Background & objectives: PPolycythemia in the newborn is defined as either venous hematocrit or hemoglobin levels above 65% or 22% g/dl, respectively. This study aimed to find the prevalence of polycythemia among those newborns who delivered at Duhok maternity hospital.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted from 1st June to 31st December 2019 for those newly delivered neonates at Duhok maternity hospital. The collected data were included: neonates age, sex, birth weight, gestational age, APGAR score, oxygen saturation, type of pregnancy, type of delivery, occipito-frontal circumference, and their relationships to polycythemia, in this study neonates were halved into two groups (with polycythemia and without polycythemia).

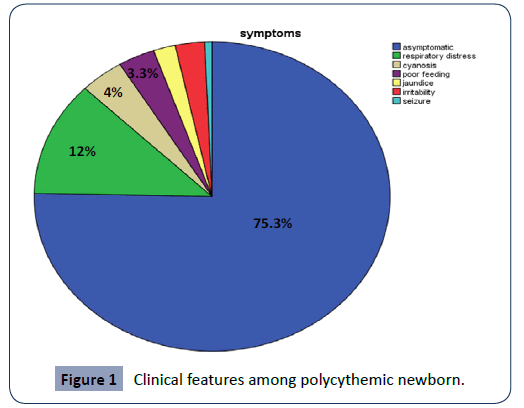

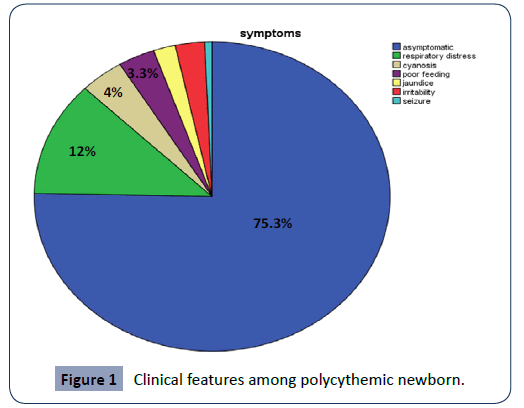

Results: Of total 300 randomly selected newborns, 31 (10.33%) had polycythemia. from those neonates; males 16 (51.6%) and females 15 (48.38%). The 2 hours or less aged babies were 18 (58.06%) and it was not significant statically from those with age more than 2 hours 13 (41.94). Polycythemia was higher among products of normal vaginal delivery 27 (87.1%) also was statistically significant. Furthermore, polycythemia was highly significant for those with gestational age 37-42 weeks 15 (48.38%), also the same among those babies with birth weight 2.5-4 kg 18 (58.08%). A 23 (74.1%) of polycythemic newborns were asymptomatic followed by respiratory distress 4 (12.9%). Cyanosis comes later with 2 (6.45%) and poor feeding 1 (3.22%).

Conclusion: Polycythemia is more prevalent among Kurdish newborns in comparison to other nationalities; most babies with polycythemia were asymptomatic followed by respiratory distress, cyanosis, and poor feeding.

Keywords

Polycythemia; Newborn; Duhok

Introduction

Polycythemia in the neonate is present when venous hematocrit is above 65% and a viscosity value >2 standard deviations greater than the normal [1,2]. The circulating red blood cell (RBC) mass, is seen frequently with abnormal elevation in newborns [3]. Its incidence is reported between 1 - 5% [1,4-6]. In newborns, Polycythemia may be a balancing mechanism for intrauterine hypoxia or secondary to fetal transfusions [7,8]. About 50% of polycythemic newborns appeared with one or more symptoms. However, symptoms mostly are non-specific and may be associated to the underlying conditions rather than due to polycythemia [7,9]. The polycythemia's risk is elevated in those born to mothers who live in high altitudes while it is lower among premature less than 34th week of gestational ages [8,10,11]. The abnormal increase in hematocrit increases the risk of hyperviscosity, microcirculatory hypoperfusion, and multisystem organ dysfunction [3]. Packed cell volume when compared to cord blood levels, hematocrit levels increase to reach at the 2nd hour of life then a plateau at 2-4 hours of life. At the age of 12 to 18 hours it return to levels of cord blood [1,11]. Therefore it is very important to consider post-natal age for screening for polycythemia. When screened at 2nd hour of life, it is incidence may reach 20% while if performed at 12 to 18 hours it may be as low as 2% [1,12]. Polycythemia is not reviewed as a benign condition; the abnormal increase in hematocrit increases the risk of hyperviscosity, microcirculatory hypoperfusion [3], and can impair oxygenation and perfusion of tissue causing damages to vital organs such as kidneys, adrenal glands, and cerebral cortex. So an early diagnosis and prompt treatment is lifesaving matter [10,11,13,14]. Maternal factors like diabetes, hypertension, cyanotic heart disease, and smoking increase the risk of polycythemia. Polycythemia is also seen in newborns of perinatal asphyxia, twin pregnancy, intra uterine growth retardation, delayed cord clamping, trisomy 13,18,21, congenital adrenal hyperplasia and thyrotoxicosis [10,11]. Most affected infants have no clinical signs of the condition [15], symptoms, when present, often appeared by two hours after birth, after fluid shifts have happened and the hematocrit is highest, onset may be delayed to the second or third day [16]. The most common presentation of polycythemia is plethora, feeding problems and hypoglycemia. Other manifestations like hypotonia, sleepiness, irritability, jitteriness, tachycardia and cyanosis may be seen in some babies [10,11]. Screening is recommended for babies who are small for gestational age, infant of diabetic mother, mono-chorionic twins and large for gestational age because of relatively increased risk of polycythemia in these babies. No further screening is needed if hematocrit <65% at 2 hours of age unless there are symptoms of polycythemia [17]. Literature analysis shows its incidence is significantly high in delayed cord clamped newborns which prevents anemia and raises iron stores; it is beneficial for newborns but it also causes sudden rise in hematocrit level which is harmful. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and risk factors of neonatal polycythemia in Duhok city to assess the frequency of polycythemia even in asymptomatic newborns in which cord clamping was delayed.

Patients & Methods

This cross sectional study was done by screening 300 randomly selected newborns delivered at Maternity Hospital in Duhok, north of Iraq during 6 months from 1st June to 31st December 2019. All polycythemic neonates were discovered incidentally by measuring hematocrit which is done together with serum bilirubin measurement in apparently jaundiced newborns. Ethical approval was approved by the Research Ethic Committee of the Directorate of Health. Polycythemia was confirmed by measuring venous hematocrit ≥65% [18]. The blood was drained into EDTA anticoagulated test tubes. All hematocrits were measured by cell counter method using (CELL-DYN emerald analyzer–09H39–01 device, France). The participants were divided into polycythemic and non-polycythemic groups. The collected data were included: age of neonates, sex, birth weight, gestational age(as assessed from maternal last menstrual period, ultrasound in the first trimester and Dubowitz examination), APGAR score, oxygen saturation, type of pregnancy, type of delivery, occipito-frontal circumference, congenital anomalies, maternal diseases, and maternal smoking. Data were analyzed by SPSS statistics computer software version 19. The statistical importance of the difference of independent samples was found by t-test. Associations between two categorical variables were searched by cross tabulation. The statistical significance of such associations was explored by Chi-square test of homogeneity and any p-value < 0.05 was regarded statistically significant.

Results

A total number of a randomly selected 300 babies born at maternity hospital in Duhok. Among of them 31 (10.33%) were polycythemic and 269 (89.67%) were non-polycythemic. Male newborns were more than females but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.547) Table (1).

Table 1 Gender distribution.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

prevalence |

p-value |

| Total babies |

300 |

31 |

10.33% |

0.547 |

| Male |

153 |

16 |

51.6% |

| Female |

147 |

15 |

48.38% |

Polycythemia was statistically not significant in those who are aging less than 2 hours from those more than 2 hours (p=0.448) Table (2).

Table 2 Age distribution.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

Prevalence |

p-value |

| Less than 2 hours |

182 |

27 |

87.1% |

0.02 |

| More than 2 hours |

118 |

4 |

12.9% |

There was a statistically significant difference between normal NVD and C/S (p=0.036) Table (3).

Table 3 Mode of delivery.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

Prevalence |

p-value |

| NVD |

217 |

27 |

87.1% |

0.036 |

| CS |

83 |

4 |

12.9% |

There was statistically significant prevalence in premature babies <37 weeks gestational age (p=0.001) Table (4).

Table 4 Gestational age distribution.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

Prevalence |

p-value |

| Less than 37 weeks |

63 |

6 |

19.35% |

0.001 |

| 37-42 weeks |

211 |

15 |

48.38% |

| More than 42 weeks |

26 |

10 |

32.25% |

Those with LBW has statistically significant high prevalence of polycythemia (p=0.009) Table (5).

Table 5 Birth weight distribution.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

Prevalence |

p-value |

| Less than 2.5 kg |

49 |

11 |

35.48% |

0.009 |

| 2.5-4 kg |

221 |

18 |

58.08% |

| More than 4 kg |

30 |

2 |

6.45% |

There was a statistically significant prevalence of polycythemia in those with less than 10th centiles for length (p=0.001) Table (6).

Table 6 Length distribution.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

Prevalence |

p-value |

| Less than 10th centile |

58 |

16 |

51.61% |

0.001 |

| 10th- 90th centile |

226 |

13 |

41.93% |

| More than 90th centile |

16 |

2 |

6.45% |

Those newborns with OFC more than 90th centile had statistically significant (p=0.012) Table (7).

Table 7 Occipito-frontal circumference OFC distribution.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

Prevalence |

P-value |

| Less than 10th centile |

60 |

12 |

38.70% |

0.012 |

| 10th- 90th centile |

229 |

17 |

54.83% |

| More than 90th centile |

11 |

2 |

6.45% |

Those with single pregnancy had statistically significant high prevalence of polycythemia (p=0.001) Table (8).

Table 8 Type of pregnancy.

| Variable |

Total no. of babies |

No. of polycythemic babies |

Prevalence |

p-value |

| Single |

288 |

23 |

74.20% |

0.001 |

| Multiple |

12 |

8 |

25.80% |

In which a majority of selected newborns were a symptomatic 75.3%, while 12% with respiratory distress, 4% cyanosis, 3.3% poor feeding (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Clinical features among polycythemic newborn.

Discussion

Ten percent of selected newborns has polycythemia which was also observed by Chalabi study (11.85%) [19], but it's higher in comparison with Reisner and Shohat [20] (2%) and much lower incidence had been reported by Mohan (2.28%) [21], some others like Krishnan and Rahim reported somewhat high incidence an incidence of (5.8%, 5.19%) respectively [13,21]. While comparing these results to others seems to be higher may be due to different screening techniques, sample sites (capillary versus peripheral or central venous), mode of delivery, methodology of measuring (coulter counter or centrifuged capillary blood) and sample timing. This compatible result with Chalabi, study may be due to racial relation because both studies were done in Iraqi Kurdish region where most the people are of Kurdish ethnicity, may be due to high attitude geographically, same racial ethnicity, genetic and environmental factors [19]. Significant correlation was found between polycythemia and age of newborns, which was also observed by Shohat [20]. Those babies of cesarean deliveries were at lower risk for polycythemia in comparison to those born by NVD which was also reported by Abbas [9]. There was no significant gender difference as risk factor for polycythemia (male 51.61% and female 48.37%), while Mohan found more females than males [21]. Both small for gestational age and large for gestational age newborns had high incidence in comparison to appropriate for gestational age and significant incidence for those >42 weeks gestational age. This was observed by Hajduczenia [22], Jahazi and by de Waal [23,24]. Premature and postdates newborns were at high risk of developing polycythemia (19.35%, 32.25%) respectively, which was also documented by Abbas [9]. The majority of polycythemic newborns were asymptomatic (75.3%) followed by respiratory distress (12%) cyanosis (4%) poor feeding (3.3%) while Mohan found that the most common presentation was lethargy (61.30%) poor feeding and plethora by (38.70%) cyanosis (22.60%) icterus (19.30%) tachypnea (6.50%) and convulsion (3.20%). Also it wasn't in agreement with Chalabi study who found jaundice (26.4%) [13] jitteriness (20.7%) [16], plethora (13.2%) [25] and respiratory distress (13.2%) [25]. There was partial agreement with study by Singh, who showed lethargy, respiratory distress and jitteriness (11.1%, 14.8%, 25.9%) respectively [26].

Finally, this study will aware pediatrician/obstetrician about most common clinical presentation of polycythemia which will further enable us to intervene earlier to save babies from detrimental effects of hyper viscosity and this will let to know as if delayed clamping should be done or not and will determine various presentations of polycythemia.

Conclusion

Polycythemia is more prevalent among Kurdish newborns in comparison to other nationalities. This study showed neonatal risk factors for polycythemia are who are products of NVD, postdates, and those products of twin pregnancy but with no gender differences. Most babies with polycythemia were asymptomatic followed by respiratory distress, cyanosis and poor feeding.

32733

References

- Sarıcı SU, Ozcan M, Altun D (2016) Neonatal Polycythemia: A Review. Clin Med Rev Case Rep 3: 142.

- Sarkar S, Rosenkrantz TS (2008) Neonatal polycythemia and hyperviscosity. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 13: 248-255.

- Remon JI, Raghavan A, Maheshwari A (2011) Polycythemia in the Newborn. NeoReviews 12: e20-e28.

- Dempsey EM, Barrington K (2006) Short and long term outcomes following partial exchange transfusion in the polycythaemic newborn: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 91: F2-6.

- Bashir BA, Othman SA (2019) Neonatal polycythaemia. Sudan J Paediatr 19: 81-83.

- Black LV, Maheshwari A (2009) Disorders of the feto-maternal unit: hematologic manifestations in the fetus and neonate. Semin Perinatol 33: 12-19.

- Cloherty JP, Eichenwald EC, Stark AR (2012) Manual of neonatal care (7thEds). Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams.

- Rosenkrantz TS (2003) Polycythemia and hyper viscosity in the newborn. Semin Thromb Hemost 29: 515-527.

- Abbas SS, Fayadh HF (2013) Neonatal polycythemia: Risk factors, clinical manifestation and treatment applied. Iraqi J Sci 12: 390-395.

- Mostefa AM (2015) A study of prevalence and risk factors of polycythemia in neonatal nursery in Duhok. Isra Medical Journal 10.

- Hussain F, Zaheer A, Mahmood CA, Ali AS, Tahir F (2014) Frequency and related clinical features of polycythemia in full term newborns in whom cord clamping was delayed. Pak J of Med and Health Sci 8: 591-594.

- Mimouni FB, Merlob P, Dollberg S, Mandel D, Israeli Neonatal Association (2011) Neonatal polycythaemia: critical review and a consensus statement of the Israeli Neonatology Association. Acta Paediat 100: 1290-1296.

- Schimmel MS, Bromiker R, Soll RF (2004) Neonatal polycythemia: is partial exchange transfusion justified? Clin Perinatol 31: 545-543.

- Uslu S, Ozdemir H, Bulbul A, Comert S, Can E, et al. (2011) The evaluation of polycythemic newborns: efficacy of partial exchange transfusion. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med 24: 1492-1497.

- Matthews DC, Glader B (2012) Erythrocyte disorders in infancy. In: Avery's Diseases of the Newborn.

- Sankar MJ, Agarwal R, Deorari A, Paul VK (2010) Management of polycythemia in neonates. Indian Journal of Pediatr 77: 1117-1121.

- Altaf S, Choudhary HA, Jabbar N, Zeeshan B, Akram Z (2018) Effect of delayed versus early cord clamping on hemoglobin level of neonates born to anemic mothers. Am J Res Med Sci 3.

- Alsafadi TR, Hashmi SM, Youssef HA, Suliman AK, Abbas HA, et al. (2014) Polycythemia in neonatal intensive care unit, risk factors, symptoms, pattern, and management controversy. J Clin Neonatal 3: 93-98.

- Chalabi DA, Zangana KO (2018) Neonatal Polycythemia, Presentations and Associations: A Case Control Study. Journal of Kurdistan Board of Medical Specialties 4.

- Shohat M, Merlob P, Reisner SH (1984) Neonatal polycythemia: I. Early diagnosis and incidence relating to time of sampling. Pediatr 73: 7-10.

- Mohan BK (2006) A study of Neonatal Polycythemia in JSS Hospital, Mysore.

- Hajduczenia MA, Jaremba OS, Szymankiewicz M (2010) Polycythemia of the newborn. Arch Perinat Med 16: 127-133.

- Jahazi A, Kordi M, Mirbehbahani NB, Mazloom SR (2008) The effect of early and late umbilical cord clamping on neonatal hematocrit. J Perinatol 28: 523-525.

- de Waal KA, Baerts W, Offringa M (2006) Systematic review of the optimal fluid for dilutional exchange transfusion in neonatal polycythaemia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 91: F7-F10.

- Jeevasankar M, Agarwal R, Chawla D, Paul VK, Deorari AK (2008) Polycythemia in the newborn. The Indian J Pediatr 75: 68.

- Singh M, Singhal PK, Paul VK, Deorari AK, Sundaram KR (1990) Polycythemia in the newborn: do asymptomatic babies need exchange transfusion? Indian Pediatr 27:61-65.