Commentary Article - (2023) Volume 0, Issue 0

The Safety of Promoting Fish Consumption in Pregnancy

Jean Golding* and

Caroline M. Taylor

Centre for Academic Child Health, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, England, UK

*Correspondence:

Jean Golding, Centre for Academic Child Health, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol,

Bristol, England,

UK,

Email:

Received: 15-Aug-2023, Manuscript No. IPJNN-23-14023;

Editor assigned: 17-Aug-2023, Pre QC No. IPJNN-23-14023;

Reviewed: 31-Aug-2023, QC No. IPJNN-23-14023;

Revised: 07-Sep-2023, Manuscript No. IPJNN-23-14023;

Published:

15-Sep-2023, DOI: 10.4172/2171-6625.23.S7.002

Description

Since the Minamata tragedy in 1956 in which there were

adverse neurodevelopmental consequences to the offspring of

pregnant mothers eating shellfish contaminated with very high

levels of mercury, toxicologists have been aware of the

possible harmful neurological effects of prenatal exposure to

mercury on the offspring [1]. Subsequently there were other

tragic exposures to high levels of mercury in pregnancy with

similar results. This raised anxiety in the general population

to avoid mercury from all sources and at all levels of

exposure. A publication on prenatal mercury exposure in the

Faroes focussed attention specifically on seafood. The

population of the Faroes was known to have high blood levels

of mercury largely due to their high consumption of pilot

whale [2]. Grandjean and colleagues studied 917 offspring of

women and compared their IQ and other neurocognitive test

levels with the concentration of mercury in their cord blood at

the time of delivery [3]. They showed that, in general, the

higher the mercury level the lower the cognitive ability of the

offspring.

The cumulative effect of these reports was to convey the

message that seafood contains high levels of mercury, and that

this may harm the brain of the unborn child. Scientists had

shown that the amount of mercury in fish varied with the

species, with those at the higher end of the food chain, such as

shark or swordfish, having higher levels [4]. Although there was

ample evidence to indicate that if the mother ate fish during

pregnancy the offspring would benefit policy-makers advised

pregnant women to eat fish during pregnancy but to avoid those

fish with likely high levels of mercury [5]. This resulted in

confusion such that women were often unsure as to which fish

to avoid, and many then avoided fish altogether [6,7].

The initial results from the Faroes resulted in a number of

studies being devised to look at the long-term consequences of

fish consumption and the relationship with mercury. The most

statistically powerful of these were those undertaken in the

Seychelles in the Indian Ocean, where the majority of the

population were fish-eaters, and in the Avon Longitudinal Study

of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) in the UK [8,9]. Both studies

showed benefits of fish consumption during pregnancy. No adverse associations were found between maternal mercury levels

and neurodevelopment in the Seychelles where the

majority of the population ate fish frequently [10]. Recent

analyses of the ALSPAC cohort study have demonstrated that

although mercury levels in women who did not eat fish were

associated with poorer neurocognitive outcomes, the mercury

levels among fish eating mothers were associated with

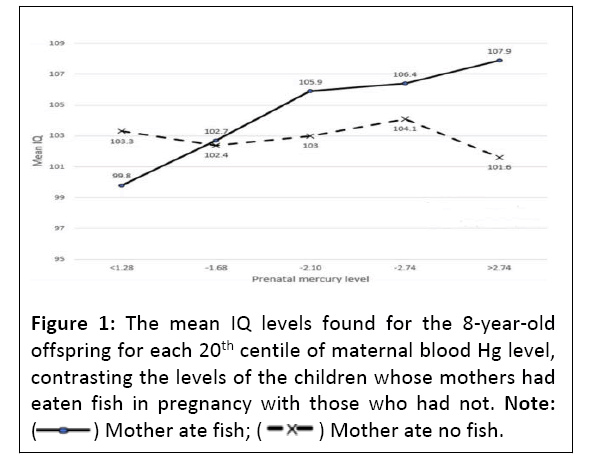

beneficial outcomes in their children in Figure 1, there

were significant interactions between fish consumption and

mercury blood level for eight further outcomes including IQ

and scores for educational achievements [11,12].

Figure 1: The mean IQ levels found for the 8-year-old

offspring for each 20th centile of maternal blood Hg level,

contrasting the levels of the children whose mothers had

eaten fish in pregnancy with those who had not. Note:

Conclusion

No studies have shown an adverse outcome with

consumption of fish that have high levels of mercury (consumers

of such fish would likely be within the higher end of maternal

blood mercury among fish-eaters which shows no deterioration

in offspring ability). Together with the Seychelles study, the

implication from the ALSPAC data is that it is better to

recommend fish consumption in pregnancy, regardless of

species. It should be noted that such a recommendation is not

for other seafood such as whale meat or shellfish where

contamination is likely to be much greater, and the nutritional

benefits of fish eating are not as great.

Funding Statement

CMT was funded by a Medical Research Council (MRC) Career

Development Award (grant number MR/T010010/1).

References

- Kondo K (2000) Congenital minamata disease: warnings from japan's experience. J Child Neurol 15:458-464.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Grandjean P, Weihe P, Jorgensen PJ, Clarkson T, Cernichiari E, et al. (1992) Impact of maternal seafood diet on fetal exposure to mercury, selenium, and lead. Arch Environ Health 47:185-195.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF, Debes F, Araki S, et al. (1997) Cognitive deficit in 7-year-old children with prenatal exposure to methylmercury. Neurotoxicol Teratol 19:417-428.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamps L R, Carr R, Miller H (1972) Total mercury-monomethylmercury content of several species of fish. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 8:273-279.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Hibbeln JR, Spiller P, Brenna JT, Golding J, Holub BJ, et al. (2019) Relationships between seafood consumption during pregnancy and childhood and neurocognitive development: Two systematic reviews. prostaglandins leukot essent fatty acids 151:14-36.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Oken E, Kleinman KP, Berland WE, Simon SR, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. (2003) Decline in fish consumption among pregnant women after a national mercury advisory. Obstet Gynecol 102:346-351.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Beasant L, Ingram I, Taylor CM (2023) Fish consumption in pregnancy in relation to national guidance in England in a mixed-methods study: The PEAR study. Nutrients 15:3217.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Myers GJ, Davidson PW, Cox C, Shamlaye CF, Palumbo D, et al. (2003) Prenatal methylmercury exposure from ocean fish consumption in the Seychelles child development study. Lancet. 361:1686-1692.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Hibbeln JR, Davis JM, Steer C, Emmett P, Rogers I, et al. (2007) Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): An observational cohort study. Lancet 369:578-585.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Davidson PW, Cory-Slechta DA, Thurston SW, Huang LS, Shamlaye CF, et al. (2011) Fish consumption and prenatal methylmercury exposure: cognitive and behavioral outcomes in the main cohort at 17 years from the Seychelles child development study. Neurotoxicology 32:711-717.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Golding J, Gregory S, Iles-Caven Y, Emond A, Hibbeln J, et al. (2017) Maternal prenatal blood mercury is not adversely associated with offspring IQ at 8 years provided the mother eats fish: A British prebirth cohort study. Int J Hyg Environ Health 220: 1161-1167.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Golding J, Taylor C, Iles-Caven Y, Gregory S (2022) The benefits of fish intake: Results concerning prenatal mercury exposure and child outcomes from the ALSPAC prebirth cohort. Neurotoxicology 91:22-30.

[Crossref] [Google scholar]

Citation: Golding J, Taylor CM (2023) The Safety of Promoting Fish Consumption in Pregnancy. J Neurol Neurosci Vol.14 No.S7:002