Keywords

Stroke, patients, satisfaction, nursing care.

Introduction

Hospitalization can be a traumatic event for many people especially when afflicted by a sudden stroke or heart attack. For older citizens adjustments to new environment can add a further anxiety. Research on the attitudes and experiences of stroke patients during hospitalization has its difficulties yet investigations need to be done in order for services to be improved and to provide nurses and other caring stuff an empathetic insight into the patients’ world [1,2].

This paper studies attitudes within a week of returning home. Previous research has shown that face-to-face interviews had advantages over other methods of data collection e.g. self completed questionnaires, as they afforded flexibility and provided immediate opportunity for clarification of meaning [3]. Furthermore, interviews provide an opportunity to observe and assess the validity of the response [4,5]. A semi-structured interview makes it easier for a patient to express views and opinions verbally, rather than in writing [6,7]. This view is also supported by Kenworthy et al., [8] who argue that the interview format offers greater scope than questionnaires, which are rigid and brief, thus often oversimplifying complex problems.

Aims

This study explored the experiences of elder stroke patients who had recently been treated in hospital. In addition, it was intended to describe their feelings with the nursing services offered.

The objectives of the investigation were:

i) To provide an in-depth description of how these patients perceived the care they were offered.

ii) To identify aspects of satisfaction and dissatisfaction of the care received.

Material and Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 14 rehabilitated stroke patients who were approached on a single day whilst in hospital. Written consent to participate in the study was obtained from all. Respondents were initially approached during their hospital stay and interviewed later at their own homes within two weeks of discharge. Seven from a Rehabilitation ward, and four from an Acute Stroke Unit. In total, 11 of the initial sample of 14 were interviewed because two had a further vascular episode which affected their speech and perception and made communication impossible, and the third died immediately after discharge. Seven (64%) were women, the mean age was 72 years with a median age of 73 (range: 60-88). They stayed in hospital for 476 days in total, with a mean length of stay of 43 days.

Criteria for inclusion

Respondents were to be over 60 years of age, should understand and speak English comprehensively and should not suffer from severe mental problems which might obstruct communication; severe pain or any other serious post treatment medical implication, where interview participation might have a negative impact on their recovery.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted prior to the study by the hospital’s ethics committee and a consent form was also approved. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured while permission was sought for the use of a tape recorder

Data collection

An exploratory descriptive research design was chosen, because of the interpretive framework underlying the whole process. The aim was to attain detailed insight into the nature and the social context of the personal meanings of hospitalisation experience for each individual under investigation. Data were collected by means of face-to-face, open-ended, semi-structured interviews in order to encourage spontaneous responses. For this study the research design was a modification of that of Brink and Wood [9].

Interview prompts aimed to cover some of the six broad areas of patient satisfaction as defined in the literature: patient treatment-care; meal arrangements; pattern of patient's day; doctor/nurse/patient relationship; personal activity/responsibility and the ward environment [10,11]. The purpose of these questions was two-fold. Firstly, to prompt and keep the conversation in the context of the subject under exploration, and secondly to start a dialogue which should soon develop into a monologue where the interviewee would be encouraged to narrate his personal experience, feelings and perceptions of the care he had been given.

Interviews lasted between 30 and 40 minutes, were tape recorded and field notes were taken in order to enrich the data by recording non-verbal signs or the respondents’ reactions to specific questions (gestures, genuine or ironic smiles, sighs etc). Participants were informed that they could stop at any stage without having to justify their decision.

Data analysis

Data were analysed by means of content analysis of the interview transcripts as devised by Krippendorff who outlined as follows [12]:

Definition of recording unit: the first step was to divide each transcript into phrasal, word statements or sentences.

Definition of sub-categories: all recording units were sub categorized in a mutually exclusive way so that all relevant data were coded in some category.

Test coding on sample of text: this was like a pilot analysis where categories were applied to a small sample of the text in order to reveal any ambiguities regarding the classification scheme.

Assessment of the accuracy or reliability: Here reliability refers to the degree of correctness by which the whole text has been coded.

Assessment of the achieved accuracy or reliability: data were handled by hand and one researcher was used to prevent the coding discrepancies and reviewed by two colleagues to ensure reliability (K statistic 90% reliability).

Findings and discussion

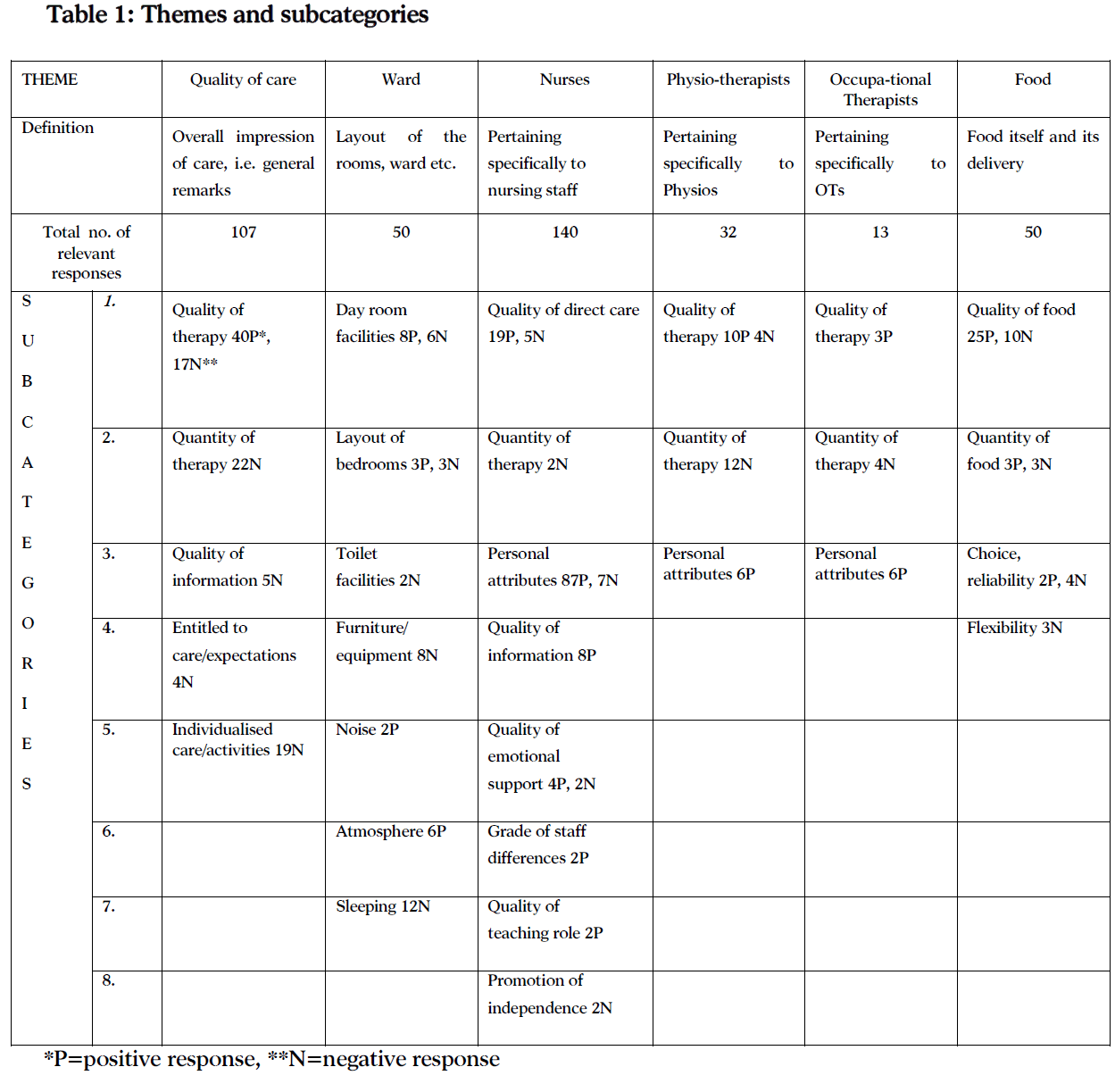

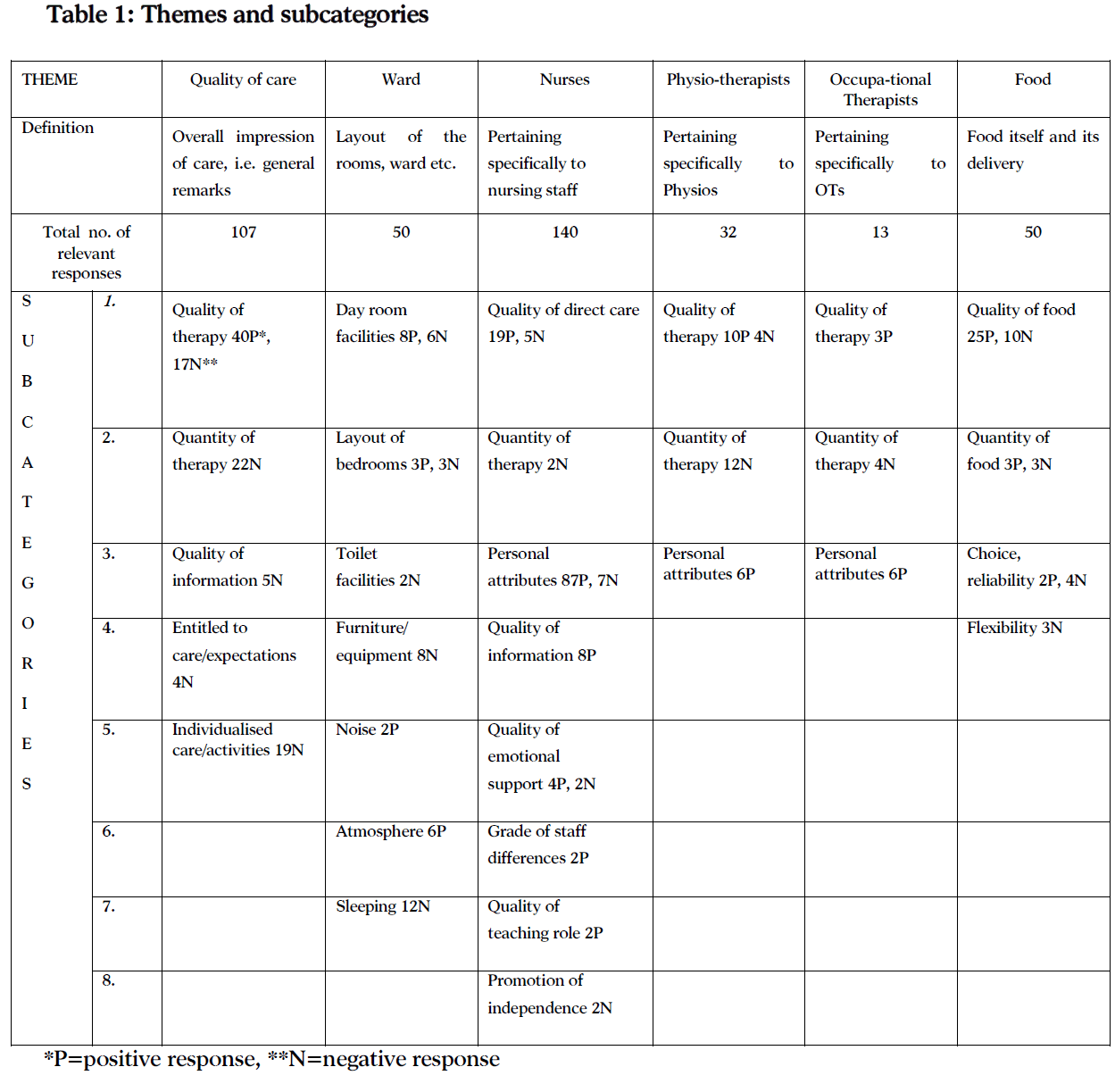

Transcripts were divided into spontaneous statements (2761 in total) and were initially divided into two broad groups, those that were "irrelevant" (2280) such as greetings, introductory phrases or rhetoric eg “It is nice to be back home”. With regards to the research topic, there were 392 relevant statements. These were clustered together under common headings "sub-categories" which reflected the more in-depth meaning of the statements. Consequently, relevant categories were amalgamated into broad areas "themes" which included sub-categories as shown at the top of table 1. Finally, within each sub-category, statements were then divided into those with a positive inference and those with a negative one. All findings are summarized in table 1.

QUALITY OF CARE

There were 107 references of which 67 were negative, which addressed various degrees of dissatisfaction with different aspects of the quality of care that patients received. Patients indicated that the quality of therapy that the hospital offers was not in line with their expectations or standards. Many respondents provided comments which describe very vividly the way they felt about the therapy they received in general. One of the respondents said: "I was petrified, to be honest", while another complained of being, "Frightened in there". There were also a lot of complaints about the Accident and Emergency Department which people disliked: "It was uncomfortable" or "The waiting was horrible". The rest of the references were concerned with the patients' worries and feelings of despair of being in hospital.

An interdisciplinary approach should ensure the patient's psychological well-being as this is inextricably bound up in the quality of care. The patient's morale is of crucial importance in the process of recovery [13]. Patients should be in the right frame of mind and should not be making statements such as: "I was worried about what was going to happen to me, or "I felt like I wanted to lie down and die". These statements reflected an unhealthy mental attitude towards being able or motivated to take an active part in participating in the planning of their future care.

Essentially, people complained that they did not have sufficient treatment. Staff did "Nothing really" or "They did nothing for three weeks", or "They just used to measure my blood pressure". The respondents wanted more information about their proposed hospital stay, the nature of their illness or the way their therapy worked. Typical remarks were "The worst part of being there (hospital) was not knowing what was involved", or "They never tell you how long you are going to be there (hospital)" or might be there. It was not clear at all whose responsibility it was to provide various pieces of information to the patient and who was going to ensure that all the relevant and appropriate information had been given. Information flow to the patient was perceived as disorganised, non-linear and at times contradictory.

Entitlement of care/expectations was epitomized by one respondent’s stoic statement: "They (staff) have enough to think about rather me not liking it in here (hospital)". Although this category had only 4 references, it is of particular importance because consumer’s expectations and feelings of entitlement for any medical experience influence whether, when and how they will seek care [14].

Comments relating to individual care included complaints about boredom and lack activities. One patient for example stated "You just fill in your own time; you are left to your own devices". These accounts become even more significant when one considers the fact that almost all of the respondents spent considerable time on a rehabilitation ward where it is assumed that patients receive maximum input from different professionals following a plan for each patient. Various studies have demonstrated the very limited amount of time that patients spent in active rehabilitation [15,16]. The findings from this study appear to support this account.

THE WARD

Patients felt that the Day Room facilities were very limited "There was just a telly, wasn't there?" and perhaps it would have been more honest to call it the TV Room, instead. Reasons for under-use of the Day Room had also to do with choice over the use of the television programmes, "I am not interested in football and things".

All three wards had a mixture of bay sizes i.e. there were 5-bedded rooms and also one bed side rooms. The respondents felt that smaller rooms were generally better. Respondents disliked being near the window as: "It was drafty and freezing". Perhaps it is widely thought that being next to the window is the best place to be as it provides easy access to light and view, yet fear of catching a cold understandably seemed to be a high priority to them.

Toilets were said to be small with: "Not enough room in there". Some of the patients did not need much help in going to the toilet, but the majority had conditions (poor mobility, reducing standing balance, etc.) that made them very dependent on having easy access to a toilet. A great majority needed the help of one or two persons and therefore the complaint of the toilet size should be should be taken seriously in ward design.

The ward furniture and equipment were heavily criticised. Some thought that the beds were too soft; others stated that they were too hard, but either way the beds were not thought to be comfortable. It is widely acknowledged that elderly patients are more susceptible to developing pressure sores as in-patients, hence the need for special mattresses. The question of whether the patients' personal preference be taken into account thus allowing for a choice of firm or soft mattress is suggested here as an area of further research. It was noteworthy that plastic under-sheets were disliked yet plastic mattress coverings were acceptable.

The ward environment was considered satisfactory by the patients. Statements were somewhat bland: "nice", "lovely" and "fine". Interestingly, also no one complained about noise levels. This finding is not in line with previous research as sleep disturbances in hospital have been a well acknowledged problem [17,18]. In this paper, the sub-category of `sleep` had 12 response statements, all of which were negative. The patients complained of difficulties in falling asleep due to material (uncomfortable beds, heavy blankets) and/or environmental reasons (fellow patients, nurses). "The lady next to me used to scream at night", and "They (nurses) put the lights on and you are bound to be disturbed". Nurses must constantly be sensitive to the patient's need and right to a good night sleep, always ensuring that the ward environment is peaceful during the night. Patients who are agitated should be considered for a single room wherever feasible and staff should try not to disturb the patients during their sleep by using the full capacity of the lights. Dim nightlights should be an alternative.

THE NURSES

The majority of the statements in this study were about the nurses. This is not surprising, due to the fact that nurses are the professionals who are constantly with the patients. It is satisfying to see that the great majority of these statements were positive and that they revealed high levels of satisfaction with various aspects of the nursing input and the nurses themselves.

The respondents commented on treatment as follows: "They treat patients very well". Simple aspects of care, such as giving a bath or helping a patient to walk, were much appreciated. "They gave me a bath and I was feeling a lot better" and "They would take me for a walk which used to make me very happy". Moreover the patients seem to trust nurses because, as one patient said: "They knew what they had to do". However, dissatisfaction was expressed as well. Although there were only 5 negative statements, they were important as they concerned the way patients were physically handled.

Patients complained that: "Some of them were a bit more heavy handed". Concern also arose from the way patients were transferred from bed to chair or helped to get to the toilet: "When they put their hands around you, you can feel that there is no strength there". Safe handling and transferring are of paramount importance for this age group of patients who were certainly aware of the devastating impact that a fall would have had on them [19]. Concern was also expressed for the nurses who had to lift: "I used to worry over her (nurse) lifting me".

Quantity of therapy was summarized in the words of one patient: "They did not spend much time with me, because I was not bad enough". There was asymmetry in the way nursing time was allocated. Apparently patients with less severe problems commented that they were “Left to our own devices".

Nurses were praised for their personal attributes. This was the largest sub-category of responses, almost all of which were positive statements about the nurses' character and behaviour. A variety of descriptions such as "nice", "good", "excellent" etc. were assigned to individuals and to nurses as a group. Particular characteristics that were highly valued were shown by comments such as: "They were quite dedicated to what they did" or, "Most of them took a personal interest in the patient".

Many respondents felt that the nurses were attentive and helpful. Straightforward accounts such as: "They kept coming 3-4 times a day asking if I was all right" and "They used to come and see if you were all right during the night" indicated that there were no significant differences in terms of attendance between day and night shifts, as: "They (nurses) are on the lookout". Being obliging and helpful was another aspect of the nurses' character that was much appreciated: "Anything I wanted they used to give me. If you wanted a cup of tea in the middle of the night they would make you one. They would even make the visitors a cup of tea, which is very nice". Small things like a cup of tea seemed to make a big difference to the way patients perceived the nurses. We should be aware that small kindnesses can have a disproportionably large impact on the way patients perceive our attitudes.

However, there was a minority of negative statements which revealed some dissatisfaction with the nurses' attitudes. These concerned the concept of authority which may have seemed to be patronising and/or condescending. Some nurses were said to be: "On the bossy side" or "Some of them tried to take over you.” Our professionalism should not be confused with power and superiority which are features that can frighten frail or dependent patients. However, many elderly patients are often reluctant to accept any ipso facto control.

QUALITY OF INFORMATION

Patients commented on the way their questions to the nurses were fully answered and relevant explanations given, such as: “Anything I asked, they answered me. Further positive responses indicated that informal introductions were favoured by the patients. For example: "It makes you feel more human when they call you by your first name". Today's nursing practice guidelines dictate that in the first instance the patient should be approached in a formal manner. However patients should have the opportunity soon thereafter to choose the address they feel comfortable with. Consistency should be maintained once a preference has been indicated by the patient. Findings from this study, however, suggest that patients favour a subsequent informal approach.

The quality of emotional support that patients were offered was captured very vividly by one male patient. "I was very emotional in there and she (nurse) helped me to get over this emotional thing". Later on, during the interview, he provided practical accounts for the emotional help he received: "They give you a cuddle as well, you know". However there were 2 instances where patients indicated a lack, rather than poor quality of emotional support. A stroke victim recalled his feelings during the acute phase of the illness as follows: "I could not move my right side, I was feeling completely hopeless, like being at their (nurses) mercy". Hospitalization is a traumatic experience for elderly patients as it is often associated with functional and mental decline [20]. A stroke in particular is a very sudden event that can raise fears of loss of control, permanent loss of physical functions and death. In this light, emotional support should be a crucial element of everyday nursing [21].

The patients were able to detect differences in staff attitudes and in 2 instances student nurses were praised as they were thought to be: "more patient and kind". These remarks suggest that student nurses are generally perceived in a positive way by patients.

The quality of teaching role consisted of only two spontaneous statements. One of the respondents had trouble going to sleep and according to him: "she helped me to go to bed by teaching me how to concentrate". Another respondent valued the way the nurses taught him how to position himself on the chair. Still, the majority of the respondents were on a rehabilitation ward where teaching should be the key function of the nursing input.

The potential level of independence varies from patient to patient, but part of the rehabilitation process is to identify realistic goals that a person is capable of achieving. Individualised attention should help prevent statements like:

"They (nurses) were not personal at all. They just seemed to do things".

THE PHYSIOTHERAPISTS

Several studies showed that early and organised rehabilitation improves function and motor skills, especially in stroke patients. It was also suggested that the rehabilitation process should be continuous, regardless if the patient is in acute care, rehabilitation medical or geriatric ward [22,23].

However, although the nurses are with the patient more than any other health care professional still their input in engaging the patient in rehabilitation activities was found to be poor [24]. Findings presented under this theme support the view that the rehabilitation input was not regarded enough, and patients felt that they would have benefited more if the activities were continuous and were not assumed to be the physiotherapist's entire responsibility.

Moreover, successful rehabilitation of patients following a stroke depends on a positive attitude of mind amongst all the staff. A coordinated approach should be encouraged with each member of the multidisciplinary team respecting and making use of the skills of different professionals for the benefit of the patient [25].

The respondents were happy in general with the quality of physiotherapy they received as the positive statements under this sub-category outnumbered the negative. The patients gave examples of the aspects of the care they regarded of good quality: "I was looking forward to physiotherapy, as I felt was getting somewhere". Good handling and teaching was also very much appreciated, "they helped me the most...they taught me how to walk". Functional outcomes seemed to be a constant worry for some patients who were particularly concerned with their ability to walk: "I was not sure if I could walk again". However, there were also some negative remarks which were mainly associated with the pain that patients experienced during physiotherapy. "It was painful at times, my shoulder was aching after the exercises". Despite the negative comments on pain, the respondents thought that overall, physiotherapy was very useful The quantity of therapy was criticized as "not enough...I don't think I had enough treatment (physiotherapy)". The complete lack of physiotherapy over the weekend and the Christmas holidays were also heavily criticised. Nevertheless, patients felt that increased input from different professionals i.e. the whole team would have speeded up their recovery. "If I had had a full hour of exercises with the physios or the nurses or whoever, I would have been back on my feet sooner".

Patients described the physiotherapists as: "very nice girls, I am very pleased with them". Positive adjectives such as, “good”, “marvellous” and “nice” were used. The patients seemed to value the work of the physios, and intonation on the tapes also indicated that the patients were also very fond of them.

THE OCCUPATIONAL THERAPISTS

The Occupational Therapist's (OTs) role in the multidisciplinary care that patients receive is two-fold. It can take the form of advice and teaching with regard to "activities of daily living" during hospitalisation, or it can be a battery of assessments regarding the patient's abilities in performing these activities at home during a "home visit" or a "weekend leave" [26].

The patients' complaints of not having much therapy from the OTs should be examined under this light. That is, the OT's role on the wards where the study was conducted was limited to home visits. Consequently, the patients' complaints did spot this inadequacy of the therapeutic input.

The quality of the therapeutic input was positively valued in three instances. Patients felt that: "It was very helpful, they made sure that I would be alright at home". The patients felt that they did not receive enough OT therapy. One respondent was quite dismissive as he said that: "I never had much to do with them". Another observed that: "They (OTs) didn't have the time". Patients consistently felt they had not enough OT treatment yet patients were happy with the OTs with regards to their character and attitudes. Adjectives such as “good”, “brilliant”, or “nice” (similar to the ones used to describe the “Physios”). One respondent said: "Oh! They are brilliant girls, all of them".

THE FOOD

There was an element of food enjoyment and food anticipation which was noticeable. A couple of the respondents seemed to value simply the provision of a decent meal which was readily offered: "I was very happy to receive my meals". One should keep in mind that many elderly patients admitted to hospital are already malnourished or on the borderline of malnourishment. Many genuinely appreciated having what they considered high quality meals prepared for them. Nevertheless, they were also negative statements, mostly comments on difficulty with cutting the food or problems with eating it; pies were considered hard, salads difficult to cut and some dishes were considered too dry.

It seemed that the respondents found the amount of food served satisfactory. One commented on “A big supper, which is as big as dinner.” However, a male respondent felt that the food served was not enough but his criticisms were blunted by the fact that the nurses would “Always give me something extra.” During their hospital stay respondents were asked to choose from a list of what they would like to have for their next day's meals. Although the scheme was welcomed by all respondents, there were certain problems, as some of them complained that: "You did not always get what you asked for". This inconsistency between order and actual delivery was justified by the respondents themselves as they seemed to acknowledge that fact that the popularity of some dishes was the main reason for an alternative delivery. As another respondent commented: "If something is good on the menu everybody wants it and they run out, and so they give you something else".

There were also positive remarks which praised the opportunity for choice itself: "It's so nice to have a list to choose from". One should note here that some of the respondents had experienced health care over different stages of the NHS development, and it seems that food choice was particularly welcomed by he patients involved in this study. Earlier findings also showed satisfaction with the food served, yet this sample were not offered a choice [27].

From a dietetic point of view there were some genuine concerns which were expressed in comments such as "It (food) was not specifically geared to people with high blood pressure" or even more detailed: "They give you so much salt and I know that salt is bad for me". And "It seemed to be just general food". Some patients were acutely aware that the hospital food should play a role in their therapy and concerned with more than merely quality and quantity. A possible explanation for this finding is that people nowadays are, in general, more aware of the important role that our diet has on our health. The media are very fond of providing relevant information and for the past few years a certain number of food-messages and clichés have become common knowledge (e.g. "salt raises blood pressure", "cholesterol kills" etc.). Findings from this study suggest that perhaps patients want to be more involved in dietary decisions and the general provision of food altogether. Stroke patients in particular need dietary advice and the earlier this is implemented, the better. In this study, this point was often overlooked. This is a lost opportunity in stroke rehabilitation.

The results from this study suggest that among this sample of elderly patients there were generally high levels of satisfaction with their hospital care. These findings are consistent with previous research [28,29,30]. Interestingly, this finding of contentment with hospital care was contrasted with widely expressed feelings of dissatisfaction with the quality of that care. Although this finding is open to interpretation, looking deeper into the meaning of one particular statement: "It is nice to have a hospital to go to...", it could be argued that satisfaction may have arisen from the appreciation of the NHS with the open access it provides, which is particularly respected by the elderly rather than solely its efficiency in meeting the patient's needs.

In general the patients were very positive towards the hospital staff, and even when they were critical, they provided specific reasons for dissatisfaction (authoritative behaviour, poor information giving, etc). However, reasons for satisfaction were not always clearly defined.

Conclusions

Implications for nursing practice arising from this study suggest that elder patients appreciate friendly, attentive and open behaviour. However, there is less tolerance for authoritative attitudes. Therefore, constant adjustments are required by the staff in order to attain a "smooth" relationship with our clients. Moreover, nursing interventions to assure that the patients have a good night sleep, need to be carefully planned and implemented.

The findings generally show high satisfaction with regards to the quantity and quality of care received from different professionals. Yet, when a global comment on satisfaction was requested, the response would invariably be “satisfactory”. It is noteworthy that this mid-range global response would also apply to those who were critical of the quality and quantity of care of different professionals. We must ask if these global outcomes mask a silent dissatisfaction amongst those who have much to praise and a degree of appreciation in those who express criticisms.

3246

References

- Blixen C, Agich G. Stroke patients’ preferences and values about emergency research. Journal of Medical Ethics.2005;31:608-611.

- Gibbon B. A reassessment of nurses’ attitudes towards stroke patients in general medical wards. Journal of Advanced Nursing.2006;16(11):1336-1342.

- McLaughlin D. Advanced Nursing and Health Care Research. Elsevier, London.2005;45-57.

- Reis H, Judd C. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. Cambridge University Press, New York, 2000.

- Greenwood J. Nursing research: a position paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;9(1):77-82.

- Newell R, Burnard P. Vital notes for nurses: research for evidence-based practice. London: Blackwell Publishing.2006:60-72.

- Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H, Valimaki M. Development and psychometric properties of the Individualized Care Scale. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice.2005;11(1):7-20.

- Kenworthy N, Gilling C, Snowley G. Common foundation studies in nursing. (3rd ed). London: Churchill Livingstone.2002:339-351.

- Brink P, Wood M. Advanced design in nursing research. Newbury Park: Sage. 1989:178-188.

- Artsa M, Kwab V, Dahmena R. High Satisfaction with an Individualised Stroke Care Programme after Hospitalisation of Patients with a TIA or Minor Stroke: A Pilot Study. Cerebrovasc Dis.2008;25(6):566-571.

- Howell E, Graham C, Hoffman A, Lowe D, McKevitt C, Reeves R, Rudd A. Comparison of patients' assessments of the quality of stroke care with audit findings. Qual. Saf. Health Care.2007;16(6):450-455.

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.), London: SAGE Publications.2004;38-46.

- Morris R, Payne O, Lambert A. Patient, carer and staff experience of a hospital-based stroke service. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007; 19(2):105-112.

- Pollock K. Patients' perceptions of entitlement to time in general practice consultations for depression: qualitative study BMJ. 2002;28:325(7366):687.

- de Weerdt W, Selz B, Nuyens G, Staes F, Swinnen D, van de Winckel A, et al., Time use of stroke patients in an intensive rehabilitation unit: a comparison between a Belgian and a Swiss setting. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2001;22(4):181–186.

- Egerton T, Maxwell D, Granat M. Mobility Activity of Stroke Patients During Inpatient Rehabilitation. Hong Kong Physiotherapy Journal.2006;24:8-15.

- Elwood P, Hack M, Pickering J, Hughes J, Gallacher J. Sleep disturbance, stroke, and heart disease events: evidence from the Caerphilly cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health.2006;60(1): 69–73.

- Palombini L, Guilleminault C. Stroke and treatment with nasal CPAP. European Journal of Neurology.2006; 13(2):198-200.

- Lamb S, Ferrucci L, Volapto S, Fried L, Guralnik J. Risk factors for falling in home-dwelling older women with stroke: the Women's Health and Aging Study. Stroke. 2003;34(2):494-501.

- Bradway C, Hirschman K. How to try this: working with families of hospitalized older adults with dementia. American Journal of Nursing.2008;108(10):52-60.

- Kyngas H, Rissanen M. Support as a crucial predictor of good compliance of adolescents with a chronic disease. Journal of Clinical Nursing.2009;10(6):767-774.

- Ward N. Mechanisms underlying recovery of motor function after stroke. Postgraduate Medical Journal.2005;81:510-514.

- O'Dell M, Lin C, Harrison V. Stroke Rehabilitation: Strategies to Enhance Motor Recovery. Annual Review of Medicine. 2009;60:55-68.

- Stanmore E, Ormrod S, Waterman H. New roles in rehabilitation – the implications for nurses and other professionals. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2006;12(6):656-664.

- Corrigan E. Nurses as equals in the multidisciplinary team. Human Fertility.2002;5(1):S97-S40.

- Gilbertson L, Langhorne P. Home-Based Occupational Therapy: Stroke Patients' Satisfaction with Occupational Performance and Service Provision. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000: 63(10):464-468.

- Naithani S, Whelan K, Thomas J, Gulliford M, Morgan M. Hospital inpatients' experiences of access to food: a qualitative interview and observational study. Health Expectations.2008;11(3):294-303.

- Mangset M, Tor E, Førde R, Wyller T. ’We’re just sick people, nothing else’:...factors contributing to elderly stroke patients’ satisfaction with rehabilitation. Clin Rehab. 2008;22(9):825-835.

- Ayana M, Pound P, Lampe F, Ebrahim S. Improving stroke patients' care: a patient held record is not enough. BMC Health Services Research.2001;1(1): doi:10.1186/1472-6963-1-1

- Conroy B, DeJong G, Horn S. Hospital-based stroke rehabilitation in the United States. Top Stroke Rehabil.2009;16(1):34-43.