Key words

HIV care, people with HIV, nursing care, nurse students, communication

Introduction

AIDS is a disease with specific characteristics, and it has been considered as a burden that has provoked panic and stigmatization. In contrast to other major epidemics, the HIV epidemic has no rapid rise, obvious peak, or rapid decline. The direct effects of HIV on physical health status are only one part of the problem. There are also social consequences, a secondary epidemic of prejudice, fear, and ignorance. In addition, for HIV-infected people and their families, the psychological distress associated with terminal illness is compounded by social rejection, prejudice, and discrimination [1].

The country’s population, at the end of 2001, was 10,964.020 thousand according to the National Statistical Service of Greece. Over the last 20 years there is an unfavorable situation in terms of the future reproduction of the population with increasing numbers of the elders. According to the data of the Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (H.C.D.C.P.), Greece experienced a substantial upward shift in HIV epidemic after 2004. An increasing trend was also obvious in 2008. More specifically, in 2008, 653 HIV infections were reported, a number that lies within the triad of largest values recorded since the establishment of the HIV/AIDS reporting system. The reported number of infections in 2009, once again, surpassed 600 [2].

In Greece, from the beginning of the epidemic through end of October 2009, there are 9,798 reported cases of HIV infection with 7,881 of these are men, 1,869 women and 98 children. The reported AIDS cases are 3,027 while the reported number of deaths among AIDS cases are 1,613 [2]. In 2010 (by 31/10/2010), 519 new HIV infections were reported. Among them, 451 (86.9%) were males and 68 (13.1%) were females. Totally, 57 cases (11%) reported as HIV positive in 2010 had already developed AIDS or progressed to AIDS during that year. In 2010 (by 31/10/2010), 76 new AIDS cases were diagnosed in Greece. Among them, 61 (80.3%) were males, 15 (19.7%) were females, and 57 cases were reported also as HIV positive in 2010. Sex between men accounted for 56.6% of newly diagnosed AIDS cases, while individuals that acquired HIV infection through heterosexual intercourse represented the 28.9% of cases. Most of the cases were older than 35 years old at the time of AIDS diagnosis. The total number of paediatric AIDS cases remains low in Greece. Οf 37 cases in total, 64.9% have been infected through mother-to-child transmission.

Apart from doctors, nurses are the health professionals who are most actively involved in HIV care in Greece [3]. In general, nurses and nurse students, as they become the practicing healthcare providers of the future, have the greatest direct contact with the blood and the bodily fluids of these patients and are exposed to an occupational risk of HIV infection [4,5].

Education and knowledge about HIV is identified by nurses as the most important factor for the treatment of people infected with HIV in order to avoid misconceptions. Lack of education is identified as one of the major causes of fear, negative attitudes and reluctance to care for people with HIV/AIDS [6]. On the other hand, it is reported that knowledge about the disease and understanding of patients needs, can result in more positive attitudes towards caring people with HIV, increase non-judgmental quality care of these patients, reduce the level of anxiety of nurse students about caring for people with HIV and enhance professional behaviour, attitudes and the delivery of compassionate care by nurses [5,7-9].

A growing body of evidence suggests that level of education, previous experience in caring and marital status are critical factors regarding nurse students’ willingness to care for people with HIV infection [5,7,8]. Furthermore, studies from Britain and the USA linked reluctance to care for people with HIV with fear of contagion and high levels of homophobia among the participating nurse students [6,8].

Up to now, there is limited research evidence regarding nurse students’ perceptions on caring for HIV people in Greece. Therefore, the present study designed to address this lack of knowledge and to enlighten areas of further consideration within the proposed context.

Aim of the Study

The purpose of this descriptive study was to explore nurse students’ perceptions about caring for people with HIV/AIDS, especially in the following areas:

• Nurse students’ attitudes regarding caring for people with HIV

• Communication between nurse students and people with HIV and relatives

• The impact of education in communication between nurse students and people with HIV and relatives

Methodology

This study, in which nurse students were asked about their perceptions about caring for people with HIV/AIDS, was descriptive in nature. Purposive sampling was used by the researchers to recruit the nurse students in the study. The study was conducted in the Technological Educational Institution of Crete (TEI) during the academic year 2009-2010. Nurse students in their senior year of education were consisted the study population.

A proposal was made and permission and access to the field of study was granted by the Head of the Nursing Department of the TEI of Crete. Participants were informed for the purpose of the study and their access to the results by the researchers. The researchers’ availability for clarifications regarding the questionnaire was stated. Ethical considerations were taken into account and voluntary participation to the study was confirmed. Anonymity was emphasised and potential participants assured for confidentiality of their responses. Participants’ rights to withdraw from the study at any time were also stated.

An informed consent form was provided attached to the questionnaire. The questionnaire and the consent form were separated following completion in order to prevent identification of the respondent. Data collection took place by the researchers during clinical sessions at a convenient time for the participants. In order to determine and explore the student’s communication, attitudes and beliefs about HIV, a questionnaire of 21 questions was used including areas of: a) Attitudes towards HIV care, b) Communication with people with HIV and their relatives/friends, and c) Education and communication with people with HIV.

Open-ended and closed-ended questions were included in the questionnaire (3 open-ended and 18 close-ended). Open-ended questions aimed at identifying opinions and views on issues where no previous data existed. Closed-ended questions were used where the participants were offered a list of possible responses on issues with previous knowledge. Participants were allowed to check as many responses as apply. A blank space was provided after the close-ended questions in order to give the opportunity to the participants to provide further specifications or clarifications. Also, an “other” tick box was included, so the participants were not forced to select an answer with which she or he was not completely satisfied.

This questionnaire was developed by the researchers following previous research experience in the area of HIV/AIDS. In particular, similar questionnaires have been used during the implementation of an EC project, namely, “Communicating Health / AIDS”, which was initiated and conducted in five European countries from 1992 to 1997 by the “European Consortium on Health Communication”. Throughout the implementation of this project, research teams specialised in communication and health education developed needs assessment tools and training manuals in collaboration with experts from several European countries. The experience gained from this project led to the development and utilisation of a similar research tool which have been translated and pilot tested for the purposes of the present study 10. Pilot test of the research instrument showed that no further modifications were required. A descriptive statistical analysis was used for data interpretation.

Results

One hundred (100) nurse students participated in the study. The results highlight several factors related to nurse students’ intentions to provide care to HIV-infected people as well as attitudes, beliefs and communication level between nurse students and people with HIV. Demographic data revealed that the participant nurse students were in the sixth (45%) and seventh semester (55%) of their training. The majority of them (84%) were women. The mean age was 25 years old (min. 22- max. 28). Participants stated that they had some basic knowledge on HIV as part of their education.

Nurse students’ attitudes towards HIV care

Results revealed that nurse students were either not very afraid (40%) or not afraid at all (20%) of caring for people with HIV. However, a number of them (40%) stated that were very afraid of providing care to people with HIV. Despite that, the majority of the respondents (60%) reported that they would like to be involved in caring for people with HIV infection after their graduation. When nurse students were asked if they felt anxious by caring for people with HIV in the future, most of them (58%) stated not very anxious, while others stated not anxious at all (28%), or very anxious (14%). Regarding risk perception the majority of nurse students (90%) rated first the probability of infection with the virus. Students pointed out additional aspects regarding risk in caring for HIV people, such as caring for aggressive patients (75%) and implementing nursing interventions (55%).

Communication between nurses and HIV patients and relatives

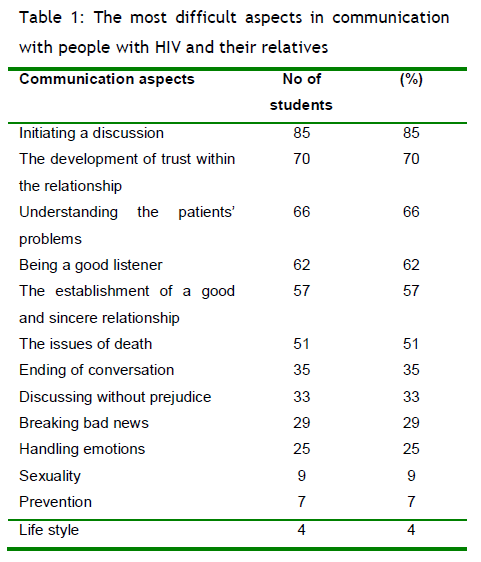

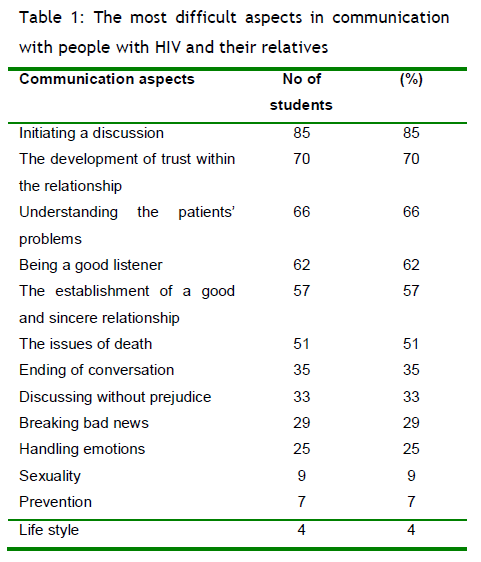

Most of the participants (40%) perceived their role and the initiatives taken by them for communication with their patients either as "important" (40%) or as "very important” (60%). Most of the nurse students (53%) believed that the existing communication between them and their patients is good, very good (36%), moderate (8%), while three of the participants did not answer. The most difficult aspects in communication with people with HIV and their relatives/partners/friends, as reported by the participants, are presented in Table 1.

The most important elements of communication with people with HIV were rated by the participants as follows: psychological support (28%), practising empathy (21%), lack of prejudice (19%), information giving (11%), initiating a discussion (8%), to have an adequate knowledge of the disease (7%), and to be a good listener (6%). Participants also asserted that the hospital facilities and supplies (87%), the environment of the hospital (73%), the increased workload (15%) and the lack of privacy during communication (7%), negatively affect the communication between nurses and patients.

The issues of death (100%), sexuality (47%), prevention (11%) and life style of the patients (8%) were considered as the most difficult aspects in communication with partners, relatives and friends of people with HIV. The situations that are considered to be the most stressful for nurse students when caring for people with HIV are the nursing workload (86%), the contact with the patients (79%), the lack of communication with other health professionals (63%), the disease (49%), the contact with patients’ families (34%) and the lack of organisational support (17%).

Education and communication with people with HIV

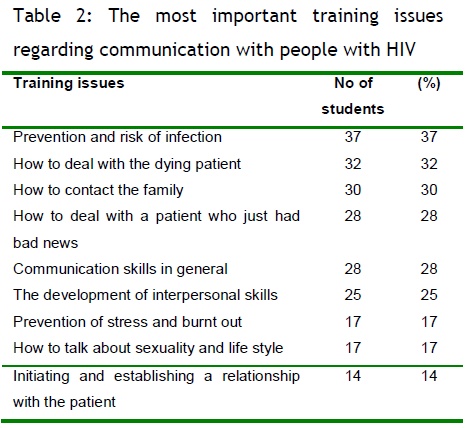

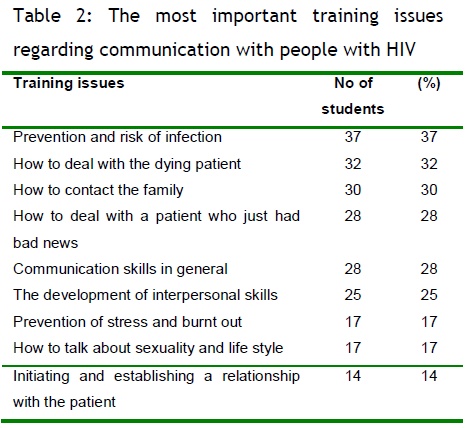

Participants suggested that education is an important factor for improving communication between health professionals and patients (65%), while support of other health care professionals (25%) and good working conditions (20%) were considered essential. The training issues that participants stated as most important regarding communication with people with HIV are represented in Table 2.

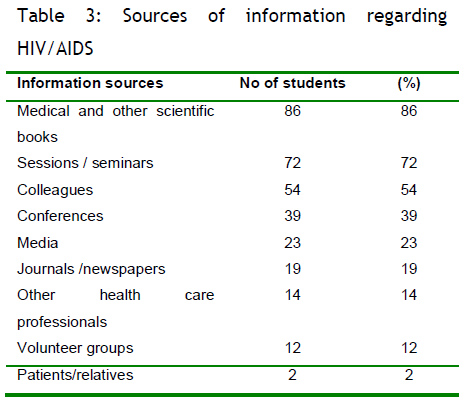

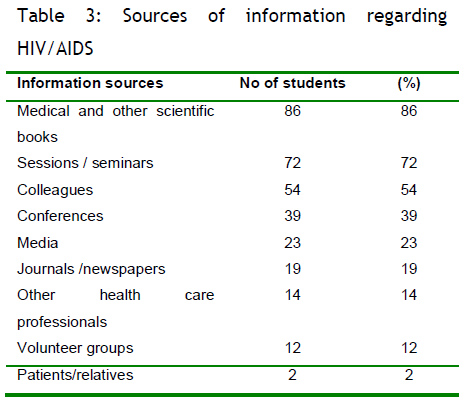

In addition, nurse students referred to information sources that they might use when they have to deal with people with HIV such as scientific books, seminars or colleagues (Table 3).

When the nurse students were asked how training on communication for health care professionals working with HIV people should be organised, they reported that:

"a rotated educational programme should be provided to all nurse students. This programme could be implemented during working days and hours. It is important for all nurse students to be able to participate in this training".

“exchange of scientific information, education, and the development of high skilled health professionals should be the objectives to be attained in a training programme”.

Furthermore,

"the training should include a variety of subjects from ergonomic issues to medical treatment. This way nurses’ care to people with HIV will be improved”.

“all persons who participate in HIV care should have additional and systematic training. The trainers should be highly skilled and very experienced in communication techniques".

Specifically, students stated that they would prefer to be trained by psychologists, doctors or nurses specialised in communication aspects. Also it was reported that systematic education, information giving, and administrative, technical and psychological support were the most important needs for the nurse students who care for people with HIV. The provision of scientific books, formal training, seminars, conferences, and practical experience, as well as the provision of information from experienced health professionals, were considered the most important elements in order to improve students’ communication skills.

Discussion

The findings of the study showed that nurse students’ willingness to provide care for people with HIV depends on factors that are similar to those found by other researchers, such as fear of contagion, appropriate education and communication barriers [5,8,11-15]. It is well established in the literature that those working with HIV people experience considerable psychological stress [9]. In the present study, although the participants reported that the existing communication between them and their patients was very good, it also appeared that they experienced a lot of psychological stress regarding communication issues. Also, the communication between the participants and the partners, relatives and friends of people with HIV was considered to be very stressful, especially when subjects such as death and sexuality were mentioned.

Attitudes on caring and communicating for HIV people have been reported in the literature to be associated with stigma and discrimination [16]. In the present study a number of nurse students reported the issue of prejudice as an element that impedes communication with people with HIV. HIV-related stigma and discrimination are recognized as key barriers both to the delivery of quality services by health providers and to their utilization by community members and health providers themselves. It is well reported that stigma and discrimination by health professionals compromises their provision of quality care, act as a barrier to accessing services both for the general population, as well as health providers themselves, with serious implications for health professionals [17].

In 2009 in a study by Relf, Laverriere, Devlin and Salerno[18], the ethical issues associated with HIV and AIDS were determined by nurse students regarding testing, confidentiality, serostatus disclosure, and the environment of care related to HIV and AIDS in South Africa and the United States. The results showed that in the United States, the attitudes, beliefs, and practices of the nurse students surveyed towards people with HIV and AIDS were not reflective of the ethical values and guidelines relevant to nursing practice with the majority of nurses in South Africa being non-supportive or partially supportive. The research also demonstrated that without exposure to the ethical, legal and psychosocial challenges associated with HIV and AIDS, nurse students, like society in general, may continue to stigmatize individuals living with HIV or AIDS. Consequently, they may enter the workforce ill-prepared for the challenges associated with the epidemic [18].

Relevant literature highlights the importance of providing additional training to health professionals who work with HIV in order to improve knowledge and practice. Most studies reported that after a training intervention, nurses exhibited a high level of skills and knowledge [11,13,14,16,19]. In a study by Reis et al.,[11] who evaluated the discriminatory attitudes and practices by health professionals toward people with HIV in Nigeria, it was found that missed opportunities for prevention, positive living education, and treatment, undermining Nigeria’s concerted national efforts to address the HIV epidemic [11]. These findings also supported by other studies that demonstrated the effect of HIV education on nurses’ attitudes and behavior towards people with HIV in Nigeria, emphasizing that educational programs may also need to address attitudes and cultural beliefs [13,14].

Participants in the present study reported that the environment of the hospital and the hospital facilities negatively affect the communication between nurses and patients. The situations that are considered to be the most stressful for the participants, such as the hospital environment, the increased nursing workload and the lack of privacy, support the findings of similar studies [20,21]. In the same vein, the majority of the participants expressed an interest in additional information and education as a way to result in improvements. Scientific books, seminars, colleagues, conferences, television programmes, and journals and newspapers were the most used by nurse students as information resources regarding HIV. Information sources for the majority of the nurses in the study of Maswanya et al.,[22] were the mass media following by friends and relatives which were the least-reported sources of information [22]. However, more emphasis is placed upon systematically organized education. A relevant study in Greece showed that the majority of the participants believed that they do not have integrate theoretical knowledge and clinical training in order to safely treat people with HIV [23]. The participants of the present study emphasized the need of training regarding communication skills from experienced health professionals and especially by psychologists, doctors or nurses specialised in communication aspects. Similar studies support the above statement by stating the significance of systematic education and the development of highly skilled professionals in HIV care [8,24].

Conclusions and Implication for Research

The present findings have implications for efforts to increase the willingness of nurse students to care for people with HIV. The study showed that although the fear of contagion and psychological stress in communication threatened the students’ willingness to take care of people with HIV and their feeling of well-being on the job, nurse students held positive attitudes regarding caring for HIV people. It appears that further education on HIV/AIDS should place greater emphasis on correcting these misconceptions and overcoming negative attitudes towards people with HIV.

The educational challenge is both attractive and difficult. HIV educational programmes implemented for nurse students need to be evaluated for their impact on the attitudes, knowledge and work practices of nurses who work in the HIV field. There is an extensive communication network between health care professionals which includes community staff, nurses, doctors, social workers, benefit agencies etc. Their support and involvement in educational program planning seems essential in providing an organizational climate conducive to learning and believing the knowledge presented. Also, it is important for all health care professionals to have sufficient information about HIV, to maintain confidentiality and to explore affective issues so they can become aware of their own attitudes as well as the educational needs of others.

There were some limitations in our study that need to be mentioned. Firstly, the sample size was comparatively small, so research evidence has limited representativeness in the general population of nurse students in Greece. Secondly, the research took place in only one peripheral nursing department in the Technological Educational Institution of Crete, and thus generalisability of the findings is not possible. A larger scale effort would be appropriate to determine whether the results reported in this research can be generalized to the broader population of Greek nurse students and whether can produce information for evidence-based practice. Despite these limitations, the present study has important implications for nurse education, practice and research. The results of the study shed some light about nurse students’ perceptions, attitudes and beliefs on caring for HIV people in Greece. Therefore, the study adds to the current knowledge and the results may be of interest to clinical nursing faculty and nurse educators in order to improve the theory and practice of care within HIV context.

Planning of future educational interventions may take into account the modern profile of the health care organizations, the recent developments about HIV and the unique nurses’ roles in order to provide appropriate knowledge and high quality care. Issues of prevention and risk of infection, communication skills interprofessional provision of care, development of interpersonal skills, ethics, prevention of stress and burnt out, attitudes and stereotypes, infection control and confidentiality may be some of the subjects included in future training. Finally, a systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of the educational programmes and the use of advanced teaching strategies may be used for readdressing educational targets and improve training programmes focusing on HIV care.

3349

References

- Kallings LO. The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2008; 263 (3): 218-243.

- Hellenic Centre for Diseases Control and Prevention. Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity. Reporting period: January ? December 2009. Submission date: March 2010. Retrieved from https://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/greece_2010_country_progress_report

- Konte V, Nikolopoulos G, Raftopoulos V, Pylli M, Tsiara C, Makri E, et al. Surveillance of HIV Exposure and Postexposure Prophylaxis Among Health Care Workers in Greece. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24 (4): 337 ? 342.

- Walusimbi M, Okonsky JG. Knowledge and attitude of nurses caring for patients with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. Applied Nursing Research. 2004; 17 (2): 92-99.

- Bektas HA, Kulakac O. Knowledge and attitudes of nurse students toward patients living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV): A Turkish perspective. AIDS Care. 2007; 19 (7): 888-894.

- Earl CE, Penny PJ. Rural nursing student knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about HIV/AIDS: a research brief. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS care. 2003; 14 (4):70-73.

- L?hrmann C, V?lim?k M, Suominen T, Muinonen U, Dassen T, Peate I. German nurse students; knowledge of and attitudes to HIV and AIDS: two decades after the first AIDS case. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000; 31, (3):

- Peate I, Suominen T, V?lim?ki M, L?hrmann C, Muinonen U. HIV/AIDS and its impact on nurse students. Nurse Education Today. 2002; 22 (6): 492-501.

- R?ndahl G, Innala S, Carlsson M. Nursing staff and students attitudes towards HIV-infected and homosexual HIV infected patients in Sweden and the wish to refrain from nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003; 41(5): 454?461.

- Stavropoulou A. Relationships and interpersonal interactions for health care professionals, family and patients within the HIV context. In ?Communicating health/AIDS III-A training package on communication with people with HIV for nurses and social workers?. 1997; pp.135-164. Retrieved from https://www.reso.ucl.ac.be/publications/cee/carecom-en.htm

- 11. Reis C, Heisler M, Amowitz LL, Moreland RS, Mafeni JO, Anyamele C. Discriminatory attitudes and practices by health professionals toward patients with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria. PLOS Medicine. 2005; 2(8): 743-752.

- V?lim?ki M, Makkonen P, Blek-Vehkaluoto M, Mockiene V, Istomina N, Raid U, et al. Willingness to care for patients with HIV/AIDS. Nursing Ethics. 2008; 15 (5): 586-600.

- Uwakwe CBU. Systematized HIV/AIDS education for nurse students at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria: Impact on knowledge, attitudes and compliance with universal precautions. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000; 32 (2): 416-424.

- Ezedinachi EN, Ross MW, Meremiku M, Essien EJ, Edem CB, Ekure E, et al. The impact of an intervention to change health worker?s HIV/AIDS attitudes and knowledge in Nigeria: A controlled trial. Public Health. 2002; 116 (2): 106-112.

- Dimitriadou A, Sapountzi-Krepia D, Psychogiou M, Konstantinidou-Straykou A, Peterson D, Benos A. The identity of the nursing staff in Northern Greece. Health Science Journal. 2008;2(4):206-218.

- Pisal H, Sutar S, Sastry J, Kapadia-Kundu N, Joshi A, Joshi M, et al. Nurses health education program in India increases HIV knowledge and reduces fear. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2007; 18 (6): 32-43.

- Nyblade L, Stangl A, Weiss E, Ashburn K. Combating HIV stigma in health care settings: what works? Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2009; 12 (1): 15.

- Relf MV, Laverriere K, Devlin C, Salerno T. Ethical beliefs related to HIV and AIDS among nurse students in South Africa and the United States: A cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies.2009; 46 (11): 1448-1456.

- Williams AB, Wang H, Burgess J, Wu C, Gong Y, Li Y. Effectiveness of an HIV/AIDS educational programme for Chinese nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006; 53(6): 710-20.

- Laschinger HKS, Finegan J, Shamian J. The impact of workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses' work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Care Management Review. 2001; 26 (3): 7-23. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/hcmrjournal/toc/2001/07000

- Manojlovich M, Laschinger HKS. The Nursing Worklife Model: extending and refining a new theory. Journal of Nursing Management. 2007; 15(3): 256-263.

- Maswanya E, Moji K, Aoyagi K, Yahata Y, Kusano Y, Nagata K, et al. Knowledge and attitudes toward AIDS among female college students in Nagasaki, Japan. Health Education Research. 2000; 15 (1): 5-11.

- Roupa Z, Mylona E, Sotiropoulou P, Faros E, Raftopoulos V, Kotrotsiou S, et al. Knowledge of students training to be health care professionals about AIDS transmission. Health Science Journal. 2007; 1(2):1-8. Retrieved from https://www.hsj.gr/volume1/issue2/issue02_orig04.pdf

- Durkin A. Comfort levels of nurse students regarding clinical assignment to a patient with AIDS. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2004; 25(1): 22-25.