Keywords

Parity; Breastfeeding; Breast cancer; Parous

Introduction

Breast Cancer (BC) is one most diagnosed type of cancers caused cancer death among women worldwide [1]. According to [2] among 12% of all new cancer cases and 25% of all cancers among women is breast cancer. For instance, according to [2] about 22% of cases of breast cancer in Brazil can be prevented by not drinking alcohol, being physically active and maintaining a healthy weight.

Breastfeeding is hypothesized to reduce the risk of BC primarily through two mechanisms, differentiation of breast tissue and reduction of the lifetime number of ovulatory cycles, but previous reviews of the association between breastfeeding and breast cancer have not consistently found that breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast cancer [3]. Among the research works the parity and breastfeeding are controversial issues, particularly in the number of parities and duration breastfeeding [4,5].

Some researchers have been studied the relation between parity and breastfeeding (BF) in preventing Breast Cancer (BC). Their results demonstrated that parity and BF are preventive for BC patients. For example, the role having BF, the number of breastfed children, the period of breastfeeding, age at first lactation, and period of amenorrhea during lactation. Many studies have been proved that breastfeeding is a preventive factor of breast cancer [6-9].

The main goal of this study is to investigate an analysis of the relationship between parity and breastfeeding with breast cancer based on epidemiological researches were published in the reviewed journals between 2010 and 2016.

The rest of this paper is classified as follows; Section 2 reports the used materials and methods. The obtained results from our review comes in Section 3. The finding from our meta-analysis reported in Section 4.

Materials and Methods

In this section, we provide our search method and strategy to select the state-of-art works first. Second, we explain the study selection process in order to extract the relevant works. Third, we report the data abstraction mechanism from the chosen papers. Finally, we explain statistical methods which have been used in our review.

Search and strategy

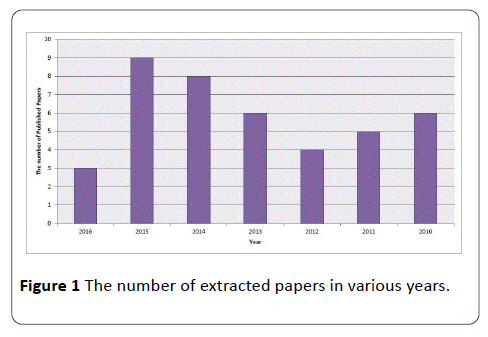

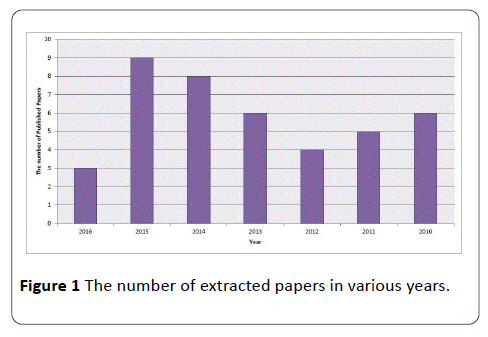

We investigated a comprehensive search on studies on PubMed database du-ring the six-year period between May 1, 2010 and May 1, 2016. Our search is limited to the published researches in English with the following keywords and Medical subjects: (breastfeeding OR breast feed OR lactation) AND (breast) AND (parity) AND (cancer OR tumor OR neoplasm). We also reviewed some additional works for the reference information about the relation between the parity and breastfeeding with breast cancer. In our search results we have selected the following article types; Clinical Trial, Journal Article, and Review. Figure 1 illustrates the number of extracted papers from our research.

Figure 1: The number of extracted papers in various years.

Study selection

We included the studies which had a case-control, cohort, or cross-sectional studies. Then, we investigate the association between the number of parity, duration of breastfeeding in months and incidence of breast cancer. The selected research works had to present the following concepts; i) the hazard ratio ii) odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We discarded the studies that did not provide these information. For some studies which are published in different accommodations we have selected the largest number of cases.

Data abstrction

For each chosen paper we performed an investigation on the eligibility and data abstraction. We extracted the following data from each study; list of authors, the year of publication, the region of study and its design, the size of sample study (i.e., the number of cases and controls and cohorts), duration of study for cohorts, the assessment of study for breastfeeding duration including ever, average, and total months, the number of parities, the study estimates adjusted for the works that have CI greater than 95%. If no adjusted estimates were presented, we included the crude estimate. If no estimate was presented in a given study, we calculated it and its CI 95% according to the raw data presented in the article.

Statistical analysis

The gathered data is calculated as the inverse varianceweighted mean of the natural logarithm of multivariate adjusted RR with 95% CI for breastfeeding and breast cancer risk. We used the random-effects model to consider the within-study and between-study variation [10]. Also, we used The Q test and Thompson [11] to assess heterogeneity among selected literature. Meta-regression has used to assess the potentially important covariate applying substantial impact on between-study heterogeneity [12]. Egger`s regression asymmetry test is used for publication bias [13]. To study the effect of a single study on meta-analysis we use the method in [14-20]. All the statistical analysis were performed with SPSS software on a machine with 4GB of RAM.

Results

The pooled results from our review were reported in this section. We provide a detailed results from each chosen literature here.

Study characteristics

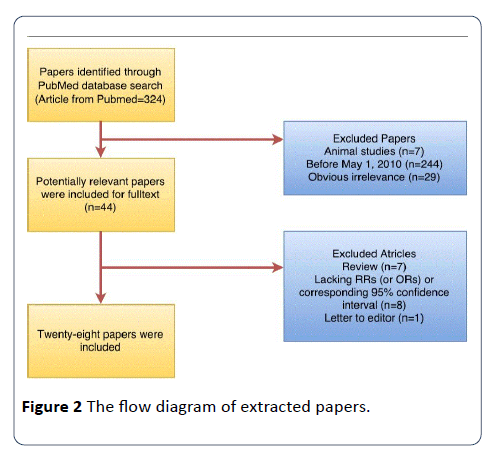

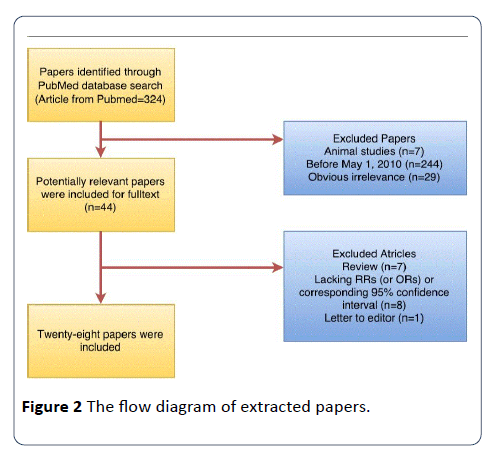

Our search method has identified 324 papers from PubMed. Twenty-eight papers were used in this meta-analysis. Figure 2 shows the steps that we used to extract the papers. In this study, the number of included papers, which demonstrated 12,041 cases, were published between 2010 and 2016. All of the studies only included parous women in analyses. The detailed characteristics of the papers for parity and breastfeeding were shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 2: The flow diagram of extracted papers.

Table 1 Characteristics of our study in parity and breastfeeding effect on breast cancer.

| Reference (year) |

Country |

Study design |

Cases (n) |

Category |

RR (95% CI) |

Adjustment of matched for |

| Akbari et al.[4] |

Iran |

PCC |

376 |

ever versus never |

1.8(0.5-5.5) |

Adjusted for parity, the count of months of breastfeeding, the number of children, tobacco consumption and fatty diet, family history, and use of hormones. |

| De Silva et al.[15] |

Sri Lanka |

PCC |

100 |

> 1 year versus never |

1.74(1.01-3.01) |

Adjusted for breastfeeding, parity,ageatmenarche,menopause, reproductive factors, passive smoking, abortion, alcohol consumption, age, BMI, family history of breast cancer, hormonal contraceptives, use of contraceptives, and level of education. |

| Alsaker et al.[20] |

Norway |

PCC |

2640 |

Not mentioned |

1.32(1.02-1.72) |

Adjusted for long term survival from breast cancer, parity, number of full term pregnancies, age at menarche, martial status, place of residence, BMI, and the effect of Estrogen Receptor (ER). |

| Palmer et al.[19] |

African American |

PCC |

4265 |

Ever versus Never |

1.37(1.06-1.70) |

Adjusted for parity, breastfeeding, estrogen receptor,the number of birth, age at first birth, and family history. |

| Kotsopouloset al. [21] |

seven countries |

PCC |

3330 |

Ever versus Never |

1.37(1.06-1.70) |

Adjusted for a personal and/or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, mutation detection, ages at menarche and menopause, cause of menopause, pregnancy, and breastfeeding history. |

| S. Shinde et al.[22] |

US |

PCC |

2473 |

Ever versus Never |

0.90(0.87-0.94) |

Adjusted for ethnicity, age at menarche, family history, and age at diagnosis. |

| Portoetal.[23] |

Brazil |

PCC |

81 |

Ever versus Never |

2.49(1.175-0.30) |

Adjusted for age at diagnosis, age at menarche, reproductive status, live births, breastfeeding, family history of breast cancer, physical activity, cigarette smoking, body mass index, and metabolic syndrome parameters. |

| Giudici et al.[17] |

Italy |

PCC |

286 |

Ever versus Never |

0.22(0.090-0.59) |

Adjusted for breastfeeding, age at menarche, parity, age at first pregnancy, number of children) with the risk of breast cancers. |

| Redondo et al.[24] |

Spain |

PCC |

501 |

Ever versus Never |

0.25(0.080-0.68) |

Adjusted for lifetime breastfeeding, mean lifetime breastfeeding duration, age at menarche , age atfirst full-term pregnancy, parity, age at diagnosis, age at menopause, menopausal status at diagnosis, the number of pregnancies combined with a long breastfeeding period, number of pregnancies, and family history. |

Table 2 Characteristics of our study in parity and breastfeeding.

| Reference |

Cases |

Controls |

Parity |

Suggested duration of breastfeeding (months) |

| Iqbal et al. [18] |

129 pairs |

NA |

2 |

52.7-55.3 |

| De Silva et al. [15] |

100 |

203 |

1 |

36-47 |

| Kotsopoulos et al. [21] |

3330 |

1665 pairs |

2 |

≥24 |

| Akbari et al. [4] |

376 |

425 |

1-3 |

18-24 |

| Alsaker et al. [20] |

2640 |

NA |

0-3 |

13-19 |

| Giudici et al. [17] |

286 |

578 |

0-2 |

≤12 |

| Palmer et al. [19] |

4265 |

14180 |

≥4 |

not associated |

| Ambrosone et al. [16] |

786 |

1015 |

1-2 |

no additional benefit to ER+ cancer |

Breastfeeding and breast cancer

Twenty-eight papers were used in our meta-analysis. In our meta-analysis, we found that there is an inverse association with the risk of breast cancer of breastfeeding in 11 studies. There was no evidence for this association in seventeen studies. The gathered results suggested that the breastfeeding could reduce the breast cancer risk: summary RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.64132.

Parity, breastfeeding and breast cancer

Eight studies [4,15-21] comprising 12,041 breast cancer cases investigated the association between ever-breastfeeding and breast cancer risk. The obtained results from the researches do not lead us to a unique fact. For example, some works proved that breastfeeding has a positive result on BC [4,15,17,18,20,21]. They also suggested that the duration of breastfeeding should be greater than 13 months. On contrary, some researchers found that there is not an association between the reduction of BC and breastfeeding [16,19-23]. An inverse result was reported in the studies for the association of parity and BC. Among our studies, six papers suggested that at least one parity could reduce the risk of BC while on the rest papers there is no evidence for this risk.

Results

The pooled results from our review were reported in this section. We provide a detailed results from each chosen literature here.

Discussion

The obtained results from the meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies illustrated that ever breastfeeding had a reduction on breast cancer compared with never breastfeeding. There is an inverse association also between longest and shortest duration of breastfeeding in these studies.

The pooled results for the association of parity and reduction of breast cancer showed that the parity could reduce the risk of breast cancer. Some studies suggested that at least one parity could reduce the risk of breast cancer.

Several studies have been done to explain the association of breastfeeding and parity with breast cancer [4,24-36]. For instance, Dall et al. [33] found that parity in younger pregnancies decreases breast cancer risk. A protective effect of parity on breast cancer has been reported in [4,19,34].

This meta-analysis included a large amount of sample cases with a large number of controls. The number of cases in this meta-analysis is 12,031 with 19766 controls. The sample size of this study should have provided enough statistical power to determine the association of ever breastfeeding and never breastfeeding in reducing breast cancer risk. It also could provide sufficient statistical power for the association of parity and the risk of breast cancer. Additionally, this study considered several subgroups to evaluate heterogeneity.

This analysis has several limitations. First of all, as a metaanalysis of observational studies, some studies were prone to biases such as selection bias and inherent in the original studies. Furthermore, some studies are adjusted for fewer factors of breast cancer while some others took many factors into account in studying the risk of breast cancer. In addition, some cohort studies provided detailed information of adjustment their results. Thus, more large studies, especially prospective studies, are needed in the future.

Second, some individual studies may introduce bias in an unpredictable direction. For example, in the case of ever breastfeeding and a longer duration of breastfeeding which are associated with other hormone-dependent or reproductive factors, including lower levels of body mass index [37], the study is adjusted for potential confounding factors.

Finally, the huge heterogeneity and a possible publication bias must be considered in the study, especially, this effect can be seen on the gathered results from ever breastfeeding and the total duration of breastfeeding. In spite of multiple subgroups and their sensitivity analyses that were carried out, heterogeneity still existed in our study. As we found in our analysis, the heterogeneity in our results can be found in the category of duration for the duration of breastfeeding and the number of parities. Therefore, we included the studies that are considered both factors in risk reduction of breast cancer. There is also publication bias in our analysis which can produce a problem for our meta-analysis.

In summary, the result of our analysis suggests that breastfeeding, particularly a longer duration of breastfeeding, was inversely associated with risk of breast cancer. Additionally, having at least one parity could reduce the risk of breast cancer among women.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Arezou Babalou has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

18308

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (2013) Latest world cancer statistics global cancer burden rises to 14.1 million new cases in 2012: Marked increase in breast cancers must be addressed. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Yang L, Jacobsen KH (2008) A systematic review of the association between breastfeeding and breast cancer. J Womens Health 17:1635-1645.

- Akbari A, Razzaghi Z, Homaee F, Khayamzadeh M, Movahedi M, et al. (2011) Parity and breastfeeding are preventive measures against breast cancer in iranian women. Breast Cancer 18: 51-55.

- Tryggvadottir L, Tulinius H, Eyfjord JE, Sigurvinsson T (2001) Breastfeeding and reduced risk of breast cancer in an icelandic cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 154: 37-42.

- Byers T, Graham S, Rzepka T, Marshall J (1985) Lactation and breast cancer: Evidence for a negative association in premenopausal wo-men. Am J Epidemiol 121:664-674.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (2002) Breast cancer and breastfeeding: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50,302 women with breast cancer and 96,973 women without the disease. The Lancet 360: 187-195.

- Yuan JM, Mimi CY, Ross RK, Gao YT, Henderson BE (1988) Risk factors for breast cancer in Chinese women in Shanghai. Cancer Res 48:1949-1953.

- Yang CP, Weiss NS, Band PR, Gallagher RP, White Eet al. (1993) History of lactation and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol 138:1050-1056.

- DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled clinical trials 7: 177-188.

- Higgins J, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21: 1539-1558.

- Higgins J, Thompson SG (2004) Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Statistics in medicine 23:1663-1682.

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315:629-634.

- Aurelio Tobias (1999) Assessing the in uence of a single study in the meta-anyalysis estimate. Stata Technical Bulletin.

- Silva MD, Senarath U, Gunatilake M, Lokuhetty D (2010) Pro-longed breastfeeding reduces risk of breast cancer in Sri Lankan women: A casecontrol study. Cancer Epidemiol 34: 267-273.

- Ambrosone CB, Zirpoli G, Ruszczyk M, Shankar J, Hong CC, et al. (2014) Parity and breastfeeding among african-american women: differential effects on breast cancer risk by estrogen receptor status in the womens circle of health study. Cancer Causes Control 25:259-265.

- Giudici F, Scaggiante B, Scomersi S, Bortul M, Tonutti M(2016) Breastfeeding: A reproductive factor able to reduce the risk of luminal b breast cancer in premenopausal white women. Eur J Cancer Prev Org.

- Iqbal J, Ferdousy T, Dipi R, Salim R, Wu W, et al. (2015) Risk factors for premenopausal breast cancer in bangladesh. Int J Breast Cancer.

- Palmer JR, Viscidi E, Troester MA, Hong CC, Schedin P, et al. (2014) Parity, lactation, and breast cancer subtypes in africanamerican women: Results from the amber consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 106: 10.

- Alsaker MDK, Opdahl S, Asvold BO, Romundstad PR, Vatten LJ (2011) The association of reproductive factors and breastfeeding with long term survival from breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130: 175-182.

- Kotsopoulos J, Lubinski J, Salmena L, Lynch HT, Kim-Sing C,et al. (2012) Breastfeeding and the risk of breast cancer in brca1 and brca2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res 14: R42.

- Shinde SS, Forman MR, Kuerer HM, Yan K, Peintinger F, et al. (2010) Higher parity and shorter breastfeeding duration. Cancer 116: 4933-4943.

- Porto LAM, Lora KJB, Soares JCM, Costa LOBF (2011) Metabolic syndrome is an independent risk factor for breast cancer. Arch GynecolObstet 284: 1271-1276.

- Redondo CM, Nguez MGD, Ponte SM, Castelo ME, Jiang X, et al. (2012) Breast feeding, parity and breast cancer subtypes in a spanish cohort. PloS one 7: e40543.

- Lööf-Johanson M, Brudin L, Sundquist M, Thorstenson S, Rudebeck CE (2011) Breastfeeding and prognostic markers in breast cancer. The Breast 20: 170-175.

- Hardell E, Carlberg M, Nordström M, Bavel BV (2010) Time trends of persistent organic pollutants in sweden during 1993-2007 and relation to age, gen-der, body mass index, breast-feeding and parity. Sci Total Environ 408: 4412-4419.

- Tan HS, Tan MH, Chow KY, Chay WY, Lim WY (2015) Reproductive factors and lung cancer risk among women in the singapore breast cancer screening project. Lung Cancer 90: 499-508.

- Huiyan MA, Henderson KD, Halley JS, Duan L, Marshall SF, et al. (2010) Pregnancy-related factors and the risk of breast carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer among postmenopausal women in the california teachers study cohort. Breast Cancer Res 12:1.

- Bobrow KL, Quigley MA, Green J, Reeves GK, Beral V (2013) Persistent effects of womens parity and breastfeeding patterns on their body mass index: Results from the million women study. Int J Obesity 37:712-717.

- Ahmadinejad N, Movahedinia S, Movahedinia S, Naieni KH, Nedjat S (2013) Distribution of breast density in Iranian women and its association with breast cancer risk factors. Iran Red Crescent Med J 15: 12.

- Mockus M, Prebil L, Ereman R, Dollbaum C, Powell M, et al. (2015) First pregnancy characteristics, postmenopausal breast density, and salivary sex hormone levels in a population at high risk for breast cancer. BBA Clinical 3:189-195.

- Morales L, Garriga CA, Matta J, Ortiz C, Vergne Y, et al. (2013) Factors associated with breast cancer in puertorican women. J Epidemiol Glob Health 3:205-215.

- Dall G, Risbridger G, Britt K (2016) Mammary stem cells and parity-induced breast cancer protection-new insights. J Steroid BiochemMol Biol.

- Sun X, Nichols HB, Tse CK, Bell MB, Robinson WR, et al. (2016) Association of parity and time since last birth with breast cancer prognosis by intrinsic subtype. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25:60-67.

- Connor AE, Visvanathan K, Baumgartner KB, Baumgartner RN, Boone SD, et al. (2016) Abstract lb-363: Breastfeeding, parity and risk of mortality among hispanic and non-hispanic white women diagnosed with breast cancer: the breast cancer health disparities study. Cancer Res 76:LB-363.

- Amadou A, Torres-Meja G, Hainaut P, Romieu I (2014) Breast cancer in Latin America: Global burden, patterns, and risk factors. Saludpublica de mexico56: 547-554.

- Wojcicki JM (2011) Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: A review of the literature. J Womens Health 20: 341-347.