Short Communucation

Sometimes, health promotion and workplace health promotion have been criticized as being vague because of less theoretical anchorage and little evidence of usefulness in research and practice. In text below theoretical descriptions of the concept of health are displayed, as well as: health promotion, workplaces health promotion, empowerment, and example of research results which might help development, implementation and evaluation of an intervention to prevent illness and promote health.

Health in the light of Ill Health

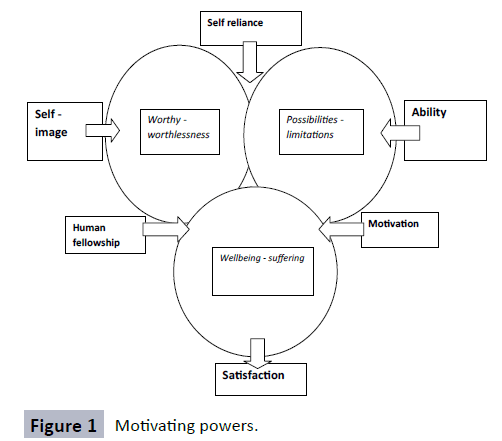

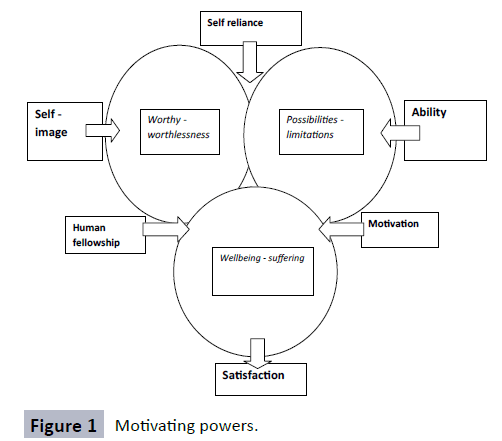

The most people do not reflect about health until they are affected with some form of illness. Therefore, an understanding of the meaning of health is essential when considering workplace health promotion. Antonovsky [1] stated that ”health is a movement from a healthy to a pathogenic pole on a continuum”. A phenomenological study [2,3] resulting from 25 qualitative interviews showed that health included two contrasting identities of experiences. One identity is characterized by vital force, implying health, whereas was distinguished the other by powerlessness, implying ill-health. These different experiences are created through a positive or negative self-image, varying ability in overcoming obstacles and the level of satisfaction with life. The self-image and the ability are connected through self-reliance where the positive self-image and a strong ability strengthen self-reliance. On the other hand the ability and the satisfaction are unified in the motivation to change the life-style. Motivation increases when the ability to manage the situation gives healthy outcomes, thus resulting in individual’s satisfaction with life. Finally, the satisfaction and the self-image are reliant on human fellowship to develop human characters. Thus, the meaning of health is determined in vital force, where self-reliance, motivation and fellowship are the motivating powers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Motivating powers.

According to the interviews experiences, the vital force equals health in cases were individuals respect themselves, have the ability to manage different situations and are able to enjoy the pleasure in life. The vital force releases strength in order to improve health even in difficult situations. Powerlessness, however, is displayed through negative self-image, limitations and suffering, thus the individuals become dissatisfied with themselves and their whole life. In such situation destructive feelings prevail and the individual’s autonomy and whole existence are threatened. The experiences of vital force and powerlessness are intertwined in a dialectic pattern, which implies that health can vary from situation to situation depending on which experiences are currently dominating. The relationship between health and ill-health includes the sense of being worthy as opposite to worthless, possibilities versus limitations and well being in contrast with suffering. The participants experienced health when the advantages of values, possibilities and well being outweighed the disadvantages of valueless, limitations and suffering.

Health Promotion and Workplace Health Promotion

At the initial conference of health promotion, held in Ottawa 1986, a charter aimed at achieving health for all, was introduced. This charter states: “Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and improve their health”. An individual or a group must be able to identify and realize efforts to satisfy identified needs, and also to change or cope with the environment. Therefore, health is seen as a resource for everyday life, not the objective of life. Health is a positive concept that emphasises social and personal resources as well as physical capacities. Health promotion does not solely involve the responsibilities of the health sector, but reaches beyond healthy lifestyles toward wellbeing. Improvement in health requires fundamental conditions and resources for health, including peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice, and equity. Prerequisites for health promotion actions comprise the key words advocate, enable, and mediate. These actions strive towards making political, economic, social, cultural, environmental, behavioral, and biological factors advantageous, through health advocacy. The aim is to reduce the differences in current health status, and to increase equal opportunities and resources, thereby enabling all people to reach their fullest health potential. Adequate health promotion needs coordination by governments along with health, social, and economic sectors, and also nongovernmental and voluntary organizations, local authorities, industry, as well as the media. Professionals and social groups have certain responsibility to mediate between different interests in society in the pursuit of health. Health promotion actions involve the formulation of a healthy public policy, creating supportive environments, strengthening community actions, developing personal skills, and the reorientation of health Services [4].

“Health is created and lived by people within settings of their everyday life; where they learn, work, play and love” [4]. Consequently, a workplace is a setting where workplace health promotion may be initiated and perceived as a resource for the employee and the organisation. According to the Luxembourg Declaration, workplace health promotion includes efforts of employers, employees, and society to improve the health and wellbeing of people at work. These goals are attained by combining an improved work organization with an improved work environment, and by promoting active participation and encouraging personal development, not only in theory, but actually also in practical programs. A healthy work environment is a social process, and is a result of actions taken by various stakeholders and outside enterprises. Leadership and management practices, based on a participative culture, are the vehicles of this process. Decisionmakers’ strategies and policies, quality of work environment and organisation of work as well as personal health practices determine healthy workplaces. Healthy work environments contribute to the protection of communities' and populations' health and also improve social and economic development at a local, regional, national, and European level. Workplace health promotion may attain the label “healthy people in a healthy organisation” if all staff members are involved; the promotion is integrated into all important decision-making in all areas of work and in all areas of the organisation; and if all measures and programs are oriented toward problem-solving models, containing individually as well as environmentally directed measures. In terms of the latter, it should involve a combination of risk reduction strategies and development of protection factors and health potentials [5].

Empowerment as a Part of Workplace Health Promotion

The concept of empowerment is close related to workplace health promotion. Balance between individual and organisational action is necessary for attaining community capability at workplaces. Empowerment is an act that exists in relation to power. In professional practice, power is defined as “power over” and “power with”. “Power over” depicts the reality of matters such as disease, health behavior, and risk factors, while “power with” refers to the reality of lived experience in the language, images, and symbols that people use [6]. Empowerment entails both psychological and community empowerment as well as empowered organisations. Psychological empowerment includes personal trust, personal development, and a willingness to participate in collective activities and organisations. In general, community empowerment means that people experience more control over decisions that influence their health and lives. It includes political, collective, and social action, as well as psychological empowerment. Empowered organisation refers to activities within an organisation that generate psychological empowerment, fend off threats from society, improve the quality of life, and that facilitate the participation of the citizens [7-9]. Research has focused on the individual level of empowerment rather than on structures, processes, and outcomes on the organisation and community levels. Organisational empowerment refers to efforts that generate psychological empowerment among the stakeholders and that lead to effectiveness in achieving organisational goals. Empowered organisations comprise intra-organisational, inter-organisational, and extraorganisational components. The intra-organisational components concern characteristics of internal structure and the functioning of the organisation. These components provide the infrastructure for stakeholders, allowing them to engage in the pro-active behaviour necessary for goal achievement. Inter-organisational empowerment creates links between organisations, and refers to relationships and collaboration across boundaries. The extraorganisational components refer to organisational action taken in order to affect larger environments that the organisation is part of, and represent organisational efforts to exert control. Examples of such action include policy changes, the creation of alternative services, and successful promotions [10].

Accordingly, empowerment can be defined as an individual strength that, in alliance with other participants within the collective, yields the ability to influence the organization from a bottom-up perspective. This is a central aspect of health promoting workplaces, and plays a significant role in employees’ job satisfaction, organisational commitment, job performance, and stress reduction [11]. The effectiveness of empowerment strategies is recognized by improved health and reduced health disparities. Much research has focused on empowerment of socially excluded populations [12]. Nonetheless, a review of Nordic research from 1986 to 2008 disclosed that intervention studies focused on preventive medicine rather than on health promotion as defined by the Ottawa Charter [4]. Many of the studies had an individual focus, in terms of changing employees’ lifestyles or behaviors by using a top-down approach, avoiding settings-related factors and the empowerment of employees [13].

Several health promoters exert power over the community through “top-down” programs, at the same time using the discourse of the Ottawa Charter. This creates a tension between the discourse and the practice, as little attention is paid to the methods by which empowerment can be put into operation in top-down programs. Two different discourses co-exist in health promotion. The conventional discourse focuses on diseaseprevention by means of lifestyle management, or control of infectious diseases. A more radical discourse emphasises social justice through the community, by empowerment, and advocacy. This discourse uses a bottom-up approach, while the conventional discourse, with health promoting programs, utilizes a top-down approach. Top-down programs comprise an overall design; setting of objectives; strategy implementation; management; and program evaluation. In bottom-up programs, the outside agent assists the community in identifying issues that are relevant to the employees’ lives, enabling them to develop strategies for resolving these issues. The designer and the management negotiate with the community, and extended time is often required for planning this type of program [9].

Empowerment strengthens sustainable health-promotion actions, because it holds the capacity to maintain the benefits for communities and populations beyond the initial phase of implementation. These actions may well continue despite the limits of finances, expertise, infrastructure, natural resources, and participation of stakeholders. Sustainable health promotion strategies are compatible with the natural environment in which they are delivered, and do not lead to unintended threats to the health of future generations [14].

Development, Implementation and Evaluation of an Intervention

Laverack and Labonte [9] argue that in the context of top-down programs, an empowerment “parallel track”, running alongside the conventional program, reinforces community empowerment, integrating goals into the organisation. A parallel track comprises five components: 1) Strategic and participatory planning that involves the participants and increases the empowerment in the program design. 2) Program objectives, albeit varying, reflected in empowerment objectives and outcomes. 3) A strategic approach to empowerment involving the formation of small groups; the development of community organisations; the strengthening of inter-organisational networks; and political action. 4) Feasible and practicable methods for strategic planning and evaluation of the management and implementation of community empowerment programs. 5) Process-oriented assessment rather than assessment of any specific outcome, where the process itself constitutes the outcome [9].

Shaping a learning culture at the workplaces is a prerequisite for a successful implementation of an intervention. A learning culture rises when everybody at the workplaces are willing to teach, learn and communicate about their own competencies without guarding territories [15]. In a grounded theory study about promoting fracture prevention activities patient-centered interactions and face-to-face collaborations are examples of actively shaping a learning culture. Patient-centred interaction entails breaking down traditional expertise patterns in the form of information and medical investigations and changing communication patterns with the employee into a more coachlike interaction. Setting up empowering meetings at workplaces raises the employees’ awareness and yields new ideas of how to support the patient. Face-to-face collaboration visualises existing prevention links and identifies obstacles and opportunities for applying a comprehensible preventive and supportive approach. This approach builds a sense of possible prevention due to employees’ experiences of coherence, loyalty, and pride of the community [16]. Below follow two bottom-up approaches that may be interpreted as parallel tracks. Hjalmarson, Åhgren and Strandmark [17] published a study on an inter-professional collaboration in a qualitative and quantitative, longitudinal case that concerned secondary prevention for patients with osteoporosis. Qualitative data were collected from documents as well as from field notes written down during workshops and learning circles. Statistical and quantitative data were retrieved from a register, and were scrutinised through telephone interviews. A content analysis was conducted on the qualitative and quantitative data, while the data from the register were statistically analysed. Four themes emerged, relating to structure, process, outputs, and outcomes of the inter-professional collaboration. The structure of the bottom-up approach displayed a horizontal composition and allowed professionals freedom to act and an evolving leadership style. The process demonstrated continuous feedback, which activated inter-professional motivational forces. The output disclosed inter-professional innovations and shared values. The outcome was inter-professional transparency and collective control. The four themes were generated by data source triangulation. Inter-professional collaboration was facilitated by a bottom-up structure that stimulated innovative processes for secondary prevention. A structure where leaders and coworkers develop interdependency requires focus on interprofessional interaction. Measuring collective performance and applying inter-professional motivational forces appeared to be imperative steps. Nonetheless, some top-down actions were observed in the inter-professional collaboration, e.g. provision of resources; collaborative support; sustained, evidence-based work; and continuous feedback. In summary, a balance between bottom-up and top-down structures triggered improvements in inter-professional collaboration.

Strandmark and Rahm [15,18] developed, implemented, and evaluated a process for preventing and combating workplace bullying. The research project followed a community-based participatory approach. Data were collected through individual interviews and focus group interviews and analyzed using Grounded Theory methodology. The interventions and the implementation comprised: one half-day seminar on the definition of bullying, feelings of shame, conflict management, and communication; playing cards in small groups; developing an action plan; presentation and discussion of the action plan among the managerial groups; and finally, a discussion about whether the implementation process had succeeded or not. The analysis showed that the immediate supervisors, in collaboration with coworkers and the upper management were in the best position to counteract and combat bullying. The goal “zero tolerance toward bullying” was attainable if all involved worked together to apply humanist values, an open atmosphere, group collaboration, and conflict resolution. The evaluation after implementation revealed that employees had become more aware of bullying problems; the atmosphere in the workplace had improved; collaboration between and within groups had become stronger; and supervisors now worked continually to prevent and combat bullying and upheld humanist values, as suggested. A participant said: “You had good training. It gave you strength and made you very capable.”

Systematic efforts to implement the complete action plan and conflict resolution system were, however, missing. Some coworkers were disappointed that upper management appeared not to involve themselves in workplace issues. Although the researchers informed upper management about their findings on three separate occasions, this appears to have been insufficient. It might have been advisable to invite the organisational leaders to the lectures and the training sessions.

Conclusions

Workplace health promotion, in which empowerment plays central, includes individual and organisational contexts as well as practical and theoretical ones. Employees and upper management need to become genuinely involved in workplace health promotion. Both, top-down and bottom-up strategies are necessary to be balanced in order to create health-promoting workplaces, since individuals as well as organisations are involved. Arenas for dialogue and reflection in connection with empowerment create the conditions for sustainable workplaces. A learning culture, parallel tracks and participation facilitate implementation of an intervention.

17791

References

- Antonovsky(1986)Unraveling the mystery of health. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

- Strandmark MK (2004) Ill health is powerlessness: a phenomenological study about worthlessness, limitation and suffering. Scand J. Caring Sci18: 135-144.

- Strandmark MK (2006) Health means vital force – a phenomenological study on self-image, ability and zest in life. VardiNorden26: 42-47.

- World Health Organization (1986) The Ottawa Charter for health promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion, 21 November 1986, WHO regional office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark, Ottawa.

- European Network for Workplace Health Promotion (ENWHP) (2007) Luxembourg Declaration on Workplace Health Promotion in the European Union 1997/2007, Luxembourg.

- Labonte R (1994) Health promotion and empowerment: Reflections on professional practice. Health Ed Quart21: 253-268.

- Zimmerman MA, Rappaport J (1988) Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. Am J Com Psych 16: 725-750.

- Rissel C (1994)Empowerment: the holy grail of health promotion? Health Prom Int 9: 39-47.

- Laverack G,Labonte R (2000) A planning framework for community empowerment goals within health promotion. Health Pol Plan 15: 255-262.

- Petersen NA, Zimmerman MK (2004) Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. Am J Com Psych 34: 129-145.

- Butts MM, Vandenberg RJ, Del Joy DM, Schaffer BS, Wilson MG, et al. (2009) Individual reactions to high involvement work processes: Investigating the role of empowerment and perceived organizational support. J Occup Health Psych2: 122-136.

- Wallerstein N (2006)What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? WHO Regional Office for Europe’s Health Evidence Network (HEN), Copenhagen.

- Torp S, Eklund L,Thorpenberg S (2011)Research on workplace health promotion in the Nordic countries: a literature review, 1986-2008. Glob Health Prom18: 15-22.

- Smith BJ, Tang KC, Nutbeam D (2006) WHO Health Promotion Glossary: new terms. Health Prom Int 21: 340-345.

- Strandmark MK, Rahm G,Wilde-Larsson B, Nordström G,Rystedt I, et al.(2016) Preventive strategies and processes to counteract bullying in health care settings: Focus Group Discussions. IssMent Health Nurs.

- Hjalmarson HV, Strandmark MK (2012) Forming a learning culture to promote fracture prevention activities. Health Ed112: 421-435.

- Hjalmarson HV,Ahgren B, Strandmark MK (2013) Developing interprofessional collaboration: A longitudinal case of secondary prevention for patients with osteoporosis. J Interprof Care27: 161-170.

- Strandmark MK,Rahm GB (2014) Development, implementation and evaluation of a process to prevent and combat workplace bullying. Scand J Publ Health 15: 66-73.