Key words

Strongyloides stercoralis, peritonitis, colitis

Introduction

Strongyloidiasis is caused by a Strongyloides stercoralis infection. It is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions and also occurs sporadically in temperate areas [1]. Manifestations of this infection can range from asymptomatic eosinophilia in the immunocompetent host to disseminated disease with septic shock in the immunocompromised host, which carry high mortality rate [2].

Human infection occurs when infective (filariform) larvae penetrate intact skin. Once infected, most people have an asymptomatic, chronic infection of the gastrointestinal tract, with less developed waxing and waning of gastrointestinal symptoms.

The unique ability of Strongyloides stercoralis to complete its life cycle within the human host enables the worms to increase their burden dramatically through a cycle of autoinfection, which can end up with disease persistence. A high intestinal worm burden can be manifested as severe malabsorption [3-4] and possibly as hyperinfection syndrome, which usually occurs in immunocompromised hosts but has also been reported in few case series among patients with no known risk factors for immunocompromised state [5-6].

The majority of symptomatically infected patients experience waxing and waning gastrointestinal symptoms that persist for years due to the presence of the adult worms in the small bowel, which induce duodenitis [2].

This report covers a rare case of strongyloides enterocolitis that presented initially with malabsorption, then progressed to colonic perforation and secondary peritonitis in a young patient with no known risk factors for hyperinfection apart from malnutrition.

The Case

A thirty-four-year old, Bangladeshi, male patient, who had been working in Bahrain for eight months as security guard, was presented to emergency department with a history of malaise after fatigue of five days duration. He had history of experiencing chronic abdominal pain with occasional vomiting for more than three years.

On examination, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable, but pale and cachectic. He weighed 39 kg and had bilateral ankle edema. Abdominal examination revealed a distended abdomen with ascitis; all other systemic examinations were within the normal range. Initial laboratory investigations showed severe anemia with hemoglobin of 3.1 gm/dl (microcytic hypochromic picture) and a normal WBC count with no esinophilia. Serum iron was very low (1μmol/l). A liver function test showed hypoalbuminemia, with albumin level of 6 g/ dl. Serum urea, creatinine levels were normal and liver enzymes were not elevated, as were the initial chest radiographs. Other investigations, including folate, B12 and hemoglobin electrophoresis, were all normal, and there was no proteinurea.

One day after hospitalization, he started to develop high-grade fever and worsening of his abdominal pain. Abdominal examination showed tenderness all over, with a maximum at the epigastric region and rebound tenderness. His white cell count increased to 24,000/cu.mm, with 26% bands and 0% esinophil. A septic workup was collected and

the patient was started on antibiotics (Piperacillin-Tazobactam and Metronidazole).

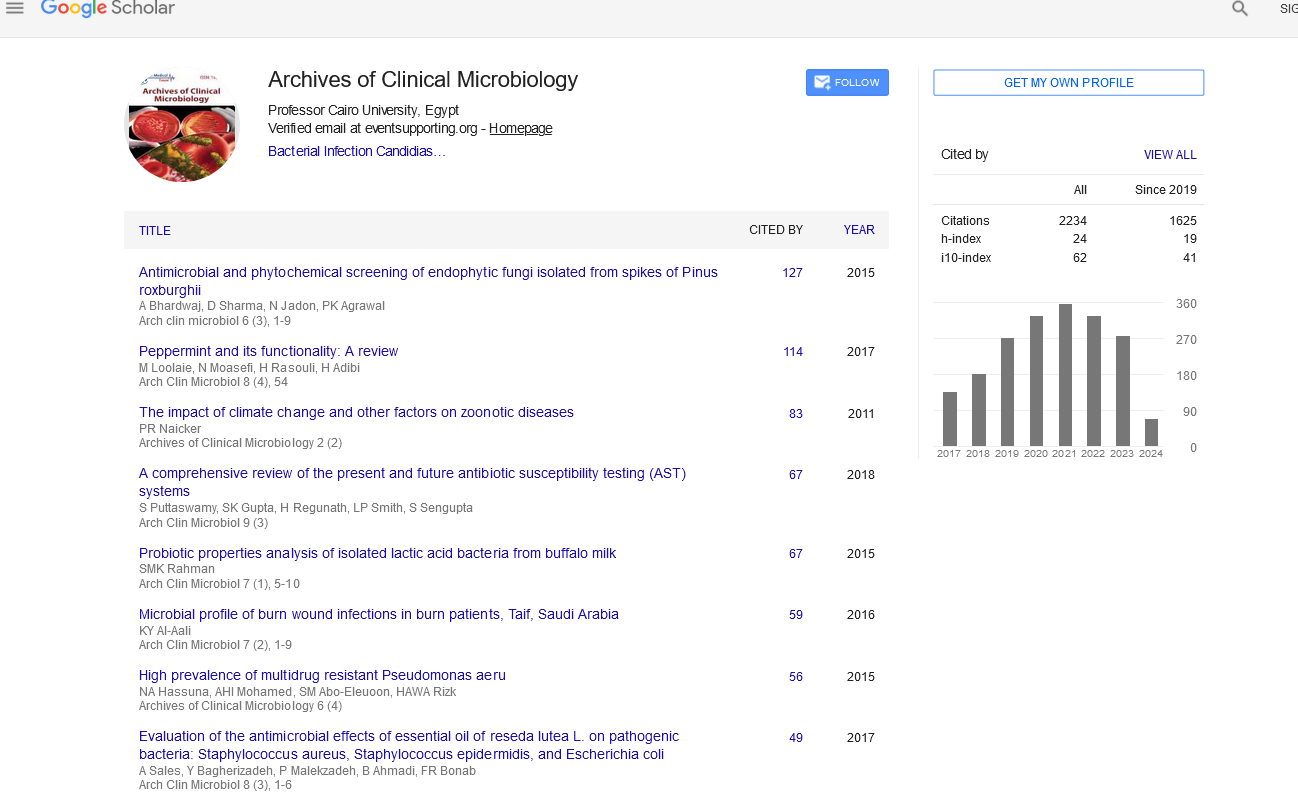

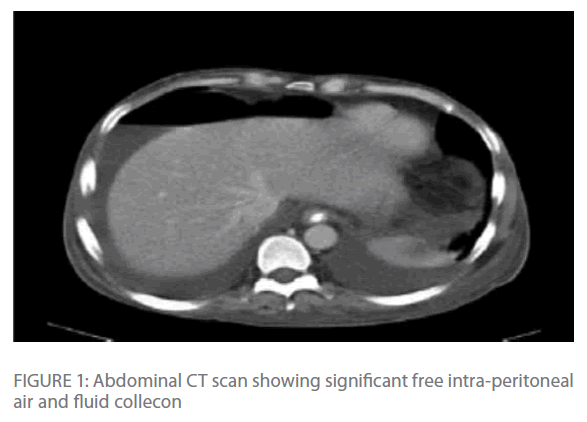

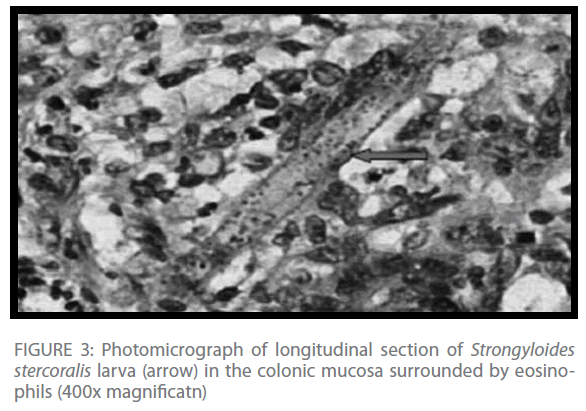

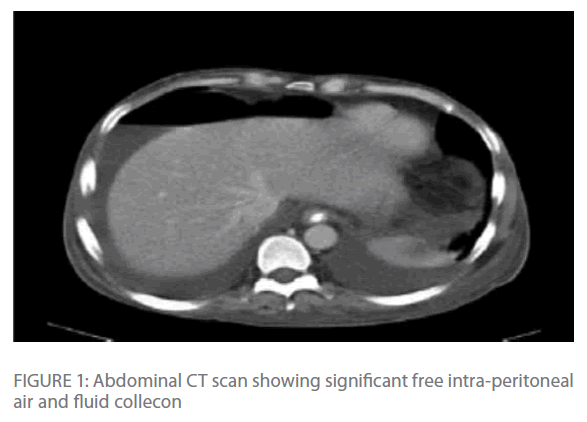

Repeated chest radiographs revealed gas under his diaphragm, which raised the suspicion of a perforated viscous. Subsequently, a CT-scan of his chest and abdomen revealed significant intra-peritoneal air and fluid collection with edema and transmural air in colonic wall (Figure 1 & Figure 2) with normal lung parenchyma.

Figure 1: Abdominal CT scan showing significant free intra-peritoneal air and fluid collecon

Figure 2: Abdominal CT scan showing significant intra-peritoneal air and transmural air and edema of the colonic ll

The patient was given a transfusion of four units of blood and was prepared for surgery. A laparotomy revealed a single sealed perforation of 1 cm diameter at the hepatic flexure of the colon. The area around the colon was severely inflamed, but there was minimal peritoneal contamination. The involved segment of the colon was resected with a proximal colostomy and distal mucous fistula. Wide bore drains were left in the pelvis and the right paracolic gutter.

Postoperatively, the patient was managed in the ICU. The patient improved, and the intra-abdominal drains were removed before his transfer to the general ward after six days of ICU admission.

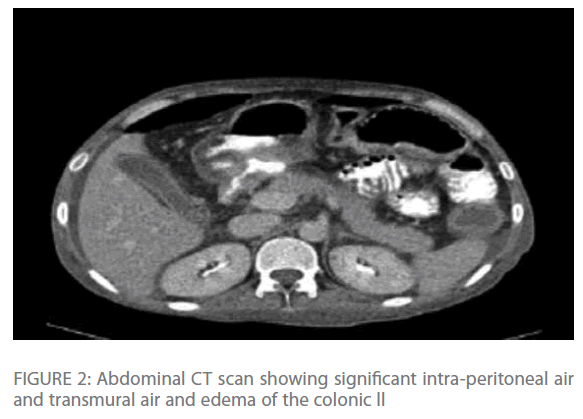

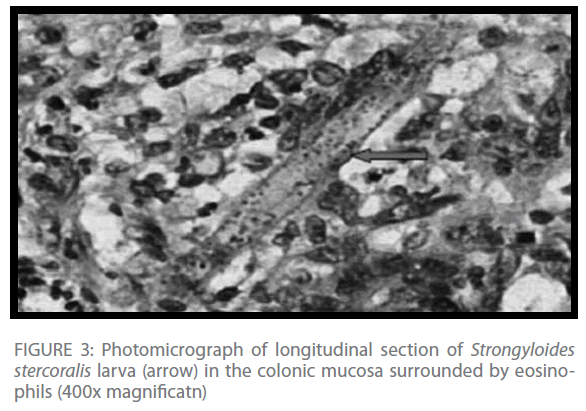

Histopathologic examination of the resected colonic segment revealed a dilated colon with multiple circular deep ulcers. Microscopy showed heavy infiltration of eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils in the mucosa, with heavy infiltration of Strongyloides stercoralis larva (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Photomicrograph of longitudinal section of Strongyloides stercoralis larva (arrow) in the colonic mucosa surrounded by eosinophils (400x magnificatn)

A preoperative stool analysis was sent and it showed Strongyloides stercoralis filariform larva. Three sets of blood cultures were all sterile.

The patient was diagnosed with severe strongyloides colitis, and accordingly he was treated with Albendazole 400 mg twice daily for a total of 14 days. Serology for Strongyloides was positive with high titer.

The patient was discharged after 17 days of hospitalization with a plan for closure of colostomy after three months. Later, after the patient had a closure of colostomy, another stool analysis was completed. This time it was negative for occult blood and Strongyloides.

Discussion

Our patient stated that he had had chronic abdominal pain for few years prior to this acute presentation, which indicates chronic strongyloidiasis.

His presentation with fatigue, lower-limb edema and ascitis was likely due to severe malabsorption which manifested as hypoalbuminemia and iron-deficiency anemia and might be also related to gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to worm infestation and ulceration. The presentation of strongyloidiasis with malabsorption has been reported in few case series in the past [3], but not to the severity of malabsorption presented in our patient who had severe anemia (hemoglobin 3.1 gm/ dl) and severe hypoalbuminemia of 6 g/dl.

Our patient then developed severe strongyloides colitis that ended with colonic perforation and secondary peritonitis, which is very rare presentation of strongyloidiasis, particularly in the absence of known risk factors for an immunocompromised state apart from malnutrition, and with the absence of lung involvement by the Strongyloides which is commonly seen in hyperinfection syndrome [7-8].

Diagnosis of strongyloidiasis can be done by stool microscopy and/or serology. The sensitivity of single-stool microscopy is usually around 30% [9]. In our patient, all stool analyses were positive for Strongyloides larva, which indicates a high intestinal worm burden.

Serologic testing is both sensitive and specific, with estimates of 82%– 95% sensitivity and 84%–92% specificity [10-13]. It can be an invaluable diagnostic tool, but it is expensive and not widely available.

A biopsy from affected part of the gastrointestinal tract may demonstrate the larva [14]; in our patient there was heavy infiltration of Strongyloides larva in the resected colon.

Conclusion

Strongyloidiasis is common in certain areas of the world where there is a high risk for potential exposure. Accordingly, a high index of suspension and testing for strongyloidiasis by stool microscopy and serology is mandatory for individuals who come from endemic area and who present with vague or unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms, or for those who present with malabsorption. Testing should also be considered for patients who are intending to start immunosuppressive therapy, because the risk for disseminated strongyloidiasis in this case is very high.

274

References

- Wirk B, Wingard JR (2009) Strongyloidesstercoralishyperinfection in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation..Transpl Infect s 11:143-148.

- Lim S, Katz K, Krajden S, Fuksa M, KeystonJ et al. (2004) Complicated and fatal Strongyloidesinfection in Canadians: risk factors, diagnosis and management.

- Milner, Irvine R A, Barton C J, Bras G, Richards R (1965) Intestinal malabsorption in Strongyloidesstercolarisinfection. Gut 6: 574-581.

- Scowden E B, Schaffner W, Stone W J (1978) Overwhelming Strongyloidiasis: An unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine 57: 527-5.

- Keiser P B, Nutman T B (2004) Strongyloidesstercoralisin the immunocompromisedpopulation. ClinMicrobiol Rev 17:208-2.

- Owor R, Wamukota W M(1976) A fatal case of strongyloidiasis with Strongyloideslarvae in the meninges. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 70:497-499. Lin AL, Kessimian N, Benditt JO (1995) Restrictive pulmonary disease due to interlobular septal fibrosis associated with disseminated infection by Strongyloidesstercoralis. Am J RespirCrit Care Med 151:205-209.

- Nozais JP, Thellier M, Datry A, Danis M (2001) Disseminated strongyloidiasis. Presse Med 30:813-818.

- Al-Hasan M, McCormick, Ribes JA ( 2007) Invasive enteric infections in hospitalized patients with underlying strongyloidiasis. Am J ClinPathol. 128:622-627.

- Loutfy M R, Wilson M, Keystone JS, Kain KC (2002) Serology and eosinophil count in the diagnosis and management of strongyloidiasis in a non-endemic area. Am J Trop Med Hyg 66:749-752

- Carroll SM, KarthigasuKT, Grove DI (1981) Serodiagnosis of human strongyloidiasis by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 75:706-7°

- Neva FA, Gam AA, Burke J (1981) Comparison of larval antigens in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for strongyloidiasis in humans. J Infectis 144: 427-2.

- Savage D, Foadi M, Haworth C, Grant A (1994) Marked eosinophilia in an immunosuppressed patient with strongyloidiasis. J Intern Med. 236:473-475.

- Arsic-Arsenijevic V, Dzamic A, Dzamic Z, Milobratovic D, Tomic D (25) FatalStrongyloidesstercoralisinfection in a young woman with lupus glomerulonephritis. J Nephrol 18:7879