Case Report - (2023) Volume 17, Issue 8

Stress Related Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis: A Case Report

Boubdir Safaa*,

EL Kholti Wafa,

Rhalimi Loubna and

Kissa Jamila

Department of Periodontics, University of Hassan II of Casablanca, Casablanca, Morocco

*Correspondence:

Boubdir Safaa, Department of Periodontics, University of Hassan II of Casablanca, Casablanca,

Morocco,

Email:

Received: 21-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. IPHSJ-23-14053;

Editor assigned: 26-Jun-2023, Pre QC No. IPHSJ-23-14053 (PQ);

Reviewed: 10-Jul-2023, QC No. IPHSJ-23-14053;

Revised: 22-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. IPHSJ-23-14053 (R);

Published:

19-Sep-2023, DOI: 10.36648/1791-809X. 17.9.1056

Abstract

The basic form of necrotizing periodontal disease is

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis (NUG). It has a rapid and

aggressive start and a complex aetiology that includes

stress, nutritional deficits and immune system dysfunctions.

NUG is distinguished clinically by inflammatory interdental

papillae, gingival necrosis, gingival discomfort, bleeding and

halitosis. The therapy of NUG comprised a first phase that

should be administered immediately in order to halt disease

progression and regulate the patient's discomfort and pain.

The second phase of the preexisting condition's treatment,

followed by surgical correction of the disease's sequelae.

Following the completion of active therapy, a periodontal

maintenance programme was created. The purpose of this

case report is to present the method to diagnosis and

treatment of NUG in a male patient with no systemic

disease, as well as the likely mechanism of pathogenesis of

predisposing factors implicated.

Keywords

Diagnosis; Necrotizing Periodontal Diseases

(NPD); Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis (NUG); Treatment;

Stress

Introduction

Necrotizing periodontitis is one of the most severe

inflammatory reactions of periodontal tissues caused by dental

plaque. These disorders have a quick, acute onset, as well as a

multiple and complex aetiology. Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

(NUG) is a classic example of a necrotizing periodontal disease. It

is a common kind of periodontal disease caused by bacterial

infection in people who have certain underlying risk factors

(poor dental hygiene, smoking, stress, poor nutrition, reduced

immunological function, etc).

Clinically, NUG is distinguished by high dental plaque

accumulation, quick onset of gingival discomfort, interdental

gingival necrosis, bleeding and tissue necrosis. It is also linked to

fever and lymphadenopathy. During World War II, NUG was

observed among military soldiers due to a combination of risk

factors (poor oral hygiene, significant psychological stress and

inadequate diet). NUG is seen in people with immunecompromised conditions after the conflict. According to current

data, the prevalence of NUG ranges from 6.7% in Chilean

students aged 12 to 21 years to 0.11% in the British armed

forces [1].

The periodontal therapy of NUG is aimed at remission of the

acute process's signs and symptoms, including the removal of

the local causative factors and comfort of the painful condition.

The purpose of this case study is to describe a localised form of

NUG's therapy strategy and successful outcomes.

Case Presentation

In June 2022, a 22-year-old male patient presented to the

department of periodontology, faculty of dentistry, university of

Hassan II of Casablanca, Morocco, with painful gingival

inflammation that had been present for three days. The patient

complained of sudden intense discomfort and gingival bleeding.

We observed a slender, feverish, fatigued male during the

clinical examination, but no adenopathy on the cervical ganglia

area. He was a nonsmoker with poor plaque management and

no parafunction. There was no other significant medical history

or recognised allergies [2].

Clinical findings and diagnostic assessment

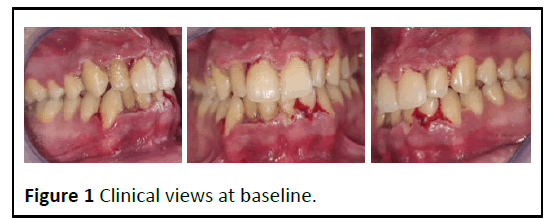

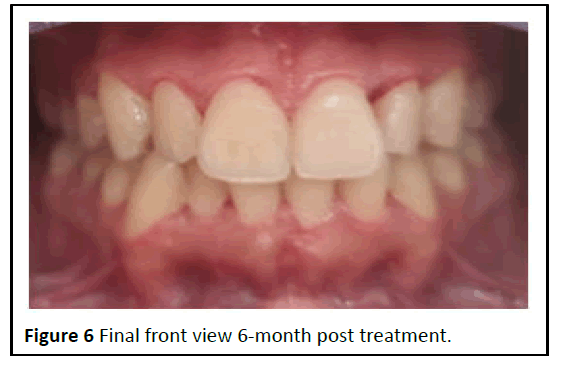

Clinical examination indicated a pseudo membrane formation

along the gingival edges, as well as headless ulcerated papillae,

particularly on the upper anterior teeth and lower central

incisors (Figure 1). In rare cases, the papilla did not completely

fill the interproximal area. On the teeth surfaces, there was a

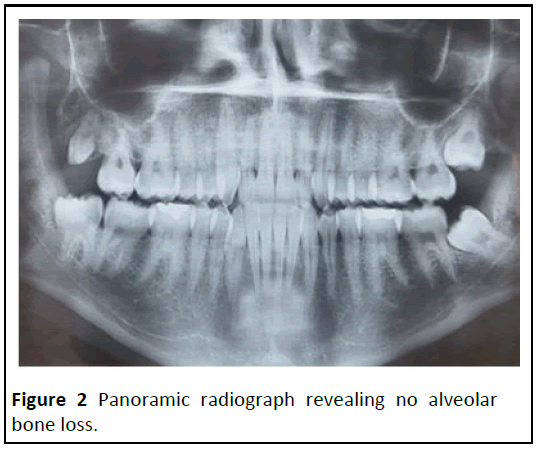

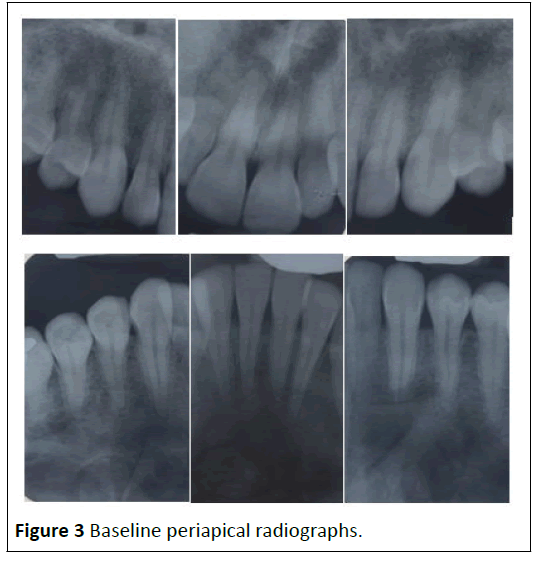

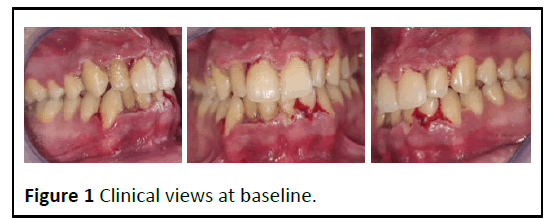

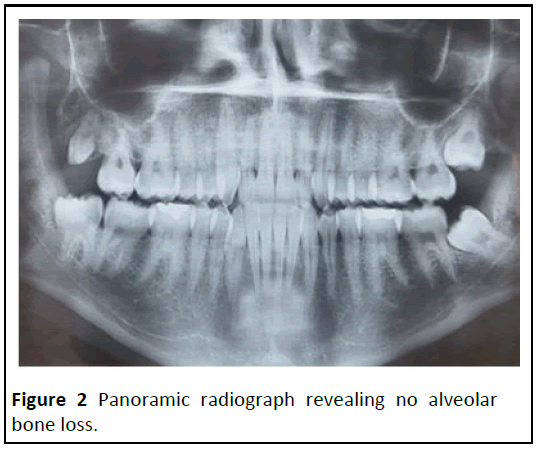

generalised and extensive deposit of dental plaque. X-rays

revealed periodontal ligament expansion in the lower central

incisors but no alveolar bone loss (Figures 2 and 3). During the

physical examination, no systemic condition that could

predispose the patient to NUG was discovered. However, the

patient indicated that he had been under considerable stress

and psychological pressure at school as a result of a period of

academic probation. Based on the clinical data obtained at the

examination, NUG was diagnosed [3].

Figure 1: Clinical views at baseline.

Figure 2: Panoramic radiograph revealing no alveolar

bone loss.

Figure 3: Baseline periapical radiographs.

Therapeutic approach

The primary clinical treatment goal was to shorten the acute

period of NUG. Using sterile swabs and appropriate ultrasonic

supragingival debridement, we administered diluted hydrogen

peroxide to the necrotic pseudomembranous lesions. The

patient was given an oral antibiotic (250 mg metronidazole

every 8 hours for 7 days) as well as an oral mouth rinse (0.12%

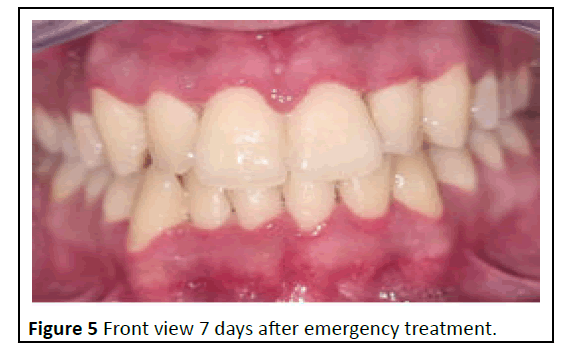

chlorhexidine twice day for 10 days). The gingiva condition was

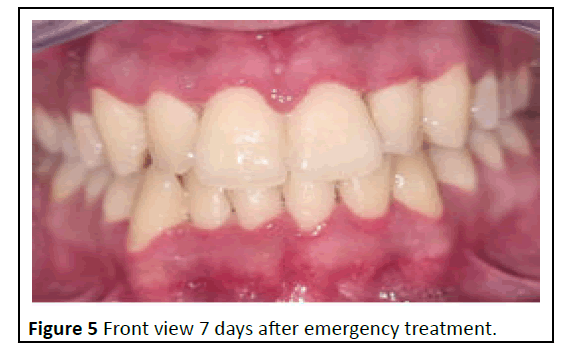

assessed two days and seven days after therapy. The clinical

examination revealed that the patient's condition was improving, with less erythema and swelling. A subgingival

debridement was performed two days following the emergency

therapy [4].

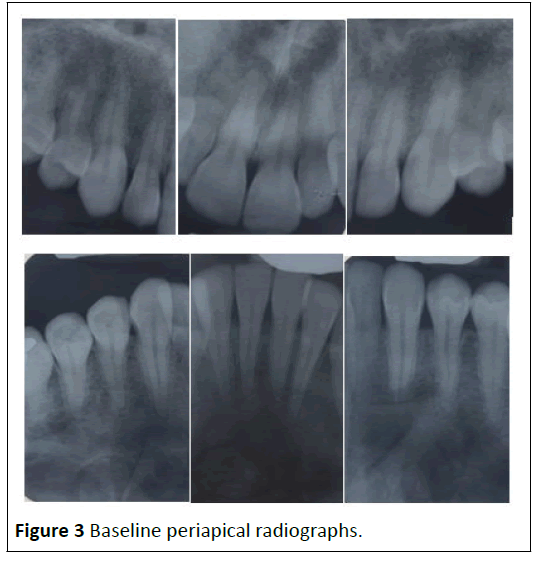

A reinforcement of the oral hygiene instructions was realised

in order to change the patient's oral hygiene behaviour with

regular and effective oral hygiene habits maintenance. Within

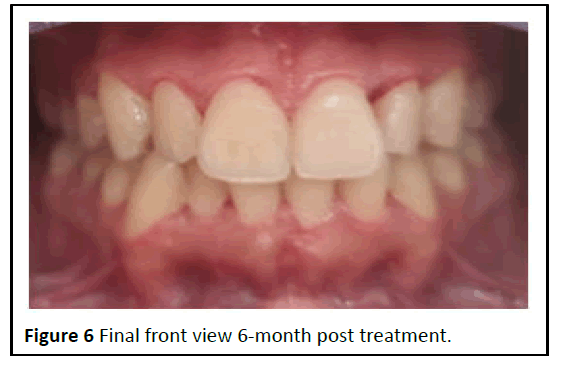

two weeks, the inflammatory clinical state was corrected and

periodontal health was noted. The patient was seen once a

month on a regular basis. There was no tissue squealing, thus

the evolution was positive (Figures 4-6) [5].

Figure 4: Clinical views 2 days after emergency treatment.

Figure 5: Front view 7 days after emergency treatment.

Figure 6: Final front view 6-month post treatment.

Results and Discussion

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis is limited to the gingival tissue

and does not impact other periodontal tissues. The World

Health Organisation (WHO) designated NUG, along with

Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis (NUP) and linear gingival

erythema, as periodontal disease-related diseases in HIVpositive

patients in 1993. Later, according to the American

academy of periodontology's 1999 categorization scheme, NUG

was classed as necrotizing periodontal disease (NUP).

Necrotizing Gingivitis (NG), Necrotizing Periodontitis (NP) and Necrotizing Stomatitis (NS) are severe inflammatory periodontal

diseases caused by bacterial infection in patients who have

certain risk factors (poor dental hygiene, smoking, stress, poor

diet, reduced immunological function and so on [6].

In the present case report, systemic clinical symptoms indicate

the less severity of the case. The typically histopathological

aspect of NUG is described on four different layers from the

most superficial to the deepest layers of the lesion:

• The bacterial area with a superficial fibrous mesh composed of

degenerated epithelial cells, leukocytes, cellular rests and a

wide variety of bacterial cells, including rods, fusiforms and

spirochetes.

• The neutrophil rich zone composed of a high number of

leukocytes, especially neutrophils and numerous spirochetes

of different sizes and other bacterial morphotypes located

between the host cells.

• The necrotic zone, containing disintegrated cells, together with

medium and large size spirochetes and fusiform bacteria.

• The spirochetal infiltration zone, where the tissue components

are adequately preserved but are infiltrated with large and

medium size spirochetes. Other bacterial morphotypes are not

found [7].

The diagnosis of NUG can be confused with some viral

infections (acute herpetic gingivostomatitis and infectious

mononucleosis…), bacterial infections (gonococcal or

streptococcal gingivitis) and also some mucocutaneous

conditions (desquamative gingivitis, multiform erythema,

pemphigus vulgaris). The risk factors play a significant role in

NUG by suppressing the host immune response and enhancing

bacterial pathogenicity. Psychological stress, low sleep and poor

diet are among these variables. In this case, two NUG risk factors

were suspected: Poor diet and psychological stress caused by

tests. The proposed mechanisms to explain the relationship

between psychological stress and NUG are based on reductions

in gingival microcirculation and salivary flow, as well as increases

in adrenocortical secretions, which are associated with changes

in the function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and

lymphocytes. NUG therapy modalities are organised in three

steps: First, treat the acute phase; second, treat the previous

condition; and last, treat the illness sequelae [8]. Then comes

the supportive or maintenance phase. The goal of acute phase

treatment is to stop the disease process and tissue

deterioration, as well as to regulate the patient's general sense

of discomfort and pain, which may interfere with nutrition and

oral hygiene practises. These goals can be met through careful

superficial ultrasonic debridement and chemical deterrence of

necrotic lesions with oxygen-releasing chemicals, referred to as

"local oxygen therapy." Metronidazole (250 mg, every 8 hours) is

the primary choice of medicine for systemic antimicrobials due

to its active action against stringent anaerobes. Other systemic

medications with acceptable results in the literature include

penicillin, tetracyclines, clindamycin, amoxicillin or amoxicillin

with clavulanate. Locally delivered antimicrobials are not

recommended for the huge number of bacteria present in

tissues, where the local medication will not acquire acceptable

concentrations. Antifungal drugs are especially useful in

immunocompromised patients receiving antibiotics [9]. Once the acute phase is under control, treatment of the previous

chronic illness, such as chronic gingivitis, should begin, which

may include professional prophylaxis and/or scaling and root

planing. Instructions on oral hygiene and motivation should be

strengthened. Overhanging restorations and interdental open

areas, for example, should be addressed as predisposing local

variables. Systemic risk factors such as smoking, insufficient

sleep and stress reduction should be addressed and controlled.

Treatment success is dependent not only on biofilm control

approaches, but also on patient behaviour change and

adherence to treatment regimens. In the current clinical

example, patient compliance was a beneficial aspect in the

clinical situation's favourable evolution. He has good plaque

control, follows control appointments and is still in the

maintenance phase [10].

Conclusion

NUG is a form of periodontal necrotizing disease. Different

clinical and systemic symptom and risk factors are behind the

diagnostic assessment. Treatment should be organized on

successive stages and the acute phase treatment should be

provided immediately to prevent sequelae and craters in soft

tissues that could lead to new relapses. Finally, a good

compliance with the oral hygiene practices and maintenance are

the guarantee of successful outcomes.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- Ardila CM, Guzman IC (2016) Association of P orphyromonas gingivalis with high levels of stress-induced hormone cortisol in chronic periodontitis patients. J Investig Clin Dent 7: 361-367.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dufty J, Gkranias N, Petrie A, McCormick R, Elmer T et al. (2017) Prevalence and treatment of Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis (NUG) in the British armed forces: A case-control study. Clin Oral Investig 21: 1935-1944.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Folayan MO (2004) The epidemiology, etiology and pathophysiology of acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis associated with malnutrition. J Contemp Dent Pract 5: 28-41.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Herrera D, Alonso B, de Arriba L, Santa Cruz I, Serrano C et al. (2014) Acute periodontal lesions. Periodontol 65: 149-177.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmstrup P, Westergaard J (2003) Necrotizing periodontal disease. Clinical Periodontology and Implant dentistry, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 243-259.

[Google Scholar]

- Holmstrup P, Plemons J, Meyle J (2018) Non-plaque-induced gingival diseases. J Clin Periodontol 45: 28-43.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu J, Kent P, Lennon JM, Logan LK (2015) Acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis in an immunocompromised young adult. BMJ Case Rep 2015: bcr2015211092.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lopez R, Fernandez O, Jara G, Aelum VB (2002) Epidemiology of necrotizing ulcerative gingival lesions in adolescents. J Periodontal Res 37: 439-444.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malek R, Gharibi A, Khlil N (2017) Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Contemp Clin Dent 8: 496.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martos J, Ahn Pinto KV, Feijo Miguelis TM, Cavalcanti MC, Cesar Neto JB (2019) Clinical treatment of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis: A case report with 10-year follow-up. Gen Dent 67: 62-65.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Safaa B, Kholti W, Loubna R, Jamila K (2023) Stress Related Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis: A Case Report. J Health Sci. Vol. 17 No. 09

1056.