Mini Review Article - (2024) Volume 0, Issue 0

Timing of Lumbar ESIs: Do Pre-operative Epidural Injections Effect Lumbar Spine Surgery Outcomes

Kelly H Yoo,

Sina Sadeghzadeh,

Aaryan Shah and

Anand Veeravagu*

Department of Neurosurgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA

*Correspondence:

Anand Veeravagu, Department of Neurosurgery, Stanford University School of Medicine,

Stanford, California,

USA,

Email:

Received: 05-Dec-2023, Manuscript No. IPJNN-23-14341;

Editor assigned: 07-Dec-2023, Pre QC No. IPJNN-23-14341;

Reviewed: 21-Dec-2023, QC No. IPJNN-23-14341;

Revised: 28-Dec-2023, Manuscript No. IPJNN-23-14341;

Published:

04-Jan-2024, DOI: 10.4172/2171-6625.15.S9.001

Abstract

The management of lumbar spine disorders often require a multimodal approach,

with surgery considered for those unresponsive to conservative treatments.

Lumbar Epidural Steroid Injections (ESIs) are widely adopted for symptom

alleviation and functional enhancement. While preoperative lumbar ESIs are

proposed to enhance surgical outcomes, recent studies express concerns about

complications, particularly an elevated risk of Postoperative Infections (POIs) due

to corticosteroids.

The intricate link between preoperative lumbar ESIs and surgical outcomes has

been extensively explored. Retrospective analyses indicate a noticeable reduction

in preoperative pain scores post-ESIs, suggesting potential synergy with surgical

outcomes. The anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of ESIs may positively

impact the perioperative period, though apprehensions persist about associated

risks, including infection and delayed wound healing. Temporal considerations

are crucial, with studies indicating an augmented risk of POIs when ESIs are

administered within a month before lumbar spine surgeries. Moreover, elevated

intraoperative Dural Tear (DT) has been observed within three months of post-ESI,

attributed to steroid effects on local tissue, particularly collagen and fibroblasts.

DT risk is higher in elderly patients with reduced capacity for efficient return

to normal fibroblast function. Pragmatic clinical decision-making emphasizes

strategic surgery delay after ESI to mitigate risks. Individualized considerations

guided by shared decision-making become imperative for optimizing outcomes.

Further research is warranted, particularly through Randomized Controlled Trials

(RCTs), to elucidate and refine the intricate relationship between preoperative

lumbar ESIs and subsequent surgical outcomes. RCTs should encompass diverse

outcome measures, beyond preoperative pain scores, including function

improvement and complications. The implementation of standardized protocols

in RCTs will contribute to evidence-based guidelines and serve as foundational

pillars in optimizing patient care in lumbar spine surgery. In our review, we aim

to explore the temporal aspects of lumbar ESIs and their impact on outcomes in

lumbar spine surgery.

Keywords

Lumbar spine surgery; Epidural steroid injection; Quality outcomes

Introduction

The management of lumbar spine disorders often involves a

multimodal approach, with surgical measures considered a

viable option for patients exhibiting inadequate responses to

conservative treatments [1]. Lumbar Epidural Steroid Injections

(ESIs) have emerged as a widely adopted therapeutic modality,

demonstrating efficacy in alleviating symptoms and enhancing

functional status among patients with lumbar spine pathologies

[2,3]. These can be performed by a transforaminal, interlaminar, or caudal approach by injection of either a steroid alone or in

combination with a local anaesthetic agent [4].

Notably, the therapeutic potential of preoperative lumbar ESIs

in mitigating preoperative pain and inflammation prompted a

deeper exploration into their effects on subsequent surgical

interventions [5]. However, recent studies have proposed

apprehensions regarding potential complications, with a notable

focus on the elevated risk of Postoperative Infections (POIs) [5].

This concern is attributed to the immunosuppressive effects

of corticosteroids, potentiated by the prolonged half-life of

epidurally administered steroids [6,7]. Moreover, corticosteroids

exert a notable impact on local biochemistry, potentially inducing

alterations in tissue biology, including the development of hyper

vascularity and epidural scarring [8]. These changes may give

rise to a spectrum of challenges that are atypical in conventional

clinical scenarios.

Our review aims to explore the temporal aspects of lumbar ESIs,

analyzing the intricate interplay between their administration,

the surgical timeline, and the resulting outcomes [9,10]. We aim

to provide a comprehensive guide for clinicians and researchers

helping navigate the intricacies inherent in lumbar spine surgery.

Literature Review

The intricate interplay between preoperative lumbar ESIs and

surgical outcomes presents a multifaceted landscape in the realm

of spine surgery [11]. Numerous empirical studies have examined

the influence of preoperative ESIs on crucial dimensions such as pain relief, functional improvement, and the occurrence of

postoperative complications [12,13].

Recent retrospective analyses have revealed a significant

reduction in preoperative pain scores among patients undergoing

lumbar spine surgeries with preoperative ESIs [14,15]. This

observation prompted the hypothesis that adequate preoperative

pain management may substantially contribute to optimizing

surgical outcomes [16].

A paramount consideration lies in comprehending the potential

mechanisms underlying the impact of preoperative lumbar

ESIs on surgical outcomes. The intrinsic anti-inflammatory and

analgesic properties inherent in steroids administered through

ESIs hold promise for significantly reducing preoperative pain,

thereby exerting a positive influence on the perioperative period

[17]. Nevertheless, persistent concerns linger regarding potential

risks associated with corticosteroid use, spanning infection, Dural

Tear (DT), delayed wound healing, and other complications [18].

Temporal considerations play a crucial role in postoperative

outcomes and complications in various lumbar spine surgeries

procedures, including decompression [7,19-21], fusion [20,22- 24], or a combination of both [25,26] (Table 1). Studies consistently

highlight that preoperative ESIs administered within one month

preceding lumbar spine decompression or fusion correlate with

an augmented risk of POIs. This temporal phenomenon aligns

coherently with the well-established immunosuppressive effects

of steroids [27].

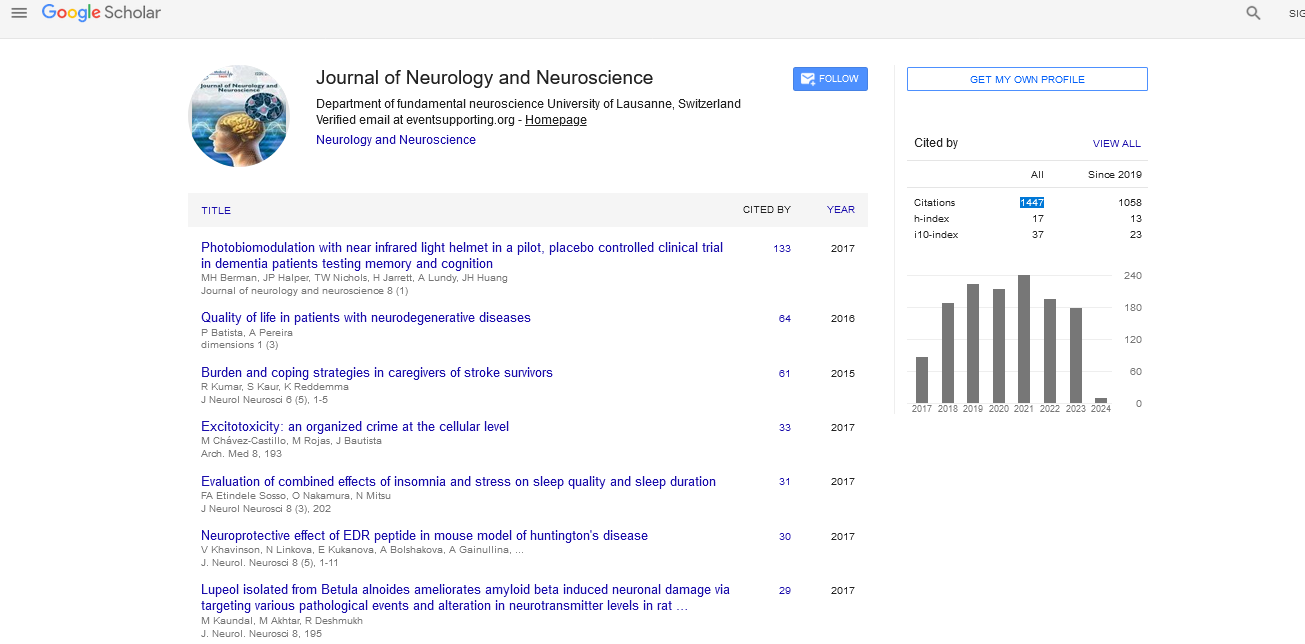

| Author (year) |

Study dates |

Surgical procedure |

Study design |

Infection |

ESI |

| Lumbar Spine Decompression |

| Yang et al. (2016) [7] |

2005-2012 |

Primary single-level lumbar decompression |

Proprietary Medicare claims database (PearlDriver) (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI (ICD-9, CPT) |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI** |

| Seavey et al. (2017) [21] |

2009-2014 |

Single-level lumbar decompression without instrumentation |

Military health system data repository searched (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI (ICD-9) |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI. 64% (539/847) received single ESI, 22% received 2, 9% received 3, and 4% received >3 ESI |

| Donnally et al. (2018) [19] |

2005-2014 |

Primary single-level lumbar decompression without instrumentation |

Proprietary Medicare claims database (PearlDriver) (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI (ICD-9, CPT) |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI** |

| Kreitz et al. (2020) [20] |

2000-2017 |

Lumbar decompression* |

Single academic orthopedic practice (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI (ICD-9) |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI** |

| Lumbar Spine Fusion |

| Singla et al. (2017) [24] |

2005-2012 |

Single or multilevel posterior lumbar spinal fusion |

Proprietary Medicare claims database (PearlDriver) (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI (ICD-9, CPT) |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI** |

| Pisano et al. (2020) [23] |

2009-2014 |

Single or multilevel lumbar spine fusion |

Military health system data repository (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI (ICD-9) |

Transforaminal and interlaminar ESI (348/612=0.57) Facet joint injections (264/612=0.43) |

| Kreitz et al. (2020) [20] |

2000-2017 |

Lumbar fusion* |

Single academic orthopedic practice (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI (ICD-9) |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI** |

| Li et al. (2020) [22] |

2015-2019 |

Instrumented posterior lumbar fusion* |

Prospective study, single institution |

6 months POI (prospectively) |

Transforaminal ESI** |

| Lumbar Spine Decompression and Fusion Combined |

| Hartveldt et al. (2016) [25] |

2005-2015 |

Single or multilevel decompression and fusion |

Retrospective study at 2 affiliated tertiary care referral centers (CPT, ICD-9) |

90 days POI requiring incision and drainage in OR |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI** |

| Koltsov et al. (2021) [26] |

2007-2015 |

Decompression, fusion, interbody fusion, discectomy |

Proprietary nationally representative database (MarketScan) (ICD-9, CPT) |

90 days POI (ICD-9, CPT) |

Transforaminal or interlaminar ESI** |

Note: POI: Postoperative Infection; ESI: Epidural Steroid Injection; OR: Operating Room; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; CPT: Current Procedural Terminology, *number of levels not specified ** number of subjects with multiple injections not reported.

Table 1: Characteristics of studies stratified by lumbar spine surgery procedure.

Moreover, a study by Shakya et al. revealed a noteworthy finding

that a preoperative lumbar ESI given within three months

of surgery significantly elevates the risk of an intraoperative

DT (p<0.05). Interestingly, occurrences of POIs and other

complications remained comparable regardless of the history of

ESIs [28].

In clinical scenarios where shared decision-making facilitates

optimal risk mitigation, adopting a strategy of delaying surgery for

one month post-ESI in younger adults and up to three months in

older adults emerges as a judicious and reasonable management

approach.

Discussion

The multifaceted exploration of the intricate relationship between

preoperative lumbar ESIs and surgical outcomes unveils a nuanced

landscape in the realm of spine neurosurgery [20]. Recent

retrospective analyses have elucidated a discernible reduction

in preoperative pain scores among patients undergoing ESIs,

suggesting a potential synergy between pain management and

favourable surgical outcomes [5]. A comprehensive understanding

of the underlying mechanisms is imperative, considering the anti-

inflammatory and analgesic properties of steroids administered

through ESIs, while concurrently acknowledging persistent

concerns related to associated risks [27,29].

Temporal considerations introduce an additional layer to this

relationship, with studies highlighting an increased risk of POIs

when preoperative ESIs are administered within a month of

lumbar spine surgeries [30]. Furthermore, an elevated incidence

of intraoperative DT has been observed when surgery was

performed within three months post-ESI [28]. This phenomenon

can be attributed to the direct effects of steroids on the local

tissue. Collagen, the most common structure in the extracellular

matrix of the meninges, undergoes alterations due to the

inhibitory effects of corticosteroids on fibroblasts, affecting their

intracytoplasmic mitochondria [31,32]. Dura injected with

corticosteroids exhibits a significantly decreased number of

intracytoplasmic mitochondria in dural fibroblasts, leading

to compromised function. This results in decreased collagen

production, eventually compromising the material proporties of

the dural tissue and making it susceptible to tear even with minor

injury [31]. The heightened occurrence of DT observed in patients administered steroids within three months of surgery can be

attributed to the peak steroid effects during this period [33]. The

effects gradually diminish over time as fibroblasts regain normal

functionality. Additionally, the risk of DT is more pronounced in

elderly patients, who may exhibit a reduced capacity for efficient

return to normal fibroblast function [34].

This temporal dimension advocates for a pragmatic approach

in clinical decision-making, emphasizing the potential benefit

of strategically delaying surgery after an ESI to mitigate risks.

The necessity for individualized considerations across diverse

patient populations, guided by shared decision-making, becomes

imperative in optimizing outcomes.

Looking ahead, the imperative for additional Randomized

Controlled Trials (RCTs) becomes evident, aiming to elucidate and

refine our comprehension of the intricate relationship between

preoperative lumbar ESIs and subsequent surgical outcomes

[35,36]. These trials should extend beyond the singular focus on

validation of the observed reduction in preoperative pain scores,

evolving into systematic investigations encompassing a diverse

range of outcome measures, including functional improvement

and complications. The implementation of standardized protocols

within these trials will not only contribute to the formulation of

evidence-based guidelines but will also serve as foundational

pillars in optimizing patient care with tailored approach for each

intervention within the dynamic landscape of lumbar spine

surgery [37].

Conclusion

Our review underscores the intricate relationship between

preoperative lumbar ESIs and surgical outcomes within the realm

of lumbar spine surgery. While acknowledging the potential

advantages of sufficient preoperative pain management and

functional enhancement, we emphasize the necessity for a

thorough evaluation of associated risks.

As empirical evidence unveiled a notable reduction in preoperative

pain scores following lumbar ESIs, our understanding of this

intervention was propelled beyond mere palliation, signalling

their potential to optimize surgical results. However, these

advancements are tempered by lingering concerns with increased

risk of POIs. The temporal dimension of this relationship introduces a pragmatic layer to clinical decision-making across

diverse patient populations.

This review advocates for a comprehensive and individualized

approach to optimized patient care, highlighting the critical need

for a nuanced strategy, further research endeavours through

RCTs, and a steadfast dedication to advancing the evidence base

in lumbar spine surgery.

References

- Fornari M, Robertson SC, Pereira P, Zileli M, Anania CD, et al. (2020) Conservative treatment and percutaneous pain relief techniques in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: wfns spine committee recommendations. World Neurosurg X 7:100079.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa H, Varshneya K, Stienen MN, Veeravagu A (2023) Do epidural steroid injections affect outcomes and costs in cervical degenerative disease? A retrospective marketscan database analysis. Global Spine J 13:1812-1820.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Carassiti M, Pascarella G, Strumia A, Russo F, Papalia GF, et al. (2021) Epidural steroid injections for low back pain: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Manchikanti L, Singh V, Pampati V, Falco FJ, Hirsch JA (2015) Comparison of the efficacy of caudal, interlaminar, and transforaminal epidural injections in managing lumbar disc herniation: is one method superior to the other? Korean J Pain 28:11-21.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Hooten WM, Eberhart ND, Cao F, Gerberi DJ, Moman RN, et al. (2023) Preoperative epidural steroid injections and postoperative infections after lumbar or cervical spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 7:349-365.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Cancienne JM, Werner BC, Puvanesarajah V, Hassanzadeh H, Singla A, et al. (2017) Does the timing of preoperative epidural steroid injection affect infection risk after acdf or posterior cervical fusion? Spine 42:71-77.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang S, Werner BC, Cancienne JM, Hassanzadeh H, Shimer AL, et al. (2016) Preoperative epidural injections are associated with increased risk of infection after single-level lumbar decompression. Spine J 16:191-196.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Meyer JS (1985) Biochemical effects of corticosteroids on neural tissues. Physiol Rev 65:946-1020.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Hooten WM, Nicholson WT, Gazelka HM, Reid JM, Moeschler SM, et al. (2016) Serum triamcinolone levels following interlaminar epidural injection. Reg Anesth Pain Med 41:75-79.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Lamer TJ, Dickson RR, Gazelka HM, Nicholson WT, Reid JM, et al. (2018) Serum triamcinolone levels following cervical interlaminar epidural injection. Pain Res Manag 2018:8474127.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kozak M, Hallan DR, Rizk E (2023) Epidural steroid injection prior to spinal surgery: a step-wise and wise approach. Cureus 15:e45125.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamble PC, Sharma A, Singh V, Natraj B, Devani D, et al. (2016) Outcome of single level disc prolapse treated with transforaminal steroid versus epidural steroid versus caudal steroids. Randomized Controlled Trial 25:217-221.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Riew KD, Yin Y, Gilula L, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. (2000) The effect of nerve-root injections on the need for operative treatment of lumbar radicular pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am 82:1589-1593.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Stewart JW, Dickson D, van Hal M, Aryeetey L, Sunna M, et al. (2023) Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane blocks for pain management after open lumbar laminectomy. Eur Spine J.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacob KC, Patel MR, Parsons AW, Vanjani NN, Pawlowski H, et al. (2021) The Effect of the severity of preoperative back pain on patient-reported outcomes, recovery ratios, and patient satisfaction following Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion (MIS-TLIF). World Neurosurg 156:e254-e265.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Tan M, Law LS-C, Gan TJ (2015) Optimizing pain management to facilitate enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. Can J Anaesth 62:203-218.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Jamjoom BA, Jamjoom AB (2014) Efficacy of intraoperative epidural steroids in lumbar discectomy: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:146.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Rathmell JP, Benzon HT, Dreyfuss P, Huntoon M, Wallace M, et al. (2015) Safeguards to prevent neurologic complications after epidural steroid injections: consensus opinions from a multidisciplinary working group and national organizations. Anesthesiology 122:974-984.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Donnally CJ, Rush AJ, Rivera S, Vakharia RM, Vakharia AM, et al. (2018) An epidural steroid injection in the 6 months preceding a lumbar decompression without fusion predisposes patients to post-operative infections. J Spine Surg 4:529-533.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kreitz TM, Mangan J, Schroeder GD, Kepler CK, Kurd MF, et al. (2021) Do preoperative epidural steroid injections increase the risk of infection after lumbar spine surgery? Spine 46:E197-E202.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Seavey JG, Balazs GC, Steelman T, Helgeson M, Gwinn DE, et al. (2017) The effect of preoperative lumbar epidural corticosteroid injection on postoperative infection rate in patients undergoing single-level lumbar decompression. Spine J 17:1209-1214.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Li P, Hou X, Gao L, Zheng X (2020) Infection risk of lumbar epidural injection in the operating theatre prior to lumbar fusion surgery. J Pain Res 13:2181-2186.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Pisano AJ, Seavey JG, Steelman TJ, Fredericks DR, Helgeson MD, et al. (2020) The effect of lumbar corticosteroid injections on postoperative infection in lumbar arthrodesis surgery. J Clin Neurosci 71:66-69.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Singla A, Yang S, Werner BC, Cancienne JM, Nourbakhsh A, et al. (2017) The impact of preoperative epidural injections on postoperative infection in lumbar fusion surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 26:645-649.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Hartveldt S, Janssen SJ, Wood KB, Cha TD, Schwab JH, et al. (2016) Is there an association of epidural corticosteroid injection with postoperative surgical site infection after surgery for lumbar degenerative spine disease? Spine 41:1542-1547.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Koltsov JCB, Smuck MW, Alamin TF, Wood KB, Cheng I, et al. (2021) Preoperative epidural steroid injections are not associated with increased rates of infection and dural tear in lumbar spine surgery. Eur Spine J 30:870-877.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Coutinho AE, Chapman KE (2011) The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol 335:2-13.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Shakya A, Sharma A, Singh V, Rathore A, Garje V, et al. (2022) Preoperative lumbar epidural steroid injection increases the risk of a dural tear during minimally invasive lumbar discectomy. Int J Spine Surg 16:505-511.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Epstein NE (2014) Commentary: Unnecessary preoperative epidural steroid injections lead to cerebrospinal fluid leaks confirmed during spinal stenosis surgery. Surg Neurol Int 5:S325-S328.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kazarian GS, Steinhaus ME, Kim HJ (2022) The impact of corticosteroid injection timing on infection rates following spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Spine J 12:1524-1534.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Slucky AV, Sacks MS, Pallares VS, Malinin TI, Eismont FJ (1999) Effects of epidural steroids on lumbar dura material properties. Journal of spinal disorders 12:331-340.

[Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Karnani DN, Dirain CO, Antonelli PJ (2020) The effects of steroids on survival of mouse and human tympanic membrane fibroblasts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 163:382-388.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Labaran LA, Puvanesarajah V, Rao SS, Chen D, Shen FH, et al. (2019) Recent preoperative lumbar epidural steroid injection is an independent risk factor for incidental durotomy during lumbar discectomy. Global spine J 9:807-812.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Dong RP, Zhang Q, Yang LL, Cheng XL, Zhao JW (2023) Clinical management of dural defects: A review. World J Clin Cases 11:2903-2915.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang S, Kim W, Kong HH, Do KH, Choi KH (2020) Epidural steroid injection versus conservative treatment for patients with lumbosacral radicular pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 99:e21283.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Nandi J, Chowdhery A (2017) A randomized controlled clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of caudal epidural steroid injection in lumbosacral sciatica. J Clin Diagn Res 11:RC04-RC08.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Kent ML, Hurley RW, Oderda GM, Gordon DB, Sun E, et al. (2019) American society for enhanced recovery and perioperative quality initiative-4 joint consensus statement on persistent postoperative opioid use: definition, incidence, risk factors, and health care system initiatives. Anesth Analg 129:543-552.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Yoo KH, Sadeghzadeh S, Shah A,

Veeravagu A (2023) Timing of Lumbar ESIs:

Do Pre-operative Epidural Injections Effect

Lumbar Spine Surgery Outcomes. J Neurol Neurosci Vol. 1

5 No.S9:001