Introduction

Head and neck cancers comprise a heterogeneous group of mostly squamous cell carcinomas that arise in the mucosal surfaces of the upper aerodigestive tract and primarily affect the oral cavity (lips, front two-thirds of the tongue, gingivae, buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth, hard palate, and the small area behind the wisdom teeth); the salivary glands; the nasal cavity and the paranasal sinuses; the pharynx, i.e., nasopharynx (the upper part, behind the nose), oropharynx (the middle part, including soft palate, base of the tongue, and tonsils), and hypopharynx (the lower part); and the larynx [1].

Head and neck cancers are highly curable if detected early [2], usually by some form of surgery, although chemotherapy and/ or radiation therapy are also employed [2,3]. Still, these malignant neoplasms are among the most difficult to manage. Firstly, a significant number of patients presents with regional lymph node involvement and metastatic disease [2,3], making complete eradication of the tumor difficult. Furthermore, even successful therapy may leave patients with major functional deficits and significant loss of quality of life [2,3]. In addition, 10 to 20% of initially cured patients develop second primary malignancies within 20 years [4].

With approximately 650,000 new cases per year, head and neck cancers account for about 6% of the global burden of cancer and represent the sixth most common malignancy worldwide [5]. These tumors are endemic in a few well-defined populations, which is presumably associated with the relative distribution of risk factors. The most important ones are probably extensive use of tobacco and high consumption of alcohol, which account together for 75 to 85% of cases [6,7]. Other risk factors are the chewing of betel quid [8]; the consumption of diets rich in salted, fermented, or otherwise preserved meat and fish but poor in fresh fruits and vegetables [9]; occupational exposure to nickel, asbestos, wood dust, paint fumes, and gasoline fumes [10,11]; and infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV; [12]) and the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV; [13]).

The Republic of Suriname (South America) harbors a culturally, religiously, and ethnically highly diverse population of approximately 500,000 [14,15]. A cross-sectional study among 4,400 households found 38.4% of males and 9.9% of females between 12 and 65 years of age to be active cigarette smokers [16]. An earlier survey in individuals of 15 years and older had revealed a relatively high per capita cigarette consumption of 1,870 per year [17]. Furthermore, an assessment of the alcohol consumption in a similar age group had disclosed an annual per capita intake that was equal to the world average of 6.2 L pure alcohol [18], and an average drinking pattern that was associated with a higher morbidity and mortality [19]. In addition, the relatively high cervical cancer incidence of more than 20 per 100,000 women per year [20] not only position Suriname among the middle- to high-risk regions for this malignancy [20] but suggests also that infection with certain oncogenic HPV strains may play an important role in the development of responsive neoplasms [21,22].

Considering the multi-factorial etiology of head and neck cancers involving an interplay of, among others, life-style-related and viral factors, the above-mentioned data raise the possibility that these malignancies may represent an important health problem in Suriname, warranting preventive measures. So far, no studies addressing this topic have been done. For this reason, we determined incidence rates of this group of tumors in Suriname for the period between the years 1980 and 2004. The data obtained have been stratified according to anatomical site, as well as patients’ gender, age at the time of diagnosis, and ethnic background, and have been compared to those reported for low- and high-incidence areas throughout the world.

Patients and methods

Study population

In this study, the histopathologically confirmed head and neck malignancies registered in Suriname between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2004 have been inventoried and stratified on the basis of location as well as gender, age at the time of diagnosis, and ethnic origin. Benign lesions and in situ carcinomas of the head and neck region have been excluded from the study. The same applied to cancers of the brain, eye, and thyroid; those of the scalp, skin, muscles, and bones of the head and neck; as well as affected lymph nodes in the head and neck region [1].

Sources of data

Relevant patient data were obtained from the Pathologic Anatomy Laboratory of the Academic Hospital Paramaribo, the referral center for histopathological cancer diagnosis and cancer registration in Suriname. Cancer cases are classified using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, second edition [23]. Patients’ records include, among others, histopathological diagnosis, gender, date of birth, as well as ethnic origin, and have been treated confidentially.

Population data, including estimates of the total mid-year resident population of Suriname for each year covered by this study, were provided by the Section Population Statistics of the General Bureau of Statistics from the Ministry of Planning and Developmental Cooperation [14,15]. Estimates of the male and female mid-year resident populations were derived from the total mid-year resident populations based on reports mentioning that males represented 50.3%, and females 49.7% of the Surinamese population [14].

Data analysis

For each year between 1980 and 2004, numbers of overall head and neck cancers as well as numbers of cancers from the individual sites have been determined for males and females; for cases aged between 0 and 19 years, between 20 and 49 years, and 50 years and above; as well as for the three main ethnic groups, viz. Creole (those from mixed black and white ancestry; [15]), Hindustani (those from Eastern Indian origin; [15]), and Javanese (those originating from the Indonesian island of Java; [15]). These groups comprise approximately 31, 37, and 15%, respectively, of the total Surinamese population [14]. For each (sub-)stratum, average yearly numbers of cases as well as average yearly crude and sex-specific incidence rates were calculated. The latter were calculated by dividing the number of cancer cases for each (sub-)stratum by either the estimated total mid-year population or the estimated mid-year male or female population, and were expressed per 100,000 population, or per 100,000 men or women, respectively.

Statistics

Data presented are means ± SDs and have been compared using ANOVA and Fisher’s exact test, taking P values < 0.05 to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Overall data

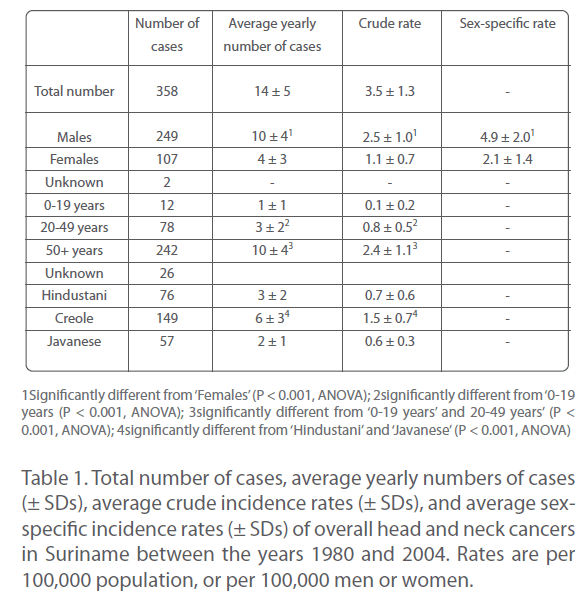

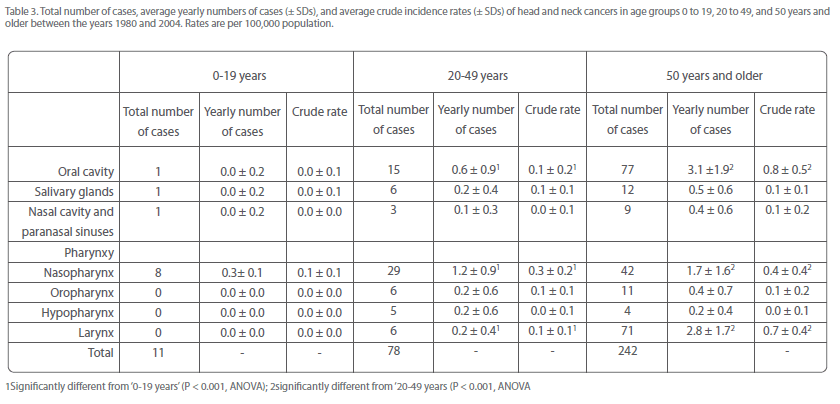

Between the years 1980 and 2004, a total of 358 individuals was newly diagnosed with a malignancy of the head and neck region (Table 1). This was consistent with about 15 new cases per year (or roughly 1 per month) and an overall crude incidence rate of about 3.5 per 100,000 population per year (Table 1).

Table 1: Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (±SDs), average crude incidence rates (± SDs), and average sexspecific incidence rates (± SDs) of overall head and neck cancers in Suriname between the years 1980 and 2004. Rates are per 100,000 population, or per 100,000 men or women.

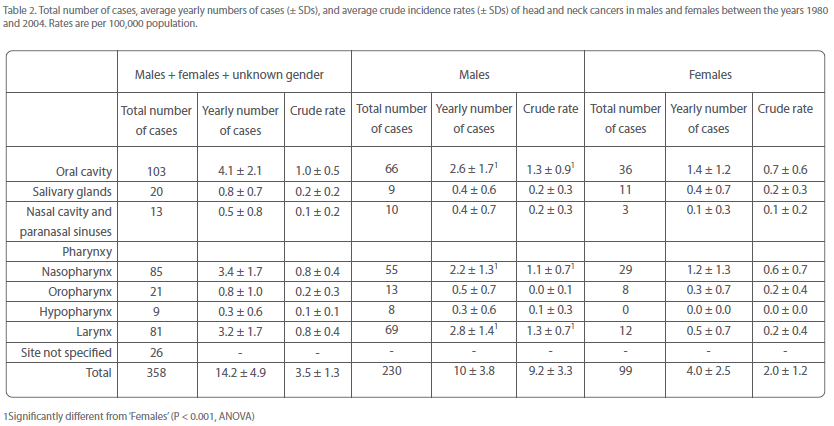

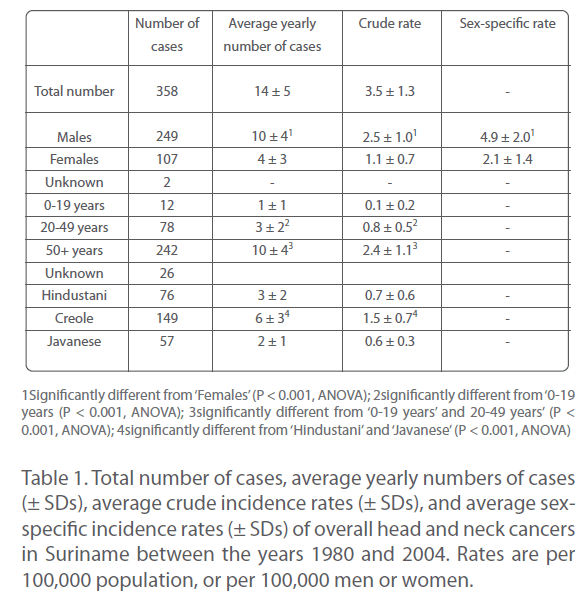

The most frequently affected anatomical sites in the period covered by this study were the oral cavity, nasopharynx, and larynx, comprising together approximately 75% of the total number of head and neck cancers (Table 2). Individually, these cancers accounted for approximately 29, 24, and 23%, respectively, of overall head and neck malignancies (Table 2). Tumors of the salivary glands, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, oropharynx, and hypopharynx constituted approximately 6, 4, 6, and 3%, respectively, of overall head and neck cancers.

Table 2: Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (± SDs), and average crude incidence rates (± SDs) of head and neck cancers in males and females between the years 1980 and 2004. Rates are per 100,000 population.

Incidence of head and neck cancers by gender

Approximately 70% of patients was male, about 30% female (Table 1). This corresponded to average rates of roughly 10 male and 4 female cases per year (Table 1), or 5 men and 2 women per 100,000 per year. Apparently, head and neck cancers arose.

Table 1. Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (± SDs), average crude incidence rates (± SDs), and average sexspecific incidence rates (± SDs) of overall head and neck cancers in Suriname between the years 1980 and 2004. Rates are per 100,000 population, or per 100,000 men or women.

Approximately 2.5 times more often in Surinamese men than in Surinamese women.

Oral cavity, nasopharynx, and larynx were also the most frequently affected sites in both men and women, together accounting for around three-quarters of the total number of head and neck cancers in each gender (Table 2). Oral cavity and nasopharyngeal cancer were almost twice more common in men than in women, but laryngeal cancer was nearly 6 times more often diagnosed in men than in women (Table 2). Thus, the male-over-female excess of overall head and neck cancers must be mainly attributed to the over-representation of laryngeal cancer in men.

The remaining head and neck cancers occurred in both men and women at average rates of at the most once every two years.

Incidence of head and neck cancers by age

In the 25 years covered by this study, about 3% of overall head and neck cancers was seen in individuals of 19 years or younger, approximately 22% in those aged between 20 and 49 years, but almost 70% in those of 50 years or older (Table 1). This corresponded to about 1 case per year in age group 0 to 19 years, 3 per year in age group 20 to 49 years, and 10 per year in age group 50 years and older (Table 1). Thus, the occurrence of overall head and neck cancers in Suriname was highly age-dependent, incidence rates strongly increasing with increasing age.

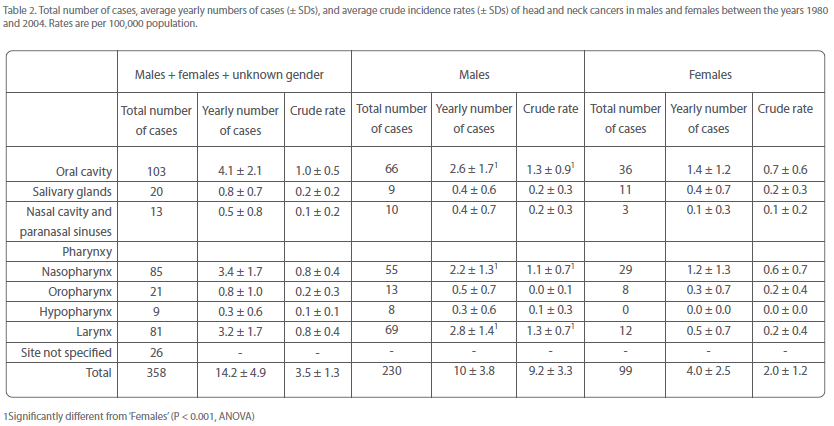

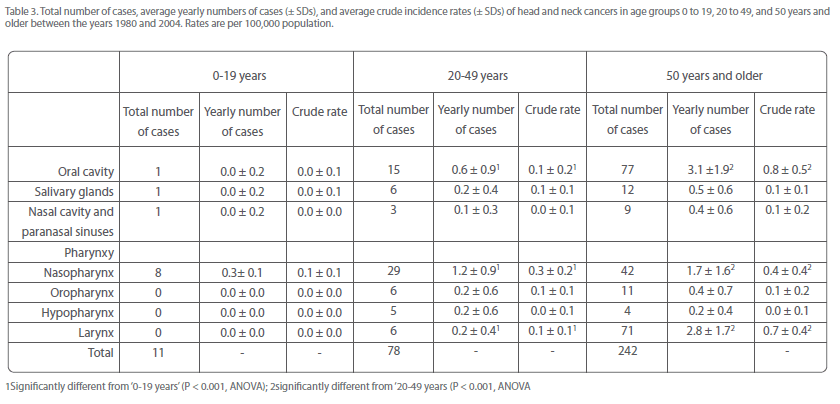

Incidence rates of most individual head and neck cancers increased also with increasing age

This was particularly evident for the most numerous sites, i.e., oral cavity, nasopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancer (Table 3). Together, these malignancies constituted about 3% of all head and neck cancers in age group 0-19 years, and increased to 14% in age group 20-49 years, and subsequently to 53% in age group 50+ years (Table 3).

Table 3: Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (± SDs), and average crude incidence rates (± SDs) of head and neck cancers in age groups 0 to 19, 20 to 49, and 50 years and older between the years 1980 and 2004. Rates are per 100,000 population.

Notably, there were much more cases of oral cavity and laryngeal cancer in patients of 50 years and older (approximately 75 and 90%, respectively, of the total number) than in those younger than 50 years (Table 3). On the other hand, the number of nasopharyngeal cancers in individuals of 50 years and older was only slightly higher than that in those younger than 50 years (49 and 44%, respectively; Table 3). This suggests that the appearance of nasopharyngeal cancer was to a lesser extent determined by older age than oral cavity and laryngeal cancer.

Incidence of head and neck cancers by ethnic background

Approximately 80% of all head and neck cancers (282 of the 358 cases) were diagnosed in representatives of the three largest ethnic groups, viz. Hindustani, Creole, and Javanese (Table 1). More than half of them (about 54%) was Creole; the remainder was more or less evenly distributed between Hindustani and Javanese (Table 1). Frequencies were about 6, 3, and 2 cases, respectively, per year, and crude incidence rates were approximately 1.5, 0.7, and 0.6 per 100,000 population per year (Table 1). Thus, head and neck cancers seemed to occur approximately 2.5 times more often in Creole than in Hindustani and Javanese, and as often in the latter two groups.

Oral cavity, nasopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancer were the most numerous cancers in Creole, occurring at rates of 1 - 2 cases per year (Table 4). In Hindustani, oral cavity and laryngeal cancer also stood out, arising at mean frequencies of 1 case per year (Table 4), while nasopharyngeal cancer was significantly less common in this group (Table 4). In Javanese, on the other hand, the latter cancer was most numerous, constituting almost two-thirds of the total number of head and neck cancers in this group (Table 4). Notably, approximately three-quarters of oral cavity and laryngeal cancers were seen in Hindustani and Creole, while 40% of nasopharyngeal cancers manifested in Javanese (Table 4). All these observations hint that these malignancies might have a predilection for certain ethnic groups.

Table 4: Total number of cases, average yearly numbers of cases (± SDs), and average crude incidence rates (± SDs) of head and neck cancers in Surinamese Hindustani, Creole, and Javanese between the years 1980 and 2004. Rates are per 100,000 population.

Discussion

The scale of cigarette smoking [16,17], the pattern of alcohol consumption [18,19], and the incidence of HPV-related diseases such as cervical carcinoma [20,24], raise the possibility that head and neck cancers are important public health concerns in Suriname. However, evaluating data from Suriname’s national cancer registry between the years 1980 and 2004, the results from this study suggest that the incidence profiles of these malignancies in the country approximate those of low-risk regions throughout the world.

This conclusion is based on the relatively low rate of overall head and neck cancers in Suriname of 4 per 100,000 population, which is close to that of 3.2 or less per 100,000 associated with low-incidence areas [25]. Furthermore, with around 15 new cases per year, head and neck cancers comprised about 5% of the roughly 300 new overall malignancies that are yearly diagnosed in Suriname [20,24], and were the sixth most common group of malignancies in the country [20,24]. These data are in line with average global statistics for this group of cancers [5,26], indicating that the burden of head and neck cancers in Suriname did not differ substantially from values that are encountered in the rest of the world.

Of note, with 2 - 3 per 100,000 men, and 1 or less per 100,000 women per year, frequencies of the most common sites - oral cavity, nasopharynx, and larynx – were lower than, or comparable to the global averages of 3.2 - 6.3, 0.8 - 1.9, and 0.6 - 5.1, respectively, per 100,000 men or women per year [5]. Furthermore, the incidence rates of these tumors found in this study were considerably lower than those noted for high-risk regions. Examples of such regions are South-Central Asia and parts of Europe, where oral cavity cancer rates in males and females exceed 10 and 8, respectively [5,25,27,28]; southern China as well as South-east Asia, North Africa, and Alaska, with rates of nasopharyngeal cancer of 10 - 20 in men and 5 - 10 in women [5,25,28,29]; and eastern Europe and South America, where laryngeal cancer rates in men and women are over 7 and 1, respectively [5,25,28,30]. These data provide additional support for the characterization of Suriname as a low-incidence country for head and neck cancers.

The 2- to > 5-fold male-over-female excess of overall head and neck cancers as well as oral cavity, nasopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancer, is in accordance with international trends indicating that these tumor types occur 2 - 4 times more often in men than in women [26]. These observations may be attributed to a greater exposure of men than women to risk factors such as cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and/or occupational hazards [6,7,10,11] i.c. the approximately 2-fold higher tobacco and alcohol consumption by Surinamese men when compared to women [16-18]. Obviously, these assumptions must be confirmed in more comprehensive studies. The almost 6-fold higher incidence of laryngeal cancer in men than in women is greater than that for any other site [5], and is consistent with reports mentioning that larynx cancer is predominantly a cancer of men [5].

The marked age-dependent increase in incidence rates of overall head and neck cancers is in conformity with the general consensus of malignancy progressing in a multi-step fashion and over many years, eventually manifesting in older individuals [31]. Thus, chronic exposure of the upper aerodigestive tract to carcinogenic assaults may lead to critical DNA damage that may promote the development of premalignant lesions which can progress through hyperplasia, dysplasia, and in situ carcinoma to invasive malignant lesions [31]. The relatively high number of laryngeal and oral cancers in patients aged 50 years and older when compared to those younger than 50 years is consistent with this supposition as well as with studies mentioning that these neoplasms generally appear at age 60 years and above [5,27-29]. The occurrence of almost as many cases of nasopharyngeal cancer before as after age 50 years is in line with the relatively high frequency of this malignancy in both younger and older individuals and its bimodal age distribution with peaks around age 20 and 50 years [32-34]. Thus far, there is no solid explanation for this phenomenon.

Another noteworthy aspect of head and neck cancer epidemiology in Suriname was the clear ethnic predilection of (some of) these cancer types. There were significantly more overall, as well as oral cavity and laryngeal cancer cases in Creole when compared to Hindustani and Javanese, and very few nasopharyngeal malignancies in Hindustani while this neoplasm was the dominant subtype in Javanese. The former observation is in line with the 2-fold higher incidence of head and neck cancers in Afro-Americans when compared to American citizens of other ethnic backgrounds [35], as well as with the 2- to 6-fold higher incidence of most cancers in Surinamese Creole than in Hindustani and Javanese [20,24,36]. The relatively high frequency of nasopharyngeal cancer in Javanese is consistent with the relatively high susceptibility of South-east Asians to this neoplasm [37,38] and the persistence of this elevated risk after migration to a low-incidence country [38]. So far, none of these observations have been satisfactorily explained.

Summarizing, the results from this study suggest that Suriname is a low-incidence country for head and neck cancers. These neoplasms were in general more common in males than in females, occurred much more frequently in persons older than 50 years of age than in younger individuals, and manifested more often in Creole than in Hindustani and Javanese. The main exception was nasopharyngeal cancer, which made almost as many victims before as after age 50 years and may have a predilection for Javanese rather than for the other ethnic groups.

These findings suggest that the various strata evaluated in this study (males and females; older and younger individuals; and Creole, Hindustani and Javanese) may differ from each other with respect to their susceptibility to head and neck cancers and by extension, with respect to their receptivity to relevant risk factors. Elucidation of the nature of these risk factors and their specific impact on tumorigenesis is likely to contribute to the establishment of successful preventive measures. This goal may be advanced by more detailed follow-up studies on head and cancer epidemiology in the culturally, religiously, and ethnically diverse environment of Suriname.

2587

References

- Forastiere AA (2000) Head and neck cancer: overview of recent developments and future directions. Semin Oncol 27: 1-4.

- Fanucchi M, Khuri FR, Shin D, Johnstone PAS, Chen A (2006) Update in the management of head and neck cancer. Update on cancer therapeutics 1: 211-219.

- Haddad RI, Shin DM (2008) Recent advances in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 359: 1143-1154.

- Jones AS, Morar P, Phillips DE, Field JK, Husband D, et al. (1995) Second primary tumors in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 75: 1343-1353.

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55: 74-108.

- Andre K, Schraub S, Mercier M, Bontemps P (1995) Role of alcohol and tobacco in the aetiology of head and neck cancer: a case-control study in the Doubs region of France. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 31B: 301-309.

- Murata M, Takayama K, Choi BC, Pak AW (1996) A nested casecontrol study on alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking, and cancer. Cancer Detect Prev 20: 557-565.

- Jeng JH, Chang MC, Hahn LJ (2001) Role of areca nut in betel quid-associated chemical carcinogenesis: current awareness and future perspectives. Oral Oncol 37: 477-492.

- Taghavi N, Yazdi I (2007) Type of food and risk of oral cancer. Arch Iran Med 10: 227-232.

- Dietz A, Ramroth H, Urban T, Ahrens W, Becher H (2004) Exposure to cement dust, related occupational groups and laryngeal cancer risk: results of a population based case-control study. Int J Cancer 108: 907-911.

- Becher H, Ramroth H, Ahrens W, Risch A, Schmezer P, et al. (2005) Occupation, exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and laryngeal cancer risk. Int J Cancer 116: 451-457.

- D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, etal. (2007) Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 356: 1944-1956.

- Goldenberg D, Benoit NE, Begum S, Westra WH, Cohen Y, et al. (2004) Epstein-Barr virus in head and neck cancer assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Laryngoscope 114: 1027-1031.

- General Bureau of Statistics (2005) 7th General population and housing census in Suriname. Paramaribo, Suriname: ABS (General Bureau of Statistics/Census Office .

- Helman A (1977) Cultureel mozaïek van Suriname. Bijdrage tot onderling begrip. Zutphen, The Netherlands: De Walburg Pers.

- World Health Organization (2007) Suriname National Household Drug Prevalence Survey 2007.Global InfoBase: Data for saving lives - all data. World Health Organization.

- Pan American Health Organization (2004) Global youth tobacco survey Suriname. Paramaribo, Suriname: Ministry of Health.

- Monteiro MG (2007) Alcohol and public health in the Americas: a case for action. Washington, D.C., USA: PAHO.

- Rehm J, Room R, Graham K, Monteiro M, Gmel G, et al. (2003) The relationship of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking to burden of disease: an overview. Addiction 98: 1209-1228.

- Mans DR, Mohamedradja RN, Hoeblal AR, Rampadarath R, Joe SS, et al. (2003) Cancer incidence in Suriname from 1980 through 2000 a descriptive study. Tumori 89: 368-376.

- Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S (2005) Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 467-475.

- De Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, Madeleine MM, Franceschi S (2009) Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 124: 1626-1636.

- World Health Organization (2000) International classification of diseases for oncology. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Mans DR, Rijkaard E, Dollart J, Belgrave G, Tjin A Joe SS, et al. (2008) Differences between urban and rural areas of the Republic of Suriname in the ethnic and age distribution of cancer - A retrospective study from 1980 through 2004. The Open Epidemiology Journal 1: 30-35.

- Petersen PE (2009) Oral cancer prevention and control--the approach of the World Health Organization. Oral Oncol 45: 454- 460.

- American Cancer Society (2006) Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta, GA, USA: American Cancer Society.

- Andisheh-Tadbir A, Mehrabani D, Heydari ST (2008) Epidemiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity in Iran. J Craniofac Surg 19: 1699-1702.

- Sturgis EM, Wei Q, Spitz MR (2004) Descriptive epidemiology and risk factors for head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol 31: 726-733.

- Ho JH (1976) Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In: Hyrayama T, editor. Cancer in Asia. Baltimore, USA: Baltimore University Press, p. 49.

- Jaworowska E, Serrano-Fernandez P, Tarnowska C, Lubinski J, Kram A, et al. (2007) Clinical and epidemiological features of familial laryngeal cancer in Poland. Cancer Detect Prev 31: 270- 275.

- Forastiere A, Koch W, Trotti A, Sidransky D (2001) Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 345: 1890-1900.

- Cammoun M, Hoerner V, Mourali N (1974) Tumors of the nasopharynx in Tunisia. An anatomic and clinical study based on 143 cases. Cancer 33: 184-192.

- Balakrishnan U (1975) An additional younger-age peak for cancer of the nasopharynx. Int J Cancer 15: 651-657.

- Hirayama T, Ito Y (1981) A new view of the etiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Prev Med 10: 614-622.

- Gourin CG, Podolsky RH (2006) Racial disparities in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope 116: 1093-1106.

- Pan American Health Organization (1998) Suriname.In: Pan American Health Organization, editor. Health in the Americas. Washington D.C., USA: Pan American Health Organization, pp. 470-483.

- Kumar S, Mahanta J (1998) Aetiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A review. Indian J Cancer 35: 47-56.

- Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (2005) Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours.World Health Organization classification of tumors. Lyon, France : IARC Press.n n