Keywords

Ebola outbreak; Liberia; Resilient health system; Recovery; Lessons learned; Investment plan

Abbreviations

DHIS2: District Health Information System 2; EVD: Ebola Virus Disease; HDI: Human Development Index; HR: Human resources; HMIS; Health Management Information System; IDSR: Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response; IHR: International Health Regulations; ICT: Information and Communications Technology; IMS; Incident Management System; MDGs: Millennium Development Goals; MoH: Ministry of Health; MOF: Ministry of Finance: MFDP: Ministry of Finance and Development Planning; NGO: Non-governmental Organization; SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals; UHC: Universal Health Coverage; WHO: World Health Organization.

Introduction

Disease outbreaks, conflicts and other development challenges pose serious threats to fragile health systems. They easily become overwhelmed when major health emergencies occur. Consequently, enormous international resources may be mobilized to save lives but as the emergency response resources wane at the end of the acute crisis phase, the health system is quite often left with the same or additional vulnerabilities. Emergency response efforts in such settings seldom set the stage for a better and more resilient health system compared to the pre-disaster situation [1,2]. The ethical expectation would have been that emergency response efforts lead to a stronger and resilient health system that is not overwhelmed by shocks, but is able to continue to effectively provide services to the population at all times and improve health outcomes [3-6]. A resilient health system has been defined as one that has the ability to absorb disturbances or shocks, to adapt and respond with the provision of needed services [7]. Liberia is one of the three countries in West Africa that was devastated by the biggest Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in global history. Between 2014 and 2015 Liberia recorded 10,675 cases including 4,809 deaths (0.1% of total population) [8]. Among health workers, 378 cases were recorded including 192 deaths (1.8% of total health workforce) [9]. At the peak of the outbreak, health facilities were temporarily shut down due to fear and panic among health workers and the communities. The concerted efforts and collaboration between the Government of Liberia, the International community and development partners led to the interruption of EVD transmission and the country was declared Ebola free for the first time on May 09, 2015. Subsequently, the country experienced two localized outbreaks from re-emergence of Ebola cases culminating in further Ebola-free declarations by WHO on September 03, 2015 and January 14, 2016, respectively. A third flare up occurred following importation from Guinea in April 2016. The national rapid response capacity acquired over time from the onset of the outbreak in March 2014, was promptly mobilized to stop all three Ebola flare- ups successfully with only a few cases recorded in each. By the end of 2014, as the EVD transmission and number of new cases significantly declined, the Ministry of Health (MoH) led a process involving all key stakeholders to develop the Investment Plan for building a resilient health system in Liberia, 2015- 2021. The plan articulated government’s priorities in building a resilient health system that is capable of providing essential health services to the population, guaranty health security and improved health outcomes. This paper describes the experience of Liberia in developing an investment plan for building a resilient health system following the 2014-15 Ebola crisis, the approaches and realignments that were undertaken, the lessons learned and recommendations on the way forward. This could provide veritable and useful information for countries recovering from crises, on how to manage their health system recovery efforts.

Context Context

Overview of the health system

Liberia is a post-conflict setting as a result of a 14-year civil conflict (1989-2003) that devastated the health system [10]. The several years of destruction, neglect and lack of investment in the health system left the health infrastructure in poor condition, with gross shortages of skilled health workers and early warning systems were dysfunctional. The government began a health sector reform process that was aimed at rebuilding the health system in order to improve coverage and access to basic health services for the Liberian population. The first post-war National Health Policy and Plan, 2007-2011 introduced the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) that specified the minimum package of services that should be provided at every level of care, as well as the minimum resources in terms of equipment and supplies, infrastructure and workforce that are required to deliver the services [11]. This package was expanded as the Essential Package of Health Services (EHPS) that was later introduced under the current ten-year National Health policy and Plan (2011-2021) [12].

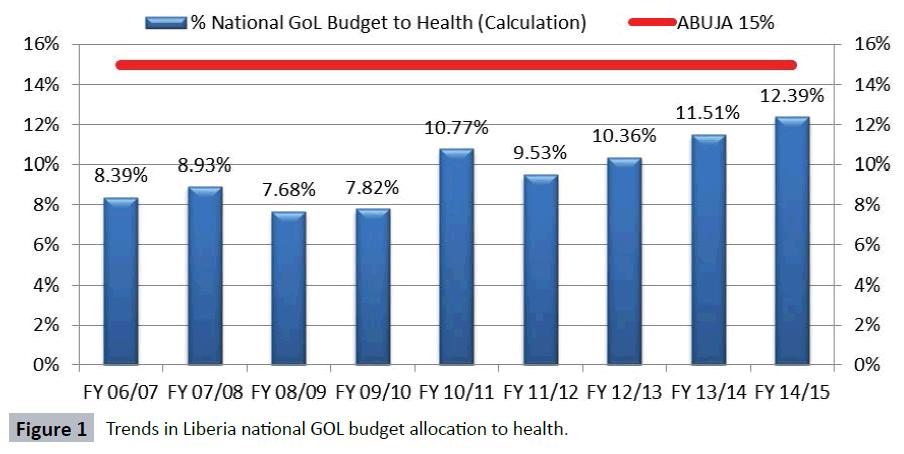

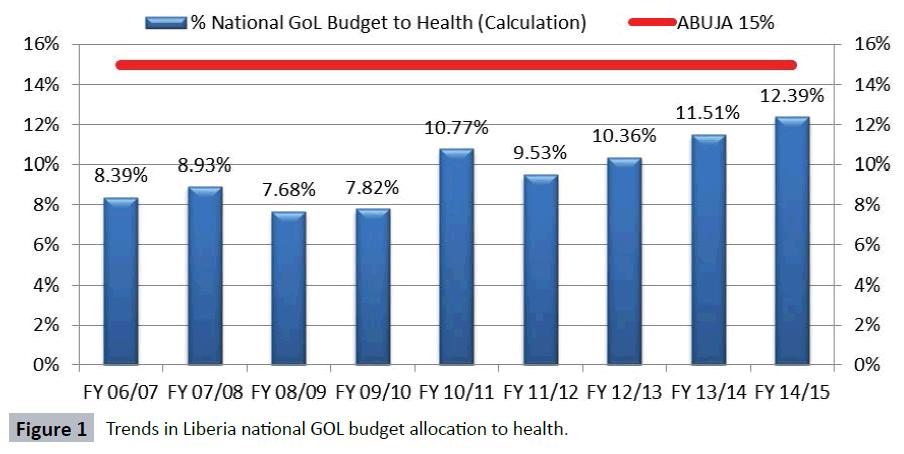

The delivery of health services takes place at three levels in Liberia; the primary level consists of the health clinics and health centres, the secondary level comprise the county and regional hospitals and the tertiary level is the John F. Kennedy Hospital located in Monrovia. Forty percent of the health facilities are of private ownership while sixty percent are public health facilities owned by government [12]. The annual investment of the government of $50-60 million in the health sector exceeded the Abuja target of 15% of the Government’s annual budget, [13] but in absolute terms under-funded the health sector that required an investment of over $200 million for the 2013/2014 fiscal year (Figure 1) [14].

Figure 1: Trends in Liberia national GOL budget allocation to health.

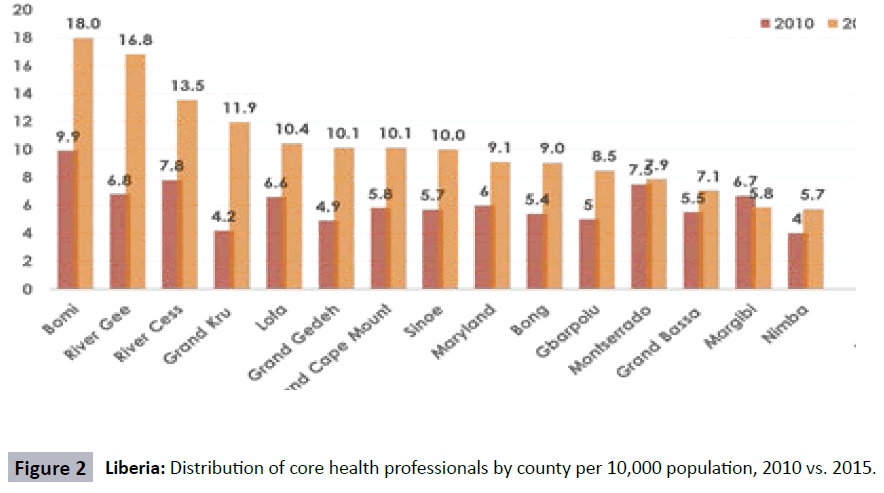

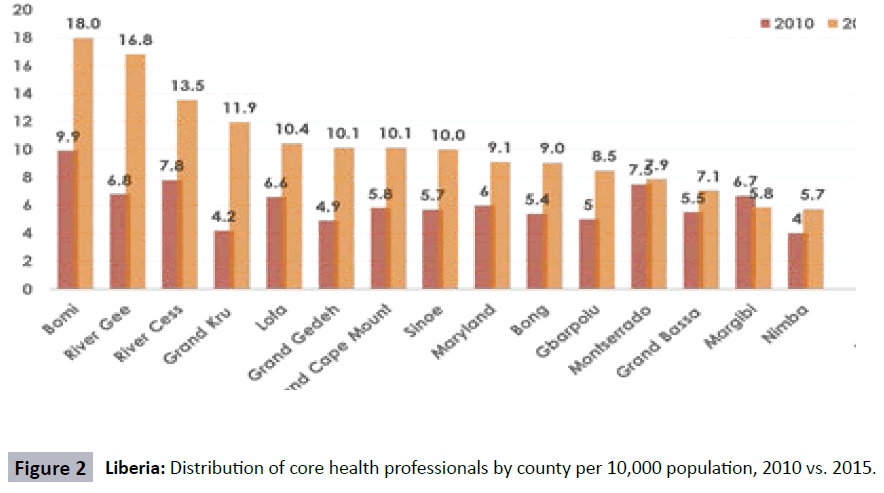

Out-of-pocket expenditure including payment of user fees in public health facilities is the predominant method of health financing. There is a general shortage of skilled health workers who are not equitably distributed thus leaving a vast proportion of the rural population under-served [15]. Health workforce crisis persists despite 37% increase in core health professionals (Doctors, Nurses, Midwives and Physician Assistants) from 6.3 per 10,000 population in 2010 to 8.6 per 10,000 population in 2015, and due to persistent inequity in the distribution of health workers (Figure 2). Health facilities experienced frequent stockout of medical supplies and the supply chain management was dysfunctional and fragmented [15].

Figure 2: Liberia: Distribution of core health professionals by county per 10,000 population, 2010 vs. 2015.

Underlying health system vulnerabilities before the EVD outbreak

As a result of a period of under-investment in the health sector, there were pre-existing fragilities in the health system that led to and aggravated EVD transmission in Liberia. These could be summarized into:

1) Inadequate inputs needed for provision of services. There were shortages of essential health workers, medical supplies and health infrastructure, with available investments inadequate to respond to the then health needs. Pre-Ebola, only 71% of the population lived within 5 km of a public health facility. The system was therefore already overstretched.

2) There were challenges with adhering to quality of care standards, with frequent complaints of dissatisfaction with experiences in utilizing services and limited peoplecentered approach in care provision.

3) There had been no previous experience of stress to the health system, to guide contingency actions. Previous epidemics had largely been limited in severity and/or scope and the epidemic preparedness, surveillance and response capacities were not effectively built.

As a result, there were deficiencies in the utilization of the existing health services especially among the rural populations, with low confidence in the services amongst the general population. Consequently, the health-related MDGs on reducing child and maternal mortality between 1990-2013 were not fully achieved [16]. Liberia’s Human Development Index (HDI) ranking (a composite measure of the population’s general well-being) of 0.388 in 2013 is lower than the sub-Saharan Africa regional average of 0.475 [17].

Impact of the EVD outbreak

The EVD outbreak impacted significantly on the delivery of health services. The spread of Ebola in health care settings impeded community confidence in the health system and a decline in the demand for services. Basic health services such as immunization, antenatal care and delivery services were interrupted as most of the health workers were mobilized to the Ebola response efforts and many also fled out of fear leaving many health facilities without staff and shut down, and others were infected with Ebola and died.

The international community mobilized enormous resources to Liberia for Ebola outbreak response. Critical to stopping the outbreak was the surge in human resource deployments, establishment of several Ebola treatment centres and mobile laboratories which gave a boost to rapid isolation, confirmation of diagnosis and treatment of Ebola cases.

Description of the recovery response

With the progressive decline in the number of cases of Ebola in Nov 2014, the government of Liberia initiated and led the planning process of developing a post-Ebola health recovery and health system resilient building plan. While it was not fully mapped out at the beginning, it eventually could be described as having happened in three phases:

Phase 1: Building the high level political and technical consensus around a common recovery strategic approach.

Phase 2: Developing the technical elements of the recovery strategic approach.

Phase 3: Building the legitimacy of the common recovery strategic approach.

Each of these phases took approximately 3 months. Phase 1 was critical as there were many actors focusing on different elements of the EVD response. It commenced when the outbreak started showing epidemiological signs of waning. While there was no formal start point, a December 2014 highlevel meeting on building resilient health systems across the Ebola-affected countries could be perceived as a starting point for this. The meeting highlighted the need to build the capacities at sub-national levels within the countries to ensure that they are sufficiently resilient and capable of responding effectively to any future public health threat [18]. Following participation at the meeting, the MoH organized a national stakeholders’ consultative meeting in-country to initiate dialogues among key stakeholders on what the strategies and priorities should be towards achieving a consensus. This consultative meeting was aimed at sharing the MoH vision of the recovery effort, and involved all the key actors in the EVD response – whether they were part of the recovery or not. In the end, all actors agreed on the need to have a clear concise strategy to guide recovery of the health system, taking cognizance of the existing resources and how to use these.

Phase 2 commenced after this consensus had been reached. Two main coordination mechanisms were adopted under the Ministry of health’s leadership, first, a core team of technical experts drawn from the Ministry of Health and key development partners. Secondly, thematic working groups were established to align with the six building blocks of the health system namely leadership/governance, health care financing, health workforce; health information system and research/epidemic preparedness, surveillance and response; service delivery; essential medicines and supply chain management. A senior staff of the Ministry of Health headed each thematic working group which drew membership from the MoH and a wide range of partners including non-health sector members. Many actors wanted to be a part of this for various reasons. However, the MoH maintained control over the process, and selected partners involvement not based on their need but on their perceived capacity to contribute to different elements of the process. While this caused some consternation in some partners, it allowed the process to proceed based on needs on the ground, and not partners’ interests. Frequent updates of the process were provided to the national Cabinet for two reasons:

i. To ensure the head of State, who was directly coordinating the response, was fully aware of the recovery plan and efforts being undertaken, and

ii. To pre-empt any lobbying by actors attempting to force actions on the country

Situation analysis

The situation analysis was taken as an opportunity to relook at the health sector strategic plan in some form of mid-term review. The working groups conducted desk reviews of various documents on previous Health System Assessments, Reviews, Policy Reforms as well as reports of various surveys, annual and progress reports of the health sector between 2007 to 2014; quantitative data were collected and narrative reports on the findings were systematically documented on formats provided. Furthermore, field assessments in the counties were undertaken and key informant interviews were conducted with selected thematic working group leaders, County Health Officers, members of the Senior Management team of the Ministry of Health to obtain clarity on the reasons why decisions were made and how they were implemented. The working groups synthesized the findings of the situation analysis and working together with a national consultant drafted the situation analysis report. At each stage, the reports from the working groups were tabled to Senior Management for review and endorsement.

Identifying key health system investment priorities and interventions

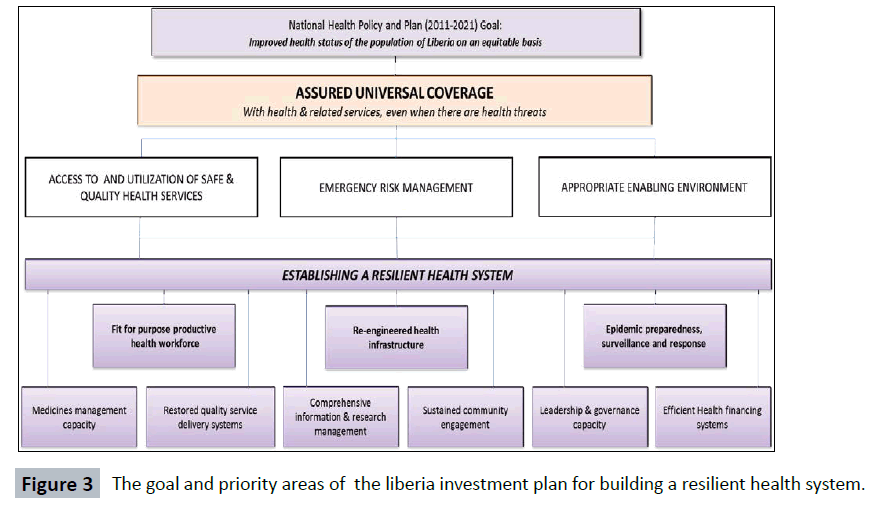

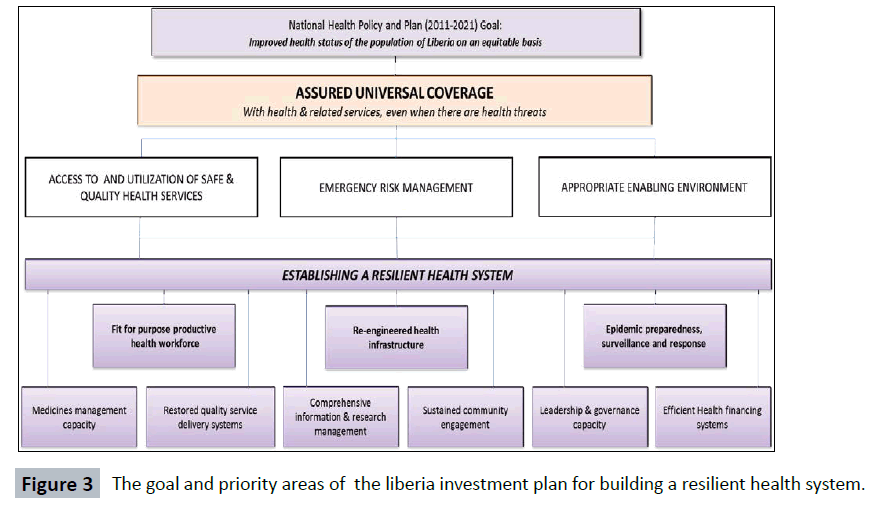

The situation analysis identified and prioritized the vulnerabilities in the health system and identified nine priority investment areas of which three were identified as the “big ticket” priorities to be implemented in the first two years and contribute to the overall goal and objectives of the investment plan. The first of the big ticket priorities was the health workforce because of the shortage of essential health workers across the country needed to provide quality basic health services and effectively respond to outbreaks. The second was health infrastructure due to the lack of health infrastructure including isolation, infection prevention and control facilities to provide emergency health services for Ebola cases and other infectious diseases. The third was epidemic preparedness, surveillance and response due to the weak early warning, surveillance and response systems for early detection and response to future disease and other public health threats. The six additional priority areas selected for the investment plan included essential medicines and supply chain management capacity; quality health service delivery systems; comprehensive health information and research management; sustained community engagement; leadership and governance capacity; and efficient health financing systems (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The goal and priority areas of the liberia investment plan for building a resilient health system.

Drafting, resource mapping and endorsement

The process of drafting the plan was a protracted, inclusive and consultative process through the constituencies of the various working groups, regular consultation with Senior Management of the Ministry of Health, the Minister of Finance and Development Planning and national stakeholder consultation workshop on the draft plan. These iterative processes led to refining of the plan. The Ministry of Health, working with the development partners, carried out extensive analysis and costing of the plan including fiscal space analysis, mapping of partners and available resources before the final editing and drafting of the plan. The final draft plan was reviewed by stakeholders at a national consensus building and validation workshop in April 2015 where further inputs and feedback were incorporated before the final endorsement of the plan by the MOH Senior Management Team, the cabinet and the Presidency by May 2015 (Table 1).

| Public health specialists |

| Policy makers and programme managers within Ministry of Health |

| Representatives of relevant line ministries and public agencies |

| Technical representatives of UN agencies and Bilateral agencies |

| Representatives of international non-governmental organizations |

| Private sector service providers |

| Local NGOs and faith-based organizations |

| Community representatives |

| The senate health committee |

| Presidential task force on Ebola |

Table 1: Stakeholders involved in the development of the investment plan.

Strengthening data collection and use

Key strategies and actions aimed at improving data collection, analysis and use for programme orientation and informing policy were incorporated into the Plan. This includes strengthening and harmonizing data collection systems, building capacities for information and data management and establishing adequate systems for sector information dissemination and use to improve health system performance.

Indicators for monitoring implementation of the plan

Key indicators derived from the national health plan (2011- 2021) were selected for use to monitor the achievement of the nine investment priorities (Table 2). The common platform for collecting information and reporting on the indicators was agreed to be the HMIS using the DHIS2 tool. This would avoid multiple and fragmented data collection and reporting by different partners.

| Domain |

Description / area |

Indicators |

Baseline |

Target (2021) |

| Goal |

Improved health status of the Liberian population |

Neonatal mortality rate per 1000 live births

Infant Mortality Rate per 1000 live births

Under-5 mortality rate per 1000 live births

Maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births |

38

54

94

1072 |

19

22

57

497 |

| Purpose |

Build a resilient health system through improved

-Access to safe and quality services

-Health emergency risk management

-Enabling environment and restoring trust |

Percentage of infants fully immunized |

65 |

91 |

| Percentage of pregnant mothers attending 4 ANC visits |

54.4 |

85 |

| Percentage of deliveries attended by skilled personnel |

61 |

80 |

| Percentage of pregnant mothers receiving IPT-2 |

48 |

80 |

| TB case detection rate (all forms) |

56 |

85 |

| Total Couple Years Protection (all methods) |

71,714 |

|

| HIV positive pregnant women who received antiretroviral treatment |

42 |

80 |

| Percentage of new/re-emerging health events responded to within 48 hours as per IHR requirements |

0 |

100 |

| Outputs per investment area |

Health workforce |

Skilled health workforce (physicians, nurses, midwives, physician assistants) per 10,000 persons |

8.6 |

14 |

| Health infrastructure |

Percentage of population living within 5 km from the nearest health facility |

71 |

85 |

| Functional health facilities per 10,000 persons |

1.63 |

2 |

| Percentage of health facilities with all utilities, ready to provide services (water, electricity) |

55 |

100 |

| Epidemic preparedness, surveillance and response system |

Percentage of counties with funded outbreak preparedness and response plans |

0 |

100 |

| Proportion of counties reporting information using event-based surveillance |

0 |

80 |

| Proportion of counties with Public health risks and resources mapped |

0 |

80 |

| Medical supplies and diagnostics |

Percentage of health facilities with no stock-outs of tracer drugs during a given period (amoxicillin, cotrimoxazole, paracetamol, ORS, iron folate, ACT, FP commodity) |

62.3 |

95 |

| Quality service delivery systems |

Number of blood units collected |

836 |

100,000 |

| Percentage of facilities practicing IPC according to standards |

65 |

100 |

| Percentage of facilities reaching two star level in accreditation survey, including clinical standards |

9.3 |

90 |

| OPD consultations per inhabitant per year |

1.9 |

2 |

| Information and communication management |

Percentage of timely, accurate and complete HIS reports submitted to MOH during the year |

36 |

90 |

| Percentage of counties with harmonized data collection systems (HMIS with LMIS, FMIS, iHRIS, CBIS) |

45 |

100 |

| Community engagement |

Percentage of communities with 2 / more general community health volunteers |

28 |

80 |

| Proportion of communities with functional community health committees |

25 |

100 |

| Leadership and governance |

Proportion of county health teams fully established and functional |

65 |

100 |

| Counties with functional stakeholders forums (County health boards) |

0 |

8 |

| Percent of bilateral aid that is untied |

25 |

80 |

| Health financing systems |

Per capita public health expenditure (US$) |

65 |

80 |

| Public expenditure in health as % of total public expenditure |

12.3 |

20 |

| Out of pocket payment for health as a share of current expenditure on health |

51 |

15 |

Abbreviations: AR (Annual Report); ARR (Annual Review Report); HFU (Health Financing Unit); H/SA (Health System Assessment Report)

Source: MOH Liberia. Targets are from the National Health Plan, unless indicator is missing, or had no target.

Table 2: Performance indicators and targets for monitoring investment implications.

Financial resource needs

The total cost estimates based on the prevailing conditions of the plan are shown in Table 3. A total investment of $1.7 billion is needed for the seven years duration of the plan, and the funding gap was estimated to be $735 million. This indicative cost represents the financial resources required to implement all of the interventions in the plan. The costing comprises capital, recurrent and operational costs needed as additional investment to complement the national health sector plan 2011-2021. The costing elements were derived after due consultation with relevant government ministries and agencies with the support of development partners. Recognizing that all the funding needed may not be available, planned activities were prioritized into three scenarios namely the best case (scenario 1), moderate (scenario 2) and baseline (scenario 3), and costed accordingly [14]. Phase 2 therefore ended with the health sector in possession of a draft that had broad consensus within Government organs.

| Investment Priority |

Total (USD)-Best Scenario1 |

Scenario 2 Moderate |

Scenario 3 Baseline |

| Fit for purpose productive & motivated health workforce |

51,05,84,494 |

53,22,70,680 |

31,94,99,983 |

| Re-engineered health infrastructure |

38,71,35,834 |

39,53,77,816 |

7,36,83,489 |

| Epidemic preparedness and response system |

9,69,63,780 |

8,60,31,362 |

2,86,55,694 |

| Management capacity for medical supplies and diagnostics |

20,91,41,641 |

19,27,97,654 |

20,60,88,880 |

| Enhancement of quality service delivery systems |

40,69,62,200 |

21,28,60,598 |

40,03,09,723 |

| Comprehensive Information, research and communication management |

59,57,617 |

57,52,653 |

54,80,564 |

| Sustainable community engagement |

3,42,57,346 |

3,98,29,632 |

64,20,075 |

| Leadership and governance capacity |

1,58,31,980 |

1,69,22,557 |

64,91,160 |

| Efficient health financing systems |

3,68,13,067 |

3,69,12,110 |

1,22,55,584 |

| Total cost |

1,703,647, 959 |

1,51,87,55,063 |

1,05,88,85,153 |

| GOL/Domestic Financing |

41,68,96,907 |

|

|

| Donor Financing |

55,17,87,821 |

|

|

| Total Funds Mapped/Projected |

96,86,84,728 |

|

|

| GAP/Financing Source TBC |

73,49,63,231 |

|

|

Table 3: Total cost estimates for implementing Liberia’s complete investment plan, 2015-2021.

Phase 3 focused on institutionalizing the recovery strategic actions. This focused on various methods to engage possible sources of funding, to discuss rationale and expectations of the different priorities highlighted in the plan, together with implications of not addressing them. Direct discussions were held in country with key potential sources of financing such as the USAID, CDC, UNICEF, and other donors. In addition, the priority elements of the recovery strategy were included in the joint recovery plan for the three EVD most affected countries and presented for funding at donor conferences. All efforts at resource mobilization were therefore drawn from this recovery plan. In addition, advocacy with Ministry of Finance and Development Planning ensured that the government of Liberia also provided funding for some of the most critical elements of the plan, such as hiring of health workers. By the end of the process, the country had a comprehensive strategic approach to guide the recovery process. With some of its elements having secured funding, the country was surely on the path towards building a resilient system able to absorb future health shocks.

Lessons Learned

The key lessons could be summarized across four areas

The high value placed on government stewardship of the recovery planning process. This does not mean that the MoH had all the answers, but that it has a clear vision of where it wants the system to be, and it relentlessly pursued all actions undertaken towards this. Right from the President to MoH technical officials, there was one clear vision – a rebuilding of the health system in a manner that will ensure such a tragedy never happens again.

Transparency and participation were very critical in building the confidence and alignment of partners around the recovery strategy. Targeted working with partners ensured that there was clear division of labour and partners were able to focus on areas where they have a comparative advantage. While many partners want to be involved in every stage of the decision making process, this was leading to confusion and stasis. The decision of the MoH to only engage at the technical level on a ‘need to’ basis greatly facilitated the process. Working with and across other health related sectors was very critical, particularly in ensuring that phase 3 succeeds.

Way forward

Liberia’s investment plan for building a resilient health system harnesses key lessons learned from post-conflict health sector reforms and the Ebola outbreak to select priorities for building back the health system better [19]. There is still a lot of uncertainties and lack of consensus on the best way to build a resilient health system [7]. Some stakeholders have argued that rebuilding efforts should focus on the outputs that are intended such as improved maternal and child health services. It is nevertheless understood that a health system with any of the six building blocks dysfunctional(service delivery, health workforce, information, medical products, vaccines and technologies; financing; leadership and governance) may not be able to deliver high quality and efficient health services to the people [20,21] While the selective approach may be cheaper and easier, it may not deliver on the medium term goal of providing quality health services to the population in an efficient and equitable manner. Therefore, investments that adopt a more holistic and integrated approach in addressing the root causes of the weaknesses in the health system should be the preferred option rather than a selective remedy which has the propensity of undermining the country’s effort to build a resilient health system [20]. The current approach focuses on both investing in inputs as well as improving how the health system actually operates. If Liberia must make progress post-Ebola towards achieving Universal Health coverage, the health SDG and health security, building a resilient health system is key [22,23]. The selected investment priorities are quite significant as they reflect the foundations that must be put in place in terms of the capacities and resources needed for sustainable improvements in the health of the people. Skilled and motivated health workers are urgently needed in the right numbers to provide quality services in health facilities adequately equipped with facilities appropriate for the level of care as well as essential medicines and supplies [24]. The health workforce at the county, district and health facility levels must have the capacity for early detection, investigation, confirmation and initial response to disease outbreaks and other public health threats. Laboratory capacity must be strengthened to support the surveillance system in promptly confirm the causes of disease outbreaks. This will reduce the risk posed by epidemicprone diseases and enhance the country’s core capacity for implementing the International Health Regulations.

Finding the resources to implement the plan is vital. The total budget may be high but tough decisions have to be made in allocating the resources needed despite the multiple and competing developmental priorities facing the country. Failure to do so will leave the health system fragile and highly susceptible to future shocks. Unfortunately, Liberia whose economy experienced significant setback as a consequence of the Ebola outbreak, and further compounded by increased global recession like many other poor sub-Saharan countries, does not have sufficient domestic resources to invest in the health sector, hence will require major external support for a fairly long time. Worse still, is that the current fiscal space is insufficient for the inflow of substantial financial resources on the implementation of the investment plan. Government needs to create sufficient fiscal space to accommodate the additional budgetary resources for health without prejudice to her financial sustainability for example, through re-prioritization, tax regimes or external grants [25].

Equally critical is the establishment of cost-effective local health financing mechanisms that will alleviate the high out-of-pocket expenditure by the population [26]. Existing Health sector Pool fund mechanism needs to be restructured and managed by government in the form of a health equity fund based on a social insurance approach. This will provide financial risk protection, prevent disparities in the quality of care and ensure that the population can access needed health services without further impoverishment already exacerbated by the Ebola crisis.

The governance and accountability structures at national and county levels are currently insufficient for the inflow of substantial financial resources for the implementation of the investment plan. The health sector leadership at all levels should be empowered to strengthen leadership, governance mechanisms and accountability frameworks in support of the implementation of the Plan.

Increased political will and commitment to leveraging investments and translating them into critical services for the people is the cornerstone to success. Through policy reforms, and strong intersectoral collaboration, other sectors and agencies such as the Ministries of finance and development, Education, Gender and social welfare, and the civil service Agency, could buy-in and additional resources leveraged in support of the implementation of the Plan. Colombia in its health reform agenda (2012–2021), attained 98% population access to health services by adopting a right based policy approach and conceptual model based on social determinants of health that involved non-health sectors [27].

While a plethora of external partners and donors are already operating in the country, coordinating them effectively and monitoring the effectiveness of aid will continue to be a major challenge that government has to surmount. Rwanda was confronted with similar challenges after twenty years of conflict but the implementation of innovations to address them has now placed the country on the pathway to improving its health system [28]. In contrast, Haiti’s health system has remained dysfunctional six years after the earthquake due to patchy health system rebuilding efforts by external aid and the government’s weaknesses in effectively coordinating and monitoring of external aid [29]. Global actors and external donors need to cooperate with the government in adopting a comprehensive and integrated approach and mobilizing substantial resources to support the implementation of the investment plan. The government may consider joining the IHP+ partnership and signing a compact as a means of the alignment of partner funding with the investment plan priorities and promote mutual accountability [30]. As a first step, unspent Ebola response donor funds should be reprogrammed to support the implementation of the investment plan.

Finally, the private sector and civil society play a critical role in health service delivery in Liberia and promoting partnerships with them can contribute to improving access to services, and healthcare financing and accelerate progress towards Universal Health coverage [23,31]. A clear and robust publicprivate partnership policy and framework should guide these partnerships

Conclusion

This paper described the experience of Liberia in the development of an investment plan for building a resilient health system following the 2014-15 Ebola crisis, the approaches, process and realignments that were undertaken, lessons learned, and the way forward. The Liberia’s investment plan is ambitious and will require enormous financial resources that the Government of Liberia alone does not currently have and, therefore, would need long term external support. The Ebola outbreak revealed the weaknesses of the health system in Liberia following a period of under-investment in the sector and what is crucially needed now is to build back better. In the future, further insights may be required to compare various frameworks for post -crisis health system recovery and resilience building in different settings and the impact on emergency preparedness, system performance and health outcomes.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. EM, MG, HK, PT and AG work for the World Health Organization. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policy of the World Health Organization.

Authors' Contributions

YZ, EM conceived the paper, and contributed to the design and preparation of the first draft. YZ, EM, CW, BH, MW, HK, PT, BD and AG contributed to literature search, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Luke Bawo, Miatta Gbarnya, Vera Mussah, Loiuse Marpleh, Tornorlah Varpilah, Angela Benson, Moses Galakpai, Francis Kateh, Tolbert Nyenswah, Matthew Flomo, Joseph Jimmy, Sarkoh Sayde, Ernest Gonyon, Emmanuel Dolo, Eric Johnson, Jennifer Ljungqvist, Tana Wuliji, Ramesh Krishnamurthy, Andre Griekspoor, George Conway, Ngashi Ngongo, Jerome Pfaffmann.

18326

References

- Newbrander W, Waldman R, Shepherdâ€ÂÂÂÃÂBanigan M (2011) Rebuilding and strengthening health systems and providing basic health services in fragile states. Disasters35:639-60.

- Witter S (2012) Health financing in fragile and post-conflict states: What do we know and what are the gaps? Social Science & Medicine 75: 2370-7.

- KienyMP, Evans DB, Schmets G, KadandaleS (2014) Health-system resilience: reflections on the Ebola crisis in western Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization92: 850-850.

- Global health expenditure database [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. (Accessed June 12, 2016, at https://apps.who.int/nha/database.)

- Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, Pang T, Bhutta Z, Hyder AA, et al. (2004) Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium development goals. The Lancet364:900-906.

- Frieden TR, Damon I, Bell BP, Kenyon T, Nichol S, et al. (2014) Ebola 2014—new challenges, new global response and responsibility. New England Journal of Medicine371:1177-80.

- Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT (2015) What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet 385:1910–2

- Nyenswah TG, Kateh F, Bawo L, Massaquoi M, et al. (2016) Ebola and Its Control in Liberia, 2014–2015. Emerging infectious diseases 22:169.

- Kruk ME, Freedman LP, Anglin GA, Waldman RJ (2010) Rebuilding health systems to improve health and promote state building in post-conflict countries: A theoretical framework and research agenda. Social Science & Medicine 70: 89-97.

- Republic of Liberia(2007) National Health Policy: National Health Plan 2007-2011. Ministry of health & social welfareMonrovia, Liberia.

- Republic of Liberia (2011) National Health Policy: National Health Plan 2011-2021. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare Monrovia, Liberia

- Republic of Liberia (2015) Investment Plan for Building a Resilient Health System in Liberia, 2015-2021. Ministry of Health, Monrovia.

- Varpilah ST, Safer M, Frenkel E, Baba D, Massaquoi M (2011) Rebuilding human resources for health: a case study from Liberia. Human resources for health 9:11.

- World Health Organization (2015) World Health Statistics 2015. Geneva: WHO.

- UNDP (2013)The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World.Human Development Report.

- World Health Organization (2014) High level meeting on building resilient systems for health in Ebola-affected countries. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Boozary AS, Farmer PE, Jha AK (2014) The Ebola Outbreak, Fragile Health Systems, and Quality as a Cure. JAMA312: 1859-1860.

- World Health Organization (2007) Everybody's business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO's framework for action. Geneva.

- Marchal B, Cavalli A, Kegels G (2009) Global health actors claim to support health system strengthening—Is this reality or rhetoric? PLoS Med 6: e1000059.

- Chee G, Pielemeier N, Lion A, Connor C (2013) Why differentiating between health system support and health system strengthening is needed. Int J Health Plann Manage 28: 85–94.

- Kutzina J, Sparkesa SP (2016) Health systems strengthening, universal health coverage, health security and resilience. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 94:2-2.

- Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Tornorlah VS, Macauley R (2011) Population preferences for health care in liberia: insights for rebuilding a health system. Health services research 46:2057-78.

- Durairaj, V,Evans DB (2010) Fiscal space for health in resource poor countries. World health report..

- World Health Organization (2014) Country Cooperation Strategy. Columbia.

- Logie DE, Rowson M, &Ndagije F (2008) Innovations in Rwanda's health system: looking to the future. The Lancet372: 256-261.

- Ivers LC (2011) Strengthening the Health System While Investing in Haiti. AmericanJournal of Public Health 101(6): 970–971.

- International Health Partnership (2016) A global ‘Compact’ for achieving the millennium development goals.

- O'Connell T, Rasanathan K, Chopra M (2014)What does universal health coverage mean? The Lancet 383: 277-279.