primary aim of the paper is to assess the contributing factors and challenges and to generate context-specific implementation lessons from the perspective of the stakeholders in three diverse states in India which are at different levels in terms of delivery of health services. These issues are in the context of the NRHM, one of the major health sector reform programs in India which aims to provide quality delivery care in maternal health services.

Methods

Data

The stakeholders for the study represented respondents at the central and the state levels, which included planners and program managers from the National government as well as the governments of Orissa, Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan and also respondents from development, academic and research institutions (Table 1). Thirty-three in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted in the three states between March and May 2010. A framework of stakeholders was developed to reflect the study setting (context). Interviews were conducted according to a common framework and the paper is part of the broader study to investigate perspectives on current planning and research agenda for quality of care (QOC) in the field of maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH). In the interviews, respondents shared their professional and personal experiences in the four broad areas related to QOC for MNCH. These included: a) The current health sector reform: focus on quality maternal, neonatal and child health; b) Contributing factors; c) Challenges and bottlenecks and d) Implementation lessons.

| Respondent type/category |

Geographic location (state) |

Number of respondents |

| Health and Family Welfare Department |

| Government / TAMIL NADU |

Tamil Nadu |

4 |

| Government / RAJASTHAN |

Rajasthan |

5 |

| Government / ORISSA |

Orissa |

6 |

| Government / CENTRAL |

Central level |

2 |

| Academic/development sector |

| Academia / research institutions |

National |

2 |

| NGOs / National/ State |

National |

4 |

| International NGOs / National |

National |

10 |

| TOTAL |

|

33 |

Table 1: Stakeholder Framework.

Analysis

The analysis presented is qualitative and descriptive. The narratives have been analyzed using a combined inductive/ deductive approach. In this analysis, data were coded according to the interview discussion (‘topic’) guide (which also serves as the initial analytical framework). Through an iterative process of reviewing, and re-reviewing transcripts, data were also coded according to emergent themes. A descriptive analysis is presented to provide an overview of common issues and themes that arose in the discussions.

Selection of Study States

This paper is based on a study that was conducted in India at the national and state levels, which have historically varied levels of health and development performance. In order to highlight the context of quality of care in maternal health post NRHM, indicator of MMR was taken as criteria to select the states, where the states are ranked as excellent, moderate and low performing. But for the present analysis the categorization of the states is at two levels, Tamil Nadu the better performing state and Orissa and Rajasthan as low performing states, which are also based on NRHM classification of nonhigh and high focus states.

The three states selected for the study, Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan and Orissa, are at different levels in terms of maternal outcomes (4). Though in all the states there is visible improvement over the years, but still in the states of Orissa and Rajasthan MMR is above the national average (Figure 1). Tamil Nadu is one of the few states in India which has already reached the MGD 5.

Figure 1: Trend in Maternal Mortality Ratio: A comparative scenario among the study states.

The research was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the institution conducting the study and also written consent was obtained from the stakeholders.

Results

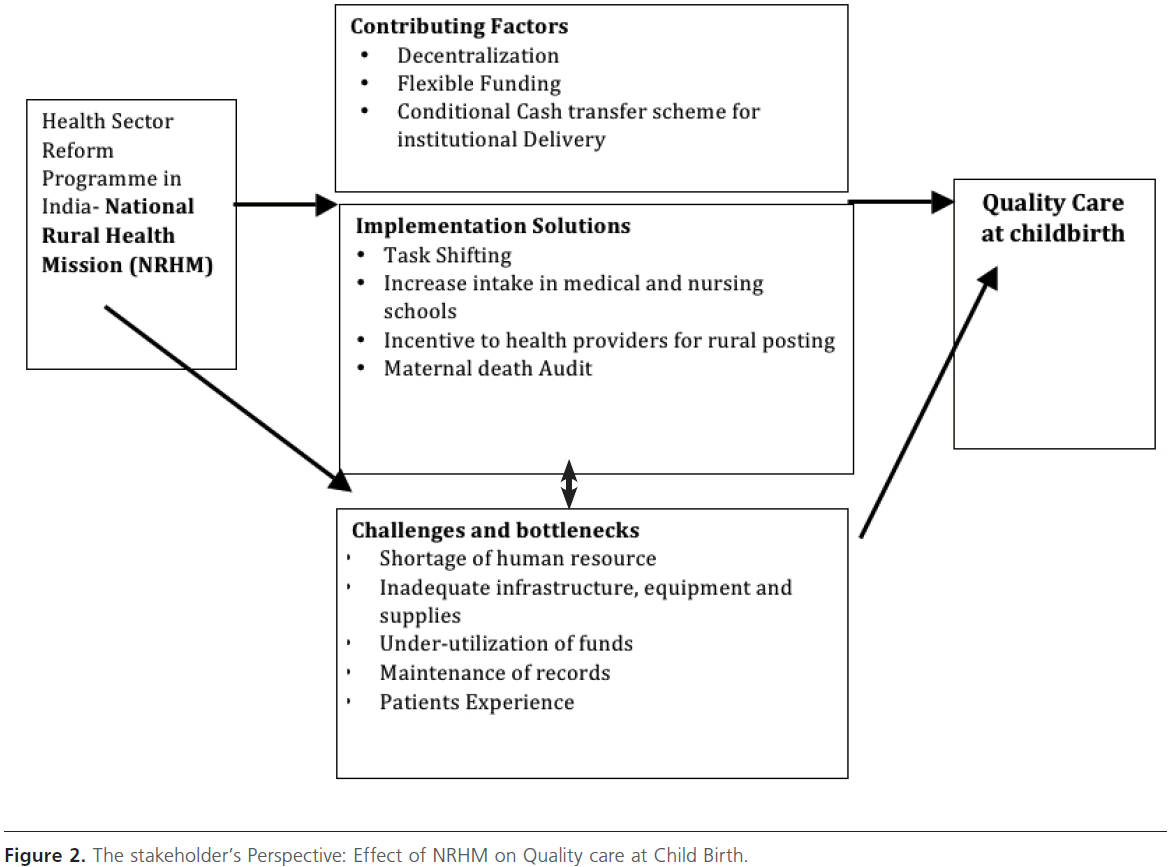

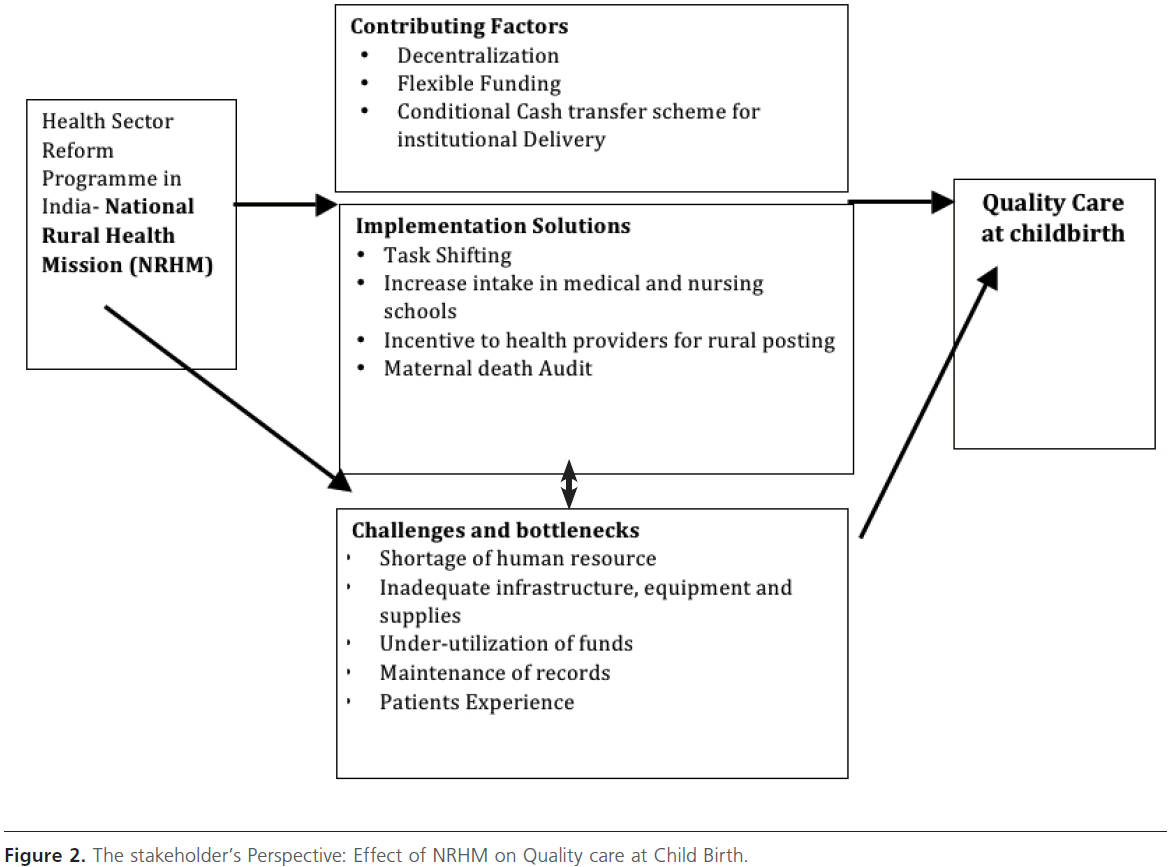

This section presents the key findings from the stakeholder interviews, relating to the changing quality of care scenario post-NRHM, and the associated challenges that need to be addressed by the states. Findings have been arranged in four sub-sections.

The current health sector reform scenario: focus on quality maternal, neonatal and child health

With the advent of NRHM in 2005 a sense of positivity regarding health policy and programming for MNCH and QOC in India has emerged as a consistent theme across all the states. NRHM is a departure from historical health planning as it “doesn’t focus on the goals but on inputs, strategies and programmes” for the “necessary architectural correction in the basic health care delivery system”. [7] As a result, while good performing states like Tamil Nadu have made appreciable advancements, the scale of progress in low performing states like Orissa and Rajasthan has been truly phenomenal compared to last few decades.

“...of course in 2000 you didn’t have a National Rural Health Mission…. it was around 2005-06 that the turning point really took place in this country... it’s not just the positive environment but it’s a very fertile environment for maternal health in India, post the launch of NRHM [...] there are policies and they are backed up by budgets”,

Senior Official, Ministry of Health Government of India

The impact of NRHM on QoC was corroborated by state and district level planners as well as NGO representatives across the various states, which is reflected in terms of increase in delivery at lower end facilities. NRHM, as described by the respondents, seemed to address several key systemic issues such as infrastructure, more budgetary allotments, decentralisation, and bringing in managers into the health system. The Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) a conditional cash transfer scheme promoting institutional delivery implemented since 2005 have brought into focus the issue the QoC at public health facilities . JSY had brought about a ‘pull factor’ that worked as a catalyst to hasten the pace of health systems development and also have highlighted the need of putting in place the protocols for quality.

“An institution that has been conducting 4 deliveries a month has now around 40 deliveries to conduct. This would mean additional seating arrangements, toilet coops, drinking water facility, many more beds, labour rooms tables are needed. This pull factor has substantially contributed for accelerating the system, but now the focus needs to be providing good care”. Senior Official, Ministry of Health, Government of India.

All respondents were unanimous in their appreciation of the JSY scheme in terms of the demand generated, however the unintended effects of JSY especially in making quality take a backseat at the facility level were also pointed out.

“More deliveries are happening and I am sure it will have impacts on maternal mortality with time…but it is like attracting people by giving money …it’s a short cut to quality, in some places quality may be deteriorating …there are evidence of over congestion, deliveries are happening on the floor, corridor etc…because there is not adequate capacity …so there may be a counter intuitive, negative impact in some places.”

Senior Academic

Contributing factors

Decentralization is the key contributing factor for giving States the onus for developing their health systems. In this respect, the state of Tamil Nadu is widely regarded as a success story in public health programming, having the advantage of an early start. Since 80’s, Tamil Nadu has adopted a “more coherent, state-owned, state-driven approach” to health policy and planning, prioritising social development and structural reform. Through a dedicated Public Health Act (and associated public health cadre), the state has focused on solutions for human resources (HR) through the empowerment of frontline Village Health Nurses (VHNs), the strategic upgrading of infrastructure and facilities, and the strengthening of the health management information system (HMIS), which includes measures for the routine monitoring of QOC. “Maternal and child health cannot be seen in isolation; for example, Tamil Nadu Medical Service Corporation is not for maternal and child health…it’s for the entire health system. Overall system strengthening is needed to have a good delivery of maternal and child health services.”

Former Director of Public Health, Tamil Nadu

In terms of human resource engagement, capacity expansion, infrastructure improvements and supplies of essential equipment, NRHM infused a new life into the starved health sector. The improvement is also visible in the states of Orissa and Rajasthan which have hitherto been performing poorly in terms of infrastructure, human resources and accessibility.

“we have recruited more people in the last 5 years than in the last five 5 year plans. One could actually calculate and say that over a lakh and a half service providers were recruited. This sort of drive in HR was not there for many years”.

Senior Official, Ministry of Health Government of India

Flexible funding under NRHM is the other key aspect and the states have taken the lead in initiatives to strengthen service delivery like operationalising the First Referral Units (FRUs) and Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (CEmONC) centres.

Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) a conditional cash transfer scheme for institutional deliveries under NRHM has lead to upgrading of lower-level facilities like the Primary Health Centers (PHC). In Tamil Nadu, institutional delivery along with CEmONC facility is now available at the PHC level also.

“Earlier 80% institutional deliveries were in District hospitals; now the figure has declined to 26%. Decentralization of institutional deliveries has taken place with functionalization of PHCs”

State Programme Manager, Tamil Nadu

Referral in Tamil Nadu has been further strengthened not only through emergency transportation, but also by providing mobile phones to different health cadres and displaying their numbers at the entrance to the PHC.

Challenges and bottlenecks

Progress has not been uniform across all states, as is evident through the contrast between Tamil Nadu and the two states of Orissa and Rajasthan, which are still grappling with inadequate human resources, infrastructure and supplies, nonutilisation of allocated funds and poor monitoring of health systems.

Human resource shortage has become all the more pertinent in the wake of increasing institutional deliveries under JSY, and is one of the key obstacles in delivering quality care. Health workers, particularly doctors, are reportedly difficult to recruit for rural postings; their retention is another major issue. Inadequate numbers of staff with poor clarity over roles and responsibilities seem to be imposed on systems that give rise to poor motivation, low morale, and lack of recognition of effort and achievement.

‘We are dealing with inadequate human resources and with the dilapidated buildings, women are lying on the floor and they are getting discharged as soon as they can”. District

Programme Manager, Orissa

With regard to infrastructure, both maintaining buildings and equipments to provide healthcare was a dominant and persistent theme in both Orissa and Rajasthan. Despite the flexibility and availability of funds under NRHM, planners are not able to configure infrastructure according to local needs. Under- utilization of allocated funds is evident in both Orissa and Rajasthan, while Tamil Nadu could readily absorb and spend allocated funds and further strengthen its service delivery.

“I notice most of the states around are not spending …it just means that their health system has suffered from quite a long tenure of underinvestment …and that is why they are not absorbing all the money “

Health Expert, Bilateral Agency

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) procedures were also frequently described as problematic as data is not maintained properly and often considered a burden, more bureaucratic than beneficial to programme implementers across the states.

“If you go to any district, no one will be able to tell you that this is the IMR or MMR rate because the reporting is not proper. If you don’t have the exact reporting about maternal deaths or infant deaths have taken place, then how can one say that we are moving in positive or the negative direction”.

District Programme Manager, Rajasthan

Patient’s experience is one of the key criteria for QOC, a challenge that was reported even in Tamil Nadu. Insensitive provider behavior at secondary and tertiary level facilities was cited as one of the main reasons why community women preferred to deliver at PHCs.

“We have developed the primary health care system but the main lacunae is in the secondary and tertiary system, so in order to make women comfortable we have introduced the birth companion system”

State Programme Manager, Tamil Nadu

Implementation solutions and lessons

In spite of the many challenges, an overall sense of positivity can be seen both in Orissa and Rajasthan in terms of delivery of quality health services. The states have devised state-specific policies to address the issue of human resources. They are also experimenting with task-shifting, which includes the training of Ayush (homeopathic) doctors in skilled birth attendance, besides increasing the seats in medical colleges, and increasing remuneration and retirement age of health personnel.

“there are 600 contractual doctors who have been recruited; 200 posts of specialists (gynecologists/anesthetists/pediatricians) were advertised recently - remuneration was increased from Rs. 40,000 to 60,000 and age bar was relaxed to 60 years to encourage retired persons to apply.”

District Programme Manager, Rajasthan

With respect to monitoring, in recent years maternal death audits have been piloted in some districts of Orissa and Rajasthan, based on the experience of Tamil Nadu.

NRHM, as described by the respondents, seemed to address several systemic issues such as infrastructure, lack of funds, promote decentralisation, bringing in managers into the health system etc. and these cumulatively had a salutary effect on MNCH outcomes across the country. However, in a country as vast and varied as India it takes time for the effects of the reforms agenda of NRHM to percolate down to the peripheral levels. This is especially the case in areas where health systems have been neglected for several decades. Many respondents, while acknowledging the reform agenda of NRHM and its impact also pointed out that it was a work in progress and the pace of reforms needed to be sustained if long term changes were needed particularly in effecting quality of care for maternal health service (Figure 2). This was captured succinctly in the words of an expert, who said:

Figure 2: The stakeholder’s Perspective: Effect of NRHM on Quality care at Child Birth.

“This is a situation where the house is not fully in order before the guests have been invited.”

Maternal Health Expert , Government of India

“Since introduction of this NRHM, things have improved… before that there was paucity of funds, manpower, infrastructure, apparatus and equipments, trainings etc., but a lot of things still need to improve.”

District Medical Officer, Rajasthan

Discussion

Developing countries like India have tested with similar reform program, which has resulted in success, like in Malaysia with the Maternal and Child health strategic plan (2006-2010) where quality forms the core, has resulted in a high rate of institutional delivery touching almost 98% (9). Similarly in Bangladesh and Nepal by upgrading and betterment of the facilities and training of the service providers in those facilities have resulted in improvement in maternal health outcome (10, 11), as in Bangladesh MMR has declined from 514 in 1986-90 to 400 in 2003, that is 22 percent in the 11 intervening years of Health, Nutrition and Population Sector Program (12).

In India the present study findings reveal an overall positive influence of NRHM in addressing health system challenges in India, which has been noted by other studies as well. A study in Rajasthan, for example, notes that renovation of physical infrastructure under NRHM has led to improved staff morale and increased patient inflow (13).Despite the positive impacts of NRHM, serious implementation issues exist. These may, at least in part, stem from health systems and health infrastructure that suffers from chronic and long term under-investment (14). Findings highlight that while NRHM is effectively tackling these bottlenecks, many challenges persist. Human resource is one such challenge, other challenges being gaps in infrastructure and supplies, and lack of supervisory and managerial efficiency. Similar challenges have been reported in other developing country settings as well. One of the biggest maternal health challenges lies in the availability, retention and training of skilled birth attendants (15). The skewed ratio often leads to overburdening of providers with clinical as well as administrative workload, thus compromising quality of care (16). Similarly on the supply side inadequate equipments, drugs, supplies like blood to the EmOC facilities and supervision remains a gap in most of the countries where MMR is still high (17,18).

Similar issues have been reported in a multi-state study in India, which reports delays in recruitment, insufficient training of community health workers, staff absenteeism and apathy of doctors posted in rural areas as key health system challenges (19). In India there is still a preference for private facilities mainly on account of good staff behavior and availability at all times, and good physical infrastructure (20). Higher level of patient dissatisfaction was also associated with staff absenteeism, lack of medicines and long waiting time (21).

Regional imbalances, however, are still persistent and NRHM has not succeeded in removing the imbalance in health infrastructure at least at the sub-centre and PHC levels, with high-focus states lagging behind in implementation as compared to more developed ones. This is a critical stakeholder observation which is corroborated by other studies as well. Patients utilizing PHC & OPD services are considerably higher in non high-focus states. A large proportion of health centres in high-focus states has not been able to spend untied funds for infrastructure up-gradation in spite of glaring shortages/ structural problems (22).

It can be reasonably concluded that the current policy and programming environment is characterized by positivity with the advent of NRHM. Not only is there increased funding, but also a tangible ‘vibrancy’ in the health system. This is reflected in innovations like the ASHAs, JSY and many other small-scale initiatives (23). Infrastructure, human resources, supplies and equipment are avenues for holistic health system policy and programming to achieve QoC for MNCH (24). The success of such efforts would, however, vary in different regional contexts. Experiences from well performing states like Tamil Nadu, which has explicitly focused on health system reform, demonstrate that in settings where public health systems have been given priority, policies and programmes can be coherently, easily and effectively implemented (25). This is also a way forward for the path to be taken by other states in their efforts towards quality MNCH.

Conclusion

In the initial phase of health system reform program in India the emphasis is on strengthening the structural aspect of care that is physical infrastructure, human resource, supplies. But the process of care which includes safety, timeliness, responsiveness and patient-centered care like respect, dignity, emotional support is crucial to get positive outcome in terms of decline in morbidity and mortality of mothers and newborns (26, 27, 28). To complete the whole quality of care cycle, equal emphasis is needed on process of care also. Current public health QOC norms in India incorporate clinical effectiveness and management, but are less clear on relatively intangible aspects like responsive and patient centred care. The focus is undoubtedly on structural elements, given the gross structural deficiencies that plague India’s health system.

1841

References

- Osman FerdousArfina. Health Policy, Programmes and System in Bangladesh : Achievements and Challenges. Sage. 2008 (cited 2011 January 2) available from https://sas.sagepub.com/content/15/2/263. full.pdf+html

- Thornton.Paul. The SAP Experience in Pakistan. Briefing paper produced for the Department for International Development by IHSD, 2000 (cited 2011 January 4) available from (https://www.dfidhealthrc. org/publications/Int_policy_aid_financing/Sapak.PDF

- Gilson L, Mills A. Health sector reforms in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons of the last 10 years. Health Policy. 1995 Apr-Jun;32(1-3):215-43.

- Sample Registration Survey Bulletin, India, Registrar General of India, 2009 (cited 2010, October 15) available https://censusindia.gov.in/ vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/Bulletins.aspx

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National Rural Health Mission. Mission Document. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The Indian Public Health Standards (cited 2010 April 2) available from https://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/iphs.htm. .

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National Rural Health Mission - Framework for implementation. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005.

- UNICEF. Maternal and perinatal death enquiry and response. Empowering communities to avert maternal deaths in India. New Delhi: UNICEF; 2009.

- Manaf NH. Quality Management in Malaysian Public Health Care, International Journal of Healthcare Quality Assurance, 2005 18(3) 204- 16.

- Mridha MK, Anwar I, Koblinsky M. Public-sector maternal health programmes and services for rural Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2009;27(2):124.

- Rath AD, Basnett I, Cole M, Subedi HN, Thomas D, Murray SF. Improving Emergency Obstetric Care in a Context of Very High Maternal Mortality: The Nepal Safer Motherhood Project 1997–2004. Reproductive Health Matters. 2007;15(30):72-80

- Koblinsky M, Anwar I, Mridha MK, Chowdhury ME, Botlero R. Reducing maternal mortality and improving maternal health: Bangladesh and MDG 5. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2009;26(3):280

- Dwivedi, H. et al. Planning and implementing a program of renovations of emergency obstetric care facilities: experiences in Rajasthan, India. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2002; 78 (3): 283-91.

- NRHM Third Common Review Mission. Draft report. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2010.

- Gerein N, Green A, Pearson S. The implications of shortages of health professionals for maternal health in sub-saharan Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14(27):40-50.

- Figo SM. Human resources for health in the low-resource world: Collaborative practice and task shifting in maternal and neonatal care. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2009

- Obaid TA. Fifteen years after the International Conference on Population and Development: What have we achieved and how do we move forward? International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;106(2):102-105.

- Islam MT, Haque YA, Waxman R, Bhuiyan AB. Implementation of emergency obstetric care training in Bangladesh: lessons learned. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14(27):61-72.

- The Indian Trust for Innovation and Social Change (ITISC). The socio-economic determinants behind infant mortality and maternal mortality. New Delhi: ITISC; 2007

- Jain M, Nandan D, Misra SK. Qualitative assessment of health seeking behaviour and perceptions regarding quality of health care services among rural community of district Agra. Indian J Community Med 2006; 31 (3): 140-44.

- Akoijam BS, Konjengbam S, Bishwalata R, Singh TA. Patients’ satisfaction with hospital care in a referral institute in Manipur. Indian J Public Health 2007; 51(4): 240-3.

- Bajpai N, Sachs JD, Dholakia RH. Improving access, service delivery and efficiency of the public health system in rural India. Mid-term evaluation of the National Rural Health Mission. CGSD working paper no. 37. The Earth Institute at Columbia University; 2009.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Four years of NRHM 2005-2009. Making a difference everywhere. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2009.

- WHO. South East Asia Regional Office. Safer pregnancy in Tamil Nadu – from vision to reality. New Delhi: World Health Organization; 2009.

- Padmanaban P, Raman PS, Mavlankar D. Innovations and challenges in reducing maternal mortality in Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 2009; 27 (2): 202-219.

- Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 1966;44:166-206.

- Institute of Medicine. Medicare – A strategy for quality assurance. Volume I. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1990.

- Hulton LA, Matthews Z, Stones RW. Applying a framework for assessing the quality of maternal health services in urban India. Social Science and Medicine 2007;64:2083-95.