Keywords

Music composers; Brain lesions; Cerebrovascular

Introduction

Few years ago, we published an article dedicated to the critical judgment of the artistic production by famous painters who suffered left or right focal cerebral lesion. We asked ourselves if the painters post lesional productions could be considered expression of unimpaired inventiveness and skill, or rather the expression of definite adjustments due to decreased of painting ability and creativity. We concluded that a hemispheric lesion significantly affects the painting production in all the investigated painters, who showed manifest modifications in their style [1,2].

In consequence of the above assumptions, a question raised: if other artists who express their creativity in different modality, i.e., in musical domain, manifest a parallel impoverishment in the quality of their artistic production. This investigation and the correlated observations didn't appear predictable, due to the fact that in previous literature the opinions of different Authors are dissimilar and in some way contrasting, although, in general, they seem to justify style modifications as due to “simplification”, or, even, to “innovation”, “austere”,” enigmatic”, “ascetic”, with more “creative energy”, etc. [3].

In neuropsychological literature the troubles of musical competence, over all, are described after vascular cerebral lesion, and very frequently are referred to musicians affected by aphasia [4-6]. But musicians with decrease abilities in one or more musical subcomponents without aphasia [5,7-9], or vice versa musicians affected by aphasia without decrease of musical competences, are also described [10-14]. Definitely, the relationship between amusia and aphasia is not more considered required [15].

The reports regarding the musicians mentioned in literature, those who manifested deterioration of their musical competence as a consequence of cerebral progressive degenerative disease are very uncommon. Besides Alajouanine [16], who describe Maurice Ravel illness, we have very few other cases: NS [12] and MM [14] are not identified in other ways. NS and MM manifest a cerebral degeneration more evident on the left hemisphere associated with language deficits. However, apparently, they show preservation of musical competences: music recognition, lecture and writing of the scores, instrumental execution and direction. NS was not a composer, but MM was. Anyway, the ability to compose music was not specifically analyzed in both the cases.

Finally, as the preserving or deterioration of the composition competence after cerebral lesion, vascular or degenerative, the composers described in the previous literature are rare [11,13,16-20].

Concerning the composition ability after cerebral lesion, inferable by the previous literature, we could find some interesting suggestion regarding the relationship between stroke, music and creative output. In his very comprehensive and stimulating paper, Zagvazdin [3] affirms that Alfred Schnittke recovered and continued his creative work with “inspiring success”; after the stroke he wrote music of “exceptional lyrical generosity, even of embarrassing kitschiness, more austere style, enigmatic and ascetic, style simplification did not lead to a reduction in emotionality”. Ira Randall Thompson’s post-stroke compositions have been well received: independent critics consider them to be as good as his pre-stroke compositions, but musically somewhat “more conservative”. Benjamin Britten post-stroke scores, which are relatively short, are considered to be “superb” and final works were considered “somberly colored”; “the composer renewed creativity reached its peak”; no “enfeeblement of his imaginative powers”. Jean Langlais: the music of his poststroke years was described as “tingled with retrospection and introspection final burst of creative energy”. Igor Stravinsky: after stroke in 1956, composed more works, his music continued to show “development and innovation adopting the serial composition (dodecaphonique) method”. Vissarion Shebalin, after having suffered his first stroke in 1953 was not deprived of “the ability to complete a number of masterpieces” and his best opera in 1957 was premiered at the Bolshoi Theatre.

In conclusion, the musicians with composition production quoted in previous literature are described with preservation of good quality of their music construction and creativity. However, the judgments expressed by the different Authors could appear in some way generic and/or subjective, without the specific application of a common music grammar and syntactic rules and without accomplishment of a valid comparison between pre-lesional and post-lesional music creation.

So, we suggest, as a useful progress in a correct direction of a less generic and more objective judgment of composers who suffered cerebral lesion, a critical revision of pre-lesional versus post-lesional musical production. The proposed questions are the following: a) According to the judgment of competent musicians applying general official/academic rules, what kind of judgments could be expressed comparing the pre-lesional with the post-lesional creation of each composer? b) As for artistic creativity is it possible to draw a parallelism between post-lesional artistic production of paintings and the music compositions of composers suffering a cerebral lesion? c) Finally, music composers suffering unilateral cerebral lesion could use different cerebral areas or different expressive repertories permitting him to overcome the cerebro-lesional consequences?

Methodology

To answer these questions, we analyze the evolution of composition ability after cerebral lesion, as said above, of five composers: Maurice Ravel, Benjamin Britten, Alfred Schnittke and Vissarion Shebalin and Franco Donatoni an Italian composer. All of them suffered a cerebrovascular lesion at the left hemisphere, except Ravel who did manifest a degenerative cerebral pathology, but also in this case charged at the left hemisphere. No composers with right cerebral lesion/ pathology are actually mentioned in the literature.

As said above, we decide to analyze some masterpieces of music composers comparing the pre-lesional versus the postlesional music production, using as reference the general musical rules drawn by Arnold Schoenberg in his volume “Fundamentals of Musical Composition” [21]. This methodology includes a list of objective criteria to organize a comparative analysis of composers’ pieces: i.e., rhythm, timbre, melody, phrase, motif, form, motif-form connection and theme construction, harmonic complexity, counterpoint complexity, timbre complexity and orchestration. The composers studied with this methodology are Ravel, Schnittke, Britten and Shebalin. Donatoni, who created very modern masterpieces, requires a different critical approach, according to the peculiar characteristics of his production.

To define more objectively the modifications of compositional production of the above musicians, we involve in the critical judgment four experts in music composition: Fabrizio Fanticini, composition teacher at the Parma’s Conservatory (Ravel, Schnittke, Shebalin, Donatoni); Maria Grazia Bellocchio, piano’s teacher at the Bergamo’s conservatory and concert performer (Ravel, Donatoni); Franco Petracchi, double bass’s virtuoso and teacher at the Géneve’s Conservatory and Cremona’s master, concert performer and orchestra’s conductor (Ravel, Donatoni); Daniela Petracchi, cello’s teacher at the Terni’s Conservatory and concert performer (Britten, Schnittke); Maria Isabella De Carli piano’s teacher at the Milan’s conservatory and concert performer (Donatoni); Maurizio Longoni, clarinets’ teacher at the Milan’s Scuola Civica and concert performer (Donatoni).

Composers who suffered degenerative cerebral pathology

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) history and disease: Ravel is considered one of the most important “orchestrators” of all history of music and also one of the most important composers for his peculiar capacity of “timbre construction”. He was interested in exotic music (i.e., Sherazade), but also in Spanish music (Rhapsody Española and Bolero). He has been influenced by Igor Stravinsky and by Russian Ballets: that resulted in a return to neoclassic style. Ravel travelled considerably also as a conductor. During his visit in the United States he was exposed also to American jazz and to elements of blues style which he included in his later pieces.

In 1927 Maurice Ravel began to manifest the first difficulties playing the piano, reading a score and in speech. During the period 1928-1931 he manifested a slow but evident symptoms’ progression, which evolved in aphasia, agraphia, alexia and apraxia. In 1932 he had a taxi accident with facial and cranial traumatism described as “mild-moderate”, followed by rapid exacerbation of musical, speech, praxical and memory disabilities, walking impairment and insomnia. That rapid negative evolution of cognitive and physical dysfunctions could be interpreted as an “anticipatory effect” induced by the cranial-facial traumatism. During the period 1932-1936 he progressively manifested a complete musical alexia and agraphia with a lot of errors even in coping music. He was unable to sol-fa and to play the piano while reading written notes. At the end of that period he was completely unable to play the piano and to conduct an orchestra. In composing he said “the music swirl in my mind, but I am no more able to fix it on the paper”. In 1937 Ravel was completely unable to speak and to recognize music. This led to an exploratory surgery, supposing a hydrocephalus or a brain tumor, but no other evidence of cerebral damage was discovered than shrinkage of the brain. After three days Ravel died.

Connection between Ravel composition ability and his illness: In the scientific literature, the hypothesis put forward the interpretation of apparent coexistence of preserved ability to compose music and the inability to play piano, to read and write music and to conduct, are different and not completely comparable. For example, Baeck [22] affirmed that Ravel was possibly afflicted by a progressive neurological illness that destroyed his artistic production while preserving his musical sensibility and aesthetic judgment. For Warren [23] Ravel composed the Bolero as a study of crescendo and orchestration, without the intension of creating music; for him the two piano concertos, completed after Bolero, are both masterpieces of the genre. He added that the slow movement of the Concerto in sol is graced by a melody of Mozartian delicacy. In Warren’s opinion, Ravel's “timbre mastery is undisputed, but he was also a melodist of rare invention, and there is little evidence that this gift deserted him even though he was tragically deprived of the means to realize his ideas”. Amaducci et al., [15] affirm that Bolero is sufficiently different from other compositions to raise the question that perhaps the balance between Ravel’s two hemispheres was being modified. The G-major piano concerto is in part an elaboration of sketches composed earlier. Concerto for Left Hand consists of movement with a number of contrasting episodes in which “themes and phases are shorter and less elaborate”…” orchestration uses a greater number of timbres deriving from the orchestra” “has a striking irregular pulsating style” is music “originate predominantly from the right hemisphere”.

Tudor and co-workers [24] affirmed that the Bolero and the Concerto for Left Hand were the last of Ravel's works (the onset of his disease), so it is possible that he projected the influence of the healthy right hemisphere into his music (and on creative process) because his left hemisphere was damaged. Indeed, in these last music works one can feel the predominance of changes in pitch (timbre) (elaborate by the right hemisphere), in comparison to only few changes of melody (elaborate by the left hemisphere).

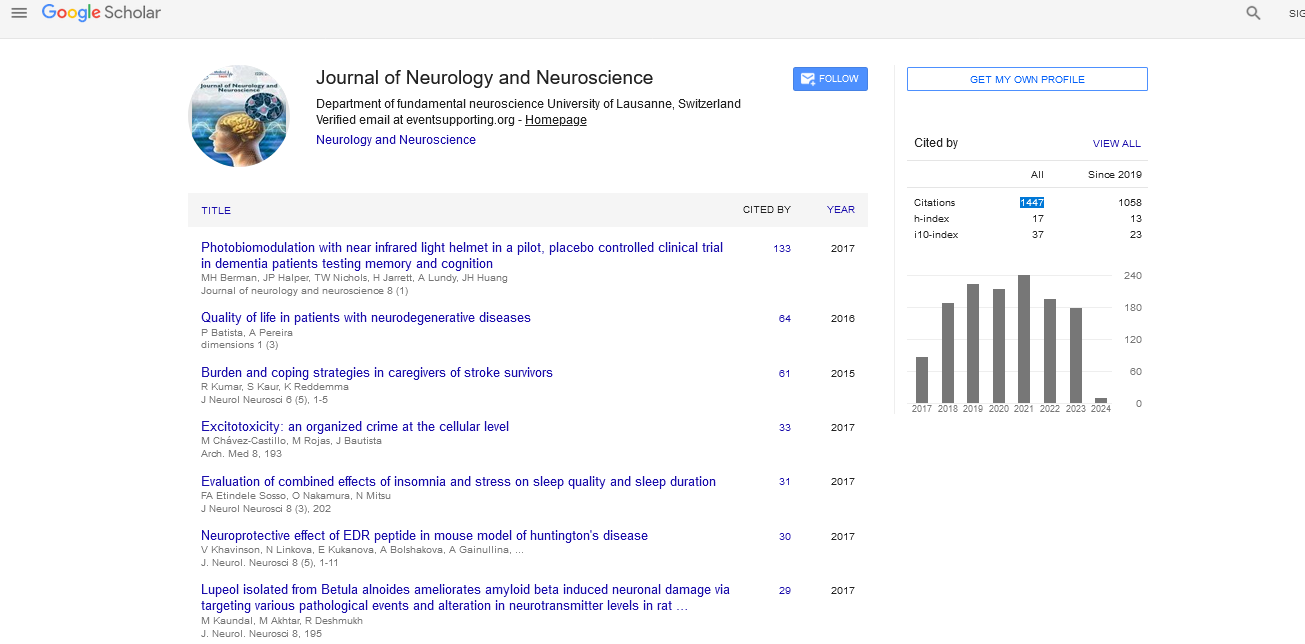

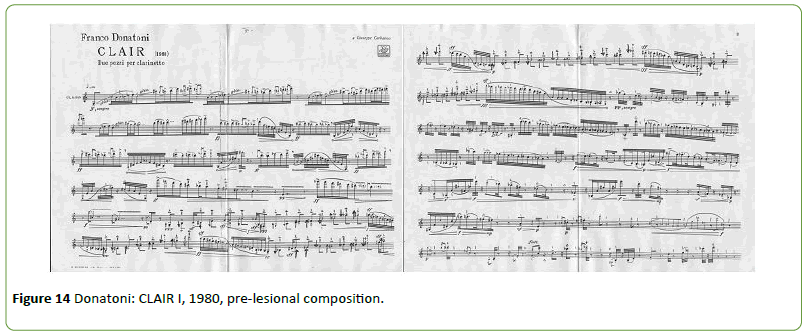

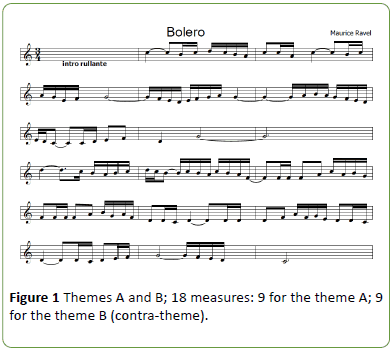

Our analysis and interpretation: Bolero, 1928: This masterpiece was commissioned by Ida Rubinstein, the Russian dancer, as Ballet music. It represents a variation set based on orchestration. It is composed only by two themes, A-B (Figure 1), a constant rhythm and by one phrase/period of 18 measures (usually the measures are 16) for each of the two themes. They in turn, don't develop but are repeated many times (170 times), potentially endlessly. The only changes are the orchestration and the colors given.

Figure 1: Themes A and B; 18 measures: 9 for the theme A; 9 for the theme B (contra-theme).

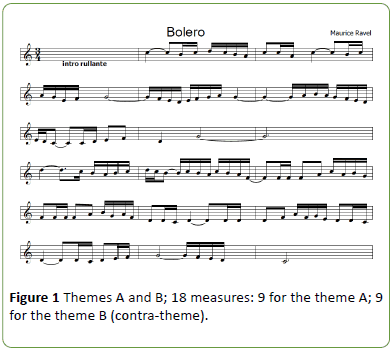

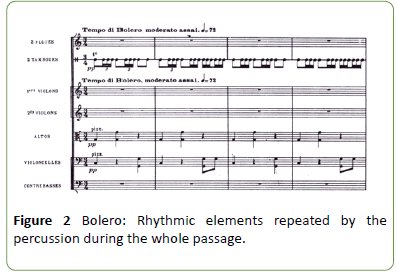

Bolero it is only on do major until the end (absence of tonal evolution, absence of harmony), except for the final section when a modulation on Mi major appears, and in that sorts out of the monotony and permits the passage conclusion (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Bolero: Rhythmic elements repeated by the percussion during the whole passage.

The melody is very simple, continuously the same. The rhythm it is given by the drum, constantly the same, inside a rigorous construction. The rhythm and the melody are juxtaposed, but remain separated and they never interact one into the other. The timbre is at master’s level, the sonority is excellent.

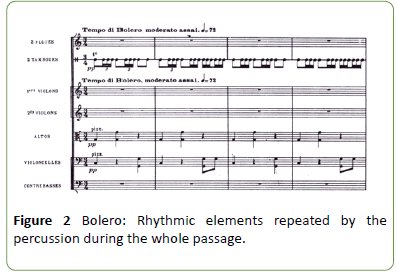

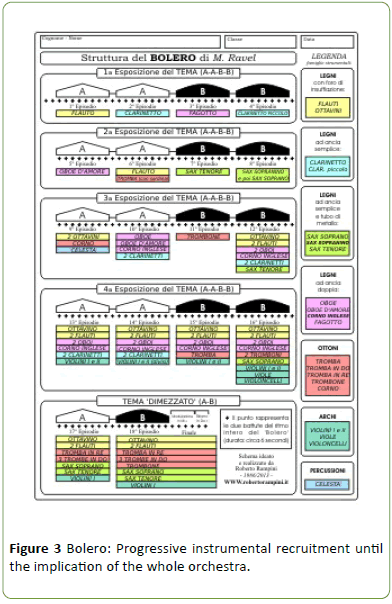

It is constituted by a great “crescendo”, with dynamic progressive phonic intensification (from “pianissimo” to “fortissimo”) with progressive instrumental recruitment.

The Form is circular, almost “mathematical” (Ravel was very interested in mechanical rules). Bolero it considered revolutionary because the composer shifts the attention on the orchestration developing a melody of timbres (klangfarbenmelodie) with continuous variations. He produces a timbre using the orchestra. Lenny Bernstein, himself composer and director, affirms that the Bolero is a perfect example of orchestration, even though it is one of the most obvious musical passages in respect to the musical form. It is without form; it is without architecture (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Bolero: Progressive instrumental recruitment until the implication of the whole orchestra.

In Enzo Restagno’s words: “the physiology of Bolero consists in a incessantly repeated tentative to match the melody with the regular scan of time… ”; ” the theme and the contra-theme of Bolero cannot get out of tonal framework which it stands as a insurmountable border”…. “The paradox of this very popular masterpiece it is that is appreciated more and more as a enjoyable exemplary of entertainment” [25]. Ravel himself in an interview to the Daily Telegraph in 1931, affirmed: “the piece composed by myself consists entirely in a orchestral weaving without music trough a long very gradual crescendo” …. “an experiment in a very particular and limited direction” … “a masterpiece without music!” [25]. Lèvi-Strauss [26], on the other hand, talks of a musical “regression to a primitive cultural horizon”.

Bolero conclusions: Bolero represents one moment of the most eminent quality of music creativity in general, in particular of Ravel’s music. With Bolero, Ravel seems an anticipator of American musical movements, which will be followed, for example, by Minimalism. If Bolero is in a way influenced by the Author disease, the solutions appear genial.

Concerto in Sol for Piano (1928-1931): This Concerto is considered a musical track confused, with a form not very clear and with a low musical intensity. It is created with a sequence of three movements “allegro, adagio, assai-presto”. The first movement is composed looking on Mozart and Saint- Saens; the second movement is inspired by a chanson (Lied tripartite); the third movement by jazz, by black music, and also by music of a brass band. We found included many quotations and influences of previous experiences. Ravel throw in this piece everything without a rigorous selection, discovering, in spite of this, equilibrium of composition.

The Mozart reference is justified by many musical ideas, main and minor, alternated with virtuosity and a Ravelian mannerism. Generally, the orchestra and the piano play together; but not in his concerto en Sol: in this way the author reduces the difficulties of the composition. Ravel affirmed to Marguerite Long (pianist) that he wrote this piece “painfully”. The musicians don't love this concerto; the pianists avoid executing it. It is considered “an orchestral tissue without music”.

Concerto for piano for the Left hand (1928-1931): It is considered a masterpiece: a complex process into a technically complex synthesis. It represents a unique movement, in which two contrasting parts exist: the first, more dramatic and conventional; the second, more jazz oriented, in a continue overlapping. The debut is a no-debut, with an indefinite sound of low frequencies. It is created with a sequence of three tempos “lento-veloce-lento” (formally an unusual choice). This concerto is a collage, a succession of formal sections expressively constant, in which Ravel utilized serious music records.

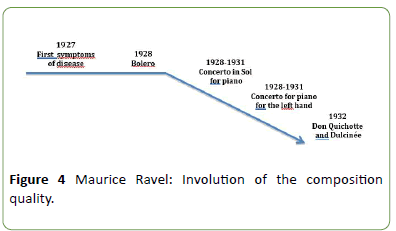

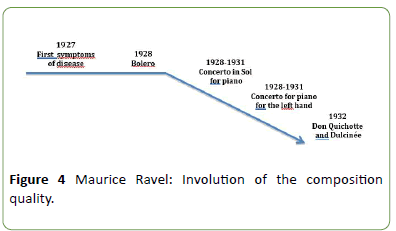

Don Quichotte and Dulcinée (1932): This opera it is considered dramatically simple. It is organized using only superimposed chords. It includes three very pleasant songs (Romanesque, Epique, A Boire) founded on three different dance rhythms with reference to the hispanic-arabic music. But graphically there is nothing there: the score is bare. Ravel imitates a popular manner to construct the music using minimal instruments. Is it genial that Ravel chooses this test that is corresponding to his residual composition abilities? A suspicion lingers among Ravel’s admirers: did he write it or “a friendly hand” did it? Since differences in writing may be noted between the score of Don Quichotte à Dulcinée and Ravel’s previous works [27] (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Maurice Ravel: Involution of the composition quality.

Ravel: general conclusions: The composition’s academic rules (timbre, melody, rhythm and form) seem maintained. But the last compositions are simplified; the complexity of counterpoint and of voices supra-position is very impoverished. Ravel shows an evident “organizing exertion” (see interview on Daily Telegraph). He uses simplified structures (Bolero), or classical simple models or reminiscences, influences, citations of his previous knownexperiences. The composition though is sufficiently maintained, but Ravel gradually has at his disposal fewer instruments automatically exploitable. He plays on his musical experience and his composition academic knowledge.

Composers who suffered cerebrovascular lesions

The described musical composers in the previous literature are five: Benjamin Britten, Alfred Schnittke, Ira Randall Thompson, Jean Langlais and Vissarion Shebalin. In order to have the possibility to analyze directly the music written before and after the cerebral lesion, we were able to review directly the sheets of Benjamin Britten, and Alfred Schnittke. For Vissarion Shebalin we found the pre-lesional sheets production but of the post lesional period we discovered only some music recordings. Moreover, we can investigate the musical sheets of Franco Donatoni, an Italian modern composer victim of a cerebrovascular lesion, no previously described in literature. Below we report the observations assessed by our mentioned composition’s experts.

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976): Benjamin Britten was a very famous English composer, pianist and conductor. Critics unanimously consider him the most important English composer of the XXth century, cosmopolite and great admirer of Mahler, Berg and Stravinsky. Has won international fame for films scores, fanfares, chansons folk for voice and piano (Our Hunting Fathers; Serenade for Tenor), coral opera (Hymn to S. Cecilia) but also opera music (Peter Grimes) and suites for cello. One of these best productions is the War Requiem, defined by musical critics “melodious and not difficult”.

In 1966 he suffered a left hemisphere cerebrovascular lesion. After that, he was able to compose “Death in Venice” in 1973, “Simple symphony” and two suites for cello (Op. 80 and Op. 87) and also the dramatic song Phaedra in 1976. The productions composed in the last decade of his life, are in general considered increasingly “more rarefied and evanescent” [28].

Analysis and interpretation: Our music experts analyzed in comparison the Cello suite composed before the cerebral lesion (No. 1 Op. 72 in 1964) and the two cello suites composed after the cerebral lesion (No. 2, Op. 80 in 1967 and No. 3, Op. 87 in 1971). The cello suites were dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich, the cellist. In particular, our music experts confronted the three “Fuga” movements. These are their observations.

First suite op. 72 for cello (pre-lesional: November- December 1964) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Britten: Fuga, Cello Suite No. 1, Op. 72, 1964 (prelesional composition).

Six movements open and without solution of continuity, connected two by two as dance couples: Fugue/Lament, Serenade/March, Bordone/ Perpetual Motion. Offered to Mstislav Rostropovich as Noel gift in 1964. Inspired by the Suites of Bach executed by the Russian cellist.

All the three suites are clearly inspired by Bach. The First one is certainly inspired by the I Suite in Sol Major.

At the beginning this suite is in barocco style; however modern timbre effects, dodecaphonic techniques in imitation of guitar, percussions and trumpet, enrich path progressively. Influences: Japanese theatre No, music Española, Balinese, choral.

Instrumental techniques: Polyphonic effects, natural and artificial harmony, pinched, arc percussions. So, very rich in musical effects.

Fugue: Traditional form ABA with three thematic cells. In the development, Britten is fun and creates harmonious relations and intervals among rather original notes. The timbric effect uses the more typical aspects of cello, the legato between more cello strings, double strings with detached sounds to underline segments of the theme; a very linear composition full of ideas, constructed using traditional music with good variety of rhythm and harmonies. Definitively it is a classic composition. Britten utilizes his classical composition knowledge.

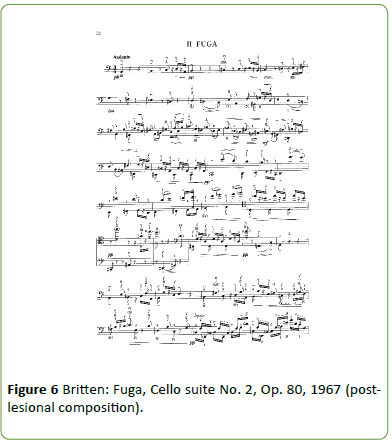

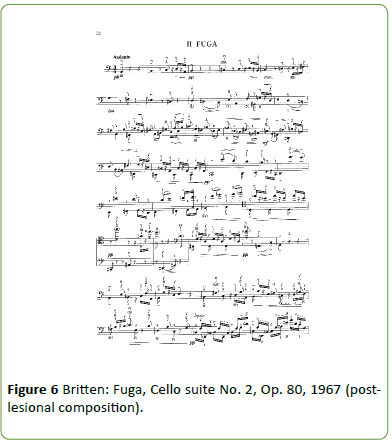

Second suite op. 80 for cello (post-lesional: August 1967) (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Britten: Fuga, Cello suite No. 2, Op. 80, 1967 (postlesional composition).

Five movements: Declamation, Fugue, Scherzo, Andante lento, Ciaccona. Britten transforms the segments of tonal motives to non-tonal explorations. The quarto’s interval at the beginning of the Declamato, guides and connects the construction of other movements. The compositional rigor contrasts with a ludic instinct that leads the composer to create new sound worlds and a new style intentionally ambiguous. This second suite is interesting on the experimental point of view. However, Britten cannot find an identity and an expressive intensity.

Fugue: Irregular, subject and contra-subject never meet; the pause is a part of the structure. Britten tries to abstract a traditional form, to break the composition into fragments that appear away and irregular; the counterpoint processes are less complexes, qualitatively less well-made, insufficiently polyphonic; Britten uses dodecaphonic music, with a more abstract structure, simplified, less melodic, with rhythms repetitive, less composed; the sounds are more disjoint, with leaps.

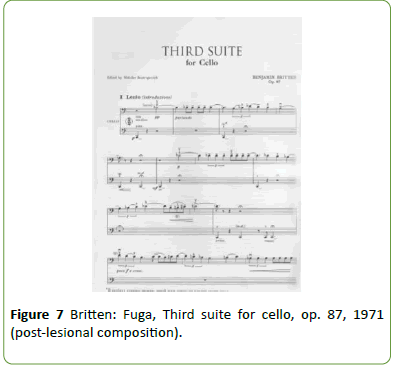

Third suite op. 87 for cello (post-lesional: February-March 1971) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Britten: Fuga, Third suite for cello, op. 87, 1971 (post-lesional composition).

This suite is a tribute to Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and to Russia. This composition is based on Russian popular themes and on the “Kontakion” in honor of the dead (hymn of the Orthodox Church). Musical references to two other famous composers, Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich, are also evident.

The Kontakion is the symbol of the cosmic circularity. The Passacaglia appears the darkest page written by Britten. In this composition (Barcarola) we find the quotation of the Prelude of the First Bach’s suite.

For the first time we find in Britten a such gloomy artistic composition. The do minor tonality is used by the author to evocate death. The tribute to Shostakovich induces Britten to complete the composition with a deep desolation without the words of hope and consolation that usually accompanies his finals.

The third suite appears musically the more interesting among the three suites. Shostakovich, Rostropovich, and the Russian music are the principal inspirations. The language of Britten seems to wish to regenerate. The Russian themes are enunciated and developed with a narrative conception.

Fugue: Britten tries to draw a different direction in respect to the previous compositions for cello. The technical difficulties, which in the First suite were above all instrumental, in this composition, require the capability to express emotional depth. Composed on Russian popular themes, elaborate by Ciaikovskij; introducing Russian reminiscences elaborated by Beethoven on Russian themes; music simplified, more linked to traditional harmonic forms, fragmented, with an alternation between songs themes and abstract themes. Britten regains, in simplified manner, less elaborated, the pre-lesional composition style, however using musical forms infantile (Barcarole); but Britten maintains his competence technique.

Our conclusion: In the Second Suite Britten tried to experiment, three years after the cerebral lesion, new techniques and goes forward on a less traditional music: the compositional result is positive from a technical and instrumental point of view, but not from a musical point of view. Britten knew very well the cello’s technical potentialities and demonstrates his capability to compensate possible underlying composition difficulties.

In the Third Suite, (composed seven years after the cerebral lesion) Britten seems to regain additionally the musical inspiration, even though, driven by a compositional material already existent (popular Russian music), the experimental component looks less relevant. In synthesis, Britten shows his ability to draw with a relative facility, after his cerebral lesion, to a technical pre-lesional expertise that supports him in the post-lesional composition.

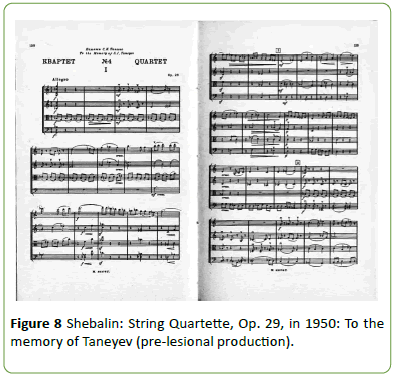

Vissarion Jakovlevic Shebalin (1902-1963): In 1928 he graduated from Moscow conservatory with the composer Miaskovskij and directed the same conservatory from 1942-1948. He spent his entire professional life in Moscow. In 1948, by resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, he was condemned (along with Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Miaskovskij and others) for “decadent formalism”, banished from the conservatory. He fell into obscurity afterwards. The censure was removed in May 1958, “restoring the dignity and integrity of Soviet composers.”Shostakovich acclaimed Shebalin as “the most talented educator” of Stalinist regime (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Shebalin: String Quartette, Op. 29, in 1950: To the memory of Taneyev (pre-lesional production).

Shebalin was a cultured and erudite composer; his style was intellectual and academic, but theoretical (Figures 8 and 9). He composed in many musical genres: operas, symphonies (i.e., Lenin), string quartets, trios, romances during 1929-1942 very loved in Russia, choral music, popular songs and film scores. He was defined “National Artist” by the Soviet Unit government because he was “conformed to the political suggestions and approved by the dominant thought”. He instrumentalised also the M.P. Mussorgsky’s opera “The Sorokin marketplace”.

Figure 9: Shebalin: Romance voice and piano, on poetry of Alexander Pushkin, Op. 23, 1935 (pre-lesional composition).

In September 1953, aged 51, after some years of severe hypertension, he suffered a first stroke with right face paresis, slight sensitive disturbance at the right hand and severe disturbance of speech. This stroke was followed after some months by “complete recovery” [17] and he was able to return to his work. In that period of remission, he continued to work with his students writing with his left hand. A second stroke came in 1959, more severe and with transitory loss of consciousness. It impaired completely his language capabilities (global aphasia) and was associated with right spastic hemiparesis. After six months he recovered leg movements and walking. His language expression and comprehension improved only partially. The description [17] of his aphasia profile is very accurate. In fact, he worked with a team of linguistics and neuropsychologists because of his fluent knowledge of many languages before the strokes. In the last part of this paper, the Authors wrote: “while aphasic, he finished compositions which he had started to write before he was taken ill, and he created a series of new compositions which other musicians considered to be up to standard, and which did not significantly differ from the compositions of his earlier years…. He did not simply go back to older works and revise them, but he also created completely new and different works”. The first performance of The Taming of the Shrew was played in October 1955, with piano accompaniment, by the Soviet Opera troupe from the Central Hall of Artists in Moscow; unhappy with the final scene Shebalin completely rewrote the ending of this opera for the work's first staging at the Bolshoi Theatre in August, 1957.

From 1959 to 1963, as detailed in the final part of the paper of Luria and co-workers [17], Shebalin composed: Op. 51 during 1959-1960: Sonatas for violin, viola and cello; Op. 52: Three Moldavian choruses during 1960-1962; Op. 55 in 1961: The Land of Mordovia; Op. 57 in 1963: To my Grandchildren; Op. 59 in 1963: In the Middle of the Forest and some choral works. He also revised and re-wrote other pieces (i.e., Sun on the Steppe, Op. 27) and the Quartets no. 8 and no. 9. In 1960 Shebalin took up his Symphony n. 4 again. Between 1962-1963 he completed, dedicated to Myaskovsky's memoryhis Fifth Symphony, described by Shostakovich as “a brilliant creative work, filled with highest emotions, optimistic and full life”. Shebalin, after these strokes completed musical pieces that he had begun before his illness and created a series of new works, “apparently without any decline of musical standards” [29] showing a “…remarkable preservation of receptive and expressive aspects of music, despite a profound aphasia” demonstrating “…probable correlation of the sparing of these abilities, with a talent developed early in childhood and a repetitive and formal training” [30]. In 1963 he suffered a third stroke in consequence of which he died.

Shebalin: Analysis and interpretation: It was no possible to find pieces concerning the post-lesional compositional production, but only concert recordings. We analyze some concert recordings, Fifth Symphony in 1962 and Quartet n. 9 in 1963 and we consider also the conclusions of the research made by the cellist Meta Weiss in Moscow, studying above all the changes in his compositional style after each stroke [31]. Her conclusions are, substantially that, following the strokes, Shebalin manifested a fragile physical state, was easily fatigued and limited to compose only few hours a day. “His musical style is markedly succinct”. The Weiss opinion is that Shebalin’s music changed in several ways post-stroke: “they are distinct differences in the structure of the themes, the imagery of music, and the tonality of his compositions.”

After the second stroke, Shebalin experimented with dodecaphonic style, though still within the tonal idiom, writing themes that featured all twelve tones melodically but relied on the functional harmony of tonality. All was mixed. His music (over all choruses) became very simple and “optimistic”, was very clean and straightforward, “but with new richness and depth despite the economy of means” [31].

His Fifth Symphony in 1962 appears to the contrary, in our judgment, a really intense and very different composition in respect to the other post-lesional production, but also in respect to the pre-lesional compositions. A possible interpretation of this apparently positive evolution of the Fifth Symphony could be that Shebalin in time felt himself finally free from the ties of the “official music” imposed by the political context. He arrived to manifest himself bringing out his real compositional personality, completing and publishing a previously conceived masterpiece.

The Quartet n. 9 Op. 58 in 1963: This composition manifests, with respect to previous Quartets composed during pre-lesional period (i.e., Quartet n. 5), an evident simplification on the counterpoint plan. Shebalin uses an “accompanied melody reducing the complexity of counterpoint”. This music is not more celebrative, but the composer is not able to get rid of technical forms of previous experience.

Alfred Schnittke, 1934-1998: He was a Russian very prolific and very academic composer: 9 symphonies; 6 large concerts; several concertos for quartet, violin, viola and piano, 60 musical scores [32]. He studied, initially, in Vienna and subsequently at the Moscow conservatory in 1961 where he graduated in composition. In the following years during 1962-1972, he became composition’s teacher. At the beginning his music was influenced by Dmitri Shostakovich; subsequently by Luigi Nono’s “serial technic”. He is described as “a man whose musical output is inextricably linked to the structures of life in the former Soviet Union”. For most of his adult life in Russia “Schnittke's music was powerfully shaped by the frustrations of the Soviet period and he reacted strongly against the ideology of the era [33]. His first epic symphony during 1969-1972 was banned by the Composers Union and in 1980 he was forbidden to leave the country. Schnittke is described as a composer full of contrasts. His composition is assimilable to many styles (from Chretien’s antique songs to the musical matter of twentieth century) “where the new doesn't develop”. His style was defined “polistylisme” for his tendency to juxtapose music of different styles, traditional and contemporary, in strict proximity. For him music was religious expression, and for that is slow and ritual. His symphonies lie arguably at the end of the Germanic symphonic tradition, yet each represents a new concept of the genre for the twentieth century. His works reveal the influence of Shostakovich among others, but remain strongly original. Each of his compositions can be understood primarily to offer a unique synthesis of many different influences and stylesThe most production is characterized by music for films and documentaries (about 70) in which the style is more uniform (i.e., Glass Accordion). His more famous productions are represented by the First Concerto Grosso in 1977; the second and third Strings Quartets during 1980-1983; the Strings Trio in 1985, the Cantata di Faust in 1983, the concerts for viola and cello during 1985-1986, Peer Gynt ballet during 1985-1987; the concert for viola and orchestra in 1986.

The spiritual dimension represents a fundamental theme in the Schnittke’s inspiration: i.e., the Requiem in 1975and the Quintet with piano during 1972-1976, both composed for his mother death. The Second Symphony, Sankt Florian, is subtitled Missa invisibilis, in the Fourth Symphony in 1984, represents liturgical traditions synthesis of different religious confessions, including elements from Psalmodies, Lutheran chorus, Gregorian tradition and Synagogue songs. From 1975 his music began to be played at all important contemporary music festivals, and in 1980 it was included in the concert programs of leading orchestras throughout the world. Schnittke was professor of composition at the Hamburg Musikhochschule from 1989 to 1994, was an honorary fellow of the Royal Academy of Music in London, and a member of the Free Academy of Arts in Hamburg.

Alfred Schnittke (The disease): In 1985 he manifested the first cerebral hemorrhage localized in the left hemisphere with transient coma state, right hemiplegia and aphasia, followed by referred “complete recovery”. In 1990 he moved to Hamburg. In 1991, Schnittke suffered a second hemorrhage episode, localized in the cerebellum. Also after that episode the recovery is described as complete. The Schnittke’s music lost his extroverted “polistylisme” and assumed a barer and withdrawn style; The Quartet in 1989 and the Sixth, Seventh and Eighth symphonies are a clear demonstration of that. In 1994, the composer manifests a third hemorrhage episode associate with right hemiplegia and aphasia “without amusia” and he stopped composing apart some brief pieces in 1997 and the ninth symphony in 1997, that remained incomplete. In 1998 the last hemorrhagic stroke is followed by his death [3].

These pre-lesional masterpieces (Figures 10 and 11) are characterized by “polistylisme” (combination of traditional styles and contemporaneous styles juxtapose in strict proximity).

Figure 10: Alfred Schnittke, 1966, Variations on a Chord (prelesional composition).

Figure 11: Schnittke: Third Streich Quartette, 1981, (prelesional composition).

Alfred Schnittke: Interpretation of post-lesional composition and conclusions: After the first cerebral hemorrhagic lesion, his personal style, defined “polistylisme” completely disappears and a musical style bare and shrink substitute it.

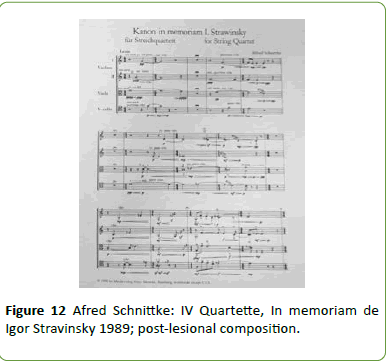

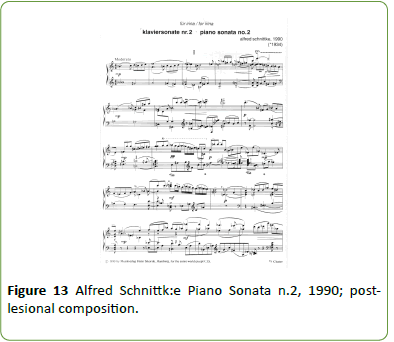

Analyzing the several music sheets of his compositional post-lesional production (i.e., the IV Quartet in 1989 in memory of Igor Stravinsky (Figure 12), the Sonata n. 2 in 1990 (Figure 13), characterized by elementary pianistic writing, and the Symphonies 6th in 1992, the 7th in 1993 and the 8th in 1994, we observed an evident decadence that manifest itself through an excessive simplification and many repetitions. He intensely “looks back” to his earlier compositional knowledge and production, and demonstrates to be proficient to maintain his consolidated technical competence.

Figure 12: Afred Schnittke: IV Quartette, In memoriam de Igor Stravinsky 1989; post-lesional composition.

Figure 13: Alfred Schnittk:e Piano Sonata n.2, 1990; postlesional composition.

Franco Donatoni (1927-2000): He learned how to play violin at the very early age; then composition at the Milan and Bologna conservatories and gained a specialization at the S. Cecilia Academy in Rome. He taught composition in many conservatories and Italian academies (i.e., Siena Academia) becoming internationally famous and composed very large number and different types of masterpieces. His musical production is always characterized by fast, skillful and difficult to execute musical pieces, composed for different instruments and camera groups (i.e., François Variations and Rima, for piano; Omar, for percussions; Lem, for double bass; Arpeggios, etc.). His production is characterized by different periods: he used musical process similar to logic-mathematical process, quite similar to codes, with expressive multiplicity (in the Fifties), creativity desacralisation (in the Sixties), transitions (in the Seventies), and in the Eighties, innovations. Famous soloists and conductors have executed his compositions [34].

The disease: Since his early age he manifested periodical and frequent episodes of depression; in the Eighties an important diabetic form, never treated, was diagnosed. In 1998 he suffered a left hemispheric stroke with secondary mild right hemiparesis and mild expressive language deficit. Subsequently he had to be helped by his pupils to compose the last pieces. The post-lesional production includes some compositions (Prom, ESA, In cauda V, Claire 2), which are characterized by collages of his previous production. In 2000 he died for a fatal second cerebral stroke.

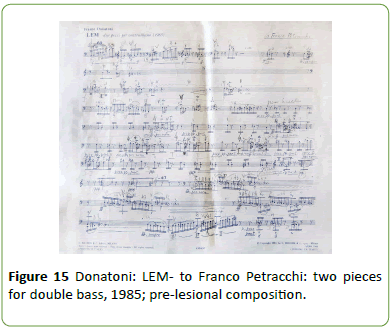

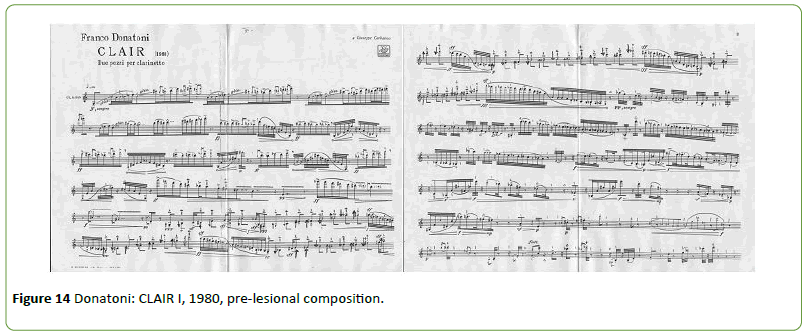

CLAIR I: 1980 (pre-lesional composition): The composition is irregular, with a large and complex variety of sequences of modules (Figure 14). Donatoni used only scales and trills or scales points and scales. His style remembers a compositional idea “in panels” (different compositional techniques “juxtaposed”). His originality and geniality is based on the capacity to compose pieces for an instrument (cello, clarinet, and double bass) identifying the “sound of the instrument”; for example composing the piece for clarinet he didn't use the “grave” register.

Figure 14: Donatoni: CLAIR I, 1980, pre-lesional composition.

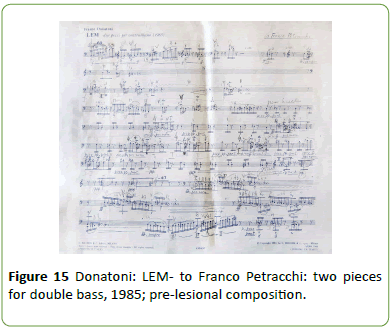

In the following years Donatoni composed other masterpieces; among them, from 1983-1985, LEM: two pieces for double bass; ALA: a piece for cello and double bass; ALAMARI: piece for cello, double bass and piano. All these four masterpieces, however, correspond, basically, to CLAIR I (composed only for clarinet) adapted for other instruments. Definitely Donatoni used rhythmical and melodic elements already inserted in CLAIR I applying different writing codes (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Donatoni: LEM- to Franco Petracchi: two pieces for double bass, 1985; pre-lesional composition.

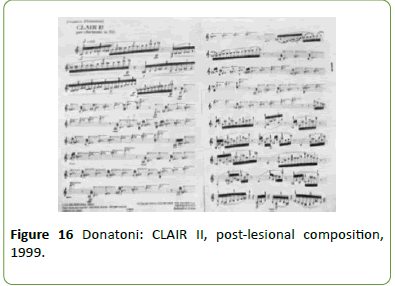

CLAIR II: 1999 (post-lesional composition): In this composition (Figure 16) Donatoni maintained his creative structure, though he became more schematic, more regular, more fixed. He utilized modules and sequences with very less variety, definitively less creative. In conclusion, he made a “rereading” of Claire I, simplifying parameters and rhythmic vivacity; he showed a partial difficulty to discover new modalities of revisiting the previous compositions and to transform the “simple material” in complex modality. However, the composer, as before, maintains an effective focalization to the instruments sound.

Figure 16: Donatoni: CLAIR II, post-lesional composition, 1999.

Franco Donatoni, interpretation and conclusions: Since 1980, when he suffered a serious diabetic form, his compositional material was frequently minimal and continuously modified (using proceedings of transmutation/ permutation) and a lot of repetitions. These observations are not new in our previous experience with painters suffering cerebral lesions. In the years immediately antecedent a cerebral lesion the quality of produced canvas is inferior in the majority of examined painters [1]. During 1995, Donatoni composed a tragic-comic orchestral opera “Alfred, Alfred”: in this work he even acted as a patient recovered in a hospital bed. After his first stroke in 1998, he made largely a revision of previous incomplete compositions, creating many collages. Furthermore, he exhibited the necessity to be aided by his pupils to compose the last pieces. He loss of his technical ability and the structural characters typical of his production and he showed a chromatic impoverishment of his compositional organization.

General conclusions and limits: Our principal question was: on the field of the artistic creativity can we draw a parallelism between the post-lesional production of paintings and the musical compositions of musicians suffering a cerebral lesion? Judging the quality of musical composition written by an expert composer, who manifests a cerebral pathology or suffers a cerebral lesion, in our opinion represents a real arduous task. Painted images could be only partially modified in the time and the canvas of a final painting is in front of us. Music, on the contrary, unfolds itself over time; the composition period is slower also in comparison to the musical thought, and it could be revised, readapted, modified many times before the conclusion.

As the applied methodology, the known musical culture [21] could be applied without difficulty to explore and judge the ancient and the contemporary musical styles. Conversely, is the classical musical culture appropriate to judge the style transformations of composers suffering cerebral lesion or affected by cerebral pathology? Moreover, in the 19th century music composition we find an expressive musical multiplicity that complicates the composition analysis. The cerebral processes that underlie the music compositional creation, up to this day are not sufficiently explored in the scientific literature, and they push us in the field of cultured suppositions. Many years ago J.A. Sloboda [35], in his chapter “Composition and Improvisation”, discussed largely the difficulty to explore the psychological inside the fundamental musical compositional processes. He considers unclear, unexplained and unexplored what compositional thought takes place when the composer structures, generates and writes his music. Sloboda summarizes his extensive and eloquent discussion suggesting a diagram of a “typical composer” processes (Figure 4) dividing the musical compositional procedure in “conscious” and “unconscious”. Lastly, in a section of the same chapter named “observations of composers at work” this Author attempts to generate a protocol of composition (choral) with the goal to define a possible methodological approach to compositional processes. However, his effort remains, until today, substantially isolated and not followed by more exhaustive methodological approaches to this complex field.

So, that being said, we pose the following question: could the composer use different cerebral areas or different expressive repertories permitting him to overcome the cerebro-lesional consequences? The evolution/involution of Ravel compositions seem to demonstrate the existence of this opportunity when the pathological process is slow. Ravel maintained in time the composition’s academic rules (timbre, melody, rhythm and form), showing gradually more simplified classical models and structures, even though referring to his academic knowledge and previous musical experience. However, when the pathological event is sudden, as in cerebrovascular lesions, the composer seems to exhibit a great variability and multiplicity of compensational possibilities to produce his music. This, despite the fact that all the described composers have suffered left hemisphere vascular lesions, ischemic or hemorrhagic, isolated or multiplied. The described composers definitely show different compositional modifications: an impoverishment of compositional organization (Donatoni); loss of technical process and of the structural musical characters (Donatoni); new simplified technique (Britten); a style modification with simplification and repetitions (Schnittke) or excessively “succinct” (Shebalin); differences in the structure of the themes and of the compositional tonality (Shebalin). Differences are observed also in the composer attempts to “compensate” their musical difficulties: creating collage of previous incomplete compositions (Donatoni); completing previously conceived masterpiece (Shebalin); or looking back to past compositional knowledge and production, referring to their consolidated technical competence (Schnittke, Shebalin, Britten); or showing the necessity to be aided to compose (Donatoni). Britten represents, compared with the other composers who suffered a cerebro vascular lesions, a partial exception because, after the first cerebrovascular episode, he experienced a ten years interval of moderately good health before the second and fatal cerebrovascular episode. During that period, he reached a progressive physical recuperation, a capability to compensate his compositional difficulties (his music was defined after the lesion “more rarefied and evanescent”) with suitable restoration of his musical inspiration and pre-lesional musical and technical expertise.

Conclusion

Today it seems to us still difficult to identify sure references to judge the musical compositions processes in general and, above all, the style modifications of music composition in presence of cerebral pathology. However, it seems also evident that the above examined composers employ, in their postlesional production and in respect to the pre-lesional production, simplified structures or simple classic models or reminiscences, influences, citations referred to their previous experience, related to harmonic traditional forms, less elaborates, frequently fragmented, static and repetitive. The compositional background character doesn’t change, and they maintain, in some way, their “poetry”, but the modality to apply it became more “technical”. The examined composers lose their organizational capacity, but they do not loose form and style. The more academicals composers demonstrated a general impoverished process associated with a loss of compositional vivacity (i.e., Schnittke). The composers who instead “play the new” (i.e., Donatoni), demonstrate, as said above, a vanished of their technical procedure, a loss of the structural characters representative of their production, a chromatic impoverishment of their compositional organization.

As neurologists and neuro-aesthetics’ lovers, we are persuaded that is necessary to define a structured methodology permitting a definition, an evaluation, a measure of modifications of the composition, a methodology as objective as possible, with the obligatory collaboration of musical composition specialists. The musical creativity, as the creativity in all the other fields, requires with elevated probability, an intact brain. The evaluation and the quality judgment of artistry modifications after cerebral lesion, or in presence of any cerebral pathology, requires a specific expert competence in each artistry field based on academic rules, historical evolution and deep musical knowledge, defining and applying. It is our profound opinion that is not appropriate to accept and formulate judgments about compositional creativity, pictorial, musical or of any other type, on the basis of “aesthetic impressions” or “aesthetic pleasure” or “personal sensitivity”. The neuro-aesthetics strongly claims defined methodology and solicits scientific procedures application.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for their professional cooperation to the critical reading and interpretation of masterpieces of the composers described in the paper also to:

Mr. Franco Petracchi, double-bass’s professor at the High School of the Genève’s Conservatory and at the Cremona Stauffer Foundation, soloist, concert performer and orchestra’s conductor (Donatoni).

Mr. Maria Isabella De Carli piano’s professor at the Milan’s Conservatory and concert performer (Donatoni).

Mr. Maurizio Longoni, clarinet’s professor at the Milan’s Civic School and concert performer, Donatoni’s pupil (Donatoni).

We are very grateful to Dante Matelli for paper critical and style revisions.

21436

References

- Mazzucchi A, Pesci G, Trento D (1994) Cervello e Pittura. Effetti delle lesioni cerebrali sul linguaggio pittorico. Fratelli Palombi Editore in Roma.

- Mazzucchi A, Boller F, Sinforiani E (2013) Focal cerebral lesions and painting abilities. Progr Brain Res 204: 71-98.

- Zagvazdin Y (2015) Stroke, music, and creative output: Alfred Schnittke and other composers. Progr Brain Res 216: In: Altenmuller E, Finger S, Boller F (eds) Music, neurology and neurosciences. Historical Connections and Perspectives 7: 149-165.

- Wertheim N, Botez M (1961) Receptive amusia: A clinical analysis. Brain 84:19-30.

- Brust JCM (1980) Music and language: Musical alexia and agraphia. Brain 103: 367-392.

- Hofman S, Klein C, Arlazoroff A (1993) Common hemisphericity of language and music in a musician: A case report. J Comm Disor 26: 73-82.

- Botez MI, Wertheim N (1959) Expressive aphasia and amusia following right frontal lesion in a right-handed man. Brain 82: 186-203.

- Confavreux C, Croisile B, Garassus P, Aimard G, Trillet M (1992) Progressive amusia and aprosody. Arch Neurol 49: 971-976.

- Assal G (1973) Aphasie de Wernicke sans amusie chez un pianist. Rev Neurol 129: 251-255.

- Judd T, Gardner H, Geschwind N (1983) Alexia without agraphia in a composer. Brain 106: 435-457.

- Basso A, Capitani E (1985) Spared musical abilities in a conductor with global aphasia and ideomotor apraxia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 48: 407-412.

- Signoret JL, Van Eeckout P, Poncet M, Castaigne P (1987) Aphasie sans amusie chez un organiste aveugle. Rev Neurol 143:172-181.

- Tzortis C, Goldblum MC, Dang M, Forette F, Boller F (2000) Absence of amusia and preserved naming of musical instruments in an aphasic composer. Cortex 36: 227-242.

- Amaducci L, Grassi E, Boller F (2002) Maurice ravel and right-hemisphere musical creativity: Influence of disease on his last musical works? Eur J Neurol 9: 75-82.

- Alajouanine T (1948) Aphasia and artistic realization. Brain 71:229-241.

- Luria AR, Tsvetkova LS, Futer DS (1965) Aphasia in a composer. J Neurol Sci 2: 288-292.

- Henson RA (1988) Maurice Ravel’s illness: A tragedy of lost creativity. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 296:1585-1588.

- Wintersgill P (1992) Composition and decomposition: The illness of some of the great composers. Br J Gen Pract 535-537.

- Sergent J (1993) Music, the brain and ravel. Trends Neurol Sci 16: 168-172.

- Shoenberg A (1985) Fundamentals of musical composition. Faber and Faber, London.

- Baeck E (2005) The terminal illness and the last compositions of Maurice Ravel. Neurological disorders in famous artists. Frontiers of Neurology and Neurosciences 19: 132-140.

- Tudor L, Sikirić P, Tudor KI, Cambi-Sapunar L, Radonić V, et al. (2008) Amusia and aphasia of Bolero's creator, influence of the right hemisphere on music. Acta Med Croatica 62: 309-316.

- Chalupt R, Gerar M (1956) Ravel au Miroir de ses Lettres. Paris: Laffont.

- Trimble MR (2007) The soul in the brain: The cerebral basis of language, art and belief. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Ruiz E, MontañeÃŒÂÂÂÃÂs P (2005) Music and the brain: Gershwin and Shebalin. In Neurological Disorders. Neurological disorders in famous artists. Frontiers of Neurology and Neurosciences 19: 172-178.

- Weiss M (2013) Is there a link between music and language? How loss of language affected the compositions of Vissarion Shebalin, The Tokyo Foundation, Tokyo.

- Sloboda JA (1985) Composition and improvisation. In the musical mind. The cognitive psychology of music. Oxford Science Publications, UK. pp: 102-150.