Jin-Ho Lee1, Kyu-Yong Lee1,2, Hyun-Hee Park1, Eun-Hye Lee2, Na-Young Choi2, Sung Hyuk Heo3, Dae-Il Chang3, Hojin Choi1, Young Joo Lee1 and Seong-Ho Koh1,2*

1Department of Neurology, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Department of Translational Medicine, Hanyang University Graduate School of Biomedical Science and Engineering, Seoul, Korea

3Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea

*Corresponding Author:

Seong-Ho Koh

Department of Neurology, Hanyang University College of Medicine, 249-1 Guri Hospital, Gyomun-dong, Guri-Si, Gyeonggi-Do, 471-701, Korea

Tel: +82-31-560-2267

Fax: +82-31-560-2267

E-mail: ksh213@hanyang.ac.kr

Received date: January 10, 2017; Accepted date: January 23, 2017; Published date: January 27, 2017

Citation: Lee JH, Lee KY, Park HH, et al. Reduction of MMP-9 and MIF Levels is Associated with the Beneficial Effects of Cilostazol in the Patients with Silent Brain Infarcts. J Neurol Neurosci 2017, 8:1. doi: 10.21767/2171-6625.1000169

Keywords

Silent brain infarcts; Cilostazol; MMP-9; MIF

Introduction

Silent brain infarcts (SBIs) are used to describe cerebral infarcts seen on brain computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without any corresponding stroke episode [1-3]. It has been reported that the prevalence of SBIs ranges from 8% to 28% in population-based studies and that old age and hypertension are the most widely accepted risk factors for SBIs [3]. The presence of SBIs increases the risk of subsequent stroke two- to four-fold in the general population, independent of cardiovascular risk factors. The results of the Rotterdam Scan Study showed that the presence of SBIs more than doubles the risk of dementia [4-7]. Because of the clinical importance of these lesions, researchers have examined the effectiveness of antithrombotic agents in arresting the appearance or progression of SBIs in patients with diabetes or non-valvular atrial fibrillation [8-10]. In 2014, the revised AHA/ASA guideline identified silent infarction as an important and emerging issue in secondary stroke prevention [11].

Although the cause of SBIs is not fully understood, inflammation might play an important role in their development and progression as it does in acute symptomatic stroke. Several kinds of biomarkers are involved in the pathophysiology of acute infraction. For example, increased levels of active matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) has been reported to be associated with deterioration following an initial acute lacunar stroke [12]; macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is up-regulated in the brain after cerebral ischemia and is involved in neuroinflammation [13,14]; visceral fat–derived adipokine (visfatin) is also up-regulated after cerebral ischemia and is implicated in the atherosclerotic process [15,16]; chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 12 (CXCL12) is increased in the penumbra after acute stroke and thought to be a key regulator in repair of strokes [17,18]; and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is crucially involved in neurovascular remodeling especially in the acute ischemic brain [19,20].

Cilostazol, a specific cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) phosphodiesterase type III (PDE3) inhibitor has anti-inflammatory effects both in vitro and in vivo. It blocks nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kB), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathways and inhibits the immortalized murine microglial cell line BV2 [21]. It also decreases B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) protein in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and has anti-inflammatory effects in hypertensive and type 2 diabetes mellitus patients [22]. In an animal study, it inhibited the NF-kB signaling pathway in the aortas of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated rats [23]. However, these various inflammatory biomarkers are not specific for stroke [24].

In the present study, therefore, we measured a number of such inflammation- and angiogenesis-associated biomarkers after treatment for various times with cilostazol to see whether cilostazol also has beneficial effects in patients with SBIs.

Methods

Patients

This observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University Guri Hospital and was performed in the Department of Neurology. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before entry into the study. We included patients aged from 18 to 80 years registered at the Hanyang University Guri Hospital Stroke Registry between January 2012 and July 2012 and who visited the outpatient department. A total of 251 patients who had SBIs on brain MRI were recruited.

Several exclusion criteria were applied to these 251 patients: (1) a history of stroke-like symptoms; (2) signal changes on brain MRI suggestive of an acute stage of infarction or of any stage of hemorrhage; (3) any disease that might influence inflammatory markers (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, sepsis, asthma, tuberculosis, glomerulonephritis, atopic dermatitis, systemic sclerosis, multiple sclerosis) [15,16,25]; and (4) recent changes in medication regimen within the last 3 months that might influence inflammatory markers (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, and anti-hypertensive agents).

Of the 225 patients included in the registry, 187 were excluded because of stroke-like symptoms or signal changes on brain MRI suggestive of an acute stage of infarction or some stage of hemorrhage. In addition, 8 patients were excluded because of underlying disease and 4 on account of medication taken within 3 months of enrollment. Finally, 26 patients were selected for a cilostazol group (200 mg/day). A control group was also included that consisted of age and sex-matched healthy individuals without SBIs recruited from Hanyang University Guri Hospital and no vascular risk factors or history of brain vascular incidents.

Image analysis and laboratory measurements

All brain imaging studies were originally interpreted by neuroradiologists. We defined an SBI as a focal hyperintensity on T2-weighted images, 3~15 mm in size, and a hypointensity on T1-weighted images with a hyperintense rim on fluid attenuated inversion recovery images, as described previously [2,3,26,27]. Blood samples were collected at baseline, and after 1 week and 3 months, and stored at -80°C. The biomarkers MMP-9, MIF, visfatin, CXCL12, and VEGF were assessed with commercially available quantitative sandwich ELISA kits, following the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D system, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to analyze intergroup differences of categorical data. Data that did not show a normal distribution were expressed by their median and interquartile range values and compared by the Mann-Whitney test. Comparisons of inflammatory biomarkers within groups were made with the Friedman and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. The statistical software SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the analyses. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Silent brain infarcts

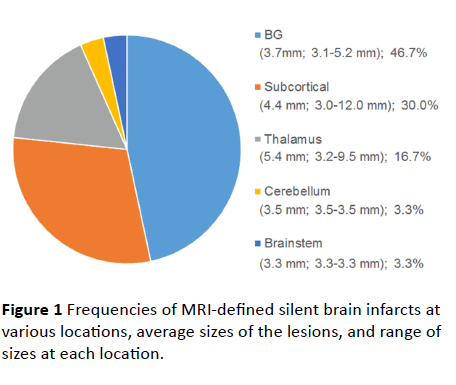

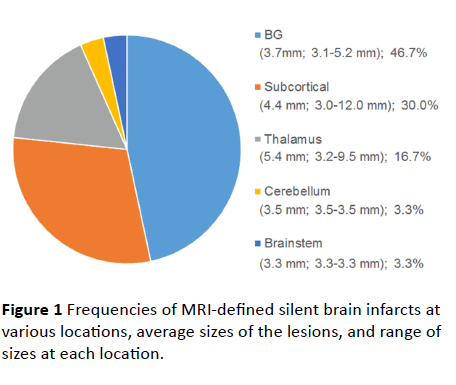

We investigated 26 subjects with SBIs on brain MRI and 10 healthy volunteers. The mean age of a total of 26 individuals was 64.7 years, and 76.9% were women. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data are summarized in Table 1. The youngest patient with an SBI was aged 41 years, and the proportion of patients who had hypertension was 30.8%. We identified a total of 30 SBIs in the 26 patients. The majority (n=22, 84.6%) had only a single lesion and 4 (15.4%) had two lesions. The SBIs were mostly located in basal ganglia (46.7%) and subcortical regions (30.0%) (Figure 1). The average SBI diameter was 4.4 mm, range 3.0 to 12.0 mm.

| |

Healthy control subjects

n=10 |

Cilostazol group

n=26 |

P value |

| Age (years) |

57.6 ± 14.3 |

64.7 ± 10.9 |

0.214 |

| Male sex (%) |

20.0 |

23.1 |

0.842 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

24.6 ± 3.1 |

24.35 ± 4.1 |

0.931 |

| Hypertension (%) |

- |

30.8 |

- |

| Diabetes (%) |

- |

19.2 |

- |

| Dyslipidemia (%) |

- |

26.9 |

- |

| Smoking (%) |

- |

3.8 |

- |

| Alcohol (%) |

- |

11.5 |

- |

| SBI (number) |

- |

1.4 ± 0.6 |

- |

| SBI (size) |

- |

4.4 ± 2.6 |

- |

| MMP-9 (ng/mL) |

28.25 ± 7.80 |

38.41 ± 7.43 |

0.002† |

| MIF (ng/mL) |

67.27 ± 43.34 |

87.24 ± 16.55 |

0.145 |

| Visfatin (ng/mL) |

1.23 ± 0.58 |

1.35 ± 1.48 |

0.497 |

| CXCL12 (pg/mL) |

1901.08 ± 151.72 |

1913.01 ± 559.08 |

0.741 |

| VEGF (pg/mL) |

75.11 ± 37.97 |

57.95 ± 30.85 |

0.126 |

Values are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD) or percentages (%).

BMI: Body Mass Index; SBI: Silent Brain Infarcts; MMP-9: Matrix Metalloproteinase-9; MIF: Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor; Visfatin: Visceral Fat–Derived Adipokine; CXCL12: C-X-C Motif Ligand 12; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor.

†P<0.05

Table 1 Demographic data, vascular risk factors, the number and size of silent brain infarcts, and baseline biomarker levels.

Figure 1 Frequencies of MRI-defined silent brain infarcts at various locations, average sizes of the lesions, and range of sizes at each location.

Changes in biomarkers after treatment

Overall, there were no significant differences between the two groups except that MMP-9 was lower in the healthy controls compared to the patients with SBIs [Healthy controls vs. SBI group: MMP-9 (28.25 ± 7.80 ng/mL vs. 38.41 ± 7.43 ng/mL; p<0.05)] at the baseline.

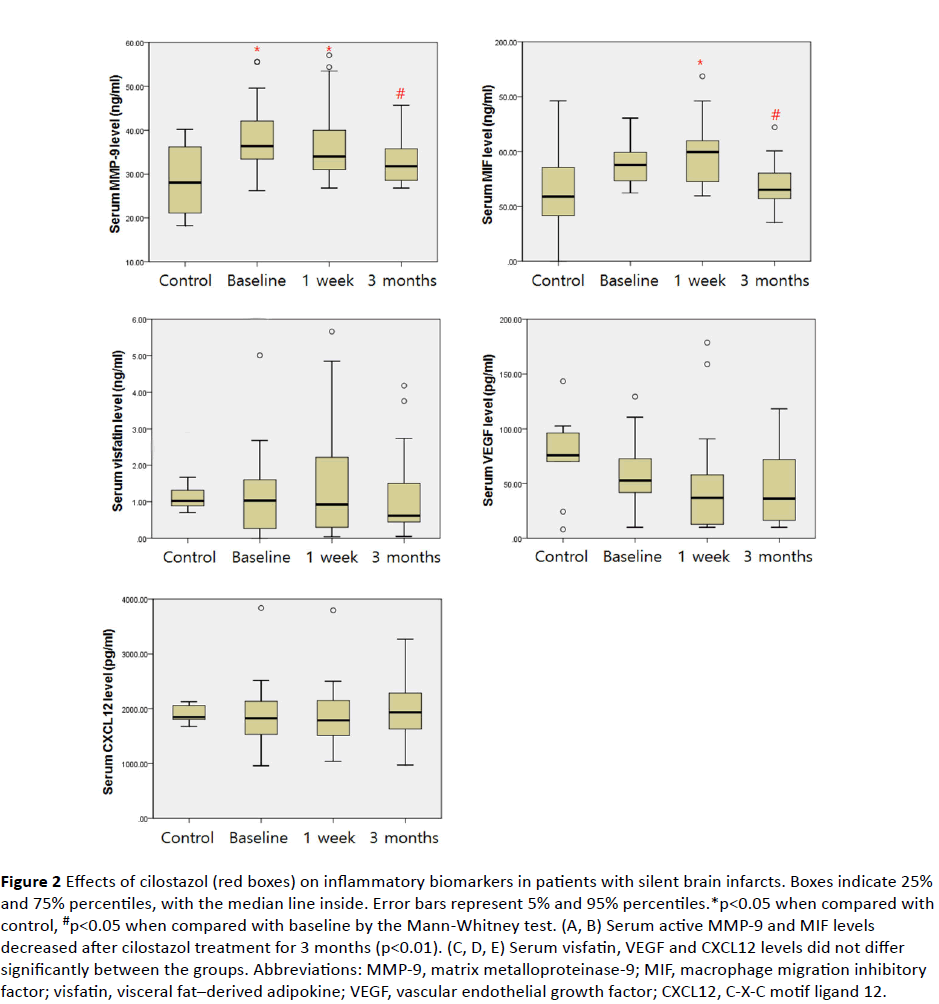

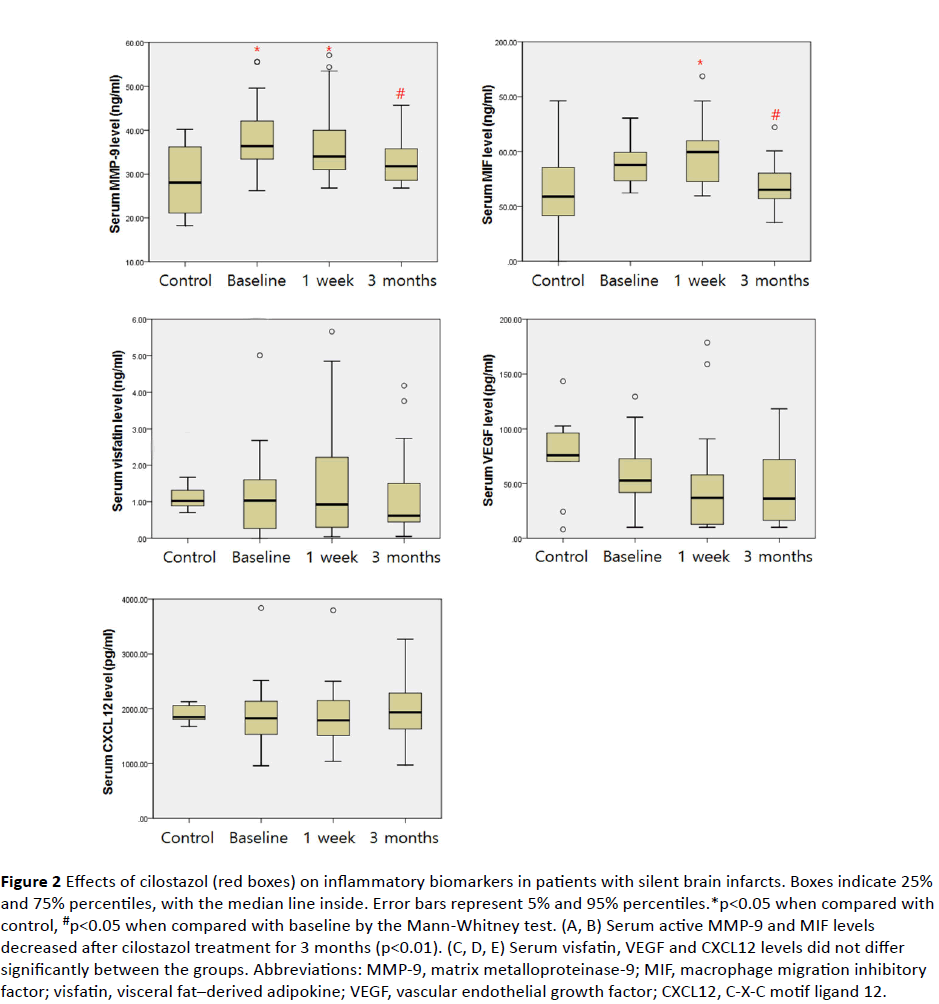

In the intragroup analysis of the cilostazol group, there were significant differences in MMP-9 and MIF levels [MMP-9 (p<0.01) and MIF (p<0.01); Friedman test] depending on the duration of the treatment. Post-hoc analysis showed that MMP-9 decreased significantly after 1 week and after 3 months of cilostazol treatment [baseline vs. 1 week vs. 3 months: MMP-9 (38.41 ± 7.43 ng/mL vs. 36.47 ± 8.36 ng/mL vs. 32.92 ± 5.18 ng/mL, respectively)], and MIF decreased after 3 months of cilostazol treatment but there was no significant difference after 1 week [baseline vs. 1 week vs. 3 months: MIF (87.24 ± 16.55 ng/mL vs. 96.28 ± 28.23 ng/mL vs. 68.90 ± 19.90 ng/mL, respectively)] (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Effects of cilostazol (red boxes) on inflammatory biomarkers in patients with silent brain infarcts. Boxes indicate 25% and 75% percentiles, with the median line inside. Error bars represent 5% and 95% percentiles.*p<0.05 when compared with control, #p<0.05 when compared with baseline by the Mann-Whitney test. (A, B) Serum active MMP-9 and MIF levels decreased after cilostazol treatment for 3 months (p<0.01). (C, D, E) Serum visfatin, VEGF and CXCL12 levels did not differ significantly between the groups. Abbreviations: MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase-9; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor; visfatin, visceral fat–derived adipokine; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; CXCL12, C-X-C motif ligand 12.

MMP-9 levels of the cilostazol group after 1 week (CSZ1w) were higher than that of the healthy controls [healthy controls vs. 1 week: MMP-9 (28.25 ± 7.80 ng/mL vs. 36.47 ± 8.36 ng/mL; p<0.05)] but there was no significant difference in the level of MMP-9 between the cilostazol group (CSZ3m) and healthy controls at 3 months [healthy controls vs. 3 months: MMP-9 (28.25 ± 7.80 ng/mL vs. 32.92 ± 5.18 ng/mL; p=0.112)].

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated 36 subjects (26 patients with SBIs and 10 controls) and 30 SBIs. Among the various inflammation- and angiogenesis-associated markers, only MMP-9 at baseline was higher in the subjects with SBIs than in the normal controls. After taking cilostazol, levels of MMP-9 and MIF were significantly reduced at 1 week and 3 months.

The cause of SBIs is not fully understood. However, mechanisms leading to lacunar stroke, including lipohyalinotic and arteriosclerotic changes, are also considered major causes of SBIs because some of the characteristics of SBIs, such as size, location, and correlation with hypertension, resemble those of lacunar infarction [3]. Various biomarkers including MMP-9, MIF, CXCL12, visfatin, and VEGF have been reported to be up-regulated after cerebral infarction [18,20,28-30]. MMP-9 is implicated in early neurologic deterioration after ischemic stroke and plays a major role in remodeling and recovery following the hyperacute stage of ischemic stroke [31,32]. Hence, it may also be a meaningful marker for SBIs. This hypothesis is supported by our finding that MMP-9 levels in subjects with SBIs were higher than in healthy controls.

In the CSZ3m (cilostazol for 3 months) group, MMP-9 and MIF declined markedly from baseline levels. On the basis of these results, it appears that cilostazol has beneficial effects, which is in agreement with previous studies [21,23,24,33,34], through reducing MMP-9 and MIF. Invasion of monocytes in the matrix of the intima depends on cleavage of the extracellular matrix by proteinases such as MMP-9, which is the most prevalent form of MMPs expressed by monocyte-macrophages. In a previous experimental study, cilostazol was shown to inhibit the invasive ability of monocytes upon differentiation toward macrophages. Inhibition of monocyte infiltration reduces recruitment of macrophages, and reduced numbers of activated macrophages results in decreased amounts of growth factor secreted [35]. In the present study, cilostazol decreased MMP-9 and MIF levels, and these findings may partly explain that cilostazol could inhibit monocyte-macrophage-induced inflammatory processes.

In addition, we found that long-term treatment with cilostazol reduced MMP-9 to normal levels. In light of a previous animal study showing that treatment with an MMP inhibitor, FN-439, 7 days after a stroke suppresses neurovascular remodeling, increases ischemic brain injury, and impairs functional recovery at 14 days, a large reduction in MMP-9 may be harmful [36]. We found a significant difference in MMP-9 levels between the CSZ1w group and healthy controls but not between the CSZ3m group and healthy controls. This means that the MMP-9-lowering effect of cilostazol is modest, and treatment with it can reduce MMP-9 to normal levels. Many investigators have suggested that up-regulation of MMP-9 after acute stroke increases infarct volume and contributes to BBB breakdown and that MMP-9 plays a major role in neurovascular injury during the acute phase and in neurovascular remodeling during the chronic phase [37-39] Our finding that MMP-9 is up-regulated in subjects with SBIs at baseline and that normal levels are re-established by cilostazol treatment suggests that subjects with SBIs are stroke-prone and that cilostazol is a safe and protective treatment for them.

There are some limitations to this study. First of all, this study was an observational study but not a randomized control study and our results were obtained from relatively small number of patients. Therefore, we could not think the results are confirmative. Nevertheless, we could suggest our results support strong tendencies about the beneficial effects of cilostazol on SBIs including anti-inflammatory effect. The second concerns MMP-9 itself; regulation of MMP-9 is complex, and its clinical effects in the different phases of stroke are far from being completely understood. Third, although we took histories diligently, and routinely performed chest X-rays, electrocardiography, and dyslipidemia, our workup may have been insufficient to rule out other causes of the SBIs, such as underlying heart disease or atherosclerosis. Also, subjects with SBIs are not strictly ‘patients with stroke’; therefore, exhaustive workups such as echocardiography, neck vessel angiography, etc. could not be justified and these patients could not be fully differentiated. The forth limitation is that the pathophysiology of SBIs is not completely understood. The last limitation is that, because this study was an observational study using serum from patients with SBIs but not an experimental one, we cannot explain the exact reason why cilostazol showed different effects on diverse inflammatory biomarkers; for example, it reduced MMP-9 and MIF but no other biomarkers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that the level of the inflammatory marker MMP-9 was elevated in patients with SBIs, adding evidence for a link between inflammation and SBIs. The beneficial effects of cilostazol in the acute and chronic phases were also demonstrated. Future studies are needed to clarify the risk-benefit profiles of cilostazol treatment for stroke.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (2015R1A2A2A04004865) and by a grant from the NanoBio R&D Program of the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2007-04717).

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

18202

References

- Masuda J, Nabika T, Notsu Y (2001) Silent stroke: Pathogenesis, genetic factors and clinical implications as a risk factor. Curr Opin Neurol 14: 77-82.

- Zhu YC, Dufouil C, Tzourio C, Chabriat H (2011) Silent brain infarcts: A review of MRI diagnostic criteria. Stroke: A journal of Cerebral Circulation 42: 1140-1145.

- Vermeer SE, Longstreth WT, Koudstaal PJ (2007) Silent brain infarcts: A systematic review. Lancet Neurol 6: 611-619.

- Vermeer SE, Den Heijer T, Koudstaal PJ, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, et al. (2003) Incidence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke 34: 392-396.

- Vermeer SE, Hollander M, Van Dijk EJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, et al. (2003) Silent brain infarcts and white matter lesions increase stroke risk in the general population: The Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke 34: 1126-1129.

- Vermeer SE, Prins ND, Den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, et al. (2003) Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med 348: 1215-1222.

- Bernick C, Kuller L, Dulberg C, Longstreth WT, Manolio T, et al. (2001) Silent MRI infarcts and the risk of future stroke: The cardiovascular health study. Neurology 57: 1222-1229.

- Sato H, Koretsune Y, Fukunami M, Kodama K, Yamada Y, et al. (2004) Aspirin attenuates the incidence of silent brain lesions in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circ J 68: 410-416.

- Nakamura T, Kawagoe Y, Matsuda T, Ueda Y, Ebihara I, et al. (2005) cerebral infarction in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Effects of antiplatelet drug dilazep dihydrochloride. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 21: 39-43.

- Shinoda TT, Yamasaki Y, Yoshida S, Kajimoto Y, Tsujino T, et al. (2002) A phosphodiesterase inhibitor, cilostazol, prevents the onset of silent brain infarction in Japanese subjects with Type II diabetes. Diabetologia 45: 188-194.

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, et al. (2014) Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45: 2160-2236.

- Koh SH, Park CY, Kim MK, Lee KY, Kim J, et al. (2011) Microbleeds and free active MMP-9 are independent risk factors for neurological deterioration in acute lacunar stroke. Eur J Neurol 18: 158-164.

- Inacio AR, Ruscher K, Leng L, Bucala R, Deierborg T (2011) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes cell death and aggravates neurologic deficits after experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab: Official Journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 31: 1093-1106.

- Wang L, Zis O, Ma G, Shan Z, Zhang X, et al. (2009) Upregulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene expression in stroke. Stroke: a Journal of Cerebral Circulation 40: 973-976.

- Lu LF, Yang SS, Wang CP, Hung WC, Yu TH, et al. (2009) Elevated visfatin/pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor plasma concentration in ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis: The Official Journal of National Stroke Association 18: 354-359.

- Filippatos TD, Randeva HS, Derdemezis CS, Elisaf MS, Mikhailidis DP (2010) Visfatin/PBEF and atherosclerosis-related diseases. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 8: 12-28.

- Hill WD, Hess DC, Martin SA, Carothers JJ, Zheng J, et al. (2004) SDF-1 (CXCL12) is upregulated in the ischemic penumbra following stroke: association with bone marrow cell homing to injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 63: 84-96.

- Schutt RC, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Mehrad B, Keeley EC (2012) Plasma CXCL12 levels as a predictor of future stroke. Stroke 43: 3382-3386.

- Hermann DM, Zechariah A (2009) Implications of vascular endothelial growth factor for post-ischemic neurovascular remodeling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab: Official Journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 29: 1620-1643.

- Ma Y, Zechariah A, Qu Y, Hermann DM (2012) Effects of vascular endothelial growth factor in ischemic stroke. J Neurosci Res 90: 1873-1882.

- Jung WK, Lee DY, Park C, Choi YH, Choi I, et al. (2010) Cilostazol is anti-inflammatory in BV2 microglial cells by inactivating nuclear factor-kappaB and inhibiting mitogen-activated protein kinases. Br J Pharmacol 159: 1274-1285.

- Kim KY, Shin HK, Choi JM, Hong KW (2002) Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis by cilostazol in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300: 709-715.

- Aoki C, Hattori Y, Tomizawa A, Jojima T, Kasai K (2010) Anti-inflammatory role of cilostazol in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and in vivo. J Atheroscler Thromb 17: 503-509.

- Agrawal NK, Maiti R, Dash D, Pandey BL (2007) Cilostazol reduces inflammatory burden and oxidative stress in hypertensive type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Pharmacol Res 56: 118-123.

- Calandra T, Roger T (2003) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a regulator of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 3: 791-800.

- Aono Y, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Hara A, Kondo T, et al. (2007) Plasma fibrinogen, ambulatory blood pressure, and silent cerebrovascular lesions: the Ohasama study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 963-968.

- Kario K, Ishikawa J, Eguchi K, Morinari M, Hoshide S, et al. (2004) Sleep pulse pressure and awake mean pressure as independent predictors for stroke in older hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens 17: 439-445.

- Wang P, Vanhoutte PM, Miao CY (2012) Visfatin and cardio-cerebro-vascular disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 59: 1-9.

- Dong X, Song YN, Liu WG, Guo XL (2009) Mmp-9, a potential target for cerebral ischemic treatment. Curr Neuropharmacol 7: 269-275.

- Lee SR, Tsuji K, Lo EH (2004) Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed neuronal damage after transient global cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci 24: 671-678.

- Kim YS, Lee KY, Koh SH, Park CY, Kim HY, et al. (2006) The role of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in early neurological worsening of acute lacunar infarction. Eur Neurol 55: 11-15.

- Ramos FM, Bellolio MF, Stead LG (2011) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 as a marker for acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 20: 47-54.

- Lee JH, Park SY, Shin HK, Kim CD, Lee WS, et al. (2008) Protective effects of cilostazol against transient focal cerebral ischemia and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion injury. CNS Neurosci Ther 14: 143-152.

- Sallustio F, Rotondo F, Di Legge S, Stanzione P (2010) Cilostazol in the management of atherosclerosis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 8: 363-372.

- Chuang SY, Yang SH, Chen TY, Pang JH (2011) Cilostazol inhibits matrix invasion and modulates the gene expressions of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells. Eur J Pharmacol 670: 419-426.

- Zhao BQ, Wang S, Kim HY, Storrie H, Rosen BR, et al. (2006) Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed cortical responses after stroke. Nature medicine 12: 441-445.

- Heo JH, Lucero J, Abumiya T, Koziol JA, Copeland BR, et al. (1999) Matrix metalloproteinases increase very early during experimental focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 19: 624-633.

- Rosell A, Ortega AA, Alvarez SJ, Fernández CI, Ribó M, et al. (2006) Increased brain expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 after ischemic and hemorrhagic human stroke. Stroke 37: 1399-1406

- Clark AW, Krekoski CA, Bou SS, Chapman KR, Edwards DR (1997) Increased gelatinase A (MMP-2) and gelatinase B (MMP-9) activities in human brain after focal ischemia. Neurosci Lett 238: 53-56.